Published online Dec 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i12.111450

Revised: July 20, 2025

Accepted: October 11, 2025

Published online: December 27, 2025

Processing time: 178 Days and 14.9 Hours

Distribution of the colonic diverticula differs in different populations, and right-sided colon diverticulitis (RCD) and left-sided colon diverticulitis (LCD) manifest distinct clinical features. Complicated diverticulitis (CD) mostly requires hospita

To evaluate the clinical features of CD, display the differences according to colonic localizations, and present treatment approaches.

This was a retrospective study from a single centre analysing data from a prospective database. The 253 patients with history of hospitalization for CD were included and divided into two groups: RCD and LCD. To compare the differences between the two groups, the Student’s t-test was used when the parametric test prerequisites were fulfilled, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used when such requirements were not fulfilled.

The 208 (82.2%) patients were found to have LCD, and 45 (17.8%) had RCD. The majority of the patients had Hinchey 1A diverticulitis (49.8%). Male gender was significantly more common in patients who underwent surgery for LCD. While persistent abdominal pain was the main prior finding in the conservative treatment of both locali

Although diverticulitis is a benign condition, the need for an individualized and evidence-based approach makes management challenging. Localization of the disease has an important role in determining the appropriate treatment.

Core Tip: Diverticular disease has a globally increasing incidence. Most of the current studies on diverticulitis refer to left colonic diverticulitis. However, right-sided colon diverticulitis (RCD) and left-sided colon diverticulitis (LCD) manifest distinct features. This retrospective study consisted of 253 patients with complicated diverticulitis and compared the characteristics and treatment approaches of RCD and LCD. Age, Charlson comorbidity index, prior complication, Hinchey stage, number of episodes, and the mean length of hospital stay were significantly different between RCD and LCD. The presence of an accompanying lesion during elective colonoscopy was statistically significant among LCD. Although conservative treatment was adequate in most RCD, there is still no standard treatment management in LCD, since the course of the disease differs among individuals.

- Citation: Acar T, Sür Y, Acar N, Tekindal MA, Dilek ON. Does localization change management in complicated right and left-sided diverticulitis? World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(12): 111450

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i12/111450.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i12.111450

Diverticular disease, which used to be attributed as a disease of Western populations, has an increasing incidence all around the world because of globalization and industrialization. Distribution of the colonic diverticula differs according to the population. Asian populations have a predominance for developing right colon diverticula with the rate of 70%-85%, while Western populations have for left colon diverticula with the rate of 80%-90%[1-3].

Although it usually remains asymptomatic, 15%-20% of the patients with diverticular disease develop complications and become symptomatic[4]. These complications (abscess, fistula, free perforation, stricture, and bleeding) may threaten life, unless they are timely and properly intervened. Complicated diverticulitis (CD) mostly requires hospitalization and can be treated within a spectrum from observation to surgery. Treatment choice differs depending on the patient’s gene

Treatment of CD has been altered in recent years, favouring less aggressive approaches and minimally invasive interventions[5]. Although management of the cases requiring emergency surgery is quite clear, indications for elective surgery in patients who recovered from an episode of CD are still vague.

This study mainly aimed to evaluate the clinical features of CD from a single-centre, display the differences according to colonic localizations, and present the treatment approaches. In addition, secondary endpoints were determined as demographic and clinical features affecting the surgical decision making.

The retrospective study protocol was approved by the institutional Ethics Committee (No. 619). A written informed consent was obtained from each patient. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, revised in 2013.

Patients with history of hospitalization for diverticulitis between January 2015 and December 2019 in our department of general surgery were evaluated. The median duration of follow-up for all participants was 23.2 months.

The inclusion criteria were: (1) To be diagnosed with CD (Hinchey stage 1A, 1B, 2, 3, 4); (2) To be treated by hospitalization; and (3) To undergo colonoscopy (preoperative, intraoperative or during the follow-up).

Exclusion criteria were: (1) To be diagnosed with uncomplicated diverticulitis (Hinchey stage 0); (2) To receive outpatient treatment; (3) To have rectum diverticulitis; (4) The absence of a current colonoscopy; and (5) Lacking follow-up data.

Medical records of 328 patients with CD were retrospectively examined. Among these 328 patients, 253 with available long-term follow-up data were included in the study. Follow-up data were collected from the electronic follow-up platform of our hospital.

The following parameters were analyzed for all patients: Age, gender, Charlson comorbidity index (CCI)[6], modified Hinchey classification stage[7], the presence of immunosuppression [type 1 diabetes and autoimmune diseases (systemic lupus erythematosus, autoimmune hepatitis or rheumatoid arthritis)], number of previous episodes, treatment choice (conservative/surgical), operative condition (emergency/elective), type of the surgical procedure, presence of additional lesions in colonoscopy, length of hospital stay, and early and late-term outcomes (morbidity/mortality).

The diagnosis and staging of CD were performed by clinical, imaging (ultrasonography and/or computed tomogra

Patients who were observed conservatively underwent colonoscopy 6-10 weeks after discharge, and those who had surgery underwent colonoscopy either intraoperatively or 6-12 months after the operation. Objectives of the colonoscopy were to confirm the diagnosis, to detect additional pathologies, to determine the resection margin, and/or to check the anastomosis line.

Patients with stable vital signs and without any signs of peritonitis were treated conservatively. Conservative ma

Patients, who developed complications that could not be treated conservatively or with minimally invasive interven

Antibiotic prophylaxis (2 g of cefazolin) was administered to all patients scheduled for surgery and bowel preparation was given for elective cases. Surgical procedures included three techniques: (1) Diversion with a proximal colostomy and drainage of the perforated area without resection (DD); (2) Colectomy with end colostomy (Hartmann’s procedure); and (3) Colectomy with anastomosis (with or without diverting ileostomy). Colectomy was fulfilled with open or laparoscopic approach, and only the inflammatory and hypertrophic segment causing CD was resected[8,9]. The term “colectomy” comprised ileocecal resection, right hemicolectomy, sigmoidectomy and anterior resection. End-to-side anastomosis was performed in patients undergoing ileocecal resection and right hemicolectomy, while end-to-end anastomosis was preferred after all other resections. Our study is an observational and cross-sectional study.

For discrete and continuous variables, descriptive statistics (mean, SD, median, minimum value, maximum value, and percentile) were given. In addition, the homogeneity of the variances, which is one of the prerequisites of parametric tests, was checked through Levene’s test. The assumption of normality was tested via the Shapiro-Wilk test. To compare the differences between the two groups, the Student’s t-test was used when the parametric test prerequisites were fulfilled, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used when such prerequisites were not fulfilled. χ2 test was used for determining the relationships between two discrete variables. When the expected sources were less than 20%, values were determined through the Monte Carlo Simulation Method to include such sources in analysis[10].

An equivalence test of means using two one-sided tests on data from a parallel-group design with sample sizes of 43 in the RCD group and 196 in the LCD group achieves 80.078% power at a 5% significance level when the true difference between the means is 0.00, the standard deviation is 8.70, and the equivalence limits are -4.50 and 4.50.

The data were evaluated via SPPS 20 (IBM Corp. Released 2011. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). P < 0.05 was taken as significance levels.

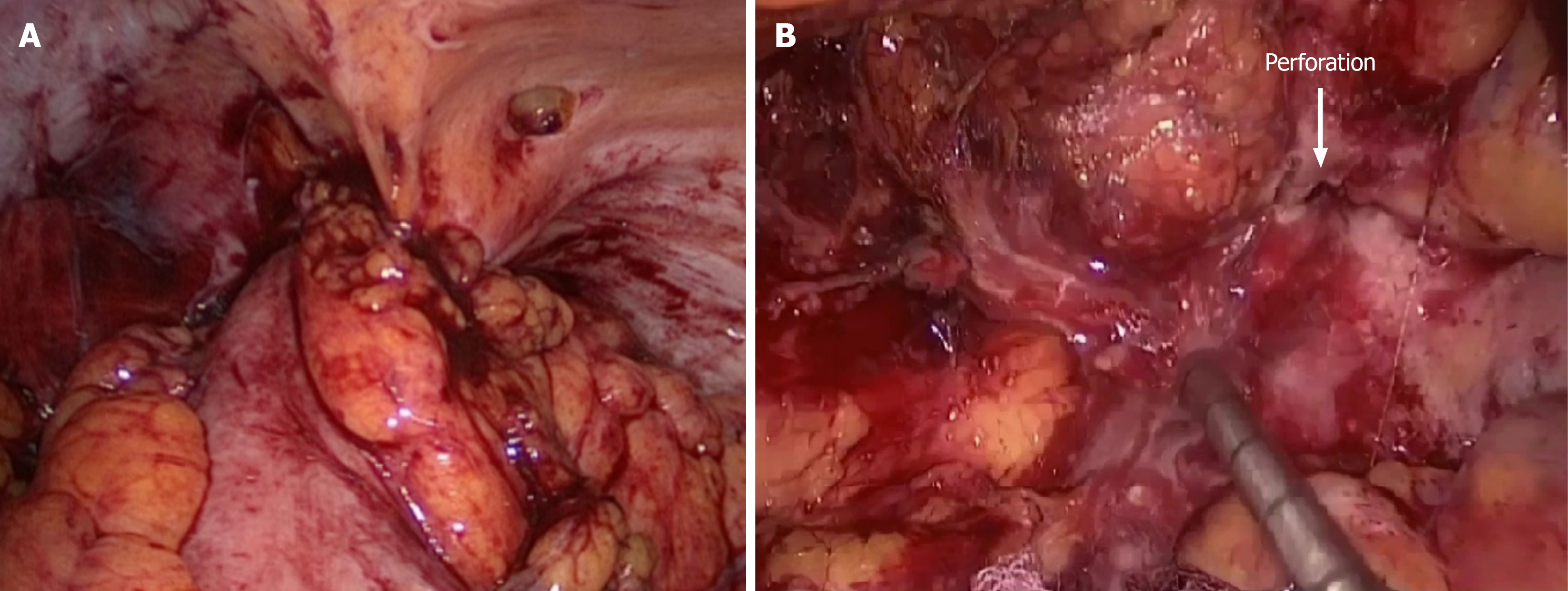

Demographic and clinical characteristics of all patients (Table 1). Among the 253 patients included in the study, 127 (50.2%) were male, and the mean age was 59.59 ± 14.97 years (21-90 years). When the patients were divided into three subgroups by age, most patients were between the sixth and seventh decades of life (44.2%). Mean CCI score was 2.28 ± 1.99. Majority of the patients were found to have LCD (82.2%). Persistent abdominal pain (54.2%) without any major complication was the most common prior finding, and followed by perforation (23.3%), abscess (13.8%), obstruction (3.2%), bleeding (2.4%), peritonitis (2%) and fistula (1.2%), respectively. In terms of modified Hinchey classification, most patients had Hinchey 1A diverticulitis (49.8%). Hinchey 1B, 2, 3 and 4 were diagnosed in 19.8%, 17.4%, 11.5% and 1.6% of the patients, respectively (Figure 1). In addition, 216 patients (85.4%) had their first episode of diverticulitis, while eight (3.2%) had at least three episodes.

| Item | Value |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Female | 126 (49.8) |

| Male | 127 (50.2) |

| Age (year; mean) | 59.59 ± 14.97 (21-90) |

| Age group (year), n (%) | |

| ≤ 50 | 70 (27.7) |

| 50-70 | 112 (44.2) |

| ≥ 70 | 71 (28.1) |

| CCI (mean) | 2.28 ± 1.99 |

| Immunosuppression, n (%) | 17 (6.7) |

| Localization, n (%) | |

| Right colon | 45 (17.8) |

| Left colon | 208 (82.2) |

| Prior finding, n (%) | |

| Abscess | 35 (13.8) |

| Bleeding | 6 (2.4) |

| Fistula | 3 (1.2) |

| Obstruction | 8 (3.2) |

| Perforation | 59 (23.3) |

| Peritonitis | 5 (2) |

| Sole persistent abdominal pain | 137 (54.2) |

| Hinchey, n (%) | |

| 1A | 126 (49.8) |

| 1B | 50 (19.8) |

| 2 | 44 (17.4) |

| 3 | 29 (11.5) |

| 4 | 4 (1.6) |

| Number of episodes, n (%) | |

| 1 | 216 (85.4) |

| 2 | 29 (11.5) |

| ≥ 3 | 8 (3.2) |

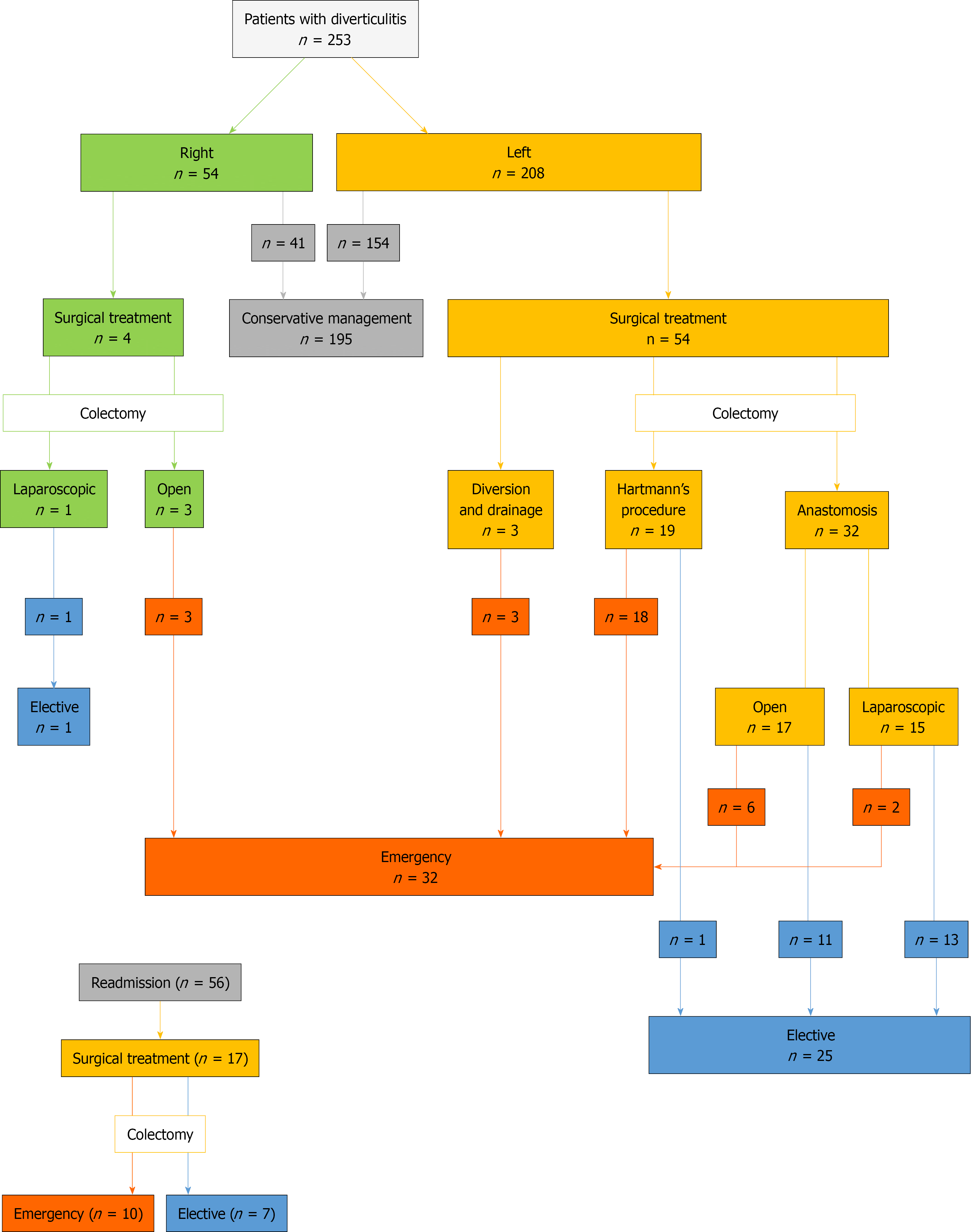

Conservative treatment was adequate in majority of the patients (77.1%). PD was performed in 39 patients (15.4%). Three (7.7%) of them failed and eventually required emergency surgery. Readmission rate within six weeks after discharge among the patients who received conservative treatment was 28.7% (n = 56). Conservative treatment failed in 17 of them, and these patients underwent surgery.

A total of 32 patients (12.6%) had to undergo emergency surgery, while 26 (10.3%) underwent elective surgery. Developing a complication (mostly abscess and free perforation) and/or presence of a concomitant malignancy were the most common indications for surgery (87.9%). The most preferred surgical procedure was colectomy (with stoma or anastomosis) (94.8%), and three patients underwent DD. Postoperative complications were encountered in 23 (39.7%) patients. Surgical site infection (30.7%) and incisional hernia (21.7%) were the most common early and late complications, respectively. Management and fate of the patients are summarized in Table 2.

| Item | Value |

| Percutaneous drainage, n (%) | 39 (15.4) |

| Type of treatment, n (%) | |

| Conservative | 195 (77.1) |

| Surgical | 58 (22.9) |

| Emergency | 32 (12.6) |

| Elective | 26 (10.3) |

| Surgical indication, n (%) | |

| Complication or concomitant malignancy1 | 51 (87.9) |

| Recurrent episodes | 7 (12.1) |

| Surgery type, n (%) | |

| DD | 3 (5.2) |

| Hartmann’s procedure | 19 (32.8) |

| Colectomy with anastomosis | 36 (62) |

| Open | 20 (34.4) |

| Laparoscopic | 16 (27.6) |

| Postoperative complication, n (%) | 23 (39.7) |

| Early period | 14 (60.9) |

| SSI | 7 (30.7) |

| Anastomosis leak | 3 (13) |

| Intraabdominal abscess | 2 (8.7) |

| Evisceration | 1 (4.3) |

| Brid ileus | 1 (4.3) |

| Late period | 9 (39.1) |

| Incisional hernia | 5 (21.7) |

| Parastomal hernia | 3 (13) |

| Anastomosis stenosis | 1 (4.3) |

| Colonoscopic finding, n (%) | |

| Sole diverticul/diverticulitis | 219 (86.6) |

| Polyp(s) | 23 (9.1) |

| Malignancy or suspected malignancy | 10 (4) |

| Ulcerative colitis | 1 (0.4) |

| The mean length of hospital stays (day; range) | 5.15 ± 2.82 (2-23) |

| Mortality, n (%) | 3 (1.2) |

All patients underwent an early or late colonoscopies after the hospitalization. No additional findings were detected except diverticula in majority of the patients (86.6%). Polyp (9.1%), malignancy (4%) and ulcerative colitis (0.4%) were detected in the rest of the patients. The mean length of hospital stay was 5.15 ± 2.82 days. Mortality occurred in three patients who had high CCI score and had undergone emergency surgery due to LCD.

When the clinical features of RCD and LCD were compared, age (mean and distribution), CCI, prior finding, Hinchey stage, number of the episodes and the mean length of hospital stay were found to be statistically significant (P < 0.01; Table 3). Patients with RCD were significantly younger with the mean age of 49.27 ± 15.54 years, and these patients’ mean CCI score were lower than LCD’s. Regarding prior complication, sole persistent pain was significantly more common in RCD (71.1%), while bleeding or fistula did not occur in any of the cases with RCD. On the other hand, perforation, the second most common complication in the series, had significantly higher incidence among LCD (27.9%). Hinchey 1A disease was more common among RCD (66.7%), while more advanced Hinchey stages were encountered more frequently in LCD. All patients with RCD had only one episode of diverticulitis. The mean length of hospital stay was significantly shorter in RCD (3.69 ± 1.16 days). No significant difference was found between the groups in terms of gender, status of immunosuppression, PD, type of the treatment, and performed surgical procedure.

| Right colon (n = 45) | Left colon (n = 208) | P value | |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Female | 21 (46.7) | 105 (50.5) | 0.643 |

| Male | 24 (53.3) | 103 (49.5) | |

| Age (year; mean) | 49.27 ± 15.54 | 61.83 ± 13.91 | 0.001 |

| Age group (year), n (%) | |||

| ≤ 50 | 23 (51.1) | 47 (22.6) | 0.001 |

| 50-70 | 17 (37.8) | 95 (45.7) | |

| ≥ 70 | 5 (11.1) | 66 (31.7) | |

| CCI (mean) | 1.02 ± 1.42 | 2.57 ± 2 | 0.001 |

| Immunosuppression, n (%) | 3 (6.7) | 14 (6.7) | 0.988 |

| Prior finding, n (%) | |||

| Abscess | 10 (22.2) | 25 (12) | 0.006 |

| Bleeding | - | 6 (2.9) | |

| Fistula | - | 3 (1.4) | |

| Obstruction | 1 (2.2) | 7 (3.4) | |

| Perforation | 1 (2.2) | 58 (27.9) | |

| Peritonitis | 1 (2.2) | 4 (1.9) | |

| Sole persistent abdominal pain | 32 (71.1) | 105 (50.5) | |

| Hinchey, n (%) | |||

| 1A | 30 (66.7) | 96 (46.2) | 0.016 |

| 1B | 11 (24.4) | 39 (18.8) | |

| 2 | 2 (4.4) | 42 (20.2) | |

| 3 | 2 (4.4) | 27 (13) | |

| 4 | - | 4 (1.9) | |

| Number of episodes, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 45 (100) | 171 (82.2) | 0.009 |

| 2 | - | 29 (13.9) | |

| ≥ 3 | - | 8 (3.8) | |

| Percutaneous drainage, n (%) | 2 (4.4) | 37 (17.8) | 0.025 |

| Type of treatment, n (%) | |||

| Medical | 41 (91.1) | 154 (74) | 0.041 |

| Surgical | 4 (8.9) | 54 (26) | |

| Emergency | 3 (6.7) | 29 (13.9) | |

| Elective | 1 (2.2) | 25 (12.1) | |

| Performed surgery, n (%) | |||

| DD | - | 3 (5.6) | 0.08 |

| Hartmann’s procedure | - | 19 (35.1) | |

| Colectomy with anastomosis | |||

| Open | 3 (75) | 17 (31.5) | |

| Laparoscopic | 1 (25) | 15 (27.8) | |

| Postoperative complication, n (%) | - | 23 (26.1) | 0.697 |

| The mean length of hospital stays (day) | 3.69 ± 1.16 | 5.48 ± 2.98 | 0.001 |

| Mortality, n (%) | - | 3 (1.4) | - |

General management of patients is shown in Figure 2, and Table 4 compares conservative treatment and surgery in RCD and LCD. Gender, status of immunosuppression, presence of an accompanying lesion during colonoscopy and the mean length of hospital stay were found to be statistically significant between observation and surgery groups in LCD (P < 0.01). Additionally, at prior complication and Hinchey stage, there were significant differences between observation and surgery groups in both RCD and LCD (P < 0.01). Male gender was significantly more common in patients who underwent surgery for LCD, while female gender was more frequent in LCD patients who underwent conservative treatment. The incidence of immunosuppression, which was 9.3% in LCD patients who underwent surgery, was also significantly higher than LCD patients who underwent observation. However, the status of immunosuppression did not have any statistical significance in RCD, since all three (7.3%) immunosuppressive patients were managed with conservative treatment. Among the RCD patients, the most common prior complication was persistent abdominal pain (78%) in conservative treatment group, and abscess (75%) in surgery group. Persistent abdominal pain (63.6%) was also the most common prior complication in conservative treatment group of LCD, however perforation (48.1%) was the most common in surgery group.

| Right colon (n = 45) | Left colon (n = 208) | |||||

| Observation (n = 41) | Surgery (n = 4) | P value | Observation (n = 154) | Surgery (n = 54) | P value | |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||||

| Female | 20 (48.8) | 1 (25) | 0.363 | 88 (57.1) | 17 (31.5) | 0.001 |

| Male | 21 (51.2) | 3 (75) | 66 (42.9) | 37 (68.5) | ||

| Age (year; mean) | 49.32 ± 15.65 | 48.75 ± 16.58 | 0.95 | 61.47 ± 14.09 | 62.87 ± 13.43 | 0.52 |

| Age group, n (%) | 0.957 | |||||

| ≤ 50 | 21 (51.2) | 2 (50) | 0.621 | 35 (22.7) | 12 (22.2) | |

| 50-70 | 16 (39) | 1 (25) | 71 (46.1) | 24 (44.4) | ||

| ≥ 70 | 4 (9.8) | 1 (25) | 48 (31.2) | 18 (33.4) | ||

| CCI (mean) | 1.02 ± 1.44 | 1 ± 1.41 | 0.97 | 2.5 ± 1.93 | 2.75 ± 2.18 | 0.42 |

| Immunosuppression, n (%) | 3 (7.3) | - | 0.575 | 9 (5.8) | 5 (9.3) | 0.001 |

| Prior finding, n (%) | ||||||

| Abscess | 7 (17.1) | 3 (75) | 0.001 | 16 (10.4) | 9 (16.7) | 0.001 |

| Bleeding | - | - | 5 (3.2) | 1 (1.9) | ||

| Fistula | - | - | - | 3 (5.6) | ||

| Obstruction | 1 (2.4) | - | 3 (1.9) | 4 (7.4) | ||

| Perforation | 1 (2.4) | - | 32 (20.8) | 26 (48.1) | ||

| Peritonitis | - | 1 (25) | - | 4 (7.4) | ||

| Sole persistent abdominal pain | 32 (78) | - | 98 (63.6) | 7 (13) | ||

| Hinchey, n (%) | ||||||

| 1A | 30 (73.2) | - | 0.001 | 92 (59.7) | 4 (7.4) | 0.001 |

| 1B | 10 (24.4) | 1 (25) | 34 (22.1) | 5 (9.3) | ||

| 2 | 1 (2.4) | 1 (25) | 24 (15.6) | 18 (33.3) | ||

| 3 | - | 2 (50) | 4 (2.6) | 23 (42.6) | ||

| 4 | - | - | - | 4 (7.4) | ||

| Number of episodes, n (%) | - | |||||

| 1 | 41 (100) | 4 (100) | 141 (91.6) | 30 (55.6) | 0.389 | |

| 2 | - | - | 13 (8.4) | 16 (29.6) | ||

| ≥ 3 | - | - | - | 8 (14.8) | ||

| Percutaneous drainage, n (%) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (25) | 0.037 | 23 (14.9) | 14 (25.9) | 0.069 |

| Accompanying lesion on colonoscopy, n (%) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (25) | 21 (13.5) | 11 (19.4) | ||

| Polyp | 1 (2.4) | - | 0.005 | 19 (12.3) | 3 (5.6) | 0.001 |

| Malignancy | - | 1 (25) | 1 (0.6) | 8 (14.8) | ||

| Ulcerative colitis | - | - | 1 (0.6) | - | ||

| The mean length of hospital stays (day), (range) | 3.49 ± 0.84 | 5.75 ± 2.06 | 0.11 | 4.68 ± 1.5 | 7.74 ± 4.6 | 0.001 |

| Mortality, n (%) | - | - | - | - | 3 (5.6) | - |

This study displayed several differences in clinical features between RCD and LCD, and in their managements. Younger age, lower Hinchey stages and significantly higher incidences of conservative treatment in RCD, and higher incidence of surgery in male and immunosuppressive LCD patients were the main endpoints.

Right and left colon diverticula have distinct backgrounds and pathophysiology which also affect their clinical manifestation. Right-sided diverticula are usually congenital, and for this reason, becomes symptomatic in younger ages. On the other hand, left-sided diverticula are acquired, and their prevalence increases by the advancing age. In their studies comparing the clinical features of the patients with right and left-sided diverticulitis, Lee et al[11] and Soh et al[12] reported the mean ages of RCD patients as 41.4 and 45.7, respectively, which were significantly younger than LCD patients. In addition, in the meta-analysis by Hajibandeh et al[13], it was determined that RCD affected younger patients. Left colon diverticulitis has more tendency to perforation than RCD since LCD mainly develops from pseudo-diverticula lacking muscularis propria and serosal layers. This also results in more advanced Hinchey stages in LCD than RCD[11]. All these well-known demographic and clinical data were compatible with our results.

In addition to the previous studies, our study also demonstrated that patients with RCD had lower CCI score, a smaller number of episodes and shorter mean length of hospital stay[11,12].

Management of CD differs according to Hinchey stage (severity of the disease), type of the complications, and underlying comorbid conditions. Conservative treatment with/without PD will be more beneficial in RCD, since they have lower Hinchey stages[13,14]. Zuckerman et al[15] published that 76.6% of RCD patients benefited from conservative treatment. This situation is a little more complicated in LCD. Generally, antibiotics with/without PD are usually adequate in Hinchey 1 and 2 cases, while Hinchey 3 and 4 require surgery[13,16]. PD is an intermediate treatment modality between medical treatment and surgery. This modality provides the opportunity for performing an elective single-stage operation in the conditions which usually require a stoma and further multiple surgical interventions[17]. Current guidelines have recommended PD for the abscesses larger than 3 cm, those that do not display regression with antibiotics, and/or in the presence of patient deterioration[18,19]. In their study of 447 patients with diverticular abscess, Lambrichts et al[20] reported that abscesses larger than 3 cm were more likely to experience treatment failure (26.8%), and abscesses 5 cm or larger were associated with the need for surgery (8.9%). In the retrospective study of Elagili et al[21], selected patients treated with initial antibiotics alone vs PD were compared, and medical treatment and PD were found to fail in 25% and 18% of the patients, respectively.

In our study, the percentage of the patients who were treated conservatively was 91.1% and 74% in RCD and LCD, respectively. This difference was due to Hinchey 1 disease was significantly more common among RCD. Conservative treatment was successful in all RCD patients, while it failed in 13 patients (8.3%) with LCD. PD was performed in two patients (4.4%) with RCD and 37 patients (17.8%) with LCD. Three (7.7%) of them failed and eventually required emergency surgery.

Indications for emergency surgery have been quite clear since early 1900s. Patients with diffuse peritonitis (Hinchey 3 and 4 disease) or those who do not show any improvement under the conservative treatment are the main candidates for emergency surgery[19]. Resection with anastomosis is almost a standard surgical technique in RCD. However, which surgical technique to choose can be confusing in some conditions, since there is not a gold standard treatment for LCD. Many studies in the literature have demonstrated both the advantages and the disadvantages of peritoneal lavage, Hartmann’s procedure, resection with anastomosis and anastomosis with a diverting stoma[16]. Hartmann’s procedure is a traditional and most performed technique in the emergency settings. It is considered as a fast and leery approach especially in patients with comorbidities and poor general condition. Main handicap concerning Hartmann’s procedure is that the stoma reversal cannot be achieved in 30%-40% of the patients[22,23]. Oberkofler et al[24], favoured primary anastomosis with diverting ileostomy over Hartmann’s procedure in patients with perforated diverticulitis based on the facts that stoma reversal rate was higher in ileostomy group and there was no difference in complication and mortality rates. DIVERTI trial in 2017 reported similar outcomes showing that Hartmann’s procedure and primary anastomosis with a diverting stoma had similar morbidity and mortality[25]. In addition, 2019 LADIES trial showed that primary anastomosis for Hinchey 3 and 4 diseases is a safe approach in hemodynamically stable, immunocompetent patients younger than 85 years[20]. Primary anastomosis in Hinchey 3 and 4 diseases has been moderately-strongly recommended in recent ASCRS guidelines (2020), once it was weakly recommended in 2014[19]. The preference of diverting ileostomy, on the other hand, has been left to the surgeon. After all, Hartmann’s procedure is still indispensable especially in high-risk patients[26].

In our series, among the 32 patients undergoing emergency surgery, the rates of Hartmann’s procedure, primary anastomosis and DD were 56.2%, 34.4%, and 9.4%, respectively. It was not possible to compare RCD and LCD in terms of surgical techniques, since only three patients underwent emergency surgery in RCD group. Nevertheless, it was obtained that all patients from RCD group underwent resection and primary anastomosis. More frequent application of Hartmann’s procedure can be explained with relatively high mean CCI score of 2.88 and the fact that they were mostly performed in the past years. Hartmann colostomy reversal could not be achieved in four patients (21.1%) due to the patient preference and high-risk comorbidities.

Readmission rate after conservatively treated CD has been reported between 9.6%-61%[27,28]. El-Sayed et al[29] published that 11.2% of the non-operatively treated diverticulitis patients developed recurrence, and that 55.5% of them did not require further surgical intervention. Same study showed that complicated cases without PD had the highest risk for the readmission. In our study, readmission rate was 28.7% among 195 patients who underwent conservative treatment, and 69.6% of them responded conservative treatment once more.

Patients with CD carry a risk for malignancy[30]. Sharma et al[31] showed that the risk of malignancy was 11% in patients with CD and 0.7% in patients with uncomplicated diverticulitis. Therefore, after the recovery of acute CD episode, routine endoscopic evaluation should be performed to confirm the diagnosis and evaluate additional pathologies if patient has not undergone a recent colonoscopy[19]. In our series, polyp and malignancy/suspected malignancy was detected in 23 (9.1%) and 10 (4%) patients, respectively.

Its retrospective design and the fact that reflecting the outcomes of a single-centre were the main limitations of this study. Data regarding the smoking and/or alcohol consumption is not available. In addition, due to the small sample size of the RCD patients undergoing surgery, an adequate statistical comparison could not be obtained. However, this is the first study from Europe comparing the right and left-sided CD and the second largest (the number of patients) in English-language literature. Additionally, comprising patients from Türkiye who can be genetically defined as Eurasian and from a centre which has patients from both rural and urban areas makes this study unique.

In conclusion, although conservative treatment is adequate in most RCD, there is still no standard treatment management in LCD, since the severity and course of the disease differs among individuals. This situation also affects the need for elective surgery. While elective surgery is required less often in RCD due to lower rates of recurrence, complications and accompanying malignancy; LCD is more prone to elective surgery due to severe clinical symptoms, and high rates of recurrence and readmission. Thus, stoma requirement is also reduced, and better postoperative results are obtained with less invasive methods (laparoscopic or robotic).

Izmir Katip Celebi University Faculty of Medicine, Izmir Ataturk Training and Research Hospital, kindly supported this work.

| 1. | Song ME, Jung SA, Shim KN, Song EM, Kwon KJ, Kim HI, Yoon SY, Cho WY, Kim SE, Jung HK, Moon IH. [Clinical characteristics and treatment outcome of colonic diverticulitis in young patients]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2013;61:75-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tursi A, Scarpignato C, Strate LL, Lanas A, Kruis W, Lahat A, Danese S. Colonic diverticular disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6:20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 28.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Kaise M, Nagata N, Ishii N, Omori J, Goto O, Iwakiri K. Epidemiology of colonic diverticula and recent advances in the management of colonic diverticular bleeding. Dig Endosc. 2020;32:240-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tursi A, Papa A, Danese S. Review article: the pathophysiology and medical management of diverticulosis and diverticular disease of the colon. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:664-684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dean M, Kessler H, Gorgun E. Surgical outcomes for diverticulitis in young patients: results from the NSQIP database. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:4953-4956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32099] [Cited by in RCA: 39731] [Article Influence: 1018.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hinchey EJ, Schaal PG, Richards GK. Treatment of perforated diverticular disease of the colon. Adv Surg. 1978;12:85-109. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Acar T, Acar N, Güngör F, Nuri Dilek O, Haciyanli M. Emergency laparoscopic colectomy for perforated diverticulitis - a video vignette. Colorectal Dis. 2018;20:736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Acar T, Acar N, Haciyanli M. Three-trocar colectomy for perforated diverticulitis - a video vignette. Colorectal Dis. 2019;21:729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bradley DR, Cutcomb S. Monte Carlo simulations and the chi-square test of independence. Behav Res Meth Instru. 1977;9:193-201. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lee KY, Lee J, Park YY, Kim Y, Oh ST. Difference in Clinical Features between Right- and Left-Sided Acute Colonic Diverticulitis. Sci Rep. 2020;10:3754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Soh NYT, Teo NZ, Tan CJH, Rajaraman S, Tsang M, Ong CJM, Wijaya R. Perforated diverticulitis: is the right and left difference present here too? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33:525-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hajibandeh S, Hajibandeh S, Smart NJ, Maw A. Meta-analysis of the demographic and prognostic significance of right-sided versus left-sided acute diverticulitis. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22:1908-1923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Laurell H, Hansson LE, Gunnarsson U. Acute diverticulitis--clinical presentation and differential diagnostics. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9:496-501; discussion 501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zuckerman J, Garfinkle R, Vasilevksy CA, Ghitulescu G, Faria J, Morin N, Boutros M. Short- and Long-Term Outcomes of Right-Sided Diverticulitis: Over 15 Years of North American Experience. World J Surg. 2020;44:1994-2001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tochigi T, Kosugi C, Shuto K, Mori M, Hirano A, Koda K. Management of complicated diverticulitis of the colon. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2018;2:22-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Aquina CT, Fleming FJ, Hall J, Hyman N. Do All Patients Require Resection After Successful Drainage of Diverticular Abscesses? J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;24:219-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Francis NK, Sylla P, Abou-Khalil M, Arolfo S, Berler D, Curtis NJ, Dolejs SC, Garfinkle R, Gorter-Stam M, Hashimoto DA, Hassinger TE, Molenaar CJL, Pucher PH, Schuermans V, Arezzo A, Agresta F, Antoniou SA, Arulampalam T, Boutros M, Bouvy N, Campbell K, Francone T, Haggerty SP, Hedrick TL, Stefanidis D, Truitt MS, Kelly J, Ket H, Dunkin BJ, Pietrabissa A. EAES and SAGES 2018 consensus conference on acute diverticulitis management: evidence-based recommendations for clinical practice. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:2726-2741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hall J, Hardiman K, Lee S, Lightner A, Stocchi L, Paquette IM, Steele SR, Feingold DL; Prepared on behalf of the Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Left-Sided Colonic Diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2020;63:728-747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 320] [Article Influence: 53.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lambrichts DPV, Bolkenstein HE, van der Does DCHE, Dieleman D, Crolla RMPH, Dekker JWT, van Duijvendijk P, Gerhards MF, Nienhuijs SW, Menon AG, de Graaf EJR, Consten ECJ, Draaisma WA, Broeders IAMJ, Bemelman WA, Lange JF. Multicentre study of non-surgical management of diverticulitis with abscess formation. Br J Surg. 2019;106:458-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Elagili F, Stocchi L, Ozuner G, Kiran RP. Antibiotics alone instead of percutaneous drainage as initial treatment of large diverticular abscess. Tech Coloproctol. 2015;19:97-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Vermeulen J, Coene PP, Van Hout NM, van der Harst E, Gosselink MP, Mannaerts GH, Weidema WF, Lange JF. Restoration of bowel continuity after surgery for acute perforated diverticulitis: should Hartmann's procedure be considered a one-stage procedure? Colorectal Dis. 2009;11:619-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ryan OK, Ryan ÉJ, Creavin B, Boland MR, Kelly ME, Winter DC. Systematic review and meta-analysis comparing primary resection and anastomosis versus Hartmann's procedure for the management of acute perforated diverticulitis with generalised peritonitis. Tech Coloproctol. 2020;24:527-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Oberkofler CE, Rickenbacher A, Raptis DA, Lehmann K, Villiger P, Buchli C, Grieder F, Gelpke H, Decurtins M, Tempia-Caliera AA, Demartines N, Hahnloser D, Clavien PA, Breitenstein S. A multicenter randomized clinical trial of primary anastomosis or Hartmann's procedure for perforated left colonic diverticulitis with purulent or fecal peritonitis. Ann Surg. 2012;256:819-26; discussion 826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bridoux V, Regimbeau JM, Ouaissi M, Mathonnet M, Mauvais F, Houivet E, Schwarz L, Mege D, Sielezneff I, Sabbagh C, Tuech JJ. Hartmann's Procedure or Primary Anastomosis for Generalized Peritonitis due to Perforated Diverticulitis: A Prospective Multicenter Randomized Trial (DIVERTI). J Am Coll Surg. 2017;225:798-805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Beyer-Berjot L, Maggiori L, Loiseau D, De Korwin JD, Bongiovanni JP, Lesprit P, Salles N, Rousset P, Lescot T, Henriot A, Lefrançois M, Cotte E, Parc Y. Emergency Surgery in Acute Diverticulitis: A Systematic Review. Dis Colon Rectum. 2020;63:397-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Rose J, Parina RP, Faiz O, Chang DC, Talamini MA. Long-term Outcomes After Initial Presentation of Diverticulitis. Ann Surg. 2015;262:1046-1053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Devaraj B, Liu W, Tatum J, Cologne K, Kaiser AM. Medically Treated Diverticular Abscess Associated With High Risk of Recurrence and Disease Complications. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59:208-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | El-Sayed C, Radley S, Mytton J, Evison F, Ward ST. Risk of Recurrent Disease and Surgery Following an Admission for Acute Diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61:382-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Suhardja TS, Norhadi S, Seah EZ, Rodgers-Wilson S. Is early colonoscopy after CT-diagnosed diverticulitis still necessary? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32:485-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Sharma PV, Eglinton T, Hider P, Frizelle F. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the role of routine colonic evaluation after radiologically confirmed acute diverticulitis. Ann Surg. 2014;259:263-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/