Published online Dec 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i12.111041

Revised: September 2, 2025

Accepted: October 17, 2025

Published online: December 27, 2025

Processing time: 149 Days and 0.7 Hours

The gut-vascular barrier (GVB) is critical for maintaining intestinal homeostasis, but its involvement in intestinal obstruction (IO) remains unclear.

To investigate GVB disruption in patients with IO and its association with perioperative infection, organ injury, and clinical prognosis.

Intestinal tissues from surgical patients with IO (IO group) and without obstruc

PV1 expression was significantly elevated in the IO group. In the IO group, PV1 levels were positively correlated with perioperative infection markers, liver and kidney injury indices, and adverse prognostic indicators, including prolonged hospitalization, antibiotic use, fever duration, and postoperative complications. Several of these outcomes were significantly worse in the PV1-high subgroup than in the PV1-low subgroup, although severe postoperative complications and mortality did not differ.

Our findings demonstrate that IO induces GVB damage, and the extent of impairment is closely associated with infection, organ injury, and adverse clinical outcomes in surgical patients, suggesting a pathogenic role for GVB disruption in IO.

Core Tip: This study reveals that intestinal obstruction (IO) leads to gut-vascular barrier (GVB) damage, with PV1 expression positively correlating with infection, liver/kidney injury, and adverse outcomes. GVB impairment may contribute to IO pathogenesis, highlighting PV1 as a potential prognostic biomarker.

- Citation: Zhang HF, Guo Y, Chen XJ, Zhang YN, Peng H, Liu ZM, Zhang XY. Associations of clinical indexes and prognosis with gut-vascular barrier damage in patients with intestinal obstruction. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(12): 111041

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i12/111041.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i12.111041

Intestinal obstruction (IO) is a common surgical emergency, predominantly caused by adhesions, neoplasms, and herniation. It occurs when mechanical factors impair, arrest, or revers the normal passage of intestinal contents factors[1]. IO frequently results in dysmotility, dysbiosis, ischemia, and infection[2]. Gut barrier dysfunction further exacerbates these complications and may progress to multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS)[3-5]. Reported mortality rates for small bowel and colon obstruction in the United States are approximately 10% and 30%, respectively[6]. Conse

The intestinal barrier comprises mechanical, chemical, immune, and biological components that maintain intestinal homeostasis[7-10]. In 2015, Spadoni et al[11] identified the gut-vascular barrier (GVB) in mice and humans, a structure similar to the blood-brain barrier. The GVB comprises vascular endothelial cells and intercellular junctional complexes, including adherens and tight junctions, and restricts the passage of macromolecules (> 70 kDa) from the intestinal tract to the bloodstream. When GVB is damaged, bacteria may translocate into the blood circulation, causing systemic infection and remote organ dysfunction. PV1 is a distinctive biomarker of GVB disruption, specifically expressed in the intestinal mucosal layer, and is widely used to assess the extent of barrier disruption[12-15]. Although several studies have focused on the intestinal epithelial barrier in IO, the role of GVB disruption and IO pathogenesis remains unclear.

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the impact of IO on GVB and analyze the correlation between GVB damage and perioperative infection, liver and kidney function, and clinical prognosis.

This controlled study was conducted at The First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University between March 1, 2021, and October 1, 2022. Patients who underwent gastroenteric surgery in the Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery were enrolled. Demographic and clinical data were collected upon admission. The inclusion criteria were as follows: Age 18-75 years, scheduled for intestinal excision surgery, and body mass index (BMI) of 18-28 kg/m2. Patients diagnosed with IO based on clinical and imaging criteria were enrolled in the IO group, whereas patients with tumor without IO served as controls. The exclusion criteria included severe hepatic or renal dysfunction, hematological disease, or a history of radiotherapy or chemotherapy. The Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University approved this study (No.[2021]810). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Tissue samples of the control group were collected from the proximal incisional margin, whereas those of the IO group were collected from regions proximal to the obstruction (Supplementary Figure 1). Each specimen was divided into two portions: One was stored at -80 °C for frozen sections, and the other was examined for reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis.

Total RNA was extracted from homogenized intestinal tissues using Trizol reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Complementary DNA was synthesized using the HiScript II Q RT SuperMix kit, following the manufacturer’s instructions, and PV1 mRNA expression was quantified using the LightCycler 480 SYBR Green Master Mix (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). The PV1 mRNA expression levels were normalized to that of β-actin. The primer sequences used for amplification were as follows: PV1: 5′-GCCAGGTGGTTGGACTATCTG-3′ and 5′-CTCCATCTCACGTCGCGTA-3′; β-actin: 5′-GTGACGTTGACATCCGTAAAGA-3′ and 5′-GCCGGACTCATCGTACTCC-3′. The relative mRNA expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method.

For immunofluorescence staining, intestinal tissues from ten patients per group were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 hours and embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound for frozen sectioning. Frozen sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-PV1 antibody (1:100, NB100-77668, Novus Biologicals, CO, United States) and anti-CD34 antibody (1:100, ab81289, Abcam, MA, United States). After incubation with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 hour, nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Images were acquired using a confocal laser scanning microscope, and fluorescence intensity was analyzed using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, United States). The PV1 nuclear/cytosolic ratio was determined by dividing the mean nuclear PV1 intensity by the mean cytoplasmic PV1 intensity.

Demographic and clinical data, including sex, age, BMI, heart rate, systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), pulse oxygen saturation (SPO2), medical history, and medication use, were extracted from admission records. Pre- and postoperative laboratory parameters, including procalcitonin (PCT), C-reactive protein (CRP), white blood cell (WBC) count, neutrophil (NEUT) count, lymphocyte (LY) percentage, LY count, neutrophilic granulocyte percentage, alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), alkaline phosphatase, cholinesterase (CHE), total bilirubin (TBIL), direct bilirubin (DBIL), indirect bilirubin (IBIL), creatinine (CREA), and blood urea nitrogen, were obtained from the hospital’s biochemical laboratory. These markers are well-established clinical indicators for monitoring infection and assessing liver and kidney function. Prognostic data, including total and postoperative hospitalization, duration of intravenous antibiotic use, duration of postoperative fever (temperature > 37 °C), postoperative complication rate (including skin incision infection, anastomotic fistula, abdominopelvic fluid, local intestinal torsion, pancreatitis, urinary tract infection, pneumonia, bacteremia, infectious shock, and MODS), and mortality rate, were also collected.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 25.0. Group comparisons of clinical variables and cytokines were conducted using Student’s t-test, χ2 test, or Mann-Whitney U test, as appropriate. Continuous variables are expressed as the median and interquartile range (IQR) or mean ± SD. Associations were analyzed using linear and logistic regression analyses. Binary logistic regression was used to identify the risk factors for postoperative complications and mortality. Statistical significance was set at two-sided P < 0.05.

A total of 167 patients scheduled for intestinal excision surgery were initially enrolled. After applying the exclusion criteria, 63 patients were excluded (Figure 1). Of the remaining patients, 55 controls and 49 patients with IO were eligible, but 13 and 7 patients, respectively, were excluded due to incomplete information and loss of postoperative follow-up. Finally, 84 patients were included, with 42 in each group. Table 1 shows that there were no statistically significant differences between the groups in age, sex, BMI, DBP, SBP, SPO2, or tissue collection sites. However, the IO group had a significantly higher preoperative heart rate. For infection indicators, patients with IO exhibited increased PCT, CRP, WBC, and NEUT levels, as well as decreased LY levels. For liver and renal functions, ALT, AST, LDH, and TBIL levels were higher in the IO group, whereas CHE level was lower. Additionally, a higher proportion of patients with IO underwent laparotomy due to urgent and complicated medical conditions.

| Variables | IO group (n = 42) | Control group (n = 42) | P value |

| Age (years) | 59.1 (45.5-72.7) | 58.7 (45.8-71.6) | 0.92 |

| Male, n (%) | 22 (52.3) | 19 (45.2) | 0.51 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.4 (18.6-24.2) | 22.3 (19.5-25.1) | 0.14 |

| HR (bpm) | 83.5 (81.8-91.5) | 77.0 (68.0-88.5) | 0.03 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 117.0 (111.0-125.5) | 125.5 (115.5- 133.5) | 0.09 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 76.0 (71.0-82.0) | 74.0 (69.8-80.3) | 0.06 |

| SPO2 (%) | 100 (100-100) | 100 (99-100) | 0.59 |

| ALT (U/L) | 13.5 (9.0-25.0) | 12.0 (9.0-17.3) | 0.01 |

| AST (U/L) | 21.5 (16.8-35.5) | 17.5 (15.0-20.2) | < 0.01 |

| LDH (U/L) | 208.5 (178.5-259.0) | 180.0 (156.0-202.5) | 0.02 |

| ALP (U/L) | 73.0 (55.5-89.0) | 79.0 (67.0-93.0) | 0.31 |

| CHE (U/L) | 5453.5 (3977.3-6092.0) | 6973.0 (6071.3-7705.3) | < 0.01 |

| TBIL (μmol/L) | 12.8 (7.9-17.0) | 9.8 (8.1-13.5) | 0.04 |

| DBIL (μmol/L) | 1.5 (0.0-3.0) | 1.6 (1.2-2.3) | 0.59 |

| IBIL (μmol/L) | 8.7 (5.4-11.7) | 8.0 (6.5-10.9) | 0.61 |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 4.3 (3.0-5.6) | 4.7 (3.5-5.8) | 0.82 |

| CREA (μmol/L) | 62.5 (48.7-90.5) | 67.5 (55.8-88.3) | 0.34 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 20.8 (8.0-58.3) | 3.2 (1.7-5.9) | < 0.01 |

| WBC (109/L) | 7.4 (5.9-9.3) | 6.1 (5.0-6.8) | < 0.01 |

| NEUT% | 0.7 (0.6-0.8) | 0.6 (0.5-0.7) | 0.27 |

| LY% | 0.2 (0.1-0.3) | 0.3 (0.2-0.4) | < 0.01 |

| NEUT (109/L) | 5.2 (3.5-6.8) | 3.6 (2.7-4.5) | < 0.01 |

| LY (109/L) | 1.3 (0.8-1.7) | 1.7 (1.4-2.1) | < 0.01 |

| Laparotomy, n (%) | 16 (38.1) | 3 (7.14) | 0.001 |

| Tissue sample: Colon, n (%) | 24 (57.1) | 28 (66.7) | 0.37 |

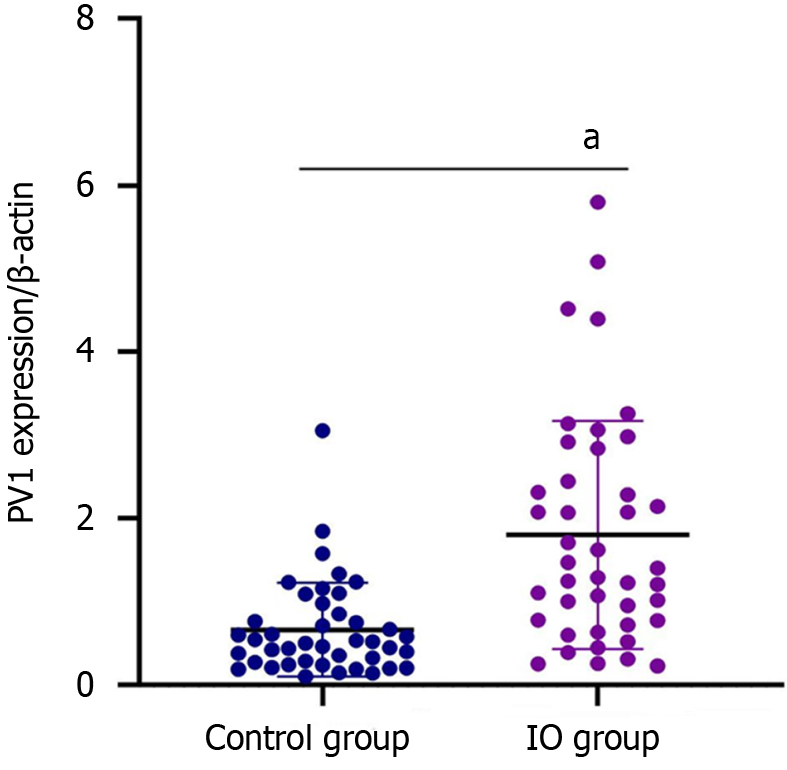

The PV1 expression levels were measured using RT-qPCR and immunofluorescence. PV1 mRNA and protein expression in intestinal mucosa were significantly higher in the IO group than in the control group (Figures 2 and 3).

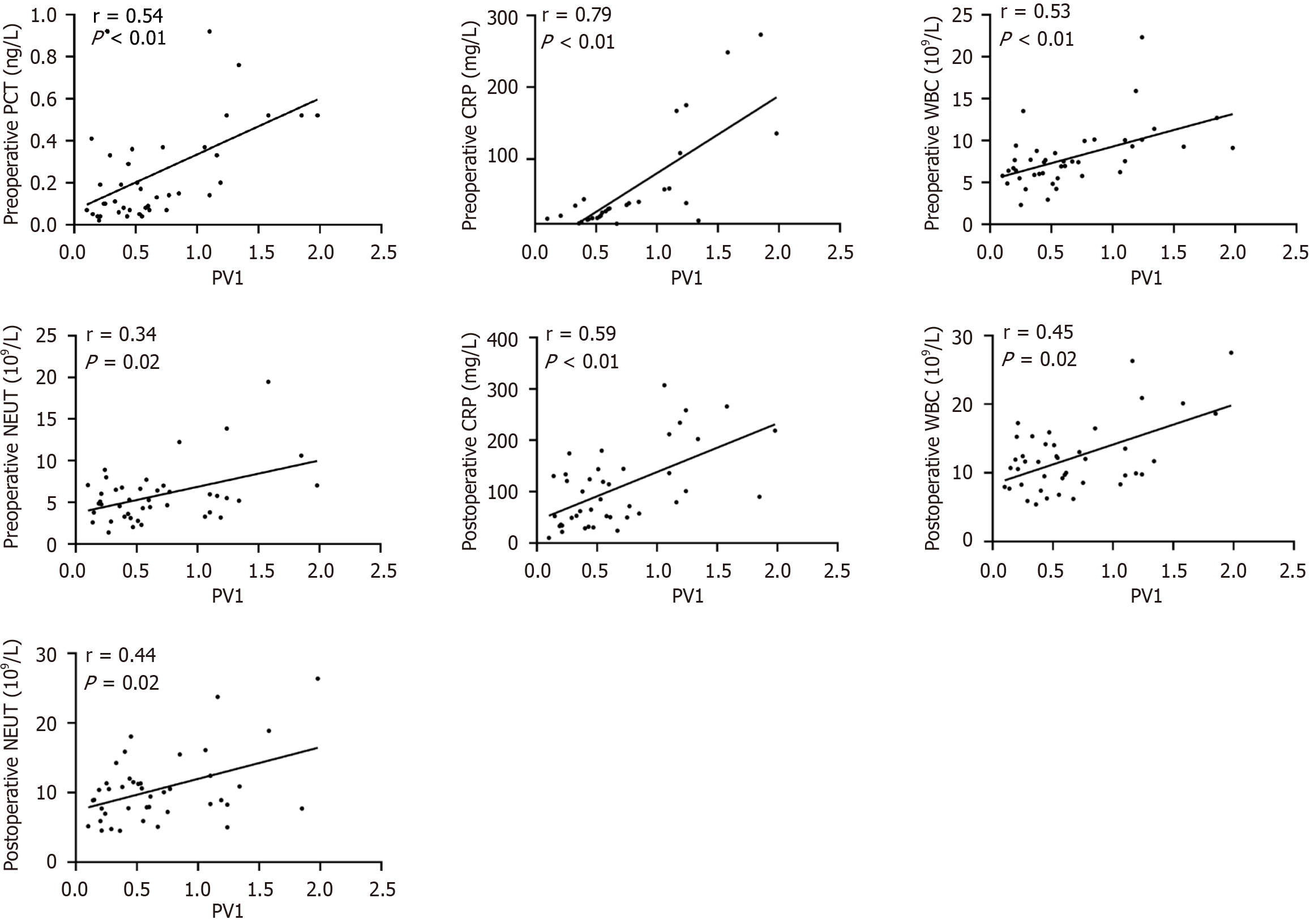

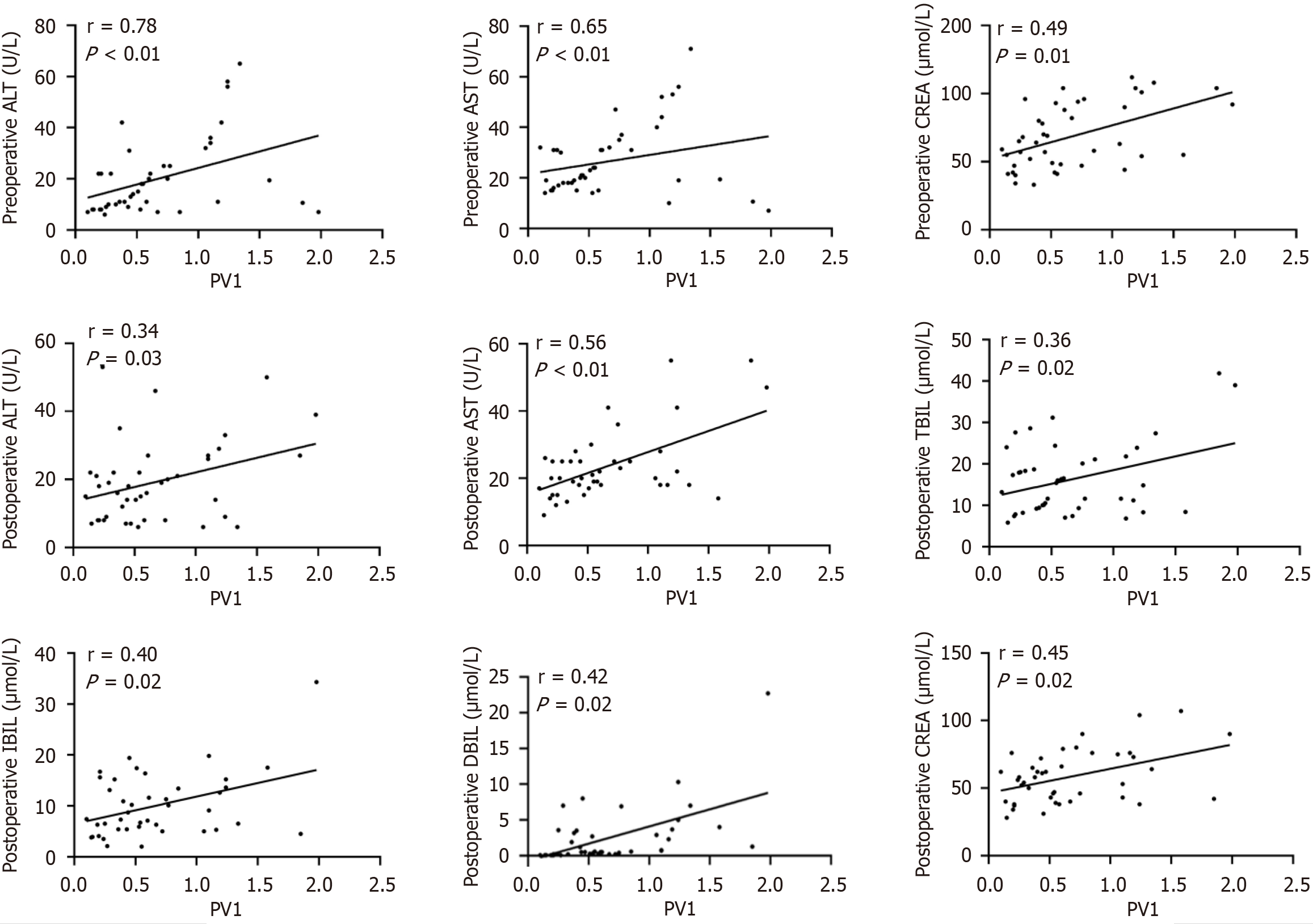

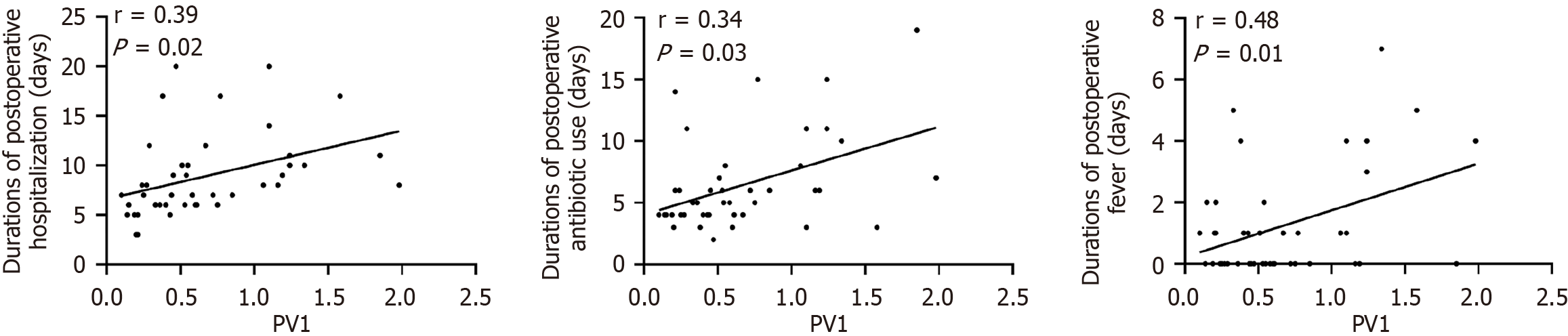

In the IO group, PV1 expression showed significant positive correlations with infection indicators (preoperative PCT, CRP, WBC, and NEUT; postoperative CRP, WBC, and NEUT; Figure 4 and Supplementary Table 1). For liver and kidney function, PV1 expression correlated positively with preoperative ALT, AST, and CREA, along with postoperative ALT, AST, TBIL, DBIL, IBIL, and CREA (Figure 5 and Supplementary Table 1). Moreover, among the prognostic indicators, PV1 expression levels in the IO group exhibited significant positive correlations with the durations of postoperative hospitalization, antibiotic use, and fever (Figure 6 and Supplementary Table 1). Furthermore, univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses revealed that elevated PV1 expression was associated with an increased risk of postoperative complications in patients with IO (Table 2).

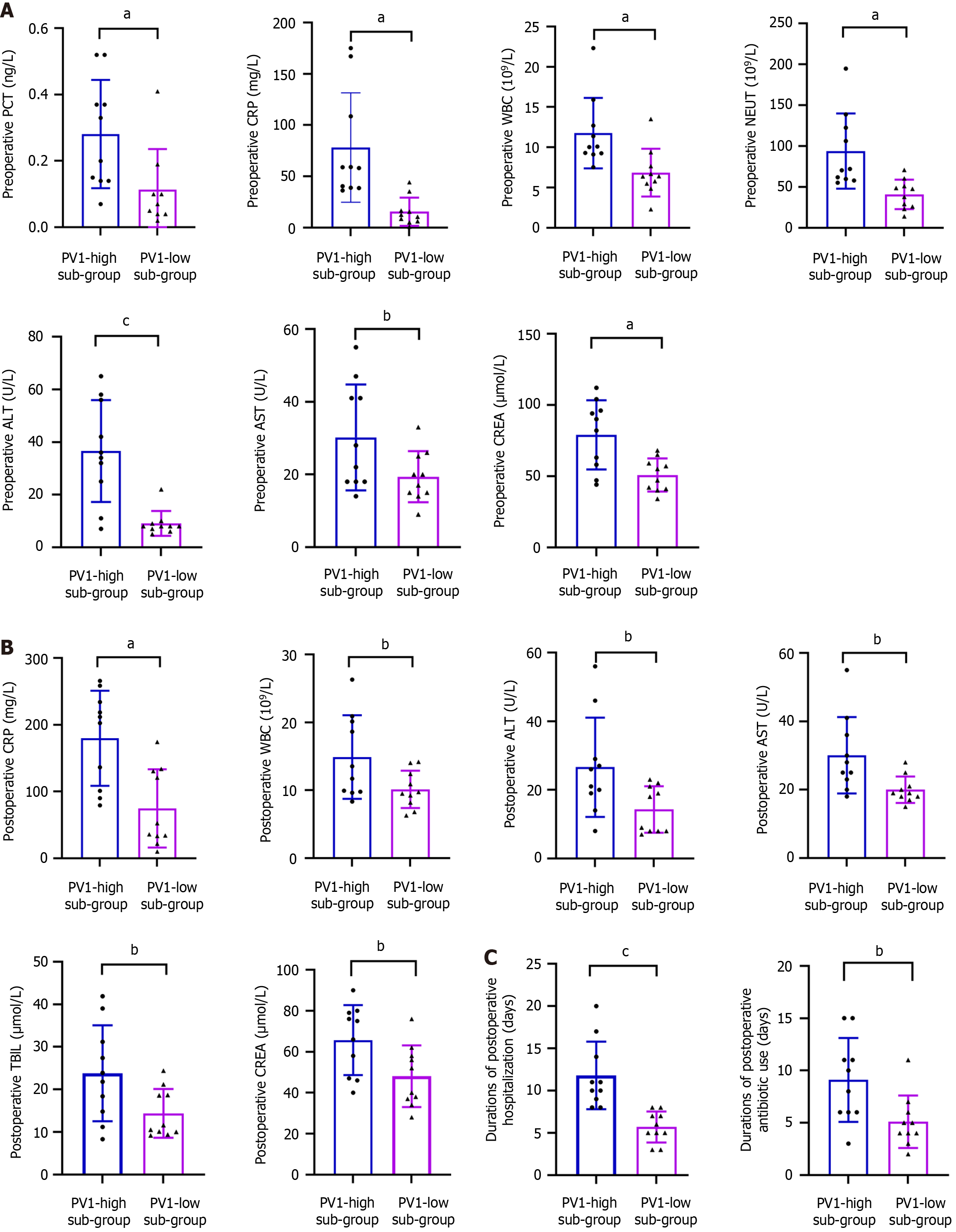

To further assess the association between PV1 expression and infection status, liver and kidney functions, and prognosis under IO condition, the IO group was divided into PV1-high (top 25%, 10 patients) and PV1-low (bottom 25%, 10 patients) subgroups based on PV1 mRNA levels. Compared with the PV1-low subgroup, the PV1-high subgroup showed significantly higher preoperative PCT, CRP, WBC, NEUT, ALT, AST, and CREA levels, as well as postoperative CRP, WBC, ALT, AST, TBIL, and CREA levels. They also exhibited prolonged postoperative hospitalization and antibiotic use (Figure 7 and Supplementary Figure 2). However, severe postoperative complications and mortality rates did not significantly differ between the two groups (Table 3).

| Variables | PV1-high sub-group (n = 10) | PV1-low sub-group (n = 10) | P value |

| Complications | 4 (40) | 0 (0) | 0.09 |

| Mortality | 2 (20) | 0 (0) | 0.47 |

The intestinal tract plays a pivotal role in the progression of critical diseases[3]. The GVB represents the final barrier against bacterial translocation, thereby limiting remote organ injury[16]. GVB disruption has been reported in patients with cirrhosis, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, alcoholic liver disease, and rheumatoid arthritis[17]. Moreover, our previous studies demonstrated that intestinal sepsis or ischemia-reperfusion injury led to GVB damage in mice[18,19]. The present study is the first to reveal that IO can induce GVB disruption (Figures 2 and 3), and that GVB impairment is closely associated with perioperative infection, organ injury, and adverse clinical outcomes in the surgical IO patients.

The liver receives approximately 80% of its blood supply from the intestine via the portal system[4,20]. Intestinal barrier dysfunction increases permeability, facilitating the entry of bacterial products and inflammatory mediators that promote liver injury[21-24]. The kidney, as the major organ for excreting water-soluble toxins, is also affected: When the intestinal barrier is compromised, dysbiosis and toxin absorption can impair renal function and predispose patients to acute or chronic nephropathy[25,26]. Several studies have highlighted the role of intestinal barrier disruption in hepatic and renal dysfunction. In the present study, liver and kidney function indicators were collected to examine the relationship between GVB damage and remote organ injury in patients with IO. Our correlation analyses revealed positive correlations between intestinal PV1 expression and liver enzymes, bilirubin, and CREA in the patients with IO (Figure 5), and pre- and postoperative liver enzymes and CREA were increased in the PV1-high subgroup (Figure 7A and B). Furthermore, PV1 expression had significant positive correlations with infection markers in the patients with IO (Figure 4). Collectively, these findings suggest that the severity of remote organ injury is positively correlated with GVB disruption, suggesting that GVB damage may be involved in IO deterioration during IO.

Surgical IO patients often present with poor health conditions and worse clinical outcomes. Thus, predicting individualized prognosis of these patients is very important[27]. In this study, we examined whether GVB damage was associated with adverse clinical prognosis in IO. The results demonstrated that elevated PV1 expression correlated with prolonged postoperative hospitalization, antibiotic use, and fever, as well as an increased risk of postoperative complications. Furthermore, four patients in the PV1-high subgroup experienced severe postoperative complications, including enterocutaneous fistula, abdominopelvic effusion, pneumonia, and bacteremia; two of them eventually died. In contrast, no patient in the PV1-low subgroup experienced postoperative complications (Table 3). These findings strongly suggest that GVB damage, as indicated by PV1 expression, may represent a promising biomarker for predicting clinical outcomes in surgical IO patients.

Several limitations exist in our study. First, all patients were recruited from a single hospital, resulting in a relatively small sample size. Therefore, future studies should prioritize larger, multicenter cohorts to strengthen generalizability. Second, due to ethical considerations, patients with intestinal cancer were used as the controls instead of healthy individuals. To minimize bias, however, we carefully screened patients and selected relatively healthy intestinal tissues for analysis. Third, this study was purely clinical, and mechanistic studies are required to elucidate the pathways underlying the contribution of GVB to IO. Finally, PV1 expression was measured only in intestinal tissues, which limits its clinical applicability. Therefore, future research should explore metabolomic or other minimally invasive approaches to identify reliable blood- or urine-based markers for assessing GVB injury and predicting clinical prognosis.

In summary, this study demonstrated that IO induces GVB disruption. Moreover, the degree of GVB injury was significantly associated with perioperative infection, liver and kidney injury, and adverse clinical outcomes in patients with IO. This suggests that GVB damage may represent a key pathogenic factor in IO pathogenesis.

| 1. | ten Broek RP, Issa Y, van Santbrink EJ, Bouvy ND, Kruitwagen RF, Jeekel J, Bakkum EA, Rovers MM, van Goor H. Burden of adhesions in abdominal and pelvic surgery: systematic review and met-analysis. BMJ. 2013;347:f5588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 309] [Cited by in RCA: 421] [Article Influence: 32.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jackson P, Vigiola Cruz M. Intestinal Obstruction: Evaluation and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2018;98:362-367. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Mittal R, Coopersmith CM. Redefining the gut as the motor of critical illness. Trends Mol Med. 2014;20:214-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 256] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sun J, Zhang J, Wang X, Ji F, Ronco C, Tian J, Yin Y. Gut-liver crosstalk in sepsis-induced liver injury. Crit Care. 2020;24:614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dominguez JA, Coopersmith CM. Can we protect the gut in critical illness? The role of growth factors and other novel approaches. Crit Care Clin. 2010;26:549-565, x. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Miller G, Boman J, Shrier I, Gordon PH. Etiology of small bowel obstruction. Am J Surg. 2000;180:33-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 282] [Cited by in RCA: 288] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Balmer ML, Slack E, de Gottardi A, Lawson MA, Hapfelmeier S, Miele L, Grieco A, Van Vlierberghe H, Fahrner R, Patuto N, Bernsmeier C, Ronchi F, Wyss M, Stroka D, Dickgreber N, Heim MH, McCoy KD, Macpherson AJ. The liver may act as a firewall mediating mutualism between the host and its gut commensal microbiota. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:237ra66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 374] [Cited by in RCA: 369] [Article Influence: 30.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wells JM, Brummer RJ, Derrien M, MacDonald TT, Troost F, Cani PD, Theodorou V, Dekker J, Méheust A, de Vos WM, Mercenier A, Nauta A, Garcia-Rodenas CL. Homeostasis of the gut barrier and potential biomarkers. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2017;312:G171-G193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 303] [Cited by in RCA: 446] [Article Influence: 49.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Brescia P, Rescigno M. The gut vascular barrier: a new player in the gut-liver-brain axis. Trends Mol Med. 2021;27:844-855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Liu S, Song P, Sun F, Ai S, Hu Q, Guan W, Wang M. The concept revolution of gut barrier: from epithelium to endothelium. Int Rev Immunol. 2021;40:401-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Spadoni I, Zagato E, Bertocchi A, Paolinelli R, Hot E, Di Sabatino A, Caprioli F, Bottiglieri L, Oldani A, Viale G, Penna G, Dejana E, Rescigno M. A gut-vascular barrier controls the systemic dissemination of bacteria. Science. 2015;350:830-834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 303] [Cited by in RCA: 547] [Article Influence: 49.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Liebner S, Corada M, Bangsow T, Babbage J, Taddei A, Czupalla CJ, Reis M, Felici A, Wolburg H, Fruttiger M, Taketo MM, von Melchner H, Plate KH, Gerhardt H, Dejana E. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling controls development of the blood-brain barrier. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:409-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 675] [Cited by in RCA: 658] [Article Influence: 36.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wang Y, Rattner A, Zhou Y, Williams J, Smallwood PM, Nathans J. Norrin/Frizzled4 signaling in retinal vascular development and blood brain barrier plasticity. Cell. 2012;151:1332-1344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 346] [Article Influence: 26.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Spadoni I, Fornasa G, Rescigno M. Organ-specific protection mediated by cooperation between vascular and epithelial barriers. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17:761-773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Rantakari P, Jäppinen N, Lokka E, Mokkala E, Gerke H, Peuhu E, Ivaska J, Elima K, Auvinen K, Salmi M. Fetal liver endothelium regulates the seeding of tissue-resident macrophages. Nature. 2016;538:392-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sorribas M, Jakob MO, Yilmaz B, Li H, Stutz D, Noser Y, de Gottardi A, Moghadamrad S, Hassan M, Albillos A, Francés R, Juanola O, Spadoni I, Rescigno M, Wiest R. FXR modulates the gut-vascular barrier by regulating the entry sites for bacterial translocation in experimental cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2019;71:1126-1140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 28.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Di Tommaso N, Santopaolo F, Gasbarrini A, Ponziani FR. The Gut-Vascular Barrier as a New Protagonist in Intestinal and Extraintestinal Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:1470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zhang YN, Chang ZN, Liu ZM, Wen SH, Zhan YQ, Lai HJ, Zhang HF, Guo Y, Zhang XY. Dexmedetomidine Alleviates Gut-Vascular Barrier Damage and Distant Hepatic Injury Following Intestinal Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury in Mice. Anesth Analg. 2022;134:419-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chang Z, Zhang Y, Lin M, Wen S, Lai H, Zhan Y, Zhu X, Huang Z, Zhang X, Liu Z. Improvement of gut-vascular barrier by terlipressin reduces bacterial translocation and remote organ injuries in gut-derived sepsis. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:1019109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Albillos A, de Gottardi A, Rescigno M. The gut-liver axis in liver disease: Pathophysiological basis for therapy. J Hepatol. 2020;72:558-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 542] [Cited by in RCA: 1467] [Article Influence: 244.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Nagata K, Suzuki H, Sakaguchi S. Common pathogenic mechanism in development progression of liver injury caused by non-alcoholic or alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Toxicol Sci. 2007;32:453-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Spencer MD, Hamp TJ, Reid RW, Fischer LM, Zeisel SH, Fodor AA. Association between composition of the human gastrointestinal microbiome and development of fatty liver with choline deficiency. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:976-986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 498] [Cited by in RCA: 552] [Article Influence: 36.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Tremaroli V, Bäckhed F. Functional interactions between the gut microbiota and host metabolism. Nature. 2012;489:242-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2779] [Cited by in RCA: 3177] [Article Influence: 226.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rahman K, Desai C, Iyer SS, Thorn NE, Kumar P, Liu Y, Smith T, Neish AS, Li H, Tan S, Wu P, Liu X, Yu Y, Farris AB, Nusrat A, Parkos CA, Anania FA. Loss of Junctional Adhesion Molecule A Promotes Severe Steatohepatitis in Mice on a Diet High in Saturated Fat, Fructose, and Cholesterol. Gastroenterology. 2016;151:733-746.e12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 268] [Article Influence: 26.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Andersen K, Kesper MS, Marschner JA, Konrad L, Ryu M, Kumar Vr S, Kulkarni OP, Mulay SR, Romoli S, Demleitner J, Schiller P, Dietrich A, Müller S, Gross O, Ruscheweyh HJ, Huson DH, Stecher B, Anders HJ. Intestinal Dysbiosis, Barrier Dysfunction, and Bacterial Translocation Account for CKD-Related Systemic Inflammation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:76-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hobby GP, Karaduta O, Dusio GF, Singh M, Zybailov BL, Arthur JM. Chronic kidney disease and the gut microbiome. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2019;316:F1211-F1217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 26.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hu WH, Cajas-Monson LC, Eisenstein S, Parry L, Cosman B, Ramamoorthy S. Preoperative malnutrition assessments as predictors of postoperative mortality and morbidity in colorectal cancer: an analysis of ACS-NSQIP. Nutr J. 2015;14:91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/