Published online Oct 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i10.108664

Revised: July 20, 2025

Accepted: August 25, 2025

Published online: October 27, 2025

Processing time: 132 Days and 23.8 Hours

Endoscopic cold snare resection (CSP) can enhance postoperative recovery and minimize bleeding risk in patients with 5-15 mm colorectal polyps. However, more detailed evaluations are required to assess their advantages over conventional methods.

To evaluate the effects of endoscopic CSP on postoperative recovery and bleeding risk in patients with 5-15 mm colorectal polyps.

This randomized controlled study included 193 patients (mean age: 57.91 ± 5.41 years; 97 men and 96 women) with 5-15 mm colorectal polyps treated at Dongyang People's Hospital between March and June 2023. The patients were randomly assigned to the experimental group (n = 100), who underwent CSP, and the control group (n = 93), who underwent conventional endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR). Operation time, hospital stay, dietary status, and bleeding rate within 3 days were compared.

The CSP group had significantly shorter operation times (15.02 ± 2.44 minutes vs 18.78 ± 5.48 minutes, P < 0.001) and hospital stays (3.11 ± 1.08 days vs 4.89 ± 1.35 days, P < 0.001) than the EMR group. The fasting rate on the day of surgery was also lower in the CSP group (P < 0.05). The complete resection rates were si

CSP was safe and efficient for removing 5-15 mm colorectal polyps, offering faster recovery and comparable safety to EMR. The procedural efficiency of CSP supports its broad clinical application.

Core Tip: We compared endoscopic cold snare polypectomy (CSP) with conventional endoscopic mucosal resection in 193 patients with 5-15 mm colorectal polyps. CSP demonstrated advantages in postoperative recovery, including shorter operative time, reduced hospitalization, and lower fasting rates on the day of surgery. Despite similar complete resection rates and no perforation in both groups, CSP showed a marginally lower but statistically comparable bleeding risk within 3 postoperative days postoperatively. With comparable safety profiles and superior recovery outcomes, CSP has emerged as a practical option for small-to-medium-sized colorectal polyps aligned with fast-track surgical goals.

- Citation: Lv LL, Ying XX, Wu HM, Shi XY, Zhang QQ, Zhao H. Postoperative recovery and bleeding risk after endoscopic snare cold resection in patients with 5-15 mm colorectal polyps. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(10): 108664

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i10/108664.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i10.108664

Colorectal polyps are polypoid lesions that protrude from the mucosal surface of the colorectum into the intestinal lumen. These lesions are commonly observed in the digestive system. Pathogenic factors are derived from hyperplasia of the intestinal mucosa. However, in the initial stages, owing to their small size, no typical symptoms were observed. In particular, polyps with diameters of < 1 cm are mostly detected during routine physical examinations[1]. As polyps continue to grow, patients gradually develop symptoms, such as bloody stools, intestinal obstruction, and abdominal pain, and a certain risk of cancer exists. Early detection and resection are effective methods for preventing colorectal polyps[2]. Endoscopic surgery, which is characterized by minimal invasion and reduced bleeding, is widely used for the treatment of this disease. With the help of an endoscope, the location and size of the polyps can be clearly identified, and resection can be completed using an endoscope. Conventional endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) indicates that for colorectal polyps, an injection is first performed into the submucosa to make it significantly bulge and form a submucosal fluid cushion. A snare is used to encircle the polyp, and an electrocoagulation knife is used for resection. The wound surface is sutured with a Harmony clip. However, bleeding and perforation can occur postoperatively[3]. Endoscopic cold snare polypectomy (CSP) is an endoscopic surgery in which a cold snare for removing gastrointestinal polyps. Compared with the traditional thermal resection, it does not require the use of an electrocoagulation knife, reducing the risk of thermal damage to patients caused by the electrocoagulation knife. Several studies have shown[4] that it has a significant effect on the removal of polyps less than 10 mm in size.

However, the current evidence on CSP mainly focuses on diminutive and small polyps (≤ 10 mm), and data on its effectiveness and safety for polyps measuring 11-15 mm are limited. Considering that polyps in the 11-15 mm range are more likely to be adenomatous and potentially precancerous, evaluating whether CSP can be safely extended to this size category is of important clinical significance. Moreover, larger polyps may pose a greater risk of incomplete resection or bleeding if not appropriately managed. Therefore, whether CSP can maintain its advantages in operative safety and recovery for polyps > 10 mm remains uncertain. This constitutes a critical research gap that this study aims to address.

In a study by a foreign scholar, CSP was compared with EMR for the treatment of 5-10 mm colonic polyps. No significant difference in the complete resection rate of polyps or operation-related adverse events was observed between the CSP and cold EMR groups, although the operation time for CSP was shorter[5]. Building on these findings, our study investigated the application of CSP in a broader 5-15 mm range, aiming to determine whether its benefits extend to medium-sized polyps.

To further analyze the application effects of CSP and EMR in patients with 5-15 mm colorectal polyps, this study divided 193 patients with colorectal polyps admitted to Dongyang People's Hospital into different treatment groups, aiming to clarify the impact of different surgical methods on patients' postoperative recovery and bleeding risk.

A total of 193 patients with colorectal polyps admitted to Dongyang People's Hospital between March 2023 and June 2023 were selected. The patients should meet the diagnostic criteria for colorectal polyps[6].

The inclusion criteria: (1) The diameter of the polyp was ≥ 5 mm and ≤ 15 mm; (2) The patients' vital signs were stable after the operation and they could cooperate to complete the study; (3) The clinical data were complete; (4) They met the indications for endoscopic surgery; and (5) The patients voluntarily signed the informed consent form.

The exclusion criteria: (1) Patients who had received anticoagulant treatment within 1 week preoperatively; (2) Patients with hematological diseases or coagulation disorders; (3) Patients with other malignant tumors; (4) Patients with impaired liver and kidney functions; (5) Patients with a history of intestinal tumors; (6) Patients whose intestinal cleansing did not meet the standard; and (7) Patients diagnosed with familial polyposis.

The general characteristics of the patients in the two groups (except for polyp location) were comparable (P > 0.05), and no selection bias was noted. The difference in the locations of the polyps was considered to be due to the randomness of the selected research participants, and the specific location characteristics of the polyps were not fixed. Statistically significant differences were observed (Table 1).

| General information | Experimental group (n = 100) | Control group (n = 93) | t/χ2 | P value |

| Age | 58.64 ± 5.33 | 57.11 ± 5.45 | 1.971 | 0.050 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 48 | 49 | 0.424 | 0.515 |

| Female | 52 | 44 | ||

| Smoking history (yes/no) | 20/80 | 22/71 | 0.378 | 0.538 |

| Alcohol consumption history (yes/no) | 11/89 | 17/76 | 2.059 | 0.151 |

| Diabetes (yes/no) | 9/91 | 4/89 | 1.694 | 0.193 |

| Coronary heart disease (yes/no) | 5/95 | 2/91 | 1.119 | 0.290 |

| Family history of colorectal cancer (yes/no) | 4/96 | 2/91 | 0.547 | 0.459 |

| Location of polyp | ||||

| Colon transversum | 5 | 24 | 16.338 | < 0.001 |

| Left hemicolon | 59 | 56 | 0.030 | 0.864 |

| Right hemicolon | 20 | 20 | 0.066 | 0.797 |

| Hepatic flexure of colon | 7 | 1 | 4.257 | 0.039 |

Patients were randomly assigned to the control or experimental group in a 1:1 ratio using a computer-generated random number table. Group allocation was concealed using sealed opaque envelopes and implemented by an independent research assistant who was not involved in treatment or outcome assessment.

After the patients were admitted to the hospital, gastroscopy and colonoscopy were performed, and vital signs, such as electrocardiography, were monitored. On the first preoperative day, patients were instructed to adjust their diet to a liquid diet. After dinner on the same day and in the early morning of the operation, the patients were orally administered Compound Polyethylene Glycol Electrolyte Powder (Jiangxi Hengkang Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Approval Number: H20020031), and one sachet was mixed with 1000 mL of warm boiled water until clear water-like stools were excreted to complete the intestinal preparation. Before surgery, an electronic colonoscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was used to record the location, size, and number of the colorectal polyps.

The control group underwent conventional EMR. Intravenous general anesthesia with propofol was administered to maintain anesthesia during the operation. A disposable endoscopic injection needle was inserted through the endoscopic biopsy channel. Normal saline was injected 1-2 mm from the polyp edge. After the polyp bulged, it was completely ligated using a snare and resected using a high-frequency electrocoagulation knife. The wound surface was closed with titanium clips and the operation was completed.

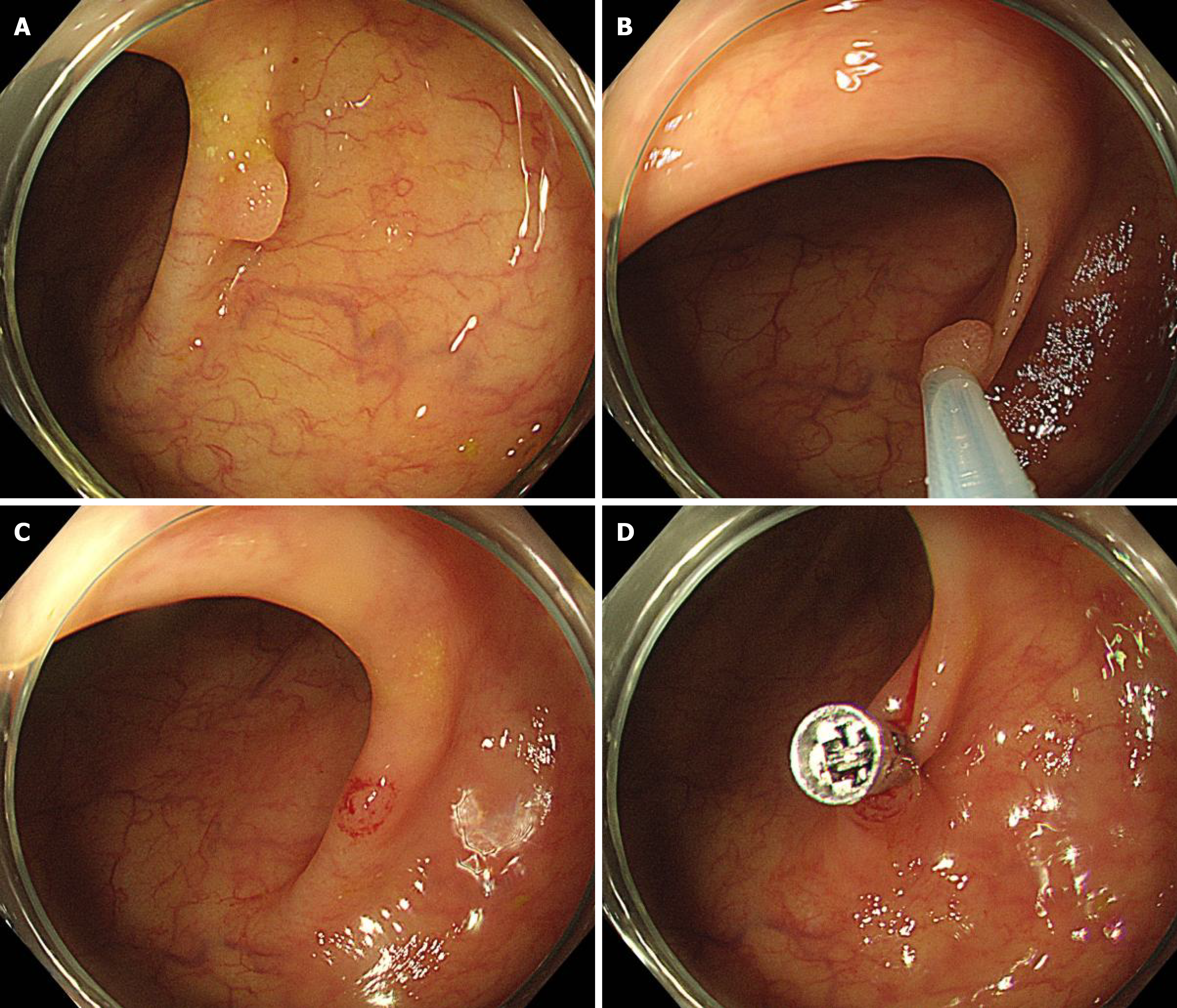

The experimental group underwent endoscopic cold snare resection. A snare (CAPTIVATOR II, with diameters of 10 and 25 mm, Boston Scientific Corporation) was selected for CSP resection. The method of anesthesia for the patients was the same as that for the control group. An electronic colonoscope was used to determine the polyp location. A cold snare was used to ligate the base of the polyp, tighten it, and press it downward towards the intestinal wall to completely separate and cut off the polyp. The specimen was recovered, the wound surface was closed with titanium clips for hemostasis, and the operation was completed. The specific operational steps are shown in Figure 1.

(1) The postoperative recovery effects in the two groups were compared. The operation time, complete polyp resection rate, postoperative perforation rate, postoperative infection rate, hospital stay, and postoperative dietary status of the patients in the two groups were recorded. The judgment standard for complete resection of polyps is observing the resected area using an endoscope. If the wound surface was flat, no residual polypoid tissue was noted, the surrounding mucosa was smooth and continuous, and no protrusion of raised or abnormal tissue was observed; and (2) Postoperative bleeding rates were compared between groups. The bleeding status of the patients in the two groups was recorded within 3 days postoperatively. If a patient experienced multiple bleeding episodes, it was recorded as one case.

The SPSS 26.0 software and GraphPad Prism 8.0 software were used for analysis. Significance was set at P < 0.05. Measurement data are described by (mean ± SD) and tested by independent sample t-test. The recurrence and bleeding rates were counted, described as n (%), and tested using the χ2 test.

The operative time and hospital stay in the experimental group were significantly shorter than in the control group (P < 0.05; Table 2). In the control group, 91 patients fasted on the day of the operation, and 2 patients had a liquid diet on that day. In the experimental group, 28 patients fasted on the day of the operation, 31 had a liquid diet, 40 had a semi-liquid diet, and 1 had a soft diet. The fasting rate on the day of the operation was lower in the experimental group than in the control group (P < 0.05). No significant difference in the complete polyp resection rate was observed between the experimental and control groups (P > 0.05). No perforation in any of the patients was observed in either group, and no significant difference in the incidence of infection was observed between the two groups (P > 0.05; Table 3).

| Group | Case | Operative time (minute) | Length of stay (day) |

| Control | 93 | 18.78 ± 5.48 | 4.89 ± 1.35 |

| Experimental | 100 | 15.02 ± 2.44 | 3.11 ± 1.08 |

| t | 6.230 | 10.148 | |

| P value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Group | Case | Polyp complete resection rate | Postoperative perforation rate | Postoperative infection rate |

| Control | 93 | 94.62 (88/93) | 0.00 (0/93) | 2.15 (2/93) |

| Experimental | 100 | 98.00 (98/100) | 0.00 (0/100) | 2.00 (2/100) |

| χ2 | 1.572 | 0.000 | 0.187 | |

| P value | 0.210 | 1.000 | 0.666 |

Although the difference in fasting rates between the groups was statistically significant, its clinical relevance lies in the faster gastrointestinal function recovery in the CSP group. The early resumption of oral intake is associated with improved patient comfort, reduced risk of nutritional compromise, and alignment with enhanced recovery protocols. This finding supports the use of CSP to promote postoperative recovery and reduce the need for prolonged dietary restriction.

The bleeding rates within 3 days postoperatively in the experimental and control groups were 2.00% (2/100) and 6.45% (6/93), respectively. No statistically significant difference was observed between the two groups (corrected χ2 = 1.414, P = 0.234).

Newly diagnosed cases of colorectal cancer account for a relatively high proportion of all malignant tumors, and its incidence and mortality rates show an upward trend, which is closely related to changes in the dietary structure and eating habits of Chinese people[7,8]. Among colonic polyps, adenomatous polyps are associated with a relatively high risk of cancer. Early implementation of relevant examinations, such as colonoscopy, to clarify the type of polyps and provide treatment is an effective measure to ensure the safety of patients' lives. Studies have confirmed[9,10] that some colorectal polyps are small and can be difficult to detect. During the surgical treatment process, owing to the small diameter of the polyps, the difficulty of the surgical operation increases, making it impossible to completely remove a small part of the polyp tissue. This increases the risk of postoperative recurrence, cancer, etc., and affects prognosis. Surgical resection is the preferred treatment for clinically. EMR is a new thermal resection method based on polypectomy and mucosal injection technology. It separates the mucosal layer from the muscular layer by elevating the diseased tissue, and uses a high-frequency electric knife for resection[11]. With the continuous improvement and perfection of clinical surgical procedures, CSP has gradually been applied to the treatment of patients with colorectal polyps[12]. Compared with EMR, it can minimize the risks of thermal injury, perforation, and bleeding after polyp resection. As it is a cold technique, this surgical method has relatively high safety[13,14].

The operation time and hospital stay in the experimental group were shorter, and the rate of fasting on the day of the operation in the experimental group was significantly lower than that in the control group (P < 0.05). No significant difference in the complete resection rate of polyps was observed between the two groups. No perforation in the patients of either group occurred, and no significant difference in the incidence of infection was observed between the two groups (P > 0.05). Thus, the CSP operation was simpler, the time for patients to return to normal after the operation was shorter, and it demonstrated a positive effect on reducing the risk of postoperative perforation and infection[15,16]. This is because as a cold resection operation without using an electrocoagulation knife, CSP reduces the impact of thermal injury on patients, and the potential risks of perforation and infection are lower[1,17-19]. This may be related to the fact that EMR can achieve a good lesion resection rate, the surgical skills of doctors, and the relatively short duration of this study[20-22].

This study noted no difference in the bleeding rate within 3 days postoperatively between the experimental and control groups (P > 0.05), suggesting that the postoperative bleeding rate in the CSP group was slightly lower than that in the control group. CSP relies on the physical resection of diseased tissue without generating a cauterization effect; thus, the risk of postoperative bleeding is significantly reduced. Doctors have a wider field of vision during surgery, and the difficulty of the surgery is lower. The damage to the tissues around the polyp is also reduced, effectively controlling the risk of postoperative bleeding in patients[23-25].

This study specifically selected patients with 5-15-mm colorectal polyps to address the current clinical uncertainty. Although CSP has been proven effective for diminutive polyps (< 10 mm), its performance for medium-sized polyps (10-15 mm) remains underexplored. Larger polyps often pose greater procedural challenges and carry a higher theoretical risk of incomplete resection or bleeding. By including patients across this size range, this study aimed to determine whether the known advantages of CSP-such as safety, simplicity, and rapid recovery-are maintained when the technique is applied to a broader, more clinically relevant patient population.

For patients with colorectal polyps, resection using the CSP operation, compared with the conventional EMR operation, could effectively control the risk of postoperative bleeding, had a higher rate of resumption of a normal diet postoperatively, and had a higher safety level during surgery, which is worth promoting. The findings of this study regarding the comparable bleeding rates between CSP and EMR are generally consistent with those of prior research; however, some earlier studies have reported significantly lower bleeding rates with CSP. This discrepancy may be attributed to differences in the study populations, polyp sizes (e.g., ≤ 10 mm vs up to 15 mm), operator experience, and definitions of post-polypectomy bleeding. In our cohort, although CSP showed a lower bleeding rate (2.0% vs 6.45%), the difference was not statistically significant, suggesting that the bleeding risk may increase slightly as CSP extends to larger polyps. These nuanced differences highlight the need for larger multicenter trials to validate CSP’s bleeding profile of CSP across various polyp sizes.

| 1. | Shaukat A, Kaltenbach T, Dominitz JA, Robertson DJ, Anderson JC, Cruise M, Burke CA, Gupta S, Lieberman D, Syngal S, Rex DK. Endoscopic Recognition and Management Strategies for Malignant Colorectal Polyps: Recommendations of the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:1916-1934.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Shaukat A, Kaltenbach T, Dominitz JA, Robertson DJ, Anderson JC, Cruise M, Burke CA, Gupta S, Lieberman D, Syngal S, Rex DK. Endoscopic Recognition and Management Strategies for Malignant Colorectal Polyps: Recommendations of the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:1751-1767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gupta S, Lieberman D, Anderson JC, Burke CA, Dominitz JA, Kaltenbach T, Robertson DJ, Shaukat A, Syngal S, Rex DK. Recommendations for Follow-Up After Colonoscopy and Polypectomy: A Consensus Update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91:463-485.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 39.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lv XH, Luo R, Lu Q, Deng K, Yang JL. Underwater versus conventional endoscopic mucosal resection for superficial non-ampullary duodenal epithelial tumors ≤20mm: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis. 2023;55:714-720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chang LC, Chang CY, Chen CY, Tseng CH, Chen PJ, Shun CT, Hsu WF, Chen YN, Chen CC, Huang TY, Tu CH, Chen MJ, Chou CK, Lee CT, Chen PY, Wu MS, Chiu HM. Cold Versus Hot Snare Polypectomy for Small Colorectal Polyps : A Pragmatic Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2023;176:311-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ferlitsch M, Hassan C, Bisschops R, Bhandari P, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Risio M, Paspatis GA, Moss A, Libânio D, Lorenzo-Zúñiga V, Voiosu AM, Rutter MD, Pellisé M, Moons LMG, Probst A, Awadie H, Amato A, Takeuchi Y, Repici A, Rahmi G, Koecklin HU, Albéniz E, Rockenbauer LM, Waldmann E, Messmann H, Triantafyllou K, Jover R, Gralnek IM, Dekker E, Bourke MJ. Colorectal polypectomy and endoscopic mucosal resection: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - Update 2024. Endoscopy. 2024;56:516-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 74.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Fan S, Zhou L, Zhang W, Wang D, Tang D. Role of imbalanced gut microbiota in promoting CRC metastasis: from theory to clinical application. Cell Commun Signal. 2024;22:232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shin AE, Giancotti FG, Rustgi AK. Metastatic colorectal cancer: mechanisms and emerging therapeutics. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2023;44:222-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 423] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sullivan BA, Noujaim M, Roper J. Cause, Epidemiology, and Histology of Polyps and Pathways to Colorectal Cancer. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2022;32:177-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tanaka S, Saitoh Y, Matsuda T, Igarashi M, Matsumoto T, Iwao Y, Suzuki Y, Nozaki R, Sugai T, Oka S, Itabashi M, Sugihara KI, Tsuruta O, Hirata I, Nishida H, Miwa H, Enomoto N, Shimosegawa T, Koike K. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for management of colorectal polyps. J Gastroenterol. 2021;56:323-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kwok K, Tran T, Lew D. Polypectomy for Large Polyps with Endoscopic Mucosal Resection. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2022;32:259-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhou C, Zhang F, We Y. Efficacy of endoscopic mucosal resection versus endoscopic submucosal dissection for rectal neuroendocrine tumors ≤10mm: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Saudi Med. 2023;43:179-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Niu C, Bapaye J, Zhang J, Liu H, Zhu K, Farooq U, Zahid S, Chathuranga D, Okolo PI 3rd. Systematic review and meta-analysis of cold snare polypectomy and hot snare polypectomy for colorectal polyps. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;38:1458-1467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Dhillon AS, Ravindran S, Thomas-Gibson S. Recurrence after endoscopic mucosal resection: there's more to it than meets the eye. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;94:376-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Albéniz E. Further new evidence regarding clipping following colorectal endoscopic mucosal resection. Endoscopy. 2021;53:1160-1161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Shahini E, Passera R, Lo Secco G, Arezzo A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of endoscopic mucosal resection vs endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal sessile/non-polypoid lesions. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2022;31:835-847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hanscom M. Cold Snare Polypectomy for Small Colorectal Polyps-Quick and Safe. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:1302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Meng QQ, Rao M, Gao PJ. Effect of cold snare polypectomy for small colorectal polyps. World J Clin Cases. 2022;10:6446-6455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mareth K, Gurm H, Madhoun MF. Endoscopic Recognition and Classification of Colorectal Polyps. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2022;32:227-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Dornblaser D, Young S, Shaukat A. Colon polyps: updates in classification and management. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2024;40:14-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Johnson GGRJ, Helewa R, Moffatt DC, Coneys JG, Park J, Hyun E. Colorectal polyp classification and management of complex polyps for surgeon endoscopists. Can J Surg. 2023;66:E491-E498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Schoefl R, Ziachehabi A, Wewalka F. Small colorectal polyps. Dig Dis. 2015;33:38-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Herszényi L. The "Difficult" Colorectal Polyps and Adenomas: Practical Aspects. Dig Dis. 2019;37:394-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Mandarino FV, Danese S, Uraoka T, Parra-Blanco A, Maeda Y, Saito Y, Kudo SE, Bourke MJ, Iacucci M. Precision endoscopy in colorectal polyps' characterization and planning of endoscopic therapy. Dig Endosc. 2024;36:761-777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bánky B, Lakatos L, Rozman P, Szijártó A. [Surgery of the colorectal polyps and early stage cancer - Expected standards]. Magy Seb. 2023;76:33-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/