Published online Dec 15, 2025. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v16.i12.115435

Revised: November 8, 2025

Accepted: November 18, 2025

Published online: December 15, 2025

Processing time: 60 Days and 3.8 Hours

This editorial comments on the study by Tao et al, emphasizing the scalable diag

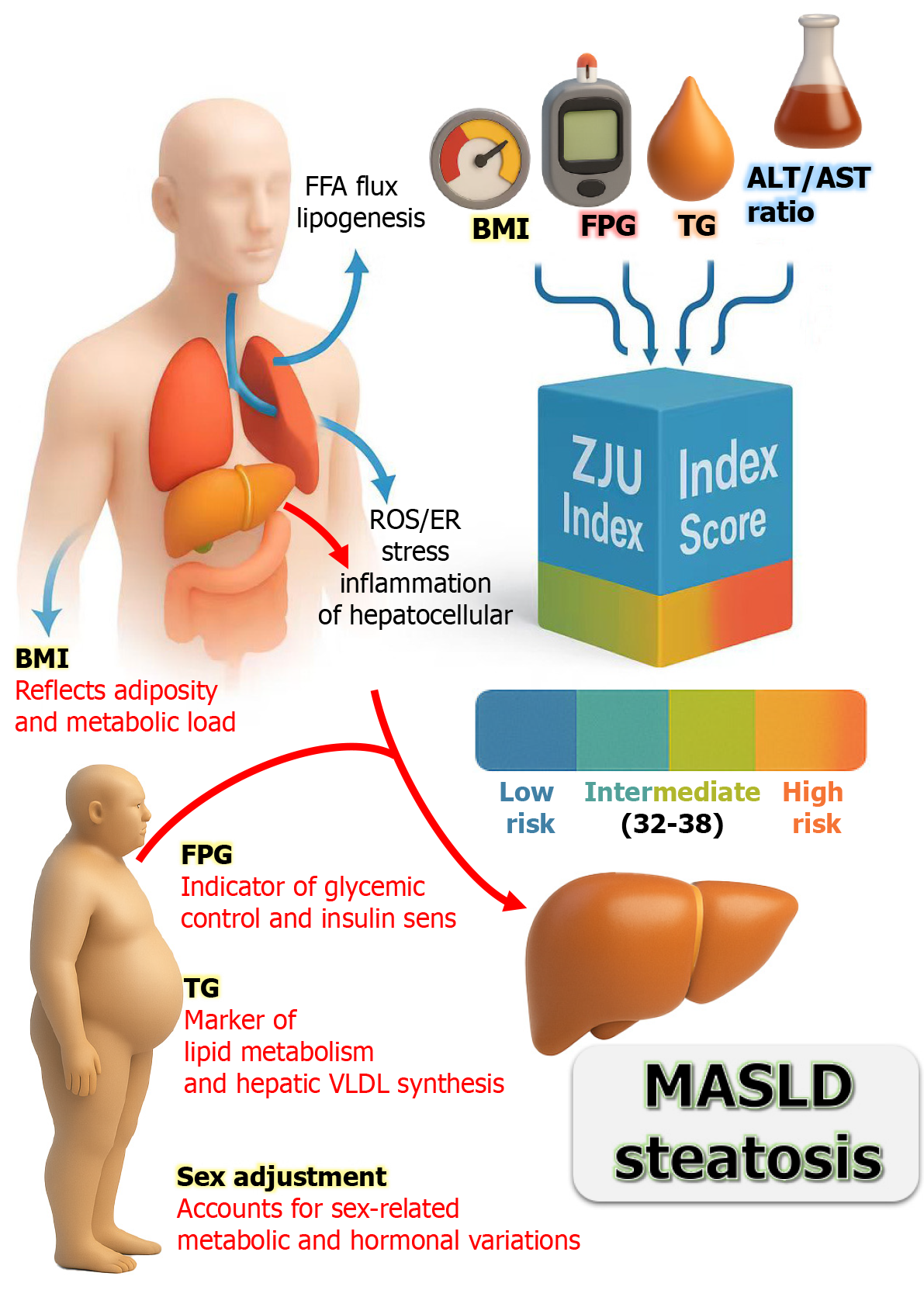

Core Tip: Early identification of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) in diabetes requires reliable and easily applicable tools. The Zhejiang University index (ZJU index) combines metabolic and hepatic parameters, such as body mass index, fasting glucose, triglycerides, and enzyme ratios, into a simple score derived from routine clinical data. Unlike traditional indices such as fatty liver index and hepatic steatosis index, the ZJU index demonstrates superior accuracy for detecting MASLD and correlates with systemic complications, including insulin resistance and sarcopenia. Its integration into electronic medical records enables automatic annual screening of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, providing a cost-effective, non-invasive approach for risk stratification and guiding timely preventive interventions.

- Citation: Gouda MM. From fatty liver indices to the Zhejiang University index: Re-shaping risk stratification of metabolic liver disease in diabetes. World J Diabetes 2025; 16(12): 115435

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v16/i12/115435.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v16.i12.115435

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a multi-system disease that predisposes individuals to diverse complications, notably metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) (formerly nonalcoholic fatty liver disease) and diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs)[1,2]. MASLD has become the most common chronic liver disease worldwide, affecting roughly one-quarter to one-third of adults, and its prevalence is even higher among people with T2DM. Recent meta-analyses estimate that approximately 65% of T2DM patients have fatty liver disease[3]. In parallel, DFUs represent a serious complication of diabetes, arising from a combination of peripheral neuropathy, ischemia, and impaired wound healing. They are a leading cause of infection and amputation in diabetic populations. While MASLD and DFUs manifest in different organs, they share common pathophysiological threads: Chronic inflammation, insulin resistance, and immune dysfunction are central to both conditions[3-5]. This convergence suggests that insights from one may inform the other, providing a holistic understanding of diabetic complications.

Over the past two decades, various non-invasive indices have been developed to detect and quantify hepatic steatosis in metabolic liver disease. These indices, including fatty liver index (FLI), hepatic steatosis index (HSI), Zhejiang University index (ZJU index), and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)-liver fat score (NLFS), distill clinical and laboratory variables into predictive scores for fatty liver[6,7]. By capturing key features of metabolic dysfunction (such as obesity, dyslipidemia, and liver enzyme elevations), the indices reflect underlying mechanisms of MASLD and offer practical screening tools. This shared pathophysiology underscores the systemic nature of diabetic complications, providing a valuable model for integrating metabolic assessment into diabetes care. For instance, the ZJU index combines fasting plasma glucose (FPG), triglycerides, and hepatic enzyme biomarkers that mirror these same metabolic pathways. An elevated ZJU index indicates a higher risk of MASLD and a broader metabolic burden that predisposes diabetic patients to vascular issues and impaired wound healing in DFUs.

This editorial presents an integrated comparative analysis of these two domains. It discusses the biological and pathophysiological mechanisms underlying MASLD indices in DFUs, with common mediators including inflammation, insulin resistance, and immune modulation. The clinical implications were emphasized, specifically how the ZJU index (as an exemplar MASLD score) could be utilized for risk stratification and management of fatty liver in T2DM. The global relevance of the ZJU index is highlighted, showing how metabolic liver indices can inform integrated diabetic care.

Metabolic dysfunction and insulin resistance are fundamentally driving MASLD. In insulin-resistant states, excess adiposity and hyperinsulinemia lead to increased free fatty acid flux to the liver and de novo lipogenesis, resulting in triglyceride accumulation in hepatocytes (steatosis). This process triggers cellular stress and mild hepatic inflammation, potentially progressing to steatohepatitis in some patients. Non-invasive indices for MASLD, such as FLI and HSI, capture these metabolic alterations[6,8]. The FLI integrates body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, triglycerides, and γ-glutamyl transferase, achieving an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of approximately 0.84 in detecting fatty liver[9,10]. Similarly, the HSI employs the alanine aminotransferase (ALT)/aspartate aminotransferase (AST) ratio, BMI, and adjustments for sex and diabetes, acknowledging their roles in liver injury[11]. Furthermore, the NAFLD liver fat score directly incorporates insulin resistance markers, demonstrating AUROC of 0.86-0.87 in correlating with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-measured liver fat, emphasizing the relevance of systemic metabolic dysregulation in hepatic steatosis[12,13]. It’s worth noting that an AUROC value of 1.0 indicates perfect dis

The ZJU index is a composite score that integrates metabolic and inflammatory signals in MASLD, developed within a large Chinese population. This index incorporates BMI, FPG, triglycerides, and the ALT/AST ratio (Table 1). Each component reflects aspects of MASLD pathophysiology: Adiposity (BMI), glycemic status (FPG), lipid metabolism (triglycerides), and hepatic enzyme changes (ALT/AST)[1,15]. The ZJU index demonstrated an AUROC of 0.822 for ultrasound-diagnosed NAFLD and approximately 0.896 for liver biopsy confirming ≥ 5% steatosis. A value < 32 exhibited 92% sensitivity for ruling out NAFLD, while a value > 38 achieved approximately 93% specificity for its diagnosis[16]. The study by Tao et al[1] reported that the ZJU index value of 38.87 was identified as the key threshold for diagnosing MASLD with good accuracy in comparison with the other metabolic indices alone [0.76, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.72-0.80]. This indeterminate range underscores the continuum of metabolic risk, necessitating clinical judgment or additional testing for values that fall within these thresholds. The integrated biomarkers in the ZJU index demonstrated superior diagnostic performance, elucidating the intricate relationship between metabolic and inflammatory pathways in MASLD[17].

| Index | Type | Formula | Key variables | Diagnostic cut-offs | Typical AUC | Ref. |

| FLI | Steatosis-related | 0.953 × e (0.139 × BMI + 0.718 × ln (TG) + 0.053 × GGT + 0.053 × WC - 15.745) | BMI, TG, GGT, WC | > 60 indicates hepatic steatosis; < 30 rules out | 0.82-0.85 | Clayton-Chubb et al[6]; Kaneva and Bojko[8] |

| HSI | Steatosis-related | 8 × (ALT/AST) + BMI (+ 2 if female) | ALT, AST, BMI, sex | ≥ 36 indicates steatosis; ≤ 30 rules out | 0.80-0.83 | Liu et al[7]; Chang et al[11]; Ahn[12] |

| ZJU | Steatosis-related | BMI (kg/m2) + FPG (mmol/L) + TG (mmol/L) + 3 × (ALT/AST) + (+ 2 if female; + 0 if male) | BMI, FPG, TG, ALT, AST, sex | ≥ 38 indicates NAFLD | 0.84-0.87 | Tao et al[1]; Zheng et al[15] |

| NLFS | Steatosis-related | -2.89 + 1.18 × MS + 0.45 × T2D + 0.15 × FBG + 0.04 × AST - 0.94 × (AST/ALT ratio) | MS, T2D, FBG, AST, ALT | > -0.64 indicates hepatic fat accumulation | 0.83-0.86 | Clayton-Chubb et al[6]; Liu et al[7] |

| FIB-4 | Fibrosis-related | [Age (years) × AST (U/L)]/[platelet count (109/L) × √ALT (U/L)] | Age, AST, ALT, platelet count | < 1.3 (low fibrosis); 1.3-2.67 (indeterminate); > 2.67 (advanced fibrosis) | 0.85-0.88 | Cusi et al[18] |

| NFS | Fibrosis-related | -1.675 + 0.037 × age + 0.094 × BMI + 1.13 × IFG/T2D + 0.99 × (AST/ALT ratio) - 0.013 × PLT - 0.66 × albumin | Age, BMI, AST, ALT, PLT, albumin, IFG/T2D | < -1.455 (low fibrosis); > 0.676 (advanced fibrosis) | 0.84-0.87 | Clayton-Chubb et al[6]; Liu et al[7]; Ahn[12]; Zhang et al[13] |

The indices for MASLD risk stratification in diabetes play a crucial role in the early identification of MASLD in patients with type 2 diabetes[18]. Patients with T2DM have a prevalence of fatty liver disease estimated at 55%-70%, which correlates with an elevated risk of progressive liver injury, including nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and fibrosis, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.82-0.83, and the risk rises sharply above 39[19]. However, routine liver imaging or biopsy for all diabetic patients is impractical and costly. Thus, non-invasive indices, such as the ZJU index, offer substantial therapeutic potential by facilitating risk stratification and informed management decisions.

The ZJU index has a particular advantage in T2DM management because it utilizes data typically collected during routine diabetes care, including BMI, fasting glucose, and liver enzymes (Figure 1). An elevated ZJU index serves as a critical indicator of underlying MASLD that might otherwise remain undetected. For example, a 55-year-old man with T2DM and obesity might present with a ZJU index of 40, indicating hepatic steatosis and prompting further investigation through liver imaging or fibrosis assessment. Identifying MASLD carries direct clinical implications, warranting interventions such as intensified weight loss efforts and optimization of glycemic control. In comparison, current guidelines from the American Diabetes Association and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases emphasize a strong suspicion for NAFLD in T2DM and advocate the use of non-invasive tests for fibrosis risk stratification. A practical “two-step” approach involves first detecting fatty liver through tools like the ZJU index and then assessing fibrosis risk with indices such as the fibrosis-4 index (FIB-4) or elastography. Where the FIB-4 index is calculated as in Table 1. Typical FIB-4 interpretation thresholds are: Values < 1.3 indicate a low probability of advanced fibrosis, 1.3-2.67 represent an indeterminate zone requiring further testing (e.g., elastography), and > 2.67 suggest a high probability of advanced fibrosis[18].

In this context, Tao et al[1] mentioned that the ZJU index can serve as a primary screening tool for every T2DM patient annually. Those with low values, such as < 32, can be reassured while still receiving lifestyle advice. Conversely, patients with intermediate or high values (≥ 38) would require further evaluation. By stratifying risk effectively, that index facilitates the allocation of specialized resources, including hepatologic referrals and consideration of emerging NASH therapies[3]. In addition, Wang et al[16] reported that at a value below 32.0, the ZJU index can exclude NAFLD with a sensitivity of 92.2% and 95%CI from 0.91 to 0.93. While at a value greater than 38.0, it could detect steatosis with a specificity of 93.3%. In that study, the ZJU index in patients with NASH or borderline NASH was significantly higher than in the no NASH group (P = 0.003). As a continuous score influenced by weight, glucose, and lipid levels, it reflects improvements in these parameters. Notably, patients who achieve significant weight loss or improved glycemic control may observe a drop in their ZJU index, indicating reduced liver fat. This decrease can reinforce adherence to lifestyle modifications. Moreover, a high ZJU index correlates strongly with insulin resistance and has been associated with an increased incidence of metabolic comorbidities. For instance, Tao et al[1] reported that individuals with elevated ZJU index face a higher risk of developing new-onset diabetes, suggesting its capacity to capture underlying metabolic risk that leads to cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease.

Although ZJU does not explicitly include blood pressure, its components align with the features of metabolic syndrome that contribute to vascular risk. Consequently, identifying a high ZJU index in diabetic patients warrants a thorough assessment of risk factors, including blood pressure control and lipid profiles, alongside aggressive man

Non-invasive indices such as FLI, HSI, ZJU, and NLFS mark a significant advancement in MASLD diagnostics. These indices utilize routine clinical data, presenting no additional cost or risk to patients (Table 1). Moreover, they allow for easy repetition over time to monitor disease progression. A 2025 external validation study by Zou et al[17] demonstrated that traditional NAFLD indices maintain effectiveness under the updated MASLD definition. This underscores that the index, based on metabolic factors, aligns with the new disease criteria that require the presence of metabolic risk factors. Consequently, they serve as robust tools adaptable to contemporary clinical practice.

Comparative studies reveal several limitations of steatosis indices, particularly their moderate sensitivity and specificity. Although FLI and ZJU can accurately identify steatosis at extreme values with approximately 90% accuracy, their predictive value diminishes in intermediate ranges[20]. This limitation poses a risk of either false reassurance or unnecessary treatment when they are used in isolation. Furthermore, these indices are primarily designed to detect hepatic fat but cannot assess liver disease severity. Patients with NASH or advanced fibrosis may present with similar index values as those with simple steatosis, which complicates clinical decision-making. Thus, identifying patients with significant fibrosis who require specialist referral and surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma becomes essential.

For fibrosis assessment, more specific tools like the NAFLD fibrosis score and FIB-4 are employed, alongside imaging techniques such as FibroScan[18]. Consequently, while steatosis indices are effective for initial screening, they necessitate supplementary fibrosis evaluations for comprehensive MASLD assessment. Moreover, generalizability is a notable concern, as ethnic and regional variations can influence index performance. The ZJU index demonstrated strong efficacy in a Chinese population, achieving an AUC of approximately 0.90 in a biopsy-validated cohort. In contrast, different populations may exhibit varying baseline enzyme levels or metabolic profiles, which can alter calibration. A study by Fu et al[21] involved severely obese North American women and indicated that the ZJU index remains a reliable NAFLD marker, albeit with different optimal cut-off values. They mentioned that the ZJU index showed the highest AUC (0.742) and a 95%CI from 0.647 to 0.837, compared to the HSI and other indices. This underscores the need for local validation studies, as recent research from 2022 to 2023 has compared numerous steatosis indices across various countries to assess their effectiveness.

Altogether, FLI is among the most reliable indices, likely due to its development on a large general population sample. In contrast, simpler indices, such as HSI, exhibit slightly lower accuracy. Notably, the ZJU index and Framingham steatosis index (FSI) sometimes outperform FLI in specific subgroups, with ZJU demonstrating the highest specificity in a Chinese quantitative computed tomography-based study[1]. The strength of both the ZJU and FSI lies in their incorporation of various metabolic dimensions, enhancing their predictive capabilities. For instance, FSI includes blood pressure, which introduces a cardiovascular risk factor and has been associated with predicting future cardiovascular events. Similarly, ZJU’s correlation with insulin resistance positions it as a valuable tool for predicting diabetes and metabolic syndrome outcomes. However, this multi-dimensionality can complicate calculations and interpretation, as FSI employs a logistic equation. Ultimately, in clinical settings, simpler models such as HSI or a nomogram for FLI are easier to implement. Nonetheless, the rise of digital health tools, including calculators and electronic medical records integration, addresses these challenges effectively[4].

The emergence of FLI, HSI, ZJU, and NLFS indices enables easy monitoring of disease progression over time. Zou et al[17] validated these indices effectiveness in MASLD diagnosis. In that study, the analysis of over 7700 subjects showed that FLI, HSI, and ZJU achieved AUROCs between 0.79 and 0.84, indicating excellent diagnostic performance. Thus, these indices, based on metabolic factors, align with new criteria that require metabolic risk assessments. However, com

In contrast, simpler indices such as HSI exhibit marginally lower accuracy. Notably, the ZJU index and FSI sometimes outperform FLI in specific subgroups, especially in terms of specificity. Both ZJU and FSI enhance predictive capabilities by incorporating various metabolic dimensions. Conversely, ZJU’s association with insulin resistance proves valuable for predicting diabetes and metabolic syndrome outcomes. Recent studies have explored novel diagnostic modalities for MASLD, with MRI-proton density fat fraction now regarded as a non-invasive gold standard for quantifying liver fat.

Quantitative ultrasound techniques, like controlled attenuation parameter on FibroScan, also provide reliable steatosis grading without biopsy. Although these imaging methods demonstrate high accuracy, their cost renders them impractical for large-scale screening of at-risk patients. As a result, indices are still essential for primary care screening. There is growing interest in biomarker panels combining enzymes with novel markers to detect NASH and fibrosis non-invasively. In practice, a diabetic patient could first be screened with the ZJU index for fatty liver, and if positive, subsequently undergo an enhanced liver fibrosis test or FibroScan to assess fibrosis. The integration of simple indices with advanced tests can create an efficient diagnostic pathway.

Due to the high prevalence of MASLD in T2DM patients, routine incorporation of the ZJU index into clinical practice is recommended. Automatic calculations during T2DM consultations are essential, especially for patients exceeding a threshold of 38-39, as this elevation indicates a significantly higher risk of MASLD. That index should be used alongside fibrosis markers like FIB-4 for comprehensive risk assessment. Patients with a high ZJU index and a FIB-4 score of ≥ 1.3 should be prioritized for liver stiffness assessment to facilitate timely intervention. Clear referral algorithms in primary care are necessary to streamline this process, with an annual ZJU index calculation proposed for T2DM patients to guide further evaluations. More importantly, the integration of the ZJU index into electronic medical records as an auto-calculated score is encouraged to promote proactive screening. While the ZJU index is supported as a significant risk marker for MASLD, further external validation across diverse populations is needed, as most data come from Chinese cohorts. Studies should explore its performance across varied ethnicities and regions, comparing it to imaging gold standards and novel biomarkers to establish diagnostic accuracy and enhance predictive capabilities.

The rise of MASLD is closely linked to the obesity and diabetes epidemics, particularly in Asia and the Middle East, where essential tools like FibroScan are often lacking. MASLD is becoming increasingly common among patients with T2DM, highlighting the need for early detection and personalized risk assessment. The ZJU index effectively identifies patients who need further evaluation in basic healthcare settings. This proactive approach enables general practitioners and endocrinologists to monitor liver health early, rather than waiting for severe damage to occur. That index utilizes metabolic parameters, including BMI, fasting glucose, triglycerides, and liver enzymes, demonstrating better sensitivity in Asian populations compared to traditional indices like FLI and HSI. Its straightforward application with routine clinical data makes it ideal for widespread screening in diabetic care. Incorporating the ZJU Index into electronic health records could shift liver assessments from reactive to preventive. Future research should explore its broader applicability and prognostic value.

| 1. | Tao XY, Pan TR, Zhong X, Pan XY. Association between Zhejiang University index and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. World J Diabetes. 2025;16:110406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Mallik S, Paria B, Firdous SM, Ghazzawy HS, Alqahtani NK, He Y, Li X, Gouda MM. The positive implication of natural antioxidants on oxidative stress-mediated diabetes mellitus complications. J Genet Eng Biotechnol. 2024;22:100424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 3. | Younossi ZM, Golabi P, Price JK, Owrangi S, Gundu-Rao N, Satchi R, Paik JM. The Global Epidemiology of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Among Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;22:1999-2010.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 93.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Shi M, Liu P, Li J, Su Y, Zhou X, Wu C, Chen X, Zheng C. The performance of noninvasive indexes of adults in identification of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children. J Diabetes. 2021;13:744-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fife CE, Horn SD, Smout RJ, Barrett RS, Thomson B. A Predictive Model for Diabetic Foot Ulcer Outcome: The Wound Healing Index. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2016;5:279-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Clayton-Chubb D, Commins I, Roberts SK, Majeed A, Woods RL, Ryan J, Schneider HG, Lubel JS, Hodge AD, McNeil JJ, Kemp WW. Scores to predict steatotic liver disease - correlates and outcomes in older adults. NPJ Gut Liver. 2025;2:9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Liu Y, Liu S, Huang J, Zhu Y, Lin S. Validation of five hepatic steatosis algorithms in metabolic-associated fatty liver disease: A population based study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;37:938-945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kaneva AM, Bojko ER. Fatty liver index (FLI): more than a marker of hepatic steatosis. J Physiol Biochem. 2024;80:11-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Grinshpan LS, Even Haim Y, Ivancovsky-Wajcman D, Fliss-Isakov N, Nov Y, Webb M, Shibolet O, Kariv R, Zelber-Sagi S. A healthy lifestyle is prospectively associated with lower onset of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Hepatol Commun. 2024;8:e0583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bedogni G, Bellentani S, Miglioli L, Masutti F, Passalacqua M, Castiglione A, Tiribelli C. The Fatty Liver Index: a simple and accurate predictor of hepatic steatosis in the general population. BMC Gastroenterol. 2006;6:33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1238] [Cited by in RCA: 2212] [Article Influence: 110.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chang JW, Lee HW, Kim BK, Park JY, Kim DY, Ahn SH, Han KH, Kim SU. Hepatic Steatosis Index in the Detection of Fatty Liver in Patients with Chronic Hepatitis B Receiving Antiviral Therapy. Gut Liver. 2021;15:117-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ahn SB. Noninvasive serum biomarkers for liver steatosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Current and future developments. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2023;29:S150-S156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zhang YX, Feng YP, You CL, Zhang LY. The diagnostic value of MRI-PDFF in hepatic steatosis of patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025;25:451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | He Z, Zhang Q, Song M, Tan X, Wang W. Four overlooked errors in ROC analysis: how to prevent and avoid. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2025;30:208-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zheng K, Yin Y, Guo H, Ma L, Liu R, Zhao T, Wei Y, Zhao Z, Cheng W. Association between the ZJU index and risk of new-onset non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in non-obese participants: a Chinese longitudinal prospective cohort study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024;15:1340644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wang J, Xu C, Xun Y, Lu Z, Shi J, Yu C, Li Y. ZJU index: a novel model for predicting nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a Chinese population. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zou H, Pan W, Sun X. Assessment of the diagnostic efficacy of five non-invasive tests for MASLD: external validation utilizing data from two cohorts. Front Nutr. 2025;12:1571487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cusi K, Abdelmalek MF, Apovian CM, Balapattabi K, Bannuru RR, Barb D, Bardsley JK, Beverly EA, Corbin KD, ElSayed NA, Isaacs S, Kanwal F, Pekas EJ, Richardson CR, Roden M, Sanyal AJ, Shubrook JH, Younossi ZM, Bajaj M. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD) in People With Diabetes: The Need for Screening and Early Intervention. A Consensus Report of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2025;48:1057-1082. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 68.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lee CH, Lui DT, Lam KS. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and type 2 diabetes: An update. J Diabetes Investig. 2022;13:930-940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Song K, Kwon YJ, Lee E, Lee HS, Youn YH, Baik SJ, Shin HJ, Chae HW. Optimal Cutoffs of Fatty Liver Index and Hepatic Steatosis Index in Diagnosing Pediatric Metabolic Dysfunction-associated Steatotic Liver Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;S1542-3565(25)00530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Fu CP, Ali H, Rachakonda VP, Oczypok EA, DeLany JP, Kershaw EE. The ZJU index is a powerful surrogate marker for NAFLD in severely obese North American women. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0224942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/