Published online Aug 27, 2023. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v15.i8.1615

Peer-review started: January 19, 2023

First decision: March 14, 2023

Revised: March 27, 2023

Accepted: June 25, 2023

Article in press: June 25, 2023

Published online: August 27, 2023

Processing time: 217 Days and 16.6 Hours

The shortage of liver grafts and subsequent waitlist mortality led us to expand the donor pool using liver grafts from older donors.

To determine the incidence, outcomes, and risk factors for biliary complications (BC) in liver transplantation (LT) using liver grafts from donors aged > 70 years.

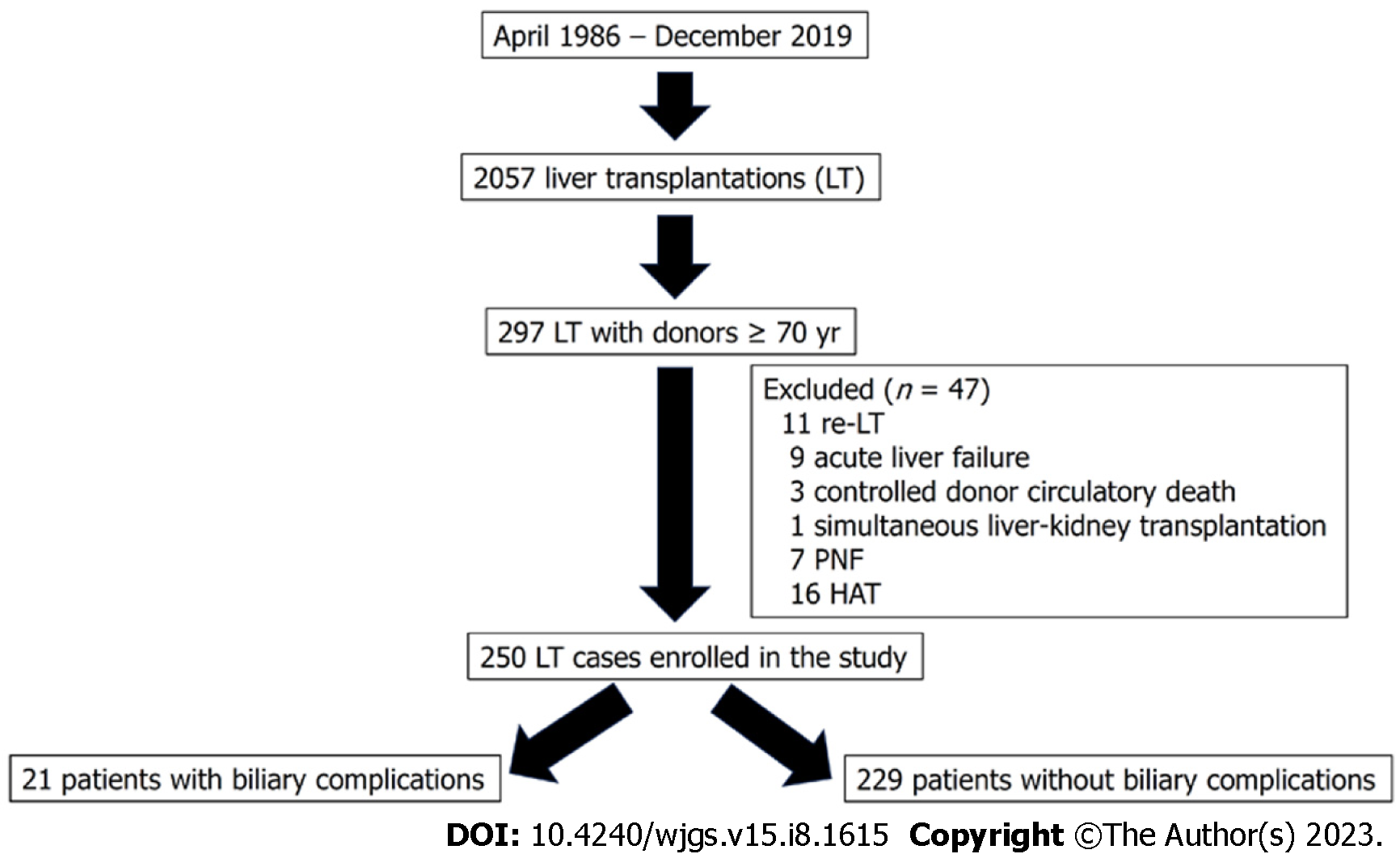

Between January 1994 and December 31, 2019, 297 LTs were performed using donors older than 70 years. After excluding 47 LT for several reasons, we divided 250 LTs into two groups, namely post-LT BC (n = 21) and without BC (n = 229). This retrospective case-control study compared both groups.

Choledocho-choledochostomy without T-tube was the most frequent technique (76.2% in the BC group vs 92.6% in the non-BC group). Twenty-one patients (8.4%) developed BC (13 anastomotic strictures, 7 biliary leakages, and 1 non-anastomotic biliary stricture). Nine patients underwent percutaneous balloon dilation and nine required a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy because of dilation failure. The incidence of post-LT complications (graft dysfunction, rejection, renal failure, and non-BC reoperations) was similar in both groups. There were no significant differences in the patient and graft survival between the groups. Moreover, only three deaths were attributed to BC. While female donors were protective factors for BC, donor cardiac arrest was a risk factor.

The incidence of BC was relatively low on using liver grafts > 70 years. It could be managed in most cases by percutaneous dilation or Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy, without significant differences in the patient or graft survival between the groups.

Core Tip: The shortage of liver grafts and subsequent waitlist mortality led us to expand the donor pool using liver grafts from older donors. Some authors have proposed a higher incidence of biliary complications (BC) using advanced age donors. In our experience, the incidence of BC was low on using liver grafts > 70 year (8.4%). Patient and graft survival were similar to patients without biliary complications and most of them could be managed by percutaneous dilation or Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy.

- Citation: Jimenez-Romero C, Justo-Alonso I, del Pozo-Elso P, Marcacuzco-Quinto A, Martín-Arriscado-Arroba C, Manrique-Municio A, Calvo-Pulido J, García-Sesma A, San Román R, Caso-Maestro O. Post-transplant biliary complications using liver grafts from deceased donors older than 70 years: Retrospective case-control study. World J Gastrointest Surg 2023; 15(8): 1615-1628

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v15/i8/1615.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v15.i8.1615

Excellent outcomes obtained with liver transplantation (LT) have led to an increasing number of candidates on the waiting list. However, the number of liver grafts remains stable. The historical liver shortage and subsequent waiting list mortality (5.2% in 2019)[1] led us to expand the donor pool using livers from extended-criteria donors, such as those with split-liver, living-related, and donor after circulatory death (DCD)[2]. However, our group principally increased the progressive utilization of livers from older donors, without an age limit, a practice already initiated in 1996[3].

There is controversial because some series have reported a significantly worse patient and graft survival[4,5] using older livers from deceased donors vs other reports defending the use of septuagenarian[6-11] and octogenarian liver grafts for non-hepatitis C virus (HCV) diseases[6,8,9,12-15]. A recent study from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients has demonstrated that the use of liver grafts ≥ 70 years provide substantial long-term survival benefits, compared to waiting for a better organ offer[16]. In contrast, several series using older livers from donors after brain death (DBD) have demonstrated significantly higher incidence of post-LT biliary complications (BC) than the use of younger livers[11,17-21], considering BC is a major source of morbi-mortality and costs[21-23]. There are no studies analyzing the incidence and outcomes of BC in patients older and younger than 70 years. There is only a recent meta-analysis that did not find significant differences in BC between recipients of liver grafts ≥ 70 years and those of grafts < 70 years[24].

Thus, the aim of the present study is to analyze specifically the incidence, outcomes, and risk factors of BC in patients who underwent LT using liver grafts from donors older than 70 years.

Between April 1986 and December 2019, 2057 LTs were performed at our hospital. Between January 1994 and December 31, 2019, 297 LTs were performed using livers older than 70 years. In order to achieve a more homogeneous study population, and avoid confounder factors we excluded 47 LTs because of the following reasons: re-transplantation (11 patients), acute liver failure (9 patients), donation after circulatory death (3 patients), simultaneous liver kidney (1 patient), primary non-function (7 patients), and hepatic artery thrombosis (HAT) (16 patients). Thus, our sample comprised 250 LTs divided into two groups as follows: patients who developed post-LT BC (n = 21) and those without BC (n = 229) (Figure 1).

A retrospective case-control study was carried out comparing both groups and following the STROBE guidelines for reporting observational studies[25].

This study was terminated on June 31, 2021, with a minimal follow-up period of 18 mo after LT. Patients were not required to give informed consent to the study because the analysis used anonymous data that was collected after each patient agreed to treatment by written consent. This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board, and it was conducted and reported according to the declaration of Helsinki. All data generated or analyzed during this study are available upon request.

General criteria for the acceptance of liver grafts older than 70 years for LT at our department were the following: good pre-procurement hemodynamic stability avoiding severe hypotension episodes or the use of high doses of vasopressors, bilirubin < 2.5 mg/dL, transaminases < 150 IU/L, intensive care unit (ICU) stay < 4 d, soft graft consistency, liver biopsy displaying the absence of hepatitis or fibrosis or macro-steatosis up to 25%, and cold ischemia time (CIT) usually not exceeding 9 h. The presence of atheroma at the bifurcation of the common hepatic artery or gastroduodenal artery was a contraindication for the use of older livers. All liver grafts were biopsied at the beginning of the procurement. Dual aortic and portal vein flush was performed using Belzer or Celsior (since 2008 to present) preservation solutions. Donor procurement was performed according to standard techniques, except for donors displaying hemodynamic instability. A rapid procurement technique was carried out in such cases. The gallbladder and biliary tract were flushed with cold saline solution at the beginning of procurement.

Recipient hepatectomy was performed using the vena cava-sparing technique (piggy-back). Portal reperfusion was performed initially, followed by arterial anastomosis and subsequent arterial reperfusion. The vascularization of the donor and recipient choledochus was carefully preserved. Biliary reconstruction was usually performed by an end-to-end choledocho-choledochostomy, without a T-tube, using interrupted sutures of polyglyconate 5-6/0. A T-tube was only placed in cases of extremely small bile ducts, diameter discrepancy between both the donor and recipient bile ducts, or intraoperative difficulties. A cholangiography through a T-tube was usually performed on postoperative day 7, closing the tube at 5-8 d thereafter. Three months after LT, a second cholangiography through the T-tube was repeated, being then removed if there were not abnormal radiological findings. Similarly, Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy (RYHJ) was only indicated inpatients with a diameter extreme discrepancy between both donor and recipient bile ducts or in case of recipients with biliary disease or prior RYHJ.

The following donor variables were evaluated: Demographics, ICU stay, the cause of death, medical history, cardiac arrest, hemodynamic instability, norepinephrine use, laboratory values (serum glucose, creatinine and sodium, liver function, and coagulation parameters), the presence of micro- and/or macro-steatosis, CIT, warm ischemia time (WIT), and preservation solutions. Moreover, the following pre-LT recipient data were assessed: demographics, LT indication, the presence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), pre-LT transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), model for end-stage liver disease (MELD), MELD- Na, D-MELD scores, United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) status, medical history, major abdominal operations, and laboratory values (serum glucose, creatinine, albumin, liver function, and hematological parameters).

The following perioperative variables were analyzed: Biliary reconstruction techniques, intraoperative transfusion, and base immunosuppression. Post-LT complications, such as early allograft dysfunction (EAD), acute renal failure, non-surgical related infections, acute rejection, HCV and HCC recurrence, non-biliary related reoperations, re-transplantation, ICU and hospital stay, patientfollow-up, overall mortality rate and causes, and patient and graft survival were also analyzed.

Non-anastomotic biliary stricture (NABS) or ischemic-type biliary lesion was defined as any stricture, dilation, or irregularity of the intra- or extra-hepatic bile ducts, with a patent hepatic artery. In contrast, anastomotic biliary stricture (ABS) was defined as a lesion localized within the biliary anastomosis[19]. Anastomotic biliary leakage (ABL) was defined as the presence of bile leak through abdominal drainage oran intra-abdominal biliary collection requiring radiological or surgical drainage.

Biliary strictures were diagnosed based on the clinical symptoms and cholestasis laboratory pattern, confirmed at the first era by ultrasound, CT scan and percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC). From 2005, a magnetic resonance imaging cholangiography (MRIC) was used for stricture confirmation. PTC was used for biliary stricture delineation and subsequent balloon dilation therapy. RYHJ was performed only after an interventional radiology failure.

EAD was defined according to Olthoff et al[26]. Post-LT acute renal failure was defined as a > 0.5% increase in the serum creatinine level or > 50% over the baseline value[27]. Acute and chronic rejection and HCV recurrence were confirmed by biopsy.

The immunosuppressive regimen consisted of cyclosporine or tacrolimus and prednisone. Mycophenolate mofetil or mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors were introduced when appropriate, and tacrolimus was reduced. Steroids were usually discontinued between 3-6 mo.

The statistical review of the study was performed by a biomedical statistician. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD and as median and interquartile range, according to the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test results. Qualitative variables were expressed as absolute frequencies (n) and relative frequencies (%). The chi-square test and Fisher's exact test were performed to compare the qualitative variables. In contrast, the continuous variables were compared using the t-test. Non-parametrictests were conducted when appropriate. The graft and patient survival rates were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Donor and recipient variables (P < 0.10) from the univariate analysis were subsequently investigated in a multivariate analysis to assess their eventual effect on the development of BC. The results were expressed as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics, version 27 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).

A total of 250 patients underwent LT using liver grafts from donors aged ≥ 70 years (175 and 75 patients were septuagenarians and older than 80 years, respectively). The overall incidence of BC in this series was 8.4%. If we divide the patients who underwent LT into two eras, donor age was similar (76.1 years in the first era vs 77.6 years in the second era; P = 0.073), and no significant differences were found (P = 0.551) regarding the rate of BC: 6.6% (4 cases) in the first era (61 LT performed between January 1994 and December 2004), and 9% (17 cases) in the second era (189 LT performed between January 2005 and December 2019).

The mean donor age was similar between the groups (BC and non-BC), and women were significantly less frequent in the BC group (P = 0.017). Moreover, we did not find differences in obesity, body mass index, ICU stay, and causes of donor death, and cerebrovascular disease was the most frequent cause of death. There were also no differences in hypertension, diabetes, hemodynamic instability, and norepinephrine use. The incidence of cardiac arrest was significantly higher in the BC group than that in the non-BC group (19% vs 5.7%; P = 0.043). Donor laboratory values were similar, except for a lower platelet count in the BC group (P = 0.016).

There were no significant differences in the rates of micro-steatosis and macro-steatosis, and the mean CIT and WIT values were similar too (Table 1).

| BC (n = 21) | Non-BC (n = 229) | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 77.5 ± 5.8 | 77.2 ± 5.2 | 0.757 |

| Sex (female), n (%) | 7 (33.3) | 138 (60.3) | 0.017 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.1 ± 5.1 | 27.4 ± 4.7 | 0.366 |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30), n (%) | 5 (23.8) | 57 (25.2) | 0.409 |

| ICU stay (h) | 34 ± 24 | 24 ± 24 | 0.964 |

| Cause of death, n (%) | |||

| Cerebrovascular | 14 (66.7) | 183 (79.9) | 0.773 |

| Head trauma | 5 (23.8) | 36 (15.7) | |

| Other | 2 (9.5) | 10 (4.4) | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 13 (61.9) | 131 (57.2) | 0.677 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 5 (23.8) | 47 (20.5) | 0.452 |

| Cardiac arrest, n (%) | 4 (19.0) | 13 (5.7) | 0.043 |

| Hemodynamic instability, n (%) | 9 (42.9) | 67 (29.3) | 0.195 |

| Norepinephrine use, n (%) | 15 (71.4) | 163 (71.2) | 0.981 |

| Laboratory values | |||

| Serum glucose (mg/dL) | 158 ± 42 | 174 ± 70 | 0.378 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.9 ± 0.5 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 0.148 |

| Serum sodium (mEq/L) | 145 ± 7 | 146 ± 8 | 0.402 |

| AST (IU/L) | 23 ± 17 | 28 ± 19 | 0.191 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 22 ± 19 | 26 ± 22 | 0.444 |

| GGT (IU/L) | 24 ± 49 | 21 ± 35 | 0.447 |

| Platelets/m3 | 134 ± 84 | 172 ± 86 | 0.016 |

| Prothrombin rate (%) | 77 ± 16 | 72 ± 23 | 0.426 |

| Partial thromboplastin time (s) | 30 ± 6 | 30.5 ± 7.3 | 0.495 |

| Steatosis (biopsy findings) , n (%) | |||

| Microsteatosis | 6 (28.6) | 39 (17.0) | 0.509 |

| Mild macrosteatosis | 4 (19.0) | 61 (26.6) | |

| Moderate macrosteatosis | 0 | 8 (3.5) | |

| Cold ischemia time (min) | 442 ± 225 | 429 ± 235 | 0.783 |

| Warm ischemia time (min) | 55 ± 15 | 55 ± 15 | 0.486 |

| Preservation solution, n (%) | |||

| Celsior | 18 (85.7) | 189 (82.5) | 0.496 |

| Belzer | 3 (14.3) | 40 (17.5) |

The median recipient age was equal in both groups, and there were no significant differences in LT indications. Pre-LT TACE as a bridging therapy in patients with HCC, MELD scores, and UNOS status demonstrated similar frequencies. Medical history, such as hypertension, diabetes, and pre-LT major abdominal operations were more frequent in the BC group, but the difference was statistically in significant. While the median values of total bilirubin were significantly lower (P = 0.036) in the BC group, the prothrombin rate was significantly higher (P = 0.030) (Table 2).

| Variables | BC (n = 21) | Non-BC (n = 229) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 59 ± 10 | 59 ± 12 | 0.767 |

| Sex (female) | 3 (14.3) | 53 (23.1) | 0.264 |

| LT indications, n (%) | |||

| Alcohol | 11 (52.4) | 97 (42.4) | 0.705 |

| HCV | 7 (33.3) | 80 (34.9) | 0.883 |

| HBV | 0 | 27 (11.8) | 0.081 |

| Biliary related | 1 (4.8) | 5 (2.2) | 0.413 |

| Other | 2 (9.5) | 20 (8.7) | 0.244 |

| HCC, n (%) | 7 (43.8) | 70 (30.6) | 0.793 |

| Pre-LT TACE, n (%) | 3 (42.9) | 31 (44.3) | 0.631 |

| MELD | 11 ± 7 | 13 ± 7 | 0.334 |

| MELD-Na | 11 ± 8 | 13 ± 8 | 0.189 |

| D-MELD | 810 ± 526 | 996 ± 510 | 0.360 |

| UNOS status, n (%) | |||

| Home | 19 (90.5) | 212 (93.4) | 0.343 |

| Hospital | 1 (4.8) | 13 (5.7) | |

| ICU | 1 (4.8) | 2 (5.2) | |

| Medical history, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 6 (28.6) | 46 (20.1) | 0.254 |

| Diabetes | 6 (28.6) | 44 (19.2) | 0.223 |

| Pre-LT major abdominal operations | 5 (23.8) | 23 (10) | 0.069 |

| Laboratory values, n (%) | |||

| Serum glucose (mg/dL) | 130 ± 56 | 128 ± 63 | 0.801 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.1 ± 0.8 | 1 ± 0.6 | 0.823 |

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | 3.6 ± 0.6 | 3.4 ± 0.6 | 0.203 |

| AST (IU/L) | 53 ± 42 | 54 ± 56 | 0.836 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 33 (33) | 33 ± 36 | 0.955 |

| GGT (IU/L) | 57 ± 129 | 61 ± 70 | 0.645 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.1 ± 0.9 | 1.7 ±2 | 0.036 |

| Leukocytes/mm3 | 4483 ± 2819 | 5356 ± 3110 | 0.063 |

| Hemoglobin (g/100 mL) | 12.6 ± 4.4) | 12.3 ± 3.1 | 0.986 |

| Platelets × 103/mm3 | 100.7 ± 75.6 | 94.2 ± 50.2 | 0.496 |

| Prothrombin rate (%) | 70.6 ± 22.2 | 65 ± 18.3 | 0.030 |

| aPTT (s) | 34.9 ± 5.3 | 36.4 ± 8.1 | 0.272 |

We observed a statistically significant difference in biliary tract reconstruction techniques between the groups (P = 0.013). Choledocho-choledochostomy without a T-tube was the most frequent technique (76.2% cases in the BC group vs 86.9% cases in the non-BC group), but the frequency of choledocho-choledochostomy with a T-tube and RYHJ was higher in the BC group.

Post-LT complications, such as EAD, acute renal failure, acute rejection, and non-biliary related reoperations, were similar between the groups. The rate of non-surgical related infections was higher, but statistically insignificant in the BC group (28.6% vs 13.1%; P = 0.062). Other complications, such as HCV and HCC recurrence rates, did not differ significantly. None of the patients who developed BC underwentre-transplantation. The median follow-up period of the BC group was lower than that of the non-BC group, but differences were not statistically significant (46 ± 56 mo vs 72 ± 95 mo; P = 0.099). Overall mortality was lower but no significant in the BC group (28.6% vs 38.9%; P = 0.352). Infections were the main cause of the death in the BC group and cardiovascular disease and malignancies were the main cause of death in the non-BV group (P = 0.041) (Table 3).

| Variables | BC (n = 21) | Non-BC (n = 229) | P value |

| Biliary reconstruction, n (%) | |||

| Chol-Chol-without T-tube | 16 (76.2) | 212 (86.9) | 0.013 |

| Chol-Chol-with T-tube | 3 (14.3) | 11 (4.8) | |

| RYHJ | 2 (9.5) | 6 (2.6) | |

| Transfusion (units) | |||

| Packed red blood cells | 7 ± 10 | 5 ± 8 | 0.147 |

| Fresh frozen plasma | 9 ± 12 | 10 ± 10 | 0.647 |

| Platelets | 1 ± 1 | 1 ± 3 | 0.100 |

| Initial immunosuppression, n (%) | |||

| Tacrolimus + steroids | 20 (95.2) | 199 (86.9) | 0.231 |

| Cyclosporine + steroids | 1 (4.8) | 30 (9.8) | |

| Early allograft dysfunction | 4 (19.0) | 32 (14.0) | 0.357 |

| Acute renal failure | 5 (23.8) | 54 (13.1) | 0.581 |

| Non-surgical related infections | 6 (28.6) | 30 (13.1) | 0.062 |

| Acute rejection | 6 (28.6) | 54 (23.6) | 0.608 |

| HCV recurrence | 1 (4.8) | 43 (18.8) | 0.085 |

| HCC recurrence | 0 | 9 (3.9) | 0.446 |

| Non-biliary related reoperation | 1 (4.8) | 12 (5.2) | 0.701 |

| Re-transplantation | 0 | 6 (2.8) | 0.643 |

| ICU stay (d) | 4 ± 5 | 4 ± 4 | 0.559 |

| Hospital stay (d) | 15 ± 13 | 12 ± 10 | 0.326 |

| Patient follow-up (mo) | 46 ± 56 | 72 ± 95 | 0.099 |

| Overall mortality rate, n (%) | 6 (28.6) | 89 (38.9) | 0.352 |

| Causes of death, n (%) | |||

| Cardiovascular disease | 1 (4.8) | 20 (8.7) | 0.041 |

| Infections | 4 (19.0) | 12 (5.2) | |

| Malignancies | 1 (4.8) | 23 (10) | |

| HCV recurrence | 0 | 13 (5.7) | |

| Other | 0 | 21 (9.3) |

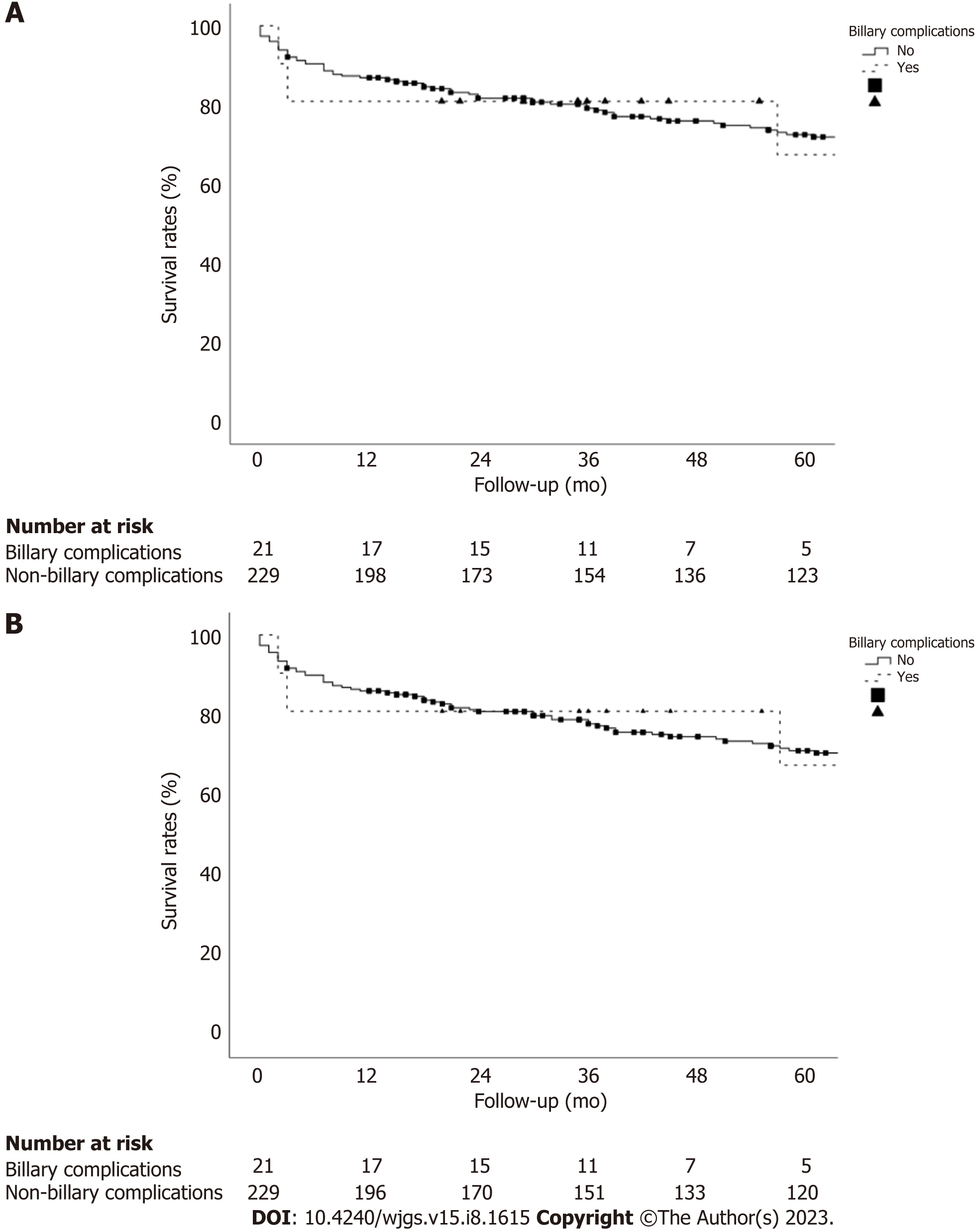

There were no significant differences in the patient and graft survival between the recipients of donors aged ≥ 70 years who developed BC vs non-BC recipients. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year patient survival rates in the BC group were 81.0%, 81.0%, and 67.5%, respectively, vs 86.9%, 80.2%, and 72.5%, respectively, in the non-BC group (P = 0.954; Figure 2A). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year graft survival rates in the BC group were 81.0%, 81.0%, and 67.5%, respectively, vs 86.0%, 78.8%, and 71.1%, respectively, in the non-BC group (P = 0.909; Figure 2B).

In the univariate analysis, donor variables, such as female donors (OR: 0.33; 95%CI: 0.13-0.85, P = 0.021), cardiac arrest (OR: 3.91; 95%CI: 1.14-13.30, P = 0.029), and platelet count (OR: 1.00; 95%CI: 1.00-1.00, P = 0.031) displayed statistically significant differences. In the multivariate analysis, while female donors (OR: 0.27; 95%CI: 0.08-0.90, P = 0.033) was a protective factor for BC, donor cardiac arrest (OR: 7.66; 95%CI: 1.52-38.61, P = 0.013) was a risk factor (Table 4).

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Donor variables | ||||

| Age (per year) | 1.01 (0.93-1.10) | 0.755 | - | - |

| Sex (female) | 0.33 (0.13-0.85) | 0.021 | 0.27 (0.08-0.90) | 0.033 |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30) (Y/N) | 1.26 (0.44-3.64) | 0.661 | - | - |

| Cause of death | ||||

| Cardiovascular vs trauma | 0.55 (0.18-1.62) | 0.143 | - | - |

| Other causes vs trauma | 1.44 (0.24-8.56) | 0.420 | ||

| Cardiac arrest (Y/N) | 3.91 (1.14-13.30) | 0.029 | 7.66 (1.52-38.61) | 0.013 |

| Donor hypertension (Y/N) | 1.21 (0.48-3.04) | 0.677 | - | - |

| Donor diabetes (Y/N) | 1.21 (0.42-3.47) | 0.722 | - | - |

| Platelets/mm3 (per unit) | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.031 | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.141 |

| Cold ischemia time (per min) | 0.99 (0.99-1.00) | 0.685 | - | - |

| Recipient variables | ||||

| Age (per year) | 1.01 (0.96-1.06) | 0.620 | - | - |

| Sex (female) | 0.55 (0.15-1.95) | 0.357 | - | - |

| Recipient hypertension (Y/N) | 1.59 (0.58-4.32) | 0.362 | - | - |

| Recipient diabetes (Y/N) | 1.68 (0.61-4.58) | 0.309 | - | - |

| HCC (Y/N) | 1.13 (0.43-2.93) | 0.792 | - | - |

| MELD (per unit) | 0.96 (0.88-1.05) | 0.481 | - | - |

| Total bilirubin (per unit) | 0.63 (0.40-1.02) | 0.160 | - | - |

| Leukocytes/mm3 (per unit) | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.221 | - | - |

| Prothrombin rate (%) (per unit) | 1.01 (0.99-1.04) | 0.195 | - | - |

| PRBC transfusion (per unit) | 1.02 (0.97-1.06) | 0.332 | - | - |

| Pre-LT major abdominal operations (Y/N) | 2.80 (0.93-8.35) | 0.064 | 3.08 (0.83-11.33) | 0.090 |

| Biliary reconstruction | ||||

| Chol-Chol-with T-tube | 3.61 (0.91-14.27) | 0.486 | - | - |

| RYHJ | 4.41 (0.82-23-67) | 0.342 | ||

The incidence of BC in 175 recipients of septuagenarian liver grafts and 75 recipients of octogenarian liver grafts was 7.4% and 10.7%, respectively (P = 0.398). The initial techniques of biliary reconstruction were choledocho-choledochostomy without a T-tube, with a T-tube, and RYHJ in 16 patients, 3 patients, and 2 patients, respectively. MRIC was used in nine patients to confirm ABS following an ultrasound. While 15 (71.4%) patients were diagnosed with BC within the first year of LT (eight ABS and seven ABL), 6 (28.6%) patients were diagnosed after the first year (five ABS and one mild NABS without any therapeutic requirement).

Of the 7 patients with ABL, 3 (42.8%) patients closed spontaneously, and 4 (57.2%) patients required reoperation (two were treated by a leakage repair, one underwent RYHJ, and the remaining patient with a prior RYHJ underwent several surgeries because of multiple biliary complications). Nine (69.2%) of the 13 patients with ABS underwent PTC balloon dilation (range: 1-6 times), and 4 patients underwent RYHJ. In addition, 4 patients also required a RYHJ procedure due to failure of prior PTC balloon dilation. During follow-up, 6 patients died among those who developed BC (5 among the recipients of septuagenarian donors, and 1 among recipients of octogenarian donors). However, only three (14.3%) ofthese deaths were related to BC (two in recipients of septuagenarian donors, and one in a recipient of an octogenarian donor) (Table 5).

| Cases | Donor age (yr) | Recipient age (yr) | LT indication | Biliary anastomosis technique | BC type | Diagnosis | Time from LT to BC | PTB dilation (times) | Reoperation: surgical procedure | Current status (causes of death) |

| Donors aged 70-79 yr (13/175, 7.4%) | ||||||||||

| 1 | M (70) | M (49) | Alcohol | Chol-chol-T tube | ABL | US | 7 d | - | - | Deceased (57 m): CV disease |

| 2 | M (73) | M (50) | Alcohol | Chol-chol-T tube | ABS | US, CT scan | 12 m | 1 | - | Deceased (88 m): tumor |

| 3 | M (76) | M (50) | Alcohol | Chol-chol | ABL | US, CT scan | 10 d | - | Roux-en-Y HJ | Deceased (1 m): BC-infection |

| 4 | M (72) | M (61) | HCV | Roux-en-Y HJ | ABS | US | 1 m | 1 | - | Deceased (3 m): aspergillus |

| 5 | F (70) | M (63) | HCV | Chol-chol | ABL | Drainage | 6 d | - | - | Deceased (1 m): BC-infection |

| 6 | M (70) | M (64) | Alcohol + HCC | Chol-chol | ABS | CT scan | 1 m | - | Roux-en-Y HJ | Alive (119 m) |

| 7 | M (73) | M (67) | HCV | Chol-chol | ABS | US, MRIC | 1 m | 4 | Roux-en-Y HJ | Alive (86 m) |

| 8 | M (75) | M (59) | HCV + HCC | Chol-chol | ABS | US, MRIC | 12 m | 4 | - | Alive (65 m) |

| 9 | F (73) | F (37) | Policystic disease | Chol-chol-T tube | ABL | Drainage | 8 d | - | Primary suture | Alive (55 m) |

| 10 | F (79) | M (69) | Cryptogenic | Chol-chol | ABS | US, MRIC | 32 m | - | Roux-en-Y HJ | Alive (46 m) |

| 11 | F (73) | M (57) | HCV + HCC | Chol-chol | ABL | Drainage | 10 d | - | - | Alive (44 m) |

| 12 | M (79) | M (63) | HCV + HCC | Chol-chol | ABL | Drainage, CT scan | 6 d | - | Primary suture | Alive (21 m) |

| 13 | M (75) | M (55) | HCV + HCC | Chol-chol | ABS | MRIC | 13 m | - | Roux-en-Y HJ | Alive (19 m) |

| Donors ≥ 80 yr (8/75, 10.7%) | ||||||||||

| 14 | M (84) | M (52) | Alcohol | Chol-chol | ABS | CT scan | 11 m | - | Roux-en-Y HJ | Alive (249 m) |

| 15 | M (85) | M (71) | Alcohol + HCC | Chol-chol | ABS | CT scan | 13 m | - | - | Alive (126 m) |

| 16 | M (89) | M (58) | Autoimmune | Chol-chol | NABS | MRIC | 21 m | - | - | Alive (52 m) |

| 17 | M (80) | M (54) | Alcohol | Chol-chol | ABS | MRIC | 5 m | 2 | Roux-en-Y HJ | Alive (48 m) |

| 18 | F (81) | F (54) | NASH | Chol-chol | ABS | MRIC | 38 m | 6 | - | Alive (45 m) |

| 19 | F (83) | M (61) | Alcohol + HCC | Chol-chol | ABS | MRIC | 16 m | 2 | Roux-en-Y HJ | Alive (39 m) |

| 20 | F (85) | M (59) | NASH | Chol-chol | ABS | CT scan, MRIC | 3 m | 3 | Roux-en-Y HJ | Alive (39 m) |

| 21 | M (84) | M (67) | SBC | Roux-en-Y HJ | ABL | Drainage, CT scan | 8 d | - | Several procedures | Deceased (2 M): BC-infection |

Before the introduction of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), the use of older livers in patients with HCV was associated with a significantly lower patient and graft survival owing to HCV recurrence[28]. However, on excluding recipients with HCV cirrhosis, the patient and graft survival did not differ between the recipients of octogenarian and septuagenarian donors[29]. Currently, the scenario has dramatically changed, and well-selected liver grafts without an age limit can be used, without the fear of HCV recurrence on treating the patients with DAA[30]. The liver is the most permissive organ, in relation to the donor age because of its regenerative property[31]. However, older livers are more susceptible to prolonged cold ischemia times[32]. Biological and chronological aging of the old liver donors is not always the same because the general status and physiologic reserve vary markedly by lifestyle factors[33] and comorbidities. To obtain good results using older livers, the donors and recipients should be selected carefully to avoid theiruse in sick patients[29].

Most BC are diagnosed within 1-year post-LT, and the overall incidence among the recipients of livers from DBD younger than 80 years reportedly ranges between 12%-44%[8,11,21,23,34-36]. In contrast, the overall incidence of BC using livers older than 80 years ranges between 6.7%-23.9%[6,13-15,29,37-39]. One of these series using only octogenarian livers reported on an overall incidence of 23.9%, corresponding17% of these patients to type NABS[38]. In other study, the same authors found the donor age ≥ 80 years as a risk factor for the development of NABS when performing a single aortic vs dual perfusion (aortic and portal) during donor procurement[39]. Three other studies compared post-LT BC for liver grafts younger and older than 70 years, and the incidence ranged between 9%-19% and 12%-15.1% in recipients of septuagenarian and octogenarian livers, respectively, without significant differences between thegroups[8,40,41]. In other comparative study, the incidence of NABS was 13% for liver grafts ≥ 65 years vs 19% for grafts < 65 years[35].

The overall rate of BC among our recipients of donors ≥ 70 years was 8.4%, without significant differences between the two groups (7.4% in recipients of septuagenarian donors vs 10.7% in recipients of donors ≥ 80 years; P = 0.398). We divided the patients into two groups according to the era of LT (beforeor after December 2004) to investigate an eventual influence of the period of LT over the incidence of BC. The age of the donor was higher in the second era, nevertheless the difference was statistically insignificant. Of note, overall rate of BC (8.4%) in our study was lower than overall rate of 12.1% previously reported in a systematic review analysis of five series of LT using livers older than 70 years[24].

Researchers have described several donor risk factors for BC, such as the use of older liver grafts, donors with extended criteria, DCD livers, macro-steatosis > 25%, atherosclerosis, the use of high viscosity preservation solution, CIT > 10 h, severe hypotension of the donor or recipient, ABO incompatibility, smallbile ducts, bile duct ischemia, anastomotic technique failure, HAT, prior bile leak, autoimmune hepatitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, or acute or chronic rejection[17,20,22,23,38,42-45]. The policy at our department on the use of donors ≥ 70 years was framed to prevent the aforementioned risk factors for BC, by performing a mandatory liver biopsy in all cases to discard livers with relevant histological alterations[29]. The use of hepatic artery pressure perfusion with low viscosity histidine-tryptophan-ketoglutarate preservation solution to improve peribiliary vascularization has been associated with lower rates of ischemic cholangiopathy[20]. This practice has been routinely performed in 207 of our LT, using Celsior solution as an alternative low viscosity solution. The use of older donors with a CIT longer than 13 h increases the risk of NABS[20], and it reduces the graft survival[5]. In our study, the median values of CIT were under 13 h in both groups and differences were not statistically significant (442 min in BC vs 429 min in non-BC; P = 0.783).

A careful preservation of arterial vascularization of donor and recipient bile ducts is an important measure to avoid BC[44]. Small bile duct diameter constitutes a risk factor for ABS[23]. A sonographic study revealed that the upper normal limit size of the bile duct in the elderly population should be set at 8.5 mm[46]. In a LT series using liver grafts of a mean age of 55 years, the common bile duct diameter ranged between 6.8 mm and 7.1 mm[47]. The use of old liver grafts could facilitate the performance of the biliary anastomosis because of aging-associated progressive duct dilation.

The technique of biliary reconstruction using a T- tube has demonstrated a higher risk of BC, which has been attributed to a higher ABL rate[23,48]. In the same way, in our series the rate of BC was significantly higher among few patients who underwent choledocho-choledochostomy with a T-tube (two cases of ABS and one of ABL).

Patients with BC were diagnosed based on the clinical features and ultrasound/doppler and were confirmed by CT scan and PTC in the first era, and more recently by MRIC. Patients with ABL were diagnosed during the first 10 d post-LT, with an evolution to spontaneous closure in three patients and the remaining four requiring reoperation. In contrast, 13 patients with ABS were diagnosed at a mean time of 12.2 mo post-LT (range: 1-38). While nine patients underwent an interventional therapy by PTC balloon dilation (1-6 times), eight underwent RYHJ. Alternatively, other authors prefer to use endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for ABS dilation[49]. Only three (14.3%) of our patients died because of BC (two recipients of septuagenarian livers and one recipient of an octogenarian liver).

We observed no significant differences in the patient and graft survival between the groups. In contrast, other authors have reported on the association between BC and significantly lower patient and graft survival[21,23,49]. Another series demonstrated an association between significantly lower patient and graft survival and more frequent incidence of NABS in recipients of octogenarian livers[38]. A different series using liver grafts younger and older than 75 years showed similar patient and graft survival between the groups, but a higher BC rate between the older group (29.6% vs 13%)[11].

The most frequent causes of mortality in octogenarian liver recipients are cardiovascular disease, HCV or HCC recurrence, infection, and the development of de novo tumors[6,12,15,37], similar to our findings, and NABS[38]. As previously reported[30], the multivariate analysis identified female donors as a protective factor of BC owing to better pre-transplant liver function. However, donor cardiac arrest was a risk factor, as demonstrated in recipients of DCD livers suffering cardiac arrest[42,50].

This study had several limitations. We collected data retrospectively for a long duration and, subjected them to some biases typical for such studies.

In conclusion, the incidence of BC in our series was lower than others previously reported, and most cases could be managed by multidisciplinary approaches (percutaneous dilation or Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy), which kept patient and graft survival unchanged. None of the patients with BC required re-transplantation. Female donor sex was a protective factor for BC, while donor cardiac arrest was a risk factor. The careful management of older liver grafts and meticulous anastomotic techniques can be associated with a low incidence of BC, confirming that livers older than 70 years are fine to use in LT.

The shortage of liver grafts and subsequent waitlist mortality led us to expand the donor pool using liver grafts from older donors.

There are no studies analyzing the incidence and outcomes of biliary complications (BC) in patients older and younger than 70 years.

The aim of this study was to determine the incidence, outcomes, and risk factors for BC in liver transplantation (LT) using liver grafts from donors aged > 70 years.

A retrospective case-control study was performed comparing patients who developed biliary complications with patients who did not after liver transplantation with donors ≥ 70 years.

Twenty-one patients (8.4%) developed biliary complications (13 anastomotic strictures, 7 biliary leakages, and 1 non-anastomotic biliary stricture). There were no significant differences in the patient and graft survival between the groups. Only three deaths were related to biliary complications. Female donors were protective factors for biliary complications and donor cardiac arrest was a risk factor.

The incidence of biliary complications was relatively low on using liver grafts > 70 years.

Prospective studies are necessary to confirm these results. It would be interesting to analyze the diameter of the bile duct and technical aspects when we perform the anastomosis.

| 1. | Spanish National Transplant Organization (ONT). Dossier de Actividad en Trasplante Hepático (Dossier on Liver Transplantation Activity). 2019. Available from: http://www.ont.es. |

| 2. | Jiménez-Romero C, Manrique A, Calvo J, Caso Ó, Marcacuzco A, García-Sesma Á, Abradelo M, Nutu A, García-Conde M, San Juan R, Justo I. Liver Transplantation Using Uncontrolled Donors After Circulatory Death: A 10-year Single-center Experience. Transplantation. 2019;103:2497-2505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Jiménez Romero C, Moreno González E, Colina Ruíz F, Palma Carazo F, Loinaz Segurola C, Rodríguez González F, González Pinto I, García García I, Rodríguez Romano D, Moreno Sanz C. Use of octogenarian livers safely expands the donor pool. Transplantation. 1999;68:572-575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Moore DE, Feurer ID, Speroff T, Gorden DL, Wright JK, Chari RS, Pinson CW. Impact of donor, technical, and recipient risk factors on survival and quality of life after liver transplantation. Arch Surg. 2005;140:273-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Reese PP, Sonawane SB, Thomasson A, Yeh H, Markmann JF. Donor age and cold ischemia interact to produce inferior 90-day liver allograft survival. Transplantation. 2008;85:1737-1744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cescon M, Grazi GL, Ercolani G, Nardo B, Ravaioli M, Gardini A, Cavallari A. Long-term survival of recipients of liver grafts from donors older than 80 years: is it achievable? Liver Transpl. 2003;9:1174-1180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Segev DL, Maley WR, Simpkins CE, Locke JE, Nguyen GC, Montgomery RA, Thuluvath PJ. Minimizing risk associated with elderly liver donors by matching to preferred recipients. Hepatology. 2007;46:1907-1918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Darius T, Monbaliu D, Jochmans I, Meurisse N, Desschans B, Coosemans W, Komuta M, Roskams T, Cassiman D, van der Merwe S, Van Steenbergen W, Verslype C, Laleman W, Aerts R, Nevens F, Pirenne J. Septuagenarian and octogenarian donors provide excellent liver grafts for transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2012;44:2861-2867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chedid MF, Rosen CB, Nyberg SL, Heimbach JK. Excellent long-term patient and graft survival are possible with appropriate use of livers from deceased septuagenarian and octogenarian donors. HPB (Oxford). 2014;16:852-858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Paterno F, Wima K, Hoehn RS, Cuffy MC, Diwan TS, Woodle SE, Abbott DE, Shah SA. Use of Elderly Allografts in Liver Transplantation. Transplantation. 2016;100:153-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Thorsen T, Aandahl EM, Bennet W, Olausson M, Ericzon BG, Nowak G, Duraj F, Isoniemi H, Rasmussen A, Karlsen TH, Foss A. Transplantation With Livers From Deceased Donors Older Than 75 Years. Transplantation. 2015;99:2534-2542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ghinolfi D, Marti J, De Simone P, Lai Q, Pezzati D, Coletti L, Tartaglia D, Catalano G, Tincani G, Carrai P, Campani D, Miccoli M, Biancofiore G, Filipponi F. Use of octogenarian donors for liver transplantation: a survival analysis. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:2062-2071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Dirican A, Soyer V, Koc S, Yagci MA, Sarici B, Onur A, Unal B, Yilmaz S. Liver Transplantation With Livers From Octogenarians and a Nonagenarian. Transplant Proc. 2015;47:1323-1325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rabelo AV, Alvarez MJ, Méndez CS, Villegas MT, MGraneroa K, Becerra A, Dominguez M, Raya AM, Exposito M, Suárez YF. Liver Transplantation Outcomes Using Grafts From Donors Older Than the Age of 80 Years. Transplant Proc. 2015;47:2645-2646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gastaca M, Guerra M, Alvarez Martinez L, Ruiz P, Ventoso A, Palomares I, Prieto M, Matarranz A, Valdivieso A, Ortiz de Urbina J. Octogenarian Donors in Liver Transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2016;48:2856-2858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Haugen CE, Bowring MG, Holscher CM, Jackson KR, Garonzik-Wang J, Cameron AM, Philosophe B, McAdams-DeMarco M, Segev DL. Survival benefit of accepting livers from deceased donors over 70 years old. Am J Transplant. 2019;19:2020-2028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Guichelaar MM, Benson JT, Malinchoc M, Krom RA, Wiesner RH, Charlton MR. Risk factors for and clinical course of non-anastomotic biliary strictures after liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:885-890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Nakamura N, Nishida S, Neff GR, Vaidya A, Levi DM, Kato T, Ruiz P, Tzakis AG, Madariaga JR. Intrahepatic biliary strictures without hepatic artery thrombosis after liver transplantation: an analysis of 1,113 liver transplantations at a single center. Transplantation. 2005;79:427-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Buis CI, Verdonk RC, Van der Jagt EJ, van der Hilst CS, Slooff MJ, Haagsma EB, Porte RJ. Nonanastomotic biliary strictures after liver transplantation, part 1: Radiological features and risk factors for early vs. late presentation. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:708-718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Heidenhain C, Pratschke J, Puhl G, Neumann U, Pascher A, Veltzke-Schlieker W, Neuhaus P. Incidence of and risk factors for ischemic-type biliary lesions following orthotopic liver transplantation. Transpl Int. 2010;23:14-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Axelrod DA, Lentine KL, Xiao H, Dzebisashvilli N, Schnitzler M, Tuttle-Newhall JE, Segev DL. National assessment of early biliary complications following liver transplantation: incidence and outcomes. Liver Transpl. 2014;20:446-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Verdonk RC, Buis CI, van der Jagt EJ, Gouw AS, Limburg AJ, Slooff MJ, Kleibeuker JH, Porte RJ, Haagsma EB. Nonanastomotic biliary strictures after liver transplantation, part 2: Management, outcome, and risk factors for disease progression. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:725-732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Senter-Zapata M, Khan AS, Subramanian T, Vachharajani N, Dageforde LA, Wellen JR, Shenoy S, Majella Doyle MB, Chapman WC. Patient and Graft Survival: Biliary Complications after Liver Transplantation. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226:484-494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Dasari BV, Mergental H, Isaac JR, Muiesan P, Mirza DF, Perera T. Systematic review and meta-analysis of liver transplantation using grafts from deceased donors aged over 70 years. Clin Transplant. 2017;31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014;12:1495-1499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3667] [Cited by in RCA: 7439] [Article Influence: 619.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 26. | Olthoff KM, Kulik L, Samstein B, Kaminski M, Abecassis M, Emond J, Shaked A, Christie JD. Validation of a current definition of early allograft dysfunction in liver transplant recipients and analysis of risk factors. Liver Transpl. 2010;16:943-949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 679] [Cited by in RCA: 932] [Article Influence: 58.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Thadhani R, Pascual M, Bonventre JV. Acute renal failure. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1448-1460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1291] [Cited by in RCA: 1169] [Article Influence: 39.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Berenguer M, Prieto M, San Juan F, Rayón JM, Martinez F, Carrasco D, Moya A, Orbis F, Mir J, Berenguer J. Contribution of donor age to the recent decrease in patient survival among HCV-infected liver transplant recipients. Hepatology. 2002;36:202-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 515] [Cited by in RCA: 494] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Jiménez-Romero C, Cambra F, Caso O, Manrique A, Calvo J, Marcacuzco A, Rioja P, Lora D, Justo I. Octogenarian liver grafts: Is their use for transplant currently justified? World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:3099-3110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 30. | Jiménez-Romero C, Justo I, Marcacuzco A, García V, Manrique A, García-Sesma Á, Calvo J, Fernández I, Martín-Arriscado C, Caso Ó. Safe use of livers from deceased donors older than 70 years in recipients with HCV cirrhosis treated with direct-action antivirals. Retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2021;91:105981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Feng S, Roberts J. An older liver in the hand, or a (possibly) younger liver in the bush? Am J Transplant. 2005;5:425-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wall WJ. Predicting outcome after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl Surg. 1999;5:458-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Lai JC, Covinsky K, Feng S. The octogenarian donor: can the liver be "younger than stated age"? Am J Transplant. 2014;14:1962-1963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Akamatsu N, Sugawara Y, Hashimoto D. Biliary reconstruction, its complications and management of biliary complications after adult liver transplantation: a systematic review of the incidence, risk factors and outcome. Transpl Int. 2011;24:379-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 275] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Westerkamp AC, Korkmaz KS, Bottema JT, Ringers J, Polak WG, van den Berg A, van Hoek B, Metselaar HJ, Porte RJ. Elderly donor liver grafts are not associated with a higher incidence of biliary complications after liver transplantation: results of a national multicenter study. Clin Transplant. 2015;29:636-643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Ghinolfi D, Lai Q, Pezzati D, De Simone P, Rreka E, Filipponi F. Use of Elderly Donors in Liver Transplantation: A Paired-match Analysis at a Single Center. Ann Surg. 2018;268:325-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Nardo B, Masetti M, Urbani L, Caraceni P, Montalti R, Filipponi F, Mosca F, Martinelli G, Bernardi M, Daniele Pinna A, Cavallari A. Liver transplantation from donors aged 80 years and over: pushing the limit. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:1139-1147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Ghinolfi D, De Simone P, Lai Q, Pezzati D, Coletti L, Balzano E, Arenga G, Carrai P, Grande G, Pollina L, Campani D, Biancofiore G, Filipponi F. Risk analysis of ischemic-type biliary lesions after liver transplant using octogenarian donors. Liver Transpl. 2016;22:588-598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Ghinolfi D, Tincani G, Rreka E, Roffi N, Coletti L, Balzano E, Catalano G, Meli S, Carrai P, Petruccelli S, Biancofiore G, Filipponi F, De Simone P. Dual aortic and portal perfusion at procurement prevents ischaemic-type biliary lesions in liver transplantation when using octogenarian donors: a retrospective cohort study. Transpl Int. 2019;32:193-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Gastaca M, Valdivieso A, Pijoan J, Errazti G, Hernandez M, Gonzalez J, Fernandez J, Matarranz A, Montejo M, Ventoso A, Martinez G, Fernandez M, de Urbina JO. Donors older than 70 years in liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:3851-3854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Alamo JM, Olivares C, Jiménez G, Bernal C, Marín LM, Tinoco J, Suárez G, Serrano J, Padillo J, Gómez MÁ. Donor characteristics that are associated with survival in liver transplant recipients older than 70 years with grafts. Transplant Proc. 2013;45:3633-3636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Jiménez-Romero C, Manrique A, García-Conde M, Nutu A, Calvo J, Caso Ó, Marcacuzco A, García-Sesma Á, Álvaro E, Villar R, Aguado JM, Conde M, Justo I. Biliary Complications After Liver Transplantation From Uncontrolled Donors After Circulatory Death: Incidence, Management, and Outcome. Liver Transpl. 2020;26:80-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Sundaram V, Jones DT, Shah NH, de Vera ME, Fontes P, Marsh JW, Humar A, Ahmad J. Posttransplant biliary complications in the pre- and post-model for end-stage liver disease era. Liver Transpl. 2011;17:428-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Seehofer D, Eurich D, Veltzke-Schlieker W, Neuhaus P. Biliary complications after liver transplantation: old problems and new challenges. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:253-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Baccarani U, Isola M, Adani GL, Avellini C, Lorenzin D, Rossetto A, Currò G, Comuzzi C, Toniutto P, Risaliti A, Soldano F, Bresadola V, De Anna D, Bresadola F. Steatosis of the hepatic graft as a risk factor for post-transplant biliary complications. Clin Transplant. 2010;24:631-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Bachar GN, Cohen M, Belenky A, Atar E, Gideon S. Effect of aging on the adult extrahepatic bile duct: a sonographic study. J Ultrasound Med. 2003;22:879-82; quiz 883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | López-Andújar R, Orón EM, Carregnato AF, Suárez FV, Herraiz AM, Rodríguez FS, Carbó JJ, Ibars EP, Sos JE, Suárez AR, Castillo MP, Pallardó JM, De Juan Burgueño M. T-tube or no T-tube in cadaveric orthotopic liver transplantation: the eternal dilemma: results of a prospective and randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2013;258:21-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Scatton O, Meunier B, Cherqui D, Boillot O, Sauvanet A, Boudjema K, Launois B, Fagniez PL, Belghiti J, Wolff P, Houssin D, Soubrane O. Randomized trial of choledochocholedochostomy with or without a T tube in orthotopic liver transplantation. Ann Surg. 2001;233:432-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Sharma S, Gurakar A, Jabbour N. Biliary strictures following liver transplantation: past, present and preventive strategies. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:759-769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 263] [Cited by in RCA: 282] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 50. | Taner CB, Bulatao IG, Willingham DL, Perry DK, Sibulesky L, Pungpapong S, Aranda-Michel J, Keaveny AP, Kramer DJ, Nguyen JH. Events in procurement as risk factors for ischemic cholangiopathy in liver transplantation using donation after cardiac death donors. Liver Transpl. 2012;18:100-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Asociacion Española de Cirujanos; Sociedad Española de Trasplante; Sociedad Española de Trasplante Hepático; and The Transplantation Society.

Specialty type: Transplantation

Country/Territory of origin: Spain

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Costache RS, Romania; Dabbous H, Egypt S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang YL