Published online Feb 15, 2026. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v17.i2.113149

Revised: September 14, 2025

Accepted: December 25, 2025

Published online: February 15, 2026

Processing time: 174 Days and 15.4 Hours

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), the updated terminology for fatty liver disease linked to metabolic dysfunction, is highly prevalent among individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). MASLD affects a majority of patients with T2DM and markedly increases the risk of fibrosis, cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and cardiovascular mortality. The pathogenesis in diabetic populations reflects a convergence of insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, mitochondrial dysfunction, chronic inflammation, and genetic predisposition. Advances in non-invasive diagnostics, including elastography and serum biomarkers, enable earlier identification and staging of disease, though limitations remain in diabetic cohorts. Lifestyle modification is the cornerstone of therapy, yet emerging pharmacotherapies are reshaping the therapeutic landscape. Antidiabetic agents such as glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors, and pioglitazone show hepatic benefits beyond glycemic control, while novel agents and combination regimens are under active evaluation. This narrative review synthesizes current evidence on epidemiology, mechanisms, diagnostics, and therapeutics of MASLD in T2DM, and highlights future directions in precision medicine. Integration of multidisciplinary care is essential to address this converging epidemic.

Core Tip: Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease is highly prevalent among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, amplifying risks of fibrosis, cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and cardiovascular disease. The pathogenesis reflects overlapping mechanisms of insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, inflammation, and genetic predisposition. This narrative review integrates updated evidence on epidemiology, diagnostics, and therapeutics, emphasizing the roles of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors, and emerging agents. A multidisciplinary, personalized approach remains essential to reduce the burden of this increasingly recognized disease spectrum.

- Citation: Suresh MG, Mohamed S, Geetha HS, Prabhu S, Trivedi N, Ng ZC, Mehta PD, Brar AS, Sohal A, Goyal MK, Hatwal J, Batta A. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and type 2 diabetes: Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and emerging therapeutic strategies. World J Diabetes 2026; 17(2): 113149

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v17/i2/113149.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v17.i2.113149

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) has become a major global health challenge, paralleling rising rates of obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Previously classified as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), the condition was redefined as MASLD to emphasize its metabolic origins rather than the exclusion of alcohol use. This nomenclature shift reflects the central role of insulin resistance, obesity, and car

T2DM and MASLD have a bidirectional, mutually reinforcing relationship. T2DM accelerates MASLD progression through worsening hepatic steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis, whereas MASLD contributes to worsening insulin resistance, heightened systemic inflammation, and increased cardiovascular risk among individuals with diabetes[5-7].

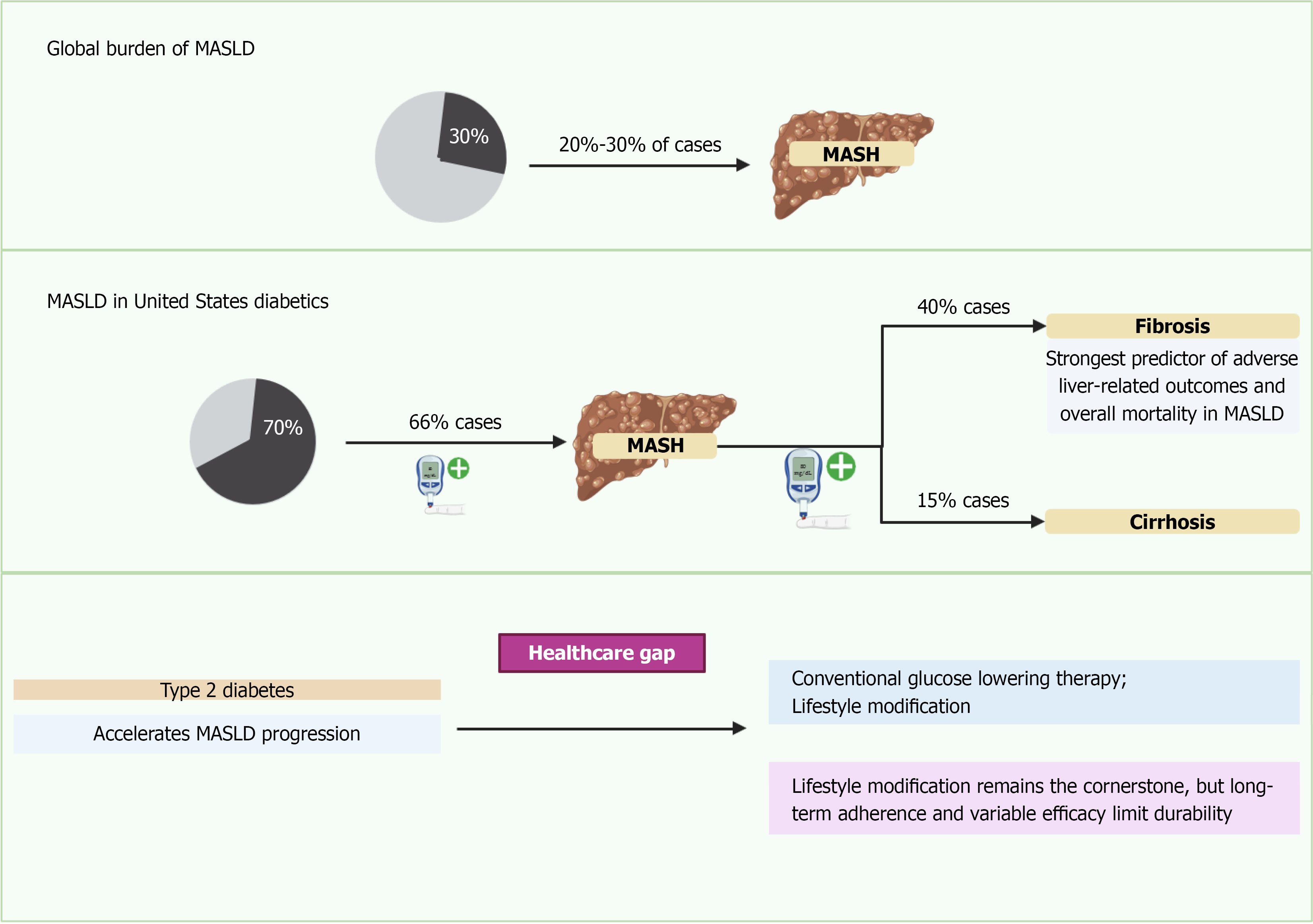

Epidemiologic data derived from studies using historical NAFLD/NASH criteria conceptually aligned with MASLD/MASH demonstrate that more than 70% of individuals with T2DM exhibit hepatic steatosis, and up to 30% develop steatohepatitis characterized by hepatocellular ballooning, lobular inflammation, and varying degrees of fibrosis. Among these features, fibrosis stage remains the strongest predictor of liver-related morbidity and mortality (Figure 1)[8,9].

The clinical implications of MASLD in T2DM extend well beyond hepatic outcomes. Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in this population, and MASLD consistently associates with elevated cardiovascular risk through shared metabolic mechanisms[7]. Additionally, data from historical NAFLD cohorts demonstrate associations with chronic kidney disease, sarcopenia, and several extrahepatic malignancies, compounding overall morbidity in individuals with diabetes[10-13].

Despite high prevalence, MASLD remains underrecognized and undertreated because the disease often progresses silently and historically lacked standardized screening pathways. Advances in non-invasive assessment including elastography and serum fibrosis scores have improved early detection and risk stratification, though diagnostic accuracy is reduced in individuals with T2DM[14,15].

No pharmacologic therapy is yet approved specifically for MASLD or MASH outside the United States. However, several glucose-lowering agents such as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT-2i), and pioglitazone demonstrate improvements in metabolic parameters and liver-related surrogate markers, though histologic benefit has been inconsistent across trials conducted under historical NAFLD/NASH definitions[4,16-18]. Numerous investigational therapies targeting lipid metabolism, bile acid signaling, and fibrogenesis are advancing through late-phase development.

This review summarizes current understanding of pathophysiology, diagnostic strategies, and established and emerging treatments, with specific attention to considerations unique to individuals with T2DM.

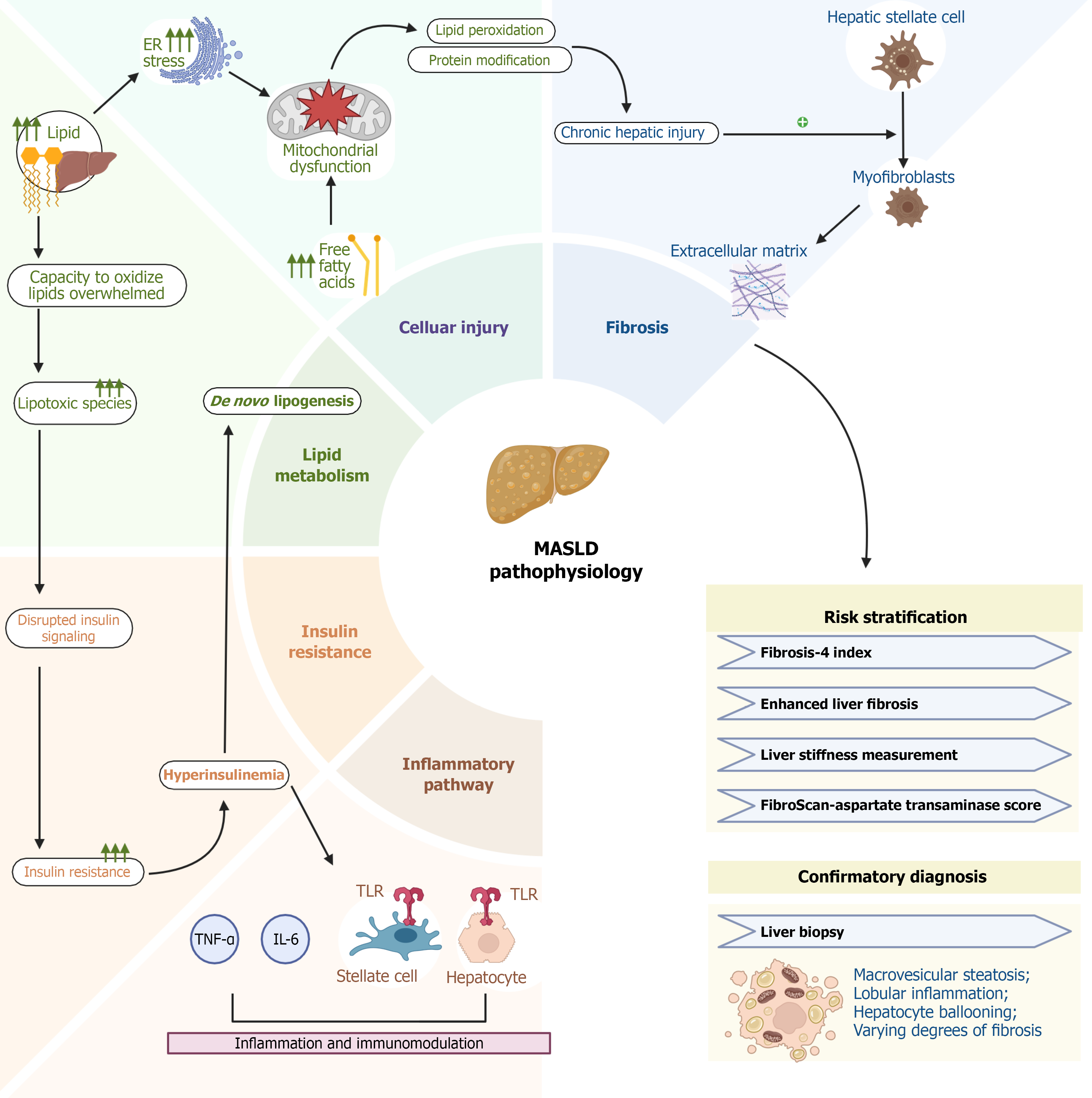

MASLD develops through interrelated disturbances in metabolic regulation, lipid handling, inflammation, and tissue remodeling. These mechanisms are amplified in individuals with T2DM, contributing to accelerated progression to MASH, advanced fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma[19].

Insulin resistance is a central driver of MASLD. Impaired hepatic insulin signaling reduces suppression of gluconeogenesis while maintaining lipogenic activity, resulting in increased de novo lipogenesis, reduced fatty acid oxidation, and triglyceride accumulation within hepatocytes[20]. Concurrent adipose tissue insulin resistance enhances lipolysis and increases free fatty acid delivery to the liver, promoting steatosis[21]. Steatosis alone does not fully explain disease progression, highlighting the importance of downstream lipotoxic and inflammatory mechanisms.

Lipotoxicity contributes to hepatocellular injury through the accumulation of diacylglycerols, ceramides, and saturated fatty acids, which impair mitochondrial function, induce endoplasmic reticulum stress, and promote oxidative injury[19,20,22-24]. These disturbances trigger activation of stress-related pathways including c-Jun N-terminal kinase, nuclear factor kappa-B, and the unfolded protein response leading to increased reactive oxygen species, lipid peroxidation, and DNA damage[22-26].

The resulting microenvironment stimulates Kupffer cells and hepatic stellate cells, initiating early inflammatory and fibrogenic cascades[22-26]. Hepatic macrophages and infiltrating immune cells amplify injury by releasing tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-6, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, contributing to hepatocyte ballooning and apoptosis histologic features associated with the transition from steatosis to MASH[27,28].

Fibrogenesis reflects an imbalance between extracellular matrix production and degradation. Cohort studies consistently show that fibrosis stage is the strongest predictor of liver-related and all-cause mortality in MASLD. Persistent metabolic injury, oxidative stress, and inflammation activate hepatic stellate cells, driving extracellular matrix deposition and progression from simple steatosis to advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis[29-33].

Disruption of the gut-liver axis contributes to MASLD pathogenesis. Dysbiosis and increased intestinal permeability permit microbial products such as lipopolysaccharide to reach the portal circulation, activating toll-like receptors on hepatic immune cells and amplifying inflammatory and fibrotic signaling[34-37]. Altered bile acid composition, reduced short-chain fatty acid production, and disturbances in choline metabolism further affect hepatic lipid regulation and immune activation, linking intestinal dysregulation to liver injury[38,39].

Genetic variants influence susceptibility and progression. Common polymorphisms in PNPLA3 (I148M), TM6SF2 (E167K), GCKR, and MBOAT7 are associated with increased hepatic steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis[40-43]. These variants also contribute to interindividual variability in disease severity and therapeutic responsiveness, supporting emerging precision-medicine strategies[44,45].

Epigenetic mechanisms including alterations in DNA methylation and microRNA expression further modify lipid metabolism and inflammatory pathways, adding complexity to MASLD pathogenesis[40-45].

MASLD arises from interconnected processes involving metabolic dysfunction, lipotoxic stress, immune activation, and fibrogenesis. These mechanisms are more pronounced in individuals with T2DM and vary substantially among patients, producing heterogeneous clinical trajectories. Continued refinement of mechanistic understanding as illustrated in Figure 2 will help inform risk stratification tools and guide development of targeted therapeutic interventions.

Diagnosing MASLD in individuals with T2DM is challenging because disease progression is often silent and liver enzyme levels may remain normal. Early recognition is essential, as patients with T2DM carry a disproportionately higher risk for advanced fibrosis and related complications[1].

Evaluation begins with identification of metabolic risk factors, routine laboratory testing, and the calculation of simple non-invasive fibrosis scores. The fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index is widely used due to its accessibility and cost-effectiveness; however, in T2DM it demonstrates a higher false-negative rate, particularly in individuals under 65 years of age and those with obesity, limiting sensitivity in this population[1,9,46,47]. Other serum-based scores such as the NAFLD fibrosis score and the aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index may be used as adjuncts, although their performance varies among diabetic cohorts.

Elastography-based techniques markedly improve risk stratification. Transient elastography (FibroScan®) and magnetic resonance elastography provide excellent negative predictive value for ruling out advanced fibrosis, making them valuable second-line tools following indeterminate or elevated FIB-4 scores. Quantitative imaging biomarkers, including controlled attenuation parameter and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-based proton density fat fraction (MRI-PDFF), enhance detection of steatosis but have limitations: MRI-PDFF quantifies hepatic fat yet does not reliably predict fibrosis progression, and remains unvalidated as a regulatory surrogate endpoint in MASLD trials[48-54].

Serologic markers such as the enhanced liver fibrosis score, cytokeratin-18 fragments, and emerging metabolomic or proteomic signatures offer additional non-invasive options. However, many require further validation in T2DM-enriched populations, where metabolic abnormalities may alter diagnostic thresholds or reduce accuracy[55-58].

Liver biopsy remains the reference standard for definitive staging, distinguishing steatosis from MASH, and determining clinical trial eligibility. Limitations include sampling variability, procedural risks, and cost, which restrict its routine use. In clinical practice, biopsy is generally reserved for patients with discordant non-invasive test results or when therapeutic decision-making requires histologic confirmation[59,60].

Major societies including the American Diabetes Association (ADA), American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), and European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) now recommend structured MASLD screening for all adults with T2DM. A commonly endorsed approach uses FIB-4 as the initial test, followed by elastography for individuals with indeterminate or elevated scores. Real-world implementation remains suboptimal. Embedding these tools into diabetes clinic workflows with electronic health record-based alerts, automated risk calculators, and streamlined referral pathways may significantly improve early detection and timely hepatology referral[15,47].

Management of MASLD requires a multifaceted approach that addresses metabolic dysfunction, hepatic inflammation, and fibrosis. Current strategies include lifestyle modification, optimization of metabolic comorbidities, and selective use of pharmacotherapies. Although no agent has been universally approved outside the United States solely for MASLD, several therapies used for T2DM or obesity offer hepatic benefits, and resmetirom has recently become the first Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drug for noncirrhotic MASH with fibrosis. Treatment selection should be individualized based on comorbidities, fibrosis stage, and patient-specific goals (Tables 1 and 2)[61-64].

| Drug | Class | Liver effects | CV/metabolic effects | Fibrosis impact | Ref. |

| Metformin | Biguanide | Unchanged | Improves insulin sensitivity | Neutral | Cusi et al[9] |

| Pioglitazone | PPAR-γ agonist | Decreased | Improves insulin sensitivity | Improved | Cusi et al[9] |

| Insulin | Hormone | Decreased | Glucose control | Unknown | Cusi et al[9] |

| GLP-1 RAs (semaglutide, liraglutide) | GLP-1 RA | Decreased | Weight loss, CV benefit | Improved | Cusi et al[9]; Lin et al[92] |

| SGLT2 inhibitors (dapagliflozin, empagliflozin, canagliflozin) | SGLT2 inhibitor | Decreased | Weight loss, glycemic control | Effect unknown | Cusi et al[9] |

| DPP-IV inhibitors (sitagliptin, vildagliptin) | DPP-IV inhibitor | Unchanged (in RCTs) | Modest glucose control | Effect unknown | Cusi et al[9] |

| Vitamin E | Antioxidant | Not specified | Neutral | Improved (non-diabetics) | Cusi et al[9] |

| Obeticholic acid | FXR agonist | Not specified | Raises LDL, pruritus | Improved (fibrosis) | Lin et al[92]; Marek and Malhi[161] |

| Elafibranor | PPAR-α/δ agonist | Not specified | Improves lipids | Improved | Lin et al[160]; Marek and Malhi[161] |

| Cenicriviroc | CCR2/CCR5 antagonist | Not specified | Neutral | Improved | Lin et al[160]; Marek and Malhi[161] |

| Aramchol | SCD1 inhibitor | Not specified | Neutral | Improved | Lin et al[160]; Marek and Malhi[161] |

| Selonsertib | ASK1 inhibitor | Not specified | Neutral | Improved | Marek and Malhi[161] |

| Resmetirom | THR-β agonist | Not specified | Neutral | Improved | Marek and Malhi[161] |

| Tirzepatide | GLP-1/GIP RA | Decreased | Weight loss, metabolic improvement | Improved | Handu et al[162] |

| Survodutide | GLP-1/glucagon RA | Not specified | Weight loss | Improved | Handu et al[162] |

| FGF-21 analogues | FGF-21 mimetic | Decreased | Improves lipid and glucose metabolism | Improved | Lin et al[160]; Marek and Malhi[161] |

| THR-β agonists | Thyroid hormone receptor-β agonist | Decreased | Neutral | Improved | Lin et al[160]; Marek and Malhi[161] |

| Pan-PPAR agonists | Pan-PPAR agonist | Decreased | Improves lipids, insulin sensitivity | Improved | Lin et al[160]; Marek and Malhi[161] |

| Curcumin | Polyphenol | Not specified | Antioxidant effects | Improved | Handu et al[162] |

| Silymarin | Flavonoid | Not specified | Hepatoprotective | Improved | Handu et al[162] |

| Resveratrol | Polyphenol | Not specified | Antioxidant/anti-inflammatory | Improved | Handu et al[162] |

| Coffee | Dietary | Not specified | Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant | Improved | Handu et al[162] |

| Green tea | Catechin-rich beverage | Not specified | Anti-inflammatory | Improved | Handu et al[162] |

| Berberine | Plant alkaloid | Not specified | Improves insulin resistance | Improved | Handu et al[162] |

| Risk factor | Mechanism | Associated outcome |

| Insulin resistance | Promotes de novo lipogenesis and reduces fatty acid oxidation | Steatosis, progression to MASH |

| Visceral obesity | Pro-inflammatory adipokine secretion, lipotoxicity | Fibrosis progression, inflammation |

| Poor glycemic control | Increases oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction | Fibrosis, hepatocellular injury |

| Dyslipidemia | Elevated triglycerides and LDL lead to hepatocyte stress | Lipotoxicity, NASH progression |

| Hypertension | Induces endothelial dysfunction and chronic inflammation | Increased risk of fibrosis |

| Sedentary lifestyle | Reduces insulin sensitivity and promotes weight gain | Increased steatosis and metabolic burden |

| Genetic variants (e.g., PNPLA3, TM6SF2) | Impaired lipid export and processing | Accelerated fibrosis progression |

| Gut microbiota dysbiosis | Increased endotoxin (LPS) translocation and inflammation | Worsening hepatic inflammation and fibrosis |

| Advanced age | Reduced hepatic regeneration capacity, cumulative metabolic injury | Greater risk of advanced fibrosis |

| Diet high in saturated fats/fructose | Increases hepatic fat accumulation and lipotoxic intermediates | Steatohepatitis and fibrosis |

| Smoking | Oxidative stress and impaired insulin sensitivity | Fibrosis and cardiovascular risk |

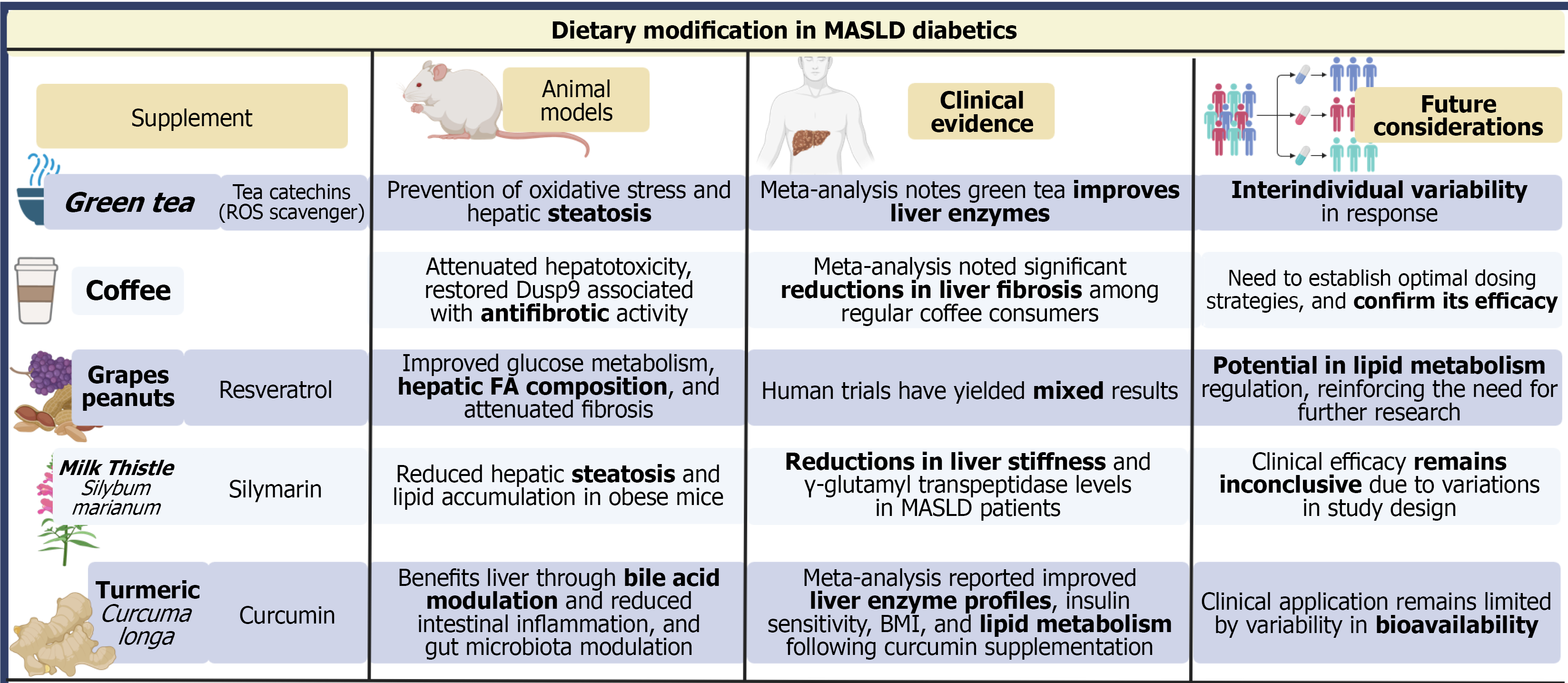

Lifestyle intervention remains a foundational element of MASLD therapy across all guidelines (Figure 3). Weight loss of 5%-10% improves steatosis and hepatic inflammation, while losses of ≥ 10% are associated with fibrosis regression[65-68]. Sustained improvement is most consistently achieved with combined dietary caloric restriction, aerobic activity, and resistance training[69-73]. However, adherence remains a major barrier, and multidisciplinary behavioral strategies, structured exercise programs, and dietitian-supported models enhance long-term success[74-79].

GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) improve glycemic control, reduce body weight, and lower hepatic fat content[80]. In the LEAN trial, liraglutide achieved higher rates of NASH (historical term) resolution compared with placebo (39% vs 9%), though fibrosis improvement was not statistically significant[81-83]. Semaglutide demonstrated dose-dependent NASH resolution rates (up to 59%) in a phase 2 trial but did not yield significant improvement in fibrosis stage[84-88].

GLP-1 RAs are FDA-approved for T2DM and obesity, with hepatic effects considered secondary metabolic benefits. They are not approved specifically for MASLD/MASH, and their role remains adjunctive, particularly in patients with T2DM, obesity, or high cardiovascular risk.

SGLT-2i reduce hepatic fat content and improve metabolic parameters. Clinical studies demonstrate reductions in aminotransferase levels and MRI-PDFF-quantified steatosis, with consistent glycemic and cardiometabolic benefits[89]. However, histologic evidence remains limited, and no significant antifibrotic effect has been conclusively demonstrated. Their clinical utility in MASLD is therefore tied primarily to management of coexisting T2DM[90-95].

Guidelines from the ADA, AASLD, and EASL recognize SGLT-2i as first-line therapy in T2DM with cardiovascular or renal risk, and their potential hepatic benefits provide an additional rationale for use in MASLD. Ongoing phase 3 studies, including DEAN and DAPA-liver, are expected to clarify their antifibrotic efficacy and establish their role in routine MASLD care[96-98].

As a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ agonist, pioglitazone improves insulin sensitivity and has consistently demonstrated histologic benefit in patients with biopsy-proven NASH (historical term), including im

Metformin improves insulin resistance and aminotransferase levels but does not improve histologic features of steatosis, ballooning, inflammation, or fibrosis in MASLD. It should not be used as targeted MASLD therapy but remains appropriate for glycemic management in patients with T2DM[109-116].

Dual incretin agonists such as tirzepatide have shown superior reductions in body weight, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis compared with GLP-1 monotherapy[117-119]. Early imaging-based data demonstrate robust reductions in liver fat, but no biopsy-based evidence of fibrosis improvement is yet available[120-122]. These agents are not MASLD-specific therapies and require further validation in histologic endpoints.

Resmetirom, a selective thyroid hormone receptor-β agonist, became the first FDA-approved therapy for noncirrhotic MASH with F2-F3 fibrosis in 2024. In the MAESTRO-NASH trial (conducted under historical NASH definitions), resmetirom achieved: (1) Significantly higher rates of NASH resolution without worsening fibrosis; (2) Significant fibrosis improvement without worsening NASH; and (3) Reductions in low density lipoprotein cholesterol and hepatic fat on MRI-PDFF[123,124].

Common adverse effects include mild gastrointestinal symptoms and transient changes in thyroid function markers. Long-term fibrosis and clinical outcome data remain under investigation. Although approved in the United States for noncirrhotic MASH with fibrosis, its generalizability to broader MASLD populations, particularly those without biopsy-confirmed disease, is still being defined.

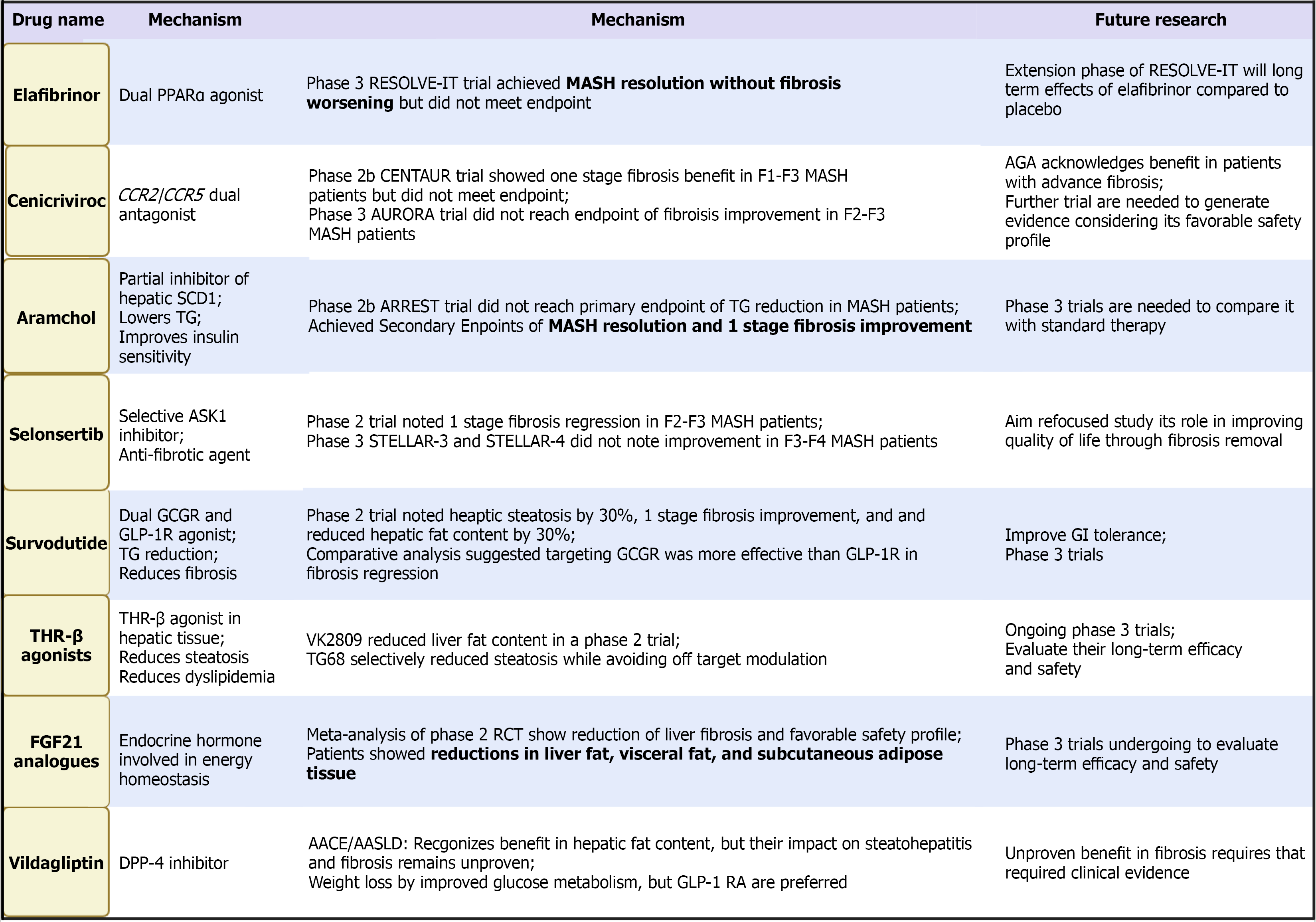

Farnesoid X receptor (FXR) agonists, including obeticholic acid, reduce bile acid synthesis and modulate hepatic inflammation and fibrosis pathways. Although early trials demonstrated improvements in fibrosis, pruritus and lipid changes posed safety concerns. Recent studies of newer, more selective FXR agonists aim to improve tolerability while maintaining efficacy[125-128].

Lanifibranor, a pan-PPAR agonist targeting PPAR-α/δ/γ, demonstrated significant improvements across multiple histologic domains, including fibrosis, in its phase 2 trial[129,130]. Phase 3 trials are ongoing to determine long-term and hard-outcome benefits.

Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) analogs pegozafermin (FGF21 analog) modulate hepatic lipid metabolism, inflammation, and fibrogenesis. Early trials show meaningful reductions in hepatic fat and improvements in metabolic markers, though fibrosis results remain mixed[131-133].

Aramchol reduces de novo lipogenesis and improves hepatic fat metabolism. Early trials demonstrated reductions in liver fat and markers of inflammation, but large-scale fibrosis outcomes remain inconclusive[134-136].

Additional agents, including surfodutide and apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 inhibitors, are in early-phase development and target pathways involved in inflammation or energy homeostasis[137-139]. Their eventual role will depend on histologic efficacy and long-term safety.

Aldafermin (NGM282) is an analog of FGF19, a regulator of bile acid synthesis and glucose metabolism. It reduces hepatic steatosis and inflammation via FXR-independent pathways. Short-term trials have shown significant reductions in liver fat content and liver enzyme levels, though improvements in fibrosis have been inconsistent[140-143]. Figure 4 highlights the emerging medications with potential benefit in patients with MASLD and T2DM.

Given the multifaceted pathophysiology of MASLD spanning steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis combination therapy is increasingly recognized as a rational and potentially more effective approach. Targeting multiple pathways simultaneously may amplify therapeutic benefits and mitigate the limitations of monotherapy[1,144]. Ongoing trials are evaluating combinations of GLP-1 RAs with FXR agonists, SGLT-2is with PPAR agonists, and metabolic modulators like resmetirom with antifibrotic agents. Such regimens aim to achieve greater histologic improvement while enhancing tolerability and adherence (Table 3)[124,145]. In the context of T2DM, combination therapy must also consider drug-drug interactions, glycemic variability, and patient-specific comorbidities. As precision medicine evolves, tailored combination strategies may become the norm, offering more individualized and effective care[146,147].

| Year | Trial | Drug/class | Primary endpoint | Key outcome | Ref. |

| 2015 | LEAN | Liraglutide (GLP-1 RA) | NASH resolution without fibrosis worsening | Met endpoint; improved NASH resolution | Armstrong et al[84] |

| 2019 | REGENERATE (Interim) | Obeticholic acid (FXR agonist) | Fibrosis improvement without NASH worsening | Improved fibrosis in 23% vs 12% placebo | Ratziu et al[163] |

| 2020 | REVERSE | Lanifibranor (pan-PPAR agonist) | Improvement in NAS and fibrosis | Significant histologic improvement | Francque et al[129] |

| 2021 | FLINT | Obeticholic acid | NAS improvement ≥ 2 points without fibrosis worsening | Positive results in steatosis and inflammation | Sanyal et al[164] |

| 2022 | MAESTRO-NAFLD-1 | Resmetirom (THR-β agonist) | Liver fat reduction via MRI-PDFF | Significant reduction in liver fat content | Harrison et al[165] |

| 2022 | MAESTRO-NASH | Resmetirom (THR-β agonist) | NASH resolution and fibrosis improvement | Met both primary endpoints | Harrison et al[123] |

| 2022 | SYNERGY | Semaglutide + cagrilintide | Liver fat reduction | Significant additive effect on steatosis | Frias et al[166] |

| 2023 | SURMOUNT-1 | Tirzepatide (GLP-1/GLP RA) | Weight reduction | Robust weight loss and decrease liver fat (MRI) | Loomba et al[117] |

| 2023 | ESSENCE | Efruxifermin (FGF-21 analogue) | Histologic NASH resolution and fibrosis improvement | Positive early-phase results | Harrison et al[133] |

| 2023 | CENTURION | Survodutide (GLP-1/glucagon RA) | Liver fat reduction | Marked liver fat loss on imaging | Sanyal et al[139] |

Therapeutic options for MASLD are expanding rapidly. Lifestyle modification remains foundational, while pharmacologic therapy is increasingly informed by metabolic comorbidities and fibrosis severity. Resmetirom represents a major step forward as the first approved therapy targeting underlying disease biology. GLP-1 RAs, SGLT-2is, and emerging incretin-based therapies offer metabolic and hepatic benefits but require further validation for fibrosis outcomes. As the therapeutic landscape evolves, integration of noninvasive markers, genetic profiling, and combination approaches may support more individualized and effective treatment strategies. Therapeutic response remains heterogeneous, particularly between individuals with and without T2DM, underscoring the need for individualized risk stratification.

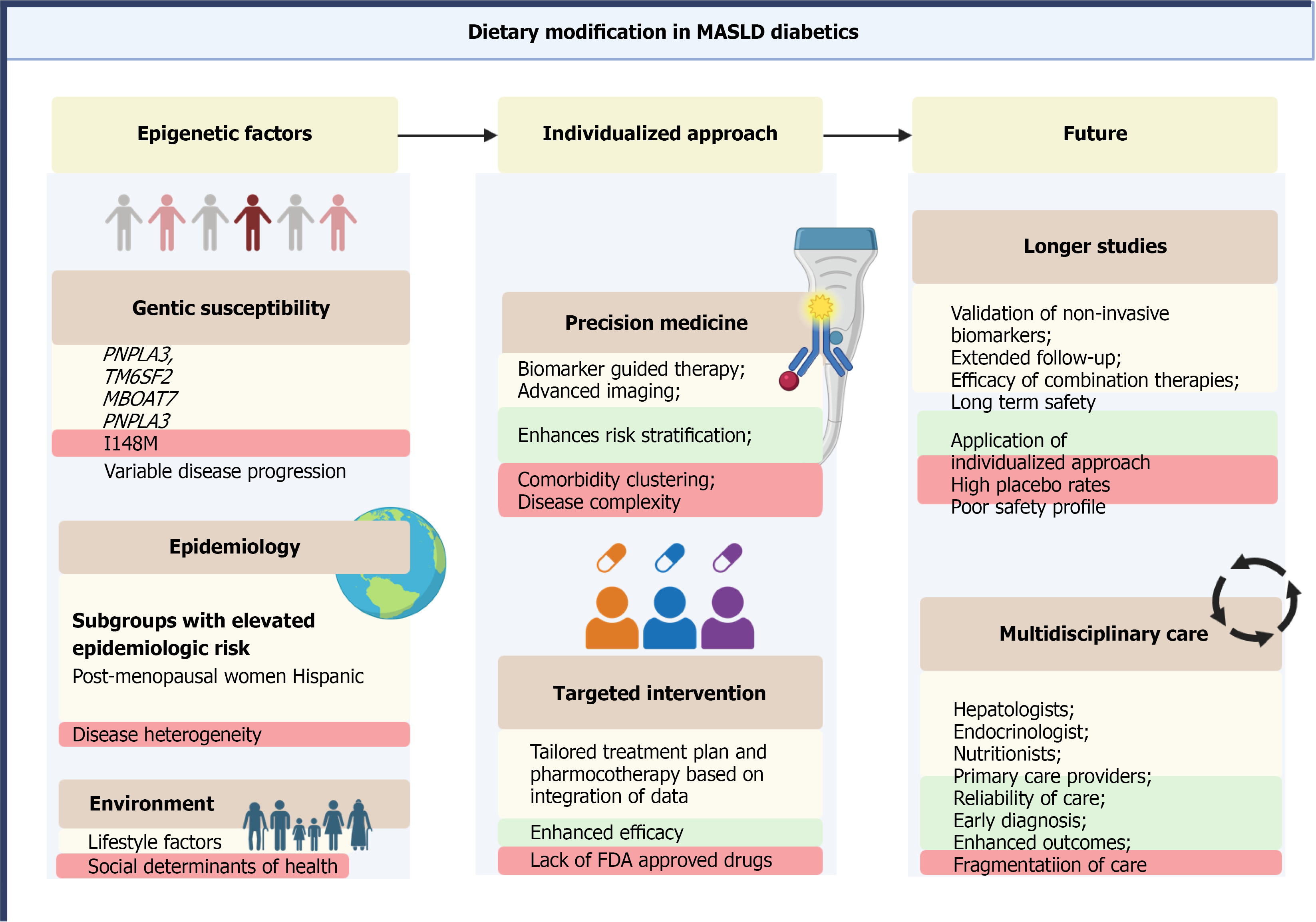

Personalized medicine is increasingly shaping the management of MASLD, particularly in individuals with T2DM, where disease expression, metabolic drivers, and treatment responsiveness vary substantially. Given this heterogeneity, individualized approaches based on genetic, metabolic, phenotypic, and behavioral factors are essential for optimizing outcomes.

Genetic polymorphisms strongly influence susceptibility to MASLD and its rate of progression. Variants in PNPLA3 (I148M), TM6SF2 (E167K), MBOAT7, and GCKR are associated with greater hepatic steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis. PNPLA3 is the most extensively studied and has been linked not only to heightened disease risk but also to reduced responsiveness to lifestyle and pharmacologic interventions. Integration of genotyping into clinical pathways may enhance risk stratification and identify individuals most likely to benefit from early or targeted treatment.

Epigenetic mechanisms such as DNA methylation and non-coding RNA expression further modify disease phenotype and therapeutic response. Biomarkers including miR-122 and miR-34a, along with emerging methylation signatures, show promise for predicting disease activity and may support future precision-based therapeutic strategies[148-152].

Variation in MASLD severity and progression is also shaped by patient phenotype. Postmenopausal women and men appear to have higher fibrosis risk than premenopausal women, likely due to hormonal and metabolic differences. Ethnic disparities are well recognized; for example, Hispanic individuals have a higher prevalence and more aggressive MASLD phenotypes, partly driven by PNPLA3 prevalence and adipose tissue distribution[153]. These demographic and phenotypic differences underscore the need for tailored clinical approaches rather than uniform management.

Advances in metabolomics, lipidomics, and proteomics have identified distinct molecular signatures associated with steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis. Lipid species, bile acid profiles, and inflammatory protein signatures correlate with fibrosis stage and metabolic dysfunction, offering insights into individualized pathophysiology and potential therapeutic targeting[154].

Non-invasive diagnostics including transient elastography, MRI-based techniques, and blood-based fibrosis panels support individualized risk prediction and longitudinal monitoring. Composite algorithms that merge imaging, serologic markers, and genomic data are in active development and may eventually guide the timing and intensity of therapeutic intervention[1,155]. Such tools may reduce unnecessary biopsies and support precision-based follow-up strategies.

Personalized therapy selection is particularly relevant in MASLD with T2DM. Glucose-lowering medications should be chosen based on comorbidities, cardiovascular and renal risk, obesity status, and patient preference. Examples include: (1) GLP-1 RAs for individuals with obesity and established cardiovascular disease; (2) SGLT-2is for patients with chronic kidney disease or heart failure; and (3) MASLD-targeted agents (e.g., resmetirom) for individuals with biopsy-confirmed disease and fibrosis, where indicated. Response to therapy is known to be heterogeneous, emphasizing the need for flexible, individualized treatment strategies rather than a one-size-fits-all approach.

Digital health platforms and artificial intelligence (AI) are advancing the ability to personalize MASLD management. Machine-learning models applied to electronic health records, imaging repositories, and wearable sensor data can help identify high-risk individuals, predict fibrosis trajectories, and support clinical decision-making with greater accuracy[156-159].

Personalized medicine represents a critical evolution in MASLD management. Aligning therapeutic decisions with individual genetic, metabolic, phenotypic, and behavioral profiles may improve treatment response, minimize progression, and create a more patient-centered model of care. Continued development of integrated diagnostic algorithms and AI-enhanced tools will further refine precision strategies and improve clinical outcomes (Figure 5).

MASLD and T2DM represent intersecting global epidemics with substantial clinical and public health implications. MASLD affects the majority of individuals with T2DM and is associated with accelerated progression to advanced fibrosis, cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and increased cardiovascular mortality. This dual burden underscores the importance of routine liver health assessment within diabetes care and highlights the need for earlier identification of high-risk patients. Advances in non-invasive diagnostics including fibrosis scores, transient elastography, and MRI-based modalities have strengthened risk stratification; however, their accuracy is diminished in T2DM, where false-negative results are more common. Moreover, imaging biomarkers such as MRI-PDFF, although useful for assessing hepatic fat, are not validated surrogate endpoints for predicting fibrosis progression. Despite guideline-supported algorithms from the ADA, AASLD, and EASL, real-world implementation remains inconsistent. Integrating MASLD screening into primary diabetes workflows, supported by electronic health record-based prompts and structured referral pathways, may improve detection and standardization. Lifestyle modification remains a foundational element of therapy, though long-term adherence challenges limit durability. Several glucose-lowering agents including GLP-1 RAs, SGLT-2is, and pioglitazone demonstrate metabolic and hepatic benefits, but most supporting evidence derives from studies conducted under historical NAFLD/NASH definitions and in mixed populations. Resmetirom represents a meaningful advancement as the first FDA-approved therapy for noncirrhotic MASH with fibrosis in the United States, yet its long-term outcomes and applicability across diverse MASLD phenotypes require further study. Emerging agents such as thyroid hormone receptor-β agonists, dual and multi-agonist incretin therapies, FGF analogs, and pan-PPAR modulators show promise, but validation in T2DM-enriched cohorts and across demographic subgroups remains essential. Future efforts should prioritize the validation of non-invasive biomarkers against long-term clinical outcomes, comparative effectiveness studies of pharmacologic agents specifically in T2DM, and integration of MASLD-directed therapy into broader cardiometabolic risk reduction frameworks. Precision medicine approaches incorporating genetic variants (e.g., PNPLA3), metabolomic signatures, and individualized metabolic profiles may refine patient selection and therapeutic strategies. Special populations including children, individuals with type 1 diabetes, and women with gestational diabetes remain significantly understudied and warrant focused investigation. Ultimately, improving MASLD outcomes in T2DM requires reframing the disease as a systemic metabolic disorder rather than a liver-specific condition. Coordinated care involving hepatology, endocrinology, cardiology, and primary care will be essential to translate ongoing advances in diagnostics and therapeutics into meaningful clinical benefit. The coming decade offers the opportunity to shift from under-recognition and fragmented management toward integrated, evidence-based, multidisciplinary care capable of altering the natural history of this increasingly prevalent condition.

| 1. | American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 4. Comprehensive Medical Evaluation and Assessment of Comorbidities: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2025. Diabetes Care. 2025;48:S59-S85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 98.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Berdowska I, Matusiewicz M, Fecka I. A Comprehensive Review of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: Its Mechanistic Development Focusing on Methylglyoxal and Counterbalancing Treatment Strategies. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26:2394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Targher G, Bertolini L, Rodella S, Lippi G, Franchini M, Zoppini G, Muggeo M, Day CP. NASH predicts plasma inflammatory biomarkers independently of visceral fat in men. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16:1394-1399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yanai H, Adachi H, Hakoshima M, Iida S, Katsuyama H. Metabolic-Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease-Its Pathophysiology, Association with Atherosclerosis and Cardiovascular Disease, and Treatments. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:15473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Qi X, Li J, Caussy C, Teng GJ, Loomba R. Epidemiology, screening, and co-management of type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Hepatology. 2024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 50.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gancheva S, Roden M, Castera L. Diabetes as a risk factor for MASH progression. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2024;217:111846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Riley DR, Hydes T, Hernadez G, Zhao SS, Alam U, Cuthbertson DJ. The synergistic impact of type 2 diabetes and MASLD on cardiovascular, liver, diabetes-related and cancer outcomes. Liver Int. 2024;44:2538-2550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shah N, Sanyal AJ. A Pragmatic Management Approach for Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatosis and Steatohepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2025;120:75-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cusi K, Isaacs S, Barb D, Basu R, Caprio S, Garvey WT, Kashyap S, Mechanick JI, Mouzaki M, Nadolsky K, Rinella ME, Vos MB, Younossi Z. American Association of Clinical Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Primary Care and Endocrinology Clinical Settings: Co-Sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD). Endocr Pract. 2022;28:528-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 365] [Cited by in RCA: 674] [Article Influence: 168.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Sandireddy R, Sakthivel S, Gupta P, Behari J, Tripathi M, Singh BK. Systemic impacts of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) on heart, muscle, and kidney related diseases. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2024;12:1433857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Targher G, Byrne CD, Tilg H. MASLD: a systemic metabolic disorder with cardiovascular and malignant complications. Gut. 2024;73:691-702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 268] [Article Influence: 134.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Chan KE, Ong EYH, Chung CH, Ong CEY, Koh B, Tan DJH, Lim WH, Yong JN, Xiao J, Wong ZY, Syn N, Kaewdech A, Teng M, Wang JW, Chew N, Young DY, Know A, Siddiqui MS, Huang DQ, Tamaki N, Wong VW, Mantzoros CS, Sanyal A, Noureddin M, Ng CH, Muthiah M. Longitudinal Outcomes Associated With Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: A Meta-analysis of 129 Studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;22:488-498.e14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 39.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Byrne CD, Armandi A, Pellegrinelli V, Vidal-Puig A, Bugianesi E. Author Correction: Μetabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: a condition of heterogeneous metabolic risk factors, mechanisms and comorbidities requiring holistic treatment. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;22:734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Castera L, Garteiser P, Laouenan C, Vidal-Trécan T, Vallet-Pichard A, Manchon P, Paradis V, Czernichow S, Roulot D, Larger E, Pol S, Bedossa P, Correas JM, Valla D, Gautier JF, Van Beers BE; QUID NASH investigators. Prospective head-to-head comparison of non-invasive scores for diagnosis of fibrotic MASH in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Hepatol. 2024;81:195-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Caussy C, Vergès B, Leleu D, Duvillard L, Subtil F, Abichou-Klich A, Hervieu V, Milot L, Ségrestin B, Bin S, Rouland A, Delaunay D, Morcel P, Hadjadj S, Primot C, Petit JM, Charrière S, Moulin P, Levrero M, Cariou B, Disse E. Screening for Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease-Related Advanced Fibrosis in Diabetology: A Prospective Multicenter Study. Diabetes Care. 2025;48:877-886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Souza M, Al-Sharif L, Antunes VLJ, Huang DQ, Loomba R. Comparison of pharmacological therapies in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis for fibrosis regression and MASH resolution: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2025;82:1523-1533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 41.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sumida Y, Yoneda M, Tokushige K, Kawanaka M, Fujii H, Yoneda M, Imajo K, Takahashi H, Eguchi Y, Ono M, Nozaki Y, Hyogo H, Koseki M, Yoshida Y, Kawaguchi T, Kamada Y, Okanoue T, Nakajima A, Jsg-Nafld JSGON. Antidiabetic Therapy in the Treatment of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:1907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Koh B, Xiao J, Ng CH, Law M, Gunalan SZ, Danpanichkul P, Ramadoss V, Sim BKL, Tan EY, Teo CB, Nah B, Teng M, Wijarnpreecha K, Seko Y, Lim MC, Takahashi H, Nakajima A, Noureddin M, Muthiah M, Huang DQ, Loomba R. Comparative efficacy of pharmacologic therapies for MASH in reducing liver fat content: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2026;83:117-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Bansal SK, Bansal MB. Pathogenesis of MASLD and MASH - role of insulin resistance and lipotoxicity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2024;59 Suppl 1:S10-S22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 40.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Farrell GC, Haczeyni F, Chitturi S. Pathogenesis of NASH: How Metabolic Complications of Overnutrition Favour Lipotoxicity and Pro-Inflammatory Fatty Liver Disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018;1061:19-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Iturbe-Rey S, Maccali C, Arrese M, Aspichueta P, Oliveira CP, Castro RE, Lapitz A, Izquierdo-Sanchez L, Bujanda L, Perugorria MJ, Banales JM, Rodrigues PM. Lipotoxicity-driven metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). Atherosclerosis. 2025;400:119053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 34.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Hughey CC, Puchalska P, Crawford PA. Integrating the contributions of mitochondrial oxidative metabolism to lipotoxicity and inflammation in NAFLD pathogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2022;1867:159209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Venkatesan N, Doskey LC, Malhi H. The Role of Endoplasmic Reticulum in Lipotoxicity during Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD) Pathogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2023;193:1887-1899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hirsova P, Ibrabim SH, Gores GJ, Malhi H. Lipotoxic lethal and sublethal stress signaling in hepatocytes: relevance to NASH pathogenesis. J Lipid Res. 2016;57:1758-1770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Diehl AM, Day C. Cause, Pathogenesis, and Treatment of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2063-2072. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 671] [Cited by in RCA: 976] [Article Influence: 108.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Svegliati-Baroni G, Pierantonelli I, Torquato P, Marinelli R, Ferreri C, Chatgilialoglu C, Bartolini D, Galli F. Lipidomic biomarkers and mechanisms of lipotoxicity in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;144:293-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 26.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 27. | Abdelnabi MN, Hassan GS, Shoukry NH. Role of the type 3 cytokines IL-17 and IL-22 in modulating metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1437046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Mladenić K, Lenartić M, Marinović S, Polić B, Wensveen FM. The "Domino effect" in MASLD: The inflammatory cascade of steatohepatitis. Eur J Immunol. 2024;54:e2149641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kim HY, Rosenthal SB, Liu X, Miciano C, Hou X, Miller M, Buchanan J, Poirion OB, Chilin-Fuentes D, Han C, Housseini M, Carvalho-Gontijo Weber R, Sakane S, Lee W, Zhao H, Diggle K, Preissl S, Glass CK, Ren B, Wang A, Brenner DA, Kisseleva T. Multi-modal analysis of human hepatic stellate cells identifies novel therapeutic targets for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2025;82:882-897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Quinn C, Rico MC, Merali C, Barrero CA, Perez-Leal O, Mischley V, Karanicolas J, Friedman SL, Merali S. Secreted folate receptor γ drives fibrogenesis in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis by amplifying TGFβ signaling in hepatic stellate cells. Sci Transl Med. 2023;15:eade2966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kisseleva T, Ganguly S, Murad R, Wang A, Brenner DA. Regulation of Hepatic Stellate Cell Phenotypes in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2025;169:797-812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Lachowski D, Cortes E, Rice A, Pinato D, Rombouts K, Del Rio Hernandez A. Matrix stiffness modulates the activity of MMP-9 and TIMP-1 in hepatic stellate cells to perpetuate fibrosis. Sci Rep. 2019;9:7299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Tsutsumi T, Kawaguchi T, Fujii H, Kamada Y, Takahashi H, Kawanaka M, Sumida Y, Iwaki M, Hayashi H, Toyoda H, Oeda S, Hyogo H, Morishita A, Munekage K, Kawata K, Sawada K, Maeshiro T, Tobita H, Yoshida Y, Naito M, Araki A, Arakaki S, Noritake H, Ono M, Masaki T, Yasuda S, Tomita E, Yoneda M, Tokushige A, Ueda S, Aishima S, Nakajima A, Okanoue T. Hepatic inflammation and fibrosis are profiles related to mid-term mortality in biopsy-proven MASLD: A multicenter study in Japan. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2024;59:1559-1570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kobayashi T, Iwaki M, Nakajima A, Nogami A, Yoneda M. Current Research on the Pathogenesis of NAFLD/NASH and the Gut-Liver Axis: Gut Microbiota, Dysbiosis, and Leaky-Gut Syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:11689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Martín-Mateos R, Albillos A. The Role of the Gut-Liver Axis in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Front Immunol. 2021;12:660179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | An L, Wirth U, Koch D, Schirren M, Drefs M, Koliogiannis D, Nieß H, Andrassy J, Guba M, Bazhin AV, Werner J, Kühn F. The Role of Gut-Derived Lipopolysaccharides and the Intestinal Barrier in Fatty Liver Diseases. J Gastrointest Surg. 2022;26:671-683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 42.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Nawrot M, Peschard S, Lestavel S, Staels B. Intestine-liver crosstalk in Type 2 Diabetes and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism. 2021;123:154844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Bruneau A, Hundertmark J, Guillot A, Tacke F. Molecular and Cellular Mediators of the Gut-Liver Axis in the Progression of Liver Diseases. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:725390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Benedé-Ubieto R, Cubero FJ, Nevzorova YA. Breaking the barriers: the role of gut homeostasis in Metabolic-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD). Gut Microbes. 2024;16:2331460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 60.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Eslam M, Valenti L, Romeo S. Genetics and epigenetics of NAFLD and NASH: Clinical impact. J Hepatol. 2018;68:268-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 732] [Cited by in RCA: 725] [Article Influence: 90.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Carlsson B, Lindén D, Brolén G, Liljeblad M, Bjursell M, Romeo S, Loomba R. Review article: the emerging role of genetics in precision medicine for patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51:1305-1320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Dongiovanni P, Valenti L. Genetics of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism. 2016;65:1026-1037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Kimura M, Iguchi T, Iwasawa K, Dunn A, Thompson WL, Yoneyama Y, Chaturvedi P, Zorn AM, Wintzinger M, Quattrocelli M, Watanabe-Chailland M, Zhu G, Fujimoto M, Kumbaji M, Kodaka A, Gindin Y, Chung C, Myers RP, Subramanian GM, Hwa V, Takebe T. En masse organoid phenotyping informs metabolic-associated genetic susceptibility to NASH. Cell. 2022;185:4216-4232.e16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Moore MP, Wang X, Kennelly JP, Shi H, Ishino Y, Kano K, Aoki J, Cherubini A, Ronzoni L, Guo X, Chalasani NP, Khalid S, Saleheen D, Mitsche MA, Rotter JI, Yates KP, Valenti L, Kono N, Tontonoz P, Tabas I. Low MBOAT7 expression, a genetic risk for MASH, promotes a profibrotic pathway involving hepatocyte TAZ upregulation. Hepatology. 2025;81:576-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Krawczyk M, Rau M, Schattenberg JM, Bantel H, Pathil A, Demir M, Kluwe J, Boettler T, Lammert F, Geier A; NAFLD Clinical Study Group. Combined effects of the PNPLA3 rs738409, TM6SF2 rs58542926, and MBOAT7 rs641738 variants on NAFLD severity: a multicenter biopsy-based study. J Lipid Res. 2017;58:247-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Wattacheril JJ, Abdelmalek MF, Lim JK, Sanyal AJ. AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Role of Noninvasive Biomarkers in the Evaluation and Management of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:1080-1088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 46.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Yip TC, Lee HW, Lin H, Tsochatzis E, Petta S, Bugianesi E, Yoneda M, Zheng MH, Hagström H, Boursier J, Calleja JL, Goh GB, Chan WK, Gallego-Durán R, Sanyal AJ, de Lédinghen V, Newsome PN, Fan JG, Castéra L, Lai M, Fournier-Poizat C, Wong GL, Pennisi G, Armandi A, Nakajima A, Liu WY, Shang Y, de Saint-Loup M, Llop E, Teh KKJ, Lara-Romero C, Asgharpour A, Mahgoub S, Chan MS, Canivet CM, Romero-Gomez M, Kim SU, Wong VW. Prognostic performance of the two-step clinical care pathway in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2025;83:304-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Mózes FE, Lee JA, Selvaraj EA, Jayaswal ANA, Trauner M, Boursier J, Fournier C, Staufer K, Stauber RE, Bugianesi E, Younes R, Gaia S, Lupșor-Platon M, Petta S, Shima T, Okanoue T, Mahadeva S, Chan WK, Eddowes PJ, Hirschfield GM, Newsome PN, Wong VW, de Ledinghen V, Fan J, Shen F, Cobbold JF, Sumida Y, Okajima A, Schattenberg JM, Labenz C, Kim W, Lee MS, Wiegand J, Karlas T, Yılmaz Y, Aithal GP, Palaniyappan N, Cassinotto C, Aggarwal S, Garg H, Ooi GJ, Nakajima A, Yoneda M, Ziol M, Barget N, Geier A, Tuthill T, Brosnan MJ, Anstee QM, Neubauer S, Harrison SA, Bossuyt PM, Pavlides M; LITMUS Investigators. Diagnostic accuracy of non-invasive tests for advanced fibrosis in patients with NAFLD: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Gut. 2022;71:1006-1019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 346] [Cited by in RCA: 352] [Article Influence: 88.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 49. | Singh A, Gosai F, Siddiqui MT, Gupta M, Lopez R, Lawitz E, Poordad F, Carey W, McCullough A, Alkhouri N. Accuracy of Noninvasive Fibrosis Scores to Detect Advanced Fibrosis in Patients With Type-2 Diabetes With Biopsy-proven Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020;54:891-897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Pennisi G, Enea M, Falco V, Aithal GP, Palaniyappan N, Yilmaz Y, Boursier J, Cassinotto C, de Lédinghen V, Chan WK, Mahadeva S, Eddowes P, Newsome P, Karlas T, Wiegand J, Wong VW, Schattenberg JM, Labenz C, Kim W, Lee MS, Lupsor-Platon M, Cobbold JFL, Fan JG, Shen F, Staufer K, Trauner M, Stauber R, Nakajima A, Yoneda M, Bugianesi E, Younes R, Gaia S, Zheng MH, Cammà C, Anstee QM, Mózes FE, Pavlides M, Petta S. Noninvasive assessment of liver disease severity in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and type 2 diabetes. Hepatology. 2023;78:195-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Park CC, Nguyen P, Hernandez C, Bettencourt R, Ramirez K, Fortney L, Hooker J, Sy E, Savides MT, Alquiraish MH, Valasek MA, Rizo E, Richards L, Brenner D, Sirlin CB, Loomba R. Magnetic Resonance Elastography vs Transient Elastography in Detection of Fibrosis and Noninvasive Measurement of Steatosis in Patients With Biopsy-Proven Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:598-607.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 479] [Cited by in RCA: 569] [Article Influence: 63.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Imajo K, Kessoku T, Honda Y, Tomeno W, Ogawa Y, Mawatari H, Fujita K, Yoneda M, Taguri M, Hyogo H, Sumida Y, Ono M, Eguchi Y, Inoue T, Yamanaka T, Wada K, Saito S, Nakajima A. Magnetic Resonance Imaging More Accurately Classifies Steatosis and Fibrosis in Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Than Transient Elastography. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:626-637.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 495] [Cited by in RCA: 627] [Article Influence: 62.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Selvaraj EA, Mózes FE, Jayaswal ANA, Zafarmand MH, Vali Y, Lee JA, Levick CK, Young LAJ, Palaniyappan N, Liu CH, Aithal GP, Romero-Gómez M, Brosnan MJ, Tuthill TA, Anstee QM, Neubauer S, Harrison SA, Bossuyt PM, Pavlides M; LITMUS Investigators. Diagnostic accuracy of elastography and magnetic resonance imaging in patients with NAFLD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hepatol. 2021;75:770-785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 250] [Article Influence: 50.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 54. | Nogami A, Yoneda M, Iwaki M, Kobayashi T, Kessoku T, Honda Y, Ogawa Y, Imajo K, Higurashi T, Hosono K, Kirikoshi H, Saito S, Nakajima A. Diagnostic comparison of vibration-controlled transient elastography and MRI techniques in overweight and obese patients with NAFLD. Sci Rep. 2022;12:21925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Kanwal F, Shubrook JH, Adams LA, Pfotenhauer K, Wai-Sun Wong V, Wright E, Abdelmalek MF, Harrison SA, Loomba R, Mantzoros CS, Bugianesi E, Eckel RH, Kaplan LM, El-Serag HB, Cusi K. Clinical Care Pathway for the Risk Stratification and Management of Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:1657-1669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 440] [Article Influence: 88.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Vilar-Gomez E, Chalasani N. Non-invasive assessment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Clinical prediction rules and blood-based biomarkers. J Hepatol. 2018;68:305-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 331] [Cited by in RCA: 465] [Article Influence: 58.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Bril F, McPhaul MJ, Caulfield MP, Clark VC, Soldevilla-Pico C, Firpi-Morell RJ, Lai J, Shiffman D, Rowland CM, Cusi K. Performance of Plasma Biomarkers and Diagnostic Panels for Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis and Advanced Fibrosis in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:290-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 23.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Bedossa P. Diagnosis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease/non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: Why liver biopsy is essential. Liver Int. 2018;38 Suppl 1:64-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Bedossa P, Patel K. Biopsy and Noninvasive Methods to Assess Progression of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1811-1822.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Tapper EB, Lok AS. Use of Liver Imaging and Biopsy in Clinical Practice. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:756-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 302] [Article Influence: 33.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Lim JK, Flamm SL, Singh S, Falck-Ytter YT; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on the Role of Elastography in the Evaluation of Liver Fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1536-1543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Konings LAM, Miguelañez-Matute L, Boeren AMP, van de Luitgaarden IAT, Dirksmeier F, de Knegt RJ, Tushuizen ME, Grobbee DE, Holleboom AG, Cabezas MC. Pharmacological treatment options for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. Eur J Clin Invest. 2025;55:e70003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Huttasch M, Roden M, Kahl S. Obesity and MASLD: Is weight loss the (only) key to treat metabolic liver disease? Metabolism. 2024;157:155937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 41.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Zhang X, Lau HC, Yu J. Pharmacological treatment for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and related disorders: Current and emerging therapeutic options. Pharmacol Rev. 2025;77:100018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 34.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Zeng XF, Varady KA, Wang XD, Targher G, Byrne CD, Tayyem R, Latella G, Bergheim I, Valenzuela R, George J, Newberry C, Zheng JS, George ES, Spearman CW, Kontogianni MD, Ristic-Medic D, Peres WAF, Depboylu GY, Yang W, Chen X, Rosqvist F, Mantzoros CS, Valenti L, Yki-Järvinen H, Mosca A, Sookoian S, Misra A, Yilmaz Y, Kim W, Fouad Y, Sebastiani G, Wong VW, Åberg F, Wong YJ, Zhang P, Bermúdez-Silva FJ, Ni Y, Lupsor-Platon M, Chan WK, Méndez-Sánchez N, de Knegt RJ, Alam S, Treeprasertsuk S, Wang L, Du M, Zhang T, Yu ML, Zhang H, Qi X, Liu X, Pinyopornpanish K, Fan YC, Niu K, Jimenez-Chillaron JC, Zheng MH. The role of dietary modification in the prevention and management of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: An international multidisciplinary expert consensus. Metabolism. 2024;161:156028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 37.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Beygi M, Ahi S, Zolghadri S, Stanek A. Management of Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease/Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: From Medication Therapy to Nutritional Interventions. Nutrients. 2024;16:2220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Vilar-Gomez E, Martinez-Perez Y, Calzadilla-Bertot L, Torres-Gonzalez A, Gra-Oramas B, Gonzalez-Fabian L, Friedman SL, Diago M, Romero-Gomez M. Weight Loss Through Lifestyle Modification Significantly Reduces Features of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:367-78.e5; quiz e14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1181] [Cited by in RCA: 1774] [Article Influence: 161.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 68. | Bagnato CB, Bianco A, Bonfiglio C, Franco I, Verrelli N, Carella N, Shahini E, Zappimbulso M, Giannuzzi V, Pesole PL, Ancona A, Giannelli G. Healthy Lifestyle Changes Improve Cortisol Levels and Liver Steatosis in MASLD Patients: Results from a Randomized Clinical Trial. Nutrients. 2024;16:4225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Ryan MC, Itsiopoulos C, Thodis T, Ward G, Trost N, Hofferberth S, O'Dea K, Desmond PV, Johnson NA, Wilson AM. The Mediterranean diet improves hepatic steatosis and insulin sensitivity in individuals with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2013;59:138-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 578] [Cited by in RCA: 559] [Article Influence: 43.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Gepner Y, Shelef I, Komy O, Cohen N, Schwarzfuchs D, Bril N, Rein M, Serfaty D, Kenigsbuch S, Zelicha H, Yaskolka Meir A, Tene L, Bilitzky A, Tsaban G, Chassidim Y, Sarusy B, Ceglarek U, Thiery J, Stumvoll M, Blüher M, Stampfer MJ, Rudich A, Shai I. The beneficial effects of Mediterranean diet over low-fat diet may be mediated by decreasing hepatic fat content. J Hepatol. 2019;71:379-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Baratta F, Pastori D, Polimeni L, Bucci T, Ceci F, Calabrese C, Ernesti I, Pannitteri G, Violi F, Angelico F, Del Ben M. Adherence to Mediterranean Diet and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Effect on Insulin Resistance. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1832-1839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Kawaguchi T, Charlton M, Kawaguchi A, Yamamura S, Nakano D, Tsutsumi T, Zafer M, Torimura T. Effects of Mediterranean Diet in Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Meta-Regression Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Semin Liver Dis. 2021;41:225-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Angelidi AM, Papadaki A, Nolen-Doerr E, Boutari C, Mantzoros CS. The effect of dietary patterns on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease diagnosed by biopsy or magnetic resonance in adults: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Metabolism. 2022;129:155136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Stine JG, Niccum BA, Zimmet AN, Intagliata N, Caldwell SH, Argo CK, Northup PG. Increased risk of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis due to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2018;9:140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Bacchi E, Negri C, Targher G, Faccioli N, Lanza M, Zoppini G, Zanolin E, Schena F, Bonora E, Moghetti P. Both resistance training and aerobic training reduce hepatic fat content in type 2 diabetic subjects with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (the RAED2 Randomized Trial). Hepatology. 2013;58:1287-1295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Delahanty LM. Weight loss in the prevention and treatment of diabetes. Prev Med. 2017;104:120-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Lazo M, Solga SF, Horska A, Bonekamp S, Diehl AM, Brancati FL, Wagenknecht LE, Pi-Sunyer FX, Kahn SE, Clark JM; Fatty Liver Subgroup of the Look AHEAD Research Group. Effect of a 12-month intensive lifestyle intervention on hepatic steatosis in adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2156-2163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 270] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Blonde L, Umpierrez GE, Reddy SS, McGill JB, Berga SL, Bush M, Chandrasekaran S, DeFronzo RA, Einhorn D, Galindo RJ, Gardner TW, Garg R, Garvey WT, Hirsch IB, Hurley DL, Izuora K, Kosiborod M, Olson D, Patel SB, Pop-Busui R, Sadhu AR, Samson SL, Stec C, Tamborlane WV Jr, Tuttle KR, Twining C, Vella A, Vellanki P, Weber SL. American Association of Clinical Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline: Developing a Diabetes Mellitus Comprehensive Care Plan-2022 Update. Endocr Pract. 2022;28:923-1049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 289] [Article Influence: 72.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Moncrieft AE, Llabre MM, McCalla JR, Gutt M, Mendez AJ, Gellman MD, Goldberg RB, Schneiderman N. Effects of a Multicomponent Life-Style Intervention on Weight, Glycemic Control, Depressive Symptoms, and Renal Function in Low-Income, Minority Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: Results of the Community Approach to Lifestyle Modification for Diabetes Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychosom Med. 2016;78:851-860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Rinella ME, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Siddiqui MS, Abdelmalek MF, Caldwell S, Barb D, Kleiner DE, Loomba R. AASLD Practice Guidance on the clinical assessment and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2023;77:1797-1835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1465] [Cited by in RCA: 1570] [Article Influence: 523.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 81. | Armstrong MJ, Hull D, Guo K, Barton D, Hazlehurst JM, Gathercole LL, Nasiri M, Yu J, Gough SC, Newsome PN, Tomlinson JW. Glucagon-like peptide 1 decreases lipotoxicity in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. 2016;64:399-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 343] [Article Influence: 34.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Newsome PN, Buchholtz K, Cusi K, Linder M, Okanoue T, Ratziu V, Sanyal AJ, Sejling AS, Harrison SA; NN9931-4296 Investigators. A Placebo-Controlled Trial of Subcutaneous Semaglutide in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1113-1124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 513] [Cited by in RCA: 1397] [Article Influence: 279.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Ghosal S, Datta D, Sinha B. A meta-analysis of the effects of glucagon-like-peptide 1 receptor agonist (GLP1-RA) in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) with type 2 diabetes (T2D). Sci Rep. 2021;11:22063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Armstrong MJ, Gaunt P, Aithal GP, Barton D, Hull D, Parker R, Hazlehurst JM, Guo K; LEAN trial team, Abouda G, Aldersley MA, Stocken D, Gough SC, Tomlinson JW, Brown RM, Hübscher SG, Newsome PN. Liraglutide safety and efficacy in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (LEAN): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. Lancet. 2016;387:679-690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1100] [Cited by in RCA: 1588] [Article Influence: 158.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 85. | Liao C, Liang X, Zhang X, Li Y. The effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists on visceral fat and liver ectopic fat in an adult population with or without diabetes and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0289616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Alkhouri N, Charlton M, Gray M, Noureddin M. The pleiotropic effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis: a review for gastroenterologists. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2025;34:169-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Das SR, Everett BM, Birtcher KK, Brown JM, Januzzi JL Jr, Kalyani RR, Kosiborod M, Magwire M, Morris PB, Neumiller JJ, Sperling LS. 2020 Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on Novel Therapies for Cardiovascular Risk Reduction in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:1117-1145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 374] [Cited by in RCA: 342] [Article Influence: 57.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Liu L, Chen J, Wang L, Chen C, Chen L. Association between different GLP-1 receptor agonists and gastrointestinal adverse reactions: A real-world disproportionality study based on FDA adverse event reporting system database. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:1043789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Bellanti F, Lo Buglio A, Dobrakowski M, Kasperczyk A, Kasperczyk S, Aich P, Singh SP, Serviddio G, Vendemiale G. Impact of sodium glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors on liver steatosis/fibrosis/inflammation and redox balance in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:3243-3257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Borisov AN, Kutz A, Christ ER, Heim MH, Ebrahimi F. Canagliflozin and Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease in Patients With Diabetes Mellitus: New Insights From CANVAS. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;108:2940-2949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Ala M. SGLT2 Inhibition for Cardiovascular Diseases, Chronic Kidney Disease, and NAFLD. Endocrinology. 2021;162:bqab157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Lin XF, Cui XN, Yang J, Jiang YF, Wei TJ, Xia L, Liao XY, Li F, Wang DD, Li J, Wu Q, Yin DS, Le YY, Yang K, Wei R, Hong TP. SGLT2 inhibitors ameliorate NAFLD in mice via downregulating PFKFB3, suppressing glycolysis and modulating macrophage polarization. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2024;45:2579-2597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Ong Lopez AMC, Pajimna JAT. Efficacy of sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors on hepatic fibrosis and steatosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2024;14:2122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Jin Z, Yuan Y, Zheng C, Liu S, Weng H. Effects of sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors on liver fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: An updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Diabetes Complications. 2023;37:108558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Ogawa Y, Nakahara T, Ando Y, Yamaoka K, Fujii Y, Uchikawa S, Fujino H, Ono A, Murakami E, Kawaoka T, Miki D, Yamauchi M, Tsuge M, Imamura M, Oka S. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors improve FibroScan-aspartate aminotransferase scores in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease complicated by type 2 diabetes. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;35:989-996. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Ao N, Du J, Jin S, Suo L, Yang J. The cellular and molecular mechanisms mediating the protective effects of sodium-glucose linked transporter 2 inhibitors against metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2025;27:457-467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Yanai H, Hakoshima M, Adachi H, Katsuyama H. Multi-Organ Protective Effects of Sodium Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:4416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Androutsakos T, Nasiri-Ansari N, Bakasis AD, Kyrou I, Efstathopoulos E, Randeva HS, Kassi E. SGLT-2 Inhibitors in NAFLD: Expanding Their Role beyond Diabetes and Cardioprotection. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:3107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Gastaldelli A, Sabatini S, Carli F, Gaggini M, Bril F, Belfort-DeAguiar R, Positano V, Barb D, Kadiyala S, Harrison S, Cusi K. PPAR-γ-induced changes in visceral fat and adiponectin levels are associated with improvement of steatohepatitis in patients with NASH. Liver Int. 2021;41:2659-2670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Cusi K, Orsak B, Bril F, Lomonaco R, Hecht J, Ortiz-Lopez C, Tio F, Hardies J, Darland C, Musi N, Webb A, Portillo-Sanchez P. Long-Term Pioglitazone Treatment for Patients With Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis and Prediabetes or Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomized Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:305-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 592] [Cited by in RCA: 769] [Article Influence: 76.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Musso G, Cassader M, Paschetta E, Gambino R. Thiazolidinediones and Advanced Liver Fibrosis in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:633-640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 242] [Cited by in RCA: 360] [Article Influence: 40.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Belfort R, Harrison SA, Brown K, Darland C, Finch J, Hardies J, Balas B, Gastaldelli A, Tio F, Pulcini J, Berria R, Ma JZ, Dwivedi S, Havranek R, Fincke C, DeFronzo R, Bannayan GA, Schenker S, Cusi K. A placebo-controlled trial of pioglitazone in subjects with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2297-2307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1307] [Cited by in RCA: 1349] [Article Influence: 67.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 103. | Alam F, Islam MA, Mohamed M, Ahmad I, Kamal MA, Donnelly R, Idris I, Gan SH. Efficacy and Safety of Pioglitazone Monotherapy in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Sci Rep. 2019;9:5389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Sinha B, Ghosal S. Assessing the need for pioglitazone in the treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of its risks and benefits from prospective trials. Sci Rep. 2020;10:15781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Guru B, Tamrakar AK, Manjula SN, Prashantha Kumar BR. Novel dual PPARα/γ agonists protect against liver steatosis and improve insulin sensitivity while avoiding side effects. Eur J Pharmacol. 2022;935:175322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | Abd El-Haleim EA, Bahgat AK, Saleh S. Effects of combined PPAR-γ and PPAR-α agonist therapy on fructose induced NASH in rats: Modulation of gene expression. Eur J Pharmacol. 2016;773:59-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |