Published online Feb 15, 2026. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v17.i2.113221

Revised: October 24, 2025

Accepted: December 12, 2025

Published online: February 15, 2026

Processing time: 171 Days and 14.9 Hours

Diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a cardiac muscle disorder that causes heart failure independently of coronary artery disease. This condition remains a major clinical challenge, as current therapies primarily address traditional risk factors rather than the underlying molecular pathology. In this regard, endothelial dys

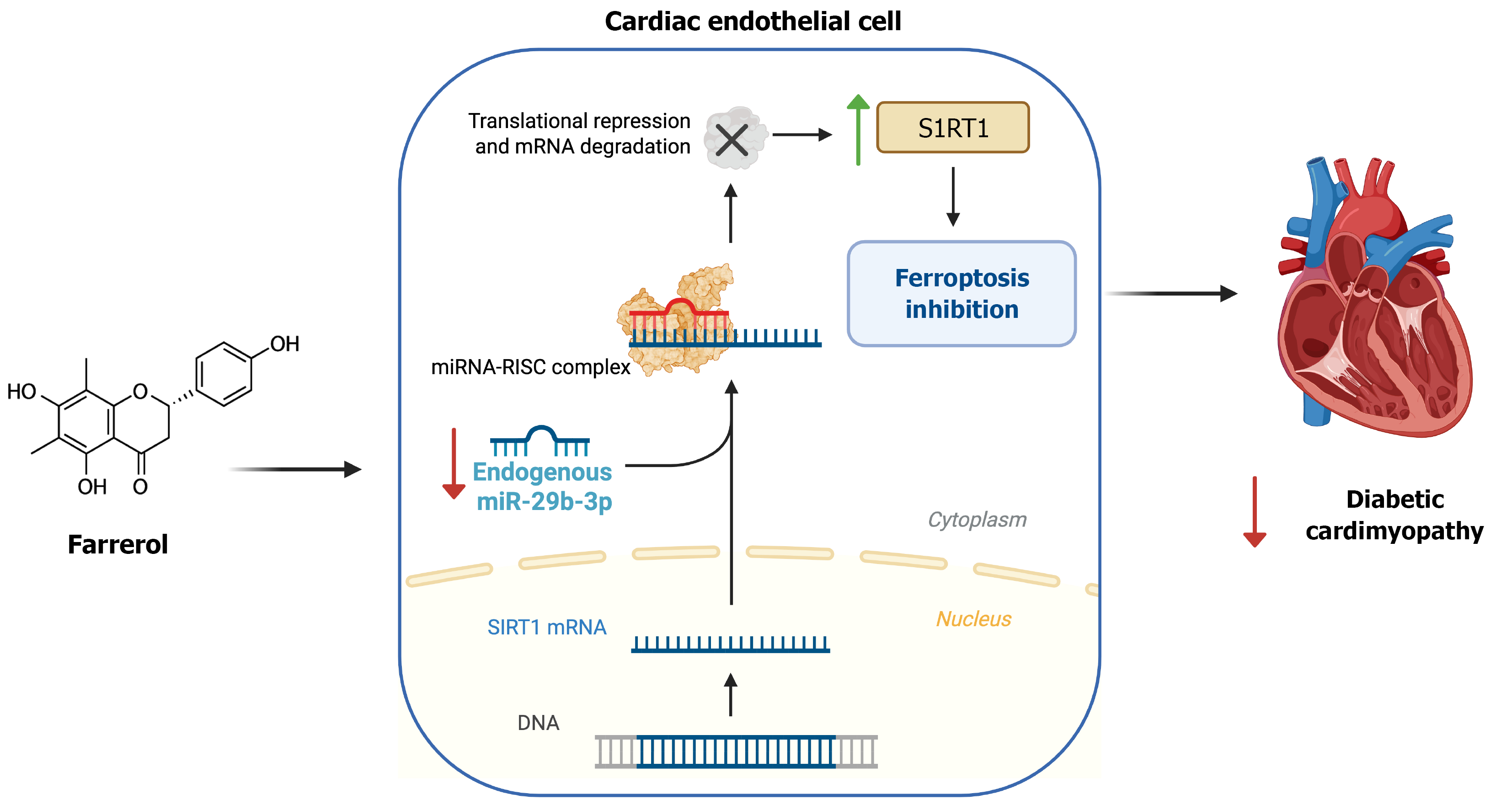

Core Tip: Diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a diabetes-related form of heart failure that lacks targeted therapies. Recent evidence identifies endothelial ferroptosis, an iron-dependent form of cell death, as a central driver of cardiac microvascular injury in DCM. Guo et al demonstrate that Farrerol, a natural flavonoid, inhibits ferroptosis by downregulating microRNA-29b-3p and restoring sirtuin 1 signaling in endothelial cells, thereby improving cardiac function and reducing fibrosis in diabetic mice. Targeting endothelial ferroptosis through the microRNA-29b-3p/sirtuin 1 pathway represents a novel disease-modifying strategy for DCM.

- Citation: Donate-Correa J, Martínez-Alberto CE. Farrerol and the miR-29b-3p/sirtuin 1 pathway: A mechanistic breakthrough in protecting the diabetic heart. World J Diabetes 2026; 17(2): 113221

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v17/i2/113221.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v17.i2.113221

Diabetes mellitus affects approximately 9% of the world's population, and its prevalence is projected to exceed 10% by 2045[1]. Among diabetes-related complications, diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) has emerged as a leading cause of heart failure in this population[2]. This condition is a type of heart failure that develops independently of hypertension or coronary artery disease, characterized by the development of diastolic dysfunction, myocardial fibrosis, and eventually systolic deterioration. There is increasing evidence indicating that cardiac microvascular dysfunction plays a central role in the pathogenesis of dilated cardiomyopathy; thus, chronic hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia are thought to induce progressive injury to cardiac microvascular endothelial cells, leading to reduced capillary perfusion, myocardial ischemia, and interstitial fibrosis[3]. Indeed, the loss of normal endothelial function, including decreased nitric oxide bioavailability and increased oxidative stress, is a key trigger linking metabolic disorders to cardiac remodeling in diabetes[3,4]. Despite advances in glycemic control and standard therapies for heart failure, a considerable residual risk of cardiac deterioration remains in patients with diabetes, underscoring the need for novel interventions targeting these mechanisms.

One emerging culprit in diabetes-related tissue damage is ferroptosis, a distinct form of regulated cell death driven by iron-catalyzed lipid peroxidation. Unlike apoptosis or necroptosis, ferroptosis is uniquely iron-dependent and marked by the accumulation of toxic lipid peroxides in cell membranes[5]. This non-apoptotic cell death mechanism has been implicated in acute cardiovascular injuries such as myocardial infarction and ischemia-reperfusion injury, as well as in heart failure models[6,7]. In the context of diabetes, recent studies suggest that ferroptosis may also contribute to cardiometabolic disorders and complications[7,8]. Therefore, the excess of reactive oxygen species and iron overload in diabetes can create a permissive environment for ferroptotic cell death, compounding organ damage. However, the involvement of ferroptosis in chronic diabetic heart disease had not been fully elucidated until now.

Importantly, endothelial cells appear especially vulnerable to ferroptosis in diabetic conditions. Endothelial ferroptosis has been linked to atherosclerotic plaque instability in diabetes and to impaired angiogenic wound healing in diabetic ulcers[8,9]. These observations raised the question of whether ferroptosis might also drive the microvascular endothelial injury underlying DCM. Guo et al[10] have addressed this question in a recent study by investigating the role of endothelial ferroptosis in a mouse model of DCM and testing a novel therapeutic strategy to counter it. Their work identifies a microRNA (miR)-mediated ferroptotic pathway in diabetic cardiac endothelial cells and demonstrate that its modulation can ameliorate cardiomyopathy. In particular, Guo et al[10] show that farrerol, a natural compound with known antioxidant properties, protects the diabetic heart by inhibiting endothelial ferroptosis via the miR-29b-3p/sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) signaling pathway. This editorial will discuss the mechanistic insights from that study, the therapeutic implications of targeting endothelial ferroptosis, and the future challenges in translating these findings into clinical practice.

A key novelty of the study by Guo et al[10] is the identification of endothelial ferroptosis as a triggering factor in DCM and the elucidation of the miR-29b-3p/SIRT1 pathway as its regulatory mechanism. MiRs are small non-coding RNAs that post-transcriptionally regulate gene expression, often optimizing cell survival and stress responses. Guo et al[10] focused on miR-29b-3p based on preliminary RNA sequencing data and bioinformatics predictions, and discovered a crucial link between this miR and ferroptosis in diabetic cardiac microvascular endothelial cells.

In diabetic mice, cardiac endothelial cells exhibited evidence of ferroptosis, including lipid peroxidation and ultrastructural mitochondrial changes, contributing to capillary rarefaction and myocardial damage. Farrerol treatment potently suppressed these ferroptotic changes in the endothelium, which was associated with preservation of microvascular density and improved cardiac function[10]. At the molecular level, farrerol was found to downregulate miR-29b-3p in cardiac endothelial cells. This is significant because miR-29b-3p directly targets SIRT1, a deacetylase enzyme that plays a well-established role in cellular stress resistance and metabolism. In the untreated diabetic hearts, elevated miR-29b-3p correlated with depressed SIRT1 protein levels, suggesting that diabetes-induced miR-29b-3p may silence a key endothelial survival factor. Guo et al[10] confirmed the direct interaction between miR-29b-3p and the 3′UTR of SIRT1 mRNA through a luciferase reporter assay, firmly establishing SIRT1 as a target of miR-29b-3p in these cells (Figure 1).

Restoring SIRT1 is likely pivotal for inhibiting ferroptosis. SIRT1 is known to enhance antioxidant defenses and mitochondrial function, for example by activating the nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathway and modulating glutathione metabolism, thereby countering the lipid peroxidation that drives ferroptosis[11]. In line with this, the study found that the downregulation of miR-29b-3p elicited by farrerol led to upregulation of SIRT1 in endothelial cells, which would be expected to increase the resistance to ferroptotic cell death. The causal role of the miR-29b-3p/SIRT1 axis was demonstrated by administrating a miR-29b-3p inhibitor (antagomir) in diabetic mice which mimicked the protective effects of farrerol on the cardiac microvasculature and function, whereas overexpression of miR-29b-3p abolished the benefits of farrerol[10]. Thus, endothelial ferroptosis in DCM is regulated by a miR-gene circuit, where miR-29b-3p promotes ferroptotic injury by repressing the SIRT1-mediated anti-oxidative program. Farrerol, by tipping the balance of this circuit (lowering miR-29b-3p and increasing SIRT1), emerges as a ferroptosis suppressor.

It is worth noting that miR-29b-3p has been implicated in vascular cell injury in other diabetic complications as well. For example, in models of diabetic retinopathy, miR-29b-3p upregulation was shown to trigger retinal microvascular endothelial cell apoptosis by suppressing SIRT1[12]. The results of Guo et al[10] extend this concept to ferroptosis and the heart, highlighting the concept that diabetes-induced miRs can inactivate endothelial protective pathways (such as SIRT1), leading to cell death and organ damage. By rescuing SIRT1, farrerol may restore the endothelial defenses. This mechanistic insight into endothelial ferroptosis adds a new dimension to our understanding of DCM. It shifts some focus from cardiomyocytes to the often-overlooked microvascular endothelial cells, and identifies a the miR-29b-3p/SIRT1 axis as a novel molecular target that can be modulated to protect the diabetic heart.

The findings by Guo et al[10] have potential therapeutic implications, pointing toward endothelial protection and ferroptosis inhibition as a strategy to combat DCM. Farrerol, in particular, emerges as a promising lead compound. Farrerol is a bioactive flavanone isolated from the medicinal plant Rhododendron dauricum, traditionally used in Chinese medicine (“Man-shan-hong”) for its antitussive and anti-inflammatory effects[13]. As a natural product, farrerol is notable for its broad pharmacological profile and low toxicity in preclinical studies. Prior research has demonstrated several beneficial activities of farrerol that complement its newly discovered anti-ferroptotic role. For instance, farrerol can attenuate inflammatory responses by modulating Toll-like receptor 4 signaling in microglial cells[14], and it sup

With respect to cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, farrerol has already shown therapeutic potential. A recent experimental study in type 2 diabetic rats demonstrated that farrerol alleviates DCM by activating AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and improving cardiac lipid metabolism[16]. That study indicated that farrerol can reduce myocardial triglyceride accumulation and ameliorate cardiac dysfunction in diabetes, albeit via a mechanism distinct from ferroptosis. The work by Guo et al[10] complements and extends these findings by showing that farrerol also preserves the cardiac microvasculature and prevents cell death. The dual action on the cardiomyocyte and microvascular aspects of the disease, by improving myocardial energy metabolism and preventing endothelial ferroptotic injury, makes farrerol especially attractive as a multifaceted therapy for dilated cardiomyopathy. Moreover, the antiferroptotic ability of farrerol has been previously observed; thus it was reported to protect against collagenase-induced tendinopathy by blocking ferroptosis in tendon cells[15], and to reduce hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in neonatal rats via activating Nrf2 (an upstream regulator of anti-ferroptotic defenses)[17]. These convergent findings underscore that farrerol is a potent inhibitor of pathological cell death across different tissues, likely through its enhancement of anti-oxidant pathways.

From a translational perspective, using a natural compound like farrerol to target a novel pathway in DCM is com

Another implication is the potential to target miR-29b-3p itself as a therapy. While farrerol indirectly modulates this miR, one could envision developing oligonucleotide therapeutics (such as antagomirs) to specifically inhibit miR-29b-3p in cardiac endothelium. Indeed, miRs are being explored as drug targets in cardiovascular disease[18]. However, delivering such molecules to the heart in a cell-specific manner remains challenging. Conversely, farrerol is a small molecule that can be orally administered and reach the heart, as demonstrated in the animal studies. It effectively acts as a chemical miR-29b suppressor and SIRT1 activator. Natural polyphenols and flavonoids (e.g., resveratrol, quercetin) have a precedent of modulating SIRT1 and related pathways, but farrerol appears unique in its ability to impact the miR/SIRT1/ferroptosis axis. Altogether, the therapeutic implication is that farrerol or its derivatives could be developed as a novel class of therapy for DCM, one that targets the root cause of microvascular injury and thereby interrupts the vicious cycle of ischemia, oxidative stress, and myocardial fibrosis in the diabetic heart. Given the growing success of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in reducing diabetic heart failure, it is conceivable that farrerol’s endothelial and anti-ferroptotic actions could complement these agents. Exploring such combinatorial strategies might yield additive or synergistic protection by concurrently addressing metabolic stress, oxidative injury, and microvascular dysfunction.

While the protective effects of Farrerol in DCM are promising, several challenges must be addressed before these insights can translate into clinical therapy. First, the evidence so far is from preclinical models (mice with streptozotocin-induced diabetes and high-fat diet). It will be important to validate the role of endothelial ferroptosis in human DCM. For example, analyzing myocardial biopsies or autopsy samples from diabetic patients for markers of ferroptosis (such as 4-hydroxynonenal or glutathione peroxidase 4 expression) could confirm whether this cell death process is indeed active in human DCM. Similarly, assessing circulating or cardiac tissue levels of miR-29b-3p in patients could indicate whether the miR-29b-3p/SIRT1 pathway is dysregulated in clinical disease. If human data corroborate the animal findings, it would strengthen the rationale for moving farrerol toward clinical trials.

Another challenge lies in drug delivery and pharmacokinetics. Like many flavonoids, farrerol displays rapid hepatic metabolism, low aqueous solubility, and limited tissue penetration, which may reduce its bioavailability in the heart. Several strategies could enhance its translational feasibility: (1) Nanoparticle encapsulation (e.g., lipid or polymeric nanocarriers) to prolong systemic circulation and facilitate endothelial uptake; (2) PEGylation or liposomal formulations to improve solubility and protect against first-pass metabolism; and (3) Pro-drug or structural analog design to optimize cardiac distribution. Combining these approaches with endothelial-specific targeting ligands may maximize microvas

The pleiotropic nature of farrerol, while generally beneficial, also warrants careful evaluation of off-target effects. By influencing pathways like AMPK, Toll-like receptor 4, Nrf2, and others, farrerol could theoretically have unintended consequences in certain contexts. For example, systemic SIRT1 activation might affect metabolic processes in the liver or adipose tissue. Although such effects might be positive (e.g., improving insulin sensitivity), they should be thoroughly studied. Long-term safety data will be needed, especially since natural compounds can sometimes have subtle toxicities or interact with other medications. Available preclinical evidence indicates a favorable safety profile. In rodent studies, repeated oral administration of farrerol at doses up to 200 mg/kg/day for four weeks produced no hepatic, renal, or hematologic toxicity, while improving metabolic indices. Nonetheless, systematic toxicokinetic and chronic exposure studies remain mandatory before initiating first-in-human evaluation. Encouragingly, the historical use of Rhododendron dauricum in traditional medicine implies a favorable safety margin, but rigorous toxicological studies in multiple animal species and eventually humans are required.

An additional consideration is the specificity of targeting miR-29b-3p. MiR-29 family members (which include miR-29a, b, and c) have diverse roles in different tissues. Notably, miR-29 is known to regulate extracellular matrix production, limiting the development of fibrosis by suppressing collagen synthesis in fibroblasts. There is some concern that broad inhibition of miR-29 might remove a brake on fibrosis in certain organs. However, and in the context of DCM, Guo et al[10] observed that inhibiting miR-29b-3p actually reduced cardiac fibrosis, likely because the dominant effect was via improving microvascular perfusion and reducing endothelial-to-mesenchymal activation. This highlights the complexity of miR therapeutics, where the outcome can depend on which cell type is targeted. Going forward, strategies to target miR-29b-3p or SIRT1 specifically in endothelial cells (for example, using endothelial-specific promoters in gene therapy, or targeted lipid nanoparticles delivering antisense oligonucleotides) would be valuable to avoid unwanted effects in other cell types. Notably, miR-29a, b, and c share partial seed sequence overlap yet differ in tissue distribution and target selectivity. Off-target inhibition of miR-29a/c could disrupt antifibrotic programs in non-cardiac organs such as liver or kidney. To mitigate this, future research should employ isoform-specific antagomirs and cell-restricted delivery systems, for example, endothelial-targeted nanoparticles, to ensure selective modulation of miR-29b-3p within the cardiac microvasculature.

From a drug development and regulatory standpoint, translating a natural compound like farrerol into a clinically approved medication will require navigating the same rigorous pathway as any new drug. Key steps include standardizing the compound (ensuring purity and consistent bioavailability), scaling up production, and performing well-controlled trials. Regulatory agencies will require clear demonstrations of efficacy in animal models (which this study provides a strong basis for) and safety in toxicity studies. Given that farrerol is not yet widely studied in humans, early-phase clinical trials would likely start by assessing its pharmacokinetics, tolerability, and optimal dosing in healthy volunteers, followed by proof-of-concept studies in patients with diabetes. It is worth noting that some natural compounds have reached clinical trial stages for diabetic complications (for instance, berberine and others in Chinese herbal medicine have been tested for diabetic nephropathy), so there is precedent. However, farrerol will need to compete with other emerging therapies. Any move into clinical application would benefit from demonstrating that farrerol can add value on top of existing standard-of-care (such as renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockers, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, or glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists that have cardiovascular benefits in diabetes). Perhaps farrerol could be eventually used in combination with these agents, providing microvascular protection in parallel with the hemodynamic and metabolic improvements offered by current drugs.

Although the current evidence relies on murine models combining streptozotocin and a high-fat diet, validating these mechanisms in human DCM is essential. Future work should evaluate endothelial ferroptosis markers such as 4-hydroxynonenal accumulation, glutathione peroxidase 4 depletion, and miR-29b-3p/SIRT1 dysregulation in myocardial biopsies or autopsy samples from diabetic patients. In vitro, human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived endothelial cells represent a valuable translational platform to test farrerol’s endothelial and anti-ferroptotic effects in a human context. Integrating such humanized models would bridge the current preclinical-clinical gap and validate farrerol’s therapeutic potential.

It should also be noted that species-specific compensatory mechanisms may attenuate disease severity in mice. Unlike humans, murine models often maintain cardiac output despite microvascular injury and lack the chronic comorbidities, such as hypertension, renal impairment, and dyslipidemia, that accelerate DCM progression in patients. Consequently, future studies combining diabetic and hypertensive models or using aged animals could provide a more faithful representation of human disease complexity.

Although the present findings provide a compelling mechanistic framework, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the streptozotocin-induced diabetic model primarily reflects type 1 diabetes and carries inherent β-cell toxicity, limiting extrapolation to the more prevalent type 2 diabetes context. Validation in genetic (db/db, ob/ob) and diet-induced models will be essential to confirm mechanistic generality. Second, the pleiotropic nature of farrerol, acting on AMPK, lipid metabolism, and inflammatory signaling, complicates attribution of its cardioprotective effects solely to the miR-29b-3p/SIRT1/ferroptosis pathway. Targeted inhibition experiments (e.g., with SIRT1 or AMPK blockers) are required to delineate causality. Third, the context-dependent roles of miR-29 family members pose potential safety concerns: Systemic suppression may inadvertently promote fibrosis in other organs. Endothelial-targeted delivery approaches are therefore indispensable for therapeutic development. Lastly, the absence of human validation data underscores the need for translational studies using patient-derived endothelial cells or myocardial tissues.

The study by Guo et al[10] represents an important milestone in our understanding of DCM and its potential treatment. It shines a spotlight on cardiac microvascular endothelial ferroptosis as a previously under-recognized mechanism driving diabetic heart disease, and importantly, it offers a solution to counteract this mechanism through the natural compound Farrerol. These findings deepen the paradigm that diabetic complications can be alleviated by targeting fundamental cell death and stress pathways. By inhibiting ferroptosis via the miR-29b-3p/SIRT1 axis, farrerol preserved the microvasculature and function of heart in diabetic mice, essentially demonstrating that DCM is modifiable when the right molecular lever is pulled. This not only provides hope that to slow the progression of DCM, but also establishes a new therapeutic avenue centered on endothelial health.

Looking ahead, further exploration of endothelial-targeted therapies could pave the way for disease-modifying treatments for DCM. The concept of “ferroptosis inhibition” may join the armamentarium alongside metabolic control and neurohormonal blockade in combating diabetic heart failure. Nonetheless, translating these promising results into the clinical scenario will require multidisciplinary efforts that will include: Validating biomarkers of ferroptosis in patients, designing targeted delivery systems, and conducting carefully phased clinical trials. If successful, such efforts could substantially reduce the burden of diabetes-related cardiac failure. In summary, targeting endothelial ferroptosis emerges as an exciting strategy to change the trajectory of DCM, improving both the quality and longevity of life for millions of patients worldwide.

| 1. | Saeedi P, Petersohn I, Salpea P, Malanda B, Karuranga S, Unwin N, Colagiuri S, Guariguata L, Motala AA, Ogurtsova K, Shaw JE, Bright D, Williams R; IDF Diabetes Atlas Committee. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9(th) edition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;157:107843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5345] [Cited by in RCA: 6427] [Article Influence: 918.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (12)] |

| 2. | Zhong L, Hou X, Tian Y, Fu X. Exercise and dietary interventions in the management of diabetic cardiomyopathy: mechanisms and implications. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2025;24:159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zhan J, Chen C, Wang DW, Li H. Hyperglycemic memory in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Front Med. 2022;16:25-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wilson AJ, Gill EK, Abudalo RA, Edgar KS, Watson CJ, Grieve DJ. Reactive oxygen species signalling in the diabetic heart: emerging prospect for therapeutic targeting. Heart. 2018;104:293-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS, Morrison B 3rd, Stockwell BR. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell. 2012;149:1060-1072. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4711] [Cited by in RCA: 13422] [Article Influence: 958.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 6. | Fang X, Ardehali H, Min J, Wang F. The molecular and metabolic landscape of iron and ferroptosis in cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2023;20:7-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 738] [Article Influence: 246.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wang Z, Wu C, Yin D, Dou K. Ferroptosis: mechanism and role in diabetes-related cardiovascular diseases. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2025;24:60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wang S, Song X, Gao H, Zhang Y, Zhou X, Wang F. 6-Gingerol Inhibits Ferroptosis in Endothelial Cells in Atherosclerosis by Activating the NRF2/HO-1 Pathway. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2025;197:3890-3906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yin Y, Guo W, Chen Q, Tang Z, Liu Z, Lin R, Pan T, Zhan J, Ren L. A Single H(2)S-Releasing Nanozyme for Comprehensive Diabetic Wound Healing through Multistep Intervention. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2025;17:18134-18149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Guo Y, Yu XR, Gu HD, Wang YJ, Yang ZG, Chi JF, Zhang LP, Lin H. Farrerol ameliorates diabetic cardiomyopathy by inhibiting ferroptosis via miR-29b-3p/SIRT1 signaling pathway in endothelial cells. World J Diabetes. 2025;16:109553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zhang Y, Kong F, Li N, Tao L, Zhai J, Ma J, Zhang S. Potential role of SIRT1 in cell ferroptosis. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2025;13:1525294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zeng Y, Cui Z, Liu J, Chen J, Tang S. MicroRNA-29b-3p Promotes Human Retinal Microvascular Endothelial Cell Apoptosis via Blocking SIRT1 in Diabetic Retinopathy. Front Physiol. 2019;10:1621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zhang J, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Lu K, Zhang X, Wang X, Fu J. Farrerol alleviates cognitive impairments in chronic cerebral hypoperfusion via suppressing NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2025;153:114442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cui B, Guo X, You Y, Fu R. Farrerol attenuates MPP(+) -induced inflammatory response by TLR4 signaling in a microglia cell line. Phytother Res. 2019;33:1134-1141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wu Y, Qian J, Li K, Li W, Yin W, Jiang H. Farrerol alleviates collagenase-induced tendinopathy by inhibiting ferroptosis in rats. J Cell Mol Med. 2022;26:3483-3494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tu J, Liu Q, Sun H, Gan L. Farrerol Alleviates Diabetic Cardiomyopathy by Regulating AMPK-Mediated Cardiac Lipid Metabolic Pathways in Type 2 Diabetic Rats. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2024;82:2427-2437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Li Y, Wang T, Sun P, Zhu W, Chen Y, Chen M, Yang X, Du X, Zhao Y. Farrerol Alleviates Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy by Inhibiting Ferroptosis in Neonatal Rats via the Nrf2 Pathway. Physiol Res. 2023;72:511-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Laggerbauer B, Engelhardt S. MicroRNAs as therapeutic targets in cardiovascular disease. J Clin Invest. 2022;132:e159179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 25.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/