Published online Dec 15, 2025. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v17.i12.110736

Revised: July 8, 2025

Accepted: October 17, 2025

Published online: December 15, 2025

Processing time: 181 Days and 6.3 Hours

Magnesium (Mg2+) plays a fundamental role in numerous cellular processes, including enzymatic reactions, DNA replication, oxidative stress response, and cytoskeletal dynamics. In fact, dysregulation of Mg2+ homeostasis has been increasingly associated with the development and progression of cancer, particularly colorectal cancer (CRC). Transient receptor potential melastatin (TRPM) channels, especially TRPM6 and TRPM7, are essential regulators of epithelial Mg2+ influx. While TRPM7 promotes CRC progression, the role of TRPM6 and TRPM6/

To investigate the role of membrane-localized TRPM6 and TRPM6/7 channels in Mg2+ influx, spheroid (SP) formation, stemness, and migration.

We used parental and SP-derived HT-29 cells at comparable passages as in vitro models. Mass spectrometry confirmed full-length sequences, phosphorylation, and methionine oxidation of TRPM6 and TRPM7. Mg2+ influx, total and free Mg2+ levels were measured by fluorescence imaging and biochemical assays. TRPM6 / TRPM7 expression and markers were analyzed by western blot. Func

The expression of membrane-bound TRPM6, TRPM7, and TRPM6/7 was significantly higher in SP cells than in parental cells. Mass spectrometric analysis confirmed the presence of full-length TRPM6 and TRPM7 with increased phosphorylation and oxidation in SP cells. Enhanced Mg2+ influx and total intracellular Mg2+ levels were observed in SP cells. Free ionized intracellular Mg2+ levels remained comparable across all experimental groups. Pharmacological inhibition of TRPM6 and TRPM6/7 significantly reduced Mg2+ influx, decreased total Mg2+ content, compromised CRC SP stability, abolished cancer stem-like properties, impaired cell migration, and downregulated pro-tumorigenic markers, including Nanog, cyclooxygenase-2, and matrix metalloproteinase-9.

Membrane-localized TRPM6 and TRPM6/7 channels regulate Mg2+ influx and promote CRC stemness, SP stability, and migration, highlighting their potential as therapeutic targets to inhibit CRC progression and metastasis.

Core Tip: This study demonstrated that colorectal cancer (CRC) spheroids (SPs) exhibited significantly increased membrane expression and phosphorylation of transient receptor potential melastatin (TRPM) 6 and TRPM6/7 channels, which enhanced magnesium (Mg2+) influx and promoted intracellular Mg2+ accumulation. However, selective TRPM6 and TRPM6/7 inhibitors markedly suppressed Mg2+ influx, SP formation, cell viability, and migration and impaired cancer stem-like properties. These findings highlight the critical role of TRPM6/TRPM7-mediated Mg2+ transport in CRC progression and emphasize the potential of these channels as therapeutic targets for CRC SP elimination.

- Citation: Kampuang N, Chamniansawat S, Pongkorpsakol P, Treveeravoot S, Thongon N. Transient receptor potential melastatin 6 and transient receptor potential melastatin 6/7 antagonists suppress colon adenocarcinoma HT-29 cells. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2025; 17(12): 110736

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v17/i12/110736.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v17.i12.110736

Cancer therapy has evolved from surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy to modern molecularly targeted and immunological approaches. Although advances such as targeted inhibitors, antibody drug conjugates, checkpoint blockade, and Chimeric antigen receptor T cells have improved clinical outcomes, challenges including resistance, recurrence, toxicity, and limited accessibility remain significant[1]. Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most commonly diagnosed malig

Recent evidence has implicated dysregulated magnesium (Mg2+) homeostasis in the pathogenesis of CRC. Epidemiological studies have demonstrated that low dietary Mg2+ intake is associated with increased CRC risk[5-7]. In clinical settings, hypomagnesemia has been frequently observed in patients with CRC, often secondary to targeted therapies such as cetuximab and other anti-epidermal growth factor receptor agents[8-10]. Moreover, CRC tissues exhibit increased intracellular levels of Mg2+, potentially due to enhanced sequestration and dysregulated ion transport[11]. Mechanistically, this imbalance is caused by the upregulation of Mg2+ influx channels, particularly transient receptor potential melastatin 6 and 7 (TRPM6 and TRPM7), and the concurrent downregulation of the Mg2+ efflux transporter cyclin M4[12-14]. These mechanisms cause higher intracellular Mg2+ concentrations within tumor tissues than within adjacent nonneoplastic mucosa[12], indicating that Mg2+ overload may induce tumor progression.

TRPM7 is a ubiquitously expressed channel-kinase and regulates cellular Mg2+ balance, with intracellular Mg2+ and Mg-ATP negatively regulating its activity[15-17]. TRPM6 shares similar regulatory mechanisms, although largely restricted to intestinal and renal epithelia[15,18,19]. Notably, heteromeric TRPM6/7 complexes demonstrate reduced sensitivity to intracellular inhibition, enabling sustained Mg2+ entry into epithelial cells[20,21], which may cause persistently increased intracellular Mg2+ levels in CRC cells. TRPM7 has been attributed to the progression of various cancers, including glioma; leukemia; and ocular, head and neck, esophageal, breast, lung, gastric, liver, pancreatic, colorectal, bladder, ovarian, cervical, prostate, and kidney cancers[22,23]. However, its inhibition in azoxymethane-induced CRC mice did not suppress tumor development, but instead led to systemic Mg2+ deficiency[23]. Considering its ubiquitous expression and crucial role in cellular Mg2+ homeostasis, TRPM7 antagonism may cause widespread metabolic disturbances. These findings indicate that TRPM7 is not an appropriate therapeutic target for CRC treatment, particularly because of its systemic physiological functions and the risk of inducing systemic Mg2+ deficiency. In contrast, the roles of TRPM6 and heteromeric TRPM6/7 channels in CRC progression and CSCs maintenance remain unclear.

Thus, the present study investigated the role of TRPM6 and TRPM6/7 channel inhibition in CRC using the HT-29 cell line. These cells harbor pathogenic mutations in adenomatous polyposis coli, v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha, SMAD family member 4, and tumor protein p53 and can generate CSCs-enriched spheroids (SPs) exhibiting hallmark traits of stemness, drug resistance, and high self-renewal capability[24]. Moreover, HT-29 SPs display marked resistance to 5-fluorouracil[25], underscoring their use as a robust in vitro model for evaluating novel strategies targeting CSCs and Mg2+ homeostasis in CRC.

Human colorectal adenocarcinoma HT-29 cells (ATCC HTB-38™, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, United States) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum, 1% L-glutamine, 1% nonessential amino acids, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (all from Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States). Cells were maintained under standard conditions at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Subculturing was performed in 75-cm2 tissue culture flasks (Corning Inc., NY, United States) following the American Type Culture Collection guidelines. For pharmacological modulation of Mg2+ transport, cells were treated with the following inhibitors: Co(III)hexamine (Co(III)hex; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States), a broad-spectrum Mg2+ channel blocker[26]; 2-aminoethyl diphenylborinate (2-APB; MedChemExpress, Monmouth Junction, NJ, United States), a TRPM6/7 inhibitor[21]; and Mesendogen (ME; MedChemExpress, Monmouth Junction, NJ, United States), a selective TRPM6 inhibitor[27]. A 0.3% (vol/vol) solution of dimethyl sulfoxide was used as the vehicle for inhibitor preparation and was administered to the control group to match the treatment conditions.

HT-29 cells were cultured under non-adherent, serum-free conditions using a 96-well hanging drop system (Perfecta3D®, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States) to promote SP formation. Each well was seeded with 5 × 104 cells in SP medium composed of DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 1X B27 (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States), 20 ng/mL of epidermal growth factor (PeproTech, Cranbury, NJ, United States), and 20 ng/mL of basic fibroblast growth factor (PeproTech, Cranbury, NJ, United States). To minimize evaporation, 5 mL of sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS) was added to the reservoir chamber. Cells were cultured for up to 14 days at 37 °C in an environment containing 5% CO2. Under these conditions, cells spontaneously aggregated into compact, uniformly spherical structures. Morphological assessment was conducted using inverted bright-field microscopy (Nikon ECLIPSE Ts2-FL; Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY, United States), and quantitative analysis of SP architecture, including Feret diameter, percent area, percent integrated density, and perimeter, was performed using AnaSP version 3.0[28].

To evaluate self-renewal capacity, primary SPs were enzymatically dissociated into single-cell suspensions using trypsin-EDTA (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) followed by gentle pipetting. Viable cells were quantified and re-seeded in SP medium under identical non-adherent conditions. Efficiency of sphere formation was assessed across three serial passages, with consistent seeding density and culture conditions maintained for each generation[24].

Cell viability was assessed using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. HT-29 cells were seeded into 96-well plates at 4 × 104 cells/well and incubated with MTT reagent (1 mg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States) for 3 hours at 37 °C. Formazan crystals were then solubilized in dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States), and absorbance was measured at 540 nm using a multimode plate reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, United States).

Subconfluent cells cultured in μ-Dishes (Ibidi GmbH, Gräfelfing, Germany) were preconditioned for 3 days in DMEM. On the day of measurement, the cells were washed thrice with Ca2+- and Mg2+-free Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (HiMedia Laboratories, Mumbai, India) and incubated for 1 hour in HyClone™ DMEM lacking Ca2+, Mg2+, L-glutamine, and sodium pyruvate (Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, United States) but reconstituted with 15% fetal bovine serum, 1% l-glutamine, and 1% non-essential amino acids. The cells were then loaded with 5 μmol/L Mag-Fura-2-AM (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) in N-methyl-D-glucamine buffer (145 mmol/L N-methyl-D-glucamine, 4.7 mmol/L KCl, 12 mmol/L D-glucose, 2.5 mmol/L l-glutamine, 10 mmol/L 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid; pH 7.4, 290-295 mOsm/kg H2O) for 1 hour, followed by incubation for 30 minutes in dye-free buffer to allow for complete de-esterification of acetoxymethyl esters[29]. Real-time fluorescence imaging was performed using a confocal laser scanning microscope (FV3000, Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Mg2+ influx was calculated using the following equation: ΔF/F = [F(t) - F(0)]/[F(0) - F(b)], where F(t) is the mean fluorescence intensity at a given time, F(0) is the basal fluorescence intensity, and F(b) is the background fluorescence[26]. Image analysis was conducted using ImageJ[30].

Subconfluent cells cultured in 6-well plates (Corning Inc., NY, United States) were preconditioned for 3 days in DMEM. After being washed three times with sterile PBS, the cells were incubated with a bathing solution (BS) containing (in mmol/L) 118 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.1 MgCl2, 1.25 CaCl2, 23 NaHCO3, 12 D-glucose, 2.5 l-glutamine, and 2 D-mannitol (osmolality: 290-295 mmol/kg H2O; pH 7.4)[31]. Thereafter, the cells were loaded with 5 μmol/L Mag-Fura-2-AM (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) in BS for 30 minutes at 37 °C, washed three times, and then maintained in BS for an additional 30 minutes. Fluorescence signals were acquired using a confocal laser scanning microscope (FV3000, Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Total intracellular Mg2+ levels were quantified using atomic absorption spectrophotometry (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan), following protocols previously described by Thongon[31]. Briefly, the cells were lysed by sonication, after which the resulting lysates were analyzed against a series of Mg2+ standards to determine Mg2+ concentrations.

Immunoprecipitation of TRPM6 (IP-TRPM6) was conducted as described previously[18]. Briefly, the cells were lysed in cold ratchet-integrated pneumatic actuator buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) containing 10% protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States). After centrifugation, membrane proteins were isolated using the Mem-PER™ Plus Extraction Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States). TRPM6 was immunoprecipitated using a polyclonal anti-TRPM6 antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) and Protein A/G Sepharose® beads (Abcam, Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom). Thereafter, protein complexes were incubated overnight at 4 °C, washed, and eluted with glycine-Tris buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States). The eluted samples were then concentrated using Vivaspin® 20 filters (Sartorius AG, Göttingen, Germany) for downstream applications.

Western blot analysis was performed as previously described[18]. Briefly, protein samples were denatured in sodium dodecyl sulfate buffer, separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Precision Plus Protein™ Dual Xtra Prestained Protein Standards (Cat. No. 1610377; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, United States) were used as molecular weight markers. The membranes were probed with primary antibodies targeting TRPM6 (PA5-77326; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States), TRPM7 (ab729; Abcam, Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom), matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9: Ab228402; Abcam, Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2: Ab179800; Abcam, Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom), Nanog (ab317506; Abcam, Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom), Na+/K+-ATPase (ab76020; Abcam, Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom), and β-actin (ab8226; Abcam, Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom), followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. The SuperSignal® West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) was used for detection, whereas a ChemiDoc™ Touch imaging system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, United States) was used for visualization. Densitometric analysis was performed using ImageJ.

For proteomic profiling, 20 µg of immunoprecipitated TRPM6 was reduced (100 mmol/L DTT), alkylated (100 mmol/L iodoacetamide), and digested with trypsin (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, United States). Thereafter, the peptides were dried, resuspended in 0.1% formic acid, and subjected to nano-liquid chromatography (LC) tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) using a Dionex Ultimate 3000 RSLCnano system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) coupled to a Bruker Q-ToF Compact II mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, United States). Peptide separation was performed on a PepMap100 C18 column (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) with a 90-minute acetonitrile gradient at 300 nL/minute. Spectra were then acquired in the positive ion mode and analyzed using the MASCOT engine (version 2.3, Matrix Science, London, United Kingdom) against the UniProtKB database. Quantification was based on the exponentially modified protein abundance index, and post-translational modifications were verified by MS/MS fragmentation.

HT-29 cells were seeded into 24-well plates at 5 × 105 cells/mL and grown to confluence. Afterward, a scratch wound was generated using a sterile cell scraper (Corning Inc., NY, United States), and debris was removed using sterile PBS. Wound closure was monitored over time using a bright-field microscope (Nikon ECLIPSE Ts2-FL; Nikon Instruments Inc, Melville, NY, United States), and the wound area was quantified using ImageJ software.

All data were presented as mean ± SD. Comparisons between the two groups were conducted using unpaired Student’s t-test, whereas comparisons between multiple groups were performed via one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, United States) was used for all analyses.

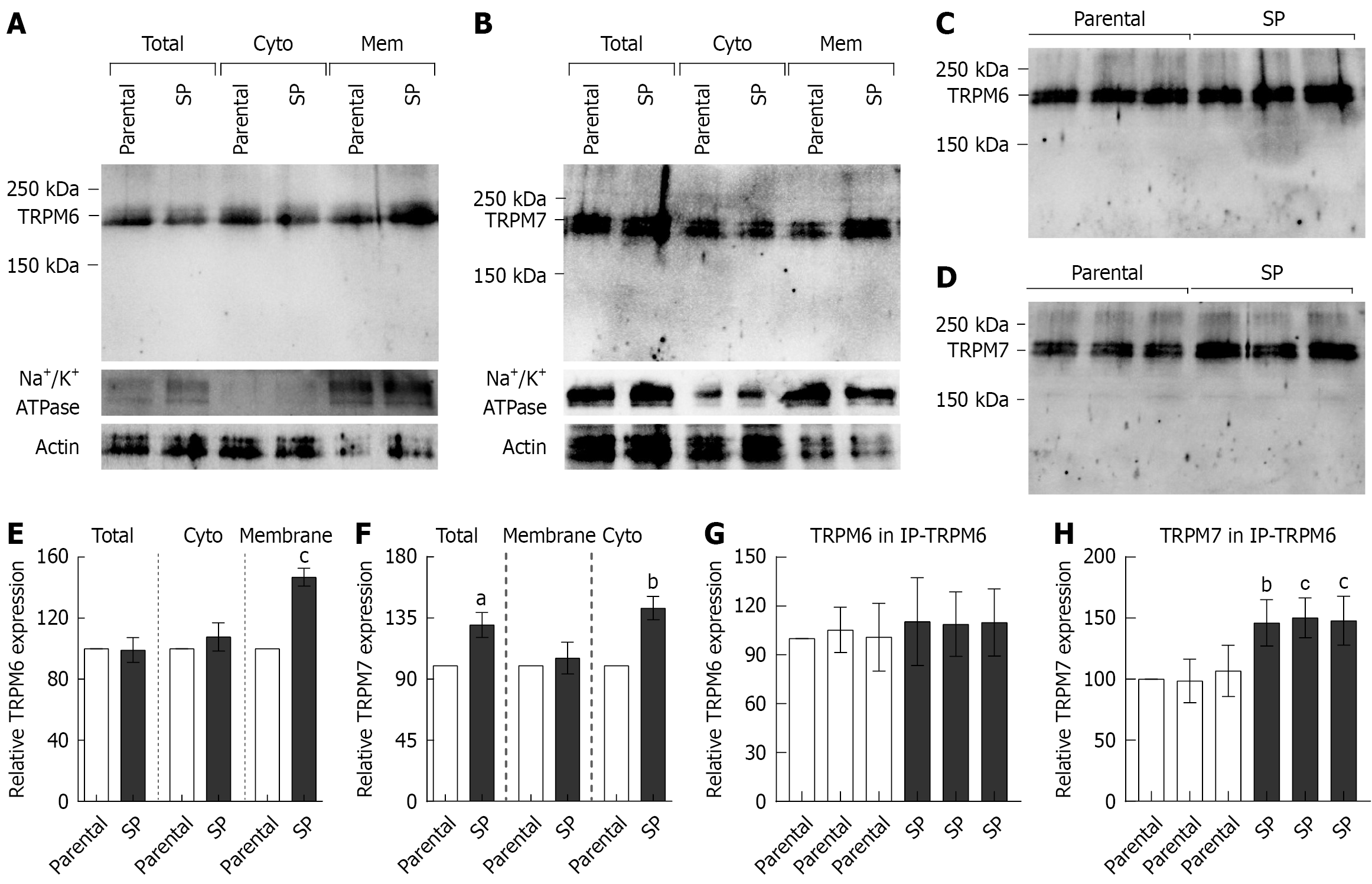

Parental HT-29 monolayers and SP-derived HT-29 cells at comparable culture passages were used. The protein ex

The membrane fractions were subjected to immunoprecipitation with a TRPM6 antibody (IP-TRPM6), followed by western blot analysis, to evaluate the expression of membrane-bound TRPM6/7 heterodimers. Figure 1C and G show that the parental and SP cells had comparable TRPM6 expression in the IP-TRPM6 membrane fractions, confirming equal protein loading. Subsequent reprobing of the same blots with a TRPM7 antibody (Figure 1D) revealed a significantly stronger TRPM7 signal in SP cells than in parental cells (Figure 1H). These findings indicate that membrane-localized TRPM6, TRPM7, and TRPM6/7 heteromeric channels are upregulated in CRC SPs.

Membrane-bound TRPM6 and TRPM7 from membranous IP-TRPM6 protein samples were further analyzed using nano-LC-MS/MS. TRPM7 protein was isolated by decreasing the TRPM6/7 heterodimer in the IP-TRPM6 protein samples. The presence of TRPM6 and TRPM7 in these samples was confirmed by protein sequence analysis. Accordingly, the TRPM6 protein sequence from parental and SP cells were 100% identical to human TRPM6 (UniProtKB: Q9BX84), and the TRPM7 protein sequence from the same groups were 100% identical to human TRPM7 (UniProtKB: Q96QT4). The exponentially modified protein abundance index values for IP-TRPM6 in the parental group were 0.10 for TRPM6 and 0.11 for TRPM7, whereas those in the SP group were 0.96 and 0.10, respectively. These indicate that sufficient and comparable amounts of TRPM6 and TRPM7 proteins were subjected to nano-LC-MS/MS analysis.

Furthermore, MS/MS fragmentation analysis was used to identify phosphorylated residues in full-length TRPM6 and TRPM7 protein sequences. A previous study reported that the S141 residue of TRPM6 regulates the localization and function of the membrane-bound TRPM6/7 heterodimer[32]. S141 residue phosphorylation in TRPM6 was detected in parental and SP cells (Table 1). TRPM6 channel permeability is induced by S1252 residue phosphorylation[33], which was observed only in SP groups. After determining the total number of phosphorylated residues in membranous TRPM6, we found that the parental and SP groups had 158 and 185 phosphorylated residues, respectively. Table 2 lists the phos

| Parental HT-29 | Spheroid-derived HT-29 | |

| N-terminus | S12, S67, S78, Y80, T87, T88, S90, T92, T94, S141, T169, T170, T176, T181, Y228, S243, S246, S274, S282, S302, T380, S386, T398, S407, Y431, S445, Y462, Y479, T481, T509, T530, S552, S558, Y574, S586, S596, T602, Y608, T635, S662, Y697, S705, T706, S743, T756, S820, Y835, Y845, T859, S869 | S12, S32, S78, Y80, T87, T88, T94, Y111, Y116, S141, S153, T169, T170, T176, T181, S184, T204, Y228, T230, S236, T239, Y259, S274, S282, T354, S362, T380, S407, S409, Y431, S445, T471, Y506, T509, Y519, Y525, Y529, T530, Y545, S551, S552, S558, Y574, S586, S590, T602, Y645, S655, Y668, S669, S705, T706, S713, S743, T759, S769, S774, S784, S789, S790, S791, S794, S796, S820, Y845, S869 (65) |

| Channels | T881, S893, T899, T936, S951, T974, S1000, S1006, Y1022, S1038, T1046, Y1053 | S876, T881, S893, S907, T913, T915, Y966, T968, T974, Y979, S1008, Y1026, Y1053 |

| TRP | Y1073, S1078, Y1086, Y1089, T1094, Y1095, S1109 | Y1073, S1078, S1080, Y1086, Y1089, Y1091, T1094, Y1095 |

| C-terminus | Y1137, S1139, Y1157, S1168, T1231, S1281, S1285, T1322, S1324, S1329, S1349, S1357, T1375, T1391, S1395, S1399, S1736, S1737, T1739, Y1741, S1746, S1747, S1986, T1993, T2011 | Y1137, S1139, Y1157, S1168, T1231, S1244, T1245, S1252, S1254, Y1273, S1277, S1281, S1285, T1311, S1332, S1339, Y1341, S1368, T1375, S1736, S1737, T1739, Y1741, S1746, S1747, S1970, Y1984, T1992, S2002, T2011, S2015 |

| Coiled coil | T1176, S1177, T1181, Y1184, S1195, S1200, S1206, T1221, S1226 | T1176, S1177, T1181, Y1184, S1195, S1200, S1206, T1221, S1226 |

| S/T rich domain | S1438, S1441, S1458, T1463, S1487, S1498, S1500, S1503, Y1533, S1539, S1541, T1577, T1598, S1603, S1616, S1618, S1623, T1628, S1630, S1633, T1635, T1647, Y1660, S1672, T1679, S1685, S1689, S1690, S1697, S1699, S1702, T1739, Y1741 | T1435, S1437, S1467, T1474, S1478, T1479, S1498, S1500, T1523, Y1533, S1539, S1541, S1562, S1563, T1577, S1583, T1589, S1605, Y1622, S1623, T1628, S1630, S1658, S1664, S1669, S1678, T1679, S1685, S1689, S1690, S1697, S1699, S1702, T1739, Y1741 |

| Dimerization motif | Y1710, S1711, S1722, T1724, T1728, Y1731 | Y1710, S1711, S1722, T1724, T1728, Y1731 |

| α-kinase domain | S1754, S1757, S1821, T1822, T1843, Y1854, Y1878, Y1880, T1895, T1897, S1908, Y1912, Y1914, T1915, T1932, S1935 | S1754, S1759, S1771, S1787, S1790, T1813, T1822, T1843, Y1854, T1855, Y1865, S1868, Y1886, S1908, Y1912, Y1914, T1915, S1944 |

| Parental HT-29 | Spheroid-derived HT-29 | |

| N-terminus | S9, T10, T12, Y18, S22, S23, T55, S57, Y62, S79, T84, S87, T89, S101, S103, Y104, Y108, S113, T115, S138, S193, S196, S233, S243, Y256, T270, Y303, T318, Y327, T332, T349, T353, S359, T379, S385, T397, S406, Y430, S453, S464, T470, Y505, T508, Y528, S539, S547, S552, S554, S561, T564, T583, Y587, T603, T615, S648, S683, T737, T739, S745, T778, S788, T807 S823, S824, S836, Y849 | S2, S9, T10, Y18, S22, S23, T55, S57, Y62, S63, S74, S79, S87, T89, Y92, S101, S103, Y108, S112, Y113, T115, S138, T166, T167, T173, S195, S196, T201, Y225, T227, S243, T252, T269, T318, T332, T353, S359, T367, T379, Y430, S438, S453, S464, T508, S539, S547, S552, S553, S554 T555, S561, T564, T583, Y587, T603, T615, S648, S661, S676, S727, S728, T778, S783, S788, T795, S799, S823, S824, S836, Y849, T860, Y863 |

| Channels | T895, Y896, S913 S921, S927, T929, S934, Y965, Y989, Y1023, S1031, Y1051, S1060, T1064, T1070, T1073, Y1080, Y1085 | T895, Y896, S913, S921, S927, S929, Y949, Y953, Y989, Y1002, S1013, Y1023, S1029, S1031, Y1041, Y1051, S1060, T1064, Y1080, Y1085 |

| TRP | Y1100, S1107, Y016, Y1122, S1036, S1040, S1141 | Y1100, S1107, Y016, Y1122, S1036, S1040, S1141 |

| C-terminus | T1154, S1155, T1163, Y1181, S1191, S12551, S1258, T1265, S1269, S1271, S1292, T1296, S1298, S12991, S13001, S1308, S13491, S1350, S13601, S1587, S1888, S1590, Y1826, T18271, S1839, S1848, T1849, T1855 | T1154, S1155, T1163, Y1181, S1191, S1193, S12551, S1258, T1265, S1269, S1271, S1292, T1296, S1298, S12991, S13001, S1308, S13491, S1350, S1357, S13601, T1580, S1587, S1588, S1590, Y1826, T18271, S1839, S1848, T1849, S1852, T1855, S1857 |

| Coiled coil | T1200, S1208, S12241, S1227, T1242, T1245, T1248, T12501 | T1200, Y1220, S12241, S1227, S1230, S1239, T1242, T12501 |

| S/T rich domain | S13861, S1389, S13901, S1394, S13951, S14031, T1404, S1406, S1409, S1412, S14161, T1418, S14451, S1455, S1463, T14661, T1470, Y1479, T1485, T14871, S14881, S14911, T1493, S14951, S14971, S15011, T15021, S15051, S15101, T1524, S1530, T1534, S15401, T1548 | S13861, S1389, S13901, S1394, S13951, S14031, T1404, S1406, S1409, S1412, S14161, T1418, Y1426, S14451, T1454, S1455, S1463, T14661, T1470, Y1479, T1485, T14871, S14881, S14911, T1493, S14951, S14971, S15011, T15021, S15051, S15101, T1524, S1530, T1534, S15401, T1548 |

| Dimerization motif | S1553, S15641, S15661 | S1553, S15641, S15661 |

| α-kinase domain | S1595, S1597, S1598, S1600, S1612, T1629, S1631, Y1642, S1656, S1657, Y1659, T1663, S16921, Y1695, Y1696, S1709, Y1727, T1738, T1740, S1749, T1756, S1776, S1785 | S1592, S1597, S1598, S1600, S1612, T1629, S1638, S1646, S1656, Y1659, T1663, T1682, S16921, Y1695, Y1696, S1709, Y1727, T1738, T1740, S1749, T1752, Y1753, Y1755, T1756, S1776, S1782, S1811 |

MS/MS fragmentation analysis further revealed widespread methionine oxidation in the full-length sequences of membrane-localized TRPM6 and TRPM7 proteins (Table 3). Notably, TRPM6 in SP and parental cells exhibited oxidation at 33 and 30 methionine residues, respectively. Similarly, TRPM7 in SP and parental cells displayed oxidation at 30 and 28 methionine residues, respectively. These findings show a modest but consistent increase in oxidative modification of TRPM channels in SP cells, potentially reflecting increased oxidative stress levels commonly associated with CRC progression[34].

| TRPM6 | TRPM7 | ||

| Parental HT-29 | Spheroid-derived HT-29 | Parental HT-29 | Spheroid-derived HT-29 |

| M33, M63, M133, M338, M370, M416, M618, M623, M625, M648, M657, M732, M768, M847, M864, M969, M984, M1020, 1061, M1076, M1093, M1162, M1278, M1183, M1434, M1436, M1575, M1879, M2020 | M1, M33, M133, M244, M338, M370, M416, M444, M450, M618, M623, M625, M648, M657, M727, M734, M739, M768, M847, M969, M984, M1093, M1162, M1190, M1265, M1434, M1436, M1575, M1719, M1879, M1904, M1947, M2020 | M43, M372, M632, M637, M649, M706, M742, M746, M782, M794, M812, M868, M878, M906 M991, M996, M1000, M1088, M1020, M1180, M1207, M1287, M1319, M1373, M1446, M1616, M1720, M1745 | M130, M575, M591, M595, M649, M662, M704, M706, M741, M746, M773, M782, M812, M868, M991, M992, M996, M1000, M1180, M1207, M1287, M1318, M1373, M1446, M1528, M1561, M1616, M1720, M1745, M1788 |

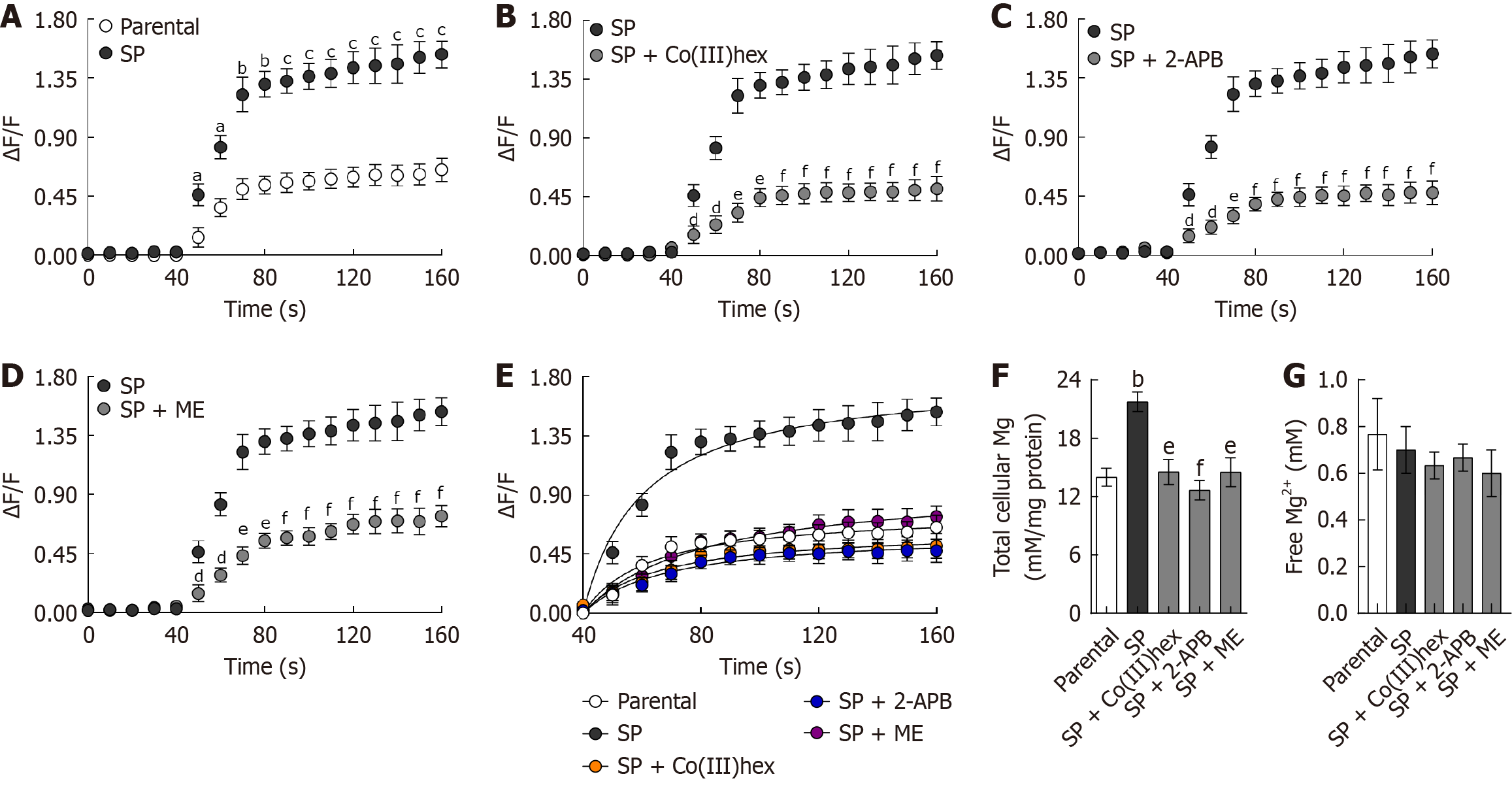

The ΔF/F fluorescence signal was measured during the first 30 seconds of the preincubation period and from 40 to 160 seconds after adding 20 mmol/L of MgSO4. Upon MgSO4 addition, the intracellular fluorescence signal in the parental HT-29 cells rapidly increased, followed by a plateau phase (Figure 2). Mg2+ influx was significantly greater in SP cells than in parental cells, consistent with the upregulation of membranous TRPM6 and TRPM7 expression. Kinetic analysis of the ΔF/F signal (40-160 seconds) using the Michaelis-Menten equation (Figure 2) revealed that the maximum reaction rate (Vmax) was significantly higher in SP cells (1.81 ± 0.09) than in parental cells (0.78 ± 0.06; P < 0.001). Furthermore, the total intracellular Mg2+ levels were significantly higher in SP cells than in parental HT-29 cells (Figure 2). However, the free ionized intracellular Mg2+ levels remained comparable across all experimental groups (Figure 2).

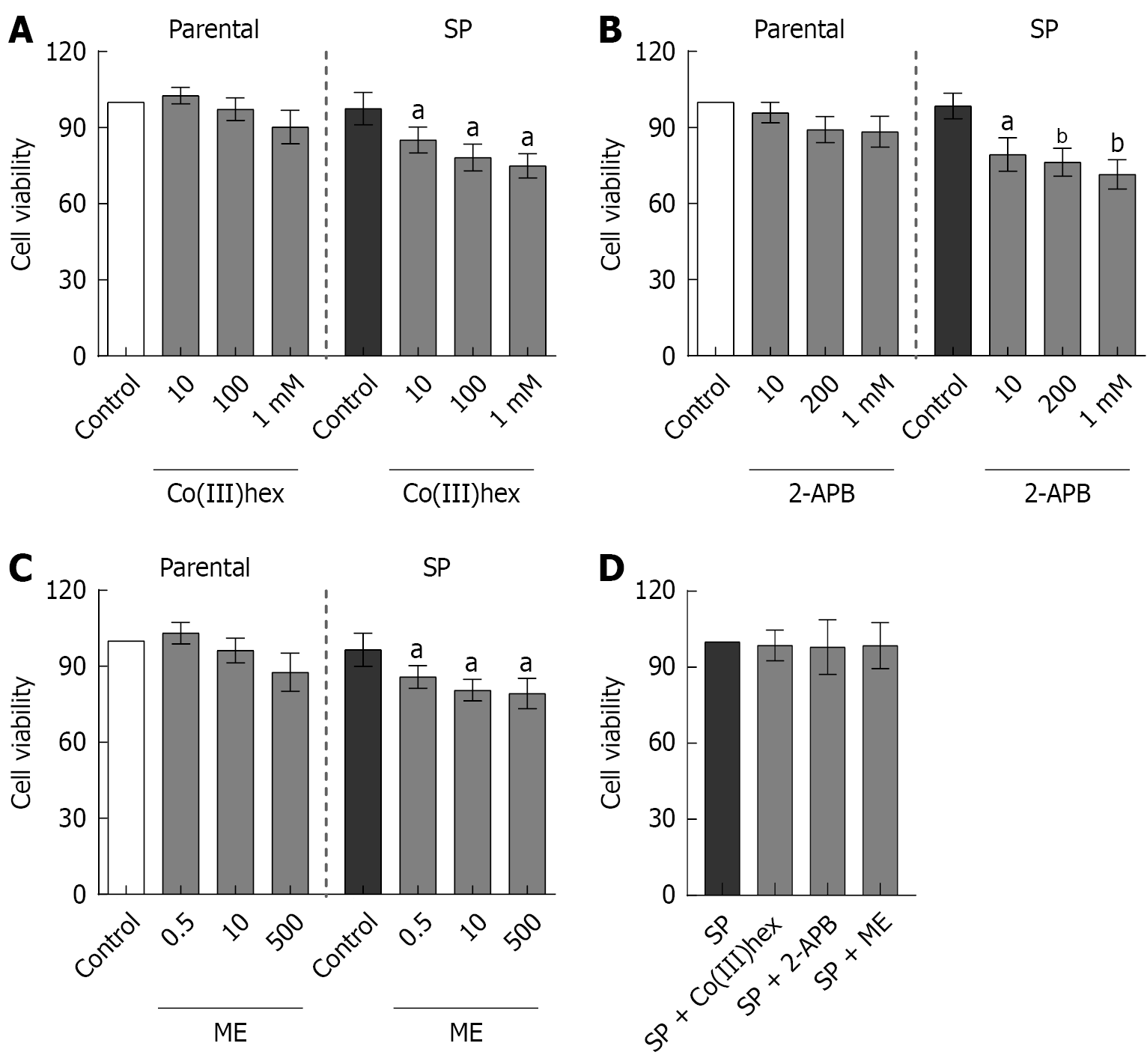

Subeffective, effective, and supra-effective concentrations of inhibitors were employed to investigate the involvement of TRPM6 and TRPM6/7 channels in enhancing Mg2+ influx and total Mg2+ content in SP cells. To this end, the effects of Co(III)hex (10 μmol/L, 100 μmol/L, and 1 mmol/L), 2-APB (10 μmol/L, 200 μmol/L, and 1 mmol/L), and ME (0.5 μmol/L, 10 μmol/L, and 500 μmol/L) on parental and SP cell viability were evaluated. After both cell types were treated for 24 hours, MTT assay analysis was performed. Co(III)hex (Figure 3A), 2-APB (Figure 3B), and ME (Figure 3C) treatment had no effect on parental HT-29 cell viability at any of the tested concentrations. In contrast, treatment with these inhibitors significantly decreased SP cell viability.

The effects of a 12-hour incubation with effective doses of Co(III)hex (100 μmol/L), 2-APB (200 μmol/L), and ME (10 μmol/L) on SP cell viability were further assessed. However, no significant decrease in SP cell viability was observed following the 12-hour treatments (Figure 3D). Mg2+ influx in SP cells was examined after the 12-hour incubation with the mentioned inhibitors. The cells treated with Co(III)hex (Figure 2), 2-APB (Figure 2), and ME (Figure 2) showed signifi

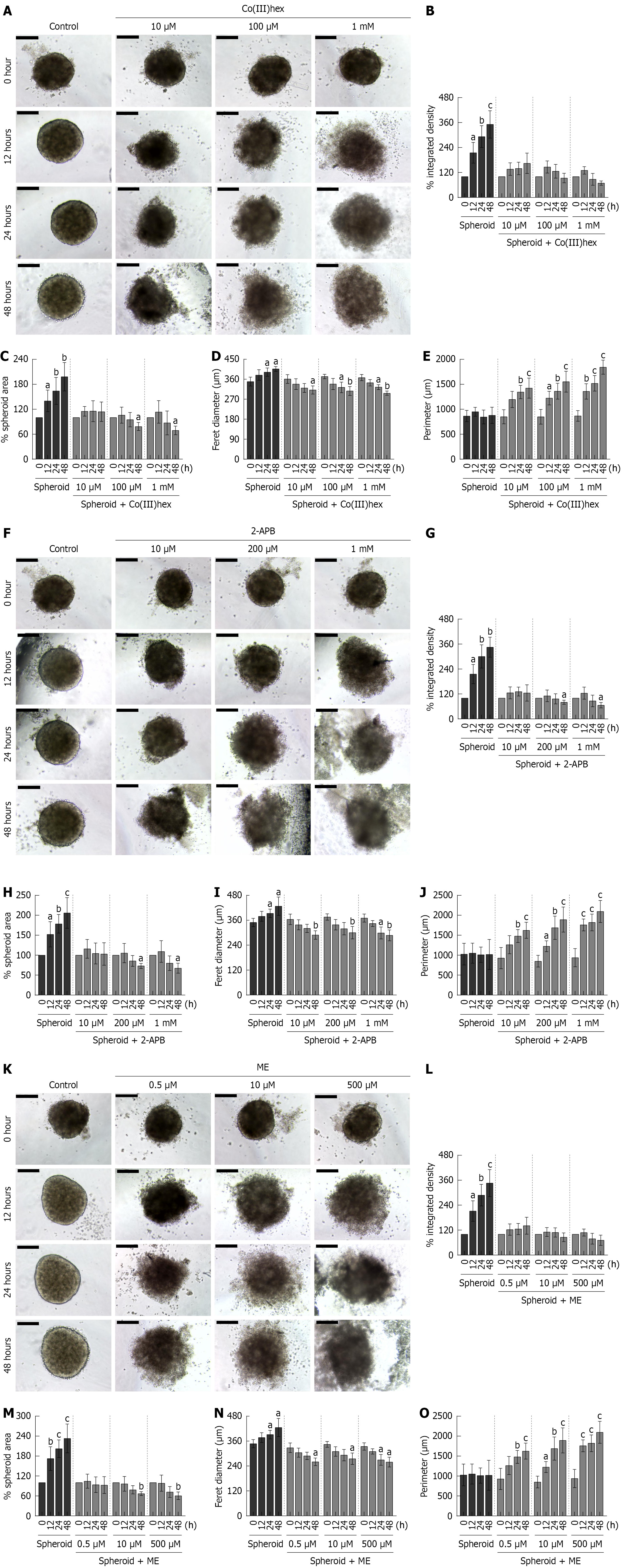

Figure 4 shows that well-defined CRC SPs were successfully generated using the hanging drop method within 14 days of seeding. HT-29 cells aggregated into compact, round SPs that progressively matured over time, with denser central core and clearly demarcated edges forming by 24 and 48 hours of culture, respectively. This morphological integrity indicates stable cancer SP formation under standard conditions. In contrast, treatment with Mg2+ channel inhibitors Co(III)hex, 2-APB, and ME markedly disrupted SP integrity. Within 12 hours of exposure to effective concentrations, the peripheral cells began to detach from the SP structure, indicating early destabilization of intercellular cohesion. After 24 hours of treatment with effective and supra-effective concentrations of Co(III)hex (Figure 4A-E), 2-APB (Figure 4F-J), or ME (Figure 4K-O), the SPs exhibited complete structural collapse, with disaggregation of the cells and loss of their spherical architecture. These demonstrate that pharmacological inhibition of TRPM6- and TRPM6/7-mediated Mg2+ influx significantly impairs the formation and maintenance of CRC SPs, emphasizing the importance of Mg2+ homeostasis regulated by TRPM channels for sustaining the structural integrity and viability of cancer SPs.

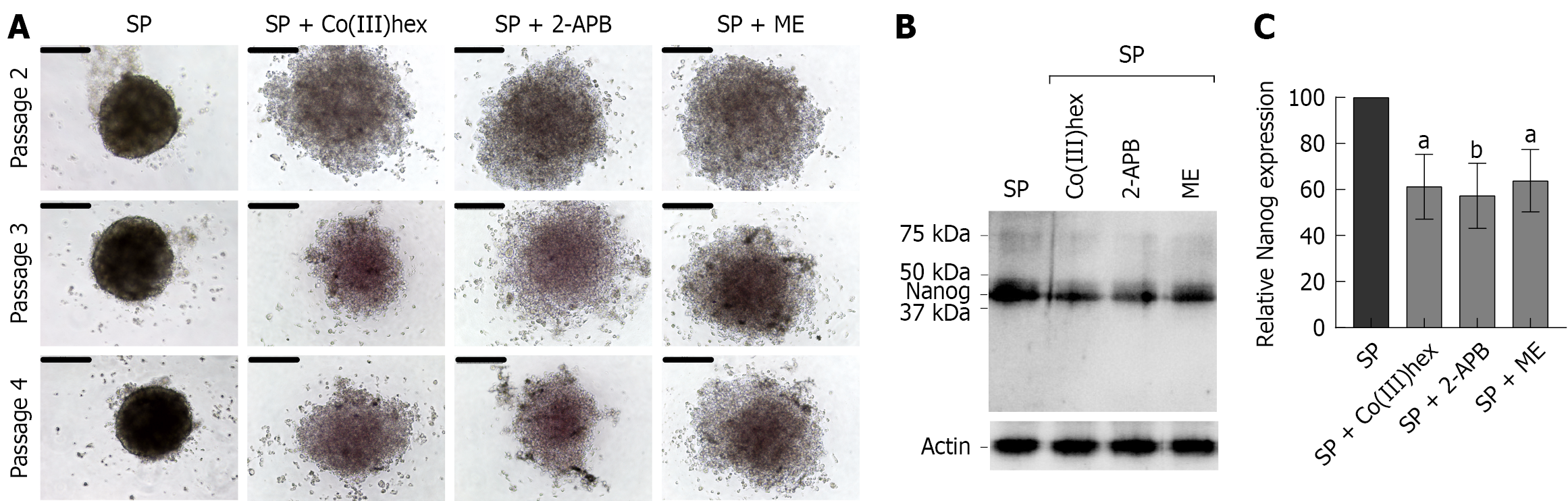

A secondary sphere formation assay was performed to evaluate the self-renewal capacity of CSCs-enriched HT-29 cancer SPs. It was found that SP cells retained the ability to form secondary SPs even after three successive subcultures (Figure 5A), confirming the CSCs-enriched characteristics of HT-29 CRC cells. Conversely, treatment with 100 μmol/L Co(III)hex, 200 μmol/L 2-APB, or 10 μmol/L ME markedly suppressed secondary SP formation over a 14-day period using the hanging drop culture system. Moreover, after assessing the expression of the CSC marker Nanog[35] (Figure 5B and C), all three inhibitors were found to significantly decrease Nanog expression in SP cells. These findings indicate that inhibiting Mg2+ influx and reducing total cellular Mg2+ levels may eliminate the CSCs-like properties of HT-29 CRC cells.

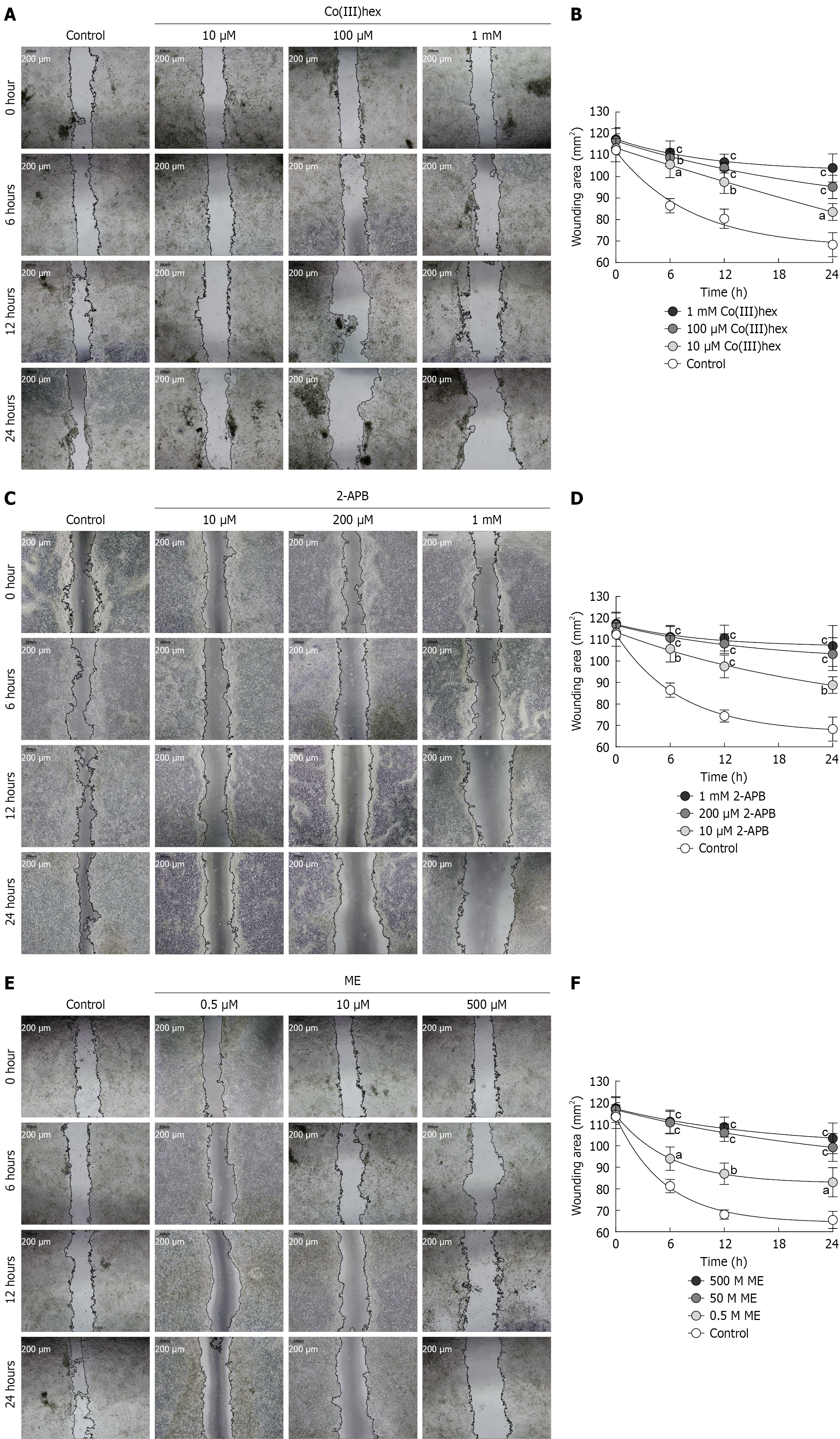

The migratory capacity of SP HT-29 cells was investigated using a two-dimensional wound-healing assay. After cell treatment using Mg2+ channel inhibitors Co(III)hex, 2-APB, or ME and monitoring for wound closure over a 6-24 hours period, all three treatment groups exhibited significantly decreased wound closure compared to the control group, as evidenced by larger remaining wound areas at each time point (Figure 6). Quantitative analysis confirmed that inhibiting Mg2+ influx promoted a sustained delay in cell migration. These findings show that Mg2+ homeostasis, which is main

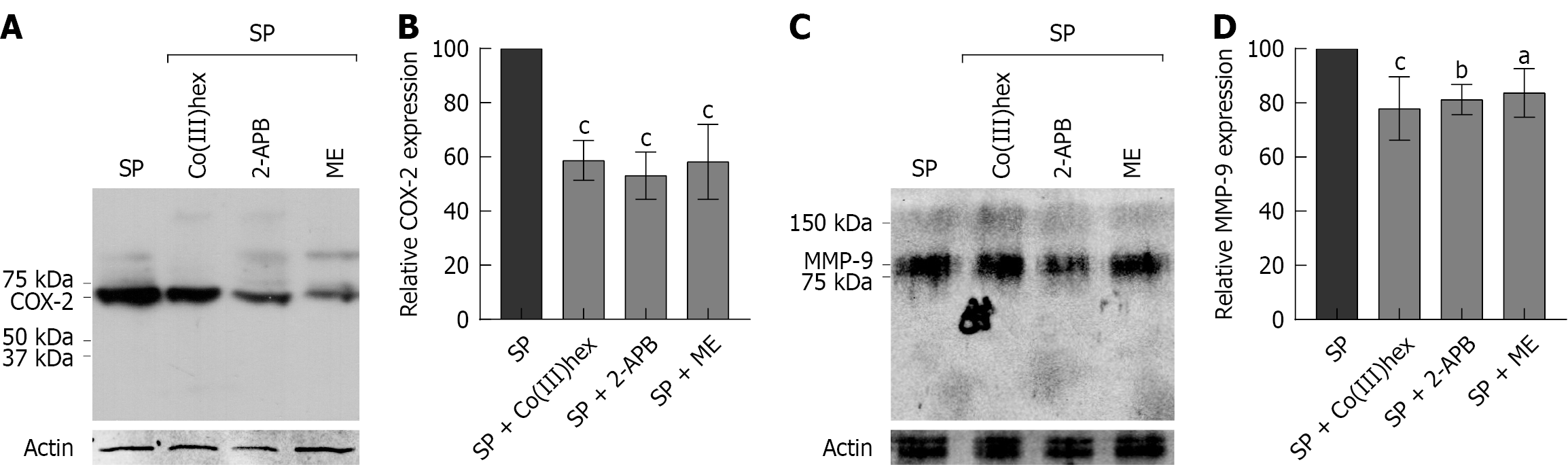

Additionally, the expression of COX-2 and MMP-9, which are well-established biomarkers of CRC, was examined[36,37]. Studies have implicated COX-2 in promoting CSCs-like activity and in contributing to apoptotic resistance, proliferation, angiogenesis, inflammation, invasion, and metastasis[38]. Similarly, evidence has shown that MMP-9 facilitates tumor progression and metastatic dissemination[37]. Figure 7 shows that COX-2 and MMP-9 were highly expressed in SP cells, indicating enhanced malignant potential. In contrast, treatment with 100 μmol/L Co(III)hex, 200 μmol/L 2-APB, or 10 μmol/L ME markedly suppressed the expression of both biomarkers. These results indicate that inhibiting Mg2+ influx via TRPM6 and TRPM6/7 channels can attenuate CRC aggressiveness by downregulating pro-tumorigenic markers, such as COX-2 and MMP-9.

The current study emphasizes the critical roles of membrane-localized TRPM6 and TRPM6/7 channels in CRC SP formation, cancer stemness, and cell migration. Our data revealed marked upregulation of membranous TRPM6, TRPM7, and heterodimer TRPM6/7 expression in SP cells, which corresponded with significantly enhanced Mg2+ influx. Moreover, kinetic analysis using the Michaelis-Menten model showed a higher Vmax in SP cells than in parental HT-29 cells, indicating an increased number of functional TRPM channels in the plasma membrane. Considering that Vmax is directly related to the number of active transporters, this finding confirms the upregulation and membrane localization of TRPM6, TRPM7, and TRPM6/7 in SP cells.

Total intracellular Mg2+ levels were also increased in SP cells, which is consistent with the findings of previous reports linking TRPM6/TRPM7 expression and Mg2+ content with CRC progression[12,13]. Although TRPM7 has been shown to regulate CRC cell proliferation and invasion[22], our findings enhance this knowledge by showing that TRPM6 and TRPM6/7 heterodimers are central mediators of SP stability and metastatic behavior. Inhibiting Mg2+ influx using Co(III)hex, 2-APB, or ME decreased intracellular Mg2+ content and impaired CRC SP formation and cell migration.

The secondary sphere formation assays confirmed that SP cells possess CSCs-like properties, as evidenced by the sustained SP-forming ability across multiple passages. Mg2+ channel inhibition disrupted this capacity and downregulated Nanog expression, a key marker of CSCs. These findings support the hypothesis that Mg2+ influx through TRPM6 and TRPM6/7 is critical for maintaining CSCs functionality, providing a novel perspective on the role of Mg2+ in tumorigenesis[4].

The specific mechanisms through which decreased Mg2+ influx and content disrupt SP formation and migration remain unclear. However, studies have well established that cancer cells exhibit high mitochondrial energy demands[39], with Mg2+ serving as a crucial cofactor in mitochondrial bioenergetics, particularly in ATP production and oxidative phos

Nano-LC-MS/MS analysis provided further insights into posttranslational modifications of membranous TRPM6 and TRPM7 proteins. Phospho-S141 on TRPM6 was detected, which is implicated in regulating TRPM6/7 heterodimerization, in both the parental and SP groups[32]. Phospho-S1252 on TRPM6, which enhances channel permeability[33], was observed specifically in SP HT-29 cells, indicating the increased Mg2+ influx observed in this group. Phospho-S138 and phospho-S1360 residues on TRPM7, known to stabilize plasma membrane localization[32,33], were identified in the parental and SP cells. Interestingly, the SP cells demonstrated hyperphosphorylation at these sites, revealing that posttranslational modifications may further enhance channel activity or membrane retention in CRC SPs. However, the functional consequences of this hyperphosphorylation on channel activity or tumorigenic behavior remain to be de

Although Mg2+ homeostasis dysregulation is well recognized in cancer[11], the relationship between Mg2+ status and colorectal carcinogenesis remains complex and controversial. A previous meta-analysis reported that insufficient and excessive dietary Mg2+ intake were associated with increased CRC risk, indicating a biphasic or U-shaped relationship between Mg2+ intake and tumorigenesis[43]. In contrast, a recent study using CRC mouse models showed that Mg2+ supplementation significantly suppressed tumor growth[44], highlighting the influence of dietary Mg2+ intake and extracellular Mg2+ levels on CRC progression. However, the present study reveals that increased total intracellular Mg2+ levels may promote CRC progression, particularly by enhancing SP stability and migratory potential. Pharmacological inhibition of the TRPM6 and TRPM6/7 channels, which mediate colonocyte Mg2+ influx, effectively decreased in

To date, direct evidence demonstrating that TRPM6 and TRPM6/7 channel inhibitors regulate pro-tumorigenic markers, such as Nanog, COX-2, and MMP-9 in CRC, is limited. However, enhanced Mg2+ influx through TRPM6 and TRPM6/7 channels potentially increases total intracellular Mg2+ levels, which may consequently activate intracellular signaling pathways, such as phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)[46,47]. Notably, the PI3K pathway has been implicated in the transcriptional regulation of various pro-oncogenic markers, including Nanog[48], COX-2[49], and MMP-9[50]. These proteins are involved in cancer stemness, inflammation, invasion, and metastasis. Although our findings indicate that TRPM6 and TRPM6/7 inhibition downregulates these markers, our hypothesized underlying molecular mechanisms, particularly Mg2+-dependent PI3K signaling involvement, require in-depth further investigation to establish a causal relationship.

The role of TRPM7 in cancer diagnosis, development, progression, invasion, treatment response, and prognosis has been comprehensively reviewed by Liu et al[22]. Owing to its ubiquitous expression and essential function in regulating intracellular Mg2+ homeostasis[15-17], systemic TRPM7 antagonism may broadly disrupt Mg2+ balance across multiple organ systems. As Mg2+ plays a critical role in various biochemical and cellular processes, its deficiency has been implicated in some pathological conditions[51]. Although TRPM7 antagonists have demonstrated potential in suppressing the progression of various cancers[22], their off-target effects on systemic Mg2+ regulation may result in significant adverse effects. For example, TRPM7 inhibition in azoxymethane-induced CRC mouse models failed to suppress tumor development, but instead led to hypomagnesemia and bone Mg2+ depletion, indicating systemic Mg2+ deficiency[23]. Approximately 50%-60% of total body Mg2+ is stored in bone; Mg2+ deficiency can contribute to osteopo

Recent perspectives highlight that effective cancer therapy requires a comprehensive strategy that targets not only tumor cells but also the supportive stromal and immune components of the tumor microenvironment[52]. Because direct tumor-focused approaches are often limited by genomic instability and therapeutic resistance, stromal and immune cells have been proposed as more stable targets capable of either promoting or restraining tumor growth. Previous studies also suggest a role for Mg2+ in regulating immune and stromal cell functions[53,54]. Nevertheless, the contribution of TRPM-mediated intracellular Mg2+ homeostasis to tumor microenvironment dynamics remains to be fully elucidated.

Recent advances in circulating tumor DNA analysis have provided highly sensitive and specific platforms for detecting oncogenic mutations in plasma. Zhang et al[55] demonstrated that programmable endonuclease-mediated cleavage can selectively enrich rare NRAS mutant fragments from a background of wild-type DNA, enabling detection at frequencies below 0.1%. This technological breakthrough underscores the potential of liquid biopsy to expand molecular diagnostics beyond tissue-based sequencing. Within this framework, TRPM6 and TRPM7 emerge as promising candidates for circulating tumor DNA-based biomarker development, given their established roles in Mg2+ homeostasis, cell proliferation, and oncogenic signaling in CRC. However, their utility in liquid biopsy applications requires further comprehensive investigation.

Recent literature on traditional medicine highlights the potential of ion channels as novel therapeutic targets in cancer. Toxin-derived compounds, such as scorpion extracts, have been shown to exert antitumor effects through ion channel regulation, underscoring the need to delineate underlying molecular mechanisms to ensure both efficacy and safety[56,57]. Clinical and mechanistic studies have further demonstrated that phytochemicals and complex herbal formulations can modulate tumor growth and treatment response[58,59]. These insights align with our findings on TRPM6 and TRPM6/7, which serve as organ-specific Mg2+ transport channels in CRC. Accordingly, traditional medicine-inspired strategies that harness ion channel modulation provide a conceptual framework for advancing TRPM6/7 as precision-oriented therapeutic targets in oncology.

TRPM6 and TRPM6/7 channels play a critical role in promoting CRC SP formation and migration. Considering that TRPM6 and TRPM6/7 channels are predominantly expressed in gastrointestinal tissues, their selective inhibition is a promising strategy for CRC treatment, which could potentially minimize systemic side effects. Nonetheless, further preclinical studies are warranted to validate these targets and explore their therapeutic potential.

We would like to express our deepest gratitude to Seelaphong P of the Microscopic Center, Faculty of Science, Burapha University and Pannengpetch S of the Center for Research and Innovation, Faculty of Medical Technology, Mahidol University for their excellent technical assistance.

| 1. | Sonkin D, Thomas A, Teicher BA. Cancer treatments: Past, present, and future. Cancer Genet. 2024;286-287:18-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in RCA: 356] [Article Influence: 178.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:229-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5690] [Cited by in RCA: 12102] [Article Influence: 6051.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 3. | Zhong C, Wang G, Guo M, Zhu N, Chen X, Yan Y, Li N, Yu W. The Role of Tumor Stem Cells in Colorectal Cancer Drug Resistance. Cancer Control. 2024;31:10732748241274196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chu X, Tian W, Ning J, Xiao G, Zhou Y, Wang Z, Zhai Z, Tanzhu G, Yang J, Zhou R. Cancer stem cells: advances in knowledge and implications for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9:170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 259] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nguyen LTD, Gunathilake M, Lee J, Oh JH, Chang HJ, Sohn DK, Shin A, Kim J. The interaction between magnesium intake, the genetic variant INSR rs1799817 and colorectal cancer risk in a Korean population: a case-control study. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2024;75:396-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Meng Y, Sun J, Yu J, Wang C, Su J. Dietary Intakes of Calcium, Iron, Magnesium, and Potassium Elements and the Risk of Colorectal Cancer: a Meta-Analysis. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2019;189:325-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Polter EJ, Onyeaghala G, Lutsey PL, Folsom AR, Joshu CE, Platz EA, Prizment AE. Prospective Association of Serum and Dietary Magnesium with Colorectal Cancer Incidence. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2019;28:1292-1299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ito D, Asano H, Kimura M, Usami E. Evaluation of the usefulness of protocol-based magnesium supplementation for hypomagnesemia in patients with advanced or recurrent colorectal cancer treated with panitumumab. Support Care Cancer. 2025;33:472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Schulz C, Heinemann V, Heinrich K, Haas M, Holch JW, Fraccaroli A, Held S, von Einem JC, Modest DP, Fischer von Weikersthal L, Kullmann F, Moehler M, Scheithauer W, Jung A, Stintzing S. Predictive and prognostic value of magnesium serum level in FOLFIRI plus cetuximab or bevacizumab treated patients with stage IV colorectal cancer: results from the FIRE-3 (AIO KRK-0306) study. Anticancer Drugs. 2020;31:856-865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hoshida T, Tanabe K, Tsubaki M, Nagai N, Nishida S. Comparison of Side Effects of Anti-epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (Anti-EGFR) Antibody Drugs During Initial Induction and Reinduction in Colorectal Cancer: A Case Series. Cureus. 2025;17:e87184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Trapani V, Wolf FI. Dysregulation of Mg(2+) homeostasis contributes to acquisition of cancer hallmarks. Cell Calcium. 2019;83:102078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Schiroli D, Marraccini C, Zanetti E, Ragazzi M, Gianoncelli A, Quartieri E, Gasparini E, Iotti S, Baricchi R, Merolle L. Imbalance of Mg Homeostasis as a Potential Biomarker in Colon Cancer. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11:727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pugliese D, Armuzzi A, Castri F, Benvenuto R, Mangoni A, Guidi L, Gasbarrini A, Rapaccini GL, Wolf FI, Trapani V. TRPM7 is overexpressed in human IBD-related and sporadic colorectal cancer and correlates with tumor grade. Dig Liver Dis. 2020;52:1188-1194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Funato Y, Yamazaki D, Mizukami S, Du L, Kikuchi K, Miki H. Membrane protein CNNM4-dependent Mg2+ efflux suppresses tumor progression. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:5398-5410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Fonfria E, Murdock PR, Cusdin FS, Benham CD, Kelsell RE, McNulty S. Tissue distribution profiles of the human TRPM cation channel family. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2006;26:159-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 287] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Penner R, Fleig A. The Mg2+ and Mg(2+)-nucleotide-regulated channel-kinase TRPM7. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2007;313-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Nadler MJ, Hermosura MC, Inabe K, Perraud AL, Zhu Q, Stokes AJ, Kurosaki T, Kinet JP, Penner R, Scharenberg AM, Fleig A. LTRPC7 is a Mg.ATP-regulated divalent cation channel required for cell viability. Nature. 2001;411:590-595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 722] [Cited by in RCA: 756] [Article Influence: 30.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kampuang N, Thongon N. Mass spectrometric analysis of TRPM6 and TRPM7 from small intestine of omeprazole-induced hypomagnesemic rats. Front Oncol. 2022;12:947899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 19. | Voets T, Nilius B, Hoefs S, van der Kemp AW, Droogmans G, Bindels RJ, Hoenderop JG. TRPM6 forms the Mg2+ influx channel involved in intestinal and renal Mg2+ absorption. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 457] [Cited by in RCA: 434] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhang Z, Yu H, Huang J, Faouzi M, Schmitz C, Penner R, Fleig A. The TRPM6 kinase domain determines the Mg·ATP sensitivity of TRPM7/M6 heteromeric ion channels. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:5217-5227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ferioli S, Zierler S, Zaißerer J, Schredelseker J, Gudermann T, Chubanov V. TRPM6 and TRPM7 differentially contribute to the relief of heteromeric TRPM6/7 channels from inhibition by cytosolic Mg(2+) and Mg·ATP. Sci Rep. 2017;7:8806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Liu H, Dilger JP, Lin J. A pan-cancer-bioinformatic-based literature review of TRPM7 in cancers. Pharmacol Ther. 2022;240:108302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Huang J, Furuya H, Faouzi M, Zhang Z, Monteilh-Zoller M, Kawabata KG, Horgen FD, Kawamori T, Penner R, Fleig A. Inhibition of TRPM7 suppresses cell proliferation of colon adenocarcinoma in vitro and induces hypomagnesemia in vivo without affecting azoxymethane-induced early colon cancer in mice. Cell Commun Signal. 2017;15:30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gheytanchi E, Naseri M, Karimi-Busheri F, Atyabi F, Mirsharif ES, Bozorgmehr M, Ghods R, Madjd Z. Morphological and molecular characteristics of spheroid formation in HT-29 and Caco-2 colorectal cancer cell lines. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21:204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Virgone-Carlotta A, Lemasson M, Mertani HC, Diaz JJ, Monnier S, Dehoux T, Delanoë-Ayari H, Rivière C, Rieu JP. In-depth phenotypic characterization of multicellular tumor spheroids: Effects of 5-Fluorouracil. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0188100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wolf FI, Trapani V, Simonacci M, Mastrototaro L, Cittadini A, Schweigel M. Modulation of TRPM6 and Na(+)/Mg(2+) exchange in mammary epithelial cells in response to variations of magnesium availability. J Cell Physiol. 2010;222:374-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Geng Y, Feng B. Mesendogen, a novel inhibitor of TRPM6, promotes mesoderm and definitive endoderm differentiation of human embryonic stem cells through alteration of magnesium homeostasis. Heliyon. 2015;1:e00046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Piccinini F. AnaSP: a software suite for automatic image analysis of multicellular spheroids. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2015;119:43-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Robinson KM, Janes MS, Pehar M, Monette JS, Ross MF, Hagen TM, Murphy MP, Beckman JS. Selective fluorescent imaging of superoxide in vivo using ethidium-based probes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15038-15043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 670] [Cited by in RCA: 652] [Article Influence: 32.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:671-675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34536] [Cited by in RCA: 39911] [Article Influence: 2850.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Thongon N, Penguy J, Kulwong S, Khongmueang K, Thongma M. Omeprazole suppressed plasma magnesium level and duodenal magnesium absorption in male Sprague-Dawley rats. Pflugers Arch. 2016;468:1809-1821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 32. | Blanchard MG, Kittikulsuth W, Nair AV, de Baaij JH, Latta F, Genzen JR, Kohan DE, Bindels RJ, Hoenderop JG. Regulation of Mg2+ Reabsorption and Transient Receptor Potential Melastatin Type 6 Activity by cAMP Signaling. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:804-813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Cai N, Lou L, Al-Saadi N, Tetteh S, Runnels LW. The kinase activity of the channel-kinase protein TRPM7 regulates stability and localization of the TRPM7 channel in polarized epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:11491-11504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Bahria K, Slama N, Abdellatif A, Benachour K. Moderate NADH supplementation prevents early colon carcinogenesis by modulating inflammation and oxidative stress in a mouse model. J Mol Histol. 2025;56:333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Vasefifar P, Motafakkerazad R, Maleki LA, Najafi S, Ghrobaninezhad F, Najafzadeh B, Alemohammad H, Amini M, Baghbanzadeh A, Baradaran B. Nanog, as a key cancer stem cell marker in tumor progression. Gene. 2022;827:146448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Mehmood T, Nasir Q, Younis I, Muanprasat C. Inhibition of Mitochondrial Dynamics by Mitochondrial Division Inhibitor-1 Suppresses Cell Migration and Metastatic Markers in Colorectal Cancer HCT116 Cells. J Exp Pharmacol. 2025;17:143-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Peng L, Zhang X, Zhang ML, Jiang T, Zhang PJ. Diagnostic value of matrix metalloproteinases 2, 7 and 9 in urine for early detection of colorectal cancer. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2023;15:931-939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Hashemi Goradel N, Najafi M, Salehi E, Farhood B, Mortezaee K. Cyclooxygenase-2 in cancer: A review. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:5683-5699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in RCA: 556] [Article Influence: 69.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Li L, Pan D, Ai R, Zhou Y. Mitochondria-Associated Pathways in Cancer and Precancerous Conditions: Mechanistic Insights. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26:8537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Frasch WD. The participation of metals in the mechanism of the F(1)-ATPase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1458:310-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Maier JA. Magnesium and Cell Cycle. In: Kretsinger RH, Uversky VN, Permyakov EA. Encyclopedia of Metalloproteins. New York: Springer, 2013: 1343-1348. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 42. | Matthews HK, Bertoli C, de Bruin RAM. Cell cycle control in cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2022;23:74-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 490] [Cited by in RCA: 932] [Article Influence: 233.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 43. | Qu X, Jin F, Hao Y, Zhu Z, Li H, Tang T, Dai K. Nonlinear association between magnesium intake and the risk of colorectal cancer. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:309-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Li H, Feng X, Li H, Ma S, Song W, Yang B, Jiang T, Yang C. The Supplement of Magnesium Element to Inhibit Colorectal Tumor Cells. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2023;201:2895-2903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Castiglioni S, Cazzaniga A, Trapani V, Cappadone C, Farruggia G, Merolle L, Wolf FI, Iotti S, Maier JAM. Magnesium homeostasis in colon carcinoma LoVo cells sensitive or resistant to doxorubicin. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Weng Y, Jian Y, Huang W, Xie Z, Zhou Y, Pei X. Alkaline earth metals for osteogenic scaffolds: From mechanisms to applications. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2023;111:1447-1474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Jiang H. Metal Transporters in Neurodegeneration. In: Biometals in Neurodegenerative Diseases. MA, United States: Academic Press, 2017: 313-347. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 48. | Storm MP, Bone HK, Beck CG, Bourillot PY, Schreiber V, Damiano T, Nelson A, Savatier P, Welham MJ. Regulation of Nanog expression by phosphoinositide 3-kinase-dependent signaling in murine embryonic stem cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:6265-6273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Yang J, Wang X, Gao Y, Fang C, Ye F, Huang B, Li L. Inhibition of PI3K-AKT Signaling Blocks PGE(2)-Induced COX-2 Expression in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2020;13:8197-8208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Mao Y, Su C, Yang H, Ma X, Zhao F, Qu B, Yang Y, Hou X, Zhao B, Cui Y. PI3K/AKT/mTORC1 signalling pathway regulates MMP9 gene activation via transcription factor NF-κB in mammary epithelial cells of dairy cows. Anim Biotechnol. 2024;35:2314100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | de Baaij JH, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ. Magnesium in man: implications for health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2015;95:1-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 771] [Cited by in RCA: 1084] [Article Influence: 98.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Liu H, Dilger JP. Different strategies for cancer treatment: Targeting cancer cells or their neighbors? Chin J Cancer Res. 2025;37:289-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Sadikan MZ, Lambuk L, Hairi HA, Mohamud R. Molecular Impact of Magnesium-Mediated Immune Regulation in Diseases. Scientifica (Cairo). 2025;2025:4211238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Wang Z, Liu Q, Liu C, Tan W, Tang M, Zhou X, Sun T, Deng Y. Mg(2+) in β-TCP/Mg-Zn composite enhances the differentiation of human bone marrow stromal cells into osteoblasts through MAPK-regulated Runx2/Osx. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235:5182-5191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Zhang Z, Ji Q, Zhang Z, Lyu B, Li P, Zhang L, Chen K, Fang M, Song J. Ultra-sensitive detection of melanoma NRAS mutant ctDNA based on programmable endonucleases. Cancer Genet. 2025;294-295:47-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Hengrui L. Toxic medicine used in Traditional Chinese Medicine for cancer treatment: are ion channels involved? J Tradit Chin Med. 2022;42:1019-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Hengrui L. An example of toxic medicine used in Traditional Chinese Medicine for cancer treatment. J Tradit Chin Med. 2023;43:209-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Liu HR. Effect of Traditional Medicine on Clinical Cancer. Biomed J Sci Technol Res. 2020;30:23548-23551. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Liu HR. Harnessing traditional medicine and biomarker-driven approaches to counteract Trichostatin A-induced esophageal cancer progression. World J Gastroenterol. 2025;31:106443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |