Published online Dec 15, 2025. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v16.i12.110494

Revised: July 28, 2025

Accepted: November 3, 2025

Published online: December 15, 2025

Processing time: 190 Days and 15.2 Hours

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a significant risk factor for cardiovascular diseases and can worsen the risk of cardiovascular events among patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). However, strong evidence is needed to show the impact of DM on all-cause mortality (ACM) and atrial fibrillation (AF), which we ex

To determine the impact of DM on ACM and AF in patients with HCM.

PubMed, Google Scholar, and EMBASE databases were searched for studies showing the effect of DM on ACM and AF in HCM. A binary random effects model with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was used to pool odds ratios (ORs) for ACM and AF outcomes. Study quality was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute’s critical appraisal tool and leave-one-out sensitivity analysis. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Fourteen studies (n = 106138) with a mean age of 61.76 ± 19.84 years and 61.55% males were included in our systematic review; ten studies (n = 102882) were eligible for meta-analysis. In the unadjusted analysis, DM was not significantly associated with ACM (OR = 0.96; 95%CI: 0.43-2.15; P = 0.93). However, after adjustment, DM showed a significant association with higher ACM risk (adjusted OR = 1.37; 95%CI: 1.16-1.61; P < 0.01). DM was significantly associated with AF in both unadjusted (OR = 2.02; 95%CI: 1.14-3.58; P = 0.04) and adjusted analyses (adjusted OR = 2.68; 95%CI: 1.68-4.27; P = 0.01). The Joanna Briggs Institute tool revealed a low risk of bias. Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis, performed by sequentially excluding each study, demonstrated no significant change in the overall effect estimates, indicating the robustness and stability of our results.

DM significantly increased the risk of ACM and AF, highlighting the importance of tighter glycemic control and cardiovascular risk factor modification among patients with HCM.

Core Tip: This meta-analysis evaluated the impact of diabetes mellitus (DM) on clinical outcomes in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), focusing on all-cause mortality and atrial fibrillation. The findings underscore the importance of recognizing DM as a modifier of adverse outcomes in HCM, particularly due to its contribution to arrhythmias and cardiac dysfunction. The included studies had a low risk of bias, and sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of the results. Clinicians should consider more aggressive glycemic and cardiovascular risk factor control in HCM patients with comorbid diabetes to reduce preventable complications and improve long-term outcomes. This study fills a crucial gap in evidence linking DM to poor prognosis in HCM.

- Citation: Damarlapally N, Vempati R, Doshi KM, Singh M, Prajapati K, Modi D, Singh P, Desai R. Impact of diabetes mellitus on mortality and atrial fibrillation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Diabetes 2025; 16(12): 110494

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v16/i12/110494.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v16.i12.110494

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a genetically inherited myocardial disorder characterized predominantly by thickening of the left ventricle, especially of the interventricular septum, in the absence of another cardiac, systemic, or metabolic disease[1]. The thickening leads to impaired ventricular relaxation, elevated diastolic pressures, and, in some cases, obstruction of the left ventricular outflow tract. These abnormalities lead to numerous adverse outcomes, such as sudden cardiac death (SCD), heart failure (HF), and atrial fibrillation (AF)[2]. The prevalence of HCM is estimated to be around 1 in 500 by most data; however, the actual burden is most likely much higher, considering the number of cases that go unrecognized in the general population, highlighting its importance in clinical practice and public healthcare[3]. It is a common genetic heart disease reported globally and caused by more than 1400 mutations in 11 or more genes[4]. These genetic changes in the sarcomere proteins lead to atypical hypertrophy of the cardiac myocytes, which sub

Given the well-established risk profile, pre-existing genetic conditions such as HCM can independently impair cardiac function and result in worse clinical outcomes[7,8]. Diabetic cardiomyopathy refers to the structural and functional changes in the myocardium specifically due to diabetes, independent of hypertension or CAD[9]. The major pa

The precise mechanism through which DM may impact cardiovascular outcomes in HCM remains unclear. Considering the challenging course of management of HCM as well as the worldwide prevalence of DM, this systematic review and meta-analysis primarily aims to provide a detailed insight to evaluate symptom severity, the progression of HF, the incidence of arrhythmias, hospitalization rates, and mortality among diabetic patients with HCM. It also helps assess the relationship between DM and specific complications like myocardial fibrosis, left ventricular outflow obstruction, or the need for invasive treatments like septal myectomy or alcohol septal ablation by compiling and comprehending the results from various available studies. This research may enhance the quality of patient care and decision-making in clinical practice by determining the role of DM in HCM outcomes.

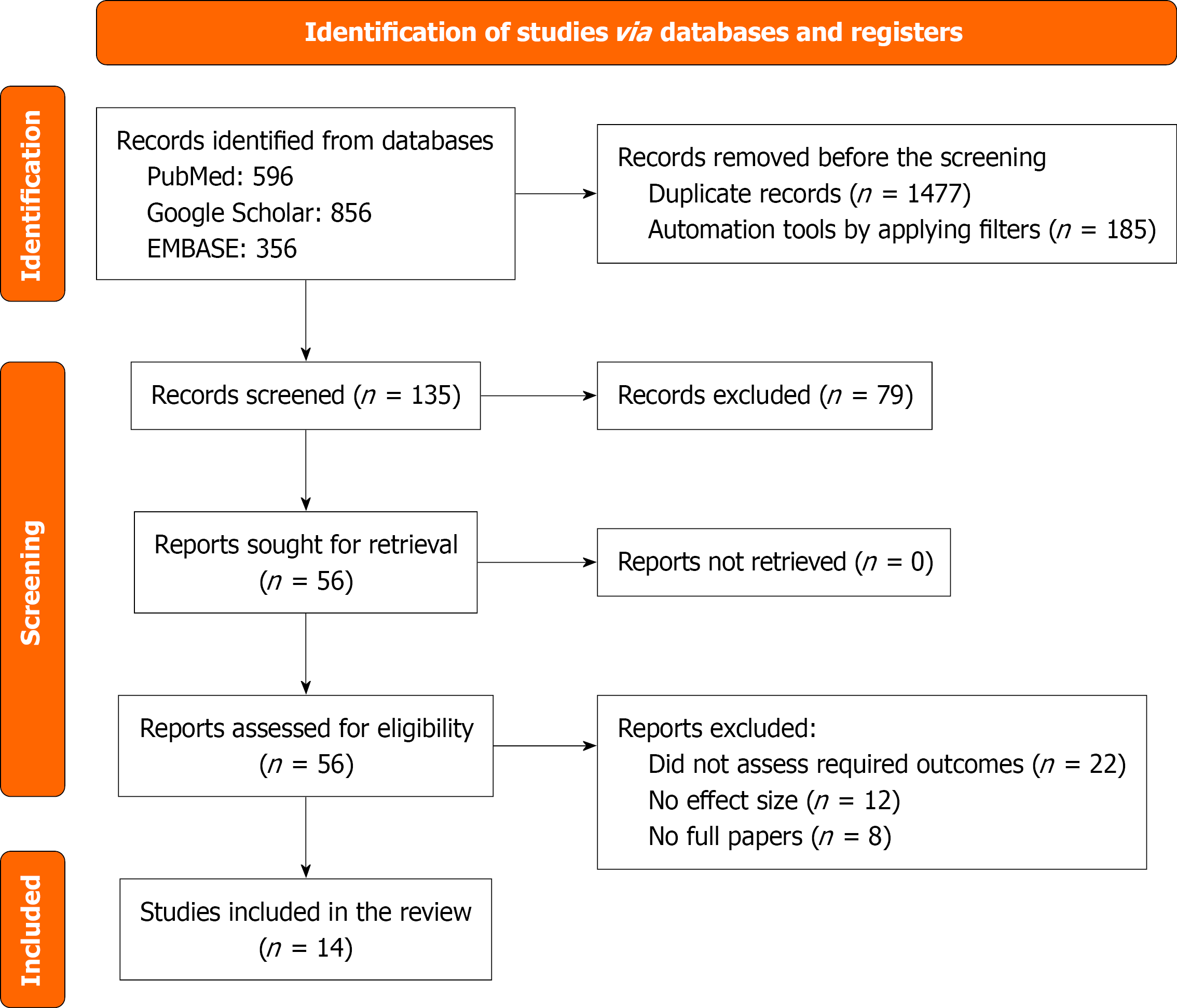

PRISMA guidelines were followed thoroughly for our study[11]. We aim to find the association of DM with ACM and the risk of AF in HCM patients (Figure 1).

We systematically searched for databases such as PubMed, Google Scholar, Scopus, and EMBASE from January 2000 to December 2024 to check for any studies showing the influence of DM on cardiovascular outcomes such as ACM or cardiovascular mortality in patients with HCM. Medical Subject Head terms used were “Diabetes Mellitus”, “Hy

We included observational cohort studies (10 retrospective and 4 prospective) from peer-reviewed journals that contained HCM patients exposed to DM and reported at least one of the outcomes, such as ACM, CVD, SCD, AF, HF, or any coronary events. Studies that did not contain sufficient data or those with incomplete data on outcomes (no effect size, confidence intervals (CIs), or P values), non-original studies such as case reports, reviews, letters to editors, non-English studies, or those without a clear definition of DM status were excluded. Those articles that met our eligibility criteria were also checked for the availability of full text.

After a thorough search of the articles from various peer-reviewed databases, two reviewers, independently screened selected studies through their titles and abstracts using the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria to yield 14 final studies. Data extraction was performed by six co-authors and later independently reviewed by two reviewers. The extracted data included the study design, sample size, patient demographic characteristics [age, sex, body mass index (BMI), labs, and comorbidities], and outcomes (ACM, CVD, AF, SCD, stroke, HF, or any cardiovascular-related outcome). Any dissimilarities were resolved through consensus or consultation with the third reviewer, throughout the selection process (Table 1).

| Ref. | Study type | Country | Duration in years | Sample size | Age in years | Males | BMI in kg/m2 | HTN | Dyslipidemia | Syncope | AF | DM | CAD | BB | CCB |

| Hajouli et al[13], 2024 | R | United States | 5 | 80502 | 63 ± 20 | 38954 (48.39) | 30.6 ± 9.4 | 59241 (73.6) | NA | 10384 (12.9) | 14973 (18.6) | NA | 22637 (28.1) | 44944 (55.8) | NA |

| Wang et al[14], 2024 | R | China | 7 | 225 | 49.5 ± 13.6 | 119 (52.9) | 25.7 ± 4.3 | 82 (36.4) | 43 (19.1) | 22 (9.7) | 35 (15.5) | NA | NA | 149 (66.2) | 14 (6.2) |

| Lin et al[15], 2023 | R | China | 15 | 98 | 58.7 ± 16.5 | 82 (83.7) | 26.3 ± 5.5 | 39 (39.7) | 28 (28.5) | NA | NA | 24 (24.5) | 20 (20.4) | NA | NA |

| Lee et al[16], 2022 | R | Korea | 6 | 9883 | 58.5 ± 13.1a | 7085 (71.7)a | N/A | 5493 (55.6) | 4158 (42.1) | NA | 1119 (11.3) | 1327 (13.4) | 264 (2.7) | NA | NA |

| Sridharan et al[17], 2022 | P | United States | 4 | 2269 | 54 ± 15 | 1392 (61) | 30 ± 3.4 | 613 (27) | 885 (39) | 227 (10) | 454 (20) | 250 (11) | 181 (8) | N/A | N/A |

| Cui et al[18], 2022 | R | United States | 21 | 3859 | 54.8 ± 3.4 | 2115 (54.8) | 28.6 ± 2 | 1764 (45.7)a | NA | NA | 556 (14.4) | 357 (9.2)a | 454 (11.7)a | 3054 (79.1)a | 1398 (36.2)a |

| Hsu et al[19], 2020 | R | Taiwan | 7 | 598 | 66.3 ± 13.0 | 262 (43.8) | NA | 347 (58) | 132 (22.1) | NA | NA | 145 (24.2) | 276 (46.2) | 196 (32.8) | 197 (32.9) |

| Raphael et al[20], 2020 | P | United Kingdom | 10 | 348 | 62 ± 14a | 254 (73) | NA | 125 (36) | 821 (23) | NA | NA | 39 (11) | 47 (14) | 188 (54)a | 54 (16) |

| Rozen et al[21], 2020 | R | United States | 13 | 1885 | 62 ± 3.7a | 832 (53.2)a | NA | 1036 (55.5) | NA | NA | NA | 288 (15.3) | NA | NA | NA |

| Meghji et al[22], 2019 | R | United States | 55 | 2506 | 55.6 ± 3.9 | 1379 (55) | 29.65 ± 2.1 | 1238 (49.4)a | 1539 (61.4) | 471 (18.8) | 486 (19.4) | 231 (9.2) | NA | 1997 (79.7) | 953 (38) |

| Nguyen et al[23], 2019 | R | United States | 56 | 2913 | 60.4 ± 2.7 | 2913 (54.9) | 29.6 ± 1.8 | 1454 (49.9) | 1784 (61.2) | NA | NA | 284 (9.7) | NA | NA | NA |

| Li et al[24], 2019 | R | China | 13 | 319 | 48.2 ± 14.3 | 120 (54) | N/A | 47 (21) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3 (1.34) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Jensen et al[25], 2011 | P | Denmark | 2 | 279 | 59 ± 14 | 150 (54) | NA | 123 (44) | NA | NA | NA | 19 (7) | NA | NA | NA |

| Moon et al[26], 2011 | P | Korea | 6 | 454 | 61 ± 11 | 316 (70)a | NA | 232 (51)a | NA | 5 (1) | NA | 69 (15)a | NA | 142 (31) | 118 (26) |

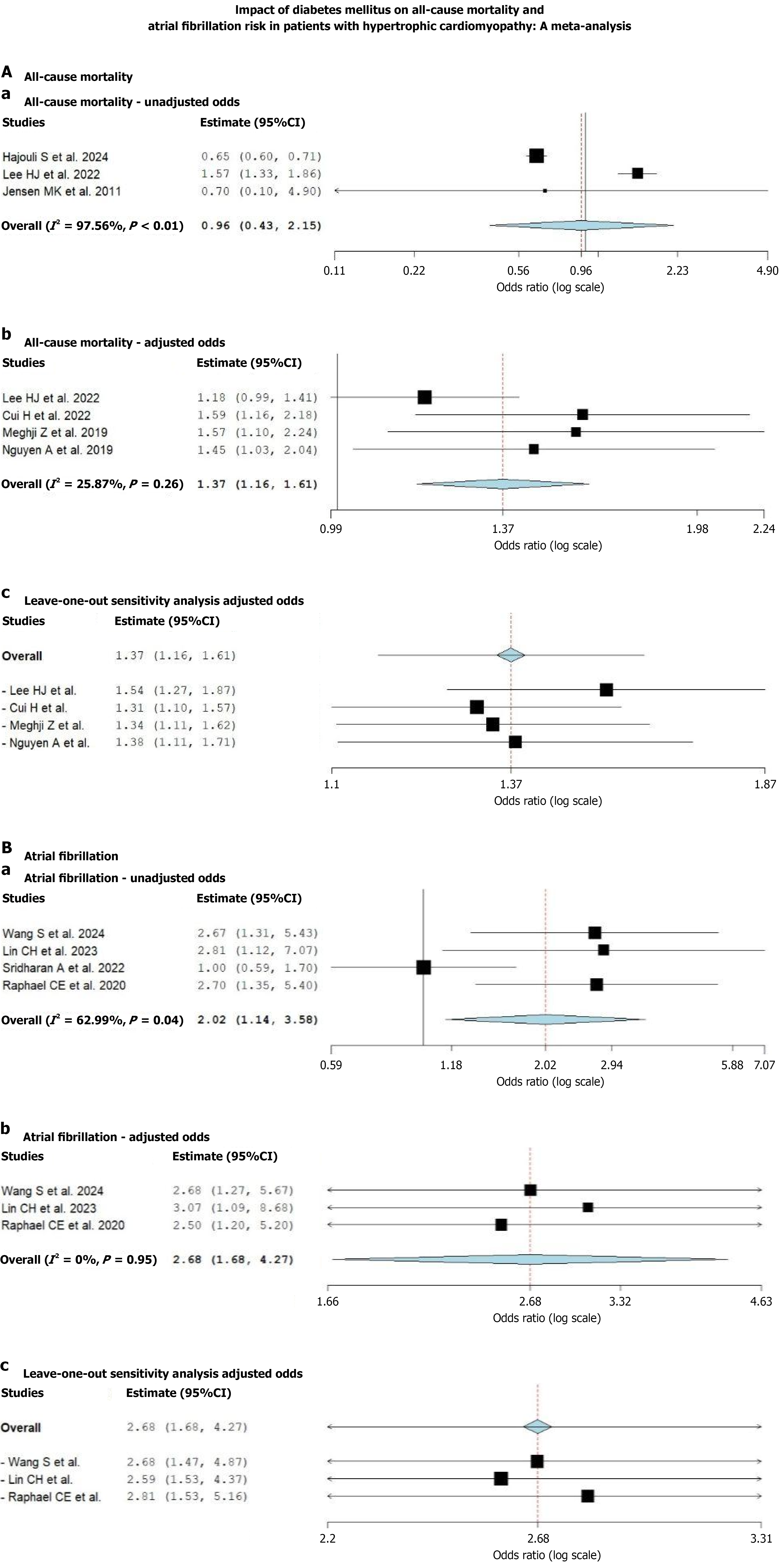

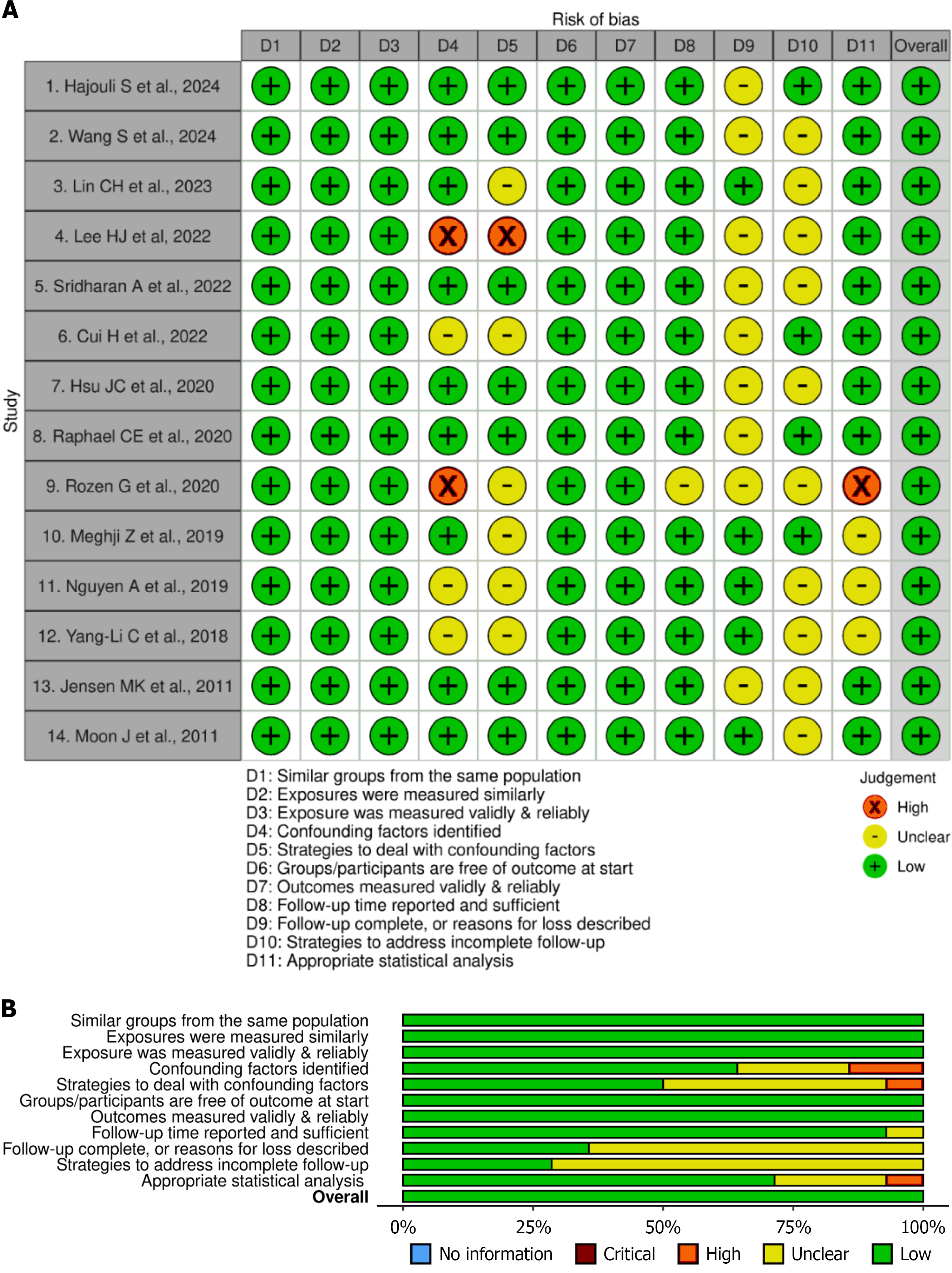

The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) tool was used for qualitative assessment of the selected 14 cohort studies based on 11 questions. The key domains tested in the tool were the appropriateness of the sample selection and study design, compatibility of the groups selected, management of confounding factors, and validity of the outcomes measured. Based on the quality ratings of the 11 questions evaluated in each included study, they were categorized as low (“no” on most responses), moderate (“yes”, “unclear”, and a few “no” responses), or high (“yes” on most responses) quality studies. The risk of bias visualization tool was used to visually summarize the risk of bias for all the included studies. These were presented using traffic light and summary plots, derived from the JBI quality appraisal tool[12]. Using this tool, the “yes”, “no”, and “unclear” responses for individual studies were marked in green, red, and yellow, respectively. Additionally, the overall result of each study was marked as green, red, or yellow if the cumulative quality of the study was high, low, or unclear, respectively. Leave-one-out study sensitivity analysis was carried out to determine the effect of individual studies on the overall results (Figure 2). Publication bias was assessed through funnel plots and the symmetrical distribution of the plots and the Doi plot (LFK index). There was no asymmetry for ACM, whereas minor asymmetry was observed for AF outcomes (Supplementary Figure 1).

Data extraction and meta-analysis were conducted using 10 selected studies through Microsoft Excel, and data synthesis was done using OpenMeta (Analyst)[13-26]. Random-effect models were used to calculate pooled effect sizes, such as OR (adjusted and unadjusted) with a 95%CI. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Forest plots were generated using the ORs. The I2 statistic was used to test heterogeneity, and a leave-one-out study sensitivity analysis was done to check for the robustness of the included studies. Only ten studies[13-18,20,22,23,25] with a total sample size of 102882 were subjected to meta-analysis. The limitation resulted from the non-availability of the effect sizes of the outcomes for the remainder of the four studies[19,21,24,26]. All 14 studies were subjected to a systematic review.

A total of 14 studies published from 2011 to 2024 were selected for our systematic review and meta-analysis, comprising 106138 patients with HCM. From the available data, 17998 were diabetic, and the mean age of the entire study population was 61.76 ± 19.84 years, with 61.55% males. 10 studies were retrospective[13-16,18,19,21-24], and 4 studies were of prospective cohort studies[17,20,25,26] design. The study population (> 50%) was primarily from the United States, China, and Korea. Many participants had comorbidities such as diabetes (reported in all 14 studies), hypertension (14 studies), dyslipidemia (8 studies), CAD (7 studies), and syncope (4 studies), and medications like beta-blockers (7 studies) and calcium channel blockers (6 studies) were used. BMI of the participants ranged from a mean value of 26.3 ± 5.5 kg/m2 to 30.6 ± 9.4 kg/m2. AF was reported among 6 studies[13,14,16,17,18,22] as the baseline characteristic. A detailed synopsis of the baseline characteristics of the included studies among the study population can be seen in Table 1.

Out of the selected 14 studies, 10 studies were included in the meta-analysis, as others did not have sufficient data (Figure 1). All 14 studies were subjected to a systematic review. We aimed to find the association of ACM and AF with HCM among patients with DM.

ACM: In the systematically analyzed 14 studies, six studies[13,16,18,22,23,25] reported ACM, and the impact of diabetes was mixed. Elderly patients (≥ 60 years) and those having a higher rate of hypertension (> 70%) were linked to a heightened risk of mortality from all causes. Research involving younger groups and reduced hypertension prevalence (< 40%) indicated decreased mortality rates. Four studies[16,18,22,23] reported only adjusted OR (aOR); two studies[16,25] reported only unadjusted OR, and one study[16] reported both aOR and unadjusted OR with respect to ACM outcome. Four studies revealed that the pooled aOR for ACM in DM patients with HCM was 1.37 (95%CI: 1.16-1.61, P < 0.01) compared to non-diabetic patients, signifying a 37% increased risk of mortality in diabetic patients with HCM. The results were statistically significant with a mild I2 of 25.87%. However, the pooled unadjusted OR for ACM in the HCM patients showed a non-significant association of 0.96 (95%CI: 0.43-2.15, P = 0.93) among 3 studies with a severe I2 of 97.56%, indicating a high heterogeneity. This heterogeneity could be due to the effect of factors such as age or hypertension (Figure 2).

AF: Of the 14 studies, four studies[14,15,17,20] reported AF as a new or recurrent outcome, and diabetes was shown to be uniformly linked to a higher risk of AF in individuals with HCM. Research indicated that a higher baseline BMI (> 30 kg/m2) and elevated hypertension rates were found to have an increased AF occurrence (approximately 13% compared to approximately 10% in lower-risk cohorts). One study reported unadjusted OR only[17]; three studies[14,15,20] reported both aOR and OR with respect to AF outcome. Three studies revealed that the pooled aOR for AF in DM patients with HCM was 2.68 (95%CI: 1.68-4.27, P < 0.01) compared to non-diabetic patients, signifying a 168% increased risk of AF in diabetic patients with HCM. The results were statistically significant, with an I2 of 0% indicating no heterogeneity among the studies (Figure 2). Also, four studies[14,15,17,20] revealed that the pooled unadjusted OR for AF in DM patients with HCM was 2.02 (95%CI: 1.14-3.58, P = 0.04) compared to non-diabetic patients, signifying a 102% increased risk of mortality in diabetic patients with HCM. The results were statistically significant with a moderate I2 of 62.99% (Figure 2).

Among our 14 included studies, only two studies[13,16] reported HF association (an adjusted HR of 1.46, 95%CI: 1.28-1.67; OR = 0.75, 95%CI: 0.69-0.81, respectively); one study[14] documented supraventricular tachycardia (SVT, aOR = 1.9, 95%CI: 1.01-3.58) and non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT) associations (aOR = 2.18, 95%CI: 1.04-4.57), suggesting a probable lower prevalence of HF or tachycardia in the HCM study population compared to ACM and AF. We couldn’t find any other predominant cardiovascular outcomes other than those mentioned above. Multicentric studies with larger populations are needed to be employed to substantiate and acknowledge any other cardiovascular outcomes.

Although SCD is an established complication of HCM, particularly in the young age group, limited data are available on the correlation between SCD and DM in this group. Of the studies reviewed, only one[27] specifically mentioned the outcome of SCD with diabetes. Wang et al[27] noted that type 2 DM and HCM patients undergoing septal myectomy had significantly increased SCD occurrence in comparison with non-diabetic patients (4.5% vs 0.0%, P = 0.04).

The leave-one-out sensitivity analyses presented in Figure 2 evaluate the robustness of the pooled adjusted ORs for ACM and AF, respectively, by iteratively removing one study at a time. For ACM, exclusion of each study individually resulted in consistently significant ORs ranging from 1.31 to 1.54, with all CIs remaining above 1.0. This suggests that no single study disproportionately influenced the pooled effect estimate (overall OR: 1.37, 95%CI: 1.16-1.61), confirming the stability of the association between DM and increased ACM in HCM. Similarly, in the AF analysis, sequential exclusion of included studies showed minimal impact on the overall result (OR = 2.68, 95%CI: 1.68-4.27), with point estimates remaining stable (ranging from 2.59 to 2.81), further confirming the robustness of the association between diabetes and heightened AF risk in HCM patients.

The risk of bias was estimated through the JBI tool, which concluded that 12 of the selected studies were of high quality, with most of the question responses being yes, and 2 selected studies were of moderate quality. Two studies[16,21] of moderate quality could not identify confounding factors and their strategies to tackle them. Most of the studies did not mention whether the follow-up was complete or incomplete and their respective plan to deal with them (Figure 3). Nevertheless, all the included studies were of high quality and shown as green in the risk of bias visualization tool. Funnel plots and Doi plots were generated for both outcomes despite subgroup sizes < 5. Visual inspection did not suggest marked asymmetry. The LFK index was 0.96 for ACM (no asymmetry) and 1.14 for AF (minor asymmetry), supporting the absence of significant publication bias (Supplementary Figure 1).

This large meta-analysis evaluated that DM is associated with a 168% increased risk of AF and a 37% increased risk of ACM. HCM, a genetic cardiac disorder marked by left ventricular hypertrophy, often leads to diastolic dysfunction, myocardial ischemia, and various arrhythmias[13,14]. Clinically, HCM manifests across a wide spectrum, from asymptomatic states to progressive HF and SCD[13,14]. On the other hand, DM is a well-established risk factor for multiple CVDs, with mechanisms that include hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress, inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction. These changes promote myocardial fibrosis and adverse remodeling, which may amplify the clinical burden of HCM[14,16].

Our findings align with the existing literature. DM was an independent risk factor for AF, SVT, and NSVT among patients with obstructive HCM[14]. The intersection of HCM and DM presents a pathophysiologically synergistic scenario. Multiple studies suggest that DM exacerbates arrhythmogenic risk in HCM through atrial structural remodeling, myocardial fibrosis, and left atrium dilation, contributing to a higher burden of AF and increased recurrence following catheter ablation[13,14,15,20,21]. The increased left atrial volume and the extent of ventricular late gadolinium enhancement were independently associated with AF risk in HCM patients with DM, conveying the mechanistic link between them[20]. In addition, the pro-arrhythmic burden conferred by DM also has its impact on procedural safety and outcomes, as DM was found to be a strong independent predictor of procedural complications following AF ablation in patients with HCM[21].

The evidence on the ACM was contradictory among the included studies. Hajouli et al[13] found the risk of ACM (OR = 0.654, 95%CI: 0.608-0.705) and new-onset HF (OR = 0.75, 95%CI: 0.69-0.81) among HCM patients with DM (cohort 2, comparator group), compared to those without DM (cohort 1, reference group), after adjustment for major confounders. On the other hand, data from the Korean National Health Insurance Service cohort demonstrated a 15% increase in HF incidence among diabetic HCM patients after propensity matching, though an association with ACM was observed only in unmatched populations. Notably, this study could not adjust for glycated hemoglobin levels, ejection fraction, or the degree of hypertrophy, leaving room for residual confounding[16]. In a study by Cui et al[18], DM was found to independently predict ACM in patients undergoing septal reduction therapy (alcohol septal ablation or surgical myectomy). Lee et al[16], however, reported only a borderline association between DM and ACM (adjusted HR = 1.18; 95%CI: 0.99-1.41), which lost statistical significance after adjusting for comorbidities[11]. These varying results are likely due to the differences in cohort characteristics, DM duration and severity, and the extent of metabolic control. Collectively, existing literature and our study align with the premise that DM worsens atrial and ventricular remodeling in HCM, contributing to an increased incidence of AF and ACM.

Furthermore, the impact of DM on outcomes following septal reduction therapy has been explored with contrasting conclusions in the literature, but it was widely found to be associated with poor outcomes. Wang et al[27] found that patients with HCM and type 2 DM had a significantly higher rate of SCD after myectomy (4.5% vs 0.0%, P = 0.04). In contrast, Wasserstrum et al[28] reported no difference in SCD risk, though patients with DM had worse functional capacity and more advanced HF symptoms. Interestingly, predicted 3-year survival free from cardiovascular death was similar across DM and non-DM groups, but the SCD-free survival paradoxically appeared lower among non-DM patients, likely reflecting selection or survival bias in surgical cohorts[27]. However, the impact of DM on SCD or cardiovascular mortality among patients with HCM remains unclear and may be confounded by comorbidities or differing thresholds for intervention.

At the molecular level, several mechanisms explain how DM may promote arrhythmogenesis in HCM. Autonomic dysfunction, insulin resistance, and myocardial remodeling, hallmarks of diabetic cardiomyopathy, can promote electrical instability. Microvascular dysfunction and disrupted myocardial fiber orientation may delay conduction and increase automaticity[29-31]. Furthermore, increased oxidative stress and elevated norepinephrine levels have been implicated in cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and calcium overload[32,33]. Insulin resistance has been shown to elevate microRNA-29 expression, promoting fibrosis, while coexisting conditions like hypertension, CAD, and obstructive sleep apnea may amplify arrhythmic risk[14,34]. The structural changes in the myocardium and atria play a key role in the pa

| Mechanism | Explanation | Associated outcome(s) | Supporting evidence with references |

| Myocardial fibrosis | Chronic hyperglycemia and insulin resistance promote myocardial and atrial collagen deposition. This stiffens the myocardium and disrupts conduction | AF, ACM | Fibrosis contributes to arrhythmogenic substrate and diastolic dysfunction, increasing AF risk and overall mortality[13,14,29,34,37] |

| Atrial remodeling and LA dilation | Elevated LV filling pressures and impaired diastolic function lead to left atrial enlargement and structural remodeling | AF | LA dilation facilitates reentry circuits and AF development in HCM patients with DM[14,20,36] |

| Microvascular dysfunction | DM causes capillary rarefaction and endothelial dysfunction, reducing perfusion and increasing ischemia risk | ACM | Ischemia and oxygen mismatch promote myocardial injury, fibrosis, and adverse outcomes[14,29,30] |

| Autonomic imbalance | DM leads to sympathetic overactivity and reduced vagal tone, predisposing to electrical instability | AF, SVT, NSVT | Increased sympathetic tone and reduced HR variability raise arrhythmia susceptibility[14,31] |

| Oxidative stress and inflammation | Hyperglycemia generates ROS and pro-inflammatory cytokines that damage cardiomyocytes | AF, ACM | Oxidative stress leads to apoptosis, impaired function, and fibrotic remodeling[32,33,39] |

| Disrupted calcium handling | ROS activates CaMKII, resulting in abnormal calcium influx and delayed afterdepolarizations | AF, VT, NSVT | Calcium overload causes ectopic activity and proarrhythmic conditions[32] |

| Elevated microRNA-29 expression | Insulin resistance induces microRNA-29, which stimulates myocardial hypertrophy and fibrosis | AF, ACM | microRNA-29a is a profibrotic biomarker found elevated in HCM and DM[34] |

| Structural remodeling | Combined effects of HCM and DM cause exaggerated hypertrophy, LV wall thickness, and chamber dilation | AF, ACM | Reflects a more advanced phenotype with increased mortality and arrhythmic burden[14,20,30] |

| Proarrhythmic medication patterns | High beta-blocker used in patients developing AF suggests suboptimal rhythm control despite standard therapy | AF | Patients with AF had higher baseline beta-blocker use than those in sinus rhythm, questioning its protective role[20] |

| Comorbidities (HTN, OSA, CAD) | These amplify myocardial stress, systemic inflammation, and fibrosis when combined with DM | AF, ACM | Hypertension, CAD, and sleep apnea synergistically raise cardiovascular risk in HCM-DM populations[14,16,34] |

Additional studies have evaluated whether DM worsens the overall prognosis in HCM beyond arrhythmic endpoints. Although individuals with both conditions had worse survival, there were no significant differences in SCD or HCM-specific endpoints such as transplant rates[28]. Increased mortality among diabetic HCM patients was also found to be driven by non-cardiovascular causes[16]. Other studies supported these observations, which showed that DM conferred excess risk for cardiovascular and ACM, broadly mediated by systemic inflammation and metabolic dysregulation[39].

Our systematic review and meta-analysis were done with a comprehensive and rigorous methodology by following PRISMA guidelines, ensuring transparency and methodological rigor in data selection and analysis. Our study has included 106138 patients with HCM across multiple studies, enhancing the statistical power of our findings. By pooling both unadjusted and aORs, our study findings are reliable by mitigating the impact of confounding variables, although not completely. Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis confirmed that our study findings are robust without concerns about the impact of individual studies on the overall conclusions. Quality assessment of the included studies using the JBI tool demonstrated that all of the included studies were of high quality. The inclusion of both prospective and retrospective studies will introduce the variability in study methodology and data collection. Our study does not include subgroup analysis for factors such as glycemic control (glycated hemoglobin levels), insulin use, and the duration of diabetes, due to inconsistent or unavailable reporting of glycemic metrics across the studies included. Even though aORs were pooled, residual confounding due to various factors, such as lifestyle factors and genetic predisposition, could not be fully accounted for. Our study does not distinguish between obstructive and non-obstructive HCM subtypes, which may have different natural courses. The limited geographic and ethnic diversity of the studies we reviewed may impact the generalizability of our findings. Variations in race, genetic predisposition, and access to healthcare could influence outcomes for patients with HCM and DM. Despite these limitations, our study highlights the importance of early recognition and treatment of DM in patients diagnosed with HCM. Although funnel plot interpretation is limited due to small subgroup sizes, Doi plot analysis with LFK indices (0.96 for ACM and 1.14 for AF) indicated no or minor asymmetry. Still, due to low study counts, the possibility of undetected publication bias cannot be fully excluded.

Stringent glycemic control and cardiovascular risk factor modification should be prioritized among diabetic HCM patients. Early anticoagulation therapy should be considered for those with thromboembolic risks. Research on genetic mutations associated with HCM and DM-related metabolic reactions can provide valuable insights into pathophysiology. Evaluate demographic disparities in the outcomes and assess specific diabetic treatments, such as metformin and glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists, in the diabetic HCM patients. Studies must stratify between obstructive vs non-obstructive HCM subtypes and genetic vs non-genetic presentations to acknowledge the influence of outcomes within each subtype. Advanced imaging modalities such as cardiac magnetic resonance imaging with late gadolinium enhancement and advanced biomarkers can be utilized to identify the myocardial changes and predict adverse outcomes at an early stage.

Our pooled adjusted analysis revealed that DM was associated with a 168% increase in the odds of AF and a 37% increase in the odds of all-cause mortality. Optimizing blood sugar control, monitoring for subclinical arrhythmias, and considering anticoagulation when clinically indicated may help reduce arrhythmic burden and potentially improve outcomes in this high-risk population. Future research should focus on the effects of glycemic control and specific anti-diabetic medications on cardiac health, emphasizing the need for a multidisciplinary approach to improve outcomes among HCM patients with DM.

| 1. | Ommen SR, Mital S, Burke MA, Day SM, Deswal A, Elliott P, Evanovich LL, Hung J, Joglar JA, Kantor P, Kimmelstiel C, Kittleson M, Link MS, Maron MS, Martinez MW, Miyake CY, Schaff HV, Semsarian C, Sorajja P. 2020 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2020;142:e558-e631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Article Influence: 40.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Maron BJ, Maron MS. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2013;381:242-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 778] [Cited by in RCA: 904] [Article Influence: 69.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Semsarian C, Ingles J, Maron MS, Maron BJ. New perspectives on the prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:1249-1254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 633] [Cited by in RCA: 1023] [Article Influence: 93.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kubo T, Gimeno JR, Bahl A, Steffensen U, Steffensen M, Osman E, Thaman R, Mogensen J, Elliott PM, Doi Y, McKenna WJ. Prevalence, clinical significance, and genetic basis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with restrictive phenotype. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2419-2426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cosentino F, Grant PJ, Aboyans V, Bailey CJ, Ceriello A, Delgado V, Federici M, Filippatos G, Grobbee DE, Hansen TB, Huikuri HV, Johansson I, Jüni P, Lettino M, Marx N, Mellbin LG, Östgren CJ, Rocca B, Roffi M, Sattar N, Seferović PM, Sousa-Uva M, Valensi P, Wheeler DC; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2019 ESC Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:255-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1670] [Cited by in RCA: 2765] [Article Influence: 553.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Matheus AS, Tannus LR, Cobas RA, Palma CC, Negrato CA, Gomes MB. Impact of diabetes on cardiovascular disease: an update. Int J Hypertens. 2013;2013:653789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 264] [Cited by in RCA: 328] [Article Influence: 25.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Badran HM, Helmy JA, Ahmed NF, Yacoub M. Impact of Diabetes Mellitus on Left Ventricular Mechanics and Long-Term Outcome in Patients with Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Echocardiography. 2024;41:e70048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lopes LR, Losi MA, Sheikh N, Laroche C, Charron P, Gimeno J, Kaski JP, Maggioni AP, Tavazzi L, Arbustini E, Brito D, Celutkiene J, Hagege A, Linhart A, Mogensen J, Garcia-Pinilla JM, Ripoll-Vera T, Seggewiss H, Villacorta E, Caforio A, Elliott PM; Cardiomyopathy Registry Investigators Group. Association between common cardiovascular risk factors and clinical phenotype in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) EurObservational Research Programme (EORP) Cardiomyopathy/Myocarditis registry. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2022;9:42-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wu H, Norton V, Cui K, Zhu B, Bhattacharjee S, Lu YW, Wang B, Shan D, Wong S, Dong Y, Chan SL, Cowan D, Xu J, Bielenberg DR, Zhou C, Chen H. Diabetes and Its Cardiovascular Complications: Comprehensive Network and Systematic Analyses. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:841928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mekhaimar M, Al Mohannadi M, Dargham S, Al Suwaidi J, Jneid H, Abi Khalil C. Diabetes outcomes in heart failure patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Front Physiol. 2022;13:976315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44932] [Cited by in RCA: 50877] [Article Influence: 10175.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 12. | McGuinness LA, Higgins JPT. Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis): An R package and Shiny web app for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Res Synth Methods. 2021;12:55-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 613] [Cited by in RCA: 3237] [Article Influence: 539.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hajouli S, Belcher A, Annie F, Elashery A. Is Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus an Independent Risk Factor for Mortality in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy? Cardiol Res. 2024;15:198-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wang S, Zhang K, He M, Guo H, Cui H, Wang S, Lai Y. Effect of type 2 diabetes on cardiac arrhythmias in patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2024;18:102992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lin CH, Lin CY, Chung FP, Lin YJ, Chang SL, Lo LW, Hu YF, Chao TF, Liao JN, Chang TY, Tuan TC, Kuo L, Wu CI, Liu CM, Liu SH, Li GY, Kuo MJ, Weng CJ, Chen SA. Catheter ablation in Asian patients with atrial fibrillation and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: electrophysiological characteristics of recurrence and long-term clinical outcomes. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023;10:1135230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lee HJ, Kim HK, Kim BS, Han KD, Rhee TM, Park JB, Lee H, Lee SP, Kim YJ. Impact of diabetes mellitus on the outcomes of subjects with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A nationwide cohort study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;186:109838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sridharan A, Maron MS, Carrick RT, Madias CA, Huang D, Cooper C, Drummond J, Maron BJ, Rowin EJ. Impact of comorbidities on atrial fibrillation and sudden cardiac death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2022;33:20-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cui H, Schaff HV, Wang S, Lahr BD, Rowin EJ, Rastegar H, Hu S, Eleid MF, Dearani JA, Kimmelstiel C, Maron BJ, Nishimura RA, Ommen SR, Maron MS. Survival Following Alcohol Septal Ablation or Septal Myectomy for Patients With Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:1647-1655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hsu JC, Huang YT, Lin LY. Stroke risk in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients with atrial fibrillation: a nationwide database study. Aging (Albany NY). 2020;12:24219-24227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Raphael CE, Liew AC, Mitchell F, Kanaganayagam GS, Di Pietro E, Newsome S, Owen R, Gregson J, Cooper R, Amin FR, Gatehouse P, Vassiliou V, Ernst S, O'Hanlon R, Frenneaux M, Pennell DJ, Prasad SK. Predictors and Mechanisms of Atrial Fibrillation in Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2020;136:140-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Rozen G, Elbaz-Greener G, Marai I, Andria N, Hosseini SM, Biton Y, Heist EK, Ruskin JN, Gavrilov Y, Carasso S, Ghanim D, Amir O. Utilization and Complications of Catheter Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation in Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e015721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Meghji Z, Nguyen A, Fatima B, Geske JB, Nishimura RA, Ommen SR, Lahr BD, Dearani JA, Schaff HV. Survival Differences in Women and Men After Septal Myectomy for Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4:237-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Nguyen A, Schaff HV, Sedeek AF, Geske JB, Dearani JA, Ommen SR, Lahr BD, Viehman JK, Nishimura RA. Septal Myectomy and Concomitant Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting for Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy and Coronary Artery Disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95:521-525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Li CY, Shi YQ. Retrospective Analysis of Risk Factors for Related Complications of Chemical Ablation on Hypertrophic Obstructive Cardiomyopathy. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019;112:432-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Jensen MK, Almaas VM, Jacobsson L, Hansen PR, Havndrup O, Aakhus S, Svane B, Hansen TF, Køber L, Endresen K, Eriksson MJ, Jørgensen E, Amlie JP, Gadler F, Bundgaard H. Long-term outcome of percutaneous transluminal septal myocardial ablation in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: a Scandinavian multicenter study. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4:256-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Moon J, Shim CY, Ha JW, Cho IJ, Kang MK, Yang WI, Jang Y, Chung N, Cho SY. Clinical and echocardiographic predictors of outcomes in patients with apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2011;108:1614-1619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Wang S, Cui H, Ji K, Song C, Ren C, Guo H, Zhu C, Wang S, Lai Y. Impact of type 2 diabetes mellitus on mid-term mortality for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients who underwent septal myectomy. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2020;19:64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Wasserstrum Y, Barriales-Villa R, Fernández-Fernández X, Adler Y, Lotan D, Peled Y, Klempfner R, Kuperstein R, Shlomo N, Sabbag A, Freimark D, Monserrat L, Arad M. The impact of diabetes mellitus on the clinical phenotype of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:1671-1677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ariga R, Tunnicliffe EM, Manohar SG, Mahmod M, Raman B, Piechnik SK, Francis JM, Robson MD, Neubauer S, Watkins H. Identification of Myocardial Disarray in Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy and Ventricular Arrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:2493-2502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Marian AJ, Braunwald E. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Genetics, Pathogenesis, Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Therapy. Circ Res. 2017;121:749-770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 491] [Cited by in RCA: 1013] [Article Influence: 112.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Rowin EJ, Hausvater A, Link MS, Abt P, Gionfriddo W, Wang W, Rastegar H, Estes NAM, Maron MS, Maron BJ. Clinical Profile and Consequences of Atrial Fibrillation in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2017;136:2420-2436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 23.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wagner S, Ruff HM, Weber SL, Bellmann S, Sowa T, Schulte T, Anderson ME, Grandi E, Bers DM, Backs J, Belardinelli L, Maier LS. Reactive oxygen species-activated Ca/calmodulin kinase IIδ is required for late I(Na) augmentation leading to cellular Na and Ca overload. Circ Res. 2011;108:555-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Byon CH, Heath JM, Chen Y. Redox signaling in cardiovascular pathophysiology: A focus on hydrogen peroxide and vascular smooth muscle cells. Redox Biol. 2016;9:244-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Roncarati R, Viviani Anselmi C, Losi MA, Papa L, Cavarretta E, Da Costa Martins P, Contaldi C, Saccani Jotti G, Franzone A, Galastri L, Latronico MV, Imbriaco M, Esposito G, De Windt L, Betocchi S, Condorelli G. Circulating miR-29a, among other up-regulated microRNAs, is the only biomarker for both hypertrophy and fibrosis in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:920-927. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Greenberg B, Chatterjee K, Parmley WW, Werner JA, Holly AN. The influence of left ventricular filling pressure on atrial contribution to cardiac output. Am Heart J. 1979;98:742-751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 252] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Nattel S, Burstein B, Dobrev D. Atrial remodeling and atrial fibrillation: mechanisms and implications. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2008;1:62-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 702] [Cited by in RCA: 848] [Article Influence: 49.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Burstein B, Nattel S. Atrial fibrosis: mechanisms and clinical relevance in atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:802-809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 828] [Cited by in RCA: 962] [Article Influence: 53.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Sivalokanathan S, Zghaib T, Greenland GV, Vasquez N, Kudchadkar SM, Kontari E, Lu DY, Dolores-Cerna K, van der Geest RJ, Kamel IR, Olgin JE, Abraham TP, Nazarian S, Zimmerman SL, Abraham MR. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Patients With Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation Have a High Burden of Left Atrial Fibrosis by Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2019;5:364-375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Baena-Díez JM, Peñafiel J, Subirana I, Ramos R, Elosua R, Marín-Ibañez A, Guembe MJ, Rigo F, Tormo-Díaz MJ, Moreno-Iribas C, Cabré JJ, Segura A, García-Lareo M, Gómez de la Cámara A, Lapetra J, Quesada M, Marrugat J, Medrano MJ, Berjón J, Frontera G, Gavrila D, Barricarte A, Basora J, García JM, Pavone NC, Lora-Pablos D, Mayoral E, Franch J, Mata M, Castell C, Frances A, Grau M; FRESCO Investigators. Risk of Cause-Specific Death in Individuals With Diabetes: A Competing Risks Analysis. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:1987-1995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 262] [Article Influence: 26.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/