Published online Jan 15, 2026. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v17.i1.113821

Revised: October 26, 2025

Accepted: December 3, 2025

Published online: January 15, 2026

Processing time: 132 Days and 16.1 Hours

Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome (RMS) is an extremely rare monogenic form of diabetes caused by mutations in the insulin receptor (INSR) gene, with only about 50 cases reported worldwide to date. Here, we report a case of RMS caused by a previously unreported c.1123+2 T>C splice mutation.

The patient was diagnosed with acanthosis nigricans and hypertrichosis at birth, and the growth rate was slower than that of normal children. At age 5, the patient had severe hyperinsulinemia, congenital heart abnormalities, and pineal cysts. At age 13, he was diagnosed with diabetes and exhibited symptoms of hyperinsulinemia, low body weight, growth retardation, acanthosis nigricans, dental ano

Genetic diagnosis is vital in RMS; c.1123+2 T>C mutation of INSR causes pancreatic decline; current treatments show limited effectiveness.

Core Tip: Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome is a rare monogenic diabetes caused by insulin receptor gene mutations, with no effective treatment currently available. Early diagnosis is essential for treatment planning and prognosis evaluation. We report a case of Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome where clinical features, whole-exome sequencing, and bioinformatics identified the c.1123+2 T>C mutation as likely pathogenic. Due to severe insulin resistance, a combination of oral hy

- Citation: Wang K, Zheng J, Gu LC, Li RR, Su XD, Bai J, Liao L. Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome caused by a novel splice-site mutation (c.1123+2 T>C) of insulin receptor: A case report and review of literature. World J Diabetes 2026; 17(1): 113821

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v17/i1/113821.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v17.i1.113821

Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome (RMS) is a monogenic type of diabetes that falls under the category of special types of diabetes[1]. The incidence of RMS is extremely low, with only scattered case reports found in the domestic and international literature. The first report of RMS dates back to 1956, when Rabson and Mendenhall described three siblings with this condition[2]. To date, we have reviewed only over 50 case reports of RMS[3]. It is a rare autosomal recessive genetic disorder caused by mutations in the insulin receptor (INSR) genes. Typical characteristics of RMS include severe insulin resistance in monogenic diabetes, including low birth weight, thickened nails, hypertrichosis, acanthosis nigricans (ANs), dental protrusion and dysplasia, polycystic ovaries, abdominal distension, penile enlargement, pineal cysts, and insulin-resistant diabetes[4-8]. This is the only insulin-resistant syndrome known to present with dental abnormalities.

Here, we report the case of a Chinese patient with classical manifestations of RMS resulting from a novel intronic mutation, INSR (NM_000208.4, c.1123+2 T>C). This novel intron mutation, located at the junction of exon 4 and intron 4, may cause variable splicing of INSR, ultimately resulting in the impaired function of INSR.

This report describes the case of a 13-year-old boy who had AN for 13 years and polyuria and polydipsia for 5 years.

In 2019, when the patient was 13 years old, he was scheduled for surgery due to “snoring during sleep for one year and enlarged tonsils for six months”. During hospitalization, elevated blood glucose levels were detected, and the patient was transferred to the endocrinology department for further examination. Glycated hemoglobin was 8.6%, and urinalysis showed glucose 3+ and ketone bodies 1+. Pancreatic function is detailed in Table 1. The 24-hour urine protein was 225.4 mg/24 hours and IGF-1 was 127.63 ng/mL. Tests for insulin autoantibody, islet cell cytoplasmic antibodies, and glutamic acid decarboxylase antibody were negative. Due to AN, severe insulin resistance, and malocclusion, the patient was diagnosed with RMS.

| Time | Fasting C-peptide (ng/mL) | Postprandial C-peptide (ng/mL) | Fasting insulin (IU/mL) | Postprandial insulin (IU/mL) | HbA1c | Urine sugar | Urine ketone bodies |

| 2011 | 8.09 | 25.32 | 272.4 | > 1000 | 5.6% | + | + |

| 2019 | 7.67 | 22.37 | 328.36 | 327.99 | 8.6% | 3+ | 4+ |

| 2022 | 7.17 | 20.2 | > 200 | > 200 | 13% | 4+ | 4+ |

| 2023 | 4.9 | 17.8 | > 200 | > 200 | 12.6% | 3+ | 4+ |

| 2024 | 4.5 | 16.7 | > 200 | > 200 | 11.2% | 3+ | 4+ |

| 2025 | 3.07 | 14.3 | > 200 | > 200 | 11.5% | 2+ | 3+ |

The patient’s parents were un-consanguineous. He was born at term (2006) with normal birth weight and length. At birth, he exhibited darkened skin and hypertrichosis primarily on the back of the neck and limbs. AN was observed on the neck, armpits, elbows, groin, navel, and popliteal fossa. In September 2011, at the age of 5 years, he was examined at Beijing Children’s Hospital, where an II/6 grade systolic murmur was heard over the precordium. Further examination revealed the blood glucose levels and pancreatic function (Table 1). Thyroid function, blood biochemistry, cortisol, adrenocorticotropic hormone, luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, prolactin, thyroglobulin antibody, thyroid peroxidase antibody, and thyrotropin receptor antibody levels were all within normal ranges. Cardiac ultrasonography revealed congenital heart defects, including a ventricular septal defect (subcritical) and atrial septal defect (ostium secundum). Pituitary magnetic resonance imaging suggested a pineal cyst, and abdominal and adrenal ultrasonography, adrenal computed tomography, and electrocardiogram showed no significant abnormalities. Diagnoses included: (1) AN; and (2) Congenital heart disease. No special treatment was administered at that time, as the child’s blood glucose level was not elevated.

The patient also had a younger brother. His parents and brothers did not have diabetes or any other hereditary diseases.

In 2019, his height was 150 cm (-2 SD), weight was 34.5 kg (-2 SD) and body mass index was 15.3 kg/m2. Physical exa

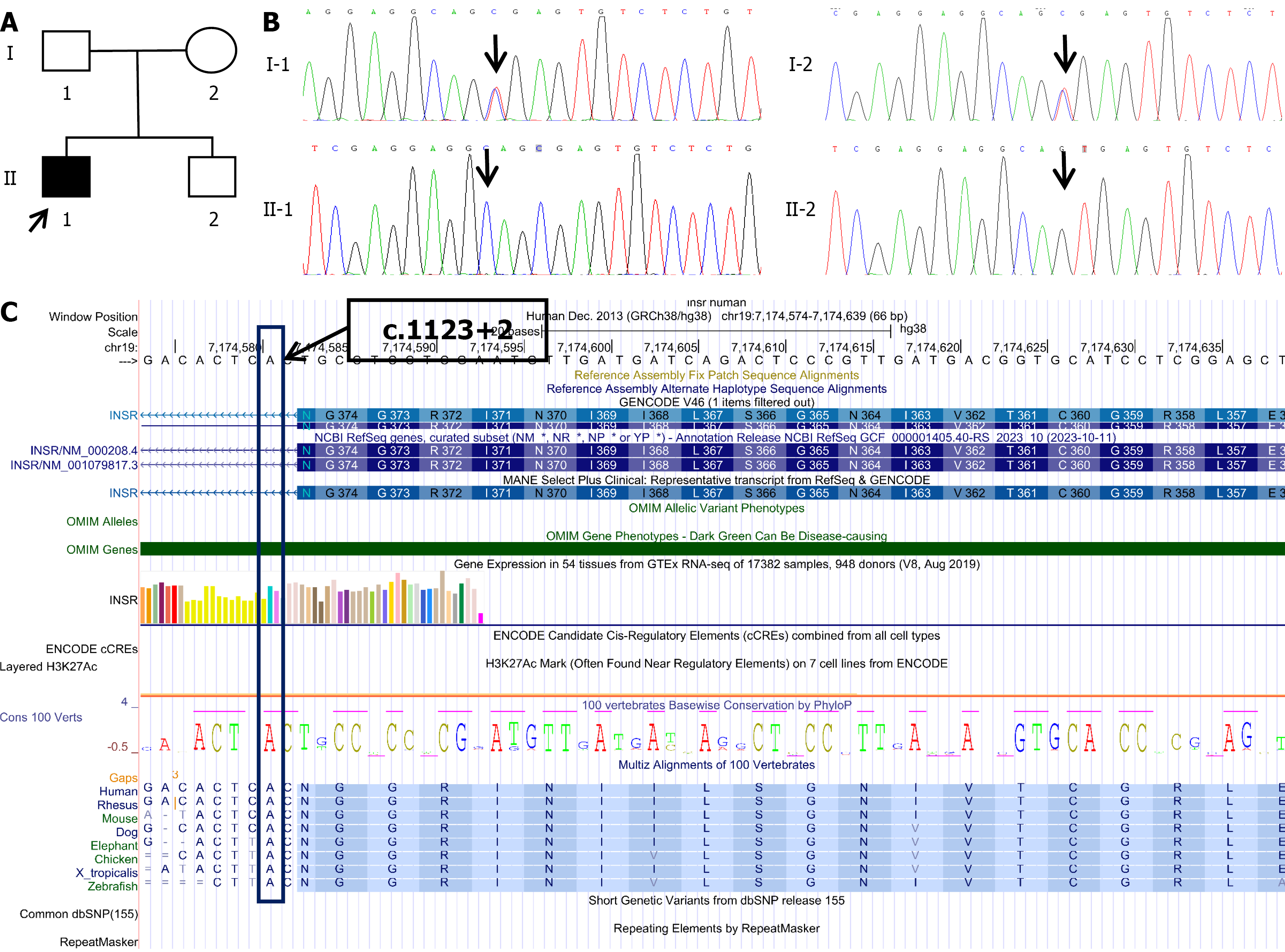

The patient’s recent glycated hemoglobin levels, pancreatic function, and urinalysis results are shown in Table 1. The 24-hour urine protein was 225.4 mg/24 hours. Estimated glomerular filtration rate was 160 mL/minute/1.73 m2. The patient had a homozygous mutation (c.1123+2 T>C) in intron 4 of the INSR gene on chromosome 11. Both parents had heterozygous mutations (c.1123+2 T>C) at this locus, while the patient’s brother was wild-type (c.1123+2 TT; Figure 2).

Abdominal ultrasonography revealed an enlarged spleen and kidneys, and testicular ultrasonography revealed multiple hyperechoic spots in both testes. Cardiac ultrasonography revealed patent foramen ovale and mild tricuspid regurgitation. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain revealed a pineal cyst and adenoid hypertrophy. Pituitary magnetic resonance imaging showed a linear abnormal signal in the lower part of the pituitary gland.

Based on the patient’s medical history, symptoms, signs, laboratory tests, and genetic sequencing results, he was diagnosed with rhabdomyosarcoma and diabetic kidney disease (stage G1A2).

After admission to our department, the patient was treated with a combination of metformin and continuous sub

In 2022, the patient was treated with insulin glargine and insulin to control blood glucose levels. From 2022 to 2024, the patient was treated with insulin glargine (100 units) and insulin aspart 30 units, 30 units, and 30 units before meals to control blood glucose. Starting in 2024, the patient’s plan was changed to metformin, voglibose, sitaglitazone, and empagliflozin to control blood sugar. Currently, the fasting blood sugar level was approximately 6 mmol/L, and the postprandial blood sugar level was 10-20 mmol/L, which was closely related to the patient’s irregular diet.

The results of the follow-up over the past 5 years are shown in Table 1.

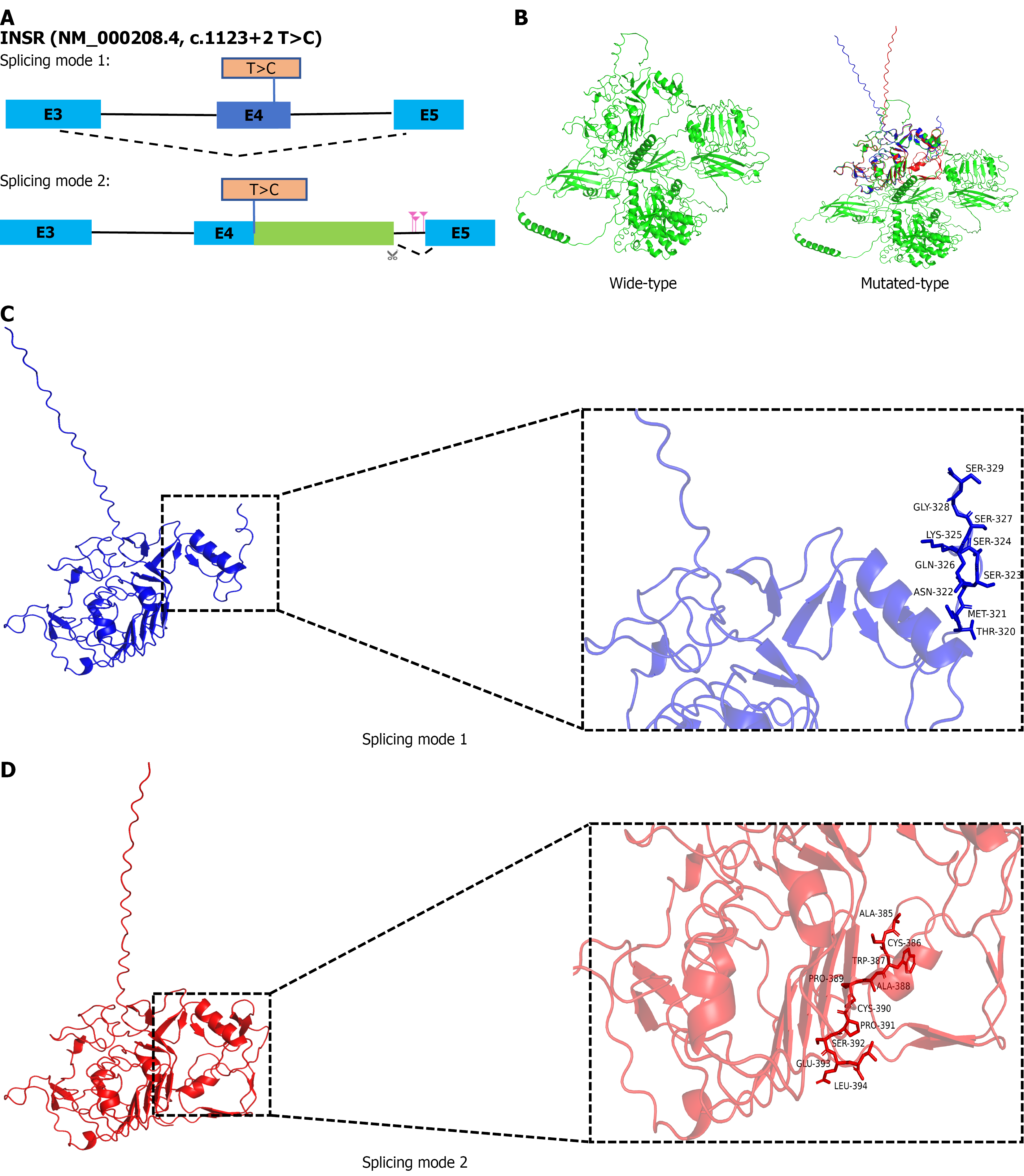

The predicted results of the Rare Disease Data Center RNA splicer (https://rddc.tsinghua-gd.org/)[9,10] indicated that c.1123+2 T>C can generate two splicing modes: (1) Splicing mode 1: Splicing at a new position on the exon of RNA leads to the deletion of the exon sequence; and (2) Splicing mode 2: The original splicing recognition site was disrupted using potential alternative splicing positions in introns, ultimately resulting in the partial inclusion of intron sequences. The possible splicing sites were c.1123+930, c.1123+1038, c.1124-819 (Figure 3A).

Compared to the wild-type protein, the secondary structures of the two splice mutation modes proteins showed significant changes (Table 2): The α-helices, β-sheets, β-turns, and random coils in the two splice mutation modes were significantly reduced. The spatial configuration of the wild-type INSR protein modeled by the Alphafold3 software also exhibited significant abnormalities compared to the predicted spatial configuration after the point mutation (Figure 3B-D). This suggests that c.1123+2 T>C was likely the pathogenic site for this patient, which needs to be verified through subsequent basic experiments.

| Mutation | Total amino acid, n | α-helix | β-fold | β-turn | Random coil |

| Wild-type | 1382 | 299 (21.64) | 249 (18.02) | 52 (3.76) | 782 (56.58) |

| MT1 | 329 | 59 (17.93) | 52 (15.81) | 11 (3.34) | 207 (62.92) |

| MT2 | 394 | 86 (21.83) | 62 (15.74) | 14 (3.55) | 232 (58.88) |

The most notable physical abnormality in this patient was AN, which was first reported and named by Pollitzer in 1890. AN is a keratinizing skin disorder characterized by hyperpigmentation, thickening, and a velvety texture that primarily affects skin folds, such as the neck (99%), armpits (73%), and groin[11]. Several classification methods exist for Curt-classified AN into benign (obesity-related, genetic, and endocrine) and malignant (tumor-associated) types[12]. According to Curt’s classification, our patient had no malignant tumors or related histories, suggesting a benign type. The patient did not present with obesity or other genetic syndromes; therefore, endocrine-type AN was considered. Benign AN is primarily caused by insulin resistance or defects in fibroblast growth factor[11]. Mutations in fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 lead to associated skeletal dysplasia, including Crouzon syndrome with AN[13], lethal type 1 thanatophoric dysplasia[14], severe achondroplasia with developmental delay and ANs[15], achondroplasia[16], and hypochondroplasia[17]. The patient did not have skeletal dysplasia. Combined with multiple laboratory test results indicating hyperinsulinemia, AN was considered to be caused by insulin resistance.

Severe hereditary insulin resistance can be divided into two main categories based on its cause: INSR defects and lipodystrophy[18]. Upon physical examination, no significant lipodystrophy was observed, suggesting that the patient’s insulin resistance was related to INSR defects. Whole-exome sequencing of the patient revealed a splice mutation in intron 4 of the INSR gene, which was validated by Sanger sequencing, further supporting our diagnosis. Diseases caused by insulin resistance due to INSR defects mainly include type A Donohue syndrome, RMS, and type B insulin resistance.

Type A insulin resistance is an autosomal dominant disorder that is rarely reported both domestically and internationally and predominantly observed in adolescent females aged 8-30 years. These individuals do not typically present with obesity or lipoatrophy. The main clinical manifestations include severe insulin resistance, hyperandrogenism, and AN[19]. In some cases, polycystic ovarian syndrome-like features may be present, and some patients may ultimately develop diabetes. However, diabetes is generally mild and patients can survive into adulthood[19]. Only approximately 10% of patients with type A insulin resistance syndrome have mutations in INSR, whereas mutations in other genes, such as those encoding nuclear lamin A, can also cause type A insulin resistance.

Donohue syndrome was first described in 1954 as an autosomal recessive disorder[20]. Its characteristics include severe intrauterine growth retardation, and most affected infants die during infancy. The name is derived from the distinctive elfin features observed at birth, such as short stature, wide-set eyes, low-set ears, thick lips, a flat nose, and other features, including emaciation, paucity of subcutaneous fat, hirsutism, AN, and developmental delay. These individuals also present with impaired glucose regulation and hyperinsulinemia and may exhibit fasting hypoglycemia and postprandial hyperglycemia early on. As the disease progresses, pancreatic β-cell function gradually diminishes, leading to ketoacidosis or death owing to various complications. Donohue syndrome has a very low incidence rate, with over 90% of affected children dying before the age of 2 years, which accounts for the rarity of reports.

RMS is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder primarily caused by compound heterozygous mutations in the INSR gene. It was first reported and named after Rabson-Mendenhall in 1956[2]. Its clinical features include AN, hypertrichosis, growth retardation, reduced subcutaneous fat, dry skin, thickened skin, abnormal facies, bow-shaped lips, premature dentition with incomplete dental development, fissured tongue, thickened nails, joint hyperextension, enlarged external genitalia or precocious puberty, and pineal gland hyperplasia. Some children may present with renal malformations and cardiac abnormalities. All patients exhibited severe hyperinsulinemia with some progression to diabetes, ketoacidosis, or even death. The typical clinical course includes fasting hypoglycemia and postprandial hyperglycemia before the age of 1 years, persistent hyperglycemia between the ages of 3 years and 4 years, and diabetic ketoacidosis, usually during early childhood. Most patients die of intractable diabetic ketoacidosis during adolescence. Lifespan correlates with the residual binding capacity of mutant INSR, with insulin levels declining to undetectable levels over time. Most children survive for 5 years and 15 years. RMS is the only insulin syndrome that is associated with dental abnormalities.

Type B insulin resistance is a disease syndrome centered on severe insulin resistance, primarily caused by the presence of specific anti-INSR antibodies in the circulation[21]. Typical clinical manifestations include severe hyperglycemia or refractory hypoglycemia, AN, hyperandrogenemia, and autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, scleroderma, and overlap syndrome. It is a rare form of diabetes, with fewer than hundred cases reported worldwide, and domestic research is limited to case reports.

The patient presented with significant dental misalignment, pineal gland hyperplasia, and congenital heart anomalies, suggesting a diagnosis of RMS. In RMS, severe insulin resistance is caused by defective INSRs. INSR gene mutations associated with RMS were first reported in 1990[22]. Subsequent reports of INSR gene defects include missense mu

| Mutation type | Amin acid change | Clinical feature | Ref. |

| Missense | Pro193 Leu | Low birth weight, failure to thrive, hypotrichosis, clitoromegaly, and relatively coarse facies | Carrera et al[30] |

| Missense | Ile116Thr/Arg1131Trp | Early extreme hyperinsulinemia that declines over time; severe insulin resistance, growth retardation, acanthosis nigricans, dental anomalies, hyperglycemia and ketoacidosis risk | Longo et al[31] |

| Missense | Pro970Thr/Arg1131Trp | Hyperinsulinemia, growth retardation, acanthosis, dental anomalies, early-onset diabetes | Longo et al[32] |

| Missense | Asn878Ser/Ala1162Val | Severe insulin resistance with marked hyperinsulinemia, acanthosis, growth delay, dysmorphic dentition; refractory hyperglycemia requiring multi-drug and high-dose insulin therapy | Moreira et al[33] |

| Missense | Cys159Phe/Arg229Cys | Extreme insulin resistance, short stature, severe acanthosis, hypertrichosis, dental abnormalities, early-onset hyperglycemia | Thiel et al[34] |

| Missense | Arg209His/Gly359Ser | Markedly reduced receptor, extreme insulin resistance, short stature, severe acanthosis, hypertrichosis, dental anomalies, early diabetes, recurrent infections | Tuthill et al[35] |

| Missense | Arg86Term; Asp261-Leu262 Ins Leu His Val | Severe insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, growth retardation, acanthosis nigricans, dental dysplasia, early-onset diabetes | Müller-Wieland et al[36] |

| Missense/deletion | IVS4-2 A>G/c.2480-2487del | Profound insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, failure to thrive, acanthosis, dental and nail abnormalities, early-life diabetes | Kadowaki et al[37] |

| Missense | Cys279Arg | Child with RMS: Extensive acanthosis nigricans, skin tags, hypertrichosis, short stature, abdominal distension, clitoromegaly, hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia | Duraiswamy et al[38] |

| Missense/deletion | Arg145Cys/19p13.2del 237kbp | Adult RMS misdiagnosed as T1DM: Severe insulin resistance, malnutrition/Low BMI, acanthosis, prognathism, dysmorphic features, diabetic complications (retinopathy) | Almotawa et al[39] |

| Missense/deletion | Pro1131Arg/c.4007_4010delAGAG | Infant with generalized acanthosis, growth retardation, dysmorphism, hypertrichosis, fasting hypoglycemia with hyperinsulinemia | Yan et al[40] |

| Missense | Arg1119Trp/del243Kb(chr19:7150507-7152938) | Severe insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, growth retardation, acanthosis, dental anomalies, early diabetes | Chen et al[41] |

| Missense | Arg141Trp | Marked hyperinsulinemia, acanthosis, growth failure, dental/skin findings, insulin-resistant diabetes requiring complex therapy | Bastaki et al[42] |

There is currently no unified treatment protocol for RMS. Research suggests that the dysfunction of the novel INSR G359S variant is largely due to abnormal receptor processing, rather than mutations inherently impairing signal trans

There has been a case report of a 19-year-old male with RMS who developed diabetic ketoacidosis and required an insulin dosage of up to 500 U/hour (10.6 U/kg/hour). Initially, the patient’s insulin infusion was mixed with U-100 regular insulin. However, to minimize the volume, the product was combined with U-500 insulin. Diabetic ketoacidosis was eventually managed at infusion rates of 400-500 U/hour[29]. However, our case did not present such extreme dose requirements in 2019. Possible reasons include: (1) The c.1123+2 T>C variant may have a weaker impact on INSR function or mainly affects receptor processing without completely losing signaling; and (2) The younger age at onset and shorter disease duration may allow pancreatic β-cells to maintain compensatory function. Our follow-up indicated that, as the disease progressed, pancreatic function gradually declined, insulin usage increased annually, and blood glucose control worsened, consistent with the aforementioned speculation.

This case highlights the importance of early molecular diagnosis and family screening in patients with RMS to characterize mutations and inform prognostic assessments. Concurrently, long-term monitoring of pancreatic function and treatment intensity is crucial, with careful attention to the risk of progression requiring high-dose insulin or the development of diabetic ketoacidosis. In terms of functional studies, further in vitro expression/processing and signaling pathway assessments of rare variants, such as c.1123+2 T>C, should be conducted to clarify their pathogenic mechanisms and provide a basis for individualized treatment (such as leptin replacement or other targeted strategies).

The current evidence (in line with American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics guidelines) is based on computational predictions and co-segregation within the pedigree (parents as carriers, brother as wild-type), but lacks direct functional evidence, such as in vitro splicing assays, to definitively confirm that this mutation causes aberrant splicing. This case highlights the importance of early genetic diagnosis in rare metabolic disorders, such as RMS, particularly in identifying novel mutations that impair receptor function. Long-term management remains challenging as the pancreatic function deteriorates. Continued monitoring of patients with RMS is crucial for adapting treatment strategies to prevent complications, such as diabetic ketoacidosis.

| 1. | Ando A. [Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome]. Nihon Rinsho. 1994;52:2641-2642. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Rabson SM, Mendenhall EN. Familial hypertrophy of pineal body, hyperplasia of adrenal cortex and diabetes mellitus; report of 3 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1956;26:283-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gong W, Chen W, Dong J, Liao L. Rabson-Mendenhall Syndrome: Analysis of the Clinical Characteristics and Gene Mutations in 42 Patients. J Endocr Soc. 2024;8:bvae123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Aftab S, Shaheen T, Asif R, Anjum MN, Saeed A, Manzoor J, Cheema HA. Management challenges of Rabson Mendenhall syndrome in a resource limited country: a case report. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2022;35:1429-1432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Al-Kandari H, Al-Abdulrazzaq D, Al-Jaser F, Al-Mulla F, Davidsson L. Rabson-Mendenhall Syndrome in a brother-sister pair in Kuwait: Diagnosis and 5 year follow up. Prim Care Diabetes. 2021;15:175-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ben Abdelaziz R, Ben Chehida A, Azzouz H, Boudabbous H, Lascols O, Ben Turkia H, Tebib N. A novel homozygous missense mutation in the insulin receptor gene results in an atypical presentation of Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome. Eur J Med Genet. 2016;59:16-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gosavi S, Sangamesh S, Ananda Rao A, Patel S, Hodigere VC. Insulin, Insulin Everywhere: A Rare Case Report of Rabson-Mendenhall Syndrome. Cureus. 2021;13:e13126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rojas Velazquez MN, Blanco F, Ayala-Lugo A, Franco L, Jolly V, Di Tore D, Martínez de Lapiscina I, Janner M, Flück CE, Pandey AV. A Novel Mutation in the INSR Gene Causes Severe Insulin Resistance and Rabson-Mendenhall Syndrome in a Paraguayan Patient. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:3143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Shi X, Liu X, Zong Y, Zhao Z, Sun Y. Novel compound heterozygous variants in MARVELD2 causing autosomal recessive hearing loss in two Chinese families. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2024;12:e2502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhang Y, Bi S, Dai L, Zhao Y, Liu Y, Shi Z. Clinical report and genetic analysis of a Chinese neonate with craniofacial microsomia caused by a splicing variant of the splicing factor 3b subunit 2 gene. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2023;11:e2268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Torley D, Bellus GA, Munro CS. Genes, growth factors and acanthosis nigricans. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:1096-1101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wojas-Pelc A, Wielowieyska-Szybińska D, Lipko-Godlewska S. [Clinical types of acanthosis nigricans]. Przegl Lek. 2002;59:537-539. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Meyers GA, Orlow SJ, Munro IR, Przylepa KA, Jabs EW. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) transmembrane mutation in Crouzon syndrome with acanthosis nigricans. Nat Genet. 1995;11:462-464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in RCA: 271] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Baker KM, Olson DS, Harding CO, Pauli RM. Long-term survival in typical thanatophoric dysplasia type 1. Am J Med Genet. 1997;70:427-436. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Tavormina PL, Bellus GA, Webster MK, Bamshad MJ, Fraley AE, McIntosh I, Szabo J, Jiang W, Jabs EW, Wilcox WR, Wasmuth JJ, Donoghue DJ, Thompson LM, Francomano CA. A novel skeletal dysplasia with developmental delay and acanthosis nigricans is caused by a Lys650Met mutation in the fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 gene. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:722-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Van Esch H, Fryns JE. Acanthosis nigricans in a boy with achondroplasia due to the classical Gly380Arg mutation in FGFR3. Genet Couns. 2004;15:375-377. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Leroy JG, Nuytinck L, Lambert J, Naeyaert JM, Mortier GR. Acanthosis nigricans in a child with mild osteochondrodysplasia and K650Q mutation in the FGFR3 gene. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A:3144-3149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Melvin A, O'Rahilly S, Savage DB. Genetic syndromes of severe insulin resistance. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2018;50:60-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jin J, Liang X, Wei J, Xu L. A New Mutation of the INSR Gene in a 13-Year-Old Girl with Severe Insulin Resistance Syndrome in China. Biomed Res Int. 2021;2021:8878149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Morooka K. [Leprechaunism (Donohue's syndrome)]. Ryoikibetsu Shokogun Shirizu. 1995;262-264. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Zhao L, Li W, Liu L, Duan L, Wang L, Yang H, Zhang H, Li Y. Clinical Features and Outcome Analysis of Type B Insulin Resistance Syndrome: A Single-Center Study in China. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;109:e175-e181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Davis A, Yarasheski KE, White NH, Canter C, Marshall BA. Defective insulin receptors in Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome cause complete peripheral insulin resistance but minimal hepatic insulin response remains. Pediatr Diabetes. 2000;1:66-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kim D, Cho SY, Yeau SH, Park SW, Sohn YB, Kwon MJ, Kim JY, Ki CS, Jin DK. Two novel insulin receptor gene mutations in a patient with Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome: the first Korean case confirmed by biochemical, and molecular evidence. J Korean Med Sci. 2012;27:565-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kusari J, Takata Y, Hatada E, Freidenberg G, Kolterman O, Olefsky JM. Insulin resistance and diabetes due to different mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain of both insulin receptor gene alleles. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:5260-5267. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Landrum MJ, Lee JM, Riley GR, Jang W, Rubinstein WS, Church DM, Maglott DR. ClinVar: public archive of relationships among sequence variation and human phenotype. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D980-D985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1734] [Cited by in RCA: 2550] [Article Influence: 196.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Karczewski KJ, Francioli LC, Tiao G, Cummings BB, Alföldi J, Wang Q, Collins RL, Laricchia KM, Ganna A, Birnbaum DP, Gauthier LD, Brand H, Solomonson M, Watts NA, Rhodes D, Singer-Berk M, England EM, Seaby EG, Kosmicki JA, Walters RK, Tashman K, Farjoun Y, Banks E, Poterba T, Wang A, Seed C, Whiffin N, Chong JX, Samocha KE, Pierce-Hoffman E, Zappala Z, O'Donnell-Luria AH, Minikel EV, Weisburd B, Lek M, Ware JS, Vittal C, Armean IM, Bergelson L, Cibulskis K, Connolly KM, Covarrubias M, Donnelly S, Ferriera S, Gabriel S, Gentry J, Gupta N, Jeandet T, Kaplan D, Llanwarne C, Munshi R, Novod S, Petrillo N, Roazen D, Ruano-Rubio V, Saltzman A, Schleicher M, Soto J, Tibbetts K, Tolonen C, Wade G, Talkowski ME; Genome Aggregation Database Consortium, Neale BM, Daly MJ, MacArthur DG. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature. 2020;581:434-443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7255] [Cited by in RCA: 6996] [Article Influence: 1166.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Stenson PD, Mort M, Ball EV, Chapman M, Evans K, Azevedo L, Hayden M, Heywood S, Millar DS, Phillips AD, Cooper DN. The Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD(®)): optimizing its use in a clinical diagnostic or research setting. Hum Genet. 2020;139:1197-1207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 529] [Article Influence: 88.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Okawa MC, Cochran E, Lightbourne M, Brown RJ. Long-Term Effects of Metreleptin in Rabson-Mendenhall Syndrome on Glycemia, Growth, and Kidney Function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107:e1032-e1046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Moore MM, Bailey AM, Flannery AH, Baum RA. Treatment of Diabetic Ketoacidosis With Intravenous U-500 Insulin in a Patient With Rabson-Mendenhall Syndrome: A Case Report. J Pharm Pract. 2017;30:468-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Carrera P, Cordera R, Ferrari M, Cremonesi L, Taramelli R, Andraghetti G, Carducci C, Dozio N, Pozza G, Taylor SI. Substitution of Leu for Pro-193 in the insulin receptor in a patient with a genetic form of severe insulin resistance. Hum Mol Genet. 1993;2:1437-1441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Longo N, Wang Y, Pasquali M. Progressive decline in insulin levels in Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:2623-2629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Longo N, Wang Y, Smith SA, Langley SD, DiMeglio LA, Giannella-Neto D. Genotype-phenotype correlation in inherited severe insulin resistance. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:1465-1475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Moreira RO, Zagury RL, Nascimento TS, Zagury L. Multidrug therapy in a patient with Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome. Diabetologia. 2010;53:2454-2455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Thiel CT, Knebel B, Knerr I, Sticht H, Müller-Wieland D, Zenker M, Reis A, Dörr HG, Rauch A. Two novel mutations in the insulin binding subunit of the insulin receptor gene without insulin binding impairment in a patient with Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome. Mol Genet Metab. 2008;94:356-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Tuthill A, Semple RK, Day R, Soos MA, Sweeney E, Seymour PJ, Didi M, O'rahilly S. Functional characterization of a novel insulin receptor mutation contributing to Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2007;66:21-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Müller-Wieland D, van der Vorm ER, Streicher R, Krone W, Seemanova E, Dreyer M, Rüdiger HW, Rosipal SR, Maassen JA. An in-frame insertion in exon 3 and a nonsense mutation in exon 2 of the insulin receptor gene associated with severe insulin resistance in a patient with Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome. Diabetologia. 1993;36:1168-1174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Kadowaki H, Takahashi Y, Ando A, Momomura K, Kaburagi Y, Quin JD, MacCuish AC, Koda N, Fukushima Y, Taylor SI, Akanuma Y, Yazaki Y, Kadowaki T. Four mutant alleles of the insulin receptor gene associated with genetic syndromes of extreme insulin resistance. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;237:516-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Duraiswamy A, Aithal SS, Aithal S, Nandakumar A. Beyond the Obvious: Acanthosis Nigricans as a Clue to the Rare Case of Rabson-Mendenhall Syndrome. Indian J Paediatr Dermatol. 2024;25:246-249. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 39. | Almotawa F, Mushiba AM, Alqahtani N, Mashi A. Rabson-Mendenhall Syndrome Nearly Misdiagnosed as Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: A Case Report. Cureus. 2025;17:e81190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Yan S, Sheng Y, Hui HZ, Zhou CY, Liu DM. Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome presented as severe acanthosis nigricans in an infant harboring novel mutations in the INSR gene: a case report. Front Pediatr. 2025;13:1511429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Chen X, Wang H, Wu B, Dong X, Liu B, Chen H, Lu Y, Zhou W, Yang L. One Novel 2.43Kb Deletion and One Single Nucleotide Mutation of the INSR Gene in a Chinese Neonate with Rabson-Mendenhall Syndrome. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2018;10:183-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Bastaki F, Nair P, Mohamed M, Khadora MM, Saif F, Tawfiq N, Al-Ali MT, Hamzeh AR. Identification of a Novel Homozygous INSR Variant in a Patient with Rabson-Mendenhall Syndrome from the United Arab Emirates. Horm Res Paediatr. 2017;87:64-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/