Published online Feb 15, 2026. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v17.i2.114252

Revised: October 11, 2025

Accepted: December 16, 2025

Published online: February 15, 2026

Processing time: 144 Days and 22 Hours

This study elucidates the mechanisms through which electroacupuncture (EA) at Zusanli acupoint, applied at different frequencies, alleviates diabetic gastroparesis (DGP). The modulation of the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS)-stimulator of interferon genes (STING) pathway, its regulation of M2 macrophage pyroptosis, and the consequent protection of interstitial cells of Cajal (ICCs) were investigated.

To investigate the mechanism by which EA alleviates DGP.

A DGP rat model was induced by feeding a high-fat/high-sucrose diet combined with a single intraperitoneal injection of streptozotocin (30 mg/kg). Rats suc

The results of this study revealed that HEA significantly increased gastric emptying [0.69 (0.55, 0.72) vs DGP 0.44 (0.26, 0.48), P < 0.05] and reduced whole gut transit time (361.34 ± 10.51 vs DGP 537.33 ± 100.57, P < 0.01), with improved efficacy compared to LEA. In DGP rats, ICC counts were significantly reduced, transferase dUTP nick-end labeling-positive apoptotic markers were elevated, and CD206+ cells were diminished; these alterations were reversed mainly by EA, with HEA showing the greatest effect. Expression of cGAS-STING signaling components and pyroptosis-related proteins (Gasdermin D, NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3, caspase-1), along with secretion of IL-1β and IL-18, were significantly up-regulated in the DGP group. HEA significantly suppressed cGAS pathway activation, reduced pyroptosis-associated proteins and inflammatory mediators, and outperformed LEA (P < 0.05).

HEA ameliorates gastric dysmotility in DGP by suppressing the cGAS-STING pathway, attenuating M2 macrophage pyroptosis and inflammatory responses, and preserving ICC networks. These findings identify a novel EA/cGAS-STING/pyroptosis axis and highlight its therapeutic potential as a mechanistic target for optimizing DGP treatment strategies.

Core Tip: For the first time we show that high-frequency electroacupuncture at Zusanli acupoint outperforms low-frequency stimulation in diabetic gastroparesis by simultaneously blocking the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase-stimulator of interferon genes pathway, halting M2-macrophage pyroptosis, curtailing interleukin-1β/interleukin-18 release and thereby rescuing the interstitial cells of Cajal network, offering an immediately translatable, non-drug strategy to restore gastric motility.

- Citation: Fan MW, Tian JL, Zhang SH, Zhao ZJ, Liu XR, Liu CX, Chen Y. Electroacupuncture protects gastric Cajal cells by reducing macrophage pyroptosis in diabetic gastroparesis. World J Diabetes 2026; 17(2): 114252

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v17/i2/114252.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v17.i2.114252

Diabetic gastroparesis (DGP) is a frequent and severe complication of diabetes mellitus, characterized by delayed gastric emptying in the absence of mechanical obstruction[1,2]. Its prevalence is reported to reach 40%-47% in patients with type I diabetes and 32%-47% in those with type II diabetes[3]. DGP presents with symptoms such as early satiety, postprandial fullness, nausea, vomiting, and appetite loss. These manifestations not only impair patients’ quality of life but also contribute to uncontrolled fluctuations in blood glucose, accelerating the onset and progression of other diabetic complications[4,5]. Despite its high clinical burden, the pathogenesis of DGP remains incompletely understood, underscoring the importance of exploring its underlying mechanisms to develop effective therapeutic strategies.

Electroacupuncture (EA), which integrates traditional acupuncture with modern electrical stimulation, has demonstrated beneficial effects in modulating gastrointestinal motility disorders[6]. Previous studies have shown that EA stimulation at the Zusanli acupoint (ST36) improves both glucose metabolism disturbances and gastric dysmotility in type II diabetes mellitus models. EA was found to restore the morphology, quantity, and c-kit expression of intestinal mesenchymal stromal cells, ameliorating neurogenic dysfunction of colonic transit[7]. Stimulation at a specific frequency of 100 Hz has been reported to be particularly effective in increasing gastrointestinal motility[8]. Our previous work has shown that EA at ST36 promotes the survival of gastric sinus interstitial cells of Cajal (ICCs) and alleviates delayed gastric emptying in diabetic rats[9]. However, the molecular and immunological mechanisms underlying EA-mediated ICC repair remain poorly defined.

ICCs function as pacemaker cells in the gastrointestinal tract by generating slow waves that propagate to smooth muscle cells, regulate smooth muscle contractility, and transmit neural signals[10]. A reduction or loss of ICCs has been strongly implicated in the pathogenesis of DGP[11]. In diabetic animal models, delayed gastric emptying, impaired electrical pacing, and reduced neurotransmission are consistently associated with decreased ICC numbers and structural damage, highlighting their central role in disease progression[12-14]. Our previous findings showed increased apoptosis of ICCs in the gastric sinus of diabetic rats, coupled with delayed gastric emptying and disrupted gastric contractions, further implicating ICC apoptosis as a critical pathological mechanism in DGP.

The gastrointestinal lamina propria harbors a large population of macrophages, existing in both proinflammatory (M1) and anti-inflammatory/restorative (M2) states[15-17]. Macrophages in the gastric lamina propria are located adjacent to ICCs and enteric neurons[18]. Evidence from Csf1op/op diabetic mice, which lack macrophages, demonstrated that macrophage depletion prevents gastrointestinal dysmotility, suggesting macrophages are a pivotal immune population in sustaining the chronic inflammatory state of DGP tissues and may be essential regulators of ICC homeostasis[19]. In DGP models, delayed gastric emptying and increased ICC apoptosis have been associated with a significant reduction in M2 macrophages, accompanied by elevated levels of the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18[20-22]. Thus, a decline in M2 macrophages may represent a fundamental mechanism driving chronic metabolic inflammation and ICC injury in DGP.

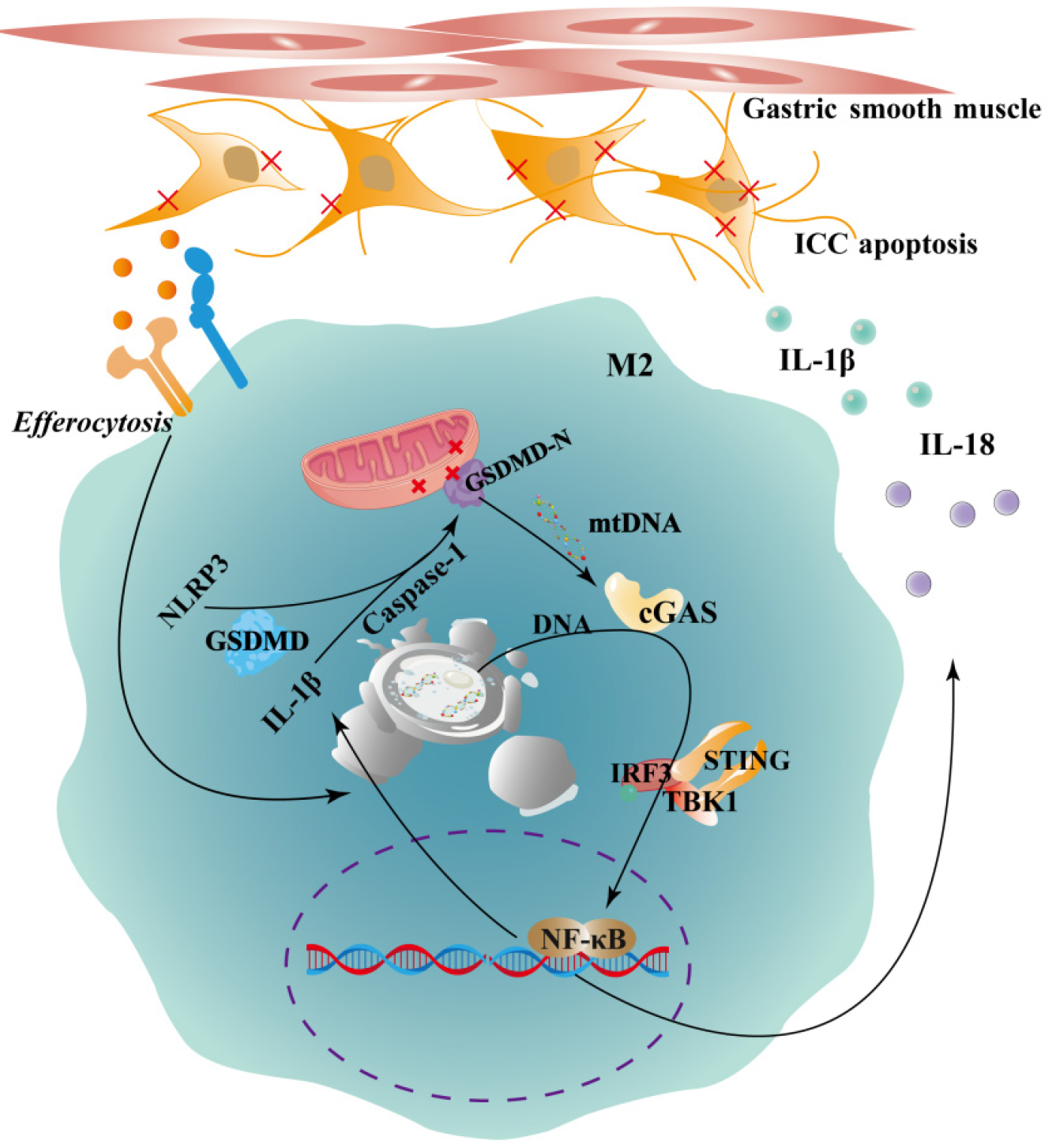

M2 macrophages play a protective role by phagocytosing apoptotic ICCs[23]. This process supports tissue homeostasis under physiological conditions and limits inflammation by releasing anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-10 and transforming growth factor-β[24,25]. Macrophage phagocytic function is closely associated with their pyroptotic state[26-28]. In the chronic inflammatory milieu of DGP, reduced M2 macrophage numbers and impaired function may hinder the clearance of apoptotic ICCs, promoting persistent tissue injury. Central to this process is the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS)-stimulator of interferon genes (STING) signaling pathway, a critical mediator of macrophage pyroptosis[29-31]. Inefficient clearance of cytosolic DNA fragments from apoptotic cells may activate cGAS, a cytosolic DNA sensor, which catalyzes the synthesis of cyclic GMP-AMP. Cyclic GMP-AMP then binds to and activates STING, triggering downstream signaling cascades involving TANK-binding kinase 1 and interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3), ultimately inducing the production of type I interferons and proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and IL-18[32,33]. Hyperactivation of the Cgas-STING pathway is therefore a key driver of macrophage pyroptosis[34]. Pyroptosis is a lytic form of programmed cell death mediated by the Gasdermin D protein (GSDMD), which forms plasma membrane pores, resulting in mitochondrial damage, cellular swelling, and rupture, ultimately impairing macrophage function[35,36].

Based on these findings, we hypothesize that aberrant activation of the cGAS-STING pathway in DGP drives pyroptosis of M2 macrophages, depleting protective macrophage subsets, amplifying inflammatory cytokine release, exacerbating ICC dysfunction, and worsening gastric motility impairment (Figure 1). This study aims to elucidate the immunoinflammatory and programmed cell death mechanisms underlying the therapeutic effects of EA in DGP. By focusing on the macrophage cGAS-STING-pyroptosis axis, our work provides experimental and theoretical evidence for optimizing EA parameters and developing novel therapeutic strategies for DGP.

Thirty male Sprague-Dawley rats, aged 4-5 weeks and weighing 180-200 g, were obtained from Jinan Pengyue Laboratory Animal Breeding Co. The animals were maintained under controlled laboratory conditions, with a 12-hour light/dark cycle, relative humidity of 50%-60%, and ambient temperature of 20-24 °C. All experimental procedures were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Binzhou Medical College.

After a one-week acclimatization period, all rats were labeled and randomly assigned into two groups: A normal control group (n = 6) and a DGP model group (n = 24). The DGP model in Sprague-Dawley rats was established using a modified protocol based on a previous study[37]. Rats in the model group were fed a high-fat, high-glucose diet for 8 weeks, followed by a single intraperitoneal injection of streptozotocin (30 mg/kg). Control rats received an equivalent intraperitoneal injection of citrate-sodium citrate buffer. One week after streptozotocin administration, whole blood samples were collected from the tail vein at multiple time points to measure blood glucose levels. Successful induction of diabetes mellitus was confirmed when blood glucose levels were ≥ 16.7 mmol/L.

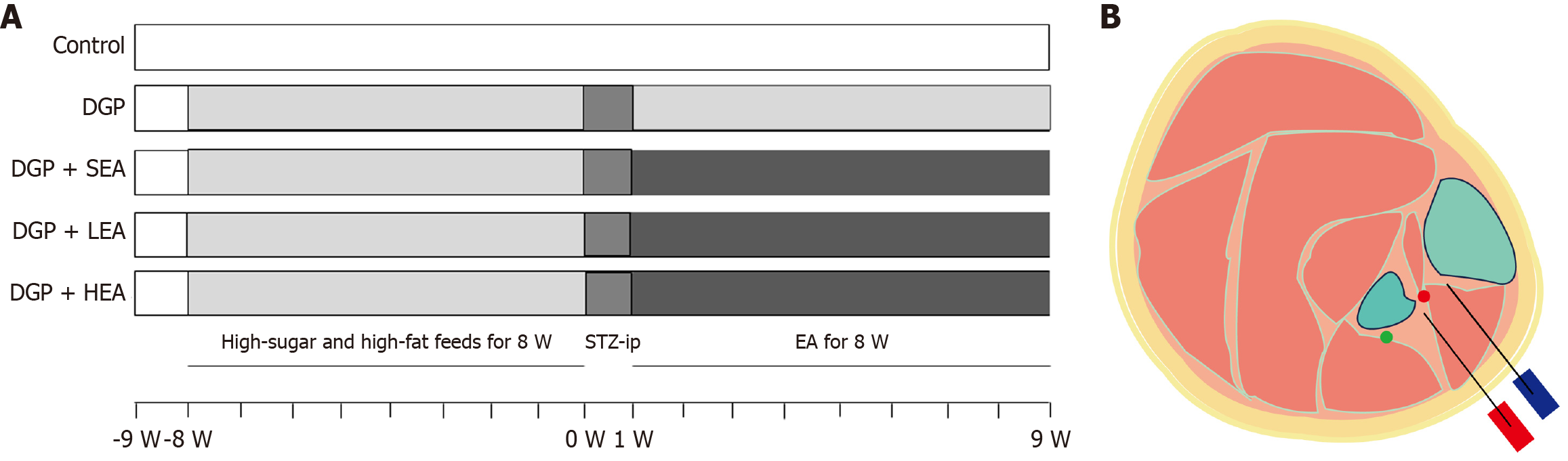

Following successful model establishment, the DGP rats were randomly assigned into four groups (n = 6 per group): The DGP group, the DGP + sham-EA group (SEA; needling only without electrical stimulation, 0 Hz/0 mA), the DGP + low-frequency EA group (LEA; 10 Hz, 1-3 mA), and the DGP + high-frequency EA group (HEA; 100 Hz, 1-3 mA). EA treatment was administered once daily at 9:00 am for 30 minutes over 8 weeks (Figure 2A). The ST36 was selected as the treatment site (Figure 2B), and stimulation was delivered using an external pulse generator (YC3-20285, Chengdu Instrument Factory, Chengdu, China). Insert an acupuncture needle into the skin at ST36 to a depth of 5 mm. Apply intermittent unidirectional square pulses via an external pulse generator with the following parameters: Pulse width 0.5 milliseconds; duration 0.1 milliseconds “on” and 0.4 milliseconds “off”[38]. The overall experimental procedure is illustrated in Figure 1.

After a 24-hour fasting period, each rat was administered 0.3 mL of phenol red solution via gavage, and the exact time of administration was recorded. Five hours later, the fecal color was monitored at 10-minute intervals. To improve color visualization, 0.1 mmol/L NaOH solution was added, and the time at which pink-colored feces first appeared was noted. The total gastrointestinal transit time was calculated as the interval between the time of gavage and the discharge of pink feces. The researcher performing the whole gut transit time (WGTT) measurement and data recording was blinded to the group allocation of the rats.

Approximately 100 mg of fresh or frozen gastric tissue was accurately weighed, homogenized in lysis buffer, and centrifuged to obtain the supernatant. Protein concentration was determined using the bicinchoninic acid assay. The supernatant was then mixed with 5 × sampling buffer at a ratio of 4:1, heated in a metal bath for 10 minutes, and stored at -80 °C until use. Target proteins were separated by sodium-dodecyl sulfate gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes, which were then blocked with 5% skim milk at room temperature for 2 hours. Membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies (Table 1). The following day, they were washed three times with Tris-buffered saline with Tween and subsequently incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 hour. Protein bands were visualized using a gel imaging system. The quantification of band intensity was carried out in a blinded manner with respect to the sample groups. Quantitative density analysis: ImageJ software was used to analyze the optical density values of target bands and internal control bands. First, a rectangular region of equal size was manually or automatically delineated for each band, and its integrated optical density value was recorded. Subsequently, the optical density value of the target protein was divided by that of its corresponding internal control protein to obtain the relative expression level for that sample.

| Antibody | Dilution | Host | Source, catalogue number |

| Primary antibodies | |||

| c-kit | 1:700 | Rabbit | Zenbio, 347321 |

| TUNEL | 1:1000 | Rabbit | Boster, MK1018 |

| GSDMD | 1:1000 | Rabbit | Boster, A02842 |

| NLRP3 | 1:1000 | Rabbit | Boster, BA3677 |

| Caspase-1 | 1:700 | Rabbit | Boster, M00048-2 |

| IL-1β | 1:1000 | Rabbit | Boster, BA14789 |

| IL-18 | 1:1000 | Rabbit | Affinity, PB0058 |

| cGAS | 1:2000 | Mouse | Boster, A31676-1 |

| STING | 1:700 | Rabbit | Boster, PB9513 |

| p-STING | 1:100 | Rabbit | Boster, BM5485 |

| CD206 | 1:100 | Rabbit | Boster, DF4149 |

| IRF3 | 1:100 | Rabbit | Boster, A00165-7 |

| p-IRF3 | 1:100 | Rabbit | Boster, A00165-7 |

| GAPDH | 1:10000 | Mouse | Boster, BM1623 |

| β-actin | 1:100000 | Rabbit | ABclonal, AC026 |

| Secondary antibodies | |||

| CY3 Conjugated AffiniPure | 1:200 | Goat | Boster, BA1032 |

| FITC Conjugated AffiniPure | 1:60 | Rabbit | Boster, BA1108 |

Fresh gastric sinus tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at a thickness of 5 μm. Following deparaffinization, sections underwent antigen retrieval and endogenous peroxidase blocking, after which they were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin for 30 minutes. Sections were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies. The next day, after thorough washing, sections were incubated with secondary antibodies at 20 °C for 1 hour. Staining was performed using 3,3’-diaminobenzidine and hematoxylin, followed by dehydration, clearing, and mounting with neutral resin. Finally, the sections were examined under a microscope for analysis. The acquisition of immunofluorescence images and subsequent quantitative analysis were performed by investigators who were blinded to the experimental groups.

Tissue sections were processed following the same protocol as immunohistochemistry. Monoclonal primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4 °C. The following day, after washing, sections were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate- and Cy3-conjugated secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 hour in the dark. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI antifluorescence quencher, and images were immediately captured and analyzed using a fluorescence microscope after the final wash. Image acquisition and quantitative analysis: All sections were numbered prior to image acquisition. A researcher unaware of experimental group assignments performed image acquisition using a fluorescence microscope. At least three non-overlapping fields of view were selected for imaging. Images were quantitatively analyzed using ImageJ software. Positive signal areas were identified by applying a uniform threshold. The fluorescent area of specific markers within each field of view was calculated and normalized against the total DAPI-stained area. Final results represented the average across all fields of view for each sample.

SPSS 24.0 software was utilized for statistical analysis, while GraphPad Prism 8 was used for creating graphs. Data are presented as mean ± SD. After verifying assumptions (normality by Shapiro-Wilk test; homogeneity of variances by Levene’s test), inter-group comparisons were made. For two-group comparisons, the independent samples t-test (with Cohen’s d as effect size) or the Mann-Whitney U test was applied for normally or non-normally distributed data, respectively. Multi-group comparisons across control, HEA, LEA groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA (with η2 as effect size), followed by Bonferroni-corrected post-hoc tests for the pre-planned comparisons of each intervention group against the control. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Correlation analysis used Pearson’s correlation coefficient and linear regression, with R2 and P < 0.05 indicating significance.

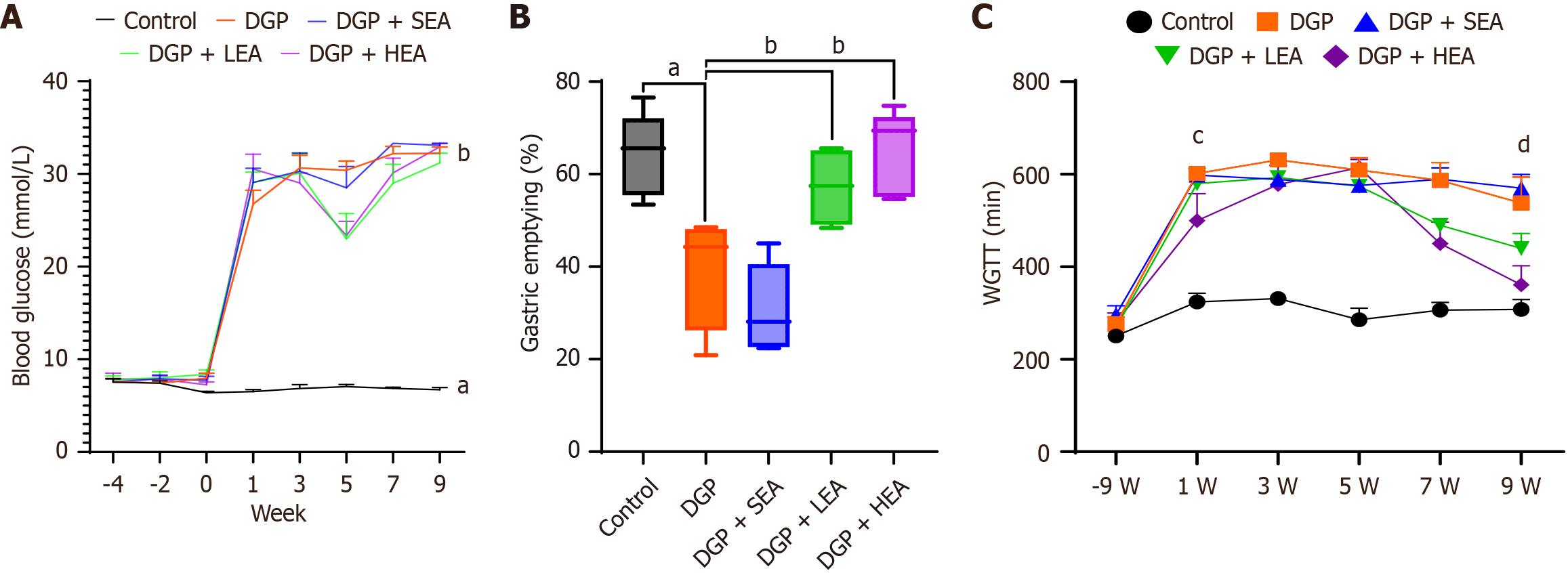

Before modeling (9 weeks), no significant differences were observed in blood glucose levels between the DGP group (8.24 ± 1.63 mmol/L) and the control group (8.01 ± 1.44 mmol/L, P > 0.05). Similarly, WGTT values showed no significant difference between the DGP group (250.67 ± 21.58 minutes) and the control group (275.33 ± 40.04 minutes, P > 0.05).

At 1-week post-modeling, blood glucose levels in the DGP group (31.54 ± 2.55 mmol/L) were significantly higher than in the control group (8.25 ± 1.96 mmol/L, aP < 0.05). WGTT was also significantly prolonged in the DGP group (601.84 ± 22.56 minutes) compared with the control group (325.33 ± 40.05 minutes, P < 0.05), confirming successful establishment of the DGP model. After 4 weeks of EA intervention (week 5), blood glucose levels showed no significant difference between the SEA group (30.12 ± 3.45 mmol/L) and the DGP group (28.78 ± 5.67 mmol/L, P > 0.05). However, both the LEA group (22.56 ± 3.18 mmol/L) and the HEA group (23.56 ± 4.67 mmol/L) demonstrated significant reductions compared with the DGP group (P < 0.05 for both). WGTT values showed no significant differences among the DGP (609.15 ± 65.19 minutes), SEA (575.83 ± 36.56 minutes), LEA (573.87 ± 67.89 minutes), and HEA (641.94 ± 43.15 minutes) groups (all P > 0.05).

Following 8 weeks of intervention, blood glucose levels did not differ significantly among the DGP (32.67 ± 2.34 mmol/L), SEA (28.56 ± 6.78 mmol/L), LEA (28.45 ± 3.55 mmol/L), and HEA (28.56 ± 4.12 mmol/L) groups (all P > 0.05). However, WGTT showed significant improvements: While the SEA group (569.67 ± 73.68 minutes) did not differ from the DGP group (537.33 ± 100.57 minutes, P > 0.05), the LEA group (439.56 ± 33.15 minutes) showed a significant reduction compared with DGP (P < 0.05). The HEA group (361.34 ± 10.51 minutes) showed an even greater reduction compared with both the DGP group and the LEA group (P < 0.01). Furthermore, WGTT in the HEA group at 8 weeks was significantly shorter compared to its own 4-week value (P < 0.05). Assessment of gastric emptying rates (%) at the endpoint revealed significantly lower values in the DGP group 44% (26%, 48%) and SEA group 28% (23%, 41%) compared with the control group [66% (55%, 72%), P < 0.05]. The LEA group 51% (46%, 65%) and HEA group 69% (55%, 72%) displayed significantly higher gastric emptying rates compared with the DGP group (all P < 0.05, Figure 3).

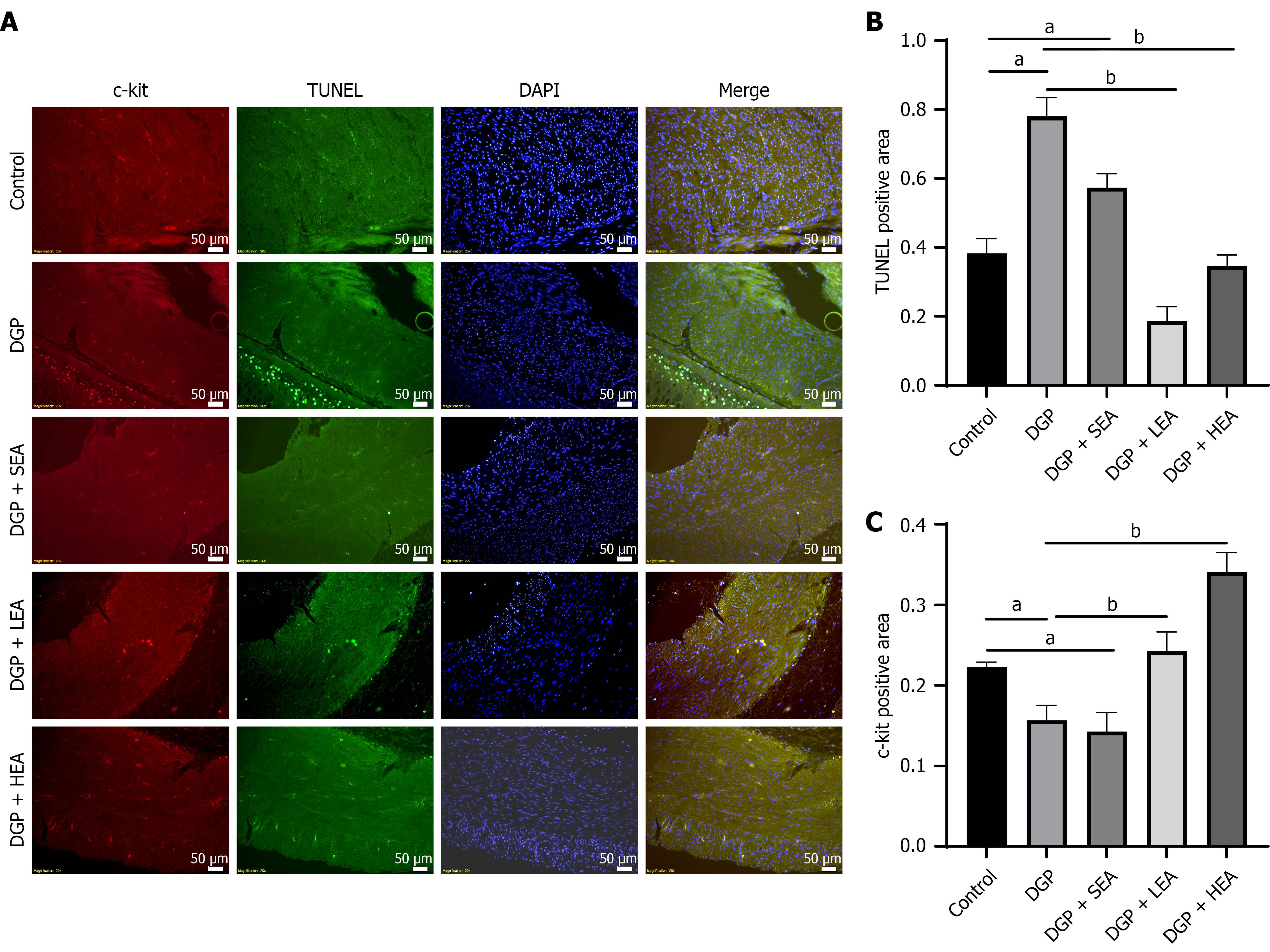

After 8 weeks of modeling and intervention, the rats were sacrificed, and their gastric antrum tissues were collected. Immunofluorescence analysis revealed that the mean fluorescence area (%) of c-kit-labeled ICCs was significantly reduced in the DGP group (0.15 ± 0.05) compared with the control group (0.22 ± 0.56, P < 0.05, Cohen’s d = 0.89). Both the LEA group (0.25 ± 0.04) and the HEA group (0.28 ± 0.13) showed significant increases in c-kit fluorescence compared with the DGP group (all P < 0.05, η2 = 1.43). Transferase dUTP nick-end labeling labeling of apoptotic cells in the gastric muscularis propria demonstrated an opposite pattern. The mean fluorescence area (%) was significantly higher in the DGP group (0.79 ± 0.11) compared with the control group (0.38 ± 0.21, P < 0.05, Cohen’s d = 1.21). Both the LEA group (0.22 ± 0.34) and the HEA group (0.38 ± 0.23) displayed significantly lower transferase dUTP nick-end labeling fluorescence than the DGP group (P < 0.05, η2 = 0.87, Figure 4).

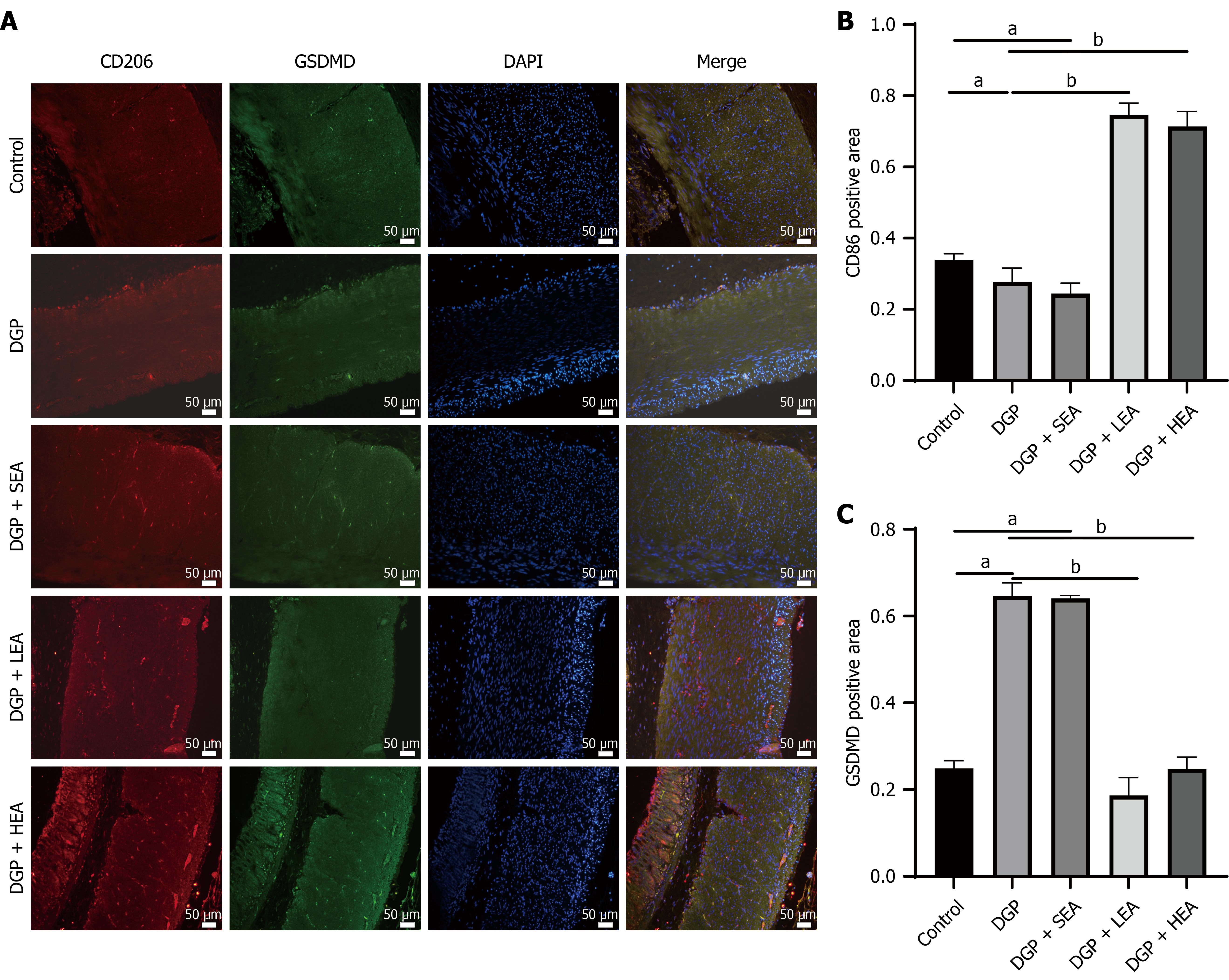

Immunofluorescence analysis of rat gastric sinus tissue showed that the mean fluorescence area (%) of CD206+ M2 macrophages was significantly lower in the DGP group (0.31 ± 0.34) compared with the control group (0.38 ± 0.33, P < 0.05, Cohen’s d = 1.02). Both the LEA group (0.35 ± 0.32) and the HEA group (0.38 ± 0.43) displayed significantly higher levels of CD206+ M2 macrophages than the DGP group (P < 0.05, η2 = 0.81).

Meanwhile, immunofluorescence detection of the pyroptosis-related protein GSDMD in the gastric muscular layer revealed a significantly higher fluorescence area in the DGP group (0.78 ± 0.21) compared with the control group (0.34 ± 0.11, P < 0.05, Cohen’s d = 1.19). This increase was reversed in both the LEA group (0.32 ± 0.22) and the HEA group (0.21 ± 0.25), which showed significantly reduced GSDMD expression compared with the DGP group (P < 0.05, η2 = 0.93, Figure 5).

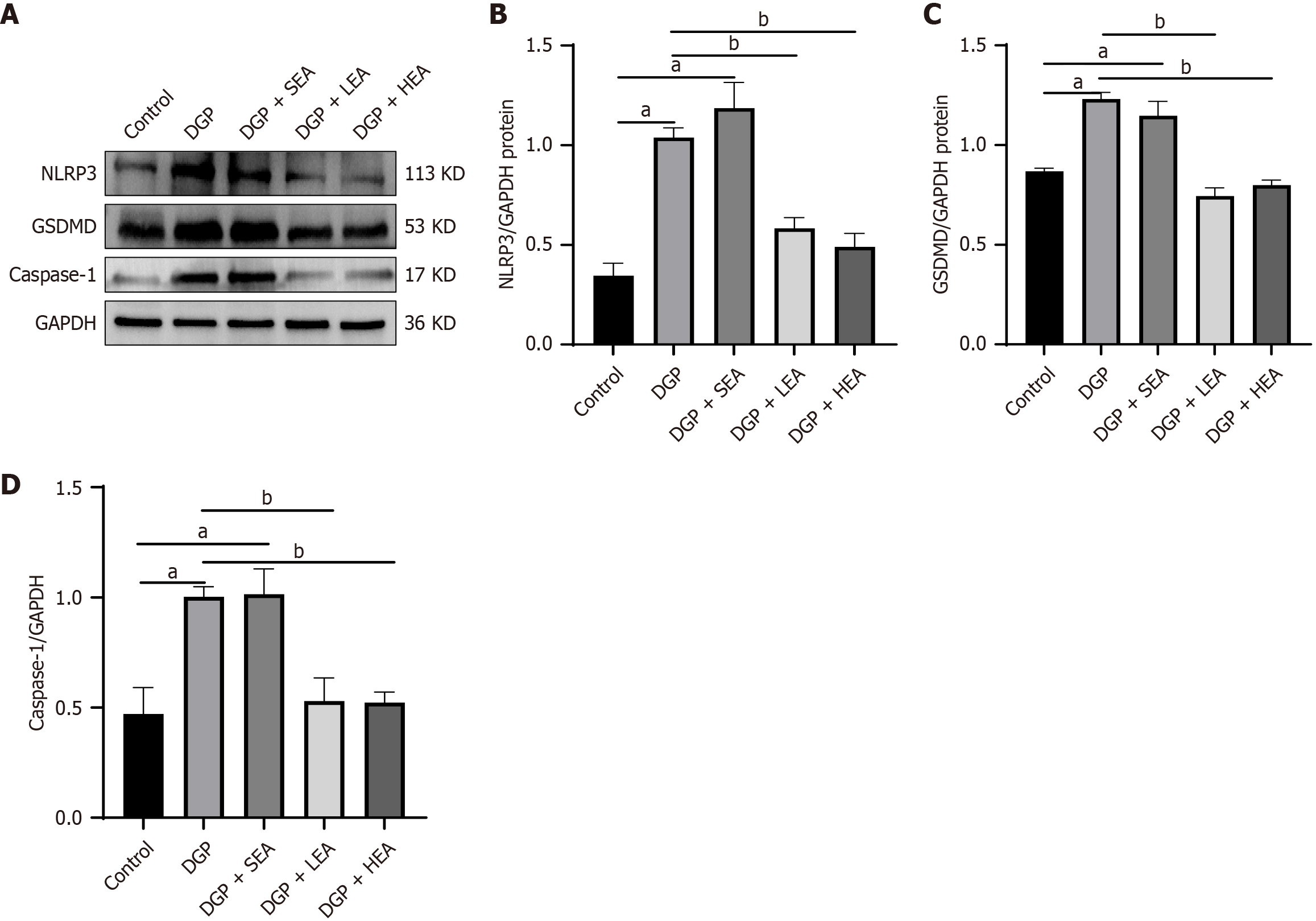

Similarly, expression of GSDMD-related pyroptotic pathway proteins, including NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) and caspase-1, was elevated in the DGP group compared with the control group (P < 0.05, NLRP3: Cohen’s d = 2.79; caspase-1: Cohen’s d = 1.31). In comparison, both the LEA and HEA groups demonstrated significantly lower expression of these proteins than the DGP group (all P < 0.05, NLRP3: η2 = 0.84, caspase-1: η2 = 0.70, Figure 6).

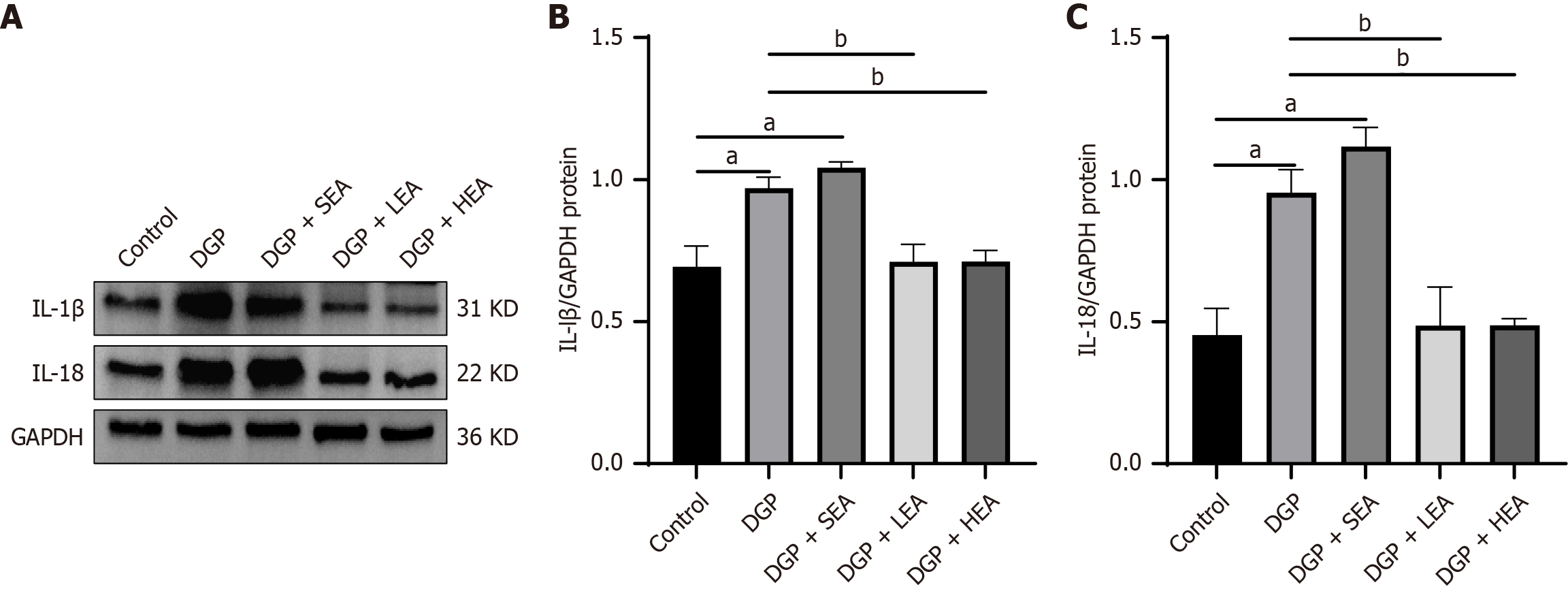

Moreover, levels of the inflammatory mediators IL-1β and IL-18 were significantly increased in the DGP group compared with the control group (IL-1β: 0.99 ± 0.31 vs 0.57 ± 0.11, Cohen’s d = 1.04; IL-18: 0.89 ± 0.35 vs 0.40 ± 0.21, Cohen’s d = 1.73; both P < 0.05). Both cytokines were significantly reduced in the LEA group (IL-1β: 0.76 ± 0.32; IL-18: 0.54 ± 0.22) and the HEA group (IL-1β: 0.69 ± 0.27, η2 = 0.38; IL-18: 0.43 ± 0.37, η2 = 0.72) relative to the DGP group (P < 0.05, Figure 7).

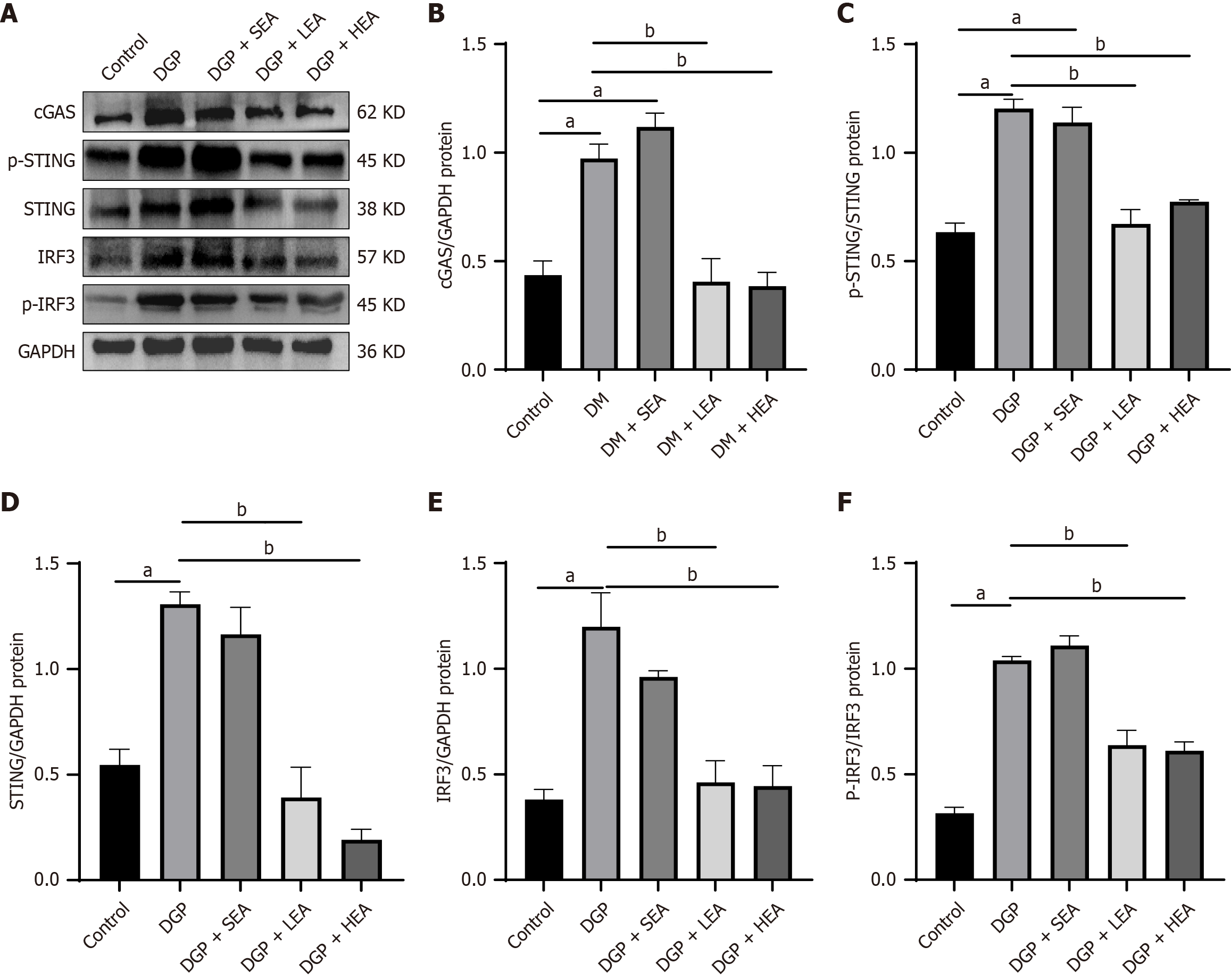

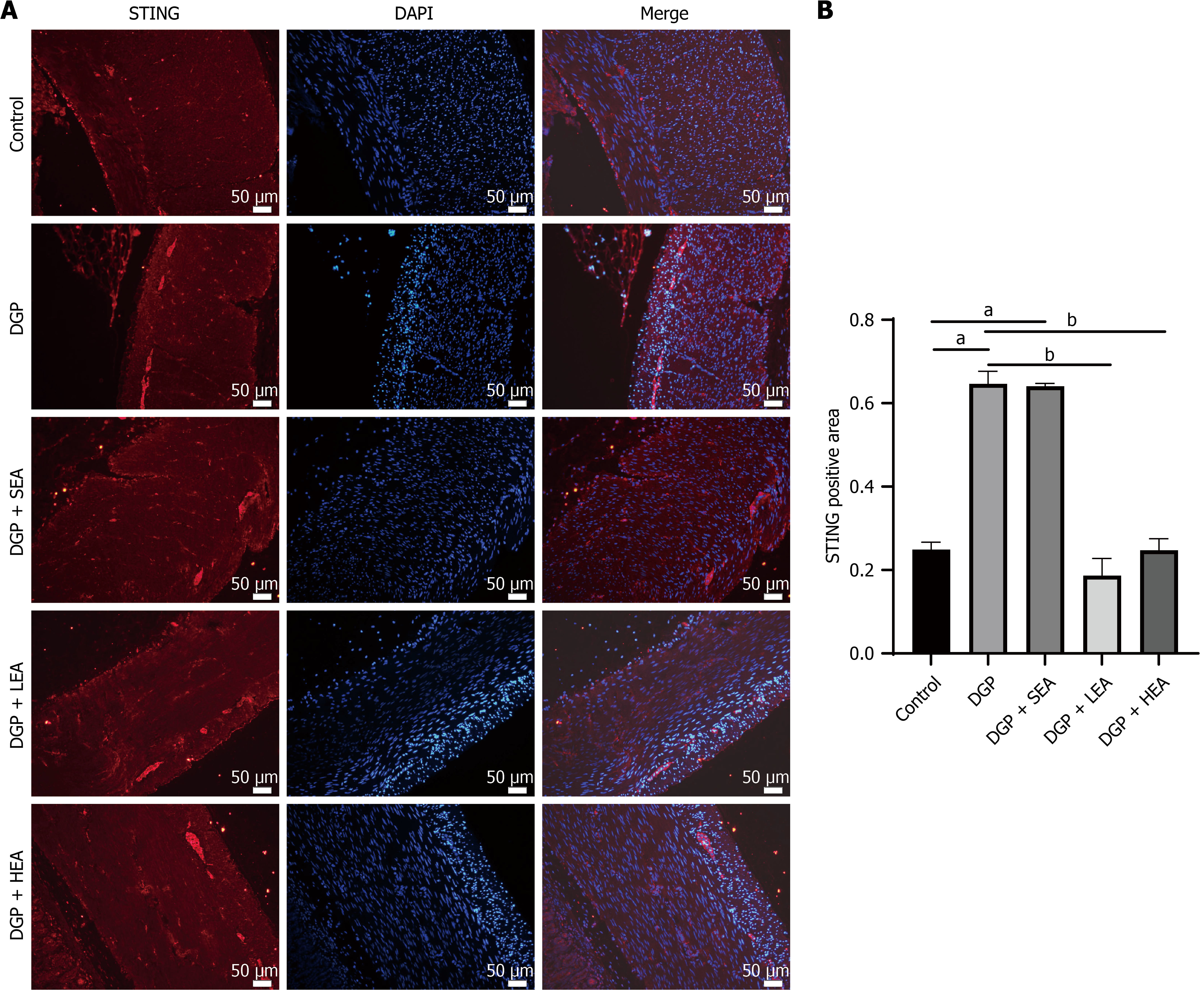

The expression of cGAS-STING pathway-related proteins, including cGAS, STING, p-STING/STING, IRF3, and p-IRF3/IRF3, was significantly higher in both the DGP and SEA groups compared with the control group (all P < 0.05, cGAS: Cohen’s d = 1.24; STING: Cohen’s d = 1.35; p-STING/STING: Cohen’s d = 1.99; IRF3: Cohen’s d = 0.64; p-IRF3/IRF3: Cohen’s d = 1.34). In comparison, their expression was significantly reduced in the LEA and HEA groups relative to the DGP group (all P < 0.05, cGAS: η2 = 0.15; STING: η2 = 0.64; p-STING/STING: η2 = 0.88; IRF3: η2 = 0.94; p-IRF3/IRF3: η2 = 1.10, Figure 8). Similarly, immunofluorescence analysis of the gastric mucosal muscular layer demonstrated that STING expression was significantly elevated in the DGP and SEA groups compared with the Control group (all P < 0.05, Cohen’s d = 1.55). In comparison, both the LEA and HEA groups showed significantly lower STING expression compared to the DGP group (all P < 0.05, η2 = 0.71, Figure 9).

In this study, we successfully established a rat model of DGP, characterized by hyperglycemia, delayed gastric emptying, prolonged gastrointestinal transit, reduced numbers of ICCs, and increased apoptosis. The EA treatment, particularly at a high frequency of 100 Hz, significantly improved gastric emptying, shortened gastrointestinal transit time, increased the number of ICCs, and reduced ICC apoptosis. In the gastric lamina propria muscle layer of DGP rats, the number of M2 macrophages was significantly decreased, accompanied by upregulation of GSDMD and its upstream regulators NLRP3 and caspase-1, along with increased secretion of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18. Moreover, activation of the cGAS-STING signaling pathway was evident in the DGP state, as demonstrated by elevated expression of cGAS, STING, p-STING, IRF3, and p-IRF3 proteins. Moreover, the HEA effectively suppressed this aberrant pathway activation, reducing M2 macrophage pyroptosis and lowering proinflammatory cytokine levels.

These results suggest that EA stimulation at ST36, particularly with high-frequency parameters, ameliorates DGP by modulating immunoinflammatory responses and programmed cell death. This protective effect likely occurs through inhibition of cGAS-STING pathway overactivation, attenuation of M2 macrophage pyroptosis, preservation of ICC networks, and restoration of gastric motility. The findings of this study strongly support our initial hypothesis that pyroptosis-induced phagocytic insufficiency activates the cGAS-STING pathway, amplifying inflammation and aggravating ICC injury. In the chronic hyperglycemic and proinflammatory microenvironment characteristic of DGP, ICCs undergo apoptosis. Under physiological conditions, M2 macrophages phagocytose apoptotic ICC debris, maintain tissue homeostasis, and secrete anti-inflammatory mediators. However, in the present study, the reduced CD206+ fluorescence area indicated a significant decline in M2 macrophage numbers, suggesting impaired phagocytic capacity during DGP. As a result, apoptotic ICC-derived DNA fragments that were not efficiently cleared likely acted as activators of cGAS.

Our results further confirmed overactivation of the cGAS-STING pathway in the gastric tissues of DGP rats. Once activated, this pathway not only facilitated the release of proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 but also served as a critical driver of macrophage pyroptosis. Similarly, we observed significant upregulation of the pyroptosis execution protein GSDMD and its upstream regulators, NLRP3 and caspase-1, in the gastric myenteric layer under DGP conditions, accompanied by elevated local levels of IL-1β and IL-18. These findings indirectly confirm that pyroptosis occurs within M2 macrophages.

Functionally, M2 macrophage pyroptosis contributes to disease progression through dual mechanisms. First, it further depletes an already diminished pool of macrophages with reparative and anti-inflammatory roles. Second, pyroptotic rupture leads to the uncontrolled release of proinflammatory mediators, intensifying local inflammation and promoting the further apoptosis of adjacent ICCs. These processes establish a vicious cycle that disrupts ICC networks and leads to gastric motility impairment.

This study further confirmed the therapeutic efficacy of EA stimulation, particularly HEA at 100 Hz, in alleviating DGP. EA effectively suppressed activation of the cGAS-STING pathway and inhibited GSDMD-mediated pyroptotic death of M2 macrophages. Both western blot and immunofluorescence analyses consistently demonstrated that LEA and HEA significantly downregulated the expression of key proteins in the cGAS-STING pathway, including cGAS, STING, p-STING, IRF3, and p-IRF3. Inhibition of this pathway was accompanied by a significant reduction in pyroptosis-related markers, including GSDMD, NLRP3, and caspase-1, as well as the restoration of M2 macrophage numbers and a concomitant decrease in the release of proinflammatory cytokines. By modulating macrophage chemotaxis and inflammatory status, EA resulted in a more favorable local microenvironment for ICC survival and functional recovery, as evidenced by increased ICC numbers, reduced apoptosis, and significant improvements in gastric motility indices.

Moreover, HEA demonstrated superior efficacy compared with LEA in suppressing cGAS-STING activation (Figures 8 and 9), attenuating pyroptosis (Figures 5 and 6), lowering proinflammatory cytokine levels (Figure 7), and improving gastrointestinal transport function (WGTT, Figure 3). These results are consistent with previous evidence suggesting that 100 Hz EA is particularly effective in increasing gastrointestinal motility. The differential effects of stimulation frequency may be attributed to the selective activation of distinct afferent nerve fiber subtypes (e.g., Aβ, Aδ, and C fibers) innervating the ST36 acupoint. Electrical activation of these fibers at specific frequencies could modulate vagal activity and neuro-immune interactions through spinal and supraspinal circuits, exerting differential regulatory effects on the function and fate of gastric immune cells. Future studies are warranted to elucidate further how varying EA frequencies affect the autonomic regulation of gastric innervation and the associated neuro-immune crosstalk.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the work was primarily performed in a rat model, and thus, the direct applicability of these findings to clinical practice requires further validation in human studies. Second, although immunofluorescence co-localization provided evidence suggesting that M2 macrophages undergo pyroptosis, the underlying molecular mechanisms could be elucidated more precisely in future studies using cell-specific cGAS/STING knockdown models or pharmacological inhibitors. Third, the current investigation was limited to an 8-week observation period. Therefore, the long-term protective effects of extended EA interventions on DGP, as well as their sustained influence on the cGAS-STING signaling pathway, remain to be determined.

In conclusion, this study elucidated the mechanism by which EA alleviates DGP. By suppressing the aberrant activation of the cGAS-STING signaling pathway in gastric tissues and mitigating pyroptotic death of M2 macrophages, EA preserves the integrity of the ICC network and restores gastric motility. These findings not only establish a solid molecular and immunological basis for the therapeutic role of EA in DGP but also highlight the cGAS-STING/pyroptosis axis as a pivotal contributor to DGP pathogenesis and a promising therapeutic target. This work further provides a novel perspective for refining EA stimulation parameters and for advancing the development of targeted pharmacological interventions.

| 1. | Bharucha AE, Kudva YC, Prichard DO. Diabetic Gastroparesis. Endocr Rev. 2019;40:1318-1352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 22.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 2. | Koch KL, Calles-Escandón J. Diabetic gastroparesis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2015;44:39-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Shen S, Xu J, Lamm V, Vachaparambil CT, Chen H, Cai Q. Diabetic Gastroparesis and Nondiabetic Gastroparesis. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2019;29:15-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ahmed MSO, Forde H, Smith D. Diabetic gastroparesis: clinical features, diagnosis and management. Ir J Med Sci. 2023;192:1687-1694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Camilleri M, Chedid V, Ford AC, Haruma K, Horowitz M, Jones KL, Low PA, Park SY, Parkman HP, Stanghellini V. Gastroparesis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 287] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 32.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yin J, Chen J, Chen JD. Ameliorating effects and mechanisms of electroacupuncture on gastric dysrhythmia, delayed emptying, and impaired accommodation in diabetic rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;298:G563-G570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Liu JH, Yan J, Yi SX, Chang XR, Lin YP, Hu JM. Effects of electroacupuncture on gastric myoelectric activity and substance P in the dorsal vagal complex of rats. Neurosci Lett. 2004;356:99-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zila I, Mokra D, Kopincova J, Kolomaznik M, Javorka M, Calkovska A. Vagal-immune interactions involved in cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. Physiol Res. 2017;66:S139-S145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wang H, Zhao K, Ba Y, Gao T, Shi N, Niu Q, Liu C, Chen Y. Gastric Electrical Pacing Reduces Apoptosis of Interstitial Cells of Cajal via Antioxidative Stress Effect Attributing to Phenotypic Polarization of M2 Macrophages in Diabetic Rats. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021;2021:1298657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chen Y, Xu JJ, Liu S, Hou XH. Electroacupuncture at ST36 ameliorates gastric emptying and rescues networks of interstitial cells of Cajal in the stomach of diabetic rats. PLoS One. 2013;8:e83904. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Singh R, Ha SE, Wei L, Jin B, Zogg H, Poudrier SM, Jorgensen BG, Park C, Ronkon CF, Bartlett A, Cho S, Morales A, Chung YH, Lee MY, Park JK, Gottfried-Blackmore A, Nguyen L, Sanders KM, Ro S. miR-10b-5p Rescues Diabetes and Gastrointestinal Dysmotility. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:1662-1678.e18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ordög T, Takayama I, Cheung WK, Ward SM, Sanders KM. Remodeling of networks of interstitial cells of Cajal in a murine model of diabetic gastroparesis. Diabetes. 2000;49:1731-1739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Grover M, Farrugia G, Stanghellini V. Gastroparesis: a turning point in understanding and treatment. Gut. 2019;68:2238-2250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 24.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Vinik AI, Maser RE, Mitchell BD, Freeman R. Diabetic autonomic neuropathy. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1553-1579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1258] [Cited by in RCA: 1245] [Article Influence: 54.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bain CC, Mowat AM. Macrophages in intestinal homeostasis and inflammation. Immunol Rev. 2014;260:102-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 357] [Cited by in RCA: 482] [Article Influence: 43.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (14)] |

| 16. | De Schepper S, Verheijden S, Aguilera-Lizarraga J, Viola MF, Boesmans W, Stakenborg N, Voytyuk I, Schmidt I, Boeckx B, Dierckx de Casterlé I, Baekelandt V, Gonzalez Dominguez E, Mack M, Depoortere I, De Strooper B, Sprangers B, Himmelreich U, Soenen S, Guilliams M, Vanden Berghe P, Jones E, Lambrechts D, Boeckxstaens G. Self-Maintaining Gut Macrophages Are Essential for Intestinal Homeostasis. Cell. 2018;175:400-415.e13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 423] [Article Influence: 52.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yao H, Tang G. Macrophages in intestinal fibrosis and regression. Cell Immunol. 2022;381:104614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chen X, Meng X, Zhang H, Feng C, Wang B, Li N, Abdullahi KM, Wu X, Yang J, Li Z, Jiao C, Wei J, Xiong X, Fu K, Yu L, Besner GE, Feng J. Intestinal proinflammatory macrophages induce a phenotypic switch in interstitial cells of Cajal. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:6443-6456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cipriani G, Gibbons SJ, Verhulst PJ, Choi KM, Eisenman ST, Hein SS, Ordog T, Linden DR, Szurszewski JH, Farrugia G. Diabetic Csf1(op/op) mice lacking macrophages are protected against the development of delayed gastric emptying. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;2:40-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wang LX, Zhang SX, Wu HJ, Rong XL, Guo J. M2b macrophage polarization and its roles in diseases. J Leukoc Biol. 2019;106:345-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 680] [Article Influence: 85.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Orecchioni M, Ghosheh Y, Pramod AB, Ley K. Macrophage Polarization: Different Gene Signatures in M1(LPS+) vs. Classically and M2(LPS-) vs. Alternatively Activated Macrophages. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 765] [Cited by in RCA: 1522] [Article Influence: 217.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Boraschi D, Dinarello CA. IL-18 in autoimmunity: review. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2006;17:224-252. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Brown GC. Cell death by phagocytosis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2024;24:91-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 38.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ip WKE, Hoshi N, Shouval DS, Snapper S, Medzhitov R. Anti-inflammatory effect of IL-10 mediated by metabolic reprogramming of macrophages. Science. 2017;356:513-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 625] [Cited by in RCA: 1073] [Article Influence: 134.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kim TH, Yang K, Kim M, Kim HS, Kang JL. Apoptosis inhibitor of macrophage (AIM) contributes to IL-10-induced anti-inflammatory response through inhibition of inflammasome activation. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12:19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Rao Z, Zhu Y, Yang P, Chen Z, Xia Y, Qiao C, Liu W, Deng H, Li J, Ning P, Wang Z. Pyroptosis in inflammatory diseases and cancer. Theranostics. 2022;12:4310-4329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 548] [Article Influence: 137.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Vasudevan SO, Behl B, Rathinam VA. Pyroptosis-induced inflammation and tissue damage. Semin Immunol. 2023;69:101781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 81.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Exconde PM, Hernandez-Chavez C, Bourne CM, Richards RM, Bray MB, Lopez JL, Srivastava T, Egan MS, Zhang J, Yoo W, Shin S, Discher BM, Taabazuing CY. The tetrapeptide sequence of IL-18 and IL-1β regulates their recruitment and activation by inflammatory caspases. Cell Rep. 2023;42:113581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Gulen MF, Samson N, Keller A, Schwabenland M, Liu C, Glück S, Thacker VV, Favre L, Mangeat B, Kroese LJ, Krimpenfort P, Prinz M, Ablasser A. cGAS-STING drives ageing-related inflammation and neurodegeneration. Nature. 2023;620:374-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 545] [Cited by in RCA: 593] [Article Influence: 197.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Hopfner KP, Hornung V. Molecular mechanisms and cellular functions of cGAS-STING signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020;21:501-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 341] [Cited by in RCA: 1455] [Article Influence: 242.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Zhang X, Bai XC, Chen ZJ. Structures and Mechanisms in the cGAS-STING Innate Immunity Pathway. Immunity. 2020;53:43-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 244] [Cited by in RCA: 594] [Article Influence: 99.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Chen Q, Sun L, Chen ZJ. Regulation and function of the cGAS-STING pathway of cytosolic DNA sensing. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:1142-1149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 928] [Cited by in RCA: 1742] [Article Influence: 193.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Paul BD, Snyder SH, Bohr VA. Signaling by cGAS-STING in Neurodegeneration, Neuroinflammation, and Aging. Trends Neurosci. 2021;44:83-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 46.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | He S, Pan T, Tian R, He Q, Cheng D, Qu H, Li R, Tan R. Fatty acid synthesis promotes mtDNA release via ETS1-mediated oligomerization of VDAC1 facilitating endothelial dysfunction in sepsis-induced lung injury. Cell Death Differ. 2025;32:2177-2192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Shi J, Zhao Y, Wang K, Shi X, Wang Y, Huang H, Zhuang Y, Cai T, Wang F, Shao F. Cleavage of GSDMD by inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature. 2015;526:660-665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2573] [Cited by in RCA: 5037] [Article Influence: 457.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Li S, Sun Y, Song M, Song Y, Fang Y, Zhang Q, Li X, Song N, Ding J, Lu M, Hu G. NLRP3/caspase-1/GSDMD-mediated pyroptosis exerts a crucial role in astrocyte pathological injury in mouse model of depression. JCI Insight. 2021;6:e146852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 48.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Wei X, Lin Y, Zhao D, Xiao X, Chen Q, Chen S, Peng Y. Electroacupuncture Relieves Suppression of Autophagy in Interstitial Cells of Cajal of Diabetic Gastroparesis Rats. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;2020:7920715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Zhang S, Zhang C, Fan M, Chen T, Yan H, Shi N, Chen Y. Neuromodulation and Functional Gastrointestinal Disease. Neuromodulation. 2024;27:243-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/