Published online Nov 15, 2025. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v17.i11.112203

Revised: August 27, 2025

Accepted: October 17, 2025

Published online: November 15, 2025

Processing time: 116 Days and 14.7 Hours

Pancreatic carcinoma is recognized as one of the most prothrombotic malig

We report a patient who presented with ARI as the initial manifestation prior to the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. The 50-year-old male was admitted to our emergency department with sharp, left-sided abdominal pain and was subse

This case illustrates that arterial thromboembolism, when diagnosed at an ad

Core Tip: We describe a 50-year-old male patient who presented with acute renal infarction as the initial manifestation prior to the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Given its low incidence and nonspecific clinical symptoms, diagnostic suspicion and prompt initial intervention are crucial for achieving a favorable clinical prognosis.

- Citation: Wang QY, Xia WH, Wan W, Liu JP. Pancreatic cancer initially presenting with acute renal infarction: A case report. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2025; 17(11): 112203

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v17/i11/112203.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v17.i11.112203

It has been established that pancreatic carcinoma is characterized by a systemic cancer-induced hypercoagulable state, which poses a high risk of developing thromboembolic complications[1,2]. The prothrombotic malignancy enables to express tissue factor, to release neutrophil extracellular traps, and to disseminate tumor-derived micro-vesicles. These procoagulant factors and other potential mechanisms collectively contribute to coagulation, platelet aggregation and endothelial function impairment, resulting in thrombotic events[3,4].

Traditionally, the main consideration of thrombotic events has been given to venous thromboembolism (VTE) in patients with pancreatic cancer, which commonly encompasses deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. However, arterial thromboembolic (ATE) events are yet a neglected field[3]. ATEs are relatively uncommon in patients with pancreatic cancer, with an estimated incidence of 2%-6%[5,6]. A retrospective matched-cohort analysis published in 2017 identified 12279 patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma between 2002 and 2011[7]. The cumulative risk of ATE at 6 months was 5.9% (95%CI: 5.5-6.4) compared to 2.4% (95%CI: 2.1-2.7) in the control cohort (P < 0.001), which indicates that patients newly diagnosed with pancreatic cancer faced a considerably increased short-term incidence of developing ATE. Embolism has been commonly recognized as a life-threatening complication of cancer, with poor prognosis. The events predominantly manifest as myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular, diseases that are hardly incidental due to their grave clinical consequences. ATEs involving other sites, including mesenteric and iliofemoral artery thrombosis, have also been sporadically reported[8].

Nevertheless, pancreatic cancer presenting with acute renal infarction (ARI) as the first manifestation is rarely seen but occurs occasionally, and its early diagnosis remains a challenge. Herein, we present a Chinese patient presenting with acute abdomen, subsequently diagnosed with ARI, which served as the initial clinical manifestation of pancreatic cancer.

A previously healthy 50-year-old male presented to the emergency department with sudden severe left-sided abdominal pain.

Left-sided abdominal pain manifested upon awakening and progressively intensified, persisting for approximately 12 hours. The pain was aggravated when the patient was in the supine position but could be relieved when the patient maintained the anterior tilt position. There was no tenderness or rebound pain in the abdomen during physical exami

The patient was previously in good health. No significant past medical history.

The patient had a significant history of long-term tobacco use (approximately one pack per day for more than 30 years, with a smoking index of 600). He had no family history of malignancies, psychological or genetic disorders.

His vital signs remained within normal limits. No icteric discoloration was observed on the skin or sclera. Further physical examination revealed tenderness upon percussion in the right renal area. McBurney’s point tenderness and Murphy’s sign were both negative.

Blood tests revealed D-dimer levels of 18.14 mg/L (reference range: 0-0.5 mg/L) and fibrinogen degradation products at 65.8 μg/mL (reference range: 0-5 μg/mL). Serum tumor marker analysis showed CA199 at 36418 U/mL (reference range: < 30 U/mL), CA125 at 3058 U/mL (reference range: 0-24 U/mL), and CEA at 75.77 ng/mL (reference range: 0-5 ng/mL). Blood biochemistry results indicated a urea level of 7.8 mmol/L (reference range: 3.1-8 mmol/L) and creatinine level of 102 μmol/L (reference range: 57-97 μmol/L). Bilirubin, alanine aminotransferase, and aspartate aminotransferase levels were within the normal reference ranges.

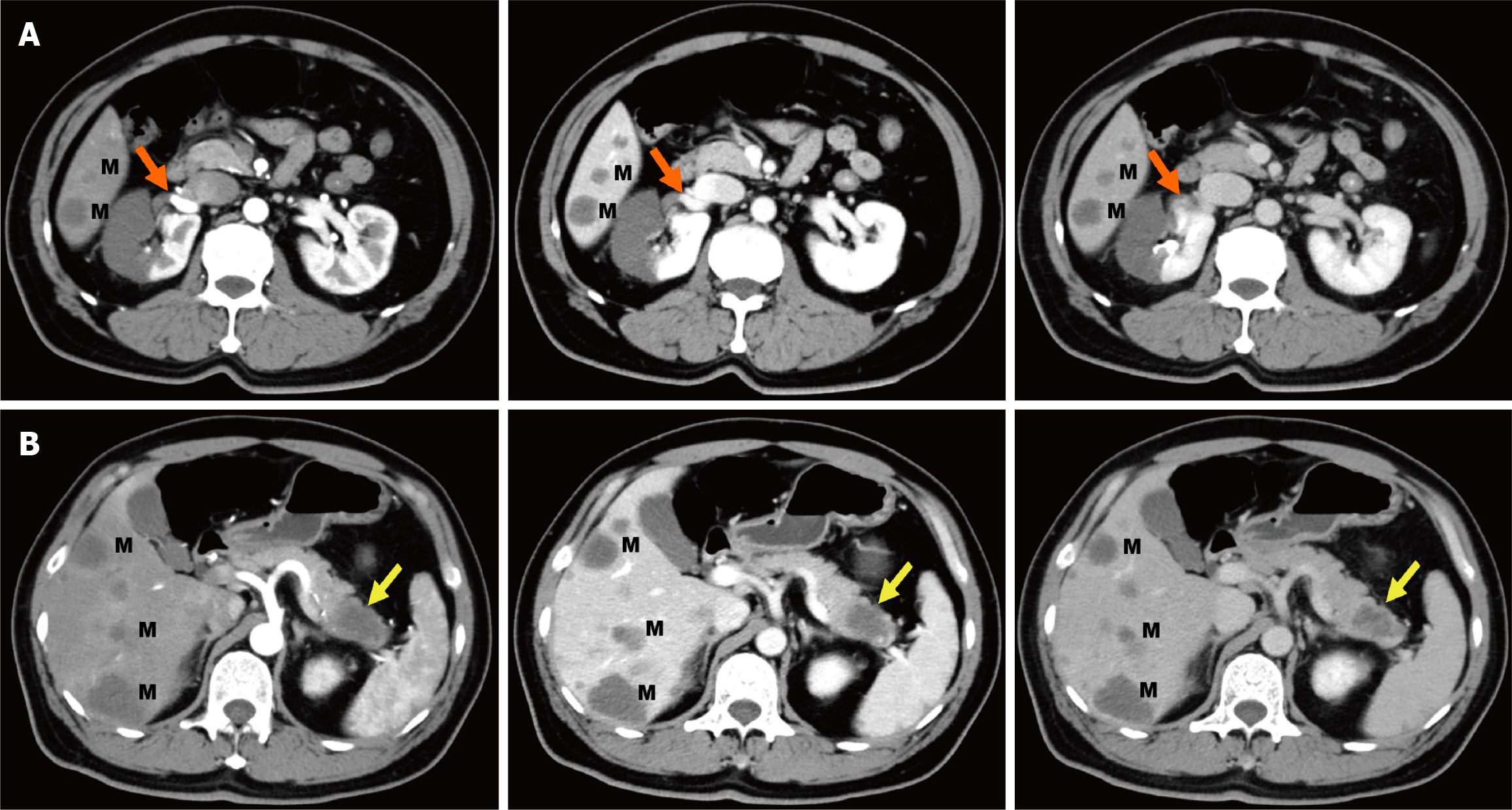

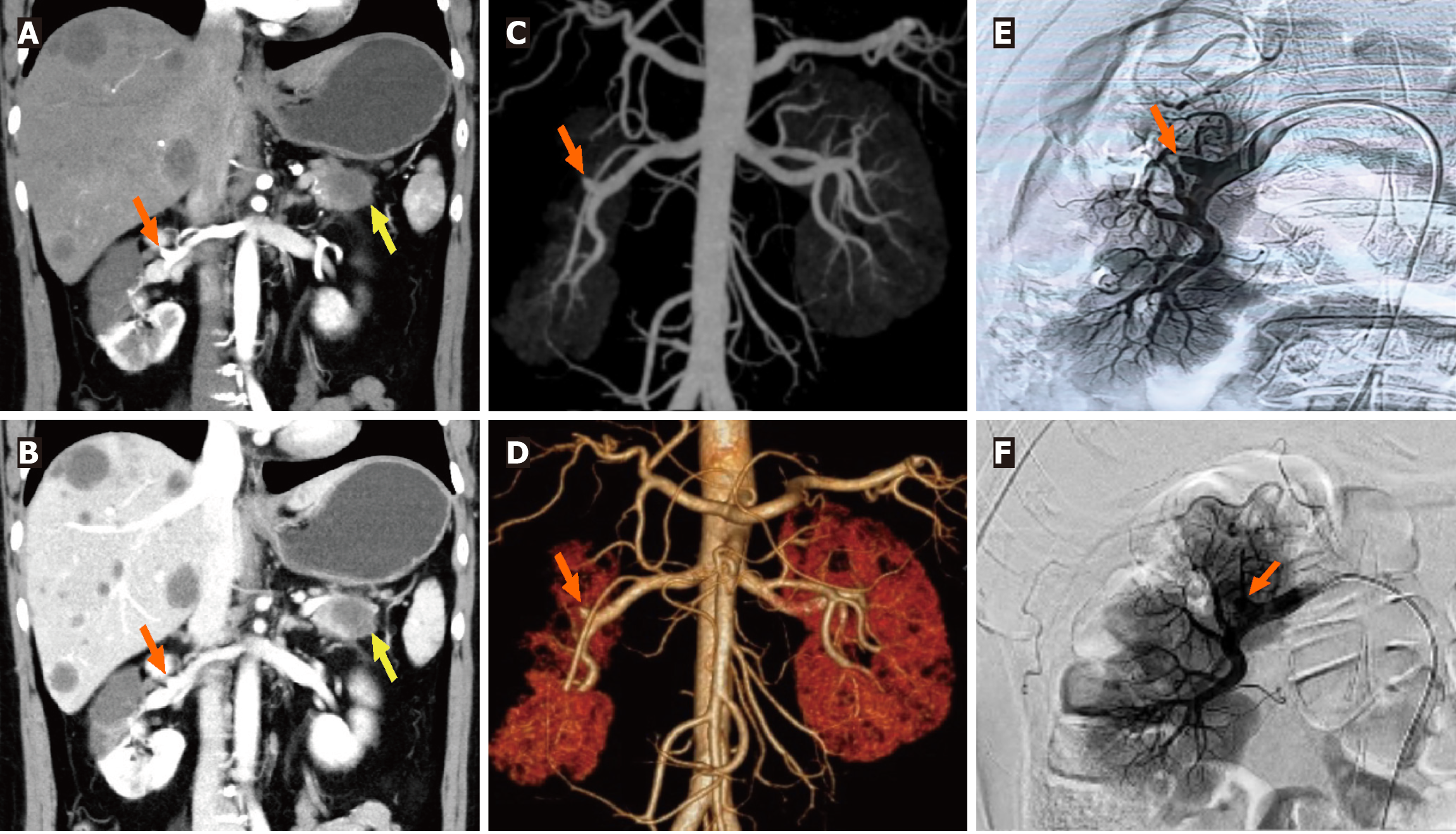

Combined with the discrepancy between the self-symptom and objective signs, we speculated on the possibility of thrombotic diseases and performed total abdominal CT angiography (CTA) and enhanced CT. The mesenteric artery CTA scan showed no significant abnormalities. However, a filling defect was visible in the anterior branch of the right renal artery, suggesting embolus formation, and the right kidney was abnormally enhanced (Figures 1A and 2A-D). Therefore, right renal infarction was diagnosed. Meanwhile, the abdominal CT suggested a soft tissue mass, approximately 4.0 cm × 2.6 cm in size, at the pancreatic tail with a poorly defined boundary, uneven internal density and liquefaction necrosis. On the enhanced scan, the lesion showed mild uneven enhancement, with a slightly high-density shadow in the sur

Based on the rapid onset of severe left-sided abdominal pain and imaging findings revealing a filling defect in the right renal artery, a diagnosis of ARI was made. The radiological findings further strongly supported the diagnosis of pan

Right renal artery angiography was promptly performed. Under high-pressure angiography, the blood flow in the upper and middle branches of the right renal artery was occluded, while the lower branch was well visualized (Figure 2E). Subsequently, intravascular thrombolysis with urokinase was administered. An indwelling contrast catheter was placed postoperatively to allow for intermittent infusion of urokinase and standard heparin over 24 hours. The patient reported relief from abdominal pain (Figure 2F). Following this, we transitioned to subcutaneous administration of low-molecular-weight heparin for anticoagulation. Rechecked D-dimer level was 5.79 mg/L.

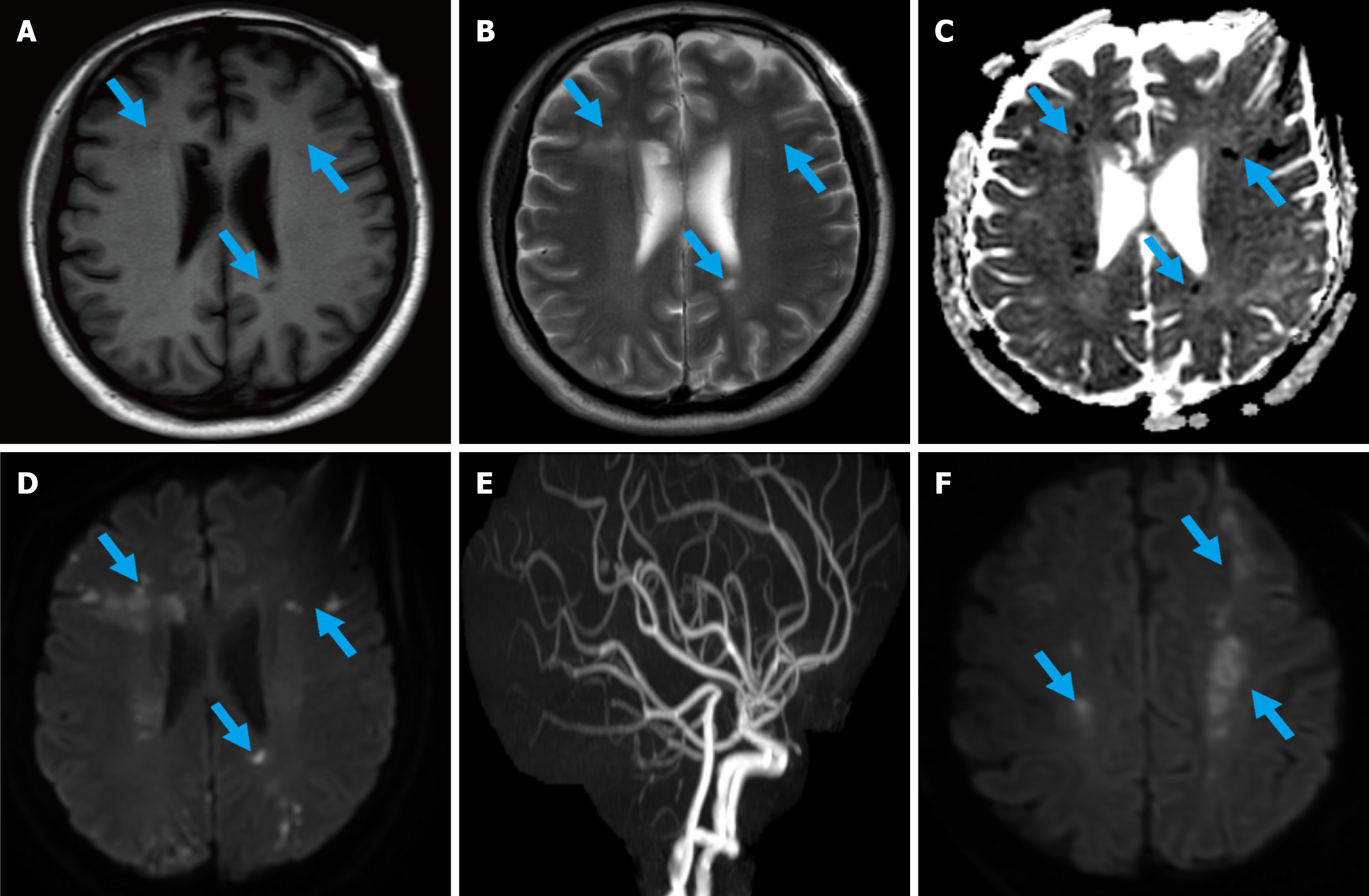

We aimed to perform an ultrasound-guided liver or pancreatic biopsy for pathological diagnosis. However, within just two days, the patient developed disorientation, characterized by impaired awareness of the surrounding environment. Magnetic resonance imaging plain scan showed scattered patchy long T1 and long T2 signals in the bilateral lateral ventricles, centrum semiovale and frontoparietal lobes, with high signal on diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) and low signal on apparent diffusion coefficient mapping (Figure 3A-D). Acute cerebral infarction was considered. However, cerebral magnetic resonance angiography showed no significant cerebrovascular stenosis, and the multiple intracranial infarcts could not be explained by the vascular distribution (Figure 3E). Thus, Trousseau syndrome was considered. Only one day later, the patient developed mixed aphasia, central facial paralysis, and right limb weakness. Repeat DWI revealed new infarcts in the bilateral parietal and frontal lobes (Figure 3F). The patient's performance status deteriorated rapidly during this period and only supportive treatment was allowed, with an extremely poor prognosis under pa

Patients with pancreatic carcinoma are characterized by a very high risk of thromboembolic disease, a common complication that is causally caused by a tumor-driven procoagulant property. The main clinical consideration of this hypercoagulability has been given to VTE in this population. ATE events tend to present with acute arterial occlusion in specific organs, probably resulting in fatal embolization. The events are usually demonstrated at autopsy, which would certainly tend to underestimate the real incidence. These events mentioned in autopsy studies and several case reports leave challenges in exploring the epidemiology and pathogenesis. Herein, we report a patient with pancreatic cancer presenting ARI as the first sign of the occult malignancy. Our study highlights the marked rarity of acute renal artery occlusion associated with pancreatic cancer and underscores the severity of this complication, which represents a preterminal event.

There is a partial overlap in risk factors for arterial and venous thromboses. It is believed that the generation of a local and systemic hypercoagulable state could confer a growth advantage to tumor cells covered by thrombi, in favor of escaping immune arrestment and promoting growth of metastases. As per the available literature on pancreatic cancer, an episode of ATE correlates with an advanced tumor stage, with a 6-month cumulative incidence of 2.3% at stage 0 compared with 7.7% at stage 4[5]. A retrospective cohort study including 17 patients with pancreatic cancer observed that the time of stroke event always occurs at a metastatic stage[10]. In addition, previous studies have conclusively linked an increased risk of thrombus in association with tumor site in the pancreatic body and tail. In a cohort of patients with pancreatic cancer (n = 202), individuals with a tumor located at corpus/cauda had a 2-fold increased risk compared with those with a tumor located at caput[11]. We made similar observations in this report. Plausible mechanisms for this phenomenon are that tumors of the body and tail are generally larger and more often metastasize at the time of first diagnosis due to delayed specific symptom presentation[12]. More importantly, pancreatic body/tail cancer is associated with the poorly differentiated, molecular squamous subtype and inflammation gene programs, rendering aggressive tumor biology[12,13]. Furthermore, mucinous cystic neoplasms are common in the body or tail. Existing evidence indi

The key to the quick diagnosis of ARI lies in enhanced CT, and invasive renal arteriography is pursued as the gold standard for diagnosis. The overall diagnostic and treatment strategies aim to restore TIMI grade 3 blood flow without delay. For ATE, platelet activation appears to be crucial for the development of arterial thrombosis according to Virchow’s triad[18]. However, we must acknowledge that this point was neglected in the therapeutic process. It is worth considering whether both antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy combinations will attenuate the thrombosis risk and potentially improve long-term outcomes. Furthermore, prior studies pointed out that ATE in pancreatic cancer may be caused by cardiogenic emboli from nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis or to thrombosis in situ[10]. However, in our study, the patient's condition progressed so rapidly that the source of the thrombus could not be identified without permission for autopsy. In addition, our study was necessarily limited in that a diagnosis with pathology and molecular biology is lacking, which would partly provide evidence to further determine the pathogenesis mechanism and to investigate therapeutic methods and optimal prophylaxis.

In summary, we depicted a patient with pancreatic cancer manifesting ARI as the first presentation with a worse outcome, which appears to be a terminal or preterminal event in patients whose disease is initially too far advanced to have any real prognostic value or therapeutic opportunities. To some extent, our report may help raise awareness and promote investigation into prophylactic strategies aimed at preventing this severe complication.

We appreciate the support from doctors and patients.

| 1. | Khorana AA, Fine RL. Pancreatic cancer and thromboembolic disease. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:655-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Campello E, Ilich A, Simioni P, Key NS. The relationship between pancreatic cancer and hypercoagulability: a comprehensive review on epidemiological and biological issues. Br J Cancer. 2019;121:359-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Aronson D, Brenner B. Arterial thrombosis and cancer. Thromb Res. 2018;164 Suppl 1:S23-S28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Campello E, Bosch F, Simion C, Spiezia L, Simioni P. Mechanisms of thrombosis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2022;35:101346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Navi BB, Reiner AS, Kamel H, Iadecola C, Okin PM, Elkind MSV, Panageas KS, DeAngelis LM. Risk of Arterial Thromboembolism in Patients With Cancer. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:926-938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 309] [Cited by in RCA: 505] [Article Influence: 56.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tuzovic M, Herrmann J, Iliescu C, Marmagkiolis K, Ziaeian B, Yang EH. Arterial Thrombosis in Patients with Cancer. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2018;20:40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Epstein AS, Soff GA, Capanu M, Crosbie C, Shah MA, Kelsen DP, Denton B, Gardos S, O'Reilly EM. Analysis of incidence and clinical outcomes in patients with thromboembolic events and invasive exocrine pancreatic cancer. Cancer. 2012;118:3053-3061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Schattner A, Klepfish A, Huszar M, Shani A. Two patients with arterial thromboembolism among 311 patients with adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Am J Med Sci. 2002;324:335-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bao L, Zhang S, Gong X, Cui G. Trousseau Syndrome Related Cerebral Infarction: Clinical Manifestations, Laboratory Findings and Radiological Features. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020;29:104891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bonnerot M, Humbertjean L, Mione G, Lacour JC, Derelle AL, Sanchez JC, Riou-Comte N, Richard S. Cerebral ischemic events in patients with pancreatic cancer: A retrospective cohort study of 17 patients and a literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e4009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Blom JW, Osanto S, Rosendaal FR. High risk of venous thrombosis in patients with pancreatic cancer: a cohort study of 202 patients. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:410-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Birnbaum DJ, Bertucci F, Finetti P, Birnbaum D, Mamessier E. Head and Body/Tail Pancreatic Carcinomas Are Not the Same Tumors. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11:497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Li D, Pise MN, Overman MJ, Liu C, Tang H, Vadhan-Raj S, Abbruzzese JL. ABO non-O type as a risk factor for thrombosis in patients with pancreatic cancer. Cancer Med. 2015;4:1651-1658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wakabayashi M, Kikuchi Y, Yamaguchi K, Matsuda T. Prognosis of pancreatic cancer with Trousseau syndrome: a systematic review of case reports in Japanese literature. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2023;35:40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Woei-A-Jin FJ, Tesselaar ME, Garcia Rodriguez P, Romijn FP, Bertina RM, Osanto S. Tissue factor-bearing microparticles and CA19.9: two players in pancreatic cancer-associated thrombosis? Br J Cancer. 2016;115:332-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Shao B, Wahrenbrock MG, Yao L, David T, Coughlin SR, Xia L, Varki A, McEver RP. Carcinoma mucins trigger reciprocal activation of platelets and neutrophils in a murine model of Trousseau syndrome. Blood. 2011;118:4015-4023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gebremeskel S, LeVatte T, Liwski RS, Johnston B, Bezuhly M. The reversible P2Y12 inhibitor ticagrelor inhibits metastasis and improves survival in mouse models of cancer. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:234-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mezouar S, Frère C, Darbousset R, Mege D, Crescence L, Dignat-George F, Panicot-Dubois L, Dubois C. Role of platelets in cancer and cancer-associated thrombosis: Experimental and clinical evidences. Thromb Res. 2016;139:65-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/