©The Author(s) 2025.

World J Diabetes. Dec 15, 2025; 16(12): 114395

Published online Dec 15, 2025. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v16.i12.114395

Published online Dec 15, 2025. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v16.i12.114395

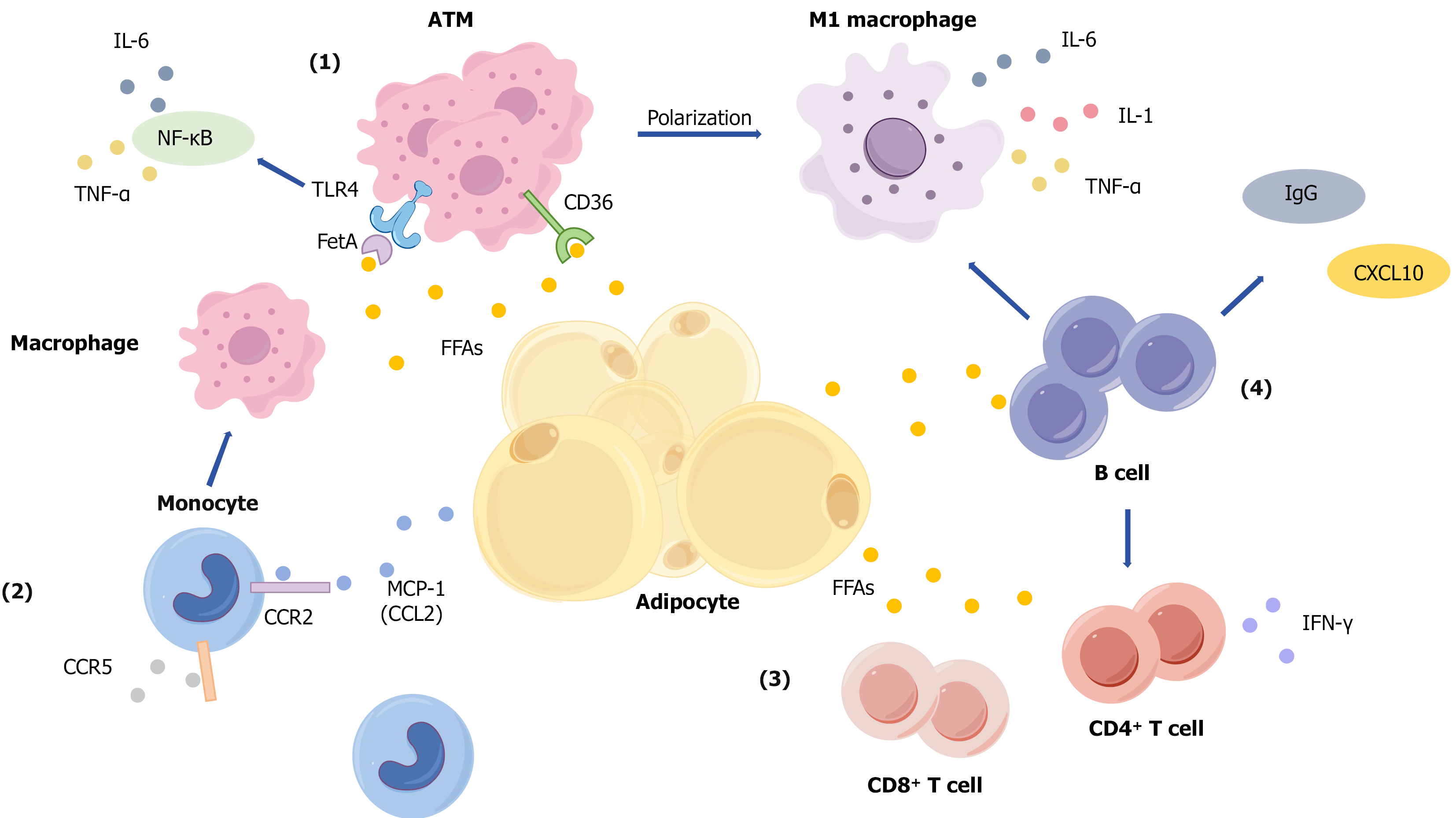

Figure 1 Mechanisms of lipid accumulation-induced adipose tissue immune microenvironment disruption and insulin resistance.

Mechanisms including: (1) Adipocyte hypertrophy and macrophage activation: Hypertrophied adipocytes release excessive free fatty acids (FFAs), which promote macrophage recruitment and differentiation into adipose tissue macrophages. FFAs activate macrophages via receptors such as Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 and cluster of differentiation (CD) 36, driving polarization toward the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype. This leads to the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β, and IL-6. Additionally, fetuin-A binds to TLR4 and indirectly activates the nuclear factor kappa-B signaling pathway, further enhancing TNF-α and IL-6 production. These cytokines collectively impair insulin signal transduction; (2) Monocyte recruitment and infiltration: FFAs and the chemokine monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (CCL2) recruit circulating monocytes to adipose tissue via the CCR2 pathway. Upon infiltration, these monocytes differentiate into macrophages, amplifying the inflammatory response; (3) T cell activation and cytokine secretion: Under the influence of FFAs, both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells become activated and proliferate. They secrete cytokines such as interferon-gamma, which enhance inflammatory responses and promote further macrophage recruitment and activation; and (4) B cell involvement in inflammation: B cells accumulate in adipose tissue, where they contribute to inflammation by activating T cells and secreting pathogenic IgG antibodies and the chemokine CXCL10. These actions exacerbate both local and systemic inflammation, further impairing insulin sensitivity. IL: Interleukin; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor; NF-κB: Nuclear factor kappa-B; TLR: Toll-like receptor; FetA: Fetuin-A; ATM: Adipose tissue macrophage; CD: Cluster of differentiation; FFAs: Free fatty acids; IFN: Interferon; MCP-1: Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1.

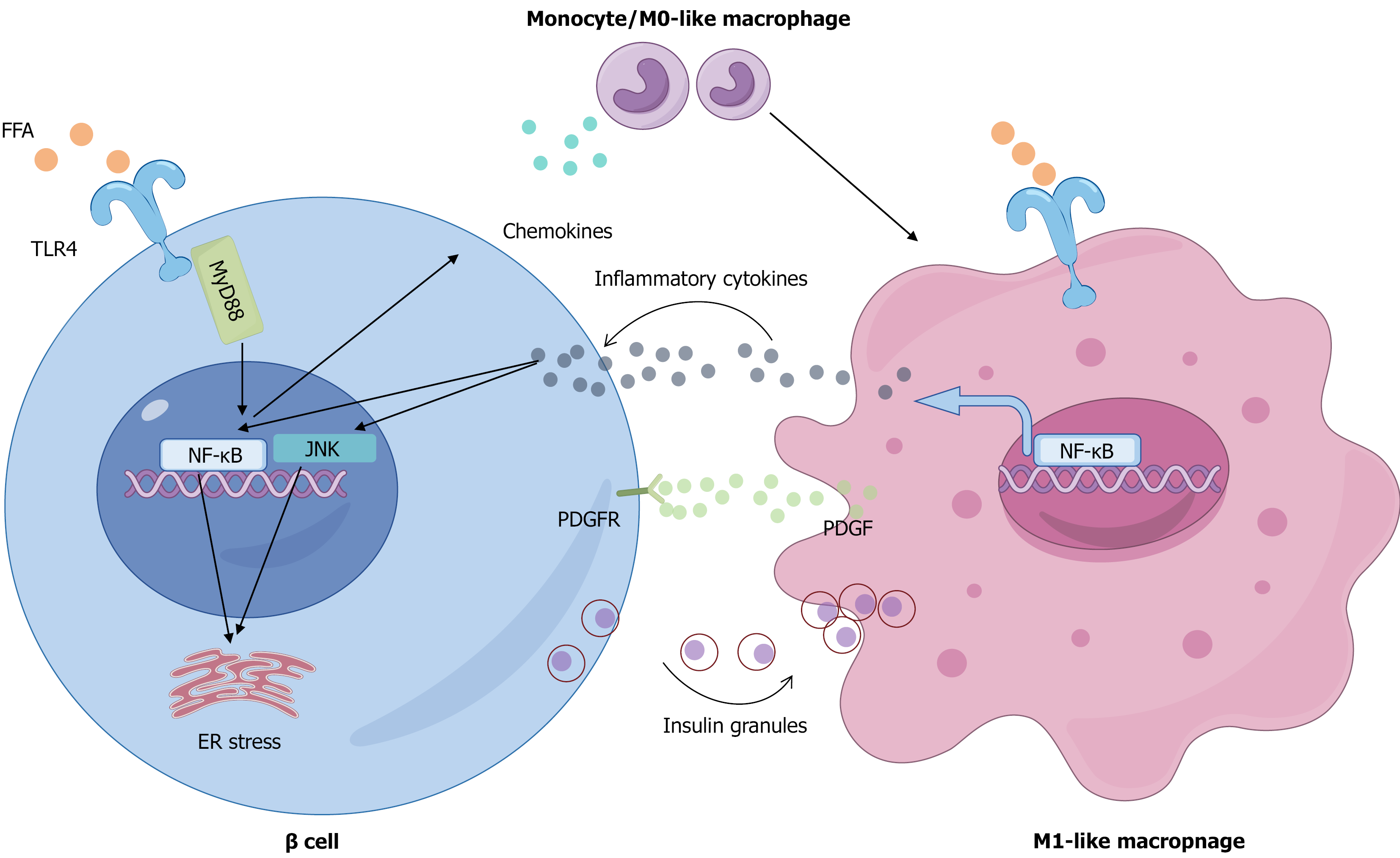

Figure 2 Mechanisms of macrophage-mediated islet inflammation and β-cell dysfunction induced by disordered lipid metabolism.

Elevated circulating free fatty acids initiate islet inflammation by activating the Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4/nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) pathway in pancreatic β-cells, prompting them to secrete chemokines that recruit circulating monocytes. Upon infiltration and under lipotoxic conditions, these monocytes polarize into pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages, which are further activated via the TLR4/NF-κB pathway to secrete abundant inflammatory cytokines. These cytokines in turn impair β-cell function by activating intracellular Janus tyrosine kinase and NF-κB signaling and inducing endoplasmic reticulum stress, collectively suppressing glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and insulin gene expression. Additionally, the activated M1 macrophages directly phagocytose insulin secretory granules and release platelet-derived growth factor to engage platelet-derived growth factor receptors on β-cells, stimulating a compensatory proliferative response that ultimately fails to prevent β-cell failure and inadequate insulin secretion. FFAs: Free fatty acids; TLR: Toll-like receptor; NF-κB: Nuclear factor kappa-B; JNK: Janus tyrosine kinase; ER: Endoplasmic reticulum; MyD88: Myeloid differentiation primary response 88; PDGF: Platelet-derived growth factor; PDGFR: Platelet-derived growth factor receptor.

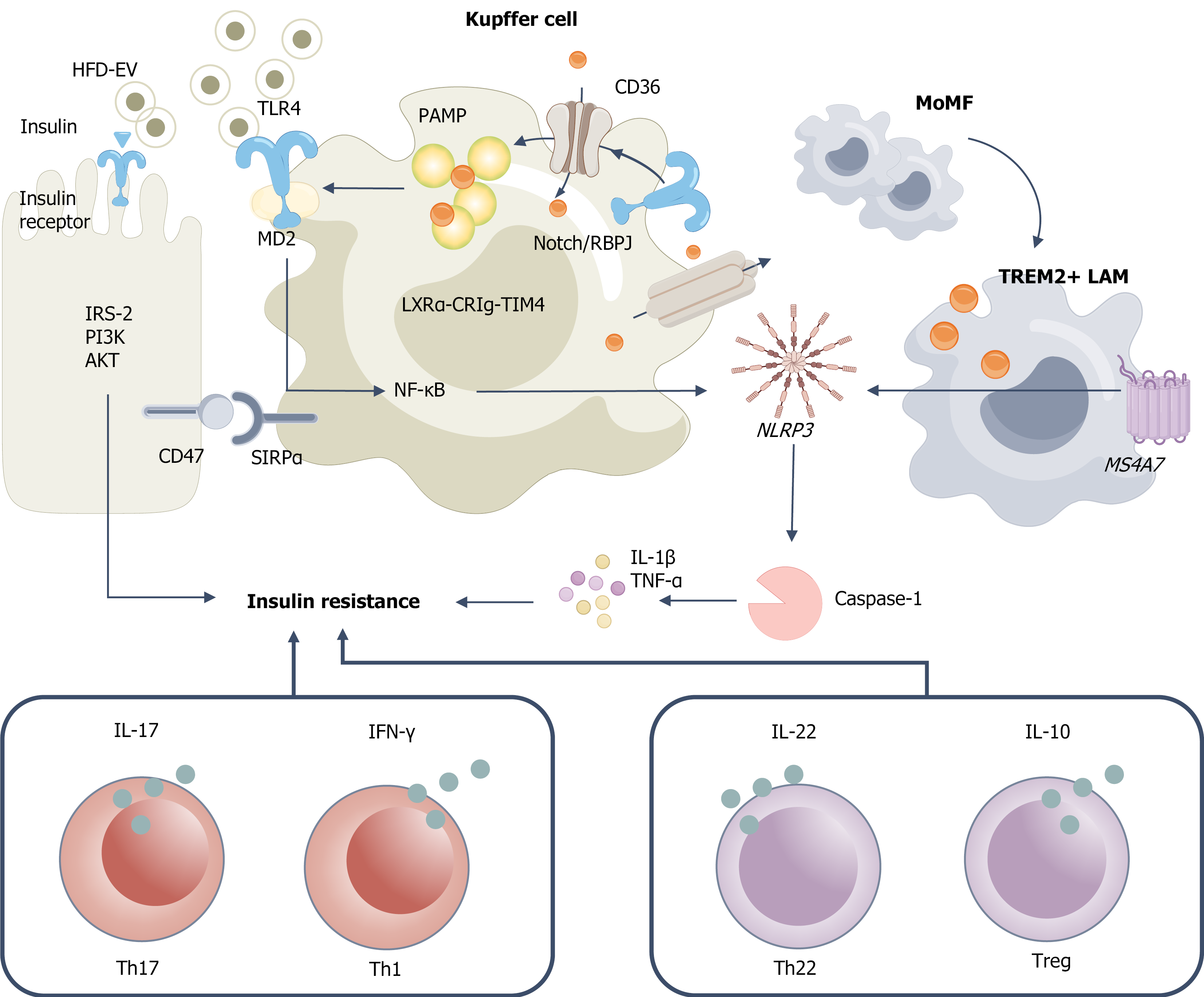

Figure 3 Lipid overload drives innate-adaptive immune imbalance and promotes hepatic insulin resistance.

High-fat diet-derived exosomes and pathogen-associated molecular patterns are recognized through cluster of differentiation (CD) 36-mediated uptake and Toll-like receptor 4/myeloid differentiation protein 2 signaling, respectively, leading to Kupffer cell (KC) activation and initiation of nuclear factor kappa-B priming. Under the influence of Notch/immunoglobulin kappa J region-mediated lineage commitment, monocyte-derived macrophages differentiate toward a triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 lipid-associated macrophage phenotype, whereas the liver X receptor alpha-complement receptor of the immunoglobulin family-T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing protein 4 axis supports the maintenance of homeostatic KC identity. Pro-inflammatory stimuli facilitate NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and caspase-1 activation, resulting in interleukin (IL)-1β maturation and secretion, along with increased production of tumor necrosis factor-α and IL-1β. The CD47-signal regulatory protein α checkpoint serves to modulate phagocytic activity and prevent excessive clearance. These inflammatory factors collectively inhibit the hepatocyte insulin signaling cascade, spanning from the insulin receptor to insulin receptor substrate-2, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, and protein kinase B, thereby promoting insulin resistance. Simultaneously, shifts in the cytokine milieu favor T-cell differentiation away from regulatory T cells/helper T (Th) 22 subsets toward Th1/Th17 dominance, characterized by elevated interferon-gamma and IL-17 and reduced IL-10 and IL-22, which further exacerbates hepatic insulin resistance and inflammation. HFD: High-fat diet; EV: Extracellular vesicle; IRS: Insulin receptor substrate; PI3K: Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; AKT: Protein kinase B; CD: Cluster of differentiation; TLR: Toll-like receptor; MD2: Myeloid differentiation protein 2; SIRPα: Signal regulatory protein α; NF-κB: Nuclear factor kappa-B; PAMP: Pathogen-associated molecular patterns; LXRα-CRIg-TIM4: Liver X receptor alpha-complement receptor of the immunoglobulin family-T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing protein 4; RBPJ: Immunoglobulin kappa J region; MoMF: Monocyte-derived macrophage; TREM: Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells; LAM: Lipid-associated macrophage; IL: Interleukin; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor; IFN: Interferon; Treg: Regulatory T cell; Th: Helper T.

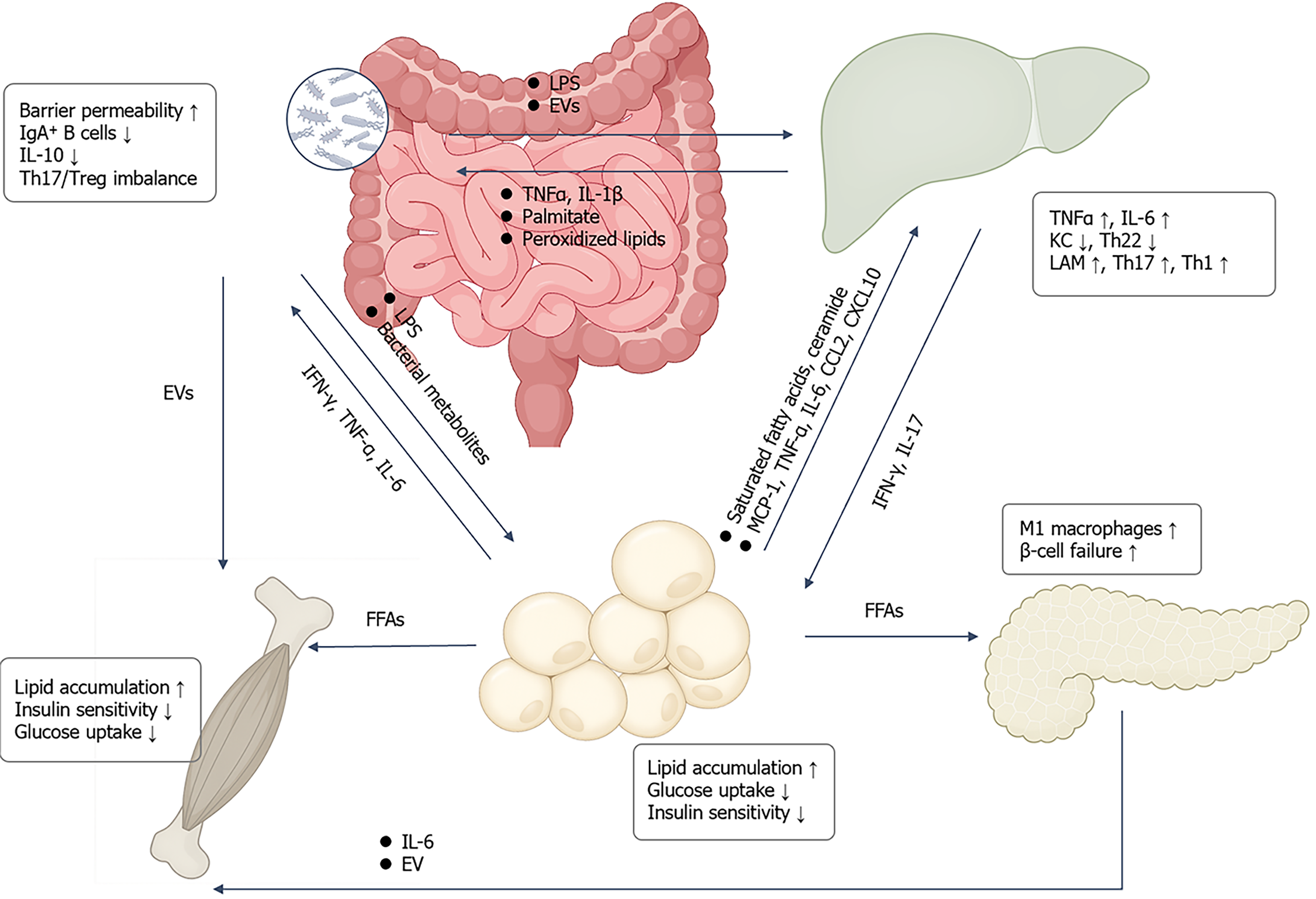

Figure 4 Inter-organ crosstalk drives metabolic inflammation and insulin resistance.

Intestinal dysbiosis and barrier impairment allow lipo

- Citation: Yang HY, Wei Y, Mao Q, Zhao LH. Immune activation induced by dysregulated lipid metabolism in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes. World J Diabetes 2025; 16(12): 114395

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v16/i12/114395.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v16.i12.114395