Published online Feb 15, 2026. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v18.i2.115689

Revised: November 26, 2025

Accepted: December 22, 2025

Published online: February 15, 2026

Processing time: 101 Days and 23.5 Hours

Presenilin-1 (PS-1), a part of the gamma-secretase complex, has been implicated as a tumor promoter in various cancers. PS-1 binds to β-catenin through a large hydrophilic loop region that could lead to gastric tumorigenesis by the phospha

To determine the regulatory correlation among PS-1, β-catenin, and phosphory

Tissue samples from 116 patients with GC were analyzed by immunohistochemistry. Cell lysates from MGC-803 were used to detect protein levels by western blot. Cell invasion ability and metastatic ability were examined in vitro by Transwell invasion and in vivo via tail vein injection, respectively.

The high expression rates of PS-1, β-catenin, and p-PTEN in GC were 60.3% (70/116), 56.9% (66/116), and 47.4% (55/116), respectively, correlating with advanced tumor stages based on tumor invasion, lymph node metastasis, and 5-year survival. PS-1 expression was positively correlated with expression of β-catenin and p-PTEN in patients with GC. PS-1 regulated PTEN phosphorylation and cytoplasmic localization through β-catenin. PS-1 enhanced GC cell invasion via β-catenin.

The expression of PS-1 was positively correlated with that of both β-catenin and p-PTEN in GC. The regulation of PTEN phosphorylation and cytoplasmic localization by PS-1 through β-catenin could be considered potential therapeutic targets to prevent GC tumorigenesis.

Core Tip: The high expression of presenilin 1 was correlated with advanced tumor stages, and its expression was positively correlated with expression of β-catenin and phosphorylation of tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten in patients with gastric cancer (GC). The regulation of phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten phosphorylation and cytoplasmic localization by presenilin 1 through β-catenin as a novel signaling pathway of GC progression could contribute to GC tumorigenesis.

- Citation: Lin X, Lin GF, Gu FT, Li YL. Increasing expression of presenilin 1, β-catenin, and p-PTEN and its regulatory roles on cell invasion in gastric cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2026; 18(2): 115689

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v18/i2/115689.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v18.i2.115689

Gastric cancer (GC) is the second-leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide, particularly in East Asia, where the incidence is high with 40 to 60 cases per 100000 inhabitants[1]. The average 5-year survival rate is no more than 20% due to the lack of sensitive biomarkers for early detection. Presenilin 1 (PS-1) is a component of the γ-secretase complex that cleaves a variety of type I membrane proteins, including the β-amyloid precursor protein, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor, and Notch[2]. Mutations in PS-1 cause the majority of cases of familial Alzheimer’s disease[3].

Recent studies have revealed that PS-1 acts as a regulator of β-catenin and plays a significant role in various tumorigenic processes including cell proliferation, apoptosis, cell adhesion, and others. It has been reported that the loss of PS-1 enhances the β-catenin signaling pathway, contributing to skin tumorigenesis in vitro and in vivo[4]. In our previous study we also demonstrated that PS-1 promoted GC cell invasion and metastasis through the β-catenin signaling pathway[5]. However, the downstream targets of β-catenin regulated by PS-1 in GC remain unclear.

Phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten (PTEN) mutations and/or deletions have been implicated in the development of various cancers. As a negative regulator of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT) pathway, PTEN is frequently inactivated in GC[6,7]. Recent reports suggest that partial loss of PTEN function due to post-translational modifications, such as phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and acetylation, may contribute to the onset of certain cancers.

In this study we observed that phosphorylation of PTEN (p-PTEN) was readily detectable in the majority of GC cell lines and patients with GC and played a significant role in GC progression via the PI3K/AKT pathway. PS-1 is also known to activate the PI3K/AKT cell survival pathway in a γ-secretase-independent manner[8]. However, the me

In the present study we used GC as the experimental model to investigate the role of PS-1 in β-catenin activation and PTEN inactivation and subcellular location that enhance tumor invasion and metastasis. Our results supported a novel functional interaction between the Wnt/β-catenin and PTEN/PI3K pathways that is crucially important for the activity of the protein as a transcription factor in GC.

All the GC samples were from the Affiliated Hospital of Putian University. Among them the 116 paraffin-embedded GC tissues were collected from October 2013 to September 2015. None of the patients in our study received preoperative chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or other biological treatment. All the patients underwent standard D2 lymph node dissection with curative resection (R0). Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy was performed with 5-fluorouracil-based drugs plus oxaliplatin in advanced cases. The study was approved by the Affiliated Hospital of Putian University institutional review board, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The clinical and pathological staging was performed according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer 7th edition of GC tumor-node-metastasis staging.

All patients were systematically followed up by trained doctors based on institutional follow-up protocol in several ways via outpatient service, letter, telephone, mail, or visiting.

Immunohistochemical staining for PS-1, β-catenin, and p-PTEN was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded gastric tissue sections (3 μm thick). Paraffin-embedded tissue sections from GC specimens were given a heat pretreatment of 70 °C for 1 h, then dewaxed in xylene, rehydrated in an ethanol series (100%-50%), and treated in 0.01 mol/L citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for antigen retrieval. After inhibition of endogenous peroxidase activity for 30 min with methanol containing 0.3% H2O2, the sections were stained with a rabbit anti-PS-1 monoclonal antibody (1:200, ab76083, Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), β-catenin (1:200, ab22656, Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), or p-PTEN (1:100, ab109454, Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) at 4 °C overnight. The following experimental procedure was on the basis of the manufacturer’s instructions of the LSAB + kit (Dako, CA, United States). The PS-1, β-catenin, and p-PTEN protein expression was immunohistochemically demonstrated as yellowish to brown staining in gastric glandular cells. Two pathologists blinded to the clinical data reviewed the immunoreactivity for PS-1, β-catenin, p-PTEN protein under a light microscope, and the protein expression was scored independently according to the intensity of cellular staining and the proportion of stained tumor cells. The staining intensity was scored as 0 (no staining), 1 (weak staining, light yellow), 2 (moderate staining, yellow brown), and 3 (strong staining, brown), and the proportion of stained tumor cells was classified as 0 (≤ 5% positive cells), 1 (6% to 25% positive cells), 2 (26% to 50% positive cells), and 3 (≥ 51% positive cells).

The GC cell line MGC-803 was purchased from Shanghai Institute of Cell Biology, China. Cells were homogenized in ristocetin-induced platelet aggregation protein lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors at 4 °C for 30 min before centrifugation at 12000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatants, representing whole cell lysates, were prepared for use in subsequent experiments. The protein concentration was measured using the bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, United States). A total of 40 μg protein from each sample was denatured and loaded into each well, separated by sodium-dodecyl sulfate gel electrophoresis, and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA, United States).

Subsequently, the membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat milk at room temperature for 1 h. The membrane was incubated with anti-PS-1 (1:1000), anti-β-catenin (1:1000), p-PTEN (1:1000), PETN (1:1000, ab32199, Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) or anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (1:1000, ab181602, Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. After washing with wash buffer (10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 150 mmol/L NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20), the membrane was further incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, United States) at a 1:2000 dilution for 1 h at room temperature. Subsequently, the membrane was washed for 30 min with wash buffer and detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Corporation, Arlington Heights, IL, United States).

Lentivirus overexpressing PS-1, short hairpin RNA (shRNA), and control shRNA were purchased from Gene Chem Corporation (GCPL45123, Shanghai, China). The PS-1 complementary DNA open reading frame was cloned into the p-HBLV-IRES-ZsGreen-PGK-Puro plasmid (HanbioTM, Shanghai, China) for lentiviral production. β-catenin small interfering RNA (siRNA) (#6225) and control siRNA (#6568) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, MA, United States. Stable cell lines were screened with puromycin and identified by western blot.

The assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions for the Qproteome Cell Compartment Kit (Qiagen, Germany). A total of 40 μg protein from each fraction was denatured and loaded into each well, and sodium-dodecyl sulfate gel electrophoresis and western blot were conducted as described above. Antibodies against lamin A/C was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Cell invasion was measured using a Transwell chamber (8 μm, 24-well format; Corning, Lowell, MA, United States). To measure invasion diluted Matrigel (BD Biosciences, CA, United States) was used to coat the insert chamber membrane. Then 8 × 104 cells were resuspended in 0.3 mL of serum-free medium and added to the upper chamber while 0.8 mL of medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum was added to the lower chamber. Finally, cells that invaded into the lower chamber were fixed with methanol, stained with crystal violet, and counted in five random fields.

GC cell line MGC-803 with γ-secretase inhibitor (GSI) treated and control were plated in a 24-well plate chamber for 24 h. Cells were washed with 1 × PBS and fixed with an acetone/methanol (1:1) mixture for 15 min at 4 °C. Cells were then washed twice with 1 × PBS, followed by blocking with 10% normal goat serum blocking solution (ZSGB Biotech, China) for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were hybridized with the specific primary antibodies against β-catenin or PTEN diluted in 1 × PBS (1:400) overnight at 4 °C. Cells were washed three times in 1 × PBS and hybridized with fluorescently conjugated secondary antibody (1:200) for 45 min at room temperature. β-catenin and PTEN were detected by fluorescein isothiocyanate red fluorescence. Cells were washed in 1 × PBS, mounted with Vectashield/DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, United States), and examined by a laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica, Germany). At least 200 cells were counted from each experiment.

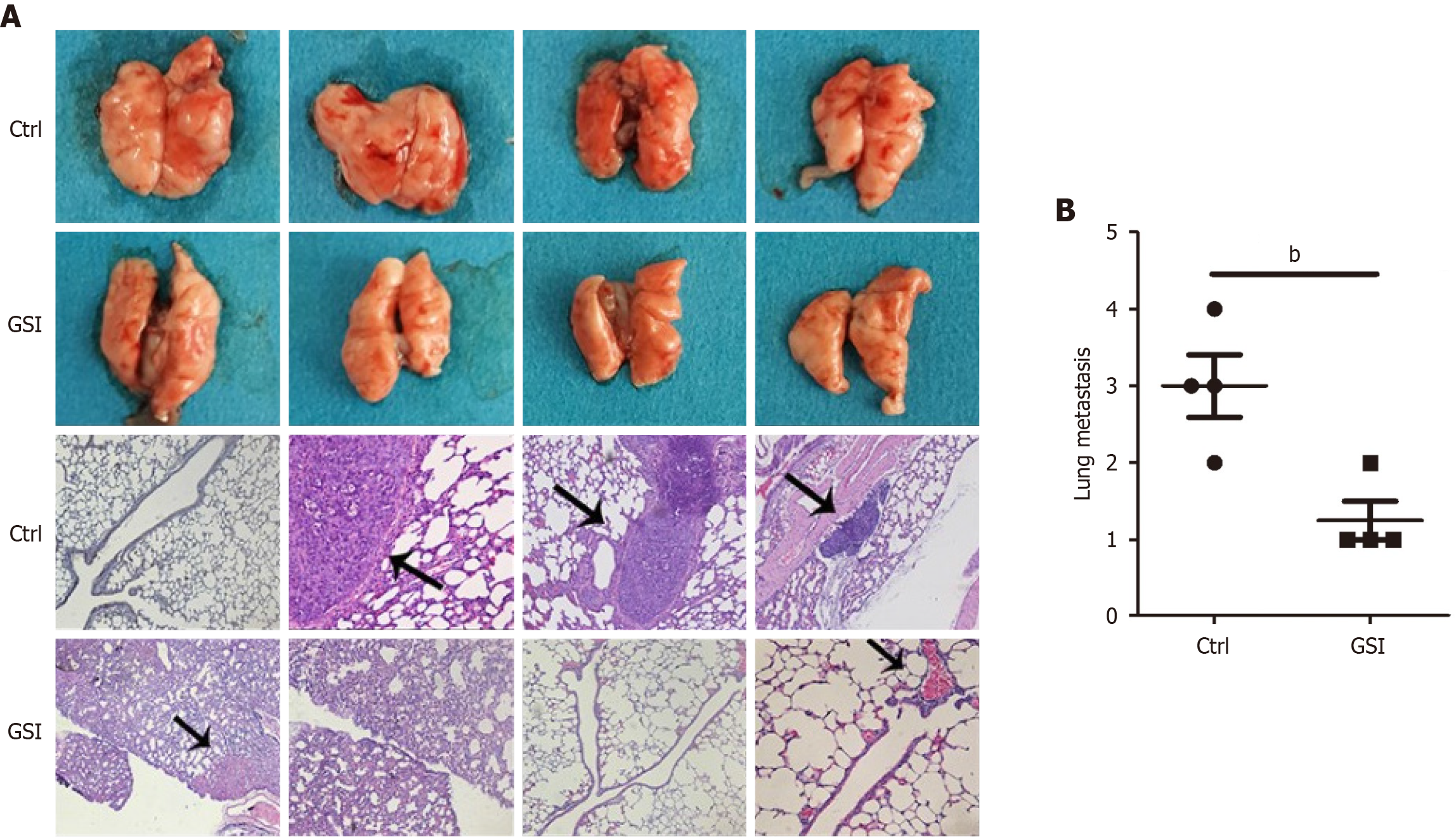

Specific pathogen-free-grade male BALB/c nude mice were purchased from the Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. For the metastasis experiment in vivo, 5 × 106 MGC-803 cells and GSI-treated MGC-803 cells were re

All measurement data are presented as the means ± standard error and were analyzed using SPSS 17.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States) and Prism 5.0 software (GraphPad). The relationships between the PS-1 expression level and clinicopathologic parameters were calculated with the Pearson χ2 test. Survival curves were explored by the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences between two groups were evaluated by the log-rank test. Comparisons were performed using the Student’s t test (two groups) or one-way analysis of variance (multiple groups). The statistical significance threshold was set as P < 0.05.

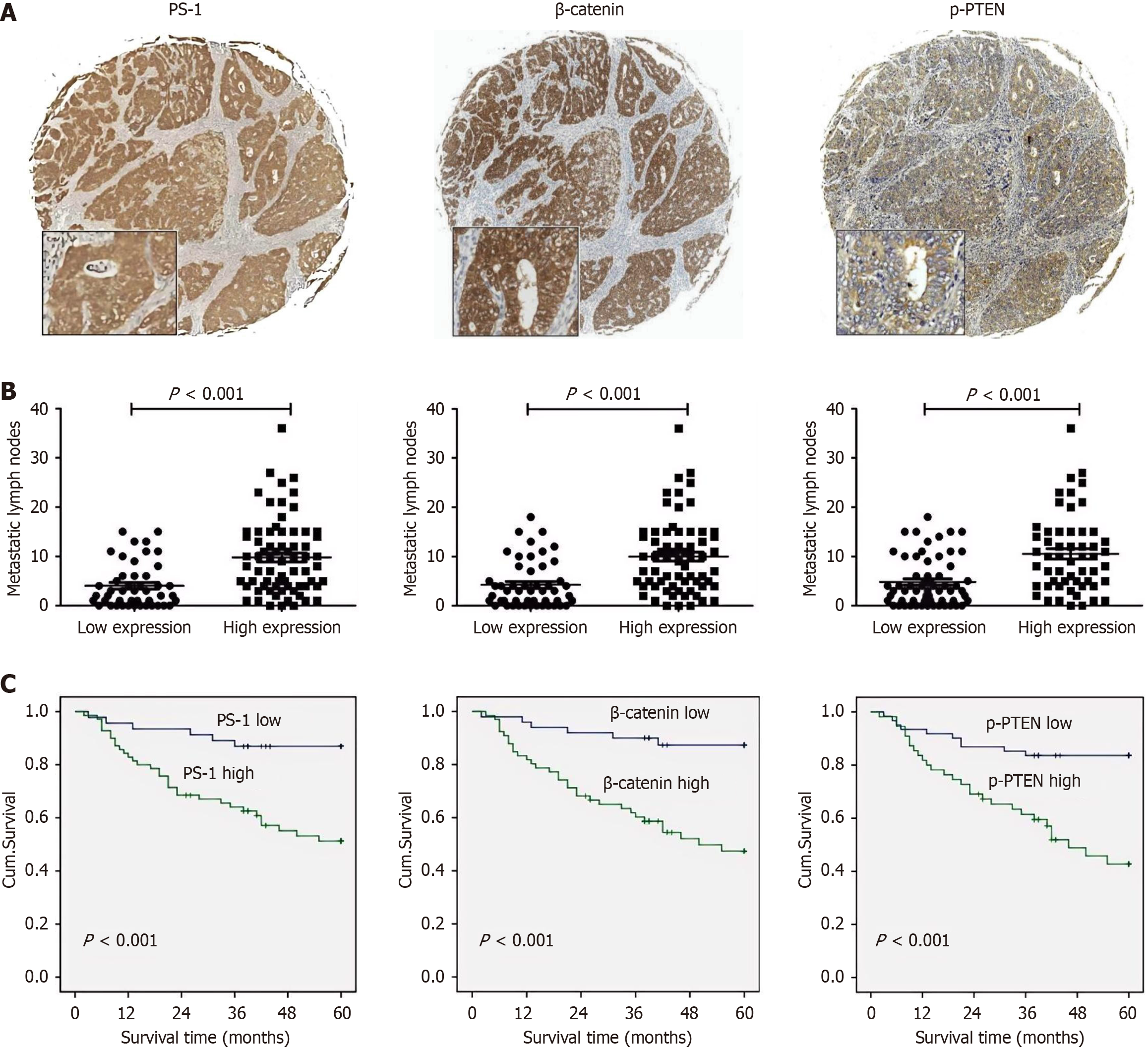

To investigate the associations among PS-1, β-catenin, and p-PTEN, we detected the expression of PS-1, β-catenin, and p-PTEN in the 116 GC samples using immunohistochemistry (Figure 1A). Based on the protein expressions in the GC tissues, we classified samples into two groups: High group and low group. The high expression rates of PS-1, β-catenin, and p-PTEN were 60.3% (70/116), 56.9% (66/116), and 47.4% (55/116), respectively. According to the χ2 test (Table 1), both tumor invasion and lymphatic metastasis were simultaneously associated with PS-1, β-catenin, and p-PTEN, and it was consistent with the results that patients with high expression of PS-1, β-catenin, and p-PTEN have significantly more metastatic lymph nodes than those with low expression (Figure 1B).

| Clinicopathological features | PS-1 | β-catenin | p-PTEN | P value | |||

| Total (n) | High expression | P value | High expression | P value | High expression | ||

| Age (years) | 0.056 | 0.068 | 0.028 | ||||

| ≤ 60 | 63 | 33 | 31 | 24 | |||

| > 60 | 53 | 37 | 35 | 31 | |||

| Gender | 0.673 | 0.919 | 0.604 | ||||

| Male | 91 | 54 | 52 | 42 | |||

| Female | 25 | 16 | 14 | 13 | |||

| Tumor site | 0.147 | 0.272 | 0.405 | ||||

| Upper | 40 | 19 | 23 | 18 | |||

| Middle | 22 | 15 | 16 | 13 | |||

| Lower | 46 | 32 | 24 | 22 | |||

| Mixed | 8 | 4 | 3 | 2 | |||

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.269 | ||||

| ≤ 5 | 59 | 28 | 26 | 25 | |||

| > 5 | 57 | 42 | 40 | 30 | |||

| Grade of differentiation | 0.405 | 0.389 | 0.439 | ||||

| Well and moderate | 55 | 31 | 29 | 24 | |||

| Poor and not | 61 | 39 | 37 | 31 | |||

| Neurovascular invasion | 0.433 | 0.031 | 0.014 | ||||

| Negative | 54 | 29 | 25 | 19 | |||

| Positive | 62 | 41 | 41 | 36 | |||

| Depth of invasion | < 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | ||||

| T1 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |||

| T2 | 11 | 2 | 2 | 0 | |||

| T3 | 48 | 25 | 26 | 22 | |||

| T4 | 53 | 42 | 38 | 32 | |||

| Lymphatic metastasis | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.003 | ||||

| N0 | 15 | 3 | 3 | 2 | |||

| N1 | 20 | 7 | 7 | 7 | |||

| N2 | 35 | 21 | 20 | 16 | |||

| N3 | 46 | 39 | 36 | 30 | |||

| Distal metastasis | 0.041 | 0.112 | 0.004 | ||||

| M0 | 109 | 63 | 60 | 48 | |||

| M1 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | |||

Moreover, we compared the overall survival of patients categorized by PS-1, β-catenin, and p-PTEN expression. The overall survival rate of patients with high PS-1 expression was significantly lower than that of patients with low PS-1 expression. Similar results were observed in β-catenin and p-PTEN (Figure 1C). Interestingly, using the Spearman rank correlation test, we found that PS-1 expression levels were positively correlated with both β-catenin and p-PTEN levels in patients with GC. In the samples with high PS-1 expression, both β-catenin and p-PTEN protein expression tended to be significantly higher than that in the low PS-1 expression samples (r values were 0.362 and 0.471, respectively, Table 2). In the samples with high β-catenin expression, p-PTEN protein expression tended to be significantly higher than that in the low β-catenin expression samples (r value was 0.338, Table 2). These results suggested that the functional effects of PS-1 in GC could probably be conducted by β-catenin and p-PTEN.

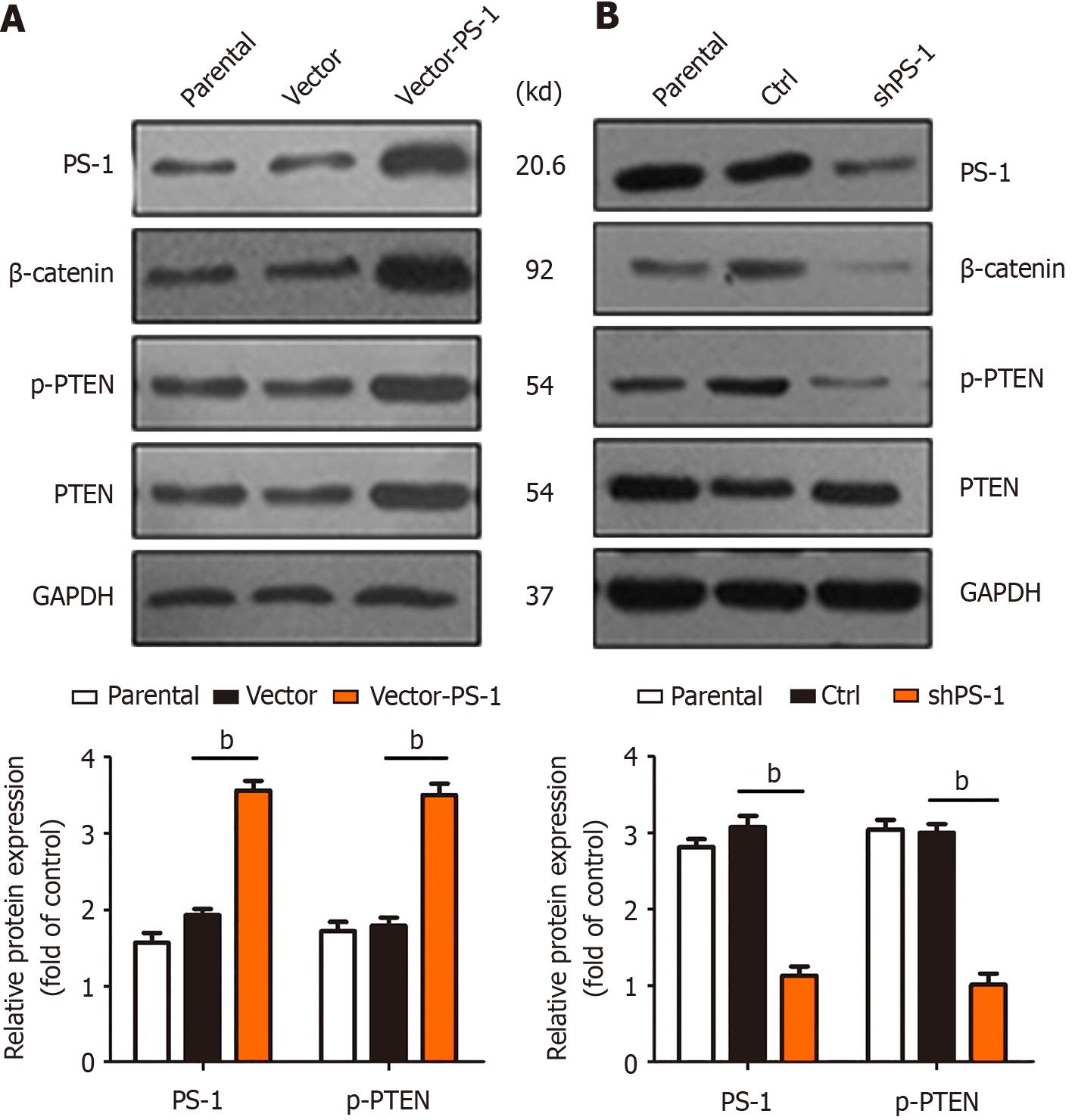

MGC-803 GC cells were successfully infected with PS-1 overexpression (vector-PS-1) and PS-1 knockdown (ctrl-shPS-1) lentivirus. We examined protein levels of PS-1, β-catenin, p-PTEN, and PTEN by western blot analysis. We found that the protein levels of p-PTEN and β-catenin were noticeably decreased with downregulation of PS-1 (Figure 2A) while the level of p-PTEN and β-catenin were increased when PS-1 was upregulated (Figure 2B). However, PTEN protein expression was not significantly changed in MGC-803 cells either in the overexpression group or in the knockdown group. These results suggested that PS-1 might affect phosphorylation of PTEN as well as β-catenin expression but did not affect total PTEN protein expression.

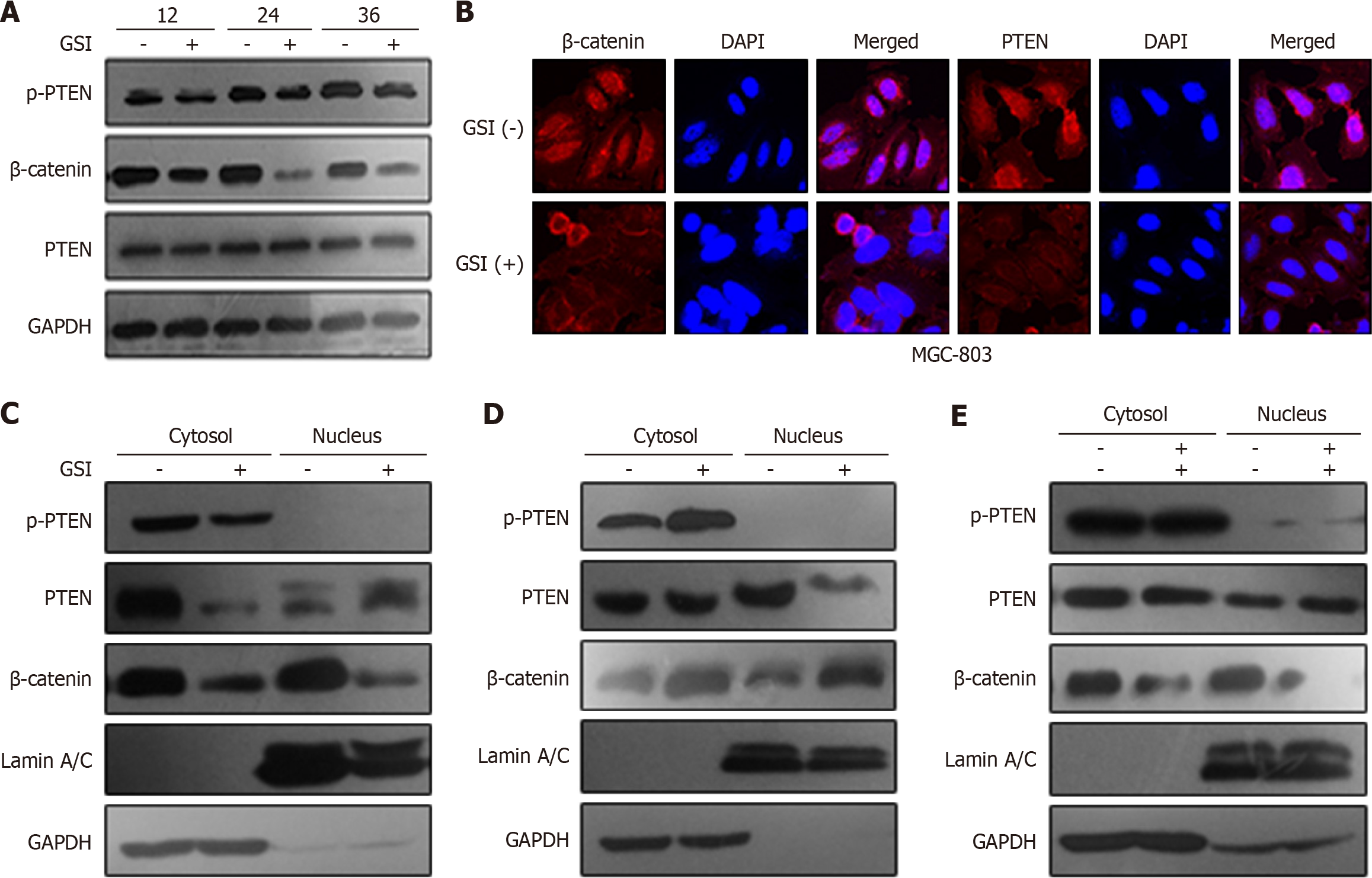

We performed a subcellular fraction assay to measure subcellular localization of β-catenin, PTEN, and p-PTEN by GSI treatment or lentivirus PS-1. GSI obviously decreased expression of β-catenin (in both cytoplasm and nucleus) and p-PTEN (just in cytoplasm) without effecting the total amount of PTEN. Interestingly, nuclear localization of PTEN upon GSI treatment was also consistently observed in GC cells (Figure 3A-C). Overexpression of PS-1 induced β-catenin expression in both the cytoplasm and nucleus with an increase in p-PTEN only in the cytoplasm (Figure 3D). We further investigated whether PS-1 regulated PTEN phosphorylation through β-catenin. As expected cotransfection of β-catenin siRNA and lentivirus PS-1 could rescue the phosphorylation of PTEN by PS-1 (Figure 3E). These data indicated that PS-1 regulated PTEN phosphorylation and cytoplasmic localization through activating β-catenin in GC cells.

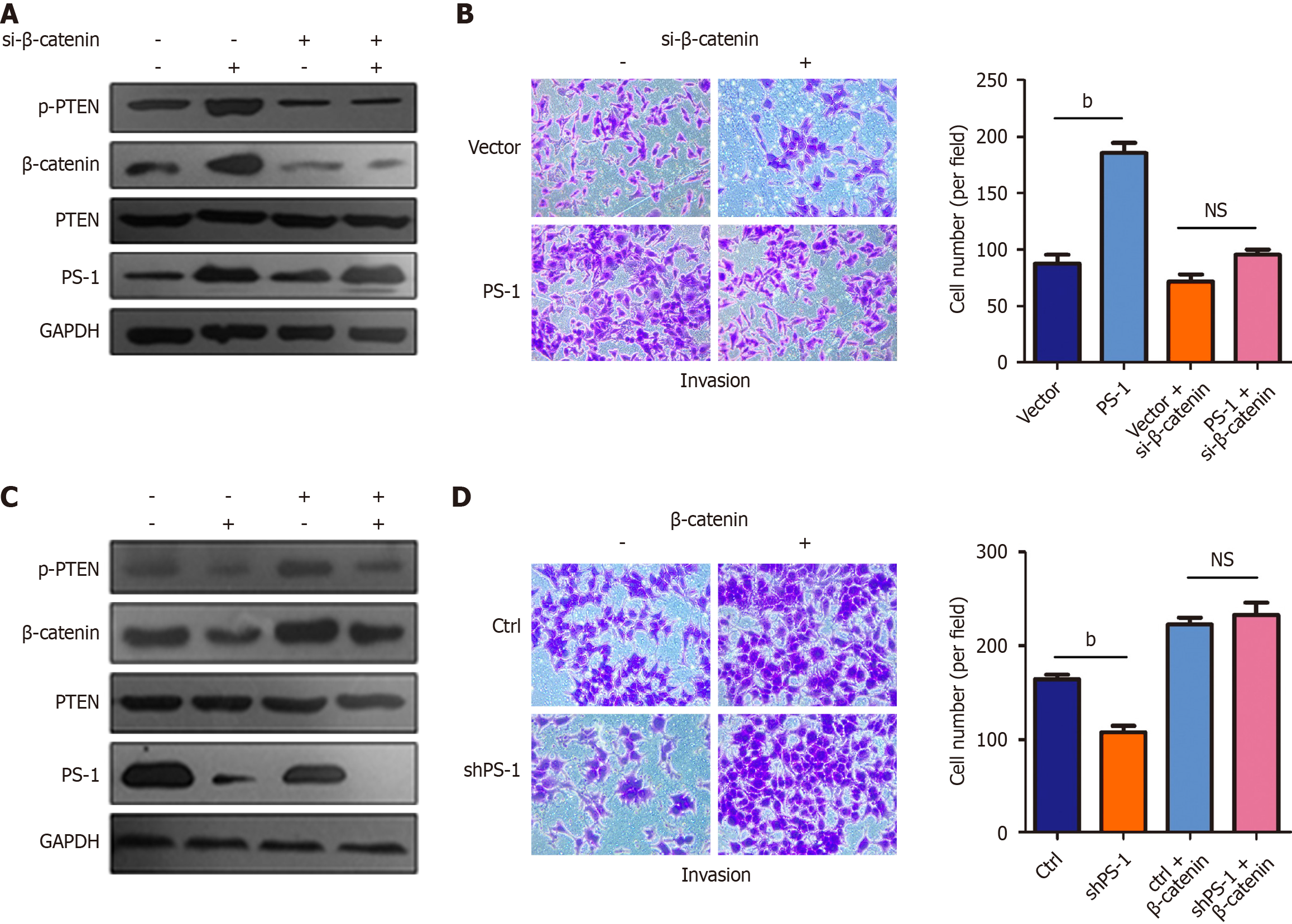

To investigate the functional significance of the variation of β-catenin regulated by PS-1, we first employed Transwell invasion assay to assess the effect of PS-1 overexpression on GC cell migration. The results showed that MGC-803 cells stably infected with lentivirus PS-1 exhibited promotion of cell invasion compared with the control cells. However, cotransfection of β-catenin siRNA and lentivirus PS-1 could rescue the promotion of cell invasion by PS-1. Furthermore, we noticed that PTEN phosphorylation was noticeably decreased and was accompanied by decreasing β-catenin (Figure 4A and B). In contrast, shRNA-mediated knockdown of PS-1 in MGC-803 cells led to significantly reducing cell invasion. Overexpression of β-catenin completely reversed the effect of PS-1 knockdown in invasion. Importantly, the protein level of p-PTEN was positively correlated with the protein level of PS-1 and β-catenin (Figure 4C and D). These data provided evidence that PS-1 promoted the invasion of GC cells via enhancing β-catenin expression that might increase PTEN phosphorylation.

To demonstrate that PS-1, a critical component of γ-secretase, is highly relevant for GC tumorigenesis, we conducted a preclinical assay to investigate the impact of GSI on immunocompromised mice. We randomly divided the nude mice into two groups and injected the same amount of MGC-803 cells into the lateral tail veins. One group was treated with normal saline (control group), and the other group was treated with 10 mg/kg GSI (GSI group). Three months after injection, the mice were sacrificed to evaluate metastatic nodules in the lungs (Figure 5). We found mice injected with saline harbored more metastatic foci throughout their lungs compared with those injected with the GSI. The result showed the potential therapeutic efficacy of GSI for the treatment of human GC.

PS-1, a multipass transmembrane protein important in development, is tightly linked to many cases of early-onset familial Alzheimer’s disease indicating a causal relationship between these mutants and Alzheimer’s disease pathology[9-11]. Recently, an increasing number of reports have shown that PS-1 plays an exclusive and significant role in various tumorigenic processes including cell proliferation, apoptosis, cell adhesion and others[12,13]. In prostate cancer PS-1 was demonstrated to induce intramembrane proteolysis of transforming growth factor-β receptor I, promoting transforming growth factor-β-induced invasion of cancer cells in vitro[14]. Enhanced expression of proteolytically active PS-1 is associated with E-cadherin proteolysis and nuclear translocation, which promotes peritoneal metastasis in colorectal cancer[15].

However, little is known regarding the downstream targets of PS-1 in the development of GC. We therefore aimed to evaluate the involvement of PS-1 in GC. In the current study we found that the expression of PS-1 in patients with GC was higher in tumor tissues than in adjacent nontumor tissues, and these patients exhibited more lymph node metastases and a poorer prognosis. In addition, our study was the first to verify the positive correlation between PS-1 and β-catenin levels in GC, providing scientific clinical experimental evidence for further in vitro research. In the in vitro cell model, overexpression of PS-1 markedly promoted cell invasiveness, whereas PS-1 knockdown significantly inhibited GC cell invasion. These effects could be reversed by regulation of β-catenin levels. These results were consistent with those obtained for gastric tumor tissues, indicating that PS-1 likely acts as a tumor promoter to enhance tumor cell invasion by β-catenin.

Several studies focusing on the role of PS-1 and β-catenin have been published in a broad variety of cancer types. A study reported that myoinositol-induced downregulation of PS-1 could reduce β-catenin translocation, which interfered with the epithelial-mesenchymal transition and led to anticancer activity[16]. In addition, in our previous study we also presented that PS-1 promoted cell invasion and metastasis through β-catenin in GC[5]. However, it has also been reported that PS-1 deficiency resulted in increased β-catenin stability in tumorigenesis in vitro and in vivo[4,17,18]. The diverse and controversial impact of PS-1 on β-catenin in the above-mentioned tumors probably resulted from the activation of a variety of downstream signaling pathways. Overall, our findings identified a PS-1/β-catenin signaling pathway as a novel component of the carcinogenic machinery in GC.

PTEN was independently discovered by three laboratories in 1997 as a tumor suppressor that was often lost in tumorigenesis[19-21]. Later studies established that PTEN played a critical role in growth and survival in various cancer types[22,23]. Recent studies indicated that regulation of PTEN in GC included mutation, promoter hypermethylation, etc. However, it remains to be investigated whether other regulatory mechanisms account for the inactivation of PTEN and the induction of tumorigenesis in GC. Indeed, several studies demonstrated that phosphorylation of the PTEN protein (including Ser380, Thr382, and Thr383) led to a loss of phosphatase activities and in turn resulted in a loss of tumor suppressor function. This was the most important mechanism of modification of PTEN in some types of tumors[24,25].

In the current study we explored whether the phosphorylation of PTEN occurred and how it was regulated in GC. Our results indicated that the high expression rate of p-PTEN in gastric tumor tissues was higher than that in nontumor tissues. Cytoplasmic p-PTEN expression levels were positively correlated with both PS-1 and β-catenin levels in patients with GC, and this was consistent with in vitro results that PS-1 regulated PTEN phosphorylation and subcellular lo

Interestingly, although p-PTEN was upregulated by PS-1, the expression of total PTEN remained unchanged. This was inconsistent with previous studies showing a loss of PTEN activity through a decrease in total PTEN expression level and phosphorylation of its C-terminus in lung cancer cells[28]. It is possible that this was just the decreasing unphosphorylated PTEN that resulted in abrogation of the tumor suppressive effect of PTEN in GC. However, it still remains unclear whether PTEN is phosphorylated by the PS-1/β-catenin complex directly or indirectly. In the future it will be interesting to investigate how PTEN is phosphorylated by the PS-1/β-catenin complex and whether p-PTEN performs biological functions in GC.

Our current study represented the first investigation into the functional relationship among PS-1, β-catenin, and p-PTEN in GC progression through a survey of tumor tissues with well-documented clinical pathology and history. We also have demonstrated that PS-1 regulated PTEN phosphorylation and cytoplasmic localization through β-catenin. This work identified a novel PS-1/β-catenin/PTEN signaling axis contributing to GC pathogenesis. It mechanistically explained how high PS-1 expression promoted GC aggressiveness by inactivating the key tumor suppressor PTEN via β-catenin-dependent phosphorylation and mislocalization. Components of this pathway (PS-1, β-catenin, specific PTEN kinases) represent potential therapeutic targets for GC. Taken together, our findings indicate that PS-1, β-catenin, and p-PTEN are important for GC progression and could be considered potential therapeutic targets to prevent GC tumorigenesis.

| 1. | Washington K. 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual: stomach. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:3077-3079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 702] [Cited by in RCA: 820] [Article Influence: 54.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zhang H, Liu R, Wang R, Hong S, Xu H, Zhang YW. Presenilins regulate the cellular level of the tumor suppressor PTEN. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29:653-660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Selkoe DJ, Wolfe MS. Presenilin: running with scissors in the membrane. Cell. 2007;131:215-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 264] [Cited by in RCA: 283] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Xia X, Qian S, Soriano S, Wu Y, Fletcher AM, Wang XJ, Koo EH, Wu X, Zheng H. Loss of presenilin 1 is associated with enhanced beta-catenin signaling and skin tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10863-10868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Li P, Lin X, Zhang JR, Li Y, Lu J, Huang FC, Zheng CH, Xie JW, Wang JB, Huang CM. The expression of presenilin 1 enhances carcinogenesis and metastasis in gastric cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:10650-10662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Li YL, Tian Z, Wu DY, Fu BY, Xin Y. Loss of heterozygosity on 10q23.3 and mutation of tumor suppressor gene PTEN in gastric cancer and precancerous lesions. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:285-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kang YH, Lee HS, Kim WH. Promoter methylation and silencing of PTEN in gastric carcinoma. Lab Invest. 2002;82:285-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kim SJ, Lee HW, Baek JH, Cho YH, Kang HG, Jeong JS, Song J, Park HS, Chun KH. Activation of nuclear PTEN by inhibition of Notch signaling induces G2/M cell cycle arrest in gastric cancer. Oncogene. 2016;35:251-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Shen J, Bronson RT, Chen DF, Xia W, Selkoe DJ, Tonegawa S. Skeletal and CNS defects in Presenilin-1-deficient mice. Cell. 1997;89:629-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 713] [Cited by in RCA: 712] [Article Influence: 24.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 10. | Singh N, Talalayeva Y, Tsiper M, Romanov V, Dranovsky A, Colflesh D, Rudamen G, Vitek MP, Shen J, Yang X, Goldgaber D, Schwarzman AL. The role of Alzheimer's disease-related presenilin 1 in intercellular adhesion. Exp Cell Res. 2001;263:1-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Pigino G, Pelsman A, Mori H, Busciglio J. Presenilin-1 mutations reduce cytoskeletal association, deregulate neurite growth, and potentiate neuronal dystrophy and tau phosphorylation. J Neurosci. 2001;21:834-842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Baki L, Marambaud P, Efthimiopoulos S, Georgakopoulos A, Wen P, Cui W, Shioi J, Koo E, Ozawa M, Friedrich VL Jr, Robakis NK. Presenilin-1 binds cytoplasmic epithelial cadherin, inhibits cadherin/p120 association, and regulates stability and function of the cadherin/catenin adhesion complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:2381-2386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Roperch JP, Alvaro V, Prieur S, Tuynder M, Nemani M, Lethrosne F, Piouffre L, Gendron MC, Israeli D, Dausset J, Oren M, Amson R, Telerman A. Inhibition of presenilin 1 expression is promoted by p53 and p21WAF-1 and results in apoptosis and tumor suppression. Nat Med. 1998;4:835-838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gudey SK, Sundar R, Mu Y, Wallenius A, Zang G, Bergh A, Heldin CH, Landström M. TRAF6 stimulates the tumor-promoting effects of TGFβ type I receptor through polyubiquitination and activation of presenilin 1. Sci Signal. 2014;7:ra2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Céspedes MV, Larriba MJ, Pavón MA, Alamo P, Casanova I, Parreño M, Feliu A, Sancho FJ, Muñoz A, Mangues R. Site-dependent E-cadherin cleavage and nuclear translocation in a metastatic colorectal cancer model. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:2067-2079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bizzarri M, Dinicola S, Bevilacqua A, Cucina A. Broad Spectrum Anticancer Activity of Myo-Inositol and Inositol Hexakisphosphate. Int J Endocrinol. 2016;2016:5616807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kang DE, Soriano S, Xia X, Eberhart CG, De Strooper B, Zheng H, Koo EH. Presenilin couples the paired phosphorylation of beta-catenin independent of axin: implications for beta-catenin activation in tumorigenesis. Cell. 2002;110:751-762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bhoumik A, Fichtman B, Derossi C, Breitwieser W, Kluger HM, Davis S, Subtil A, Meltzer P, Krajewski S, Jones N, Ronai Z. Suppressor role of activating transcription factor 2 (ATF2) in skin cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1674-1679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Li J, Yen C, Liaw D, Podsypanina K, Bose S, Wang SI, Puc J, Miliaresis C, Rodgers L, McCombie R, Bigner SH, Giovanella BC, Ittmann M, Tycko B, Hibshoosh H, Wigler MH, Parsons R. PTEN, a putative protein tyrosine phosphatase gene mutated in human brain, breast, and prostate cancer. Science. 1997;275:1943-1947. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3525] [Cited by in RCA: 3609] [Article Influence: 124.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Steck PA, Pershouse MA, Jasser SA, Yung WK, Lin H, Ligon AH, Langford LA, Baumgard ML, Hattier T, Davis T, Frye C, Hu R, Swedlund B, Teng DH, Tavtigian SV. Identification of a candidate tumour suppressor gene, MMAC1, at chromosome 10q23.3 that is mutated in multiple advanced cancers. Nat Genet. 1997;15:356-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2004] [Cited by in RCA: 2053] [Article Influence: 70.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Li DM, Sun H. TEP1, encoded by a candidate tumor suppressor locus, is a novel protein tyrosine phosphatase regulated by transforming growth factor beta. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2124-2129. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Tamura M, Gu J, Takino T, Yamada KM. Tumor suppressor PTEN inhibition of cell invasion, migration, and growth: differential involvement of focal adhesion kinase and p130Cas. Cancer Res. 1999;59:442-449. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Stambolic V, Suzuki A, de la Pompa JL, Brothers GM, Mirtsos C, Sasaki T, Ruland J, Penninger JM, Siderovski DP, Mak TW. Negative regulation of PKB/Akt-dependent cell survival by the tumor suppressor PTEN. Cell. 1998;95:29-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1845] [Cited by in RCA: 1926] [Article Influence: 68.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Fragoso R, Barata JT. Kinases, tails and more: regulation of PTEN function by phosphorylation. Methods. 2015;77-78:75-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Vazquez F, Ramaswamy S, Nakamura N, Sellers WR. Phosphorylation of the PTEN tail regulates protein stability and function. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5010-5018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 593] [Cited by in RCA: 638] [Article Influence: 24.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Bassi C, Ho J, Srikumar T, Dowling RJ, Gorrini C, Miller SJ, Mak TW, Neel BG, Raught B, Stambolic V. Nuclear PTEN controls DNA repair and sensitivity to genotoxic stress. Science. 2013;341:395-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 324] [Cited by in RCA: 344] [Article Influence: 26.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Rahdar M, Inoue T, Meyer T, Zhang J, Vazquez F, Devreotes PN. A phosphorylation-dependent intramolecular interaction regulates the membrane association and activity of the tumor suppressor PTEN. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:480-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 221] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Aoyama D, Hashimoto N, Sakamoto K, Kohnoh T, Kusunose M, Kimura M, Ogata R, Imaizumi K, Kawabe T, Hasegawa Y. Involvement of TGFβ-induced phosphorylation of the PTEN C-terminus on TGFβ-induced acquisition of malignant phenotypes in lung cancer cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e81133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/