Published online Nov 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i11.110490

Revised: July 5, 2025

Accepted: September 11, 2025

Published online: November 27, 2025

Processing time: 171 Days and 11.6 Hours

Perforated gastric cancer (GC) is a rare but life-threatening surgical emergency. Optimal surgical management remains controversial, and evidence from high-volume centers, especially in Western countries, is limited.

To evaluate surgical and survival outcomes of patients with perforated GC (PGC) according to the initial treatment strategy.

A retrospective cohort study was conducted including all patients with pathologically confirmed perforated gastric adenocarcinoma treated at a single tertiary cancer center between January 2009 and March 2024. Surgical strategies were cate

Among 1586 GC patients undergoing surgical treatment, 36 (2.3%) presented with PGC. The mean age was 62.5 years, and 55% were male. American Society of An

When clinically feasible, gastrectomy—either immediate or delayed—provides superior survival compared to local perforation repair alone in patients with PGC.

Core Tip: This retrospective study evaluated the clinical characteristics and survival outcomes of patients with perforated gastric cancer (GC) according to the surgical treatment approach. We found that perforated GC (PGC) is a rare but severe complication of GC, associated with high hospital mortality. It occurred more frequently in patients with advanced-stage disease, particularly stages III and IV. Surgical management varied, including one-stage gastrectomy, primary perforation repair, or a two-stage strategy—initial closure followed by delayed gastrectomy. Among these, overall survival was significantly higher in patients who underwent gastrectomy. Therefore, when clinically feasible, gastrectomy—either immediate or staged—should be considered the preferred approach, as it confers a survival advantage over perforation repair alone in the context of PGC.

- Citation: Aguiar MFF, Pereira MA, Dias AR, Ribeiro Jr U, Ramos MFKP. Surgical treatment of perforated gastric tumors. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(11): 110490

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i11/110490.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i11.110490

Gastric cancer (GC) is the fifth most commonly diagnosed cancer worldwide, with an estimated 968350 new cases reported in 2022. It also ranks as the fifth leading cause of cancer-related mortality globally[1]. The high mortality rate is largely due to the asymptomatic nature of early-stage disease, leading to approximately one-third of patients being diagnosed at stage IV[2]. In this context, surgical intervention for stage IV GC is often indicated to manage symptoms and complications such as bleeding, perforation, and obstruction, typically with palliative intent[3].

Spontaneous perforation occurs in less than 5% of GC cases, representing a rare but severe complication, usually associated with advanced-stage disease and high mortality[4]. It is considered the second most common oncologic emergency after major upper gastrointestinal bleeding[5]. Preoperative diagnosis of GC in patients presenting with perforation is particularly challenging. These patients typically present with diffuse peritonitis, often misdiagnosed as complications of peptic ulcer disease, as only 10%-16% of gastric perforations are malignant in origin[6,7]. Even intraoperatively, distinguishing malignant from benign causes can be difficult, especially in the absence of intraoperative frozen section analysis or overt evidence of metastatic disease[6,8,9]. Consequently, a definitive diagnosis is often established only in the postoperative period.

Short-term outcomes in perforated GC (PGC) patients are frequently poor due to septic complications of peritonitis and high postoperative morbidity. Long-term outcomes are also limited by advanced tumor stage and the early onset of peritoneal metastasis following perforation[4].

The optimal surgical approach to PGC aims to achieve two primary goals: Control of sepsis and oncologically adequate resection[4]. This requires intraoperative diagnostic accuracy, disease staging, and adherence to oncologic principles[7,8]. Surgical strategies may include single-stage procedures—combining peritonitis management with immediate gas

Despite available strategies, the management of PGC remains complex, with no universally accepted standard of care, and the optimal surgical approach remains a matter of debate[4]. Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the surgical and survival outcomes of patients with PGC treated at a high-volume specialized cancer center, according to the primary treatment approach.

All patients with GC who underwent surgical procedures at our institution between January 2009 and March 2024 were retrospectively reviewed. The analysis included only patients with perforated gastric adenocarcinoma, confirmed histopathologically either preoperatively or intraoperatively. Patients with gastric perforation due to benign conditions (e.g., peptic ulcers), lymphoma, metastatic cancer, or gastrointestinal stromal tumors were excluded.

Clinical characteristics were collected from medical records and included sex, age, body mass index, Charlson-Deyo comorbidity index—excluding age and malignancy as comorbidities—and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification. Laboratory data included hemoglobin (g/dL), serum albumin (g/dL), and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio. Additional variables assessed included tumor location, histological subtype, TNM staging, and the type of surgical procedure performed.

Preoperative staging was based on abdominal and pelvic computed tomography, upper endoscopy, and laboratory evaluations. Tumor staging followed the 8th edition of the TNM classification system[10]. Surgical resections, total or subtotal gastrectomy with lymphadenectomy, were performed in accordance with the Japanese Gastric Cancer Asso

Postoperative complications (POC) were classified according to the Clavien-Dindo system[12], with Clavien III-V categorized as major complications. Additional surgical outcomes included surgical mortality (Clavien V), 30- and 90-day mortality, and length of hospital stay. Surgical approaches for PGC included: (1) One-stage surgery: Subtotal or total gas

The decision-making process was not standardized. Treatment was chosen on a case-by-case basis based on the patient's profile, tumor stage (resectability) and the surgeon's decision. In general, patients with poor overall general conditions, high clinical risk or advanced disease were reasons provided for local repair.

Postoperative follow-up was conducted quarterly during the first year and every six months thereafter. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee and registered online (www.plataformabrasil.com;

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software, version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Continuous variables were analyzed using the Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test, depending on the distribution of data.

Overall survival (OS) was analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method, with comparisons between groups performed using the log-rank test. OS was defined as the time (in months) from the date of definitive surgery to the date of death or last follow-up.

To identify independent predictors of OS, Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to calculate hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals. Variables found to be statistically significant in univariable analysis were included as covariates in the multivariable model. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

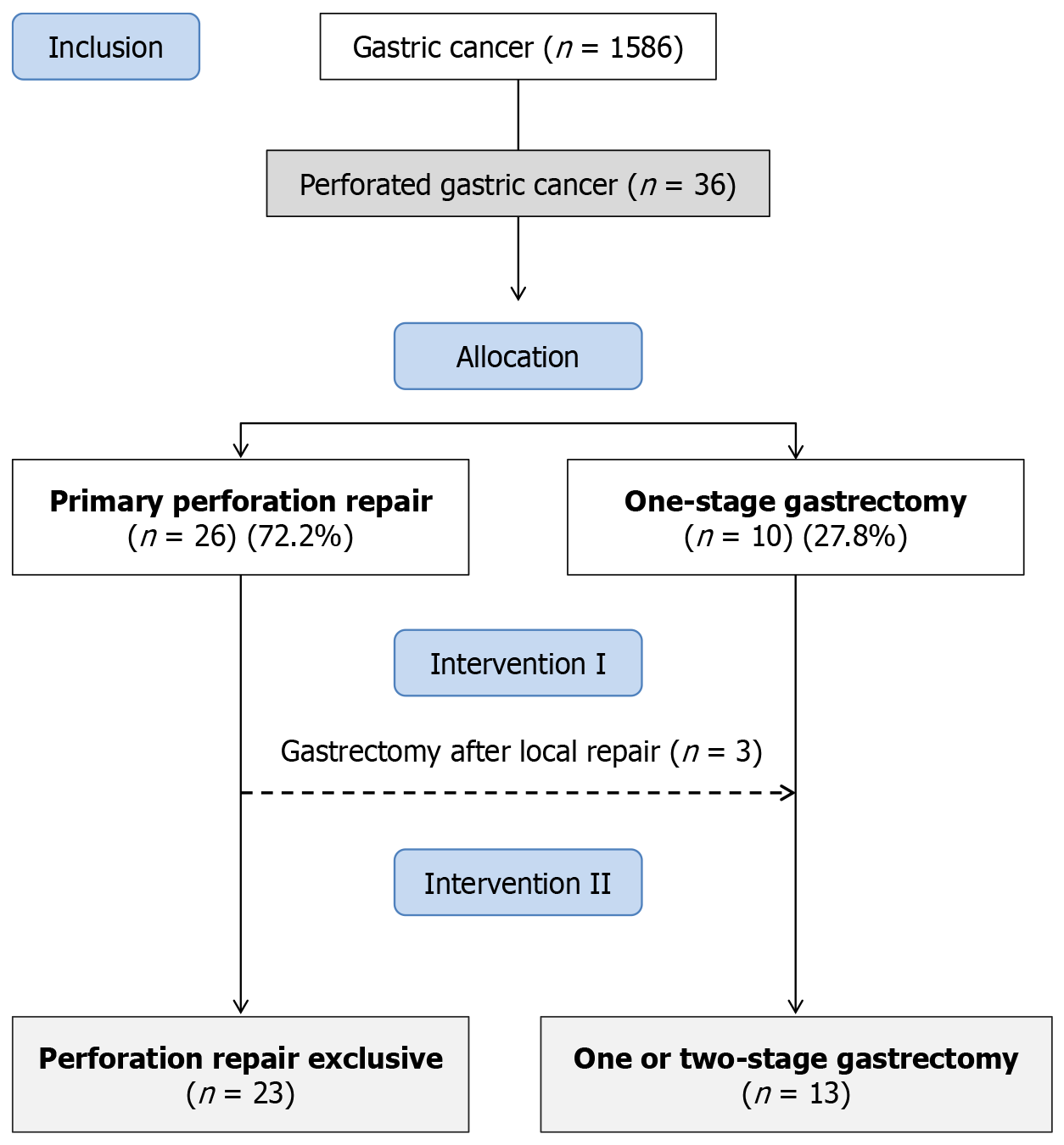

A total of 1586 patients with GC underwent surgical procedures at our institution between January 2009 and March 2024 (Figure 1). Among these, 36 patients (2.3%) were diagnosed with PGC and included in the study. The mean age was 62.5 years (SD: 12.9; range 38-84.9), and most patients were male (55.6%). ASA classification III/IV was observed in 58.3% of cases, and 33.3% had at least one comorbidity. The mean hemoglobin level was 10.4 g/dL (SD: 2.3), with anemia pre

According to the initial surgical approach (intervention I), 26 patients (72.2%) underwent primary perforation repair, while 10 patients (27.8%) underwent one-stage gastrectomy. Among the 26 patients initially treated with local repair, 3 (11.5%) were later deemed eligible for definitive surgical resection and underwent gastrectomy in a two-stage approach, with a mean interval of 4.4 months between procedures. Thus, considering the final treatment (intervention II), 23 pa

Clinical characteristics stratified by initial treatment (intervention I) are shown in Table 1. No significant differences were observed in age, sex, laboratory parameters, or comorbidities. ASA class III/IV was more frequent in the Perforation Repair Group, although not statistically significant (P = 0.260). Diffuse-type tumors and poorly differentiated histology were significantly more common in the Perforation Repair Group (P = 0.024 and P = 0.014, respectively). There were no significant differences in cT or cN stage between groups. Distant metastases were more frequent in the Perforation Repair Group (57.7% vs 30%), though this difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.137; Table 2).

| Variables | Primary perforation repair, n = 26 | One-stage gastrectomy, n = 10 | P value |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.722 | ||

| Female | 11 (42.3) | 5 (50) | |

| Male | 15 (57.7) | 5 (50) | |

| Age (years) | 61 ± 13.4 | 66.5 ± 11.3 | 0.263 |

| Body mass index (kg/m²) | 21.1 ± 4.6 | 23.5 ± 3.0 | 0.145 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.5 ± 2.3 | 10.2 ± 2.4 | 0.736 |

| < 11, n (%) | 17 (65.4) | 7 (70) | 1.0 |

| Albumin (g/dL), n (%) | 3.0 (0.9) | 3.2 (0.7) | 0.492 |

| < 3.5 | 16 (61.5) | 6 (60) | 1.000 |

| Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio | 1.92 ± 1.15 | 2.56 ± 1.16 | 0.145 |

| Charlson-Deyo comorbidity index, n (%) | 0.688 | ||

| 0 | 19 (73.1) | 6 (60) | |

| ≥ 1 | 7 (26.9) | 4 (40) | |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists, n (%) | 0.260 | ||

| I/II | 9 (34.6) | 6 (60) | |

| III/IV | 17 (65.4) | 4 (40) | |

| Tumor location, n (%) | 0.709 | ||

| Distal third | 9 (34.6) | 5 (50) | |

| Middle third | 4 (15.4) | 1 (10) | |

| Proximal third | 9 (34.6) | 4 (40) | |

| Linite plastica | 4 (15.4) | 0 (0) | |

| Lauren type, n (%) | 0.024 | ||

| Intestinal | 12 (46.2) | 9 (90) | |

| Diffuse/mixed | 14 (53.8) | 1 (10) | |

| Histological tumor grade, n (%) | 0.014 | ||

| Well/moderately differentiated | 4 (15.4) | 6 (60) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 22 (84.6) | 4 (40) |

| Variables | Primary perforation repair, n = 26 | One-stage gastrectomy, n = 10 | P value |

| cT | 1.0 | ||

| < T4a | 14 (53.8) | 5 (50) | |

| cT4b | 12 (46.2) | 5 (50) | |

| cN | 0.484 | ||

| cN0 | 1 (3.8) | 1 (10) | |

| cN+ | 5 (96.2) | 9 (90) | |

| cM | 0.137 | ||

| cM0 | 11 (42.3) | 7 (70) | |

| cM1 | 15 (57.7) | 3 (30) | |

| cTNM | 0.324 | ||

| ≤ III | 4 (15.4) | 2 (20) | |

| IVA | 7 (26.9) | 5 (50) | |

| IVB | 15 (57.7) | 3 (30) | |

| Preoperative chemotherapy | 0.397 | ||

| No | 19 (73.1) | 9 (90) | |

| Yes | 7 (26.9) | 1 (10) | |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 0.185 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 11 (5-20) | 13.5 (10-37) | |

| Postoperative complication (Clavien-Dindo) | 1.000 | ||

| 0-I-II | 9 (34.6) | 3 (30) | |

| III-V | 18 (69.2) | 7 (70) | |

| Clavien V | 0.260 | ||

| No | 9 (35.6) | 6 (60) | |

| Yes | 17 (65.4) | 4 (40) | |

| Mortality | |||

| 30-day | 16 (61.5) | 3 (30) | 0.139 |

| 90-day | 17 (65.4) | 3 (30) | 0.073 |

Postoperative outcomes showed no significant differences in length of hospital stay or incidence of major complications between groups. Thirty- and 90-day mortality rates were higher in the Perforation Repair Group than in the Gastrectomy Group, but these differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.139 and P = 0.073, respectively; Table 2).

Among the 13 patients who underwent gastrectomy, 10 (76.9%) underwent curative-intent resection, while 3 (23.1%) received palliative gastrectomy. Regarding surgical strategy, 10 (76.9%) patients underwent one-stage gastrectomy at the time of perforation, and 3 (23.1%) underwent a two-stage approach.

Of the 13 gastrectomies performed, 8 (61.5%) were total gastrectomies. D2 Lymphadenectomy was carried out in 5 pa

| Variables | Gastrectomy, n = 13 | % |

| Previous perforation repair | ||

| Yes | 3 | 23.1 |

| Lymphadenectomy | ||

| D0/D1 | 8 | 61.5 |

| D2 | 5 | 38.5 |

| Type of gastrectomy | ||

| Subtotal | 5 | 38.5 |

| Total | 8 | 61.5 |

| Tumor size (cm) | 5.8 ± 3.7 | |

| Invasion | ||

| Lymphatic invasion | 8 | 61.5 |

| Venous invasion | 8 | 61.5 |

| Perineural invasion | 6 | 46.2 |

| pT | ||

| pT2 | 1 | 7.7 |

| pT3 | 2 | 15.4 |

| pT4 | 10 | 76.9 |

| Number of dissected LN | 23.1 ± 16.7 | |

| pN | ||

| pN0 | 5 | 38.5 |

| pN+ | 8 | 61.5 |

| pM | ||

| pM0 | 10 | 76.9 |

| pM1 | 3 | 23.1 |

| pTNM | ||

| > II | 1 | 15.4 |

| III | 8 | 61.5 |

| IV | 3 | 23.1 |

| No | Sex | Age (year) | cTNM | Clavien (local repair) | Interval local repair vs gastrectomy (month) | Type of surgery | pTNM | DFS (month) | OS (month) | Status |

| 1 | Male | 68.9 | T4b N1 M0 | 4 | 6.4 | TG D2 | pT4 pN0 pM0 | 14 | 21.6 | Death |

| 2 | Male | 68.5 | T4b N1 M0 | 2 | 3.4 | TG D2 | pT4 pN1 pM0 | 11.6 | 20.5 | Death |

| 3 | Male | 39.1 | T1 N1 M0 | 2 | 3.5 | SG D2 | pT3 pN1 pM0 | 53.3 | 53.3 | Alive |

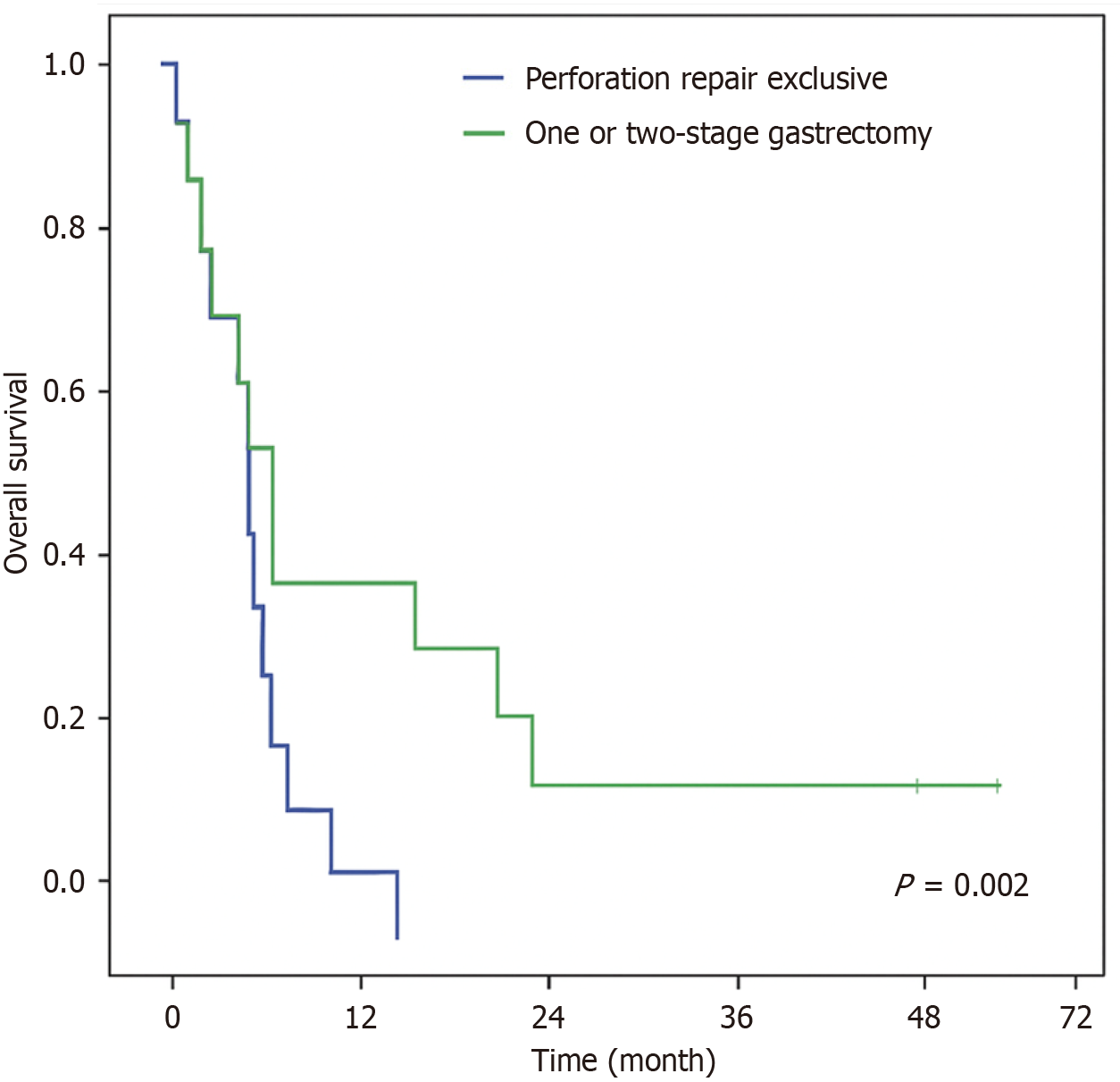

Survival analysis was conducted based on the final treatment received by patients with PGC (Intervention II). During follow-up, 32 patients (88.9%) died—22 in the Perforation Repair Group and 10 in the Gastrectomy Group. The median OS for the entire cohort was 0.7 months. Among the survivors, the median follow-up time was 33 months.

When stratified by treatment modality, patients who underwent gastrectomy demonstrated significantly improved survival compared to those who received perforation repair alone (P = 0.002). The median OS was 0.5 months in the Perforation Repair Group and 8.8 months in the Gastrectomy Group (Figure 2). On multivariable analysis (Table 5), gastrectomy emerged as the only independent factor significantly associated with improved survival (P = 0.026).

| Overall survival, variables | Univariable | Multivariable | ||||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Female (vs male) | 1.47 | 0.70-3.07 | 0.306 | - | - | - |

| Age > 65 years (vs < 65 years) | 0.69 | 0.34-1.40 | 0.306 | - | - | - |

| Charlson > 1 (vs CCI 0) | 1.25 | 0.59-2.66 | 0.557 | - | - | - |

| ASA III/IV (vs ASA I/II) | 1.79 | 0.87-3.68 | 0.114 | - | - | - |

| Hemoglobin < 11 g/dL (vs > 11 g/dL) | 2.41 | 1.05-5.52 | 0.037 | 1.56 | 0.45-5.40 | 0.478 |

| Albumin < 3.5 g/dL (vs > 3.5 g/dL) | 2.35 | 1.09-5.07 | 0.029 | 1.44 | 0.42-4.91 | 0.561 |

| cM1 (vs cM0) | 3.25 | 1.41-7.52 | 0.006 | 1.43 | 0.50-4.09 | 0.509 |

| Perforation repair exclusive (vs gastrectomy) | 3.66 | 1.51-8.87 | 0.004 | 3.18 | 1.15-8.82 | 0.026 |

PGC constitutes a rare but severe oncologic emergency, representing a small fraction of GC presentations yet carrying a disproportionately poor prognosis and high perioperative mortality, particularly in patients with advanced disease. Sur

Generally, patients who undergo primary perforation repair tend to have worse clinical characteristics. In our study, however, although these patients had a higher frequency of ASA III/IV and incidence of metastatic disease (cM1 in 57.7%), the difference was not significant. Patients in primary perforation repair had only a predominance of more aggressive tumor biology—characterized by a higher prevalence of diffuse-type histology and poorly differentiated tumors. Even though there was no statistically significant difference in all aspects, these factors likely influenced the decision toward damage-control surgery and may have contributed to the higher postoperative morbidity and mortality still observed in this group.

In contrast, patients selected for gastrectomy—either as a one-stage or two-stage approach—generally exhibited a more favorable clinical profile, with better performance status and lower disease burden, which likely enabled more definitive oncologic intervention. This translated into significantly improved OS, underscoring the potential benefit of resection in carefully selected patients.

In fact, the decision-making process between choosing one procedure over another could not be standardized. In certain cases, such as with unresectable tumors, suturing was the only viable option. However, in other situations, both procedures were feasible, and the choice was left to the surgeon’s discretion. Although the patient's instability during the procedure is an important factor influencing this decision, this information was not consistently documented in the re

In our institution, the incidence of perforation among patients with GC was 2.3%, aligning with previously reported rates in the literature[5,7,8,13]. Consistent with other studies, patients with PGC were typically older than those with perforated peptic ulcer disease, which more commonly affects younger individuals[6,14]. In our cohort, the mean age was 62.5 years, and 55.6% of patients were male, figures in line with demographic patterns reported in earlier studies.

As observed in other series, the majority of our patients were managed with primary perforation repair rather than immediate gastrectomy. This approach is often necessitated by the poor clinical status and frailty of patients presenting with PGC, coupled with extensive peritoneal contamination, which makes curative resection with lymphadenectomy technically demanding. Tumor stage also plays a decisive role in guiding surgical strategy: Most patients present with unresectable or metastatic disease at the time of perforation. In our study, 91.7% of patients had advanced-stage disease (stage III or IV), and 50% had distant metastases (cM1). As a result, the overall resection rate was limited to 36.1%. These findings are consistent with previous reports, such as the study by Kandel et al[15] ,which documented a resection rate of 27.2% (6/22), while an higher rates were found in the studies by Kim et al[16] (45.7%; 16/35), Roviello et al[6] (60%; 6/10), and Hata et al[7] (76.9%; 388/504).

The role of a two-stage surgical strategy—proposed as a potential compromise between immediate gastrectomy and simple perforation repair—was limited in our series. Among the 26 patients initially managed with perforation repair, only three (11.5%) ultimately underwent delayed gastrectomy after clinical stabilization, highlighting the advanced dis

Importantly, this study underscores the challenges of PGC in patients with limited clinical and surgical fitness. Standard surgery involving gastrectomy with D2 Lymphadenectomy is often not feasible in this context. In our series, only 38.5% of resected patients underwent a standard D2 lymphadenectomy, and the mean number of lymph nodes retrieved across all gastrectomies (23.1 ± 15.9) was below the institutional average for elective cases, which aligns with the JGCA recommendation of retrieving at least 25 lymph nodes[11]. These findings are consistent with those reported by Jwo et al[9], who demonstrated that lymphadenectomy in PGC is frequently limited due to technical challenges and the unstable condition of patients.

A key finding of our study is the markedly poorer short-term outcomes and OS in patients undergoing local repair compared to those receiving gastrectomy. Although not statistically significant, 30- and 90-day mortality rates were approximately twice as high in the local repair group. Moreover, the median OS was significantly lower in patients treated with local repair alone vs those who underwent gastrectomy (0.5 months vs 8.8 months; P = 0.002). These results are consistent with Kim et al[16], who reported improved outcomes among patients undergoing resection (45.7% resection rate; 30-day mortality 25.0%) compared to local repair[10]. Similarly, Hata et al[7] observed a 76.9% resection rate and found that one-stage gastrectomy was associated with lower postoperative mortality and better long-term survival. Collectively, these findings suggest that surgical resection, even in urgent settings, may provide survival benefits over conservative repair approaches in selected patients[7,16,17].

However, this survival difference should be interpreted with caution, as patient characteristics likely influenced the decision to forgo resection and contributed to the poorer prognosis. To address this potential bias, we performed mul

This study has several limitations. First, the small patient cohort limits the scope of certain analyses, potentially increasing the risk of type II errors. Given the low incidence of PGC, the results should be interpreted with caution, and the significance threshold of P < 0.05 should be considered flexibly. Additionally, comparing prognosis between groups may be confounded by the fact that patients who did not undergo resection generally had more advanced tumors that were unresectable due to their extent.

Another limitation is the incomplete data on patients with stage IV disease managed exclusively by the oncology department, which prevented analysis of the incidence of perforation occurring during palliative treatment. This limits our ability to identify and characterize potential risk factors for perforation during therapy, a gap that, if addressed, would improve understanding of this complication. Furthermore, since some gastrectomies were performed with pal

Nevertheless, our study has important strengths, including the consistency of surgical decision-making and technique, as all procedures were performed or supervised by the same experienced surgical team. The integration of emergency and elective surgeries within a single service minimized referral bias and loss to follow-up. Comprehensive data col

In summary, treatment decisions for PGC should carefully balance oncologic and emergency criteria on a case-by-case basis. For patients with resectable, technically feasible tumors, localized peritonitis, good performance status, and clinical stability, one-stage radical gastrectomy with lymphadenectomy may be appropriate. Palliative surgery is indicated for those with advanced disease. When resection is technically possible but clinical status is poor, a two-stage surgical app

PGC carries had a dismal prognosis, often affecting patients with poor clinical status and advanced disease. POC rates are high regardless of the surgical approach, and mortality remains substantial. However, when feasible, gastrectomy should be performed, as it offers significantly better survival outcomes compared to local repair alone.

| 1. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 68832] [Article Influence: 13766.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (202)] |

| 2. | Ramos MFKP, Pereira MA, Yagi OK, Dias AR, Charruf AZ, Oliveira RJ, Zaidan EP, Zilberstein B, Ribeiro-Júnior U, Cecconello I. Surgical treatment of gastric cancer: a 10-year experience in a high-volume university hospital. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2018;73:e543s. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ramos MFKP, Pereira MA, Dias AR, Castria TB, Sakamoto E, Ribeiro-Jr U, Zilberstein B, Nahas SC. SURGICAL TREATMENT IN CLINICAL STAGE IV GASTRIC CANCER: A COMPARISON OF DIFFERENT PROCEDURES AND SURVIVAL OUTCOMES. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2022;35:e1648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Di Carlo S, Franceschilli M, Rossi P, Cavallaro G, Cardi M, Vinci D, Sibio S. Perforated gastric cancer: a critical appraisal. Discov Oncol. 2021;12:15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Vasas P, Wiggins T, Chaudry A, Bryant C, Hughes FS. Emergency presentation of the gastric cancer; prognosis and implications for service planning. World J Emerg Surg. 2012;7:31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Roviello F, Rossi S, Marrelli D, De Manzoni G, Pedrazzani C, Morgagni P, Corso G, Pinto E. Perforated gastric carcinoma: a report of 10 cases and review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2006;4:19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hata T, Sakata N, Kudoh K, Shibata C, Unno M. The best surgical approach for perforated gastric cancer: one-stage vs. two-stage gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer. 2014;17:578-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lehnert T, Buhl K, Dueck M, Hinz U, Herfarth C. Two-stage radical gastrectomy for perforated gastric cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2000;26:780-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jwo SC, Chien RN, Chao TC, Chen HY, Lin CY. Clinicopathological features, surgical management, and disease outcome of perforated gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2005;91:219-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, Compton CC, Gershenwald JE, Brookland RK, Meyer L, Gress DM, Byrd DR, Winchester DP. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more "personalized" approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:93-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2341] [Cited by in RCA: 4711] [Article Influence: 523.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 11. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2018 (5th edition). Gastric Cancer. 2021;24:1-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 735] [Cited by in RCA: 1419] [Article Influence: 283.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 12. | Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18532] [Cited by in RCA: 26216] [Article Influence: 1191.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | Mahar AL, Brar SS, Coburn NG, Law C, Helyer LK. Surgical management of gastric perforation in the setting of gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2012;15 Suppl 1:S146-S152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kasakura Y, Ajani JA, Mochizuki F, Morishita Y, Fujii M, Takayama T. Outcomes after emergency surgery for gastric perforation or severe bleeding in patients with gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2002;80:181-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kandel BP, Singh Y, Singh KP, Khakurel M. Gastric cancer perforation: experience from a tertiary care hospital. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2013;52:489-493. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Kim BS, Oh ST, Yook JH, Kim BS. What is the appropriate management for perforated gastric cancer? Am Surg. 2014;80:517-520. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Melloni M, Bernardi D, Asti E, Bonavina L. Perforated Gastric Cancer: A Systematic Review. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2020;30:156-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/