Published online Oct 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i10.111558

Revised: July 15, 2025

Accepted: August 26, 2025

Published online: October 27, 2025

Processing time: 113 Days and 17.6 Hours

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are the most common mesenchymal tumors of the gastrointestinal tract and arise from the interstitial cells of Cajal. They predominantly affect individuals between 50 and 70 years of age and often carry malignant potential despite being frequently asymptomatic. The stomach and small intestine are the most common locations, while involvement of the eso

Core Tip: Endoscopic resection has emerged as a promising, minimally invasive treatment for gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs). Techniques like endoscopic submucosal dissection, submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection, and endoscopic full-thickness resection have shown favorable outcomes, including high rates of complete tumor removal, reduced recovery times, and preservation of gastric function. This review explores the advancements in these techniques, highlighting their safety, efficacy, and the growing role of endoscopy in GIST management. Key factors for selecting the appropriate resection method depend on tumor size, location, and patient-specific factors.

- Citation: Wu J, Jin ZD. Advancements in endoscopic resection of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: Techniques, outcomes, and perspectives. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(10): 111558

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i10/111558.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i10.111558

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are the most common mesenchymal neoplasms of the gastrointestinal tract, representing approximately 1% of all primary malignant gastrointestinal tumors. These tumors originate from the interstitial cells of Cajal and are typically driven by activating mutations in the KIT or PDGFRA genes. The global incidence of GISTs is estimated to be between 7 and 15 cases per million annually, with an increasing trend attributed to heightened awareness and improvements in diagnostic modalities[1,2]. In the United States, approximately 5000 to 6000 new cases are diagnosed each year[3].

GISTs most frequently arise in the stomach (60%-70%) and small intestine (20%-30%), though they can develop anywhere along the gastrointestinal tract, including the esophagus, colon, and rectum[4]. Small or early-stage tumors are often asymptomatic because they tend to grow slowly and do not commonly ulcerate or obstruct the gastrointestinal lumen. As a result, patients rarely present with symptoms until the tumor reaches a significant size or causes bleeding. Therefore, many GISTs are discovered incidentally during imaging or endoscopic procedures conducted for other clinical indications[5].

Conventional endoscopy alone yields a limited diagnostic accuracy for subepithelial lesions such as GISTs. In contrast, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) offers high-resolution imaging that allows for characterization of lesion size, origin layer, echotexture, and vascular pattern, thus enhancing diagnostic confidence[6,7]. Beyond determining tumor size and location, EUS plays a pivotal role in selecting the appropriate resection technique. Evaluation of the tumor’s layer of origin (typically the muscularis propria for GISTs) helps determine whether endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), endoscopic submucosal excavation (ESE), submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection (STER), or endoscopic full-thickness resection (EFTR) is most suitable. Intramural or endoluminal growth patterns are generally amenable to ESD or STER, while tumors with exophytic extension or broad serosal contact may necessitate EFTR. Echogenicity and internal characteristics-such as heterogeneity, cystic components, or irregular margins can suggest a higher risk of malignancy and warrant more aggressive intervention. Proximity to vital structures such as major vessels or the esophagogastric junction influences the technical complexity and risk, often favoring techniques with controlled dissection planes like STER or laparoscopic assistance. High-risk EUS features-including ulceration, irregular borders, or heterogeneous echotexture-are critical not only in guiding the decision to resect but also in anticipating procedural challenges[8].

Traditionally, surgical resection has been the mainstay of treatment for localized GISTs, with laparoscopic approaches being favored for tumors less than 5 cm in size. However, surgical resection may pose challenges in anatomically complex regions such as the gastric cardia, fundus, or pylorus, and is often associated with more extensive gastric manipulation[9,10]. Over the past decade, therapeutic endoscopy has undergone rapid development, and endoscopic resection is now recognized as a viable alternative to surgery for selected nonmetastatic GISTs.

Endoscopic techniques offer several advantages over surgery, including real-time tumor localization, reduced blood loss, lower procedural morbidity, shorter hospital stay, and preservation of gastric anatomy and function[11]. The most commonly used endoscopic resection methods include ESD, ESE, STER, and EFTR. These techniques have demonstrated favorable safety and efficacy profiles, particularly for intramural tumors smaller than 5 cm in expert hands[12-15].

In this review, we summarize recent advancements in endoscopic resection of GISTs, with a focus on current evidence regarding safety, feasibility, clinical outcomes, and selection criteria for each technique. We also discuss procedural challenges, complication management, and the evolving role of EUS in diagnosis, surveillance, and treatment planning.

The management of GISTs is influenced by factors such as tumor size, location, risk assessment, and individual patient characteristics. The two primary management strategies are active surveillance and resection.

According to current guidelines, asymptomatic GISTs smaller than 2 cm without high-risk features on EUS such as irregular borders, ulceration, or heterogeneous echotexture, and can be managed with active surveillance using periodic EUS evaluations[16]. Active surveillance is particularly appropriate for elderly patients, those with significant co

In this review, we will explore the four major endoscopic techniques for GIST resection. These techniques are ESD, ESE, STER, and EFTR (Table 1).

| Technique | Indications | Contraindications | Key advantages | Common complications | Technical complexity | Typical complete resection rate |

| ESD | Small, intraluminal GISTs ≤ 2-3 cm confined to mucosa/submucosa; favorable gastric locations | Deep muscularis invasion; poor lifting sign; proximity to large vessels | En bloc resection; tissue preservation | Bleeding (up to 15%), perforation (1%-8%) | High | Approximately 90%-95% |

| ESE | Intramural GISTs with muscularis propria origin; gastric cardia | Large extraluminal tumors; thin gastric walls | Deeper dissection capability | Bleeding (5%-18%), perforation (2%-10%) | Very high | Approximately 90%-95% |

| STER | Intramural tumors in esophagus or gastric cardia; | Poor tunneling route; exophytic growth | Mucosal preservation; low leakage risk | Gas-related events (2%-6%), submucosal abscess | Very high | > 95% |

| EFTR | Deeply embedded or exophytic tumors; non-lifting lesions; tumors > 3-4 cm | Uncontrolled coagulopathy; failure of closure devices | Full-thickness access; suitable for complex cases | Intentional perforation; peritonitis (5%-8%), bleeding (up to 10%) | Very high | Approximately 90%-98% (in expert hands) |

ESD is a minimally invasive technique initially developed for the resection of early gastrointestinal epithelial tumors. Over time, it has been successfully adapted for the removal of select subepithelial tumors, including GISTs. ESD allows for en bloc resection of tumors, which ensures clear histologic margins and eliminates the need for more invasive surgical interventions. This approach provides the potential for curative treatment, especially when the tumor is localized and accessible by endoscopic means[18,19].

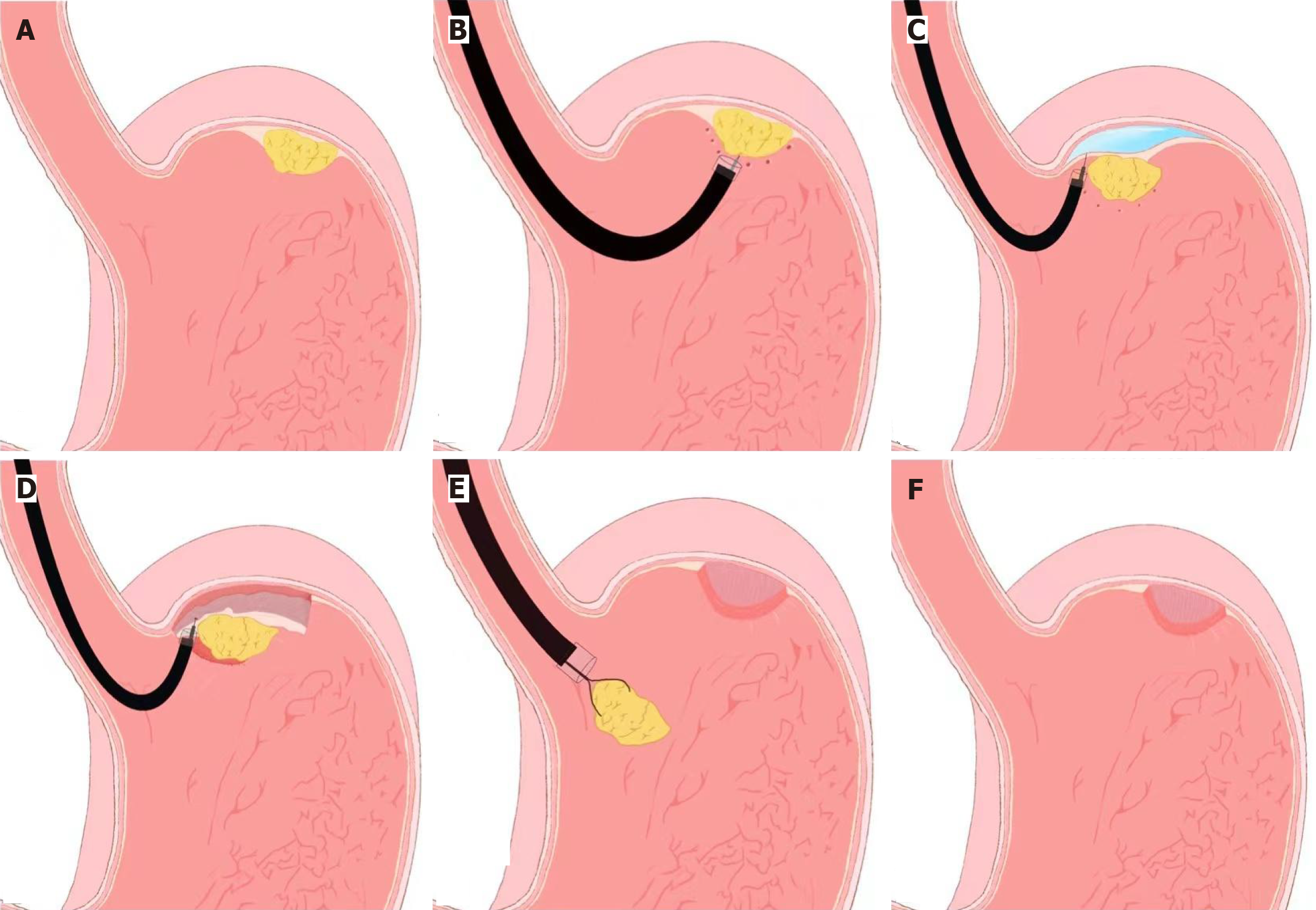

The procedure begins with careful visualization of the tumor site, followed by precise marking around the lesion to delineate the resection boundaries. A submucosal injection is then performed to lift the lesion from the surrounding tissue, creating a better plane for dissection. The mucosal and submucosal layers are then incised using specialized knives, such as a hook knife or insulated-tip knife, allowing the tumor to be gradually dissected. During the procedure, any intraoperative complications, such as bleeding or perforation, are managed promptly to prevent adverse outcomes. Once the tumor is completely resected, the defect is closed using endoscopic clips or suturing devices, depending on the size of the defect and the anatomical location (Figure 1).

Recent studies have demonstrated that ESD for gastric GISTs is associated with high complete resection rates and generally acceptable complication rates. For instance, a number of clinical studies have shown that outcomes for ESD are comparable to laparoscopic wedge resection for tumors smaller than 2 cm, with the added benefit of preserving gastric tissue and function[20]. In cases of early-stage GISTs or those in favorable locations, ESD can provide a minimally invasive, effective, and safe alternative to traditional surgery.

The most common adverse events associated with ESD include intraoperative bleeding (up to 15%) and perforation (reported in 1%-8% of cases), with higher rates in tumors arising from the muscularis propria or located near the gastric cardia[21,22]. Intraprocedural bleeding is typically managed using hemostatic forceps, argon plasma coagulation, or clipping. Perforations are closed with through-the-scope clips or over-the-scope clips (OTSC) depending on the size of the defect. Prophylactic clipping is sometimes employed after deep dissection to prevent delayed perforation or bleeding. Use of carbon dioxide insufflation and adequate submucosal lifting solutions also reduce tissue injury and facilitate safer dissection.

Despite these challenges, ESD remains a highly valuable option for treating GISTs, particularly when performed by skilled and experienced endoscopists. The technique is especially beneficial for tumors located in areas that are difficult to access surgically or for patients who are not candidates for more invasive surgery. However, there is still a need for large, prospective, multicenter studies with long-term follow-up data to better define the indications, patient selection criteria, and standardized protocols for ESD in GIST management. Such research would help refine the technique, reduce complications, and further establish its role in the treatment of GISTs.

ESE was developed to overcome the limitations of ESD when dealing with GISTs that originate from the deeper layers of the gastrointestinal wall, particularly the muscularis propria. Unlike ESD, which is effective primarily for tumors confined to the mucosa and submucosa, ESE allows for more extensive dissection into the deeper muscular layers, making it a preferred option for intramural tumors, especially those located in anatomically complex regions such as the gastric cardia[23].

The procedural steps of ESE are similar to ESD, with the key difference being the depth of dissection into the mus

ESE has demonstrated high rates of en bloc resection, meaning the tumor is removed in a single piece, which is crucial for ensuring clear histologic margins and minimizing the risk of recurrence. Numerous case series and cohort studies have reported favorable outcomes with ESE, including low recurrence rates and high resection success, particularly for tumors located in challenging regions[24]. Compared to traditional surgical resection, ESE has the advantage of faster recovery, shorter hospital stays, and improved postoperative quality of life, making it a highly attractive alternative to invasive surgery[25].

However, ESE is a technically demanding procedure and requires significant expertise and experience in advanced endoscopic techniques. The procedure’s complexity makes it suitable only for specialized centers with trained en

ESE is a powerful tool for the resection of GISTs located in the muscularis propria, offering several advantages over traditional surgery, including minimal invasiveness and reduced recovery time. However, given its technical demands and the associated risks, it should be performed only in centers with specialized training and experience. Ongoing research and refinement of techniques will likely expand the role of ESE in the treatment of GISTs and other subepithelial tumors.

STER is an innovative technique that offers a minimally invasive solution for the removal of intramural tumors, especially those located within the muscularis propria. This technique involves the creation of a submucosal tunnel, allowing for tumor resection while preserving the overlying mucosal integrity. By maintaining mucosal layers intact, STER sig

The procedural steps for STER include: (1) EUS assessment: The tumor is carefully evaluated using EUS to determine its size, location, and depth of invasion; (2) Submucosal injection: A solution is injected to lift the mucosa and create space for the subsequent resection; (3) Mucosal incision and tunnel creation: A mucosal incision is made, and a tunnel is created between the mucosa and the muscularis propria, allowing for safe tumor resection; (4) Dissection and removal: The tumor is carefully dissected from its surrounding tissues and removed through the tunnel; and (5) Closure: The mucosal entry point is closed using endoscopic clips to prevent leakage and reduce the risk of complications.

Recent studies have shown that STER provides high complete resection rates, exceeding 95%, with low recurrence rates within short-term follow-up periods[28]. Although the procedure is generally well tolerated, some complications have been reported, including gas-related events such as subcutaneous emphysema or pneumomediastinum, pleural effusion, and mucosal injury. These complications are typically self-limiting and managed conservatively[29].

Although STER preserves mucosal integrity, it carries specific risks such as subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastinum (2%-6%), and rare mucosal perforations. Gas-related events are usually self-limiting and managed conservatively. Tight closure of the mucosal entry site using endoclips is essential to minimize leakage and infection. In challenging anatomical sites, such as the gastric fundus, tunneling direction and extent must be carefully planned to avoid misorientation or mucosal tension.

EFTR is a specialized procedure designed to remove tumors that involve all layers of the gastrointestinal wall, including the serosa. EFTR is particularly valuable for lesions that cannot be effectively treated using conventional endoscopic methods like ESD or STER, especially when they are deeply embedded in the muscularis propria[30].

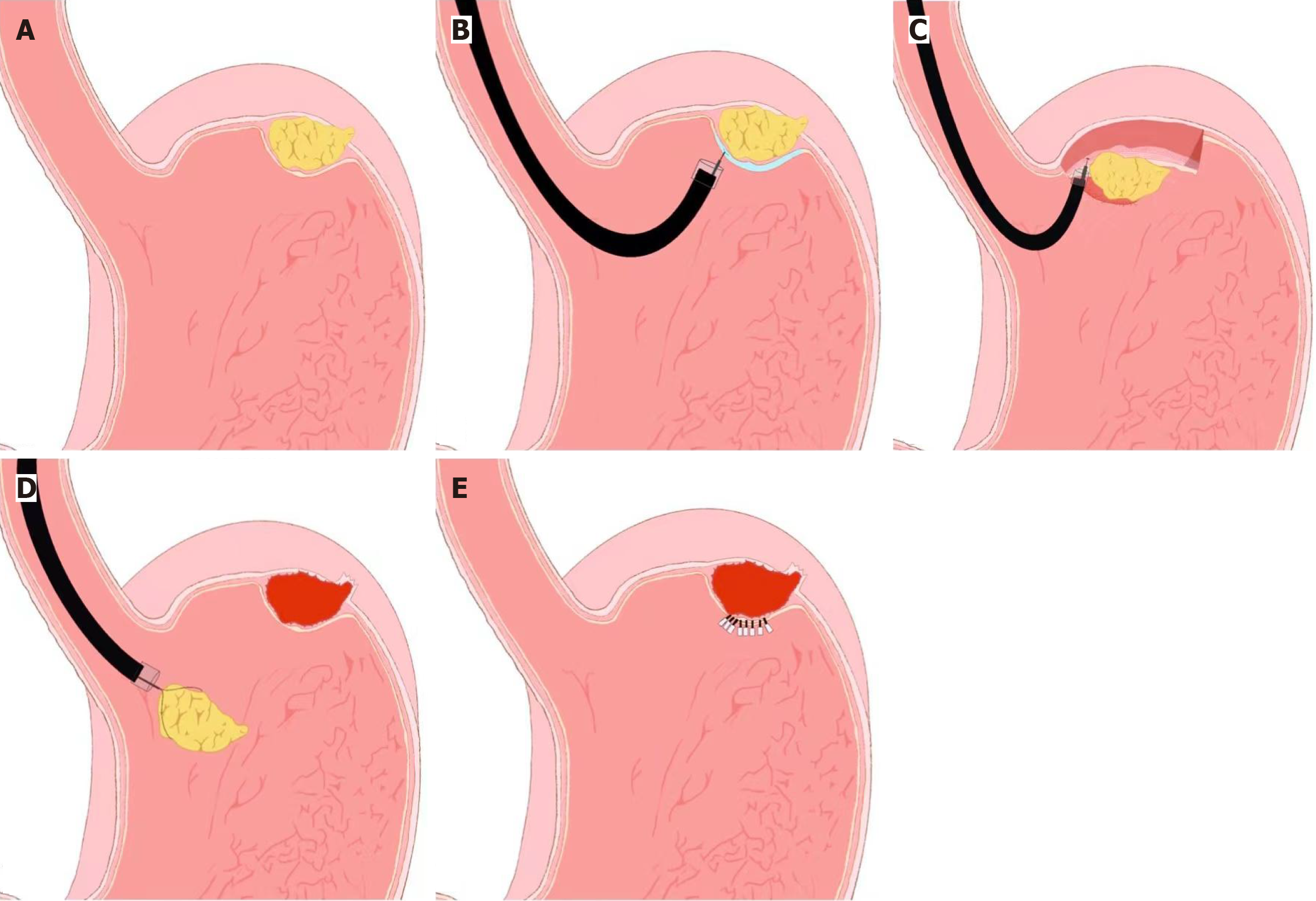

The EFTR procedure typically follows these steps: (1) Lesion marking: The tumor is carefully marked using an endoscope to delineate its boundaries; (2) Submucosal injection: A lifting solution is injected to elevate the lesion and facilitate access to deeper layers; (3) Circumferential mucosal and submucosal incision: An incision is made around the tumor to gain access to the deeper layers; (4) Serosal dissection: The dissection continues through the serosal layer, allowing for complete tumor removal; (5) Full-thickness resection: The tumor is removed in its entirety, including all layers of the gastrointestinal wall; and (6) Defect closure: The defect created by the resection is closed using endoscopic clips, OTSC, or suturing devices (Figure 2). EFTR was first introduced by Wang et al[30] for the management of gastric subepithelial tumors, and subsequent studies have demonstrated its feasibility and safety in expert hands. Although EFTR is technically more complex and associated with longer procedure times, it has been shown to achieve oncologic outcomes comparable to laparoscopic resection for small GISTs[31].

Common complications associated with EFTR include bleeding, localized peritonitis, and abdominal distention. EFTR involves intentional full-thickness perforation, with bleeding occurring in up to 10% and localized peritonitis in 5%-8% of cases. The use of OTSCs or laparoscopic backup ensures secure closure and containment of gastrointestinal contents. To mitigate complications, full-thickness dissection is performed under low insufflation pressure, and sterile irrigation may be used to reduce bacterial contamination. Postoperative antibiotics and fasting are typically implemented to support healing and prevent infection[32,33].

As EFTR continues to evolve, it has become a powerful tool in the armamentarium of advanced endoscopy, particularly for patients who are poor candidates for surgical resection or for those with tumors in difficult-to-access areas. Further refinement of the technique, along with expanded clinical studies and long-term follow-up, is necessary to fully establish EFTR as a standard treatment option for GISTs.

The primary goal of endoscopic therapy for GISTs is to achieve complete resection while minimizing procedural compli

Recent evidence, along with current guideline recommendations, supports endoscopic resection for GISTs that are larger than 2 cm or those exhibiting high-risk features on EUS, such as irregular margins, heterogeneous echotexture, or ulceration. Conversely, tumors smaller than 2 cm without concerning features are generally managed with regular surveillance, with periodic follow-up using imaging and EUS. Despite these guidelines, the optimal management strategy for small GISTs remains a topic of debate. While some small tumors may remain stable, others may demonstrate unexpected growth or malignant transformation over time. Consequently, individualized management plans that consider tumor characteristics, patient preferences, and institutional capabilities are essential for optimizing patient care.

The choice of endoscopic resection technique is largely determined by tumor size, location, and the degree of invasion. For example, ESD is often the preferred approach for lesions located in the gastric body, while STER is more appropriate for tumors located in the gastric cardia or esophagus. EFTR, including over-the-scope clip (OTSC)-assisted methods, is frequently used for larger or more deeply situated lesions. Importantly, the selection of the appropriate technique is also influenced by the skill and experience of the endoscopist, as well as the availability of advanced resection devices in the clinical setting.

Regional disparities in training and device availability continue to impact the global adoption and application of endoscopic resection for GISTs. For instance, EFTR is widely practiced in China, despite limited access to OTSC devices, while ESD is less frequently performed in Europe due to the absence of comprehensive training programs. In fact, many European endoscopists must travel to East Asia to undergo specialized training in these techniques, which limits the widespread adoption of these methods in Europe and other parts of the world.

Additionally, emerging technologies such as robotic-assisted endoscopy, computer-assisted diagnostic systems (e.g., AI-based EUS interpretation), and novel resection or closure devices (e.g., magnetic compression clips, barbed sutures) hold promise in enhancing the precision, safety, and efficiency of endoscopic procedures. Clinical trials are currently underway to assess these innovations, particularly in complex anatomical areas or for tumors > 5 cm. Furthermore, hybrid techniques that integrate laparoscopic and endoscopic approaches may expand the indications of minimally invasive treatment.

Moving forward, collaborative, prospective, multicenter studies with long-term follow-up are urgently needed to validate the oncologic safety, cost-effectiveness, and procedural standardization of these endoscopic techniques. Esta

| 1. | Zhang Q, Gao LQ, Han ZL, Li XF, Wang LH, Liu SD. Effectiveness and safety of endoscopic resection for gastric GISTs: a systematic review. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2018;27:127-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Shichijo S, Abe N, Takeuchi H, Ohata K, Minato Y, Hashiguchi K, Hirasawa K, Kayaba S, Shinkai H, Kobara H, Yamashina T, Ishida T, Chiba H, Ono H, Mori H, Uedo N. Endoscopic resection for gastric submucosal tumors: Japanese multicenter retrospective study. Dig Endosc. 2023;35:206-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Nabi Z, Ramchandani M, Sayyed M, Darisetty S, Kotla R, Rao GV, Reddy DN. Outcomes of submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection in upper gastrointestinal sub-epithelial tumors. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2019;38:509-517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Liu J, Tan Y, Liu D, Li C, Le M, Zhou H. Factors predicting technical difficulties during endoscopic submucosal excavation for gastric submucosal tumor. J Int Med Res. 2021;49:3000605211029808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wannhoff A, Nabi Z, Moons LMG, Haber G, Ge PS, Dertmann T, Deprez PH, Korcz W, Bouvette C, Mueller J, Tribonias G, Grande G, Kim JJ, Weich A, Heinrich H, Mollenkopf M, George J, Pioche M, Azzolini F, Kouladouros K, Boger P, Hayee B, Bilal M, Bastiaansen BAJ, Caca K; Upper GI FTRD Study Group. International, Multicenter Analysis of Endoscopic Full-Thickness Resection of Duodenal Neuroendocrine Tumors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2025;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Szczepaniak K, Nasierowska-Guttmejer A. The occurrence of gastrointestinal stromal tumors with second malignancies - Case series of a single institution experience. Pathol Res Pract. 2021;228:153662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chen Q, Yu M, Lei Y, Zhong C, Liu Z, Zhou X, Li G, Zhou X, Chen Y. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection for large gastric stromal tumors. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2020;44:90-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bang CS, Baik GH, Shin IS, Suk KT, Yoon JH, Kim DJ. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric subepithelial tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Korean J Intern Med. 2016;31:860-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jiao R, Zhao S, Jiang W, Wei X, Huang G. Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection of Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumours: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12:4055-4061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Meng Y, Li W, Han L, Zhang Q, Gong W, Cai J, Li A, Yan Q, Lai Q, Yu J, Bai L, Liu S, Li Y. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection versus laparoscopic resection for gastric stromal tumors less than 2 cm. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:1693-1697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang S, Shen L. Efficacy of Endoscopic Submucosal Excavation for Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors in the Cardia. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2016;26:493-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chen Y, Wang M, Zhao L, Chen H, Liu L, Wang X, Fan Z. The retrospective comparison between submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection and endoscopic submucosal excavation for managing esophageal submucosal tumors originating from the muscularis propria layer. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:417-428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jian G, Tan L, Wang H, Lv L, Wang X, Qi X, Le M, Tan Y, Liu D. Factors that predict the technical difficulty during endoscopic full-thickness resection of a gastric submucosal tumor. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2021;113:35-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wadhwa V, Franco FX, Erim T. Submucosal Tunneling Endoscopic Resection. Surg Clin North Am. 2020;100:1201-1214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Liu BR, Song JT. Submucosal Tunneling Endoscopic Resection (STER) and Other Novel Applications of Submucosal Tunneling in Humans. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2016;26:271-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gluzman MI, Kashchenko VA, Karachun AM, Orlova RV, Nakatis IA, Pelipas IV, Vasiukova EL, Rykov IV, Petrova VV, Nepomniashchaia SL, Klimov AS. Technical success and short-term results of surgical treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: an experience of three centers. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tu S, Huang S, Li G, Tang X, Qing H, Gao Q, Fu J, Du G, Gong W. Submucosal Tunnel Endoscopic Resection for Esophageal Submucosal Tumors: A Multicenter Study. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2018;2018:2149564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tan Y, Tang X, Guo T, Peng D, Tang Y, Duan T, Wang X, Lv L, Huo J, Liu D. Comparison between submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection and endoscopic full-thickness resection for gastric stromal tumors originating from the muscularis propria layer. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:3376-3382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | He CH, Lin SH, Chen Z, Li WM, Weng CY, Guo Y, Li GD. Laparoscopic-assisted endoscopic full-thickness resection of a large gastric schwannoma: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2022;14:362-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 20. | Wang G, Xiang Y, Miao Y, Wang H, Xu M, Yu G. The application of endoscopic loop ligation in defect repair following endoscopic full-thickness resection of gastric submucosal tumors originating from the muscularis propria layer. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2022;57:119-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Granata A, Martino A, Ligresti D, Zito FP, Amata M, Lombardi G, Traina M. Closure techniques in exposed endoscopic full-thickness resection: Overview and future perspectives in the endoscopic suturing era. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2021;13:645-654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Guo JT, Zhang JJ, Wu YF, Liao Y, Wang YD, Zhang BZ, Wang S, Sun SY. Endoscopic full-thickness resection using an over-the-scope device: A prospective study. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:725-736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hashimoto Y, Abe N, Nunobe S, Kawakubo H, Sumiyoshi T, Yoshida N, Morita Y, Terashima M, Saze Z, Onimaru M, Otsuji E, Hoteya S, Yamashita H, Fujimura T, Oyama T, Ohata K, Shichijo S, Tanabe K, Shuto K, Ikeya T, Shinohara H, Tanabe S, Hiki N. Outcomes of laparoscopic and endoscopic cooperative surgery for gastric submucosal tumors: A retrospective multicenter study at 21 Japanese institutions. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2024;8:778-786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sekiguchi M, Suzuki H, Takizawa K, Hirasawa T, Takeuchi Y, Ishido K, Hoteya S, Yano T, Tanaka S, Toya Y, Nakagawa M, Toyonaga T, Takemura K, Hirasawa K, Matsuda M, Yamamoto H, Tsuji Y, Hashimoto S, Maeda Y, Oyama T, Takenaka R, Yamamoto Y, Shimazu T, Ono H, Tanabe S, Kondo H, Iishi H, Ninomiya M, Oda I; J-WEB/EGC group. Potential for expanding indications and curability criteria of endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer in elderly patients: results from a Japanese multicenter prospective cohort study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2024;100:438-448.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Milatiner N, Khan M, Mizrahi M. Getting the gist of GI stromal tumors: diving deeper than endoscopic submucosal dissection. VideoGIE. 2023;8:239-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Cao B, Lu J, Tan Y, Liu D. Efficacy and safety of submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection for gastric submucosal tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2021;113:52-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Liu L, Xu X, Wang Q, Feng Y, Lu F, Tian Q, Shi D, Li R, Chen W. An evaluation of the use of double-curved endoscopes for gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2023;32:112-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Keung EZ, Raut CP. Management of Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors. Surg Clin North Am. 2017;97:437-452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Shichijo S, Uedo N, Sawada A, Hirasawa K, Takeuchi H, Abe N, Miyaoka M, Yao K, Dobashi A, Sumiyama K, Ishida T, Morita Y, Ono H. Endoscopic full-thickness resection for gastric submucosal tumors: Japanese multicenter prospective study. Dig Endosc. 2024;36:811-821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Wang L, Ren W, Fan CQ, Li YH, Zhang X, Yu J, Zhao GC, Zhao XY. Full-thickness endoscopic resection of nonintracavitary gastric stromal tumors: a novel approach. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:641-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Shah A, Thite P, Hansen T, Kendall BJ, Sanders DS, Morrison M, Jones MP, Holtmann G. Links between celiac disease and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;37:1844-1852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 32. | Hu J, Ren M, Zhao Y, Lu G, Lu X, Yin Y, Zhao Q, She J, He S. A new endoscopic technique for specific gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a retrospective cohort study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2021;56:1371-1375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Joo MK, Park JJ, Lee YH, Lee BJ, Kim SM, Kim WS, Yoo AY, Chun HJ, Lee SW. Clinical Efficacy and Safety of Endoscopic Treatment of Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors in the Stomach. Gut Liver. 2023;17:217-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/