Published online Jan 27, 2026. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.114227

Revised: October 22, 2025

Accepted: November 27, 2025

Published online: January 27, 2026

Processing time: 129 Days and 12.4 Hours

Although most acute pancreatitis (AP) cases are mild, up to 20% progress to severe disease, leading to substantial morbidity and mortality. Early risk stratification remains challenging because conventional scoring systems require multiple parameters and often depend on 24-48 hours of observation.

To evaluate whether serum phosphate levels measured upon hospital admission can predict disease severity and short-term clinical outcomes in patients with AP.

We retrospectively analyzed 1000 consecutive patients hospitalized for AP bet

SAP occurred in 60% of patients with hyperphosphatemia and in 20% of those with normophosphatemia (P < 0.001). Pancreatic necrosis (50% vs 10%) and ICU admission (70% vs 15%) were also significantly more frequent in the hyperphosphatemia group. Thirty-day mortality was 25% in the hyperphosphatemia group and 3% in the normophosphatemia group. Hyperphosphatemia independently predicted 30-day mortality (adjusted OR 5.8; 95%CI: 2.9-11.5; P < 0.001), and this association remained significant after adjustment for creatinine and AKI (adjusted OR 4.7; 95%CI: 2.1-10.3; P < 0.001).

Admission hyperphosphatemia independently predicts severe disease, pancreatic necrosis, ICU admission, and early mortality, highlighting a simple and inexpensive biomarker to support rapid risk stratification in AP.

Core Tip: Early risk stratification in acute pancreatitis remains a major clinical challenge, as conventional scoring systems require up to 48 hours and limit decision-making in the emergency setting. In this large 1000-patient cohort, admission hyperphosphatemia was strongly associated with severe disease, pancreatic necrosis, intensive care requirement, and 30-day mortality and was identified as an independent predictor of poor outcomes. These findings suggest that serum phosphate is an inexpensive, readily available biomarker that may complement existing tools and enable the prompt identification of high-risk patients at hospital admission.

- Citation: Özden Y, Buyukberber NM. Admission hyperphosphatemia as a predictor of severity and mortality in acute pancreatitis: A 1000-patient cohort study. World J Gastrointest Surg 2026; 18(1): 114227

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v18/i1/114227.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.114227

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a common, potentially life-threatening inflammatory disease of the pancreas. Gallstones and alcohol consumption are the most frequent etiological factors worldwide, although their relative distribution varies across regions[1]. In Turkey, a large multicenter study reported gallstones as the cause of 67% of AP cases, whereas alcohol accounted for only 4.2%[2]. Most cases are mild and self-limiting; however, 15%-20% progress to severe disease, leading to persistent organ failure and local complications. Mortality ranges from 3% to 10% overall but may reach 30%-50% in severe AP (SAP)[3].

Early prediction of severity is crucial for guiding intensive care management, optimizing fluid resuscitation, and preventing complications. Although several scoring systems (e.g., Ranson, BISAP, and APACHE II) have been developed, many require multiple parameters and up to 48 hours of observation, limiting their utility in emergency settings[3]. This limitation has prompted growing interest in rapidly measurable biochemical markers available at admission.

In this context, serum phosphate levels have emerged as a potential prognostic biomarker, supported by accumulating evidence that links phosphate disturbances to disease severity and mortality. Phosphate plays a key role in cellular energy metabolism and membrane integrity, and altered levels may reflect metabolic stress during tissue injury[4]. Recent studies have highlighted its prognostic relevance: A 2021 intensive care cohort identified serum phosphate as the strongest biochemical predictor of mortality in AP[5]; a 2006 case report first highlighted the occurrence of severe hypophosphatemia in gallstone pancreatitis[6]; and a 2021 retrospective analysis associated early hypophosphatemia with SAP, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and prolonged hospitalization[7].

These observations suggest that phosphate disturbances may have important prognostic implications in AP. Therefore, we investigated the association between serum phosphate levels at admission and key clinical outcomes, including disease severity, local complications, ICU admissions, and 30-day mortality, in a large patient cohort managed at a tertiary care hospital in Turkey. We hypothesized that hyperphosphatemia at admission would identify a distinct subgroup of AP patients at particularly high risk of adverse outcomes. Supporting this hypothesis, a recent large MIMIC-IV database analysis demonstrated that each 1 mg/dL increase in serum phosphate was associated with a 20%-25% higher hazard of in-hospital and 30-day mortality after adjustment for major confounders[8]. Building on these observations, our study aimed to validate this association in a broad, real-world, single-center cohort and to examine whether the prognostic value of phosphate persists after accounting for renal function and other clinically relevant factors.

This single-center cohort study was conducted retrospectively by reviewing the records of all eligible patients admitted with a diagnosis of AP between November 2023 and June 2025 at a tertiary care hospital in Turkey. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Acute-onset epigastric pain; (2) Serum amylase and/or lipase ≥ 3 × the upper limit of normal; and/or (3) Imaging findings consistent with AP, with at least two of these three required for diagnosis[3], as well as availability of serum phosphate at admission. Exclusion criteria included traumatic pancreatitis, acute exacerbation of chronic pancreatitis, age < 18 years, inaccessible medical records, and missing admission data.

For each patient, demographics (age, sex), etiology (e.g., gallstones, alcohol, hypertriglyceridemia, drugs, autoimmune, idiopathic), comorbidities, admission laboratory values, and clinical course were extracted from electronic health records into a standardized anonymized dataset. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Health Sciences, Kayseri City Hospital (Approval No. 2025/288) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Given the retrospective and de-identified nature of this study, the requirement for individual informed consent was waived by the ethics committee. Although patient admissions dated back to November 2023, ethical approval was obtained in early 2025 prior to database lock and analysis, in line with institutional policy for retrospective studies.

Serum phosphate (inorganic phosphorus) levels were measured spectrophotometrically in venous blood samples obtained upon hospital admission. Based on the institutional reference range (2.5-4.5 mg/dL), patients were classified as follows: Hypophosphatemia: < 2.5 mg/dL; Normophosphatemia: 2.5-4.5 mg/dL; Hyperphosphatemia: > 4.5 mg/dL.

These thresholds are consistent with definitions commonly used in standard medical references and in prior studies[4,9]. A spectrophotometric method was used to measure serum phosphate (Roche Cobas 8000 platform) with an analytical sensitivity of 0.1 mg/dL and an intra-assay coefficient of variation below 2%, ensuring consistent analytical performance.

Additional laboratory values obtained at admission included amylase, lipase, creatinine, urea, C-reactive protein (CRP), calcium, leukocyte count, hemoglobin, and hematocrit. Acute kidney injury (AKI) was defined according to the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria. No point-of-care or post-admission phosphate measurements were used for exposure classification.

AP severity was graded according to the revised Atlanta classification (2012)[9] as follows: Mild (no organ failure or local complications), moderately severe (transient organ failure < 48 hours and/or local complications), and severe (persistent organ failure ≥ 48 hours). Organ failure was assessed using the modified Marshall scoring system (score ≥ 2 in any organ system). Local complications, including pancreatic necrosis, pseudocysts, and abscesses, were confirmed using contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography.

In this cohort, SAP accounted for 25% of patients (n = 250), whereas mild and moderately severe cases accounted for 75% of patients. The primary outcome was 30-day all-cause mortality, ascertained through the hospital information system and cross-checked with national death notification records when available. Secondary outcomes included SAP, pancreatic necrosis, ICU admission, and length of hospital stay.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range), depending on distribution, and categorical variables as n (%). Group comparisons were performed using student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables, the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, and the Kruskal-Wallis test with post-hoc Dunn corrections for ≥ 3 groups.

To evaluate associations between admission phosphate category and clinical outcomes, multivariable logistic regression models were constructed, reporting adjusted OR with 95%CI. Covariates (age, sex, etiology, and comor

Patients without phosphate measurements at admission were excluded. For all other covariates, missingness was < 5%. Missing data were assumed to be missing at random and were handled using a complete-case approach. Because missingness was minimal, and to avoid bias or instability introduced by imputation, no imputation procedures were performed.

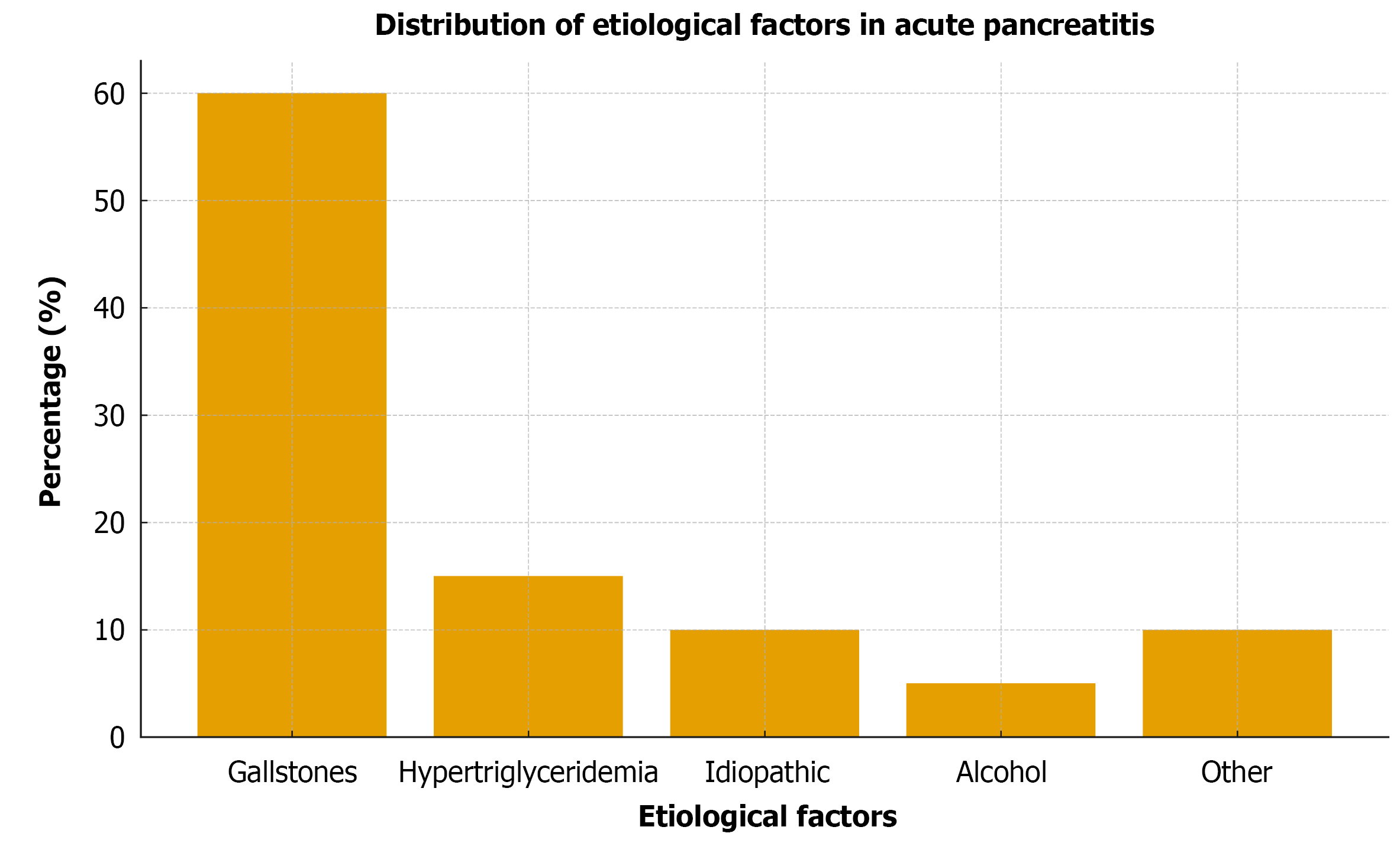

A total of 1000 patients were included [median age 55 years (IQR 45-64); 55% male]. Gallstones were the most common etiology (60%), followed by hypertriglyceridemia (15%), idiopathic AP (10%), and alcohol-related AP (5%), consistent with the etiological distribution reported in Turkey[2]. During the study period (November 2023-June 2025), 1000 admissions for AP were recorded at our tertiary center. However, hospital-wide denominators for total admissions were unavailable; therefore, the precise incidence could not be calculated and should be considered a limitation of this study. By admission phosphate category, 150 patients (15%) had hypophosphatemia (< 2.5 mg/dL), 750 (75%) had normophosphatemia (2.5-4.5 mg/dL), and 100 (10%) had hyperphosphatemia (> 4.5 mg/dL). Patients with hyperphosphatemia had a higher median age (60 years vs 53 years) and a higher proportion of males (65% vs 53%). Biliary etiology was less frequent (40%), whereas hypertriglyceridemia and other non-biliary causes were more common (overall P < 0.001 across groups; Table 1).

| Characteristic | Entire cohort (n = 1000) | Hypophosphatemia (< 2.5 mg/dL, n = 150) | Normophosphatemia (2.5-4.5 mg/dL, n = 750) | Hyperphosphatemia (> 4.5 mg/dL, n = 100) | P value |

| Age, median (IQR), years | 55 (45-64) | 54 (43–63) | 53 (44–62) | 60 (50–68) | 0.02 |

| Male sex | 550 (55.0) | 80 (53.3) | 400 (53.3) | 65 (65.0) | 0.03 |

| Gallstone-related AP | 600 (60.0) | 90 (60.0) | 480 (64.0) | 40 (40.0) | < 0.001 |

The mean admission phosphate level was 3.2 ± 1.1 mg/dL. Compared with other groups, patients with hyperphosphatemia had higher creatinine levels (1.8 ± 0.5 mg/dL vs 0.9 ± 0.3 mg/dL; P < 0.001) and higher CRP levels (167 mg/L vs 85 mg/L; P = 0.01), consistent with more frequent AKI according to KDIGO criteria.

SAP occurred in 25% of patients (n = 250). Among those with SAP, respiratory and renal failure were the most common organ failures, and pancreatic necrosis was present in 40% of patients. Admission phosphate category was significantly associated with all major outcomes (Table 2): SAP occurred in 40%, 20%, and 60% of patients with hypophosphatemia, normophosphatemia, and hyperphosphatemia, respectively (P < 0.001); pancreatic necrosis in 20%, 10%, and 50%, respectively (P < 0.001); ICU admission in 30%, 15%, and 70%, respectively (P < 0.001); and median length of stay was 10, 7, and 14 days, respectively (P < 0.001).

| Clinical outcome | Hypophosphatemia (< 2.5 mg/dL, n = 150) | Normophosphatemia (2.5-4.5 mg/dL, n = 750) | Hyperphosphatemia (> 4.5 mg/dL, n = 100) | P value |

| Severe acute pancreatitis | 60 (40) | 150 (20) | 60 (60) | < 0.001 |

| Pancreatic necrosis | 30 (20) | 75 (10) | 50 (50) | < 0.001 |

| ICU requirement | 45 (30) | 113 (15) | 70 (70) | < 0.001 |

| Length of hospital stay, median (days) | 10 | 7 | 14 | < 0.001 |

| 30-day mortality | 8 (5) | 23 (3) | 25 (25) | < 0.001 |

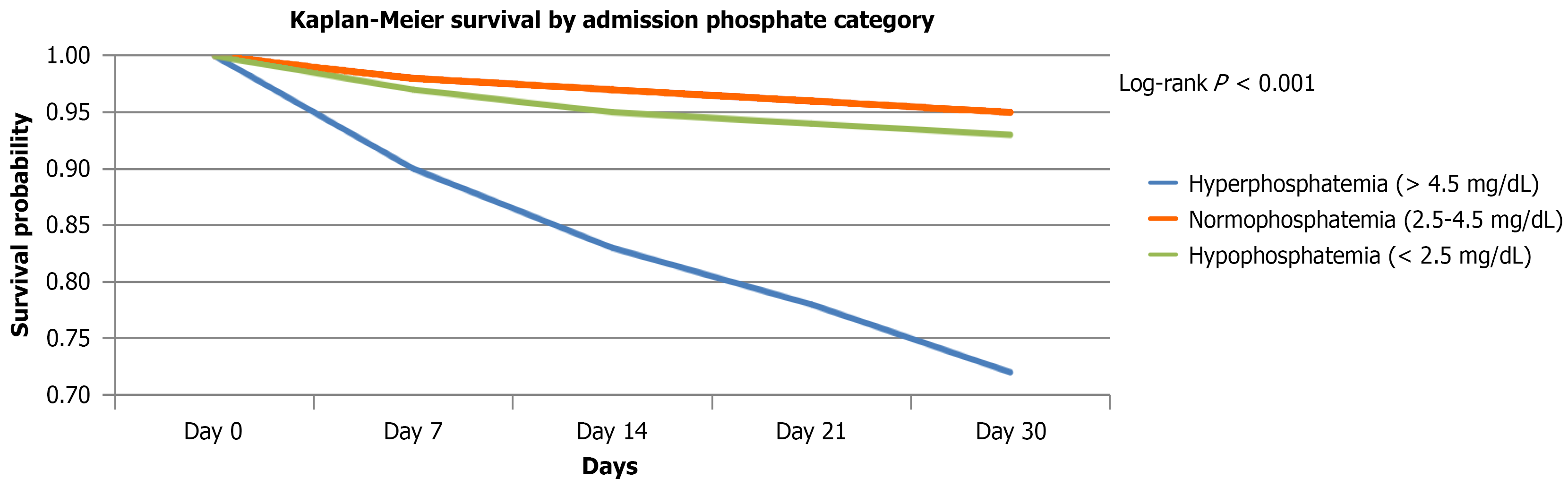

The etiologic distribution of AP showed gallstones as the leading cause (60%), followed by hypertriglyceridemia (15%), idiopathic AP (10%), alcohol (5%), and other causes (10%) (Figure 1). Disease severity according to the revised Atlanta classification showed that SAP represented 25% of cases, while mild and moderately severe cases accounted for 75% (Table 3). The 30-day all-cause mortality rate for the cohort was 4.2%. Mortality rates were 25%, 5%, and 3% for hyperphosphatemia, hypophosphatemia, and normophosphatemia, respectively. Figure 2 illustrates the 30-day mortality by phosphate category.

| Severity category (revised Atlanta Classification) | n (%) |

| Mild/moderately severe AP | 750 (75) |

| SAP | 250 (25) |

In multivariable logistic regression, hyperphosphatemia independently predicted 30-day mortality (adjusted OR 5.8, 95%CI: 2.9-11.5; P < 0.001) after adjustment for age, sex, comorbidities, etiology, and SAP. In an additional model including creatinine levels and AKI status, the association remained significant (adjusted OR 4.7, 95%CI: 2.1-10.3; P < 0.001), indicating that the prognostic value of phosphate is independent of renal dysfunction. Hyperphosphatemia also remained significantly associated with SAP, pancreatic necrosis, and ICU admission (Table 4). Hypophosphatemia did not independently predict mortality (adjusted OR 1.6; P = 0.40). When phosphate was modeled as a continuous variable, each 1 mg/dL increase was associated with a higher mortality risk (HR 1.51, 95%CI: 1.18-1.94).

| Outcome | Crude (hyper vs normo) (%) | Adjusted OR (95%CI) | P value |

| Severe AP | 60 vs 20 | 4.2 (2.3-7.8) | < 0.001 |

| Pancreatic necrosis | 50 vs 10 | 5.9 (3.1-11.2) | < 0.001 |

| ICU requirement | 70 vs 15 | 6.5 (3.8-12.0) | < 0.001 |

| 30-day mortality | 25 vs 3 | 5.8 (2.9-11.5) | < 0.001 |

In this large, 1000-patient cohort, we demonstrated that serum phosphate levels at admission are strongly associated with the clinical course of AP. Patients presenting with hyperphosphatemia have markedly higher rates of SAP and substantially increased risks of severe outcomes and mortality. Hyperphosphatemia remained an independent predictor of death after multivariable adjustment. In contrast, hypophosphatemia was associated with more frequent severe disease and complications but not with increased mortality, suggesting distinct underlying mechanisms.

The prognostic role of hyperphosphatemia has been highlighted in previous studies. Hedjoudje et al[5] identified serum phosphate measured within 24 hours as the strongest biochemical predictor of mortality in patients with AP admitted to the intensive care unit, while Fischman et al[6] confirmed an association between admission hyperphosphatemia and 30-day mortality. Importantly, our study provides several incremental contributions beyond previous reports that evaluated phosphate disturbances in AP. First, with 1000 consecutively hospitalized patients, it represents one of the largest single-center cohorts to date, substantially larger than the prior ICU-based studies by Hedjoudje et al[5] and Fischman et al[6], which focused on more selective and critically ill populations. Second, our cohort encompassed a broad and heterogeneous clinical spectrum, spanning both mild and SAP across a range of etiologies, allowing for a more generalizable assessment of phosphate-related risk. Third, unlike earlier analyses, we performed comprehensive multivariable adjustment, including renal function parameters (creatinine levels and AKI status). The association between hyperphosphatemia and 30-day mortality remained robust after these adjustments, demonstrating that phosphate elevation conveys prognostic information beyond renal dysfunction alone. Finally, by evaluating multiple clinically relevant endpoints (SAP, pancreatic necrosis, ICU admission, and mortality), our study offers an integrated assessment of the prognostic significance of admission phosphate levels and expands current understanding of their role in early risk stratification algorithms.

Similarly, a 2025 study demonstrated that hypophosphatemia is strongly associated with pancreatic necrosis in alcohol-related AP, suggesting that low phosphate levels may serve as an early biochemical marker of pancreatic injury[10]. Consistent with these observations, Nasir et al[10] reported that hypophosphatemia independently predicts pancreatic necrosis in alcohol-induced AP, reinforcing the concept that phosphate depletion may reflect early structural damage. Hypophosphatemia has also been implicated in adverse outcomes; Lee et al[7] demonstrated its association with SAP and prolonged hospitalization. Moreover, low serum phosphate levels may reflect increased cellular utilization during systemic inflammation, leading to an intracellular shift[4,9]. In our cohort, hypophosphatemia was associated with higher morbidity but not with increased mortality, possibly due to timely supportive care and close clinical monitoring. Consistent with our findings, early hypophosphatemia has been reported as an independent prognostic marker in AP[11]. Rare case reports have also described severe hypophosphatemia in both alcohol-related and complicated AP, further highlighting the clinical relevance of phosphate disturbances[12,13].

Mechanistically, hyperphosphatemia often reflects AKI and extensive tissue breakdown. In our study, patients with hyperphosphatemia had significantly higher creatinine levels, consistent with renal dysfunction, a key determinant of SAP according to the revised Atlanta classification[9]. Pancreatic necrosis and systemic tissue injury may also release intracellular phosphate into circulation, making hyperphosphatemia a potential early marker of multiorgan failure. Experimental data also demonstrate that phosphate levels can modulate the initiation and severity of pancreatitis, further supporting their mechanistic relevance in disease progression[14]. Notably, the predictive value of hyperphosphatemia persisted even after adjustment for renal function, suggesting that phosphate levels reflect broader metabolic derangements than kidney injury alone. These findings align with previous reports[15-18] and support the utility of phosphate as a readily measurable biochemical biomarker.

Emerging research has also explored novel biomarkers, such as the neutrophil CD64 index and microRNA profiles for early risk stratification, which may complement biochemical parameters such as phosphate in future multimodal prediction models[19].

Our findings also reflect the regional epidemiology of AP, with gallstones as the leading etiology and alcohol accounting for only 5% of cases, a distribution consistent with previously reported Turkish cohorts[2]. Although alcohol-related AP cases were limited in our study, recent data suggest that hypophosphatemia may help identify patients at increased risk of pancreatic necrosis in this subgroup[10]. Larger, multicenter studies are needed to further explore these relationships.

Strengths and limitations: The main strength of this study is its large sample size (n = 1000), representing one of the largest single-center cohorts to evaluate serum phosphate in AP. This design ensured uniform diagnostic criteria and clinical management, and the inclusion of both mild and severe cases enabled a comprehensive assessment across the disease spectrum. However, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the retrospective design precludes causal inference and limits adjustment for unmeasured confounders, such as baseline nutritional status, fluid resuscitation strategy, or phosphate supplementation. Second, only admission phosphate values were available, preventing evaluation of temporal phosphate trends during hospitalization. Emerging data suggest that dynamic phosphate monitoring may provide incremental prognostic value; for example, Han et al[8] demonstrated that early fluctuations in phosphate levels during hospitalization are associated with organ failure and increased mortality in acute pancreatitis. Third, the single-center design may limit generalizability. Additionally, serum phosphate levels are influenced by various physiological and pathological processes, including renal dysfunction, acid–base disturbances, sepsis, and catabolic states, some of which may not be fully documented in retrospective datasets. Collectively, these limitations underscore the need for prospective, multicenter studies with serial phosphate measurements to validate and extend our findings.

Admission hyperphosphatemia identifies a distinct subgroup of patients with AP who are at high risk for severe disease, ICU admission, and early mortality, whereas hypophosphatemia is associated with higher morbidity without increased mortality. Serum phosphate level is a simple, inexpensive, and actionable biomarker that may facilitate early risk stratification upon hospital admission and help refine early clinical decision-making strategies in AP.

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the staff of the Department of Gastroenterology at Kayseri City Hospital for their support during the data collection process.

| 1. | Banks PA, Freeman ML; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2379-2400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1181] [Cited by in RCA: 1179] [Article Influence: 59.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Öğütmen Koç D, Bengi G, Gül Ö, Özen Alahdab Y, Altıntaş E, Barutçu S, Bilgiç Y, Bostancı B, Cindoruk M, Çolakoğlu K, Duman D, Ekmen N, Eminler AT, Gökden Y, Günay S, Derviş Hakim G, Irak K, Kacar S, Kalkan İH, Kasap E, Köksal AŞ, Kuran S, Oruç N, Özdoğan O, Özşeker B, Parlak E, Saruç M, Şen İ, Şişman G, Tozlu M, Tunç N, Ünal NG, Ünal HÜ, Yaraş S, Yıldırım AE, Soytürk M, Oğuz D, Sezgin O. Turkish Society of Gastroenterology: Pancreas Working Group, Acute Pancreatitis Committee Consensus Report. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2024;35:S1-S44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tenner S, Baillie J, DeWitt J, Vege SS; American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology guideline: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1400-15; 1416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1232] [Cited by in RCA: 1429] [Article Influence: 109.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 4. | Ruiz Rebollo ML, Muñoz Moreno MF, Piñerua Gonsálvez JF, Rizzo Rodriguez MA. Serum Phosphate and Its Association With Severity in Acute Alcoholic Pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2023;52:e258-e260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hedjoudje A, Farha J, Cheurfa C, Grabar S, Weiss E, Badurdeen D, Kumbhari V, Prat F, Levy P, Piton G. Serum phosphate is associated with mortality among patients admitted to ICU for acute pancreatitis. United European Gastroenterol J. 2021;9:534-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Fischman M, Elias A, Klein A, Cohen Y, Levy Y, Azzam ZS, Ghersin I. The association between phosphate level at admission and early mortality in acute pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2023;58:1157-1164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lee JP, Darlington K, Henson JB, Kothari D, Niedzwiecki D, Farooq A, Liddle RA. Hypophosphatemia as a Predictor of Clinical Outcomes in Acute Pancreatitis: A Retrospective Study. Pancreas. 2024;53:e3-e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Han Y, Chen F, Wei W, Zeng J, Song Y, Wang Z, Cao F, Wang Y, Xu K, Ma Z. Association between phosphorus-to-calcium ratio at ICU admission and all-cause mortality in acute pancreatitis: Insights from the MIMIC-IV database. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2025;32:228-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4932] [Cited by in RCA: 4731] [Article Influence: 363.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (48)] |

| 10. | Nasir SA, Pandya D, Chambers E, Zubair S, Kanneganti SP, Hopkins R, Mangla R, Anand N. Hypophosphatemia as a Predictor of Pancreatic Necrosis in Acute Alcohol-induced Pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2025;54:e460-e465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Stewart CF, Adeniran EA, Yadav D, Gorelick FS, Liddle RA, Wu B, Pandol SJ, Jeon CY. Early Hypophosphatemia as a Prognostic Marker in Acute Pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2024;53:e611-e616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | 12 Al-Anbagi U, Usman S, Saad A, Nashwan AJ. Severe Hypophosphatemia in Alcohol-Induced Acute Pancreatitis: A Case Report. Cureus. 2023;15:e34149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mahdi A, Mahdi M, Abdelfattah OM, Eid F. Acute Chest Pain in an Acute Complicated Pancreatitis with Severe Hypophosphatemia. Kans J Med. 2022;15:383-385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Farooq A, Hernandez L, Swain SM, Shahid RA, Romac JM, Vigna SR, Liddle RA. Initiation and severity of experimental pancreatitis are modified by phosphate. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2022;322:G561-G570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Li K, Cao S, Qin K, Luo J, Ding N. Serum Phosphate is a Biomarker for In-hospital and 30-day Mortality in Patients With Acute Pancreatitis Based on the MIMIC-IV Database. Pancreas. 2025;54:e474-e481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wu BU, Johannes RS, Sun X, Tabak Y, Conwell DL, Banks PA. The early prediction of mortality in acute pancreatitis: a large population-based study. Gut. 2008;57:1698-1703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 451] [Cited by in RCA: 573] [Article Influence: 31.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 17. | Rizos E, Alexandrides G, Elisaf MS. Severe hypophosphatemia in a patient with acute pancreatitis. JOP. 2000;1:204-207. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Shao M, Wu L, Huang X, Ouyang Q, Peng Y, Liu S, Xu X, Yi Q, Liu Y, Li G, Ning D, Wang J, Tan C, Huang Y. Neutrophil CD64 index: a novel biomarker for risk stratification in acute pancreatitis. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1526122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Liao Y, Zhang W, Huang Z, Yang L, Lu M. Diagnostic and prognostic value of miR-146b-5p in acute pancreatitis. Hereditas. 2025;162:93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/