Published online Jan 15, 2026. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v18.i1.113816

Revised: October 12, 2025

Accepted: November 24, 2025

Published online: January 15, 2026

Processing time: 130 Days and 21.1 Hours

Regorafenib is approved as a second-line treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), but its comparative efficacy remains under evaluation.

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of regorafenib vs other second-line therapies in advanced HCC.

This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted in accordance with PRISMA guidelines. A comprehensive search of PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library was performed on June 6, 2025. Studies were included if they reported at least one relevant clinical outcome: Overall survival, progression-free survival, objective response rate, or disease control rate. Data was extracted independently by two reviewers. Quality was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 tool for randomized controlled trials and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for cohort studies. Pooled effect estimates were calculated using random- or fixed-effects models depending on the degree of heterogeneity. Sen

Nine studies met inclusion criteria. Regorafenib significantly improved overall survival compared to controls [weighted mean difference = 2.54 months; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.26-4.81; P < 0.05], but no significant benefit was ob

Regorafenib offers a survival advantage in advanced HCC but does not significantly improve tumor response rates compared to alternative therapies.

Core Tip: This study presents a comprehensive synthesis of current evidence regarding regorafenib’s clinical performance as a second-line treatment in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Utilizing data from nine eligible studies, our meta-analysis provides an updated assessment of survival outcomes and tumor response metrics. Notably, regorafenib demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in overall survival compared to control groups, while objective tumor response rates did not show superiority, particularly when compared to immunotherapies such as nivolumab. Our results highlight regorafenib’s survival benefit and its role within a competitive therapeutic landscape.

- Citation: Cheng Z, Yue AM. Efficacy of regorafenib in the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2026; 18(1): 113816

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v18/i1/113816.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v18.i1.113816

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) represents the most common primary malignancy of the liver and constitutes a significant global health burden. Liver cancer is the sixth most commonly diagnosed cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, with HCC accounting for approximately 75%-85% of all primary liver cancers[1,2]. The majority of HCC cases are diagnosed at an advanced stage, at which point curative options such as surgical resection, liver transplantation, or local ablative therapies are no longer feasible. As a result, systemic therapy remains the cor

Regorafenib, an oral multi-kinase inhibitor structurally related to sorafenib, has emerged as a promising second-line agent. It targets a broader spectrum of kinases involved in tumor angiogenesis (e.g., vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1-3, tyrosine kinase with immunoglobulin and epidermal growth factor homology domains 2), oncogenesis (e.g., KIT, RET, RAF-1, BRAF), and the tumor microenvironment (e.g., platelet-derived growth factor receptor, fibroblast growth factor receptor). The efficacy of regorafenib was first established in the RESORCE trial, a pivotal phase III randomized controlled trial (RCT) demonstrating that regorafenib significantly prolonged overall survival (OS) compared to placebo in patients with advanced HCC who had progressed on sorafenib and maintained adequate liver function (Child-Pugh A)[5-7]. Although widely adopted, evidence on the comparative effectiveness and safety of regorafenib vs alternative second-line treatments remains inconsistent. These discrepancies may reflect differences in patient selection, baseline liver function, regional treatment patterns, and study design[8-10].

Given the accumulating yet heterogeneous body of evidence, a comprehensive synthesis of the available data is warranted to clarify the therapeutic value of regorafenib in advanced HCC. A systematic review and meta-analysis allows for quantitative evaluation of efficacy outcomes, including OS, progression-free survival (PFS), objective response rate (ORR), and disease control rate (DCR). This type of analysis is essential for informing evidence-based clinical decisions and refining second-line treatment strategies. The objective of this study is to determine whether regorafenib provides a significant survival or tumor response benefit compared to other approved or commonly used second-line therapies in patients with advanced HCC.

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines[11]. A comprehensive literature search was performed across four major electronic databases: PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library. The search was carried out on June 6, 2025, and no restrictions were placed on the date of publication to ensure the inclusion of all potentially relevant studies. The full search strings for each database are provided in Supplementary Table 1. To minimize selection bias, no language restrictions were applied. The reference lists of all included articles and relevant review papers were manually screened to identify additional eligible studies. Duplicate records were removed using EndNote reference management software, and titles and abstracts were independently screened by two reviewers for relevance. Full-text articles were then assessed for eligibility according to the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Studies were considered eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis if they met all of the following criteria: (1) Population: Studies involving adult patients (≥ 18 years) diagnosed with advanced, unresectable, or metastatic HCC, confirmed by histological, cytological, or imaging criteria, were included; (2) Intervention: Studies that evaluated regorafenib as monotherapy or in combination with other agents for the treatment of advanced HCC; (3) Outcomes: Studies were required to report at least one of the following clinical outcomes: OS, PFS, ORR, and DCR; and (4) Study design: RCTs, prospective or retrospective cohort studies, and single-arm clinical trials were included.

Studies were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: (1) Population: Studies involving patients with early-stage HCC, recurrent HCC after curative resection, or mixed tumor types (e.g., cholangiocarcinoma) without separate data on advanced HCC were excluded; (2) Intervention: Studies that did not include regorafenib as a treatment modality, or those evaluating regorafenib in combination with non-standard experimental agents without control groups, were excluded; (3) Outcomes: Studies that did not report relevant efficacy or safety outcomes, or lacked sufficient data to estimate effect sizes or confidence intervals, were excluded; (4) Study design: Case reports, case series with fewer than 10 patients, narrative reviews, editorials, expert opinions, meeting abstracts, and conference proceedings were excluded; and (4) Duplicates: Duplicate publications or studies with overlapping data were excluded; in such cases, the most comprehensive and recent version was retained for analysis.

Two independent reviewers screened the literature and extracted data in accordance with the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Initial screening was conducted by reviewing titles and abstracts to exclude clearly irrelevant studies. Full texts of potentially eligible articles were then reviewed to determine final inclusion. Relevant data were extracted using a standardized data collection form and cross-checked for consistency. In cases of disagreement, a third reviewer was consulted to resolve discrepancies through discussion and consensus. The extracted information included the first author’s name, year of publication, study design, sample size, patient demographics (age and sex), details of the intervention (regorafenib dosage and administration), and reported clinical outcomes such as OS, PFS, ORR, and DCR.

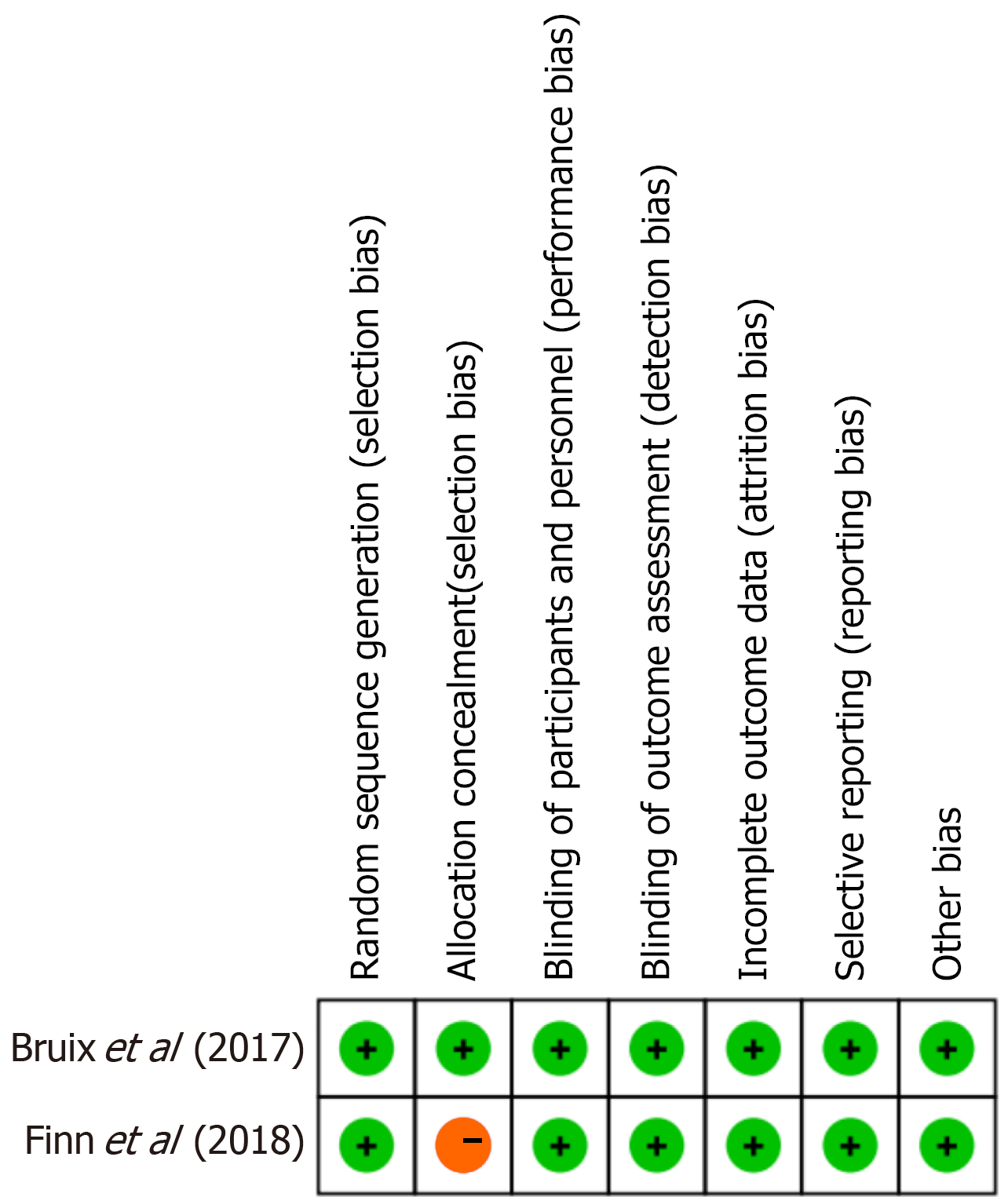

For RCTs, the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 tool was employed[12]. This tool assesses bias across five domains: (1) The ran

For observational cohort studies, the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to assess study quality[13]. The NOS evaluates studies based on three broad perspectives: (1) Selection of study groups (maximum of 4 points); (2) Comparability of groups (maximum of 2 points); and (3) Ascertainment of outcomes (maximum of 3 points). A total score ranging from 0 to 9 was assigned to each study, with higher scores indicating better methodological quality. Studies scoring ≥ 7 were considered to be of high quality, scores of 5-6 were considered moderate quality, and scores < 5 were classified as low quality.

The risk of bias and methodological quality of all included studies were independently assessed by two reviewers. The results of the evaluations were cross-checked, and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus. If disagreements could not be reconciled, a third reviewer was consulted for adjudication. All quality assessment results were incorporated into the final analysis and considered in the interpretation of findings to account for potential sources of bias and study heterogeneity.

All statistical analyses were conducted using Review Manager version 5.4 (Cochrane Collaboration) and Stata version 18.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, United States). For studies reporting median OS or PFS with ranges or interquartile intervals, the values were converted to mean ± SD using established formulas (Hozo et al[14], 2005) to enable pooling of continuous data as weighted mean differences (WMDs). Time to progression data were handled in the same manner to ensure consistency across survival outcomes. Heterogeneity among studies was evaluated using Cochran’s Q test and quantified by the I2 statistic, which estimates the percentage of total variation due to heterogeneity rather than chance. An I2 value ≤ 50% and a P value ≥ 0.10 were considered to indicate low or acceptable heterogeneity, whereas an I2 > 50% or P < 0.10 suggested substantial heterogeneity. When heterogeneity was low (I2 ≤ 50%), a fixed-effects model (Mantel-Haenszel method) was applied, assuming that all studies estimated a common underlying effect size. When heterogeneity was moderate to high (I2 > 50%), a random-effects model (DerSimonian-Laird method) was used, which accounts for between-study variability and provides more conservative estimates. To explore sources of heterogeneity, subgroup analyses were performed when sufficient data were available, based on factors such as study design, geographic region, line of treatment, or type of control intervention. Additionally, sensitivity analyses were conducted by sequentially removing one study at a time to assess the robustness and stability of the pooled estimates. Publication bias was evaluated using Egger’s regression test, with a P value < 0.05 suggesting potential bias. A two-sided P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses unless otherwise specified.

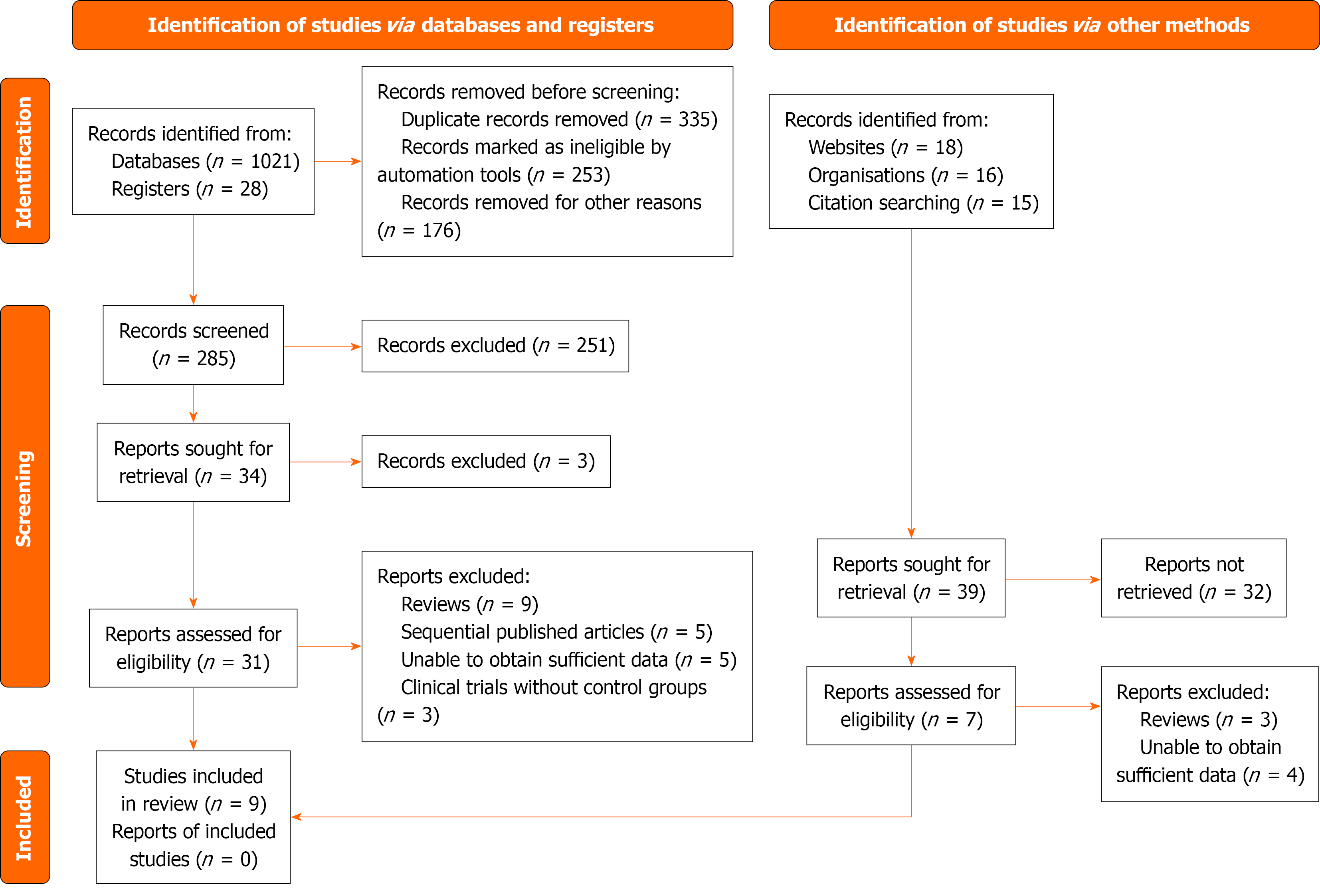

A total of 1049 records were identified through database and registry searches, including 1021 records from databases (PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library) and 28 from trial registries. Before screening, 764 records were removed due to duplication (n = 335), automatic exclusion by filtering tools (n = 253), or other reasons (n = 176). The remaining 285 records were screened by title and abstract, of which 251 were excluded as irrelevant. Full-text retrieval was attempted for 34 articles, but 3 could not be accessed. Among the 31 full-text articles assessed for eligibility, 22 were excluded for the following reasons: Reviews (n = 9), sequentially published analyses (n = 5), insufficient data (n = 5), and absence of control groups in clinical trials (n = 3). In addition, 39 reports were identified from supplementary searches (websites, organizational reports, and citation tracking). After excluding 32 reports that could not be retrieved, 7 were assessed for eligibility, among which 3 were reviews and 4 lacked sufficient data. Finally, data from 9 studies met the inclusion criteria and were incorporated into the meta-analysis[15-23] (Figure 1). No additional reports were identified beyond these included studies.

Nine studies were included in this meta-analysis, comprising two RCTs and seven retrospective studies. All studies evaluated the use of regorafenib as second-line therapy in patients with advanced HCC. Sample sizes ranged from 36 to 379 in the treatment groups and from 28 to 331 in the control groups. The mean or median patient age varied from approximately 58-68 years. Most study populations were predominantly male. While regorafenib was consistently used in the treatment arms, control interventions varied and included placebo, cabozantinib, nivolumab, and best supportive care. Despite some variability in study design and comparator regimens, all included studies reported relevant clinical outcomes necessary for meta-analysis, including survival metrics and adverse event profiles (Table 1).

| Ref. | Study design | Age, years (T: C) | Sex (M/F, T: C) | Sample size (T: C) | Treatment group | Control group | Child-Pugh classification |

| Lee et al[15], 2024 | Retrospective cohort study | 63: 59 | 120/17: 45/7 | 137: 52 | Regorafenib | Nivolumab | Regorafenib group: Child-Pugh B (24.1%); nivolumab group: Child-Pugh B (42.3%) |

| Adhoute et al[16], 2022 | Retrospective, multicenter | 68: 68 | 53/5: 24/4 | 58: 28 | Regorafenib | Cabozantinib | Combined A/B proportion approximately 24%-25% |

| Casadei-Gardini et al[19], 2021 | Retrospective study | Not reported | 222/46: 264/67 | 278: 331 | Regorafenib | Cabozantinib | Not reported |

| Iavarone et al[18], 2021 | Retrospective study | 60: 61 | 27/9: 38/7 | 36: 45 | Regorafenib | BSC | Not reported |

| Kuo et al[17], 2021 | Retrospective study | 63.4 ± 10.7: 62.2 ± 10.1 | 44/14: 23/9 | 58: 32 | Regorafenib | Nivolumab | Not reported |

| Choi et al[21], 2020 | Retrospective study | 58.5 ± 9.4: 56.9 ± 10.0 | 202/21: 125/25 | 223: 150 | Regorafenib | Nivolumab | Child-Pugh A: 132 patients; Child-Pugh B: 71 patients |

| Lee et al[20], 2020 | Retrospective cohort study | 62: 61 | 83/54: 39/9 | 102: 48 | Regorafenib | Nivolumab | Not reported |

| Finn et al[22], 2018 | RCT | 64: 62 | 333/46: 171/23 | 379: 194 | Regorafenib | Placebo | Child-Pugh A only |

| Bruix et al[23], 2017 | RCT | 64: 62 | 333/46: 171/23 | 379: 194 | Regorafenib | Placebo | Child-Pugh A only |

The two RCTs were assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 tool. Both studies demonstrated a low risk of bias across most domains. However, one trial (Finn et al[22], 2018) showed a high risk of bias in the domain of allocation conceal

| Ref. | Representativeness of the exposed cohort | Selection of the non-exposed cohort | Ascertainment of exposure | Demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study | Comparability of cohorts on the basis of the design or analysis | Assessment of outcome | Was follow-up long enough | Adequacy of follow up of cohorts | Total score |

| Lee et al[15], 2024 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 8 |

| Adhoute et al[16], 2022 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 9 |

| Casadei-Gardini et al[19], 2021 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 8 | |

| Iavarone et al[18], 2021 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | 8 | |

| Kuo et al[17], 2021 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 9 |

| Choi et al[21], 2020 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 9 |

| Lee et al[20], 2020 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | 8 |

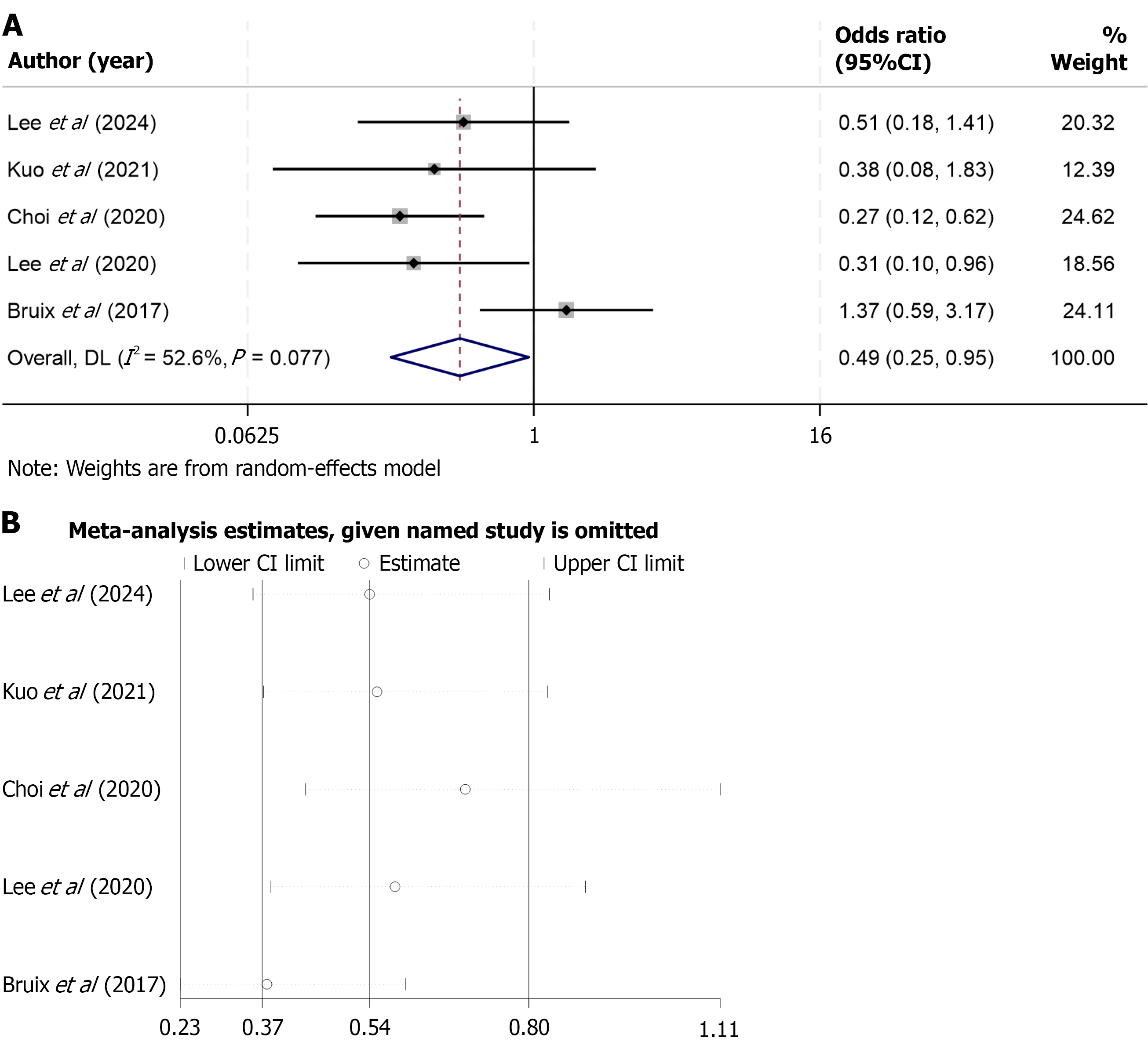

A total of seven studies reported data on OS for patients receiving regorafenib compared with control interventions. Given the presence of significant heterogeneity among the included studies (I2 = 63.2%, P = 0.012), a random-effects model was applied to pool the results. The meta-analysis demonstrated that regorafenib was associated with a significantly prolonged OS compared to the control group [WMD = 2.54; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.26-4.81; P < 0.05] (Figure 3A). To evaluate the robustness of the pooled estimate, sensitivity analysis was conducted by sequentially excluding each individual study. The results remained consistent across iterations, indicating that no single study had a disproportionate influence on the overall effect size (Figure 3B).

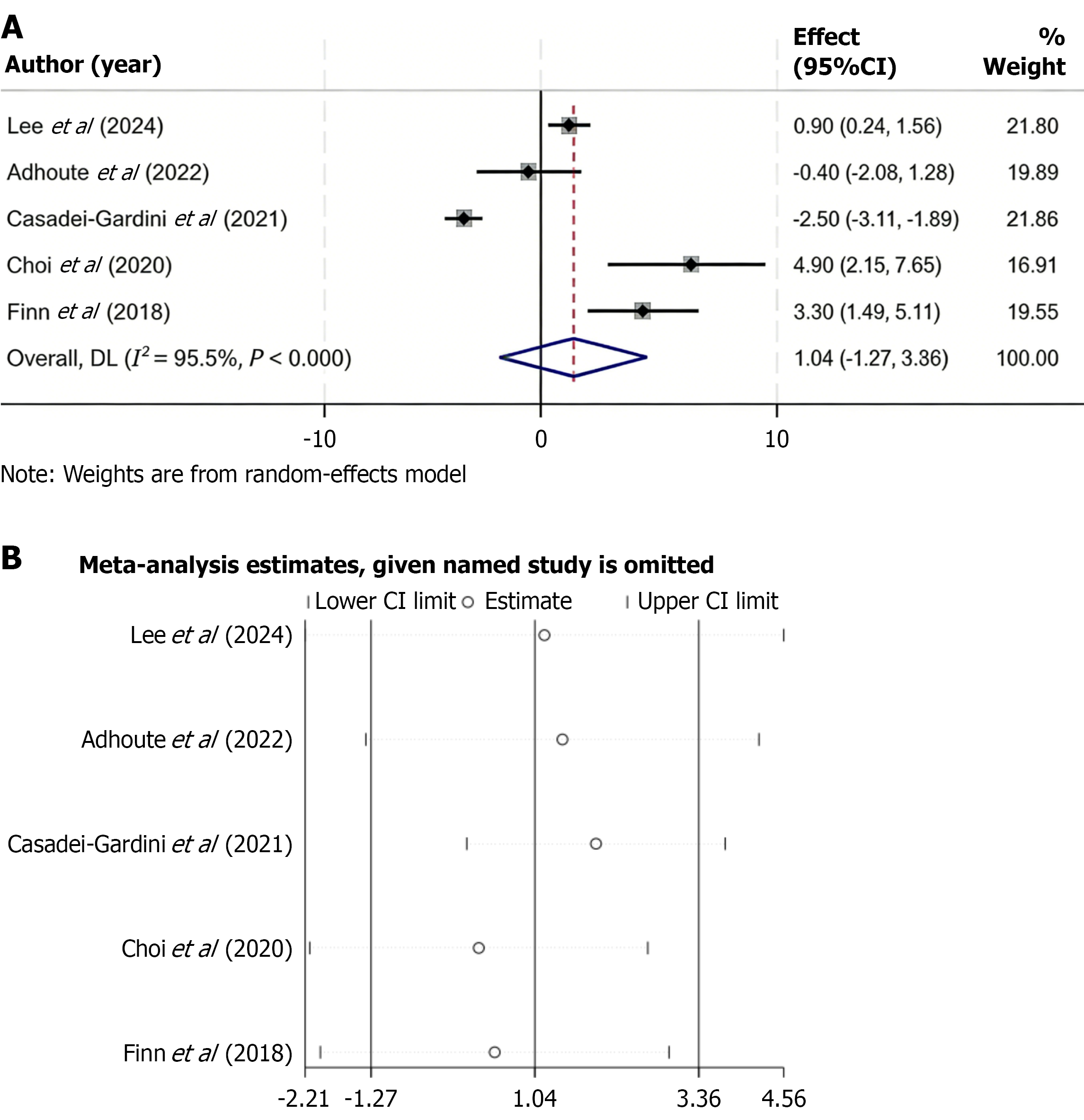

Five studies reported data on PFS in patients treated with regorafenib vs control interventions. Due to substantial heterogeneity among studies (I2 = 95.5%, P < 0.001), a random-effects model was used to pool the data. The combined results showed no significant difference in PFS between the regorafenib and control groups (WMD = 1.04; 95%CI: -1.27 to 3.36) (Figure 4A). To test the robustness of the findings, a sensitivity analysis was performed by removing each study one at a time. The overall results remained stable, indicating that no single study had a significant influence on the pooled estimate (Figure 4B).

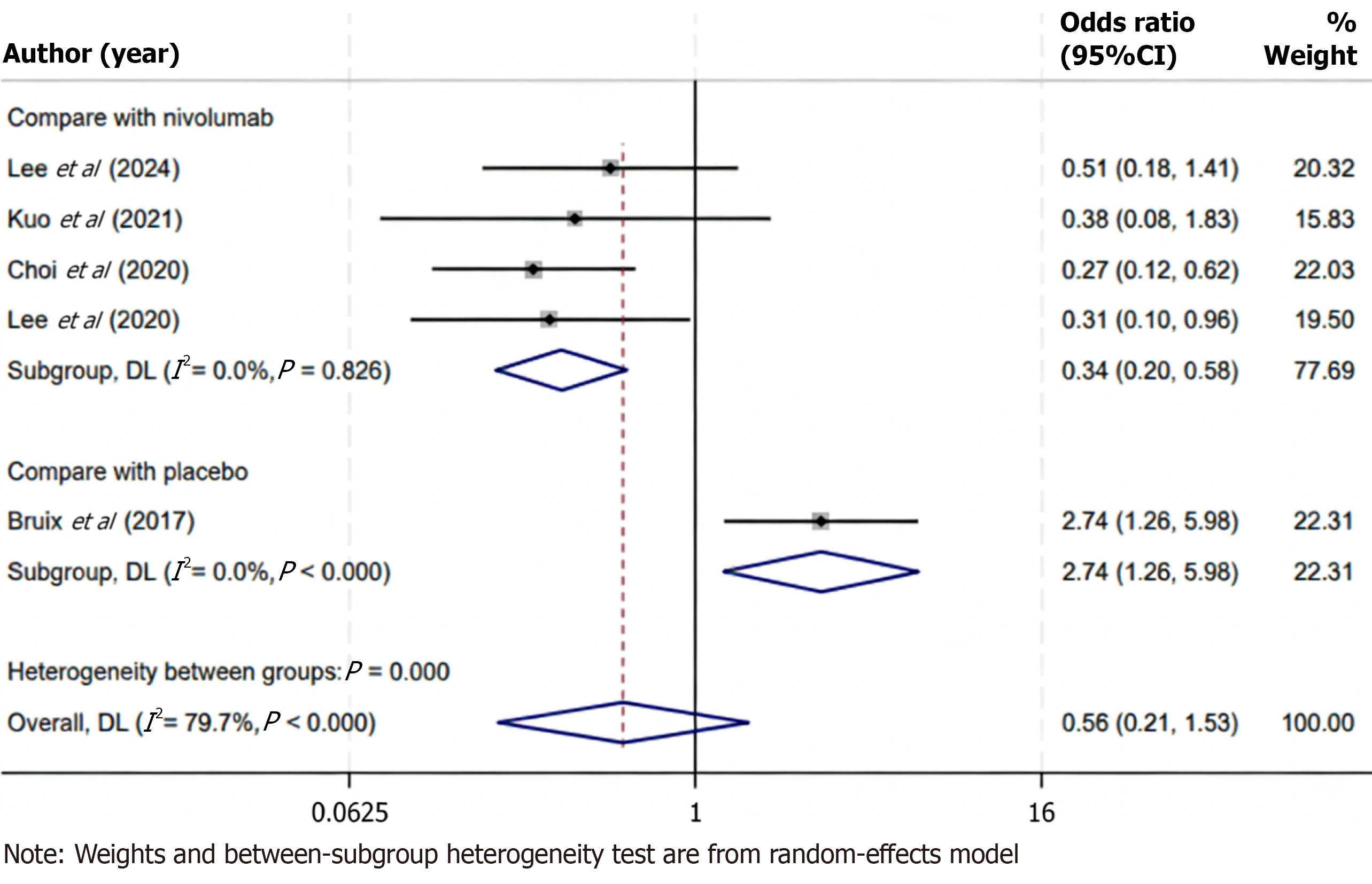

ORR data were reported in five included studies comparing regorafenib with various control therapies in patients with advanced HCC. Substantial heterogeneity was observed across studies (I2 = 79.7%, P < 0.001), warranting the use of a random-effects model for data synthesis. The pooled analysis demonstrated no statistically significant difference in ORR between the regorafenib and control groups (OR = 0.56; 95%CI: 0.21-1.53; P > 0.05), indicating that, in general, regorafenib did not achieve a higher tumor response rate compared with the control interventions assessed. To investigate potential sources of heterogeneity, a subgroup analysis was performed focusing on studies comparing regorafenib with nivolumab, an immune checkpoint inhibitor. In this subgroup, heterogeneity was not observed (I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.826), suggesting consistency among the included studies. The pooled results revealed that regorafenib was associated with a significantly lower ORR than nivolumab (OR = 0.34; 95%CI: 0.20-0.58; P < 0.05), highlighting a possible superiority of immune checkpoint blockade in eliciting objective tumor responses in this patient population (Figure 5). These findings suggest that while regorafenib may offer clinical benefit in selected contexts, its anti-tumor activity, as measured by radiographic response, may be less pronounced than that of immunotherapeutic agents such as nivolumab.

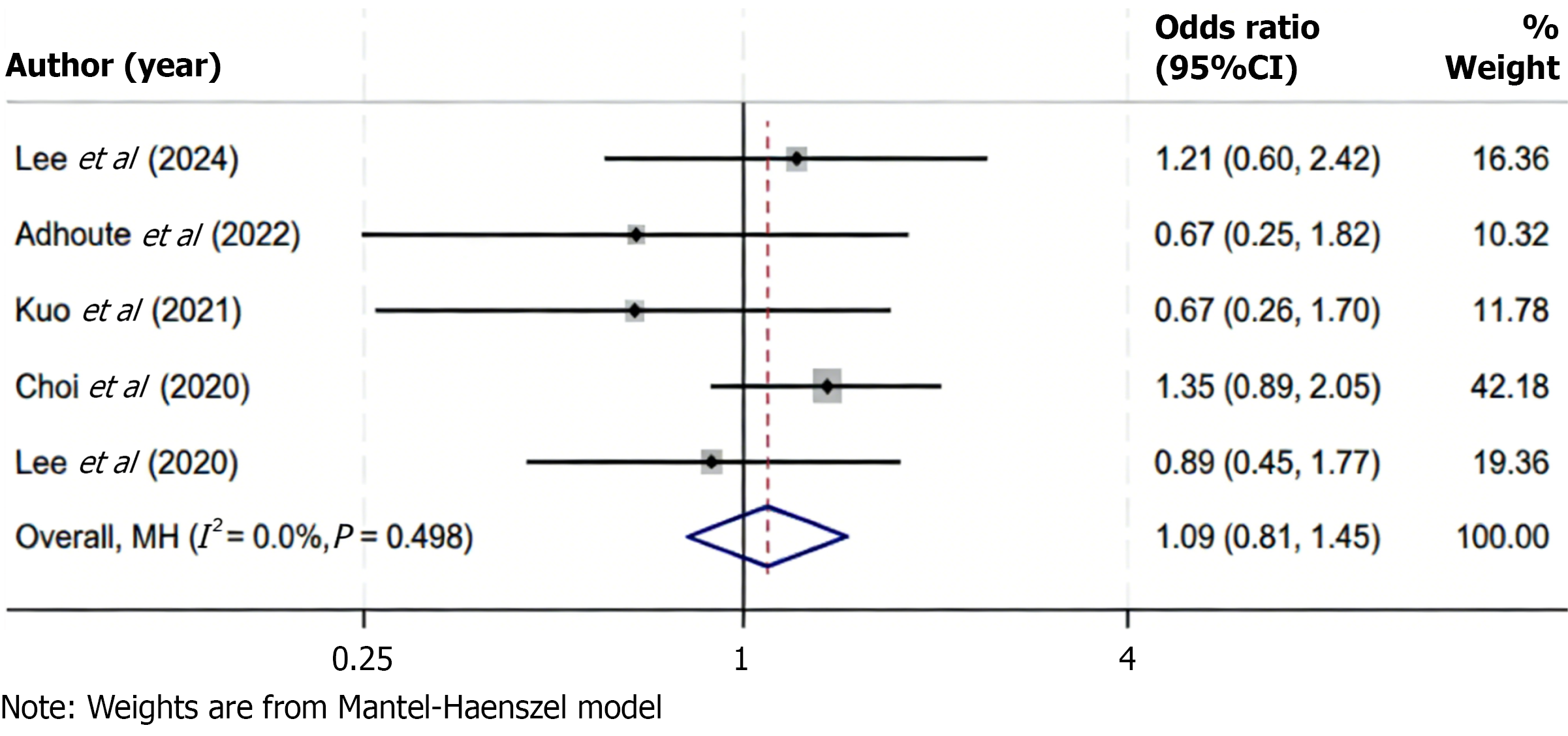

Five studies reported data on DCR among patients receiving regorafenib compared to control treatments. Statistical analysis revealed no significant heterogeneity among the included studies (I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.498), indicating consistency in the direction and magnitude of effect sizes across studies. Consequently, a fixed-effects model was applied to synthesize the data. The pooled results showed no statistically significant difference in DCR between the regorafenib and control groups (OR = 1.09; 95%CI: 0.81-1.45; P > 0.05), suggesting that the likelihood of achieving disease stabilization or partial response was comparable across treatment strategies (Figure 6). These findings indicate that regorafenib provides a similar disease control benefit as alternative therapies in the second-line setting for advanced HCC. The absence of heterogeneity supports the reliability of this conclusion across different study populations and clinical contexts.

Given that fewer than 10 studies were included in each meta-analysis, Egger’s linear regression test was applied to assess potential publication bias, as funnel plot asymmetry tests are considered less reliable with limited study numbers. The results of Egger’s test showed no statistically significant evidence of publication bias across any of the pooled analyses (P > 0.05 for all), suggesting that the meta-analytic findings were unlikely to be influenced by selective reporting.

The present meta-analysis indicates that regorafenib confers a significant survival benefit in advanced HCC patients who have failed prior therapy. Pooled results showed that regorafenib significantly improves OS compared to control treatments, with a weighted mean OS prolongation of approximately 2.5 months in favor of regorafenib (WMD = 2.54 months, 95%CI: 0.26-4.81; P < 0.05). This modest but significant improvement in OS underscores regorafenib’s efficacy in extending patient survival beyond what is achieved with placebo or other second-line options. In contrast, PFS was not significantly improved with regorafenib in the pooled analysis (WMD = 1.04 months, 95%CI: -1.27 to 3.36), suggesting that regorafenib does not substantially delay radiographic tumor progression relative to comparators. The divergence between the clear OS benefit and the minimal PFS gain may indicate that regorafenib’s survival advantage stems from factors beyond just tumor growth delay - for example, disease stabilization or post-progression outcomes - rather than dramatically prolonging the time to progression. Tumor response outcomes in this meta-analysis further highlight regorafenib’s disease-stabilizing effect[24,25]. The ORR - the proportion of patients achieving a significant tumor size reduction - was not significantly different overall between regorafenib and the pooled controls (OR = 0.56, 95%CI: 0.21-1.53; P > 0.05). This implies that regorafenib produces objective tumor responses in a comparable fraction of patients as other second-line treatments when all studies are considered together. Likewise, the DCR - which encom

Notably, subgroup analyses revealed an important nuance in treatment response. When regorafenib was specifically compared against the immune checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab, regorafenib demonstrated a significantly lower ORR (OR = 0.34, 95%CI: 0.20-0.58). This indicates that patients receiving nivolumab were substantially more likely to experience an objective tumor response than those receiving regorafenib in the second-line setting. The finding aligns with clinical expectations: Immunotherapy can induce deep and durable tumor regressions in a subset of HCC patients, whereas multi-kinase inhibitors like regorafenib more often yield stable disease. Despite this disparity in objective response, it is worth noting that disease control (including stable disease) remained high with regorafenib. Regorafenib-treated patients often achieved tumor growth stabilization, which likely contributed to the prolonged OS even though frank tumor shrinkage was less frequent compared to nivolumab[26,27].

These results are broadly consistent with trends in the literature on second-line therapies for advanced HCC and reflect known efficacy profiles of regorafenib and newer agents. The OS benefit observed with regorafenib in this analysis mirrors what has been reported in pivotal clinical trials, which established regorafenib’s role after prior treatment failure. In those trials, regorafenib demonstrated a median OS improvement of approximately 2-3 months over placebo, consistent with the pooled result in this study[23,28]. This magnitude of OS gain is comparable to that observed with other second-line targeted therapies such as cabozantinib and ramucirumab. Network meta-analyses have suggested similar efficacy between regorafenib and cabozantinib, with overlapping confidence intervals for OS and PFS[29]. The lack of significant difference in PFS in the present analysis is likely influenced by the inclusion of studies with active comparators, which naturally diminish the detectable treatment effect compared to placebo-controlled settings. Mo

Because regorafenib is approved as a second-line treatment following sorafenib failure, the inclusion of studies that enrolled patients previously treated with sorafenib, such as Finn et al[22], is consistent with current clinical practice and strengthens the external validity of the findings. Although this may introduce some degree of clinical heterogeneity, sensitivity analysis demonstrated that the exclusion of this study did not materially alter the pooled OS estimate, supporting the robustness of the results. Furthermore, the high risk of bias attributed to Finn et al[22] in the domain of allocation concealment was based on the lack of a clearly described method (e.g., central randomization or sealed envelopes). In accordance with Cochrane recommendations, unclear reporting was conservatively judged as high risk to avoid underestimating potential selection bias. However, this methodological limitation is unlikely to have influenced the overall interpretation of efficacy, given the consistent findings in sensitivity analysis.

Regorafenib is a multi-kinase inhibitor that exerts anti-tumor effects through both direct tumoricidal activity and modulation of the tumor microenvironment[34]. Specifically, it targets vascular endothelial growth factor receptor and platelet-derived growth factor receptor, key mediators of angiogenesis and stromal support. By inhibiting these signaling pathways, regorafenib suppresses neovascularization, normalizes abnormal tumor vasculature, and potentially enhances immune infiltration, thereby contributing to improved tumor control and survival outcomes[35]. The observed dis

This meta-analysis confirms that regorafenib provides a significant survival benefit as a second-line treatment for advanced HCC. Clinicians should consider regorafenib as an effective therapeutic option for patients who have failed prior systemic therapy, particularly where immune checkpoint inhibitors are not suitable. While its tumor shrinkage potential is limited compared to immunotherapy, regorafenib consistently provides disease control and survival extension, making it a reliable component of sequential systemic therapy. This study has several notable strengths. First, it includes a comprehensive analysis of multiple outcome domains, including survival, tumor response, and disease control. Sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of the primary findings, and Egger’s test showed no significant publication bias. Additionally, the inclusion of both randomized and observational studies provides a broader view of regorafenib’s real-world effectiveness. However, limitations must also be acknowledged. The number of included studies was relatively small, especially for subgroup analyses. Most studies were retrospective in design, introducing risks of selection bias and confounding. The substantial heterogeneity observed in PFS and ORR outcomes suggests underlying variability in study populations, comparators, and assessment methods. Although subgroup analysis addressed part of this variability, the findings should be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, cross-trial comparisons between regorafenib and immunotherapies are limited by the lack of head-to-head randomized trials. Lastly, with the systemic treatment landscape rapidly evolving, the applicability of these findings to patients receiving immunotherapy-based first-line treatment remains uncertain.

In conclusion, regorafenib significantly improves OS in patients with advanced HCC receiving second-line therapy, although no clear benefit was observed for PFS, response rate, or disease control. While immunotherapy may offer higher response rates, regorafenib remains a valuable treatment option.

We are grateful to everyone involved in this research.

| 1. | Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, Singal AG, Pikarsky E, Roayaie S, Lencioni R, Koike K, Zucman-Rossi J, Finn RS. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7:6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4432] [Cited by in RCA: 4440] [Article Influence: 888.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Llovet JM, Castet F, Heikenwalder M, Maini MK, Mazzaferro V, Pinato DJ, Pikarsky E, Zhu AX, Finn RS. Immunotherapies for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19:151-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 1221] [Article Influence: 305.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 3. | Haber PK, Puigvehí M, Castet F, Lourdusamy V, Montal R, Tabrizian P, Buckstein M, Kim E, Villanueva A, Schwartz M, Llovet JM. Evidence-Based Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials (2002-2020). Gastroenterology. 2021;161:879-898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 36.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | Personeni N, Pressiani T, Santoro A, Rimassa L. Regorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma: latest evidence and clinical implications. Drugs Context. 2018;7:212533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Personeni N, Pressiani T, Bozzarelli S, Rimassa L. Targeted agents for second-line treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;11:788-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kelley RK, Mollon P, Blanc JF, Daniele B, Yau T, Cheng AL, Valcheva V, Marteau F, Guerra I, Abou-Alfa GK. Comparative Efficacy of Cabozantinib and Regorafenib for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Adv Ther. 2020;37:2678-2695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cappuyns S, Corbett V, Yarchoan M, Finn RS, Llovet JM. Critical Appraisal of Guideline Recommendations on Systemic Therapies for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Review. JAMA Oncol. 2024;10:395-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 54.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kim HD, Jung S, Lim HY, Ryoo BY, Ryu MH, Chuah S, Chon HJ, Kang B, Hong JY, Lee HC, Moon DB, Kim KH, Kim TW, Tai D, Chew V, Lee JS, Finn RS, Koh JY, Yoo C. Regorafenib plus nivolumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: the phase 2 RENOBATE trial. Nat Med. 2024;30:699-707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cheng M, Tao X, Wang F, Shen N, Xu Z, Hu Y, Huang P, Luo P, He Q, Zhang Y, Yan F. Underlying mechanisms and management strategies for regorafenib-induced toxicity in hepatocellular carcinoma. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2024;20:907-922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gordan JD, Kennedy EB, Abou-Alfa GK, Beal E, Finn RS, Gade TP, Goff L, Gupta S, Guy J, Hoang HT, Iyer R, Jaiyesimi I, Jhawer M, Karippot A, Kaseb AO, Kelley RK, Kortmansky J, Leaf A, Remak WM, Sohal DPS, Taddei TH, Wilson Woods A, Yarchoan M, Rose MG. Systemic Therapy for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: ASCO Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42:1830-1850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 79.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44932] [Cited by in RCA: 51321] [Article Influence: 10264.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 12. | Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, Cates CJ, Cheng HY, Corbett MS, Eldridge SM, Emberson JR, Hernán MA, Hopewell S, Hróbjartsson A, Junqueira DR, Jüni P, Kirkham JJ, Lasserson T, Li T, McAleenan A, Reeves BC, Shepperd S, Shrier I, Stewart LA, Tilling K, White IR, Whiting PF, Higgins JPT. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6581] [Cited by in RCA: 18714] [Article Influence: 2673.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wells GA, Wells G, Shea B, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Losos WM, Tugwell P, Ga SW, Zello GA, Petersen JA. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. Proceedings of the Symposium on Systematic Reviews: Beyond the Basics; 2014 Jan 13; Manchester, United Kingdom. United Kingdom: Centre for Statistics in Medicine, University of Oxford, 2014. |

| 14. | Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5:13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4895] [Cited by in RCA: 7272] [Article Influence: 346.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Lee HJ, Lee JS, So H, Yoon JK, Choi JY, Lee HW, Kim BK, Kim SU, Park JY, Ahn SH, Kim DY. Comparison between Nivolumab and Regorafenib as Second-line Systemic Therapies after Sorafenib Failure in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Yonsei Med J. 2024;65:371-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Adhoute X, De Matharel M, Mineur L, Pénaranda G, Ouizeman D, Toullec C, Tran A, Castellani P, Rollet A, Oules V, Perrier H, Si Ahmed SN, Bourliere M, Anty R. Second-line therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with regorafenib or cabozantinib: Multicenter French clinical experience in real-life after matching. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2022;14:1510-1527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 17. | Kuo YH, Yen YH, Chen YY, Kee KM, Hung CH, Lu SN, Hu TH, Chen CH, Wang JH. Nivolumab Versus Regorafenib in Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma After Sorafenib Failure. Front Oncol. 2021;11:683341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Iavarone M, Invernizzi F, Ivanics T, Mazza S, Zavaglia C, Sanduzzi-Zamparelli M, Fraile-López M, Czauderna C, Di Costanzo G, Bhoori S, Pinter M, Manini MA, Amaddeo G, Yunquera AF, Piñero F, Blanco Rodríguez MJ, Anders M, Aballay Soteras G, Villadsen GE, Yoon PD, Cesarini L, Díaz-González Á, González-Diéguez ML, Tortora R, Weinmann A, Mazzaferro V, Romero Cristóbal M, Crespo G, Regnault H, De Giorgio M, Varela M, Prince R, Scudeller L, Donato MF, Wörns MA, Bruix J, Sapisochin G, Lampertico P, Reig M. Regorafenib Efficacy After Sorafenib in Patients With Recurrent Hepatocellular Carcinoma After Liver Transplantation: A Retrospective Study. Liver Transpl. 2021;27:1767-1778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Casadei-Gardini A, Rimassa L, Rimini M, Yoo C, Ryoo BY, Lonardi S, Masi G, Kim HD, Vivaldi C, Ryu MH, Rizzato MD, Salani F, Bang Y, Pellino A, Catanese S, Burgio V, Cascinu S, Cucchetti A. Regorafenib versus cabozantinb as second-line treatment after sorafenib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: matching-adjusted indirect comparison analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2021;147:3665-3671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lee CH, Lee YB, Kim MA, Jang H, Oh H, Kim SW, Cho EJ, Lee KH, Lee JH, Yu SJ, Yoon JH, Kim TY, Kim YJ. Effectiveness of nivolumab versus regorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma patients who failed sorafenib treatment. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2020;26:328-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Choi WM, Choi J, Lee D, Shim JH, Lim YS, Lee HC, Chung YH, Lee YS, Park SR, Ryu MH, Ryoo BY, Lee SJ, Kim KM. Regorafenib Versus Nivolumab After Sorafenib Failure: Real-World Data in Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Hepatol Commun. 2020;4:1073-1086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Finn RS, Merle P, Granito A, Huang YH, Bodoky G, Pracht M, Yokosuka O, Rosmorduc O, Gerolami R, Caparello C, Cabrera R, Chang C, Sun W, LeBerre MA, Baumhauer A, Meinhardt G, Bruix J. Outcomes of sequential treatment with sorafenib followed by regorafenib for HCC: Additional analyses from the phase III RESORCE trial. J Hepatol. 2018;69:353-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 35.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, Granito A, Huang YH, Bodoky G, Pracht M, Yokosuka O, Rosmorduc O, Breder V, Gerolami R, Masi G, Ross PJ, Song T, Bronowicki JP, Ollivier-Hourmand I, Kudo M, Cheng AL, Llovet JM, Finn RS, LeBerre MA, Baumhauer A, Meinhardt G, Han G; RESORCE Investigators. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:56-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2160] [Cited by in RCA: 2838] [Article Influence: 315.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Xu H, Cao D, Zhou D, Zhao N, Tang X, Shelat VG, Samant H, Satapathy SK, Tustumi F, Aprile G, He A, Xu X, Ge W. Baseline Albumin-Bilirubin grade as a predictor of response and outcome of regorafenib therapy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2023;23:1006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Xing R, Gao J, Cui Q, Wang Q. Strategies to Improve the Antitumor Effect of Immunotherapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front Immunol. 2021;12:783236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 27.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yang S, Zhou Y, Zeng L. Regorafenib compared to nivolumab after sorafenib failure in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2023;32:839-845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Terashima T, Yamashita T, Takata N, Takeda Y, Kido H, Iida N, Kitahara M, Shimakami T, Takatori H, Arai K, Kawaguchi K, Kitamura K, Yamashita T, Sakai Y, Mizukoshi E, Honda M, Kaneko S. Safety and efficacy of sorafenib followed by regorafenib or lenvatinib in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res. 2021;51:190-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Abou-Alfa GK, Meyer T, Cheng AL, El-Khoueiry AB, Rimassa L, Ryoo BY, Cicin I, Merle P, Chen Y, Park JW, Blanc JF, Bolondi L, Klümpen HJ, Chan SL, Zagonel V, Pressiani T, Ryu MH, Venook AP, Hessel C, Borgman-Hagey AE, Schwab G, Kelley RK. Cabozantinib in Patients with Advanced and Progressing Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:54-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1630] [Cited by in RCA: 1858] [Article Influence: 232.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 29. | Sonbol MB, Riaz IB, Naqvi SAA, Almquist DR, Mina S, Almasri J, Shah S, Almader-Douglas D, Uson Junior PLS, Mahipal A, Ma WW, Jin Z, Mody K, Starr J, Borad MJ, Ahn DH, Murad MH, Bekaii-Saab T. Systemic Therapy and Sequencing Options in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:e204930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | El-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, Crocenzi TS, Kudo M, Hsu C, Kim TY, Choo SP, Trojan J, Welling TH Rd, Meyer T, Kang YK, Yeo W, Chopra A, Anderson J, Dela Cruz C, Lang L, Neely J, Tang H, Dastani HB, Melero I. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2492-2502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3278] [Cited by in RCA: 3451] [Article Influence: 383.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 31. | Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, Kudo M, Breder V, Merle P, Kaseb AO, Li D, Verret W, Xu DZ, Hernandez S, Liu J, Huang C, Mulla S, Wang Y, Lim HY, Zhu AX, Cheng AL; IMbrave150 Investigators. Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1894-1905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2542] [Cited by in RCA: 5300] [Article Influence: 883.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (29)] |

| 32. | Yu J, Bai Y, Cui Z, Cheng C, Ladekarl M, Cheng KC, Chan KS, Yarmohammadi H, Mauriz JL, Zhang Y. Efficacy and safety of regorafenib as a first-line agent alone or in combination with an immune checkpoint inhibitor for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective cohort study. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2024;15:1072-1081. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Xu B, Lu D, Liu K, Lv W, Xiao J, Zhang X, Zhang Z, Chai J, Wang L. Efficacy and Prognostic Factors of Regorafenib in the Treatment of BCLC Stage C Hepatocellular Carcinoma After Failure of the First-Line Therapy. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2023;17:507-518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Zheng J, Wang S, Xia L, Sun Z, Chan KM, Bernards R, Qin W, Chen J, Xia Q, Jin H. Hepatocellular carcinoma: signaling pathways and therapeutic advances. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2025;10:35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 143.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 35. | Liu J, Tao H, Yuan T, Li J, Li J, Liang H, Huang Z, Zhang E. Immunomodulatory effects of regorafenib: Enhancing the efficacy of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy. Front Immunol. 2022;13:992611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/