Published online Dec 15, 2025. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v16.i12.111771

Revised: August 6, 2025

Accepted: November 13, 2025

Published online: December 15, 2025

Processing time: 159 Days and 18.5 Hours

Akkermansia muciniphila (A. muciniphila) has been shown to have positive effects on various metabolic diseases and partially prevent the onset of spontaneous type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) in nonobese diabetic mice; however, its therapeutic efficacy in T1DM mice that have already developed T1DM remains unclear.

To assess the effects of A. muciniphila intervention on the intestinal barrier, immune parameters [regulatory T (Tregs) cells/T helper 1 cells balance, signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1)/nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) signal] and intestinal flora in a streptozotocin (STZ)-induced mouse model of T1DM.

Thirty male C57BL/6 mice were randomized into three groups (n = 10 for each): Normal control (NC group), STZ-induced T1DM (STZ group), and A. muciniphila-treated T1DM (A. muciniphila group). T1DM was induced with

Compared with STZ group alone, A. muciniphila group did not affect metabolic parameters. Histopathologically, STZ group and A. muciniphila group pancreatic islet cells underwent vacuolar degeneration and necrosis, exhibiting reduced counts and significantly decreased insulin positivity (P < 0.05 vs NC), with no intergroup differences. Flow cytometry and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay revealed elevated tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), and zonulin levels and decreased ZO-1 expression in STZ vs NC mice (P < 0.05). Compared with STZ alone, A. muciniphila group reduced TNF-α, TGF-β, and zonulin levels while increasing the CD4+/CD8+ ratio, FoxP3+ Tregs, interleukin-4, and ZO-1 (P < 0.05). Colonic NF-κB p65 expression was higher in STZ vs NC mice (P < 0.05), with no significant A. muciniphila group/NC difference after the intervention of A. muciniphila. The expression of NF-κB p65 in A. muciniphila group was lower than that in STZ group. STAT1 expression was lower in A. muciniphila vs STZ mice (P < 0.05). 16S sequencing revealed reduced Actinobacteria abundance in A. muciniphila vs STZ mice (P < 0.05).

Short-term intervention with A. muciniphila has shown positive effects on immune response parameters, ex

Core Tip: This study pioneers Akkermansia muciniphila (A. muciniphila) intervention evaluation in streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) mice. Despite no reversal of hyperglycemia or islet damage after short-term (3-day) oral administration, A. muciniphila ameliorated immune imbalance by enhancing intestinal barrier function (increased zonula occludens-1, decreased zonulin), suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interferon-gamma), increasing anti-inflammatory interleukin-4 and regulatory T cells, modulating signaling pathways (reduced signal transducer and activator of transcription 1, suppressed nuclear factor kappa-B p65), and decreasing intestinal Actinobacteria abundance. These findings highlight A. muciniphila’s potential for immune regulation in established T1DM by gut barrier repair and microbial shifts.

- Citation: Huang BJ, Guo S, Lin XY, Li YH, Ma HM, Zhang J, Chen QL. Oral Akkermansia muciniphila may ameliorates immune dysregulation in a murine model of streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetes. World J Diabetes 2025; 16(12): 111771

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v16/i12/111771.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v16.i12.111771

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) is a typical autoimmune disease, the core pathogenesis of which involves the abnormal activation of cluster of differentiation (CD) 4+ and CD8+ effector T cells[1]. Among them, CD8 T cells are recognized as the core effector cells that mediate the destruction of islet β cells. CD4+ T cells participate in immune regulation by differentiating into T helper (Th) 1, Th2, regulatory T (Tregs) cells and other functional subsets. Th1 cells mainly secrete pro-inflammatory factors such as interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) to dominate cellular immunity, and Th2 cells negatively regulate immune response through anti-inflammatory factors such as interleukin (IL)-4[1]. In addition, Tregs, as key maintainers of immune tolerance, induce immune tolerance by secreting inhibitory factors such as transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β). The functional defects and excessive activation of Th1 cells are regarded as one of the cores immunopathological mechanisms of T1DM pathogenesis[2].

It is worth noting that the imbalance of intestinal microbial homeostasis and the destruction of the intestinal barrier play important roles in the immune disorder of T1DM. Zonulin is the only known physiological regulator of intercellular tight junctions, and its overexpression will prolong the opening time of tight junctions, resulting in increased intestinal antigen exposure[3]. Although zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) is not an essential component for maintaining the basic physical barrier, its downregulation will cause intestinal mucosal epithelial cell shedding and apoptosis, ultimately inhibiting effective cell proliferation and hindering intestinal mucosal repair[4]. Studies have shown that the intestinal flora of T1DM patients is characterized by a decrease in diversity, a decrease in the production of short-chain fatty acids by bacteria, and an abnormal increase in the intestinal barrier damage marker zonulin[5,6], suggesting that the interaction of microorganisms with the intestinal barrier and immune system may drive disease progression. In particular, the disruption of intestinal barrier integrity can activate the innate immune response through recognition receptors such as toll-like receptor (TLR)-4, inducing the activation of inflammatory signaling pathways such as the nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) pathway and promoting the production of islet β-cell autoantibodies[7,8]. This mechanism has been verified in the nonobese diabetic (NOD) mouse model, but there is still a significant gap in the study of bacterial intervention in the chemical-induced T1DM model.

As a key regulator of intestinal symbiotic bacteria, Akkermansia muciniphila (A. muciniphila) has shown positive the

The existing research on the intestinal flora of T1DM has two key limitations. First, A. muciniphila intervention studies have focused mostly on spontaneous models such as NOD. In the T1DM model induced by streptozotocin (STZ), there is a lack of systematic analysis of the regulatory network of NF-κB signaling and the Treg/Th1 balance. In addition to its advantages of low cost and a short modeling cycle, STZ-induced T1DM more closely approximates clinical T1DM in terms of pathological mechanisms such as autoimmunity and islet β-cell injury[14]. Second, although the A. muciniphila membrane protein Amuc_1100 has been shown to promote Treg differentiation through the TLR2/adenosine 5’-monophosphate-activated protein kinase pathway[15,16], it remains to be explored whether this protein can restore immune tolerance through the synergistic effect of signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) and NF-κB in the T1DM stage where irreversible damage to β-cells has occurred. The latest evidence shows that the STAT1 and NF-κB pathways are cross-regulated in autoimmune responses. STAT1 phosphorylation can increase the transcriptional activity of NF-κB, thereby amplifying the inflammatory signaling cascade[10], which provides a new direction for the study of the mechanism of A. muciniphila.

Based on these findings, this study proposes an innovative hypothesis: A. muciniphila may reshape the Treg/Th1 immune balance and restores intestinal barrier function by targeting the STAT1/NF-κB signaling axis, thereby alleviating metabolic disorders related to STZ-induced T1DM. After constructing an STZ chemical-induced T1DM model, this study integrated multidimensional techniques such as flow cytometry, immunoblotting, and 16S ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) sequencing to investigate the following: (1) The regulatory effect of A. muciniphila on the proportions of Treg/Th1 subsets and key cytokines [IL-4/tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α)] in the spleen; (2) The correlation between the expression of ZO-1/zonulin and the phosphorylation level of NF-κB p65 in colon tissue; and (3) The interaction between changes in the intestinal flora structure and the STAT1/NF-κB signaling pathway. The findings of this study not only provide a mechanistic basis for the application of A. muciniphila in the treatment of T1DM but also reveal a new target for the synergistic regulation of the STAT1/NF-κB pathway in the flora-immune axis.

Thirty specific pathogen free C57BL/6 male mice (purchased from the Experimental Animal Center of Sun Yat-sen University, ethical approval No. 2023001513), aged 4-6 weeks and weighing 15-20 g, were raised in the barrier laboratory of the Animal Experimental Research Center of the North Campus of Sun Yat-sen University; they were raised in independent ventilation cages, with no more than 5 mice in each cage. During this period, the mice were free to eat and drink. The ambient temperature was 20-24 °C, the relative humidity was 50%-70%, and the facility was illuminated on a 12 hour/12 hour alternating light/dark cycle. The mice in each group were fed a normal diet.

After 1 week of acclimation, the animals were randomly divided into a negative control (NC) group (n = 10), a STZ-induced T1DM (STZ group) (n = 10) and an A. muciniphila intervention group (n = 10). The mice in the STZ group and A. muciniphila group were intraperitoneally injected with 50 mg/kg/day STZ[17] for 5 consecutive days. The NC group was injected with an equal volume of 0.2 mL of solvent (citric acid buffer with a potential of hydrogen of 4.5). Each injection was performed after the animals had fasted for 12 hours. To detect hyperglycemia, the blood glucose level in tail vein blood was measured with a blood glucose meter every week. If the random blood glucose level was > 16.70 mmol/L[15] in two consecutive tests, the T1DM model was considered to be successfully established. In this study, all the STZ-treated mice successfully modeled T1DM.

Lyophilized A. muciniphila powder (ATCCBAA-835, purchased from the China General Microbiological Culture Collection and Management Center) was activated at 37 °C in a strictly anaerobic incubator (90% nitrogen, 10% hydrogen) with thioglycolate medium (purchased from Qingdao Haibo Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). After successful activation, 0.5 mL was taken for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification strain sequencing, 0.5 mL was added to 10 mL of liquid medium for fermentation treatment (4-5 days), and a blank control consisting of liquid medium was set up each time. In accordance with the methods of Wang et al[18], the fermented bacterial mixture was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 minutes, washed with anaerobic [phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)] and resuspended, and 100 μL of bacterial mixture was used to determine that an optical density 600 = 0.8 was equivalent to 1 × 108 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL. A. muciniphila (5 × 107 CFU/0.2 mL/mouse) was orally administered to the mice of A. muciniphila group for 3 consecutive days, and the NC group and the STZ group were given an equal volume of anaerobic PBS. After the intervention, under sterile conditions, fresh feces were collected by the stress defecation method and stored at -80 °C. The mice were then anesthetized with isoflurane and sacrificed by cervical dislocation. The abdominal cavity was opened, and the tail of the pancreas (the islet-rich part) was placed in 4% paraformaldehyde fixative at room temperature for 48 hours for pathology. The spleen and colon were removed and placed in frozen PBS for use.

The following resources were used: STZ (Sigma, United States), sodium citrate buffer (Shanghai Zeta Company, China), a hematoxylin-eosin staining kit (Wuhan Sevier Biological Company, China), 4% paraformaldehyde fixative (Wuhan Sevier Biological Company, China), an anti-insulin mouse mAb (Wuhan Sevier Biological Company, China), an anti-mouse CD4-fluorescein isothiocyanate antibody (Hangzhou Lianke Biological Company, China), an anti-mouse CD8-APC antibody (Hangzhou Lianke Biological Company, China), an anti-mouse forkhead box P3 (FoxP3)-PE antibody (Hangzhou Lianke Biological Company, China), a purified anti-mouse CD16/32 antibody (Hangzhou Lianke Biological Company, China), a mouse IgG1 isotype control-PE antibody (Hangzhou Lianke Biological Company, China), mouse fluorescence-activated cell sorting concentrate (4 ×) and diluent (Hangzhou Lianke Biological Company, China), rabbit anti-mouse STAT1 polyclonal antibodies (Wuhan Sevier Biotechnology Company, China), rabbit anti-mouse NF-κB p65 polyclonal antibodies (Wuhan Sevier Biotechnology Company, China), a goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin secondary antibody (Wuhan Sevier Biotechnology Company, China), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (for TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-10, TGF-β, ZO-1 and zonulin; Shanghai Enzymatic Immunobiology Company, China), a DNA extraction kit (Kaijie, Germany), and a double-stranded DNA determination kit (Sigma, United States).

Body weight and random blood glucose levels in tail vein blood were measured at specified times of each week, and the difference in the drinking water reserves of each mouse cage at a specified time from one day to the next was measured once to determine water intake.

To evaluate the effect of A. muciniphila on mouse islets, islets fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 hours were removed, and 2 μm paraffin sections were prepared. Hematoxylin-eosin staining and anti-insulin immunohistochemical staining were performed, and the results were analyzed pathologically.

To determine the contribution of Tregs to mouse autoimmunity, fresh spleens were collected immediately after sacrifice to prepare single-cell suspensions. The expression of CD4, CD8 and FoxP3 was determined by flow cytometry, and the isotype control group was used. In addition, the cytokine profiles (TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-4, and TGF-β) of the mouse spleen were determined by ELISA.

To determine the intestinal mucosal repair function and intestinal barrier changes in mice[4,19], the expression levels of ZO-1 and zonulin in the colons of the mice were determined by ELISAs. The greater the level of ZO-1 is, the lower the level of zonulin, indicating that the intestinal mucosal repair function and barrier function are stronger.

To explore the signaling pathways involved in the role of A. muciniphila in autoimmunity, we assessed the target proteins of NF-κB and STAT, which are important components in immune stress pathways[20,21]. The colons fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 hours were removed to prepare 3 μm paraffin sections for the immunohistochemical staining of NF-κB p65 and STAT1. The histochemical score[22] of the staining results for the mucosal layer was determined; that is, the ratio of positive cells and their staining intensity in each slice were transformed into corresponding values to semiquantitatively analyze the strength and frequency of positive signal in immunostained tissue. The histochemical score ranged from 0 to 300. The greater the value is, the stronger the comprehensive intensity (depth) of positivity and the greater the number of positive cells.

Fresh feces were collected by stress defecation, after which genomic DNA was extracted from the feces. Specific primers (PCR amplification primer sequence: Forward primer: 5’-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCA-3’; Reverse primer: 5’-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3’) were used to perform PCRs on the V3 and V4 regions of the bacterial 16S rRNA, aiming to characterize the composition and structure of the gut microbiota. The thermal cycle consisted of initial denaturation at 98 °C for 5 minutes; 25 cycles of denaturation at 98 °C for 30 seconds, annealing at 53 °C for 30 seconds, and extension at 72 °C for 45 seconds; and a final holding step at 72 °C for 5 minutes. The PCR amplification products were purified with magnetic beads, and the double-stranded DNA was quantified. After a single quantitative step, the amplicons were collected in equal amounts, and the Illumina NovaSeq platform and a NovaSeq 6000 SP kit (total number of sequencing cycles: 500 cycles) were used for 2 × 250 bp high-throughput sequencing at Shanghai Parson Biotechnology Co., Ltd.

Alpha diversity, reflecting within-sample diversity, was assessed using the Simpson index (diversity), Shannon index (diversity), Chao1 index (richness), and Good’s coverage index (sequencing depth). Beta diversity, representing between-sample compositional differences, was visualized using principal component analysis (PCoA) based on the Bray-Curtis distance. Taxonomic composition was analyzed at both the phylum and genus levels. The relative abundances of the top 5-10 most abundant genera were compared across groups. Statistical differences in relative abundances of specific taxa (such as Actinobacteria, Verrucomicrobia, Allobaculum, Akkermansia, and Adlercreutzia) between groups were evaluated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (for normally distributed data) or the Kruskal-Wallis test (for non-parametric data).

When the data conform to normality, the data are expressed as means ± SD, otherwise it is expressed as median (interquartile range). The normality of the data was confirmed by the Shapiro-Wilk, and the homogeneity of variance was confirmed by the Bartlett or Brown-Forsythe test. Differences between groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA (normal distribution) or the Kruskal-Wallis test (nonparametric test), and Dunn’s correction was used for post hoc comparisons. If the data were normally distributed, Pearson correlation analysis was used; otherwise, Spearman correlation analysis was used. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 software.

To evaluate the effect of intestinal mucosal exposure to A. muciniphila on the clinical phenotype of T1DM, we measured the body weight, blood glucose level and water intake of the mice in each group every week during the experiment. At the second week of the experiment, the mice in the A. muciniphila group were orally supplemented with A. muciniphila bacterial mixture for 3 consecutive days to evaluate the pathological changes in their islets. The results were as follows (Figure 1).

Compared with those in the NC group, the body weights of the mice in the STZ and A. muciniphila group were significantly lower (P < 0.05) (Figure 1A); at the end of the experiment, there was no significant difference in body weight between the A. muciniphila and STZ group (Figure 1B). Compared with that of the NC group, the blood glucose levels of the STZ and A. muciniphila group were significantly greater (P < 0.05) (Figure 1B); at the end of the experiment, there was no significant difference in blood glucose between the A. muciniphila and STZ group. Compared with that of the NC group, the daily water intake of the STZ and A. muciniphila group increased significantly (P < 0.05) (Figure 1C). At the end of the experiment, there was no significant difference in the daily water intake between the A. muciniphila group and the STZ group, but the daily water intake of the A. muciniphila group showed a decreasing trend.

In terms of islet pathology, the results of hematoxylin-eosin staining (Figure 1D) revealed that the shape of the whole islet (black arrow) in the NC group was regular, round or oval and that the number of islet cells (green arrow) was high, the axis arrangement was roughly extended, and no obvious abnormalities were observed. In the STZ group, the volume of the islets (black arrow) decreased, the shape was irregular, and the cytoplasm of the islet cells (green arrow) was loose and lightly stained, indicating different degrees of vacuolar degeneration and necrosis. The number of islet cells was significantly reduced, and the arrangement was irregular. After oral supplementation with A. muciniphila, the pa

To clarify the regulatory effect of intestinal mucosal A. muciniphila exposure on Tregs in the systemic immune response, spleen T-cell subsets were detected by flow cytometry (Figure 2A-C). Although there was no significant difference in the ratio of CD4+/CD8+ T cells or the proportion of Tregs between the STZ group and the NC group, A. muciniphila intervention significantly increased the ratio (A. muciniphila group vs STZ group: P < 0.05) (Figure 2C), whereas the proportion of Tregs in the A. muciniphila group was significantly greater than that in the NC group (A. muciniphila group vs NC group: P < 0.05) (Figure 2B). There was no statistically significant difference in the proportions of Tregs between the A. muciniphila group and the STZ group.

The expression of TGF-β[23], the main effector of Tregs, was further assessed by ELISA (Figure 2D and E). The results revealed that the level of TGF-β in the spleen of the A. muciniphila group was significantly greater than that in the STZ group (A. muciniphila group vs STZ group: P < 0.05) and was positively correlated with the proportion of Tregs (r = 0.48, P < 0.05). These results suggest that A. muciniphila may enhance the immunosuppressive microenvironment by inducing Tregs to secrete TGF-β.

In addition, analysis of other cytokines in the spleen (Figure 2F-H) revealed that A. muciniphila intervention not only significantly reduced the levels of the proinflammatory factors TNF-α (A. muciniphila group vs STZ group: P < 0.05) and IFN-γ (A. muciniphila group vs STZ group: P < 0.05) in STZ-induced T1DM but also significantly increased the level of the anti-inflammatory factor IL-4 (A. muciniphila group vs STZ group: P < 0.05).

To clarify the effect of A. muciniphila intervention on pathway signals, we performed histochemical scoring of the colons of the mice (Figure 2I-L). The results revealed that the colonic NF-κB p65 score for the STZ group was significantly greater than that for the NC group (P < 0.05), whereas the score for NF-κB p65 in the A. muciniphila group was not significantly different from that in the NC group after the A. muciniphila intervention. The expression of NF-κB p65 in the A. muciniphila group was lower than that in the STZ group.

The results of the ZO-1 assay revealed that the expression of ZO-1 in the colon tissue of the STZ group was significantly lower than that in the NC group (P < 0.001) and that the expression of ZO-1 increased after A. muciniphila intervention (P < 0.001 vs the STZ group) (Figure 3A). Zonulin assays revealed that, compared with that in the NC group, the level of zonulin in the colon in the STZ group was significantly greater (P < 0.01) (Figure 3B) whereas the level of zonulin in the A. muciniphila group was significantly lower than that in the STZ group (P < 0.001) (Figure 3C).

To determine the effect of the intestinal mucosa on the distribution of the intestinal microflora after A. muciniphila exposure, we performed 16S rRNA analysis using the feces of each group of mice at the end of the experiment. The results were as follows (Figure 4).

Alpha diversity analysis: There were no significant differences in the Simpson, Shannon, Chao or coverage indices for the intestinal flora among the groups (Figure 4A).

β diversity analysis: PCoA (Figure 4B) revealed that the flora structures of the mice in the NC group and the STZ group were significantly different. After A. muciniphila intervention, the flora structure of the mice in the A. muciniphila group and the STZ group still exhibited certain similarities (repeated parts).

Relative abundance of intestinal flora in each group: At the phylum level (Figure 4C), Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Proteo

At the genus level (Figure 4F), the top 10 species in terms of the proportion of abundance changes were Lactobacillus, Oscillospira, Prevotella, Allobaculum, Ruminococcus, Flexispira, Coprococcus, Akkermansia, Adlercreutzia, and others, in that sequence. Compared with that in the NC group (Figure 4G), the relative abundance of Allobaculum in the STZ group and A. muciniphila group was significantly lower (P < 0.05, 0.04070 ± 0.04415 vs 0.05645 ± 0.02747). Compared with that in the NC group (Figure 4H), the relative abundance of Akkermansia in the STZ group and A. muciniphila group was significantly lower (all P < 0.05, 0.1158 ± 0.1364 vs 0.01356 ± 0.006094). Compared with that in the NC group (Figure 4I), the relative abundance of Adlercreutzia in the STZ group and A. muciniphila group was not significantly different (0.7655 ± 0.2393 vs 0.9375 ± 0.3078 vs 0.4483 ± 0.1685); compared with that in the STZ group, the relative abundance of Adlercreutzia in the A. muciniphila group was significantly lower (P < 0.05, 0.9375 ± 0.3078 vs 0.4483 ± 0.1685). There was no significant difference in the relative abundance of Lactobacillus, Oscillospira, Prevotella, Ruminococcus, Flexispira, Coprococcus or other genera.

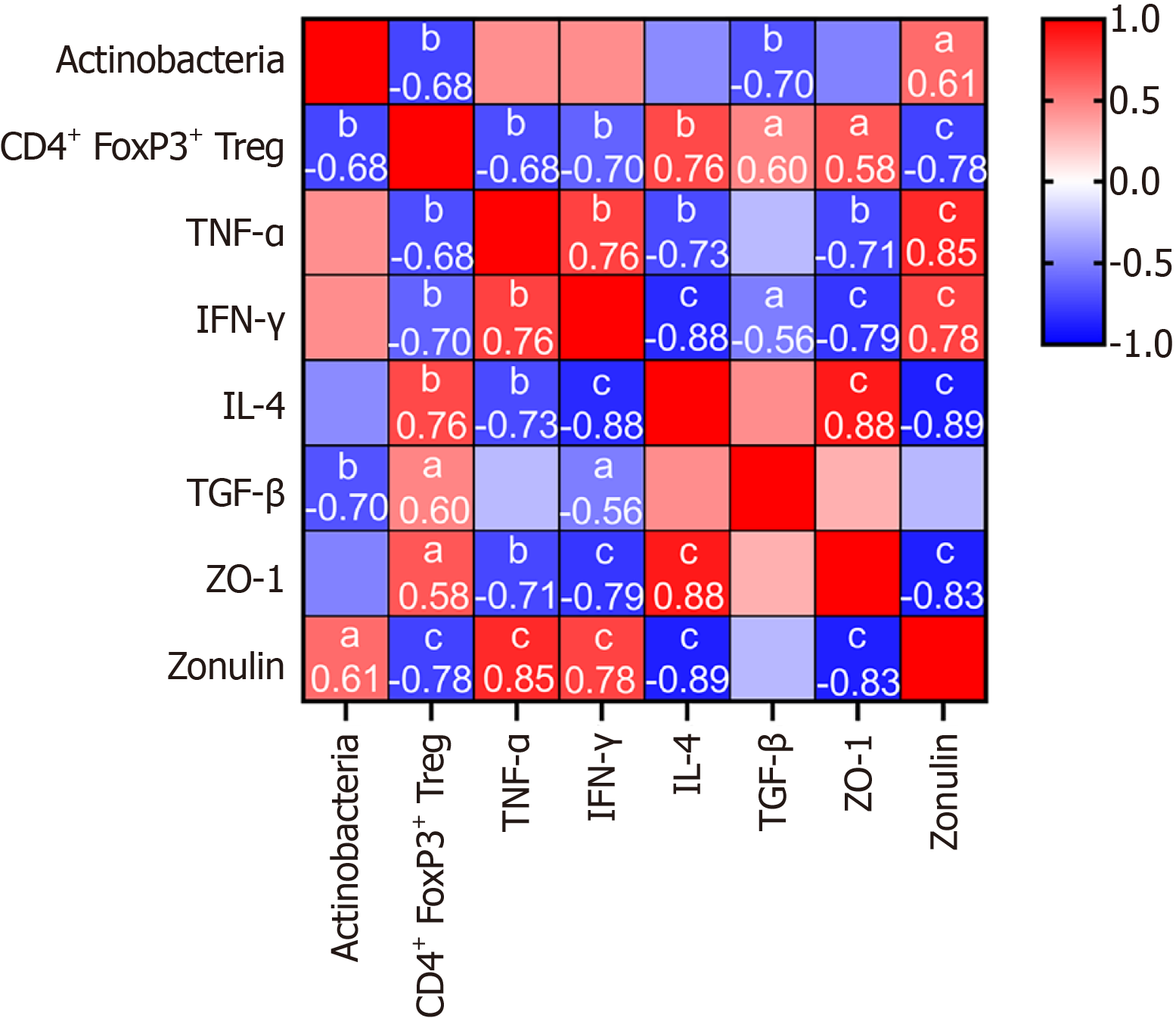

To determine the contributions of Tregs and the evolution of the flora distribution induced by A. muciniphila to systemic immunity and intestinal function, we analyzed the correlations between Tregs and Actinobacteria and between immune biochemistry and intestinal function. The results are as follows (Figure 5). The abundance of Actinobacteria was negatively correlated with the expression of CD4+ FoxP3+ Tregs and TGF-β and positively correlated with the expression of zonulin (all P < 0.05). CD4+ FoxP3+ Tregs were negatively correlated with actinomycete abundance and TNF-α, IFN-γ and zonulin expression and positively correlated with IL-4, TGF-β and ZO-1 expression; ZO-1 was negatively correlated with zonulin, TNF-α and IFN-γ expression and positively correlated with CD4+ FoxP3+ Tregs and IL-4 expression. The expression of zonulin was negatively correlated with the expression of CD4+ FoxP3+ Tregs, IL-4 and ZO-1 and positively correlated with the abundance of Actinobacteria, TNF-α and IFN-γ.

This study revealed the immunomodulatory effects of short-term A. muciniphila intervention on STZ-induced T1DM mice for the first time, filling the gap in existing research focused on preventive NOD models, such as Hänninen et al’s team[24]. Unlike the preventive intervention of Hänninen et al[24] in NOD mice, this study focused on the STZ model with dominant hyperglycemia. This model difference may explain the experimental finding that A. muciniphila failed to improve islet pathology but effectively regulated immune indicators.

Notably, Wang et al[18] reported that 3 days of A. muciniphila intervention alleviated dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis, whereas Plovier et al[25] reported that 4 weeks of A. muciniphila intervention in a type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) model significantly improved metabolic indicators. These findings suggest that in the T1DM model with irreversible β-cell damage, 3 days of A. muciniphila intervention is not enough to reverse the metabolic phenotype but may delay the progression of the disease through immune regulation. This finding is similar to the mechanism of action of immunomodulators reported by Ramos et al[26] to retain residual β-cell function in T1DM. Therefore, follow-up studies need to focus in two directions: First, whether A. muciniphila treatment with a longer intervention period or higher colonization concentration can achieve the effect of improving the metabolic state in a T1DM model similar to that of Plovier et al[25] in the T2DM model, or whether there is a threshold to reverse the effect; Second, the long-term persistence of the A. muciniphila colonization effect and its impact on disease outcome. It is worth emphasizing that the effective retention of residual β cells can not only reduce the demand for insulin use in patients with advanced T1DM but also show the potential to improve insulin sensitivity in T2DM research, which may also provide a potential strategy for optimizing insulin dose in patients with T1DM. In summary, the above phenomena suggest that the immunomodulatory effect of A. muciniphila may be independent of the direct repair of the islet microenvironment, and its mechanism of action has significant model dependence and time effect characteristics.

At the level of immune regulation, this study revealed a multidimensional regulatory mechanism (Figure 2). First, A. muciniphila significantly increased the proportion of splenic CD4+ FoxP3+ Tregs and the level of its effector TGF-β in the spleens and increased the ratio of CD4+/CD8+ T cells (Figure 2C) of the mice in A. muciniphila group, suggesting that A. muciniphila may improve immune homeostasis by reshaping the balance of T-cell subsets, which was consistent with the findings of Hänninen et al[24] in NOD mice, suggesting that Treg cell activation is the core pathway of A. muciniphila immune regulation. Although there was no significant difference in the proportions of Tregs between the A. muciniphila group and STZ group, the significant increase in TGF-β expression and its positive correlation with the proportion of Tregs (Figure 2E) suggested that the functional activation of Tregs may be earlier than the significant expansion of their numbers; therefore, a longer intervention period (such as > 2 weeks) may be more conducive to the accumulation of Treg numbers. Second, A. muciniphila intervention significantly downregulated the levels of the pro-inflammatory factors TNF-α and IFN-γ and upregulated the anti-inflammatory factor IL-4 (Figure 2F-H), indicating that it can reshape the Th1/Th2 balance and shift immune tolerance. This cytokine profile change may be due to Treg-mediated immunosuppression[1,23]. It is worth noting that A. muciniphila intervention significantly reduced the expression of STAT1 in the colon tissue of model mice (Figure 2L) and partially inhibited STZ-induced NF-κB p65 pathway activation (Figure 2J). Combined with its contribution to the downregulation of pro-inflammatory factors and previous studies[16,27,28], we speculate that the activation of the NF-κB p65 and STAT1 signaling pathways is involved in the pathogenesis of T1DM, which may weaken Treg function by promoting the transcription of inflammatory genes. This study found that A. muciniphila intervention can significantly downregulate the expression of key molecules in these two pathways, providing a new molecular target for elucidating its immune regulation mechanism.

In this study, abnormal intestinal permeability was observed in STZ-induced T1DM mice (Figure 3). Previous studies[29] showed that an impaired intestinal barrier could lead to the translocation of bacteria or their products into blood, aggravating the immune response or causing complications. Therefore, in this study, the improvement in intestinal barrier function may be the initiating factor for the immunomodulatory effect of A. muciniphila. This study confirmed for the first time that A. muciniphila intervention upregulates the expression of the tight junction protein ZO-1 and reduces the intestinal permeability marker zonulin in a T1DM model (Figure 3), and the two were significantly negatively correlated, supporting the pathological correlation between increased intestinal permeability and barrier protein destruction. More importantly, the A. muciniphila-mediated intestinal barrier repair effect (i.e., increased ZO-1 and decreased zonulin expression) was significantly positively correlated with Treg cell activation (ZO-1 r = 0.58, zonulin r =

At the level of flora structure, although A. muciniphila intervention had no significant effect on the diversity and richness of the overall community of intestinal flora (Figure 4A), PCoA showed that it could alter the structural changes of the intestinal flora induced by STZ (Figure 4B). Importantly, A. muciniphila intervention significantly reduced the abundance of Actinobacteria, and the abundance of Actinobacteria was negatively correlated with Treg cell activation (r = -0.68, P < 0.05). This finding has important implications: Although Actinobacteria contains beneficial bacteria such as Bifidobacterium, some members of Actinobacteria (such as Corynebacterium) may induce autoimmunity through molecular simulation mechanisms[34]. We speculate that this change may promote immune tolerance by inhibiting the STAT1/NF-κB pathway (Figure 2H-K), but its causality needs to be verified in a conditional gene knockout model. Moreover, strain-specific metabolome analysis was not performed in this study; therefore, the synergy of other symbiotic bacteria could not be ruled out. The results of this study suggest that A. muciniphila may regulate immunity by competitively inhibiting the growth of specific actinomycetes, but its causal relationship needs to be verified by fecal bacteria transplantation experiments.

Short-term intervention with A. muciniphila has shown positive effects on immune response parameters, exemplified by Treg-mediated restoration of immune tolerance, which may be associated with intestinal barrier enhancement and the decreased abundance of intestinal Actinobacteria.

Thank you for the experimental platform provided by the First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University.

| 1. | Bluestone JA, Herold K, Eisenbarth G. Genetics, pathogenesis and clinical interventions in type 1 diabetes. Nature. 2010;464:1293-1300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 861] [Cited by in RCA: 884] [Article Influence: 55.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ramírez-Valle F, Maranville JC, Roy S, Plenge RM. Sequential immunotherapy: towards cures for autoimmunity. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2024;23:501-524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wood Heickman LK, DeBoer MD, Fasano A. Zonulin as a potential putative biomarker of risk for shared type 1 diabetes and celiac disease autoimmunity. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020;36:e3309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kuo WT, Zuo L, Odenwald MA, Madha S, Singh G, Gurniak CB, Abraham C, Turner JR. The Tight Junction Protein ZO-1 Is Dispensable for Barrier Function but Critical for Effective Mucosal Repair. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:1924-1939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 346] [Article Influence: 69.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kostic AD, Gevers D, Siljander H, Vatanen T, Hyötyläinen T, Hämäläinen AM, Peet A, Tillmann V, Pöhö P, Mattila I, Lähdesmäki H, Franzosa EA, Vaarala O, de Goffau M, Harmsen H, Ilonen J, Virtanen SM, Clish CB, Orešič M, Huttenhower C, Knip M; DIABIMMUNE Study Group, Xavier RJ. The dynamics of the human infant gut microbiome in development and in progression toward type 1 diabetes. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:260-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 691] [Cited by in RCA: 891] [Article Influence: 81.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mønsted MØ, Falck ND, Pedersen K, Buschard K, Holm LJ, Haupt-Jorgensen M. Intestinal permeability in type 1 diabetes: An updated comprehensive overview. J Autoimmun. 2021;122:102674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Vaarala O, Atkinson MA, Neu J. The "perfect storm" for type 1 diabetes: the complex interplay between intestinal microbiota, gut permeability, and mucosal immunity. Diabetes. 2008;57:2555-2562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 371] [Cited by in RCA: 375] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Manfredo Vieira S, Hiltensperger M, Kumar V, Zegarra-Ruiz D, Dehner C, Khan N, Costa FRC, Tiniakou E, Greiling T, Ruff W, Barbieri A, Kriegel C, Mehta SS, Knight JR, Jain D, Goodman AL, Kriegel MA. Translocation of a gut pathobiont drives autoimmunity in mice and humans. Science. 2018;359:1156-1161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 576] [Cited by in RCA: 639] [Article Influence: 79.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cani PD, Depommier C, Derrien M, Everard A, de Vos WM. Akkermansia muciniphila: paradigm for next-generation beneficial microorganisms. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;19:625-637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 711] [Article Influence: 177.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Shi M, Yue Y, Ma C, Dong L, Chen F. Pasteurized Akkermansia muciniphila Ameliorate the LPS-Induced Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction via Modulating AMPK and NF-κB through TLR2 in Caco-2 Cells. Nutrients. 2022;14:764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Salem MB, El-Lakkany NM, Seif El-Din SH, Hammam OA, Samir S. Diosmin alleviates ulcerative colitis in mice by increasing Akkermansia muciniphila abundance, improving intestinal barrier function, and modulating the NF-κB and Nrf2 pathways. Heliyon. 2024;10:e27527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ganesh BP, Klopfleisch R, Loh G, Blaut M. Commensal Akkermansia muciniphila exacerbates gut inflammation in Salmonella Typhimurium-infected gnotobiotic mice. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 269] [Cited by in RCA: 391] [Article Influence: 30.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cekanaviciute E, Yoo BB, Runia TF, Debelius JW, Singh S, Nelson CA, Kanner R, Bencosme Y, Lee YK, Hauser SL, Crabtree-Hartman E, Sand IK, Gacias M, Zhu Y, Casaccia P, Cree BAC, Knight R, Mazmanian SK, Baranzini SE. Gut bacteria from multiple sclerosis patients modulate human T cells and exacerbate symptoms in mouse models. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:10713-10718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 502] [Cited by in RCA: 752] [Article Influence: 83.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Junod A, Lambert AE, Orci L, Pictet R, Gonet AE, Renold AE. Studies of the diabetogenic action of streptozotocin. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1967;126:201-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in RCA: 303] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Abdullah F, Khan Nor-Ashikin MN, Agarwal R, Kamsani YS, Abd Malek M, Bakar NS, Mohammad Kamal AA, Sarbandi MS, Abdul Rahman NS, Musa NH. Glutathione (GSH) improves sperm quality and testicular morphology in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Asian J Androl. 2021;23:281-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wang D, Li Y, Yang H, Shen X, Shi X, Li C, Zhang Y, Liu X, Jiang B, Zhu X, Zhang H, Li X, Bai H, Yang Q, Gao W, Bai F, Ji Y, Chen Q, Ben J. Disruption of TIGAR-TAK1 alleviates immunopathology in a murine model of sepsis. Nat Commun. 2024;15:4340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Qin Q, Chen Y, Li Y, Wei J, Zhou X, Le F, Hu H, Chen T. Intestinal Microbiota Play an Important Role in the Treatment of Type I Diabetes in Mice With BefA Protein. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:719542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wang B, Chen X, Chen Z, Xiao H, Dong J, Li Y, Zeng X, Liu J, Wan G, Fan S, Cui M. Stable colonization of Akkermansia muciniphila educates host intestinal microecology and immunity to battle against inflammatory intestinal diseases. Exp Mol Med. 2023;55:55-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Fasano A. Zonulin, regulation of tight junctions, and autoimmune diseases. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1258:25-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 222] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Clark DN, Begg LR, Filiano AJ. Unique aspects of IFN-γ/STAT1 signaling in neurons. Immunol Rev. 2022;311:187-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bui VH, Vo HN, Kim SK, Ngo DN. Caffeic acid-grafted chitooligosaccharides downregulate MAPK and NF-kB in RAW264.7 cells. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2024;103:e14496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yin JZ, Shi XQ, Wang MD, Du H, Zhao XW, Li B, Yang MH. Arsenic trioxide elicits anti-tumor activity by inhibiting polarization of M2-like tumor-associated macrophages via Notch signaling pathway in lung adenocarcinoma. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;117:109899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Biller BJ, Elmslie RE, Burnett RC, Avery AC, Dow SW. Use of FoxP3 expression to identify regulatory T cells in healthy dogs and dogs with cancer. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2007;116:69-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hänninen A, Toivonen R, Pöysti S, Belzer C, Plovier H, Ouwerkerk JP, Emani R, Cani PD, De Vos WM. Akkermansia muciniphila induces gut microbiota remodelling and controls islet autoimmunity in NOD mice. Gut. 2018;67:1445-1453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 276] [Article Influence: 34.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Plovier H, Everard A, Druart C, Depommier C, Van Hul M, Geurts L, Chilloux J, Ottman N, Duparc T, Lichtenstein L, Myridakis A, Delzenne NM, Klievink J, Bhattacharjee A, van der Ark KC, Aalvink S, Martinez LO, Dumas ME, Maiter D, Loumaye A, Hermans MP, Thissen JP, Belzer C, de Vos WM, Cani PD. A purified membrane protein from Akkermansia muciniphila or the pasteurized bacterium improves metabolism in obese and diabetic mice. Nat Med. 2017;23:107-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 967] [Cited by in RCA: 1573] [Article Influence: 157.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ramos EL, Dayan CM, Chatenoud L, Sumnik Z, Simmons KM, Szypowska A, Gitelman SE, Knecht LA, Niemoeller E, Tian W, Herold KC; PROTECT Study Investigators. Teplizumab and β-Cell Function in Newly Diagnosed Type 1 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:2151-2161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 49.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lim KH, Staudt LM. Toll-like receptor signaling. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5:a011247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 334] [Article Influence: 25.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Xue C, Yao Q, Gu X, Shi Q, Yuan X, Chu Q, Bao Z, Lu J, Li L. Evolving cognition of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway: autoimmune disorders and cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 383] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Compare D, Sgamato C, Rocco A, Coccoli P, Ambrosio C, Nardone G. The Leaky Gut and Human Diseases: "Can't Fill the Cup if You Don't Plug the Holes First". Dig Dis. 2024;42:548-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Spadoni I, Zagato E, Bertocchi A, Paolinelli R, Hot E, Di Sabatino A, Caprioli F, Bottiglieri L, Oldani A, Viale G, Penna G, Dejana E, Rescigno M. A gut-vascular barrier controls the systemic dissemination of bacteria. Science. 2015;350:830-834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 303] [Cited by in RCA: 544] [Article Influence: 49.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Turner JR. Intestinal mucosal barrier function in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:799-809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2121] [Cited by in RCA: 2829] [Article Influence: 166.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Jia L, Shan K, Pan LL, Feng N, Lv Z, Sun Y, Li J, Wu C, Zhang H, Chen W, Diana J, Sun J, Chen YQ. Clostridium butyricum CGMCC0313.1 Protects against Autoimmune Diabetes by Modulating Intestinal Immune Homeostasis and Inducing Pancreatic Regulatory T Cells. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Everard A, Belzer C, Geurts L, Ouwerkerk JP, Druart C, Bindels LB, Guiot Y, Derrien M, Muccioli GG, Delzenne NM, de Vos WM, Cani PD. Cross-talk between Akkermansia muciniphila and intestinal epithelium controls diet-induced obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:9066-9071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2639] [Cited by in RCA: 3468] [Article Influence: 266.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 34. | Chaurasia A, Meena BR, Tripathi AN, Pandey KK, Rai AB, Singh B. Actinomycetes: an unexplored microorganisms for plant growth promotion and biocontrol in vegetable crops. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018;34:132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |