Published online Dec 5, 2025. doi: 10.4331/wjbc.v16.i4.112221

Revised: August 3, 2025

Accepted: October 21, 2025

Published online: December 5, 2025

Processing time: 136 Days and 10.6 Hours

Chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity is a significant complication in cancer therapy, limiting treatment efficacy and worsening patient outcomes. Recent studies have implicated the gut microbiome and its key metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), in mediating inflammation, oxidative stress, and cardiac damage. The gut-heart axis is incre

To systematically review existing evidence on the role of gut microbiome alter

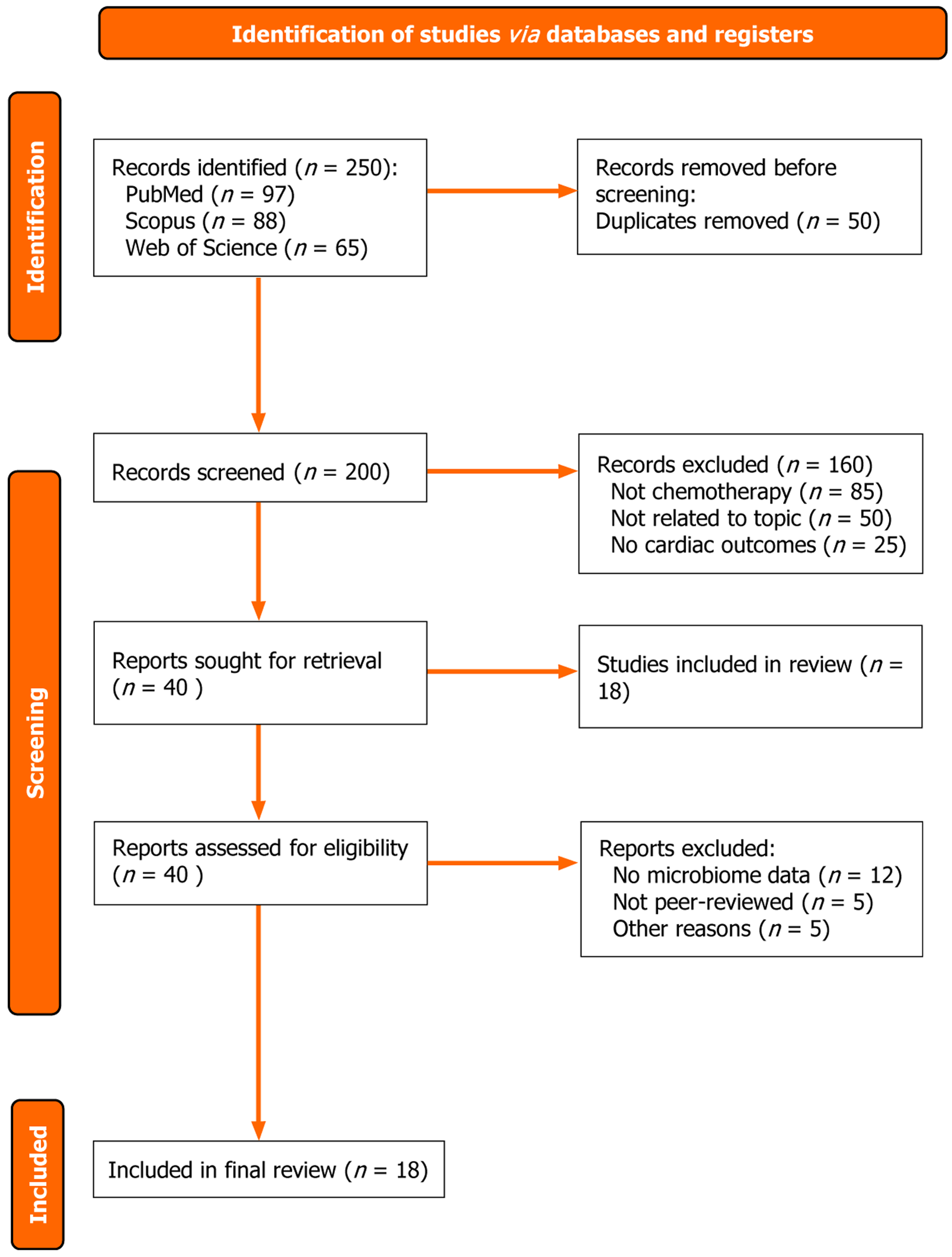

A systematic literature search was conducted in PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science for studies published between January 2013 and December 2024. Studies were included if they examined chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity in relation to gut microbiota composition, microbial metabolites (e.g., SCFAs, TMAO), or microbiome-targeted interventions. Selection followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. Data extraction focused on microbiota alterations, mechanistic pathways, cardiac outcomes, and quality assessments using standardized risk-of-bias tools.

Eighteen studies met the inclusion criteria. Chemotherapy was consistently associated with gut dysbiosis characterized by reduced SCFA-producing bacteria and increased TMAO-producing strains. This imbalance contributed to gut barrier disruption, systemic inflammation, and oxidative stress, all of which promote myocardial damage. SCFA depletion weakened anti-inflammatory responses, while elevated TMAO levels exacerbated cardiac fibrosis and dysfunction. Preclinical studies showed promising cardioprotective effects from probiotics, prebiotics, dietary interventions, and fecal microbiota transplantation, though human data remain limited.

Gut microbiome dysregulation plays a crucial role in the development of chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity. Altered microbial composition and metabolite production trigger systemic inflammation and cardiac injury. Microbiome-targeted therapies represent a promising preventive and therapeutic approach in cardio-oncology, warranting further clinical validation through well-designed trials.

Core Tip: This systematic review highlights the emerging role of the gut microbiome in chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity, focusing on how dysbiosis disrupts microbial metabolite balance, particularly short-chain fatty acids and trimethylamine-N-oxide, to drive inflammation, oxidative stress, and cardiac damage. The review synthesizes mechanistic insights and evaluates microbiome-targeted interventions such as probiotics, prebiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation. It emphasizes the gut-heart axis as a novel therapeutic target in cardio-oncology and underscores the need for standardized clinical trials to translate these findings into personalized medicine.

- Citation: Abdulaal R, Afara I, Harajli A, Al Mashtoub E, Tarchichi A, Hassan K, Afara A, Abou Fakher J, Salhab S, Fassih I, Tlais M. Gut microbiome and chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity: A systematic review of evidence and emerging therapies. World J Biol Chem 2025; 16(4): 112221

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8454/full/v16/i4/112221.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4331/wjbc.v16.i4.112221

Cancer remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, as it is a global public health issue with an alarming increase in incidence. According to the latest GLOBOCAN 2024 estimates, approximately 20.9 million new cancer cases and 10.4 million cancer-related deaths are expected globally in 2024, reinforcing cancer’s position as a major global health concern[1]. The gut microbiome refers to the diverse community of microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, and fungi, that reside in the human gastrointestinal tract. These microbes play essential roles in metabolism, immunity, and systemic health, including modulating inflammation and oxidative stress. Some of the most effective therapies used to treat cancer are chemotherapy agents, such as anthracyclines, which significantly improve cancer survival rates. Among chemotherapeutic agents, anthracyclines such as doxorubicin are widely used due to their efficacy against a range of malignancies. Doxorubicin acts by intercalating into DNA and inhibiting topoisomerase II, but its use is often limited by dose-dependent cardiotoxicity, which can manifest years after treatment. However, these benefits often accompany feared side effects that limit the treatment’s efficacy, one of them being chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity (CIC). In a previous meta-analysis, 22815 cancer patients were followed for 9 years, and 17.9% of these patients developed early signs of cardiotoxicity, 6.3% developed clinically apparent cardiotoxicity, and 10.6% developed overall cardiova

The gut microbiome has emerged as a potential factor that can exacerbate CIC through the gut-heart axis relationship. The gut microbiota regulates systemic health, often influencing various processes, such as inflammation and metabolic pathways[6]. The relationship between the heart and gut has been increasingly recognized, as recent studies have found that the gut is a key player in cardiovascular diseases[6]. Gut microbiome imbalance, or dysbiosis, can lead to processes such as systemic inflammation or oxidative stress, both of which mirror CIC pathophysiology[7]. For instance, a recent study by Huang et al explored the role of gut microbiota in CIC, specifically doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. They found that doxorubicin administration induced gut dysbiosis, including a decrease in Allobaculum and Muribaculum bacterial species and an increase in Faecalibaculum and Duboisella bacterial species[7]. The study also tested whether these gut microbiota imbalances directly correlated to cardiovascular disease by depleting gut microbiota with antibiotics and testing whether similar results occurred[7]. Antibiotic depletion of gut microbiota led to doxorubicin-induced myocardial damage and cardiomyocyte apoptosis[7]. Another study by Shariff et al[6] discussed how dietary patterns, which shape the composition of the gut microbiota, can affect cardiovascular health. Interventional therapies such as probiotics, prebiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation, which improve gut microbiota imbalances, can reduce cardiovascular risk[6]. Therefore, such therapies have a protective role against certain cardiovascular diseases such as coronary artery disease because they mitigate inflammatory pathways and reduce oxidative stress[6].

This systematic review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to ensure transparency and methodological rigor. A comprehensive search of PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science was performed to identify studies published between January 2013 and December 2024. The search focused on the role of the gut microbiome in chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity, particularly exploring microbial dysbiosis, gut-derived metabolites, and potential therapeutic interventions. The search strategy utilized combinations of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and keywords, such as "gut microbiome", "intestinal microbiota", "chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity", "gut-heart axis", "short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)", "TMAO", "probiotics", "prebiotics", and "fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT)". Table 1 summarizes the search strategy, which was refined iteratively to ensure comprehensive coverage of relevant primary research, systematic reviews, and preclinical studies. The date range (January 2013 to December 2024) was chosen to reflect the most contemporary understanding of gut microbiome research, which has seen significant methodological and conceptual advancements in the past decade. Earlier studies often lacked advanced sequencing technologies and consistent definitions of microbiome-related terms, limiting their comparability and relevance to current practices (Table 1).

| Database | Date range | Search terms (MeSH + keywords + Boolean) | Limits applied |

| PubMed | January 2013 – December 2024 | ("gut microbiome"[MeSH] OR "intestinal microbiota" OR "gut bacteria") AND ("cardiotoxicity"[MeSH] OR "cardiac toxicity") AND ("chemotherapy"[MeSH] OR "doxorubicin" OR "anthracyclines") AND ("SCFAs" OR "TMAO" OR "gut-heart axis") | English language; human and animal studies; peer-reviewed only |

| Scopus | January 2013 – December 2024 | TITLE-ABS-KEY (("gut microbiome" OR "intestinal microbiota") AND ("cardiotoxicity" OR "cardiac toxicity") AND ("chemotherapy" OR "doxorubicin" OR "anthracyclines") AND ("SCFAs" OR "TMAO" OR "gut-heart axis")) | English language; peer-reviewed; exclude conference papers |

| Web of Science | January 2013 – December 2024 | TS = ("gut microbiome" OR "intestinal microbiota") AND TS = ("cardiotoxicity" OR "cardiac toxicity") AND TS = ("chemotherapy" OR "anthracyclines") AND TS=("SCFAs" OR "TMAO") | English language; document types: Article, Review |

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Examined chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity in relation to the gut microbiome; (2) Investigated mechanisms such as microbial dysbiosis, systemic inflammation, microbial translocation, or oxidative stress; (3) Evaluated microbial metabolites such as SCFAs or trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) and their association with cardiac outcomes; or (4) Assessed microbiome-targeted interventions, including probiotics, prebiotics, dietary changes, or FMT. Eligible study types included human clinical studies, preclinical animal experiments, and systematic reviews. Articles were excluded if they: (1) Focused on cardiotoxicity unrelated to chemotherapy; (2) Lacked microbiome analysis or relevant mechanistic data; (3) Were case reports, conference abstracts, or non-peer-reviewed; or (4) Were not available in English.

The initial database search identified 250 articles. After removing 50 duplicates, titles and abstracts of 200 studies were screened by four independent reviewers. A total of 160 studies were excluded due to irrelevance, leaving 40 articles for full-text review. Following a thorough review of full texts, 22 studies were excluded for not meeting inclusion criteria. During full-text screening, five articles were excluded because they were published in non-peer-reviewed sources such as preprint servers (e.g., medRxiv or bioRxiv) or conference proceedings without formal journal publication. Another five studies were excluded for other specific reasons: Two lacked original data despite appearing as reviews, one duplicated already included data, one focused solely on cardiotoxicity without reference to microbiome mechanisms, and one article was retracted due to methodological concerns. This resulted in 18 articles included in the final synthesis. Discrepancies in study selection were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer.

Data extraction was conducted using a standardized form to ensure consistency. Extracted data included study characteristics (e.g., type, population, and sample size), chemotherapy regimens, microbiome analysis methods (e.g., 16S rRNA sequencing, metagenomics), microbial taxa, metabolites (e.g., SCFAs and TMAO), and cardiac outcomes. For preclinical studies, additional details were collected on experimental design and microbiome-targeted interventions, such as probiotics or FMT.

The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed using standardized tools appropriate to each study type. Preclinical animal studies were evaluated using the ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) guidelines, with most demonstrating low to moderate risk of bias based on reporting of randomization, blinding, and experimental rigor. Observational human studies were assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, generally showing low risk of bias across domains of selection, comparability, and outcome assessment. Review articles were excluded from formal quality grading. Overall, most preclinical studies maintained good methodological standards, while human studies demonstrated adequate risk-of-bias profiles to support the reliability of their findings. Studies that failed to meet minimum quality standards were excluded during the full-text review.

The findings of the included studies were synthesized narratively, organized into four thematic areas: (1) Gut microbiome profiles and cardiotoxicity; (2) Microbial metabolites and cardiotoxicity; (3) Mechanistic pathways; and (4) Microbiome-targeted interventions. A PRISMA flow diagram summarizing the study selection process is presented below (Figure 1).

Dysbiosis or disruption of the gut microbiota has emerged as a critical factor in exacerbating chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity. Studies have shown that chemotherapy, particularly doxorubicin, can alter the gut microbiome by depleting beneficial bacteria and promoting overgrowth of pathogenic taxa. This disruption weakens the intestinal barrier, allowing pro-inflammatory bacterial components to enter the circulation, exacerbating myocardial damage[8,9]. Resulting systemic inflammation further aggravates myocardial injury by triggering inflammatory cytokine pathways. Animal and human studies have consistently reported increased levels of inflammatory markers and oxidative stress in individuals with chemotherapy-induced dysbiosis. Hu et al[10] investigated the cardioprotective effects of emodin, a natural anthraquinone compound derived from traditional Chinese herbs such as Rheum palmatum (rhubarb), known for its anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and microbiota-modulating properties, which restored gut microbial balance and alleviated doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Similarly, Fan et al[9] found that rats exposed to doxorubicin with severe dysbiosis presented with greater cardiac lesions, emphasizing the relationship between gut dysbiosis and cardiotoxicity severity.

The role of dysbiosis in exacerbating adverse cardiac outcomes remains an area of ongoing research. Ciernikova et al[8] emphasized immune modulation as a key mechanism, where dysbiosis suppresses regulatory T-cell activity and enhances pro-inflammatory immune responses. In contrast, Morel et al[11] identified oxidative stress as a major con

The association between specific bacterial taxa and cardiotoxicity suggests a complex gut-heart axis. Protective bacteria, such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, are often depleted during chemotherapy, whereas harmful bacteria proliferate under dysbiotic conditions. These species are known for their anti-inflammatory effects, ability to maintain the gut barrier, and immune modulation. For example, Kunika et al[13] demonstrated that Lactobacillus supplementation in rats treated with cisplatin leads to reduced cardiac inflammation and improved cardiac function. Additionally, Ciernikova et al[8] explored the potential role of Akkermansia muciniphila in cardioprotection, as it promotes gut barrier integrity and reduces systemic inflammation. They also reported that depletion of beneficial taxa during chemotherapy, including Faecalibacterium and Ruminococcus, is associated with greater cardiac damage. These genera produce SCFAs, which are important for gut barrier function and inflammation reduction. Furthermore, dysbiosis in chemotherapy often involves the overgrowth of pathogenic taxa, such as Proteobacteria, which is linked to inflammation and oxidative stress, contributing to cardiac damage[9]. Liu et al[14] reported an increase in Helicobacteraceae and Coriobacteriaceae DOX-induced gut microbiota dysbiosis. Studies have also reported the growth of Clostridium species under dysbiotic conditions, which is associated with inflammatory signaling and poor cardiac outcomes[8]. Kunika et al[13] provided similar findings in humans, underlining the clinical relevance of these microbial shifts.

An inverse relationship between protective and harmful taxa has consistently been observed across studies. When beneficial bacteria such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus are diminished, pathogenic taxa dominate, initiating a cycle of inflammation and oxidative damage that exacerbates cardiotoxicity. This highlights the importance of microbial balance in preventing chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity. Additionally, differences in microbial diversity between patients who develop cardiotoxicity and those who do not emphasize the importance of microbial diversity in cardiac health. Huang et al[7] observed reduced alpha diversity in rats treated with doxorubicin, which correlated with the loss of beneficial bacterial populations and an increase in pathogenic taxa. Similarly, Fan et al[9] found that lower microbial diversity is strongly associated with cardiac damage, as determined by histological markers and echocardiographic parameters. Nguyen also reported that breast cancer patients who developed cardiotoxicity had significantly lower microbial diversity compared to those who did not[12]. Ciernikova et al[8] focused on the compositional changes during dysbiosis, noting an increase in the abundance of pathogenic taxa, such as Proteobacteria, in patients with cardiotoxicity. This shift was inversely correlated with microbial diversity, underscoring the link between microbial composition and diversity in the context of cardiotoxicity.

Harmful bacterial taxa, particularly members of Clostridium, Proteobacteria, and Helicobacteraceae, contribute to cardiotoxicity via several mechanisms. These include the overproduction of lipopolysaccharides (LPS), which stimulate systemic inflammation through toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signaling, and the generation of pro-oxidant metabolites that damage cardiac tissue. Additionally, these taxa often disrupt intestinal tight junctions, promoting microbial translocation and further exacerbating myocardial injury. For example, the proliferation of Coriobacteriaceae is associated with increased trimethylamine (TMA) production, a precursor of the cardiotoxic metabolite TMAO[8,9]. Several studies reported the proliferation of Escherichia coli, a gram-negative bacterium whose lipopolysaccharide-rich outer membrane strongly activates pro-inflammatory pathways via TLR4, contributing to gut barrier dysfunction and systemic inflammation[7-9].

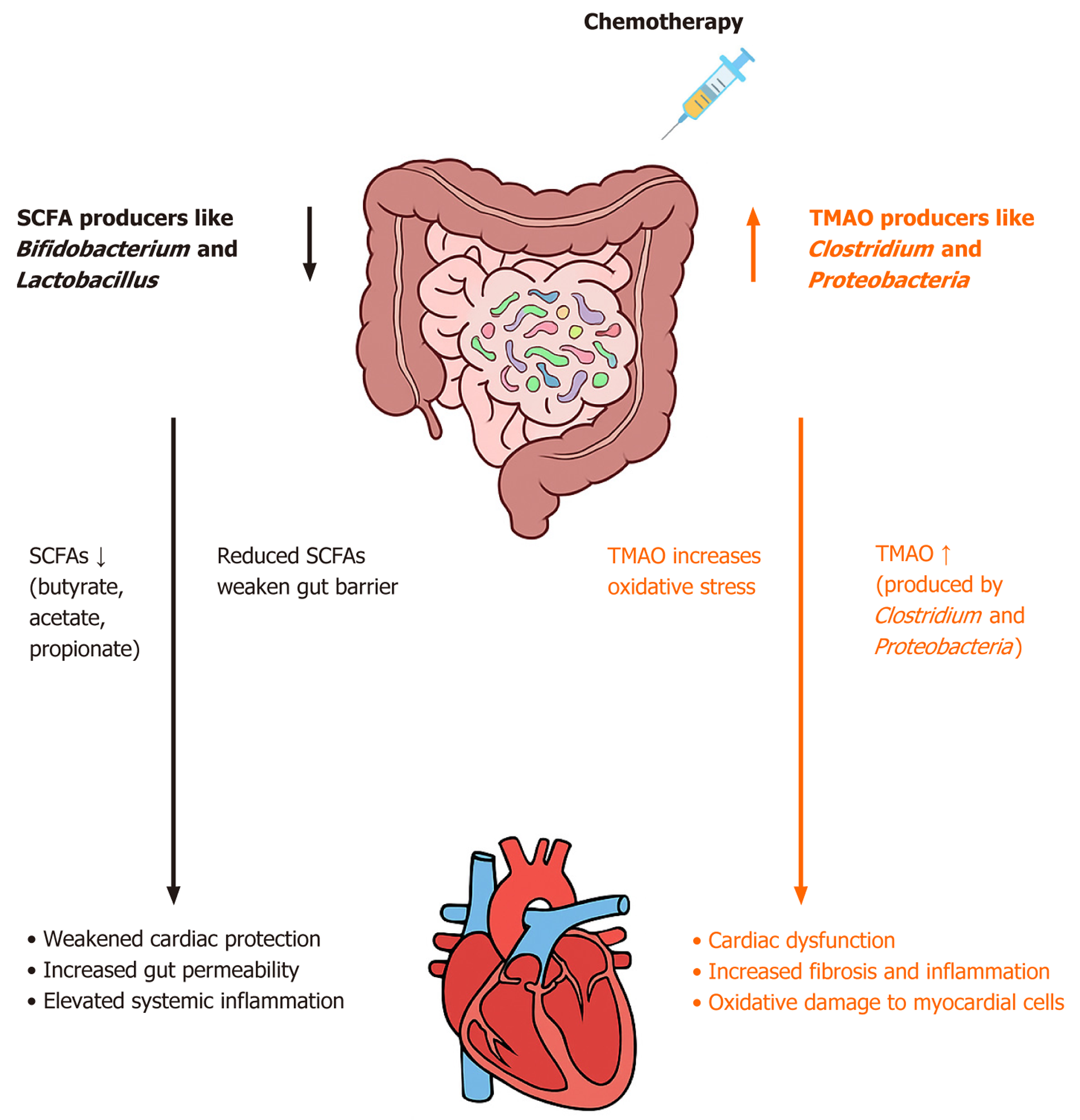

Gut microbial metabolites such as SCFAs and TMAO play pivotal roles in chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity. Acting as vital links in the gut-heart axis, these metabolites influence systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, and heart injury. SCFAs, including butyrate, acetate, and propionate, are produced when the gut microbiota ferments dietary fiber. Among these, butyrate has received significant attention owing to its heart-protective properties. Ciernikova et al[8] emphasized butyrate’s importance in maintaining the intestinal barrier and reducing systemic inflammation. They found that chemotherapy disrupts butyrate-producing bacteria such as Faecalibacterium and Ruminococcus, leading to decreased SCFA levels. This disruption weakens the gut barrier, allowing harmful bacterial components to leak into circulation and trigger cardiac injury. Similarly, Huang et al[7] demonstrated that restoring butyrate levels in animal models reduces cardiac inflammation and oxidative stress, leading to better heart function. Fan et al[9] also explained the protective effects of SCFAs, showing that animals with sustained butyrate production had lower levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines like interleukin (IL)-6 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), along with fewer oxidative stress markers. Similarly, Xu et al[15] further emphasized the immunomodulatory properties of SCFAs, particularly their ability to inhibit pro-inflammatory signaling pathways, such as the nuclear factor-kappa B pathway, and protect mitochondrial function within cardiac cells, thereby reducing oxidative damage.

TMAO, a pro-inflammatory metabolite produced by gut microbial metabolism of dietary choline, carnitine, and phosphatidylcholine, has been strongly linked to worsening cardiac injury during chemotherapy. Kunika et al[13] identified elevated TMAO levels as a key factor in chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity, given that chemotherapy-related gut dysbiosis increases TMA-producing bacteria like Clostridium and Lactonifactor. Increased TMAO levels are associated with increased systemic inflammation and oxidative stress in the heart, leading to structural and functional cardiac abnormalities. Ciernikova et al[8] expanded these findings, showing that TMAO amplifies inflammatory cytokine production, further damaging heart cells. Supporting this, Huang et al[7] demonstrated that high TMAO levels in doxorubicin-treated rats are linked to increased cardiac fibrosis and impaired left ventricular function. These results demonstrated the harmful role of TMAO in heart disease, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target.

SCFAs and TMAO play opposing roles in the gut-heart axis, with SCFAs offering protective benefits and TMAO causing harm (Figure 2). The balance between these metabolites depends on gut microbiota composition and func

Interventions targeting the gut microbiome, including probiotics, prebiotics, dietary modifications, and FMT, have shown potential in mitigating chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity. These strategies aim to restore microbial balance, enhance the production of protective metabolites such as SCFAs, and reduce systemic inflammation, which may help alleviate cardiac injury.

Probiotics are live microorganisms that confer health benefits when administered in sufficient amounts. Several studies have investigated their roles in modulating gut dysbiosis and reducing inflammation associated with chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity. Probiotic strains, such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, improve gut microbial composition and reduce inflammation markers, such as IL-6 and C-reactive protein, in conditions such as chronic kidney disease and doxorubicin-induced damage[16,17]. Similarly, Sutedja et al[18] stressed the role of inflammation-driven damage in CIC and noted that probiotic modulation of the gut microbiome could potentially mitigate such inflammation. Zhao et al[17] found that probiotic interventions in animal models promoted the growth of beneficial taxa such as Lactobacillus, Bacteroides, and Akkermansia muciniphila, which led to enhanced SCFA production and reduced TMAO levels. Chen et al[19] demonstrated that Prevotellaceae produces butyrate, which alleviates PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor-induced cardiotoxicity via the PPARα-CYP4X1 axis in colonic macrophages. As such, butyrate supplementation could have a protective role in PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor-related cardiotoxicity. Together, these studies support the role of microbiome modulation in reducing inflammation and improving cardiac outcomes, although further studies are required to evaluate the broader clinical applicability of probiotics in cardiotoxicity.

Prebiotics are non-digestible substances that promote the growth of beneficial microorganisms in the gut. Prebiotics such as inulin and resistant starch promote the growth of SCFA-producing bacteria, such as Faecalibacterium and Roseburia, which help mitigate systemic inflammation and oxidative stress, contributing to improved cardiac outcomes[16]. Zhao et al[17] reported that prebiotic supplementation in atherosclerosis models increased SCFA levels and decreased pro-inflammatory metabolites, which may reduce cardiovascular risk. Huang et al[7] discussed the potential of prebiotics in mitigating doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by promoting gut-derived metabolites like butyrate, which can help protect cardiac function. Further well-controlled clinical trials are needed to evaluate the efficacy of probiotics and prebiotics in CIC, as their effectiveness remains unclear.

Dietary modifications, particularly plant-based and low-protein diets, aim to modulate gut microbiota by promoting beneficial bacterial populations and reducing proteolytic fermentation associated with inflammation. Zhao et al[17] discussed the impact of polyphenols and plant-based sterols in promoting beneficial microbiota, such as Bacteroides and Akkermansia muciniphila, which may contribute to gut barrier integrity and systemic inflammation reduction. Ciernikova et al[8] also discussed the role of the microbiome in modulating the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cancer therapies, which may influence treatment efficacy and side effects, including chemotherapy. Although specific studies addressing dietary interventions for CIC are limited, the role of fiber-rich diets and polyphenolic compounds suggests possible benefits in improving gut health and reducing inflammatory responses.

FMT, the transplantation of fecal material from healthy donors, could be promising in restoring gut microbial balance. An et al[20] demonstrated that FMT improved cardiac function and reduced gut damage in doxorubicin-treated mice, promoting microbial diversity and increasing the abundance of SCFA-producing taxa, such as Prevotellaceae and Rikenellaceae. These changes are associated with reduced cardiac fibrosis and inflammation, but their clinical application remains limited due to safety concerns, donor variability, and lack of standardized protocols. Zhao et al[17] emphasized that well-controlled clinical studies are needed to evaluate the long-term effects of FMT on the gut microbiota and cardiovascular health.

The feasibility and effectiveness of microbiota-targeted interventions depend on a variety of factors including patient characteristics, treatment duration, and microbiota-host interactions. While preclinical studies have consistently demonstrated that FMT improves gut and cardiac health by restoring microbial balance and reducing inflammation, evidence for probiotics and prebiotics varies. Krukowski et al[16] and Zhao et al[17] found that although probiotics and prebiotics are generally safe and well-tolerated, their efficacy in reducing inflammation and uremic toxins remains inconsistent. Large-scale randomized controlled trials are needed to better evaluate the clinical utility of microbiota-targeted interventions, particularly for cardiotoxicity prevention and management.

Chemotherapy-induced gut dysbiosis contributes to cardiotoxicity through mechanisms such as microbial translocation, immune modulation, oxidative stress, and intestinal barrier disruption. Microbial translocation, driven by gut barrier disruption during chemotherapy, emerges as a critical contributor to systemic inflammation and cardiac injury. Zhou et al[21] demonstrated that translocated bacterial components, particularly LPS, activate TLR4, inducing inflammatory cytokine release, such as IL-6 and TNF-α. This pathway exacerbates inflammation and worsens cardiac outcomes post-myocardial infarction. Similarly, Li et al[22] reported that doxorubicin-treated mice with impaired gut barriers exhibited elevated circulating endotoxin levels, amplifying inflammation and cardiac dysfunction. Tight junction proteins such as zonula occludens-1 and Occludin are crucial for maintaining intestinal integrity[21,22]. While Zhou et al[21] primarily focused on the implications of microbial translocation in myocardial infarction, Li et al[22] provided evidence specific to CIC, discussing therapeutic interventions that restore the gut barrier to mitigate systemic and cardiac inflammation. Zhou et al[21] emphasized the potential of targeting TLR4-mediated inflammatory pathways, while Li et al[22] demonstrated the efficacy of a nanodrug in restoring tight junction proteins and reducing microbial translocation.

Gut dysbiosis and immune dysregulation could be a critical pathway linking gut microbiota to cardiotoxicity. Ciernikova et al[8] described how chemotherapy-induced dysbiosis suppresses regulatory T-cell activity and enhances pro-inflammatory immune responses, amplifying systemic inflammation. Complementing this, Jia et al[23] demonstrated the role of SCFAs in maintaining immune homeostasis. The reduction of SCFA-producing bacteria, such as Faecalibacterium and Roseburia, due to dysbiosis impairs immune regulation and perpetuates inflammatory responses. Meng et al[24] reinforced these findings, focusing on gut-derived metabolites that directly influence inflammatory pathways. While all three studies converged on the importance of immune modulation, Jia et al[23] uniquely discussed the role of SCFAs, contrasting with the broader immune-focused discussions in Ciernikova et al[8] and Meng et al[24].

Chemotherapy directly damages the intestinal mucosa, thereby increasing permeability and systemic inflammation. Yixia et al[25] documented significant destruction of intestinal epithelial cells, including the loss of tight junction proteins during chemotherapy, which facilitates microbial translocation. Li et al[22] corroborated these findings, demonstrating that therapeutic restoration of gut barrier integrity, such as through a bacterial membrane protein nanodrug, reduces systemic inflammation and improves cardiac outcomes in doxorubicin-treated models. While both studies emphasize gut barrier disruption, Li et al[22] further present a potential intervention, providing a complementary perspective on miti

The depletion of SCFAs, a hallmark of gut dysbiosis, exacerbates oxidative stress and CIC. Jia et al[23] showed that SCFAs such as butyrate protect the gut barrier, regulate immune responses, and reduce oxidative stress. The reduction of SCFA-producing bacteria during dysbiosis weakens these protective mechanisms, leading to systemic inflammation and increased cardiac injury. Meng et al[24] further developed the link between SCFA depletion and increased oxidative stress, showing that reduced SCFA levels in animal models correlate with worsened cardiac outcomes. Both studies converge on the centrality of SCFAs but differ in their focus; Jia et al[23] emphasize gut barrier and immune regulation, while Meng et al[24] primarily examine oxidative stress.

Our findings have shed light on the importance of the gut microbiome in both the pathogenesis and prevention of CIC. This has led to novel approaches to risk assessment and prevention in the field of cardio-oncology. Dysbiosis, which is characterized by the depletion of beneficial taxa such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus and the overgrowth of pathogenic species such as Escherichia coli and Clostridium, weakens the intestinal barrier and triggers systemic inflammation, which potentially leads to cardiotoxicity. We have highlighted several mechanistic pathways that play a role in the complex gut-heart axis and the amplification of myocardial damage. These included microbial translocation, immune dysregulation, and oxidative stress.

Our study emphasizes two main microbial metabolites that play opposite roles, highlighting the dualistic nature of the gut microbiome in the context of cardiotoxicity. On one hand, SCFAs such as butyrate have recently emerged as protective agents, preserving gut barrier integrity and decreasing systemic inflammation. On the other hand, dysbiosis has been shown to cause elevated levels of TMAO, activating inflammatory and oxidative pathways, further exacerbating cardiac damage. This highlights the potential of microbial balance as a therapeutic target to reduce CIC, allowing cli

Gut microbiome research, particularly in relation to cardiotoxicity, fails to explore individual variability in microbial composition, which is influenced by genetics, diet, and health status. This greatly affects the clinical translation of the current literature, especially considering the goal of standardizing findings across diverse populations. One example of this limitation is that the abundance and functional capacity of cardioprotective taxa, such as Faecalibacterium and Ruminococcus, vary widely in the population thus preventing the general application of these findings.

Additionally, current studies rarely account for host–microbiome interactions, which are shaped by complex factors including host immune responses, epigenetics, and metabolic status. These interactions can significantly influence the microbiome’s role in drug metabolism, inflammatory signaling, and cardiovascular outcomes. Furthermore, the translational relevance of preclinical models is limited by interspecies differences in gut microbiota composition, immune function, and chemotherapy pharmacokinetics. While animal models provide mechanistic insights, their microbial ecosystems differ substantially from humans, complicating extrapolation to clinical settings. Addressing these gaps requires integrating multi-omics approaches, patient-specific microbiome profiling, and more humanized microbiota models to improve translational fidelity.

Previous work failed to provide standardization of sample collection, sequencing techniques, and data interpretation. Variability in this domain prevents data reproducibility and cross study comparisons. Current literature also fails to bridge preclinical insights and clinical practice. While animal models have shown interventions such probiotics and SCFA supplementation to be efficacious in improving gut dysbiosis and CIC, clinical studies have been limited by small sample sizes and inconsistent outcomes. Hence, there is an urgent need for more randomized clinical trials. The complexity of the gut-heart axis and its relation to chemotherapy poses a great challenge in research. As a solution to this problem, longitudinal studies can be used to provide more insight into the temporal interplay between microbiota changes and its cardiac effects.

Baseline quantification and qualification of microbial diversity and metabolite levels as biomarkers allows personal interventions to prevent and possibly reverse CIC. As such, microbiome profiling could play a huge role in utilizing the therapeutic potential of microbiome interventions.

Promising microbiome-targeted interventions and alterations included probiotic and prebiotic supplementation to enhance beneficial SCFA production, FMT to restore microbial diversity, and dietary modifications to promote beneficial taxa growth. We recommend that these interventions be further studied and explored through larger multicenter clinical trials, as they not only reduce inflammation and oxidative stress but also improve chemotherapy tolerance and outcomes.

Taken together, these findings highlight the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration between oncologists, cardiologists, and microbiologists. This collaboration potentially standardizes microbiome-based interventions, allowing for the integration of the current literature into clinical practice.

This systematic review highlights the significant role of the gut microbiome in CIC, revealing its potential as both a marker of risk and a therapeutic target. Dysbiosis contributes to cardiotoxicity through mechanisms such as systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, and microbial translocation, while gut-derived metabolites like SCFAs and TMAO demonstrate opposing effects on cardiac health. Emerging interventions, including probiotics, prebiotics, dietary modifications, and FMT, show promise in preclinical studies but require validation in robust clinical trials. Future research should focus on standardizing microbiome analysis methods and conducting longitudinal studies to evaluate the safety and efficacy of microbiome-targeted therapies. Integrating microbiome profiling into clinical care could improve risk stratification and enable personalized treatment strategies in cardio-oncology. The gut-heart axis represents a promising avenue to mitigate the cardiovascular burden of cancer therapy, offering new possibilities for improving patient out

| 1. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 68589] [Article Influence: 13717.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (201)] |

| 2. | Lotrionte M, Biondi-Zoccai G, Abbate A, Lanzetta G, D'Ascenzo F, Malavasi V, Peruzzi M, Frati G, Palazzoni G. Review and meta-analysis of incidence and clinical predictors of anthracycline cardiotoxicity. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112:1980-1984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 274] [Cited by in RCA: 276] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Florescu M, Cinteza M, Vinereanu D. Chemotherapy-induced Cardiotoxicity. Maedica (Bucur). 2013;8:59-67. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Dempke WCM, Zielinski R, Winkler C, Silberman S, Reuther S, Priebe W. Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity - are we about to clear this hurdle? Eur J Cancer. 2023;185:94-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Angsutararux P, Luanpitpong S, Issaragrisil S. Chemotherapy-Induced Cardiotoxicity: Overview of the Roles of Oxidative Stress. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2015;2015:795602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Shariff S, Kwan Su Huey A, Parag Soni N, Yahia A, Hammoud D, Nazir A, Uwishema O, Wojtara M. Unlocking the gut-heart axis: exploring the role of gut microbiota in cardiovascular health and disease. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2024;86:2752-2758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Huang J, Wei S, Jiang C, Xiao Z, Liu J, Peng W, Zhang B, Li W. Involvement of Abnormal Gut Microbiota Composition and Function in Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:808837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ciernikova S, Sevcikova A, Mladosievicova B, Mego M. Microbiome in Cancer Development and Treatment. Microorganisms. 2023;12:24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fan Y, Liang L, Tang X, Zhu J, Mu L, Wang M, Huang X, Gong S, Xu J, Liu T, Zhang T. Changes in the gut microbiota structure and function in rats with doxorubicin-induced heart failure. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023;13:1135428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hu S, Zhou J, Hao J, Zhong Z, Wu H, Zhang P, Yang J, Guo H, Chi J. Emodin ameliorates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by inhibiting ferroptosis through the remodeling of gut microbiota composition. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2024;326:C161-C176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Morel S, Delvin E, Marcil V, Levy E. Intestinal Dysbiosis and Development of Cardiometabolic Disorders in Childhood Cancer Survivors: A Critical Review. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2021;34:223-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nguyen SM, Pham AT, Nguyen LM, Cai H, Tran TV, Shu XO, Tran HTT. Chemotherapy-Induced Toxicities and Their Associations with Clinical and Non-Clinical Factors among Breast Cancer Patients in Vietnam. Curr Oncol. 2022;29:8269-8284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kunika, Frey N, Rangrez AY. Exploring the Involvement of Gut Microbiota in Cancer Therapy-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:7261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Liu X, Liu Y, Chen X, Wang C, Chen X, Liu W, Huang K, Chen H, Yang J. Multi-walled carbon nanotubes exacerbate doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by altering gut microbiota and pulmonary and colonic macrophage phenotype in mice. Toxicology. 2020;435:152410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Xu Y, Du H, Chen Y, Ma C, Zhang Q, Li H, Xie Z, Hong Y. Targeting the gut microbiota to alleviate chemotherapy-induced toxicity in cancer. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2024;50:564-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Krukowski H, Valkenburg S, Madella AM, Garssen J, van Bergenhenegouwen J, Overbeek SA, Huys GRB, Raes J, Glorieux G. Gut microbiome studies in CKD: opportunities, pitfalls and therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2023;19:87-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 25.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zhao X, Oduro PK, Tong W, Wang Y, Gao X, Wang Q. Therapeutic potential of natural products against atherosclerosis: Targeting on gut microbiota. Pharmacol Res. 2021;163:105362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sutedja JC, Tjandra DC, Oden GF, DE Liyis BG. Resveratrol as an adjuvant prebiotic therapy in the management of pulmonary thromboembolism. Minerva Cardiol Angiol. 2024;72:416-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chen Y, Liu Y, Wang Y, Chen X, Wang C, Chen X, Yuan X, Liu L, Yang J, Zhou X. Prevotellaceae produces butyrate to alleviate PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor-related cardiotoxicity via PPARα-CYP4X1 axis in colonic macrophages. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2022;41:1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 41.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | An L, Wuri J, Zheng Z, Li W, Yan T. Microbiota modulate Doxorubicin induced cardiotoxicity. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2021;166:105977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhou X, Li J, Guo J, Geng B, Ji W, Zhao Q, Li J, Liu X, Liu J, Guo Z, Cai W, Ma Y, Ren D, Miao J, Chen S, Zhang Z, Chen J, Zhong J, Liu W, Zou M, Li Y, Cai J. Gut-dependent microbial translocation induces inflammation and cardiovascular events after ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Microbiome. 2018;6:66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 29.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Li Z, Xing J, Ma X, Zhang W, Wang C, Wang Y, Qi X, Liu Y, Jian D, Cheng X, Zhu Y, Shi C, Guo Y, Zhao H, Jiang W, Tang H. An orally administered bacterial membrane protein nanodrug ameliorates doxorubicin cardiotoxicity through alleviating impaired intestinal barrier. Bioact Mater. 2024;37:517-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Jia Q, Li H, Zhou H, Zhang X, Zhang A, Xie Y, Li Y, Lv S, Zhang J. Role and Effective Therapeutic Target of Gut Microbiota in Heart Failure. Cardiovasc Ther. 2019;2019:5164298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Meng C, Wang X, Fan L, Fan Y, Yan Z, Wang Y, Li Y, Zhang J, Lv S. A new perspective in the prevention and treatment of antitumor therapy-related cardiotoxicity: Intestinal microecology. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;170:115588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Yixia Y, Sripetchwandee J, Chattipakorn N, Chattipakorn SC. The alterations of microbiota and pathological conditions in the gut of patients with colorectal cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Anaerobe. 2021;68:102361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/