Published online Jan 15, 2026. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v17.i1.110502

Revised: July 6, 2025

Accepted: November 18, 2025

Published online: January 15, 2026

Processing time: 220 Days and 18.9 Hours

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) represents a significant challenge for diabetes management and public health as it affects the quality of life and metabolic control of millions of people around the world. Characterized by persistent al

Core Tip: Diabetic kidney disease is a major complication of diabetes and a leading cause of chronic kidney disease. Traditional markers such as albuminuria and estimated glomerular filtration rate often detect damage at a late stage, limiting early intervention. Emerging urinary biomarkers including kidney injury molecule 1, neutrophil gelatinase associated lipocalin, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, and urinary microRNAs offer earlier and more specific detection of tubular injury, inflammation, and oxidative stress. These biomarkers enhance risk assessment, disease monitoring, and evaluation of treatment response. Incorporating them into clinical practice could enable earlier diagnosis, personalized therapy, and improved outcomes in diabetic kidney disease management.

- Citation: Gembillo G, Soraci L, Messina R, Lo Cicero L, Spadaro G, Cuzzola F, Calderone M, Ricca MF, Di Piazza S, Sudano F, Peritore L, Santoro D. Urinary biomarkers of diabetic kidney disease. World J Diabetes 2026; 17(1): 110502

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v17/i1/110502.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v17.i1.110502

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) constitutes one of the most significant microvascular complications of diabetes mellitus and remains the leading cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) globally. Epidemiological data indicate that up to 30%-40% of individuals with diabetes will develop DKD during the course of their disease, imposing a substantial burden on healthcare systems worldwide[1]. Despite considerable advancements in glycemic control and renoprotective therapies, the morbidity and mortality associated with DKD continue to escalate, underscoring the imperative need for improved diagnostic and prognostic tools. The current diagnostic framework for DKD predominantly relies upon the assessment of albuminuria and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), as endorsed by the KDIGO 2022 Clinical Practice Guideline for Diabetes Management in CKD. Elevated urinary albumin excretion, typically quantified via the urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (uACR), is widely recognized as a marker of glomerular injury and an independent predictor of progressive renal impairment and cardiovascular events. Nonetheless, both albuminuria and eGFR possess inherent limitations. Albuminuria may exhibit substantial biological variability and can be influenced by non-renal factors such as exercise, infection, and hemodynamic changes, thereby reducing its specificity. Furthermore, a considerable proportion of individuals with diabetes exhibit progressive renal decline in the absence of significant albuminuria, a phenotype now recognized as non-albuminuric DKD (NADKD). NADKD may be especially prevalent in patients with type 2 diabetes, and these individuals tend to be older, more often female, and may progress more slowly to ESKD while still being at increased cardiovascular risk. Furthermore, albuminuria may appear only after substantial structural damage has already occurred, making it a relatively late indicator of disease onset. Emerging evidence suggests that albuminuria reflects primarily glomerular injury, while early tubular and interstitial damage, crucial in DKD pathogenesis, may remain undetected. This discrepancy underscores the need to supplement albuminuria with novel urinary biomarkers that can detect earlier, subtler renal injury and provide more comprehensive risk stratification. These biomarkers, reflecting distinct pathogenic processes including tubular injury, interstitial inflammation, oxidative stress, and fibrogenesis, offer the potential to provide a more sensitive and specific means of detecting early kidney damage, monitoring disease progression, and evaluating therapeutic response in DKD. Urinary biomarkers such as kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1), neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), and urinary microRNA (miRNA) have been investigated extensively and demonstrate promising associations with histopathological alterations and clinical outcomes that often precede overt microalbuminuria.

This review aims to provide a comprehensive synthesis of current evidence regarding urinary biomarkers in DKD, emphasizing their biological underpinnings, clinical applicability, and the challenges that impede their integration into routine clinical practice. Advancing biomarker-guided strategies holds the promise of facilitating earlier diagnosis, more precise risk stratification, and personalized therapeutic interventions, ultimately improving outcomes for patients with DKD. This review also aims to provide a comprehensive synthesis of current evidence regarding urinary biomarkers in DKD, emphasizing their biological underpinnings, clinical applicability, and the challenges that impede their integration into routine clinical practice. Advancing biomarker-guided strategies holds the promise of facilitating earlier diagnosis, more precise risk stratification, and personalized therapeutic interventions, ultimately improving outcomes for patients with DKD.

DKD is a common microvascular complication in both type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), alongside diabetic retinopathy and peripheral neuropathy. The pathophysiology is complex and multifactorial, driven by an interplay between genetic susceptibility, environmental influences, and systemic metabolic derangements.

The primary pathogenic trigger is chronic hyperglycemia, which arises from absolute insulin deficiency in T1DM or insulin resistance in T2DM, disrupting normal glucose homeostasis. Sustained high glucose levels set in motion a cascade of pathogenic processes, such as oxidative stress, inflammation, and the activation of pro-fibrotic signalling pathways, which progressively damage renal structures, leading to glomerular sclerosis, tubulointerstitial fibrosis, and ultimately to a decline in kidney function.

Adipose tissue dysfunction further contributes by releasing excess free fatty acids and proinflammatory cytokines, that exacerbate insulin resistance and promote systemic inflammation[2]. Moreover, there is growing evidence that gut dysbiosis is involved in the development of insulin resistance, emphasising the important role of the intestinal microbiota in maintaining metabolic balance[3].

Mitochondrial glucose metabolism, whether under aerobic or anaerobic conditions, inevitably generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) as by-products with a marked imbalance between pro-oxidant and antioxidant systems[4]. This oxidative stress plays a central role in diabetic complications, including DKD, by inducing cellular injury in renal tissue[5].

Several molecular pathways have been identified in the progression of DKD. One key mechanism involves the accumulation of advanced glycation end-products, which primarily interact with their receptor and trigger a cascade of downstream signalling events that promote inflammation, oxidative stress, and structural alterations[6].

Another critical pathway is protein kinase C (PKC), particularly the PKC-α isoform, which is activated in hy

The hexosamine biosynthetic pathway also contributes to diabetic complications, leading to the generation of pro-inflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, transforming growth factor-β, and intercellular adhesion molecule-1, which contribute to vascular and glomerular injury. Although this metabolic pathway was originally studied in the context of diabetic retinopathy, its effects also extend to the kidney and other tissues[8].

In addition, the polyol pathway becomes increasingly active under hyperglycemic conditions, with aldose reductase catalysing the reduction of glucose to sorbitol[9], impairing the cell’s antioxidant defences and exacerbating oxidative stress. Aldose reductase, its downstream effects, and the aforementioned pathogenic mechanisms are all associated with the development and progression of various diabetic complications, which often coexist with DKD or exacerbate its severity[10].

Histologically, early DKD is characterized by thickening of the glomerular basement membrane and loss of endothelial cell fenestrations, changes that are primarily due to oxidative stress and inflammatory insults. These initial alterations precede glomerular hypertrophy and are accompanied by a state of hyperfiltration[11] mediated in part by activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) and its induced vasoconstriction, and further contributes to glomerular injury, inflammation, and fibrosis[12]. Over time, these early structural and molecular changes progress to more severe pathological features, including diffuse mesangial sclerosis, nodular glomerulosclerosis, glomerular microaneurysms, and intimal fibrosis[13].

An emerging concept in the progression of DKD is metabolic memory, which refers to persistent cellular and tissue dysfunction, even after normoglycemia is achieved. This concept highlights the importance of early intervention and may involve epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation and histone acetylation, as well as long-lasting inflammatory and oxidative signals[14].

The treatment of DKD remains particularly challenging due to its multifactorial and progressive pathophysiology, which involves a complex interplay of metabolic, hemodynamic, inflammatory, and fibrotic mechanisms[15]. This complexity necessitates a multifaceted therapeutic approach, yet the heterogeneity in disease progression and individual patient response further complicates effective long-term management[16,17]. The main metabolic, hemodynamic, and inflammatory pathways contributing to DKD are summarized in Figure 1.

In this context, the identification of reliable and specific biomarkers for DKD is crucial, as they could enable earlier diagnosis, better risk stratification, and more personalized therapeutic strategies, ultimately improving clinical outcomes and slowing disease progression.

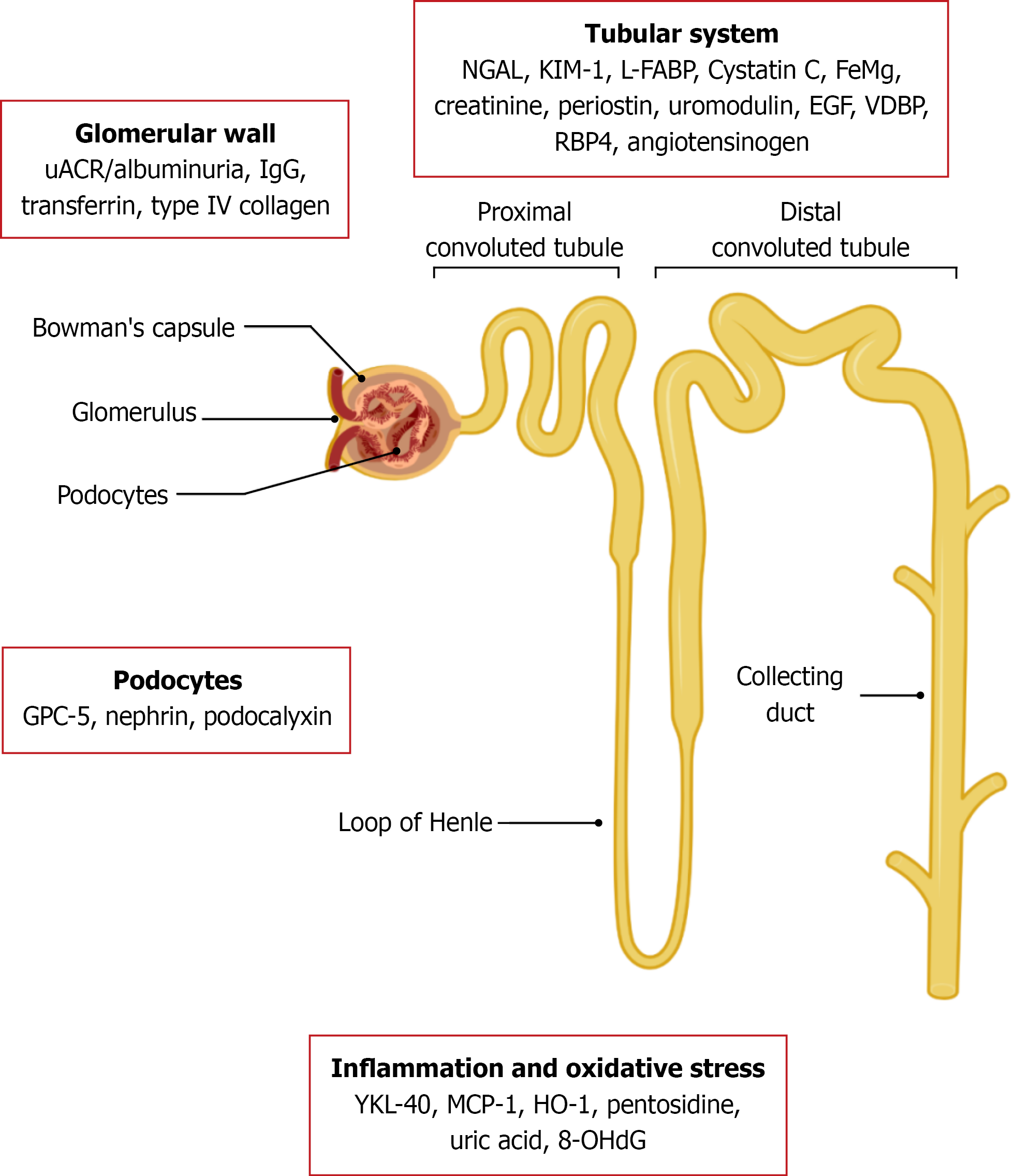

Urinary biomarkers play a pivotal role in understanding the pathogenesis of DKD and offer promising tools for early diagnosis, monitoring progression, and guiding therapeutic interventions. These biomarkers can be categorized based on the renal compartment or pathological process they primarily reflect, such as glomerular damage, tubular injury, inflammation, oxidative stress, or fibrosis (Table 1)[18-30].

| Biomarker | Source | Diagnostic accuracy | Clinical significance and validation status | Prospective | Contras and limitations |

| uACR/albuminuria | Glomerular capillary wall | AUC: 0.522[18]-0.933[19]; sensitivity 77% and specificity 92% for microabuminuria; sensitivity 88% and specificity 90% for macroalbuminuria[20] | Standard early marker for DKD; persistent elevation indicates nephropathy | Widely used; inexpensive, reproducible | Affected by blood pressure, exercise, and infections (risk of false positives). DKD may be normoalbuminuric normal uACR and albuminuria do not always exclude DKD |

| GPC-5 | Podocyte injury | ROC curve of urinary GPC-5/creatinine ratio comparing T2DM without nephropathy and those with nephropathy reveals a sensitivity of 93.3% and a specificity of 80%[21] | Emerging marker of podocyte damage; may reflect early glomerular dysfunction in DKD; more studies needed to validate it as a diagnostic tool of incipient nephropathy | Potential early marker of podocyte injury; non-invasive detection in urine | Limited validation (small sample size studies); clinical utility and standardization not yet established |

| Transferrin | Large protein leakage from the glomerular wall | AUC: 0.846 (95%CI: 0.810-0.882); sensitivity 69.8%, specificity 90.1% (for a cut-off value of 1.15)[22] | Suggests early glomerular barrier compromise before albuminuria. Since significant transferrin levels have been found in normoalbuminuric T2DM patients, it could be suitable as a marker of early-stage DKD; nevertheless, very limited body of research | Earlier than macroalbuminuria; non-invasive | Limited specificity (false positives in primary glomerulonephritis and hypertension in nondiabetic populations; elevated in other proteinuric states) |

| Immunoglobulins (IgG and IgM) | Large protein leakage from the glomerular wall | AUC: 0.894 (95%CI: 0.848-0.930); sensitivity 75.53%, specificity 92.31% (for a cut-off value of 8.56)[23] | Indicates severe dysfunction. Limited body of evidence in T2DM | Indicative of more advanced damage; could be used in combination with transferrin to enhance diagnostic values | May be negative until late stages of disease (due to high molecular weight of IgG). Testing is more invasive on the one hand, and insufficiently standardized on the other |

| Nephrin | Podocyte injury | Not available for DKD | Promising marker for detection of early glomerular injury in multiple studies[24] | Specific to podocyte injury; early detection possible | It does not predict early renal dysfunction in DKD[40]. Requires specialized assays, limited availability |

| Type IV collagen | Matrix remodeling at the glomerular basement membrane | AUC not consistently reported; significantly elevated in early DKD[25]. More sensitive than microalbuminuria but exact percentages not uniformly available | Associated with structural glomerular damage and fibrosis. Validated in large multicentric cohort across DKD stages. Some promising data, but more investigation on larger scale is needed | Reflects chronic structural damage, therefore useful to detect fibrosis | Limited validation (small-to-moderate sample size studies; lack of ROC quantification and cut-offs)[26,30]. Limited utility in early DKD, overlaps with other markers |

| Podocalyxin | Podocyte injury | AUC: 0.86 (95%CI: 0.81-0.91) alone; combined with α2-MG: AUC: 0.88 (95%CI: 0.83-0.93)[27], in another small study, AUC: 0.996[29]. Sensitivity 73.3%, specificity 93.3% at cut-off 43.8 ng/mL[28] | Linked to detachment and loss of podocytes. Validated in cross-sectional and prospective cohorts of 42-200 patients[27]. Might be a highly accurate biomarker of early podocyte injury, but more studies on larger scale are needed | Sensitive for podocyte detachment, useful in active disease | Not widely validated (limited sample size studies)[27,29]; inter-assay variability; requires advanced laboratory methods |

Glomerular biomarkers provide valuable insights into early and progressive damage to the glomerular filtration barrier in DKD. As outlined in Table 1, these markers reflect distinct aspects of glomerular injury, including permeability changes (e.g., albuminuria), podocyte damage (e.g., nephrin, podocalyxin), and structural remodeling (e.g., type IV collagen). High-molecular-weight proteins like transferrin and immunoglobulins G (IgG), typically restricted by an intact glomerular barrier, appear in urine only when that barrier is compromised, indicating more advanced damage. Additionally, markers like ceruloplasmin signal oxidative stress and inflammation within the glomerulus. Collectively, these biomarkers enhance diagnostic and prognostic accuracy beyond albuminuria alone.

UACR: The uACR, is a key indicator of kidney damage, particularly in DKD. A higher ACR, specifically above 30 mg/g, can be an early sign of kidney disease, even with normal eGFR. uACR is commonly used to stratify the risk for progression of CKD and DKD, morbidity and mortality. Schultes et al[31] studied the impact of uACR point-of-care testing (POCT) on the diagnosis and management of DKD. Their study showed that DKD was suspected at visit in 9.9% of the participants based on the actual ACR POCT values, thus ACR POCT increased the detection rate of DKD in patients with diabetes. In 18.5% of the entire study population, ACR POCT led to a change of medication. ACR POCT showed, in this research, a considerable impact on the diagnosis and treatment of DKD.

The diagnosis of DKD is based on some clinical findings, such as albuminuria, which is defined as ACR > 30 mg/g or urinary albumin of 30-300 mg/day. It is classified as the first DKD indicator, a biomarker for the progression of this disease and a cause of GFR reduction. Albumin is a small negatively charged protein synthesized by the liver and it is poorly filtered by glomeruli due to electrostatic repulsion; in fact, in healthy patients, levels of albuminuria should be under 30 mg in a 24-hour urine sample. Albumin urinary excretion is controlled by several hormones, including glucocorticoids and insulin, that are impaired in conditions like diabetes, this dysregulation leads to abnormal albumin metabolism. When the integrity of the glomerular filtration barrier is altered, there are increased levels of albuminuria due to the major pore size and the impaired electrical homeostasis of glomerular basement membrane. It is known that albuminuria is also linked to the megalin and cubilin encoding gene (CUBN): Reduced megalin expression is associated with lower capacity of the kidney tubular epithelial cells to reabsorb albumin filtered by glomeruli[32] and CUBN is involved in the development of albuminuria in European and African populations[33]. Albuminuria is categorized into three levels: A1 < 30 mg/24 hours or < 30 mg/g (normal or mildly increased); A2 30-300 mg/24 hours or 30-300 mg/g (moderately increased); A3 > 300 mg/24 hours or > 300 mg/g (severely increased)[34]. It will gradually worsen and turn into clinically severe albuminuria grade A3 at 10-15 years after diabetes diagnosis. The prevalence of this biomarker is different between patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes: In T2DM albuminuria A3 ranges from 5% to 48% and A2 occurs in 20% of cases; In T1DM A3 ranges from 8% to 22% and A2 will be found in 13% of cases[34]. The presence of albuminuria A2 in a diabetic patient must be confirmed by two measurements to achieve the diagnosis of DKD, although a significant number of patients with diabetes may present prevailing interstitial damage with no glomerular lesion. Thus, renal function could be impaired without the development of albuminuria. These patients are known as non-albuminuric, affected by NADKD. Their phenotype is characterized by decreased eGFR and albuminuria < 30 mg/24 hours and ACR < 17-30 mg/g. It is possible that this pathological pathway is different from the typical presentation[35]. NADKD has spread among the diabetic population, found in approximately 20%-40% of DKD cases and it presents with a non-typical phenotype: Patients with NADKD tend to have a slower eGFR decline than albuminuric patients and diabetic patients without DKD. They also have a lower risk of progression to ESKD, they are older, often women, with shorter duration of diabetes, lower glycosylated hemoglobin levels and blood pressure[35]. Although there are differences between NADKD and ADKD, a subset of patients might also progress gradually to the end stage without albuminuria. It is fundamental to underline that the occurrence of albuminuria is strictly linked to a major cardiovascular risk. In addition to a reduced eGFR, it increases mortality from all causes, such as endocrinological, metabolic and cardiovascular[36]. Therefore, it is recommended that albuminuric patients are treated promptly with diet, lower blood levels, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors, nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, or glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, in order to reduce the glomerular damage and slow the progression of DKD and cardiovascular complications[37]. Albuminuria is linked to an increased risk of developing subclinical atherosclerosis[38] both as a diabetes complication and as an independent risk factor itself. It is also associated with myocardial infarction and heart failure with systolic dysfunction; in fact, it is also correlated with renal and cardiac fibrosis[39].

Glypican-5: Glypican-5 (GPC-5), a podocyte surface heparan sulfate proteoglycan, has emerged as a significant glomerular biomarker in DKD. Elevated urinary GPC-5 levels have been observed in patients with T2DM, particularly those exhibiting early-stage kidney damage. Studies have demonstrated a strong correlation between urinary GPC-5 concentrations and common markers of renal injury, such as albuminuria and eGFR. El-Kafrawy et al[21] demonstrated that urinary GPC-5 concentrations were significantly higher in diabetic patients with renal involvement compared to those without DKD and healthy controls. Furthermore, a 52-week follow-up study indicated that increased urinary GPC-5 levels were associated with a decline in eGFR and an increase in albuminuria, suggesting its potential as an early indicator of renal dysfunction in DKD.

Transferrin: Urinary transferrin has emerged as a promising biomarker for early detection and monitoring of DKD. As a low-molecular-weight glycoprotein (76.5 kDa), transferrin is more readily filtered through the glomerular barrier compared to albumin, making its urinary excretion a sensitive indicator of glomerular injury. Elevated urinary transferrin levels have been observed in diabetic patients, even in the absence of albuminuria. In fact, a recent meta-analysis by Li et al[40] demonstrated that urinary transferrin has a high combined sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing early DKD. Furthermore, longitudinal studies have shown that increased urinary transferrin excretion predicts the development of microalbuminuria in normoalbuminuric diabetic patients. For instance, a study[41] reported that urinary transferrin levels correlated with the progression of biopsy-proven glomerular diffuse lesions and interstitial fibrosis, suggesting its role in monitoring disease progression. Additionally, another study found that urinary transferrin excretion increased significantly with the severity of glomerular lesions in diabetic patients, further supporting its utility as an early biomarker of DKD[42]. These findings underscore the potential of urinary transferrin as a non-invasive biomarker for the early detection and monitoring of DKD, offering a valuable tool for clinicians in managing patients with diabetes at risk of renal complications.

Immunoglobulins: Urinary IgG and immunoglobulin M (IgM) have emerged as significant biomarkers in the early detection and progression monitoring of DKD. Urinary IgG excretion is notably higher in diabetic patients compared to healthy controls, even before the onset of microalbuminuria. This elevation correlates with the progression of glomerular diffuse lesions and can predict the development of microalbuminuria in normoalbuminuric diabetic patients. Furthermore, urinary IgG levels have been associated with the severity of glomerular damage[43]. IgM, being the largest antibody, also appears in urine in diabetic patients, reflecting significant glomerular injury. Increased urinary IgM excretion has been linked to a higher risk of renal failure and is considered an early predictor of DKD progression, independent of albuminuria levels. Notably, urinary IgM excretion is inversely associated with renal survival in diabetic patients, suggesting its potential as a prognostic marker[44]. Importantly, not only total IgG but also its subtypes, such as IgG2 and IgG4, have shown relevance. Gohda et al[45] reported that an elevated IgG2/IgG4 ratio in urine is indicative of altered glomerular size and charge selectivity, which are early indicators of DKD. Another study, further demonstrated that a urinary IgG threshold above 2.45 mg/L was predictive of DKD onset and progression, reinforcing its utility in clinical risk stratification[46]. In support of these findings, Narita et al[47] demonstrated that increased urinary excretions of IgG, along with ceruloplasmin and transferrin, significantly predicted the development of microalbuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetes, suggesting a role for these proteins as early markers of glomerular injury, even before classic albuminuria appears. This predictive value was further reinforced by an earlier study[48], which showed a parallel increase in urinary IgG and other plasma proteins in normoalbuminuric diabetic patients, indicating early glomerular permeability changes independent of albumin excretion. Notably, these abnormalities appear to be reversible with improved glycemic control, as shown by Narita et al[49], who reported that tighter glucose regulation significantly reduced urinary IgG and ceruloplasmin excretion. These studies collectively emphasize that urinary IgG not only reflects existing renal damage but also serves as a dynamic biomarker responsive to therapeutic interventions, underscoring its prognostic and potentially diagnostic utility in early DKD.

Nephrin: Nephrin is a transmembrane protein expressed in glomerular podocytes (180 kDa) and plays a crucial role in maintaining the structural integrity of the glomerular filtration barrier. Its urinary excretion, termed “nephrinuria”, has emerged as an early and sensitive indicator of podocyte injury and is increasingly recognized as a potential biomarker for DKD. Elevated nephrin levels have been detected in the urine of patients across a range of glomerular pathologies, including DKD, lupus nephritis, and preeclampsia, supporting its utility in diverse clinical contexts[50]. Notably, ne

To date, the best validated non-invasive biomarker to detect the onset of diabetes mellitus (DM) is microalbuminuria, but recently it has been shown that many predictive markers are able to detect the presence of the disease even before albuminuria. In addition to the glomerular involvement, there is also a tubular component in the renal complications of diabetes, as demonstrated by the detection of renal tubular proteins and enzymes in the urine. The tubular involvement may precede the glomerular involvement, as these tubular products are already detectable before microalbuminuria[56]. A summary of urinary tubular biomarkers important in the diagnosis of DKD is reported Table 2[57-70].

| Biomarker | Source | Diagnostic accuracy | Clinical significance | Validation status | Prospective | Contras |

| NGAL | Proximal and distal tubular stress injury | AUC: 0.88 (0.84-0.90); sensitivity 0.82, specificity 0.81[57] | Early marker of tubular injury; predictive of nephropathy before albuminuria | Larger-scale, standardized prospective studies are needed to implement uNGAL as a biomarker into routine clinical use | Detects injury before traditional biomarkers; non-invasive and stable in urine | Not specific for DKD; elevated in infections or AKI; limited validation (small sample size studies only, high heterogeneity among studies in terms of results and methodologies) |

| KIM-1 | Proximal tubular injury | AUC: 0.85 (0.82-0.88); sensitivity 0.68, specificity 0.83[58] | Sensitive marker of early tubular injury in DKD; correlates with disease progression | Some promising data, but whether it can be used as a new marker for diagnosing DKD needs further investigation | Highly specific for proximal tubular damage; FDA-qualified for nephrotoxicity | Limited data in T1DM; limited validation (high heterogeneity between studies in terms of results and methodologies) |

| L-FABP | Lipid metabolism and proximal tubular stress | AUC: 0.97 (0.94-1.00); sensitivity 100%, specificity 86.67%[59] | Reflects oxidative and lipid-induced tubular damage | Available research seems to highlight high predictive power even compared to other urinary markers including microalbuminuria, but more studies are necessary in order to validate it as a standard biomarker | Sensitive to oxidative stress and useful for early diagnosis | Affected by diet and comorbidities (false positives); requires special assays; limited validation (small sample size studies only, high heterogeneity among studies in terms of results and methodologies) |

| MCP-1 | Inflammatory chemokine secreted by monocytes and macrophages | AUC: 0.546 (0.453-0.638); sensitivity 67.3%, specificity 50.0%[60] | Correlates with tubulointerstitial inflammation and progression of DKD | May not be sufficient as a standalone diagnostic marker for DKD | Correlates with inflammation and disease activity; useful in prognosis | Moderate sensitivity; poor-to-fair discrimination. Levels can fluctuate widely depending on the extent of kidney damage and the presence of inflammatory stimuli |

| Cystatin C | Proximal tubular function | AUC: 0.807 (0.741-0.873) sensitivity, 70.9%; specificity, 86.3%[61,62] | Indicates proximal tubular dysfunction; used in conjunction with serum cystatin C | Although not specifically approved as a stand-alone biomarker for DKD, it is well recognized as a valuable marker of kidney function and for assessment of overall kidney health, including in the context of DKD | Non-invasive, standardized assays available | Affected by inflammation, corticosteroids, thyroid dysfunction and infections (false positives); not highly specific |

| Creatinine | Muscle metabolism and tubular function | AUC: 0.604-0.8[63] | Used to normalize other urinary biomarkers; reflects kidney filtration but not specific | Limited diagnostic value alone; rarely used; not FDA approved | Readily available, useful for comparative purposes | Not specific or sensitive for kidney damage (it reflects filtration rather than damage); limited diagnostic value alone |

| Fe Mg | Tubular magnesium handling | No data on AUC, sensitivity, or specificity | Early sign of tubular reabsorption impairment | May not be sufficient and specific as a diagnostic biomarker of DKD | Potential early tubular dysfunction marker; measurable in clinical laboratories | Lack of standardization, diagnostic accuracy data, and large-scale validation (limited sample sizes, no established cut-offs) |

| Angiotensinogen | RAAS activity | No data on AUC, sensitivity, or specificity | Reflects intrarenal RAAS activity; elevated in DKD and hypertension | uAGT remains a candidate “theragnostic” biomarker predicting response to RAAS inhibition; further rigorous studies are needed to determine its potential diagnostic role in DKD | Correlates with DKD severity; reflects RAAS dysregulation | Values can be influenced by sex hormones (false positives). Overlap with systemic RAAS activation; requires careful interpretation. Lack of external validation (lack of diagnostic accuracy data, small sample size studies) |

| Periostin | Tubular fibrosis | AUC: 0.78 (0.71-0.86); sensitivity 80.7%, specificity 43.3% (for a cut-off value of 1.01 ng/mg Cr)[64] | Associated with tubular injury and fibrosis; elevated in early DKD | Still sparse, although consistent body of research regarding its role as an early biomarker of DKD | Reflects fibrotic transformation early; may guide interventions | Emerging marker; limited clinical validation and availability (small and cross-sectional studies). Role not clear in early DKD |

| Uromodulin | Thick ascending limb health | Regarding the ability to discriminate between patients with DKD and patients with CKD without diabetes, AUC-ROC for the urinary glycated uromodulin (glcUMOD) resulted in 0.715 (0.597-0.834)[65]; urinary uromodulin with an AUC of 0.81 (sensitivity 80%, specificity 60%) and exosomal UMOD gene expression with an AUC of 0.95 (sensitivity 92%, specificity 84%) are elevated in early DKD[66] | Lower levels associated with increased mortality risk and DKD progression | glcUMOD could represent a novel biomarker for DKD; determination of the clinical value of glcUMOD requires further study | Inverse association with outcomes; not expressed in damage; potentially protective marker | Not a direct damage marker; interpretation depends on clinical context; the limited research has focused on its translational modification (glcUMOD) |

| EGF | Tubular epithelial regeneration | Regarding the association between lower uEGF to creatinine ratio with new-onset eGFR < 60 mL/minute per 1.73 m2: In T2DM normoalbuminuric patients: AUC-ROC: 0.85 (0.81-0.90)[67] | Involved in tubular repair | Low uEGF to creatinine ratio could serve as a biomarker of progressive renal function deterioration in normoalbuminuric patients | Inverse marker (lower levels predict DKD progression); decreases before clinical deterioration | Not routinely measured, lack of sufficient validation |

| VDBP | Vitamin D transport, liver and tubular cells | No data on AUC, sensitivity, or specificity. Significantly elevated in diabetics with normal, micro- and macroalbuminuria compared to controls, in stepwise fashion (SMDs: 1.52, 1.81, and 1.51, respectively; all P < 0.00001)[68] | Elevated in DKD; correlates with albuminuria and tubular injury | uVDBP could be a promising tubular injury biomarker but requires formal accuracy studies on larger scale | Strong correlation with DKD progression; measurable with multiplex assays | Lack of specificity; also elevated in other renal pathologies (false positives); lack of diagnostic accuracy data and established cut-offs |

| RBP4 | Tubular stress, adipocytes | AUC: 0.746 (0.659-0.834), sensitivity 84.6%, specificity 62.5%[69] | Associated with tubular stress and insulin resistance in DKD | Predictive role of urinary RBP4 requires further investigation, with most studies involving circulating/serum RBP4 | Associated with metabolic stress and insulin resistance; useful in early DKD | Limited normative data; influenced by obesity (false positives); it may be complementary in the diagnosis of early DKD |

| YKL-40 | Inflammation and remodeling (monocytes and chondrocytes) | It seems associated with a greater risk of kidney function decline and mortality on a limited male cohort[70] | Elevated in DKD; linked to mortality and inflammation | Serum/plasma YKL-40 predictive power of early DKD has been validated by multiple studies | Rise relevant in DKD | Emerging marker, lacks widespread validation |

NGAL: NGAL, a 25-kDa glycoprotein belonging to the lipocalin family, is covalently bound to gelatinase from human neutrophils and expressed by epithelial cells including those in the kidney. It is notably released by both granulocytes and proximal and distal tubular epithelial cells under ischemic, toxic, or inflammatory stress conditions[71]. In the context of acute kidney injury, NGAL synthesis in the distal and proximal tubule is rapidly and massively upregulated, leading to a quick increase in its urinary concentrations, which often precede the rise in serum creatinine; early elevations in urinary NGAL (uNGAL) are therefore predictive of nephrotoxic and/or ischemic kidney injury[72]. It is worth noting that uNGAL increases not only in conjunction with renal tubular damage, but also in bacterial infections, severe systemic inflammatory responses, and chronic diseases, limiting its specificity[73].

In the context of DKD, tubular damage often precedes glomerular injury, implying the relevance of uNGAL as an emerging biomarker for early detection of the disease, even before the onset of incipient nephropathy[74]. uNGAL could predict the development of albuminuria and may be utilized as a noninvasive indicator for diagnosing, staging, and monitoring the progression of DKD[75].

A recent cross-sectional study by Varatharajan et al[76] proved uNGAL to be significantly elevated in normoalbuminuric diabetic patients when compared to healthy subjects, suggesting this particular biomarker could predict DKD even before to the onset of microalbuminuria, with a sensitivity and specificity of 75.8% and 55%, respectively; these findings are consistent with the results of several previous studies. Most notably, Tang et al[57] formerly conducted a meta-analysis of fourteen observational studies published between 2008 and 2019, indicating NGAL as a preliminary marker of DKD, with reported pooled sensitivity and specificity of 96% and 89%, respectively, in three cohort studies, as compared with 82% sensitivity and 81% specificity in eleven cross-sectional studies. Subsequently, Quang et al[77] found that NGAL had a sensitivity and specificity of 60% and 70%, respectively, in predicting the early stages of DKD, with a cut-off value of 35.2 ng/mL. In addition, Phanish et al[78] described NGAL as a useful biomarker for progressive CKD in nonalbuminuric subjects, suggesting a potentially relevant role of proximal tubular injury and inflammation[79] in the pathophysiology and advancement of DKD. More recently, a systematic review by Karimi et al[80] characterized NGAL as a valuable indicator of initial renal damage in DKD, providing higher sensitivity and specificity compared to proteinuria; furthermore, Kashgary et al[81] conducted a retrospective case-control study corroborating the diagnostic value of NGAL as an early urinary biomarker of DKD, with a sensitivity and specificity of 100% at a cut-off value of 322.5 pg/mL. It is worth noting that the vast majority of available research seems to confirm the value of NGAL as a preliminary indicator of DKD. However, a study by Kim et al[82] questioned its early diagnostic usefulness, as urinary concentrations did not to differ significantly between normoalbuminuric patients and healthy controls.

UNGAL could not only serve as an early indicator of disease, but also as a marker of damage progression[83,84], as indicated by the research from Siddiqui et al[85], which showed a positive correlation between uNGAL levels and progressive kidney impairment. In this context, Duan et al[86] highlighted a higher risk of nephrotic-range proteinuria along with unfavorable renal outcomes in T2DM patients with higher concentrations of uNGAL. As stated by Satirapoj et al[87], uNGAL levels significantly correlate with eGFR decline and higher serum creatinine, providing further evidence of the prominent role that tubulointerstitial changes play in progressive DKD. In a post-hoc analysis of the VA NEPHRON-D trial[88], Chen et al[70] observed that higher baseline uNGAL was independently associated with a 10%-40% increase in the risk of all-cause mortality in a cohort of DKD patients, while a large-scale study by Ide et al[89] followed 2685 DKD patients over a 5-year period, proving uNGAL levels to significantly predict eGFR deterioration in albuminuric subjects. Nevertheless, Chou et al[90] on the one hand, and Rotbain Curovic et al[91] on the other failed to determine a negative correlation between uNGAL and kidney function; it is then safe to affirm that additional high-quality, prospective studies involving larger populations are needed to draw definite conclusions and advance our understanding of uNGAL as a predictor of DKD progression.

Most of the research evaluating the diagnostic and prognostic value of NGAL in DKD was conducted in T2DM-affected populations, implying a shortage of validation in T1DM. Interestingly, a recent meta-analysis involving children and adolescents with T1DM demonstrated uNGAL as an accurate and reliable biomarker for early detection of T1DM-related kidney disease in pediatric populations[92]. However, a previous study by Valent Morić et al[93] did not find a significant difference in uNGAL levels between pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes and healthy controls, suggesting that NGAL should be used cautiously and not as the sole marker for DKD in children and adolescents.

Notably, there is a limited body of research examining the association between uNGAL levels and renal histopathological changes assessed by kidney biopsy. A prospective analytical study from Garg et al[94] demonstrated a statistically significant correlation between urinary NGAL concentrations and morphometric indicators of renal injury in DKD patients, specifically the extent of chronic inflammatory cell infiltration and glomerular sclerosis. These results support the potential utility of uNGAL as a biomarker for personalized management of DKD, facilitating treatment stratification according to underlying disease activity and histological severity.

KIM-1: KIM-1, also known as hepatitis A virus cellular receptor 1 or T-cell mucin domain-1, is a type I transmembrane glycoprotein, belonging to the immunoglobulin and T-cell mucin domain family. Under normal physiological conditions, it is minimally expressed in the kidneys. However, upon proximal tubular injury, due to ischemic, toxic, or inflammatory insults, its expression is markedly upregulated on the apical membrane of proximal tubular epithelial cells. The extracellular portion can split and rapidly enter the tubular lumen after renal injury and then be detected in urine. It has been confirmed that the level of KIM-1 in urine is closely related to the level of KIM-1 in tissue and correlated with renal tissue injury. KIM-1 has not only been shown to be an early biomarker of acute kidney injury but also has a potential role in predicting long-term renal outcome.

Several human studies indicate that tissue expression and urinary excretion of the KIM-1 ectodomain are sensitive and specific markers of injury, as well as predictors of outcome[95]. Recent data suggest that KIM-1 expression has a protective effect during early injury, while in chronic disease, prolonged KIM-1 expression may be maladaptive and could represent a target for the therapy of CKD[96]. In DKD, tubular damage often precedes glomerular injury, and urinary KIM-1 (uKIM-1) has emerged as a potential early marker of the disease as well as a prognostic marker; elevated uKIM-1 levels have been independently associated with increased all-cause mortality in patients with CKD and diabetes, even after adjusting for traditional risk factors such as eGFR and albuminuria[97]. This aligns with recent findings from the chronic renal insufficiency cohort study, which identified KIM-1 and chitinase-3-like protein-1 (also known as YKL-40) as predictors of adverse outcomes in DKD, even after multivariate adjustment.

Furthermore, insulin resistance is a known contributor to DKD onset and progression; a study involving normoalbuminuric patients with T2DM demonstrated that higher insulin resistance, assessed by the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance, correlates with increased uKIM-1 levels; this biomarker can serve as an early indicator of renal tubular injury associated with insulin resistance, even in the absence of glomerular involvement[98].

A Chinese case-control study of 129 patients (101 patients with diabetes vs 28 healthy controls) showed significantly higher uKIM-1 levels in diabetic patients: [120.0 (98.4-139.9) ng/g creatinine vs 103.1 (86.8-106.2) ng/g creatinine]; However, no differences were found between normoalbuminuric, microalbuminuric and macroalbuminuric subgroups, nor was a statistically significant correlation observed with eGFR or uACR, indicating potential limitations in CKD stage discrimination[99].

El-Ashmawy et al[100] performed a cross-sectional study involving 60 diabetic patients, with serum creatinine higher than 2 mg/dL, and 20 healthy controls. Similar to previous studies, uKIM-1 levels were ten-fold higher in diabetic microalbuminuric patients compared to control and normoalbuminuric diabetic patients; also, KIM-1 positively correlated with creatinine, urea, body mass index, microalbuminuria and duration of disease; it was negatively correlated with eGFR. Similar results were found in another independent diabetic cohort by Aslan et al[101].

Notably, Kin Tekce et al[102] also showed how KIM-1 levels change among the different stages of CKD, with levels being higher in stage II (2962 ± 724) compared to stage III (2168 ± 642) (P = 0.025) and IV (1765 ± 483) (P = 0.021). More importantly, a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial[103] studied the utility of KIM-1 in the progression of DKD. At baseline, KIM levels were higher in patients with microalbuminuria [143.5 (98-225)] and macroalbuminuria [281 (186-474)] compared to those in normoalbuminuric [97 (64-145)] patients. Subsequently, KIM-1 was statistically significantly associated with kidney outcome only in unadjusted analysis, but lost significance in the fully adjusted model (hazard ratio = 1.4; KIM 95% confidence interval: 1.0 to 1.9; P = 0.07).

A study aimed to highlight the clinical value of urinary biomarkers using Luminex liquid suspension chip technology. 737 patients were recruited: 585 with DM and 152 with DKD. Propensity score matching of demographic and medical characteristics identified a subset of 78 patients (DM = 39, DKD = 39). It was revealed that urinary levels of vitamin D-binding protein, retinol-binding protein 4 and KIM-1 were significantly higher in the DKD group than in the DM group (P < 0.05), while the levels of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1, TNF receptor (TNFR)-1, TNFR-2, alpha 1-microglobulin (α1-MG), β2-MG, cystatin C (CysC), nephrin and epidermal growth factor were not significantly different between the groups. This underscores the diagnostic value of uKIM-1 and other selected tubular biomarkers over conventional glomerular indicators in distinguishing early DKD[40].

Liver-type fatty acid-binding protein: Liver-type fatty acid-binding protein (L-FABP) is a cytoplasmic low molecular weight (15 kDa) carrier protein predominantly synthesized and expressed in the proximal tubules of the kidney and the liver. It plays a crucial role in the intracellular transport and metabolism of fatty acids. In the context of DKD, urinary L-FABP (uL-FABP) has emerged as a sensitive biomarker reflecting early tubular injury, often preceding detectable changes in albuminuria[59]. The study by Zhang et al[104] reported significantly higher uL-FABP concentrations in individuals with normoalbuminuria compared to healthy controls, suggesting its potential as an early indicator of renal tubular dysfunction in DKD. Furthermore, uL-FABP levels have been shown to correlate negatively with eGFR and positively with the albumin-to-creatinine ratio, highlighting its association with both glomerular and tubular damage. Additionally, a recent study by Chen et al[105] emphasized the role of uL-FABP in reflecting tubulointerstitial injury, independent of albuminuria, and its potential in assessing the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions in DKD. The clinical relevance of uL-FABP is further underscored by its association with cardiovascular outcomes. A long-term observational study by Araki et al[106] found that higher urinary levels of L-FABP were associated with deteriorating renal function and a higher incidence of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetic patients without advanced nephropathy, suggesting its role in predicting future renal and cardiovascular events. In conclusion, uL-FABP serves as a promising biomarker for the early detection and monitoring of DKD. Its ability to reflect tubular injury independent of albuminuria, coupled with its associations with renal function and cardiovascular outcomes, underscores its potential clinical utility in managing patients with diabetes at risk of nephropathy.

MCP-1: MCP-1, or CCL2 is a chemokine that plays a pivotal role in the recruitment of monocytes, macrophages, and other immune cells to sites of inflammation. Studies have demonstrated that MCP-1 contributes to the progression of renal injury by promoting immune cell infiltration and fibrosis in various kidney diseases, including DKD[107]. MCP-1 is upregulated and highly expressed in the glomerular and renal tubular epithelium in diabetes, with an increase in urinary MCP-1 levels correlating with interstitial inflammatory infiltration and renal tissue macrophage accumulation[108]. Serum MCP-1 levels are occasionally elevated in diabetic patients, although this increase does not correlate with albuminuria, kidney macrophage accumulation, or nephropathy development. In contrast, urinary MCP-1 levels closely reflect kidney MCP-1 production and significantly correlate with albuminuria, serum glycated albumin, urine N-acetylglucosaminidase, and kidney cluster of differentiation 68 + macrophages in both human and experimental DKD[107]. On this matter, Titan et al[109] demonstrated that urinary MCP-1, together with retinol-binding protein, independently predicts renal outcomes in macroalbuminuric DKD, underscoring their value in risk stratification beyond conventional clinical markers such as albuminuria and eGFR. Furthermore, another study by Fufaa et al[110] provided evidence that elevated urinary MCP-1 levels are associated with early DKD lesions in T1DM, reinforcing MCP-1’s role as a biomarker of incipient renal damage before overt clinical manifestations. In conclusion, urinary MCP-1 might be a promising biomarker for early detection and prognosis of DKD, reflecting renal inflammation and predicting disease progression beyond traditional markers.

Urinary CysC: CysC is a cysteine proteinase inhibitor; in a healthy condition, this molecule is almost freely filtered by the renal glomeruli, so the urinary CysC (uCysC) is, in a healthy patient, absent and there is no tubular secretion of CysC, even if we consider the differences among the population (e.g., age or muscle mass). This value is affected by thyroid dysfunction, corticosteroids, and inflammation[111]. Zeng et al[112] performed a consecutive cohort study where they highlighted that uCysC was elevated in T2DM and DKD patients before the outbreak of albuminuria and with a normal uACR. Higher uCysC levels resulted from chronic tubular damage, which can be detected earlier using this marker. Thus, uCysC can predict the progression of T2DM patients with DKD. Furthermore, it is fundamental to underline that T2DM patients with rapid DKD progression show significantly increased levels of uCysC compared with the non-rapid progression group and uCysC levels are positively correlated with uACR in both diabetes and prediabetes: UCysC may play a major role in the early diagnosis of DKD in prediabetes[113]. It is important also to evaluate urinary leakage of other proteins [non-albumin protein (NAP)]. Kim et al[114] in a prospective observational study demonstrated that uCysC was increased in patients with macroalbuminuria, independently of serum CysC. In addition, it showed that NAPs, which include α1-MG, β2-MG, IgG, transferrin nephrin, matrix metalloproteinase-9 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1, are stronger predictors for renal and tubular damage than uCysC. They might be considered in the prediction of renal impairment, and in normoalbuminuric patients[115].

Urinary creatinine: Urinary creatinine (UCr) is another biomarker that might be associated with tubular damage, a dysfunction that occurs in diabetic patients. Several studies focused on the possibility that UCr is an early predictor of DKD. Cao et al[116], in their retrospective cross-sectional analysis, observed a non-linear relationship between UCr and DKD. In particular, the risk of developing DKD seems to decrease when UCr is below a threshold of 17421 mmol/L. This information is important because it highlights that UCr represents the compensatory function of the kidneys. As soon as UCr is above this level, there is a positive correlation with DKD progression[117]. This indicates that creatinine excretion increases when damage occurs and renal stress is exacerbated. A combined approach, using UCr with uACR and eGFR, might lead to more accurate risk stratification in DKD patients. In addition, Sinkeler et al[118] showed that creatinine excretion ratio was inversely proportional to risk for mortality of diabetic patients, this statement indicates that the creatinine excretion rate can be used as a risk marker in the diabetic population.

Fractional excretion of magnesium: Hypomagnesemia is a frequently observed biochemical abnormality in patients with T2DM and has been associated with poor glycaemic control, insulin resistance, and the progression of microvascular complications[119]. While serum magnesium levels provide a snapshot of systemic magnesium status, they may not fully capture early renal tubular alterations. In this context, the fractional excretion of magnesium (Fe Mg) emerges as a potential marker of tubular dysfunction, offering additional insight into the subclinical stages of DKD. The Fe Mg is an indicator of the excretion process of magnesium through the renal tubules. It is calculated as the percentage of serum Mg excreted through urine and its normal value is less than 4%. Therefore, Fe Mg could be considered a tubular function index: Its value increases in correlation with the chronicity of the tubulointerstitial damage. On this matter, Fe Mg might correlate with the clinical severity of DKD. In fact, it has been shown in the normoalbuminuric stage of T2DM that the mean value of Fe Mg was 4.1% ± 1%, conversely in the albuminuric stage of disease, Fe Mg was increased to 6.6% ± 2%. Moreover, an inverse correlation between Fe Mg and the reduction of peritubular capillary flow has also been demonstrated[120]. Consequently, Fe Mg could be regarded as a potential urinary biomarker of early tubular damage in DKD.

Urinary angiotensinogen: Renal angiotensinogen is predominantly synthesized by proximal tubular epithelial cells and secreted into the tubular lumen. Recent evidence implicates activation of the intrarenal renin-angiotensin system (RAS) in the pathogenesis and progression of renal injury across various models of hypertension and in kidney diseases such as DKD. Studies have demonstrated that, in the early stages of T2DM with normoalbuminuria, urinary angiotensinogen (uAGT) levels are elevated compared to healthy controls and exhibit strong discriminatory power in distinguishing different stages of T2DM from non-diabetic individuals[121]. Consequently, uAGT has been proposed as a sensitive early biomarker of intrarenal RAS activation in DKD. Notably, a multicenter prospective study by Jeon et al[122] provided compelling evidence supporting the clinical utility of uAGT as a surrogate marker for predicting the antiproteinuric effects of angiotensin receptor blockers in patients with overt proteinuria. The study showed that higher baseline uAGT levels, as well as short-term changes in uAGT following angiotensin receptor blocker initiation, were significantly associated with the degree of proteinuria reduction. This finding suggests that uAGT may serve not only as a biomarker of intrarenal RAS activity but also as a predictor of therapeutic responsiveness to RAAS blockade, offering a valuable tool for tailoring treatment strategies in patients with DKD. Moreover, de Alencar Franco Costa et al[123] revealed sex-dependent differences in renal angiotensinogen expression in diabetic models, with female animals showing a heightened intrarenal angiotensinogen response compared to males. These findings point to a potential influence of sex hormones on RAS activation and raise the possibility that uAGT levels could serve as an early marker of DKD with differential diagnostic and prognostic implications between sexes. Altogether, these studies reinforce the role of uAGT as an early, dynamic, and potentially personalized biomarker for monitoring renal involvement and guiding therapy in DKD.

Periostin: Periostin is a matricellular protein primarily localized in connective tissues, especially in the bone. Its expression in the kidney is transient during embryonic development and virtually undetectable in normal adult renal tissue. In DKD, however, periostin expression is markedly upregulated in both glomerular and tubular epithelial cells reflecting its involvement in renal fibrotic processes and tissue remodeling. Urinary periostin levels are significantly elevated in patients with DKD, regardless of albuminuria status compared to healthy controls[121]. This finding highlights the potential of urinary periostin as an early and sensitive biomarker of renal injury. Supporting this, a study by Satirapoj et al[64] demonstrated that urinary periostin excretion was significantly increased in patients with T2DM and correlated positively with the degree of albuminuria and the progressive decline in eGFR. Moreover, their results suggest that periostin may not only reflect ongoing renal damage but could also play a pathophysiological role in the progression of DKD through mechanisms involving extracellular matrix remodeling and fibrosis. Consequently, periostin represents a promising non-invasive biomarker for early detection and monitoring of diabetic renal injury, with potential implications for risk stratification and therapeutic targeting.

Uromodulin: Uromodulin, also known as Tamm-Horsfall protein, is the most abundant protein in normal human urine and is synthesized by the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle. Recent studies have highlighted its emerging role as a biomarker in various kidney diseases, including DKD and in the progression of CKD. Takata and Isomoto[124] recently highlighted the important roles of uromodulin in maintaining kidney homeostasis, such as regulating ion transport and protecting against inflammation, positioning it as a promising biomarker for CKD. As uromodulin is produced exclusively in the kidney thick ascending limb, its levels in urine and serum closely reflect nephron mass and renal function. Urinary uromodulin, in fact, correlates positively with eGFR and urine volume but decreases with age and diabetes. This suggests that uromodulin reflects tubular function independently from glomerular filtration markers and may increase per functioning nephron under stress. Notably, higher serum uromodulin is linked to slower kidney decline and less albuminuria in high-risk patients, while low levels can identify early kidney injury before creatinine rises. On this matter, Leiherer et al[125] demonstrated that patients with T2DM exhibited significantly lower serum uromodulin levels compared to non-diabetic controls, and that levels were highest in those who remained normoglycemic throughout follow-up. Furthermore, urinary uromodulin concentrations tend to decline in the presence of macroalbuminuria, reinforcing its potential utility in detecting tubular impairment associated with diabetes[126]. This is supported by Chakraborty et al[127] who highlighted altered expression patterns of Tamm-Horsfall protein in diabetic patients with kidney damage, suggesting that reduced uromodulin synthesis or increased urinary loss may reflect underlying tubular injury and dysfunction in diabetes. Moreover, recent findings indicate that glycated forms of urinary uromodulin are present in early-stage DKD, and their levels correlate with disease severity, pointing to potential applications in early diagnosis and disease monitoring[65]. Overall, uromodulin is a valuable biomarker for tubular health, kidney mass, and predicting CKD progression, especially in diabetes-related renal disease.

Considerations on the diagnostic accuracy of the main urinary DKD markers: Early identification of DKD is essential to delay progression toward end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Traditional markers such as uACR/albuminuria and eGFR, although widely used, have notable limitations, mainly their inability to detect subclinical renal injury and their delayed rise in disease course. Many patients, particularly those with type 2 diabetes, may develop significant renal damage without presenting elevated albumin levels, a condition termed NADKD. This diagnostic gap has spurred the search for more sensitive and specific urinary biomarkers that reflect earlier and broader aspects of kidney injury, including tubular stress, podocyte damage, and inflammatory processes.

For early DKD detection, evidence collected has shown that L-FABP and GPC-5 exhibited the highest diagnostic performance. NGAL and KIM-1 also show strong early predictive capability, especially for tubular injury which may precede albuminuria. In detail, L-FABP demonstrated outstanding diagnostic performance, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.97, 100% sensitivity, and 86.7% specificity, making it one of the most accurate early indicators of DKD. GPC-5, a marker of podocyte injury, showed a sensitivity of 93.3% and specificity of 80%, and has emerged as a useful tool for identifying glomerular dysfunction before overt albuminuria appears. NGAL and KIM-1 are key tubular injury markers; both are elevated in normoalbuminuric diabetic patients, signaling early damage. NGAL shows pooled sensitivity and specificity above 80%, while KIM-1 displays an AUC of 0.85 and high specificity for proximal tubular damage.

Together, these biomarkers provide a more comprehensive picture of early DKD pathogenesis. Their integration into clinical practice could significantly enhance early diagnosis, allow better risk stratification, and guide personalized therapeutic strategies, particularly in patients not flagged by traditional tests.

Considerations on DKD markers in T1DM and T2DM: The performance and expression of urinary biomarkers can differ significantly between T1DM and T2DM due to distinct pathophysiological mechanisms, rates of disease progression, and comorbidity profiles. For example, the uACR is a standard marker for both types of DKD, but it tends to appear earlier and more consistently in T1DM, reflecting glomerular damage resulting from longstanding hyperglycemia. In contrast, a significant subset of T2DM patients presents with NADKD, making uACR a less reliable early marker in this group.

Another important difference is related to tubular DKD biomarkers (e.g., NGAL, KIM-1, L-FABP), that show better early predictive values in T2DM, especially for NADKD cases were albuminuria is absent; furthermore, T2DM patients often have higher baseline levels of tubular markers (NGAL, KIM-1, L-FABP), possibly due to coexisting hypertension, obesity, and systemic inflammation, which exacerbate tubulointerstitial injury. In T1DM, data are more limited, but recent pediatric and adolescent studies suggest that NGAL and KIM-1 may still offer early detection potential. Similarly, inflammatory markers (YKL-40, MCP-1) tend to be more elevated in T2DM, correlating with systemic inflammation and metabolic syndrome, which are more prevalent in T2DM.

Among the biomarkers associated with a better prediction in T1DM, podocyte injury agents (e.g., nephrin, podocalyxin, GPC-5) are relevant in both types of diabetes but appear more predictive in T1DM, where glomerular lesions are typically more pronounced and occur earlier. GPC-5 and nephrinuria have shown correlations with disease severity in both types, but standardization across populations is still needed.

Oxidative stress is a central pathogenic mechanism in DKD, contributing to endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, and fibrosis in renal tissues. Specifically, ROS induce epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of renal tubular cells through activation of signalling pathways such as phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B/glycogen synthase kinase-3β which can be attenuated by nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2-mediated heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) induction, thereby protecting against renal injury in a high-glucose environment[128].

Urinary biomarkers reflecting oxidative damage have gained prominence for their potential in the early diagnosis and monitoring of DKD progression. Among these, HO-1 has been shown to exert renal protective effects by modulating antioxidative responses and inhibiting apoptosis and inflammation, as demonstrated in both animal models and human studies[128,129]. Urinary HO-1 has been identified as a sensitive marker of renal oxidative stress. Li et al[40] demonstrated that urinary HO-1 levels were significantly elevated in patients with early-stage DKD, correlating with increased albuminuria and decreased GFR. This finding underscores the utility of HO-1 as an early biomarker for renal injury in diabetes. Other oxidative stress-related urinary biomarkers include 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG), pentosidine, and uric acid. 8-OHdG, a product of oxidative DNA damage, has been reported to correlate with the severity of DKD and microvascular complications in diabetic patients[105]. Measurement of urinary 8-OHdG by advanced electrochemical biosensors offers enhanced sensitivity and specificity, supporting its clinical utility in oxidative stress assessment[130]. The non-invasive nature of urine sampling and the specificity of these markers for oxidative damage highlight their clinical relevance in identifying patients at risk for DKD progression. Comparative analyses have demonstrated that urinary 8-OHdG levels correlate well with albumin-to-creatinine ratios and can serve as independent predictors of DKD onset, reinforcing their prognostic significance[131,132]. However, variations in detection methods and lack of standardized thresholds currently limit widespread clinical adoption[133].

Nevertheless, further longitudinal studies are necessary to validate their prognostic value and establish standardized thresholds for clinical application.

Since their discovery, an increasing body of evidence is positioning miRNAs as an attractive approach both as therapeutic targets[134] and for their intricate role in various diseases, such as cardiovascular disease[135], metabolic disorders[136], and cancer[137]. With regard to DKD, the dosage of miRNAs in the blood, urine, saliva, or tissues has shown potential as a biomarker for early detection of high-risk individuals, given that miRNAs contribute to the homeostasis of glucose and are involves in different physiological and pathological process[138].

Focusing on miRNAs detectable in the urine of patients, which can differ from the circulating ones and have attracted particular attention due to their non-invasive accessibility, several studies have evaluated their role and presence in DKD[139]. Indeed, a high number of miRNAs are still under investigation for their role in the various manifestation of DKD.

For example, the study by Petrica et al[140] explored the role of miRNA and long noncoding RNA (lncRNA). Specifically, they focused on miR-21 and miR-124, which have been proved to enhance podocyte injury and proximal tubule lesions, as well as miR-29 and miR-93, known for their protective function on podocyte, endothelial injury and renal fibrosis. In their study cohort, consisting of 136 patients with T2DM and 25 healthy controls, the downregulation of lncRNA myocardial infarction-associated transcript and lncRNA taurine-upregulated gene 1 was associated with increased expression of the protective miR-93 and miR-29a, and reduced activity of the pathogenic miR-21 and miR-124.

Another example of the potential of miRNAs can be found in the study by Zang et al[141], which profiled urinary exosomal miRNAs in 87 diabetic patients with and without impaired renal function. Their results showed that urinary miR-21-5p and miR-23b-3p were upregulated in patients with reduced renal function, while miR-30b-5p and miR-125b-5p expression was downregulated.

Moreover, the expression of miRNA can be linked to the levels of microalbuminuria. Indeed, miRNA in the studies by Zhao et al[142] with miR-4534 and Sinha et al[143] with miR-663a could be involved in the manifestation of microalbuminuria. In particular, Sinha et al[143] profiled urine miRNA from 25 patients stratified as non-proteinuric or proteinuric. Their findings showed different expression of miR-155-5p, miR-28-3p, miR-425-5p, and miR-663a in the two groups. Among these, notably, miR-663a downregulation was more pronounced in non-proteinuric than proteinuric DKD subjects, prompting the investigation of pathways and networks regulated by this miRNA with bioinformatics studies. Another relevant study on miRNA and microalbuminuria was carried out by Barutta et al[144]. In this study, miR-130a and miR-145 were significantly increased in DKD patients, while miR-155 and miR-424 were decreased in microalbuminuria patients compared to normoalbuminuric patients.

Another aspect of DKD in which miRNAs seem to be an actor are the levels of blood sugar and glycosylated hemoglobin. A recent study by Han et al[145] showed that miR-27a-3p was related to blood glucose, glycosylated hemoglobin, and cholesterol levels. Moreover, the same study proved that miR-27a-3p and miR-145-5p were positively correlated with albuminuria and serum creatinine and negatively correlated with the eGFR.

With regard to the role of miRNAs as therapeutic agents, different studies explored this opportunity ranging from in silico to in vivo experiments. In the study by Mishra et al[146], the authors tested whether restoring the down expressed miRNAs could attenuate DKD. They based their experiment on the observation that miRNAs, such as miR-24-3p and miR-200c-3p, which decline in renal tissue could contribute to disease progression. To test this, they injected the miRNAs via urinary exosomes in rats with DKD. Their results showed that treated rats had attenuated renal involvement and recovered expression of miRNAs. Notably, the renoprotective effects appeared to be independent of glucose-lowering, as the treatment did not affect the blood glucose levels. Although these findings are currently limited to animal models, detection of the same miRNAs in human patients supports the rationale for further investigation into their potential therapeutic role in human kidney disease. Another study, by Cho et al[147], analyzed urinary miRNAs in 64 patients undergoing treatment with either dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors or sulfonylureas, and found no significant difference in urinary miRNA expression between the two groups.

Collectively, all these studies support the hypothesis that urinary miRNAs show promise as early non-invasive biomarkers for predicting DKD and consequently miRNA-centred therapies, although still in the early stages of development, offer a potential target for new treatment strategies[148]. However, it is clear that more studies, especially prospective studies with more detailed clinical data are need to completely define the role of miRNAs and their potential as therapeutic targets.

Metabolomics is the study of metabolites, the end products of cellular processes, which include a wide range of substances such as amino acids, sugars, and lipids[149]. Metabolomic analysis typically focuses on metabolites found in biological fluids. The primary fluids studied are blood and urine, but other fluids such as saliva, seminal plasma, and cerebrospinal fluid can also be analyzed[150,151]. The principal technologies used in metabolomics are mass spectrometry (MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance[151]. Metabolomics is an emerging field and represents a promising strategy for the early detection of DKD[152], enabling the identification of DKD even in its initial stages[153].

Amino acids: Amino acids play an important role in glucose homeostasis by regulating the secretion of glucagon and insulin. The assessment of serum amino acid levels plays a key role in identifying potential biomarkers that may aid in early diagnosis. For instance, Wang et al[154] observed an increased risk of developing T2DM in patients with high plasma concentrations of isoleucine, leucine, valine, tyrosine, and phenylalanine. In opposition, Tofte et al[155] analyzed 637 patients with T1DM and found that isoleucine, leucine, and valine were positively associated with eGFR and a lower risk of ESRD. In support of this, Niewczas et al[156] observed progression of DKD in 80 patients in which 40 progressed to ESRD within 8-12 years. They found that higher levels of leucine and valine were associated with a reduced risk of developing ESRD, whereas elevated concentrations of phenylacetylglutamine and p-cresol sulphate were linked to disease progression. Phenylacetylglutamine and p-cresol sulphate are recognized as uremic toxins derived from altered gut microbiota metabolism, which is notably prevalent in CKD[157].

The differences in results across these studies can be explained by the variations in study design, populations, and clinical endpoints. While all three studies explore metabolomic predictors of diabetes and CKD, they employ distinct methodologies and focus on different patient groups. The study by Wang et al[154] was a nested case-control study that enrolled 2422 subjects at least 35 years old with no history of diabetes or cardiovascular disease, who also underwent an oral glucose tolerance test as part of the Framingham heart study. In this population, the authors identified branched-chain and aromatic amino acids as strong predictors of future T2DM, independent of traditional risk factors. In contrast, Niewczas et al[156] and Tofte et al[155] studied 80 patients with T2DM and 637 with T1DM, respectively, at risk of ESRD. Indeed, unlike Wang’s study[154], which focused on predicting diabetes onset in healthy individuals, the studies by Niewczas et al[156] and Tofte et al[155] shift the focus towards patients already affected by diabetes. The presence of diabetes in their cohorts could have already altered their metabolic phenotype. Moreover, their studies focused on renal outcomes (e.g., ERSD and CKD progression), which could also be influenced by the systemic metabolic disturbances typical of CKD pathophysiological mechanisms. Additionally, the sample sizes varied considerably among the studies and may have influenced the statistical power and the ability to detect or generalize metabolomic associations.

Serum analysis provides valuable insights and should not be underestimated; however, the investigation of biomarkers in urine is gaining increasing attention due to its non-invasive nature and potential for early disease detection. Shao et al[158] analyzed the metabolic profiles of 88 patients, 44 with DKD and 44 with only T2DM. They compared biomarker differences between the two groups and identified 61 serum metabolites and 46 urinary metabolites. In the DKD group, the levels of benzoic acid, fumaric acid, erythrose, and L-arabitol were significantly higher than in the T2DM group. Conversely, levels of glycerol 1-octadecanoate, L-glutamic acid/pyroglutamic acid, fructose 6-phosphate, taurine, and L-glutamine were significantly reduced in DKD patients. In addition, DKD patients showed significantly elevated urinary levels of D-glucose, L-valine, L-histidine, sucrose, gluconic acid, glycine, L-asparagine/L-aspartic acid, L-xylonate-2, and oxalic acid compared with T2DM patients. To improve the predictive utility of metabolites to diagnosis DKD, Pena et al[159] compared urine and plasma metabolites. They observed that in T2DM patients with microalbuminuria there was a reduction in plasma histidine and an increase of butenoylcarnitine, and low hexose, glutamine and tyrosine in urine. Thus, these parameters could predict the progression of albuminuria, independent of eGFR and baseline albuminuria.

In a study involving a cohort of 1001 participants at various stages of DKD, Kwan et al[160] reported that elevated urinary levels of 3-hydroxybutyrate, a metabolic intermediate of valine catabolism, were associated with a more rapid decline in eGFR and an increased likelihood of requiring renal replacement therapy. Similarly, Li et al[161] identified a reduction in urinary levels of several metabolites in DKD patients, including aconitic acid, isocitric acid, 4-hydroxybutyrate, uracil, and glycine. Both studies suggest that the decrease in mitochondrial-derived metabolites reflects a broader suppression of mitochondrial activity in the context of DKD.

Tyrosine is an important amino acid biomarker, produced through the hydroxylation of phenylalanine-by-phenylalanine hydroxylase. In patients with DKD, both urinary and serum levels of tyrosine can serve as indicators of disease progression[162]. Zhang et al[163] found that elevated plasma tyrosine levels are associated with an increased risk of developing DKD, while Liu et al[164] reported that lower urinary tyrosine levels correlate with the presence of DKD. In opposition, Tofte et al[165] observed that elevated levels of tyrosine are associated with increased eGFR, and other studies reported the positive association between downstream metabolites of tyrosine and ESKD[166].

Another biomarker involved in DKD is tryptophan, an aromatic amino acid that is altered in this condition[167]. Renal insufficiency leads to an increase in kynurenine, a downstream metabolite of tryptophan, which in turn promotes leukocyte activation, cytokine production, oxidative stress, and inflammation[168]. Reinforcing the potential role of tryptophan as a biomarker, Mogos et al[169] in a case-control study compared 3 types of patients (normoalbuminuric, microalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria) and healthy patients. They reported a reduction in serum tryptophan in patients, while urinary tryptophan was lower in normoalbuminuric patients than in the other groups. Furthermore, they observed a reduction in urinary glycine with the progression of DKD. Van der Kloet et al[170] found that urinary acyl-glycines and intermediates of tryptophan metabolism were positively correlated with albuminuria and associated with the progression of DKD. Similarly, Chou et al[171] observed that tryptophan metabolism is disrupted in patients with T2DM, with lower plasma tryptophan levels being significantly associated with a more rapid decline in eGFR.

Other amino acids investigated as potential biomarkers for DKD include norvaline, an isomer of valine, and aspartate. In a study by Tavares et al[172] both were inversely associated with DKD progression. Similarly, Hirayama et al[173] reported that aspartate levels were inversely correlated with eGFR and positively associated with albuminuria. Furthermore, Mogos et al[169] supported the involvement of various urinary metabolites in DKD progression, particularly urinary aspartate, which may reflect localized kidney damage at specific segments of the nephron.

Lipids: Lipids play a key role in several metabolic processes related to diabetes, including dyslipidaemia and insulin resistance[174]. Numerous studies have confirmed the involvement of fatty acids and their metabolites in the pathogenesis of DKD[175].