Published online Oct 15, 2025. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v17.i10.109450

Revised: June 21, 2025

Accepted: August 25, 2025

Published online: October 15, 2025

Processing time: 156 Days and 1.8 Hours

Childhood intestinal lymphoma is characterized by its insidious onset and the absence of specific clinical symptoms. The thinner abdominal wall in children significantly aids in the ultrasound visualization of the abdominal cavity and intestines. Although many typical cases of intestinal lymphoma can be diagnosed through ultrasound, physicians often either overlook these values or assume that ultrasound has limited diagnostic value for intestinal lymphoma.

To clarify the diagnosis of intestinal lymphoma and classify its severity using ultrasound, as well as to correlate this with prognosis.

The correlation between ultrasound diagnostic outcomes, laboratory indicators, and clinical prognosis was analyzed to demonstrate the effectiveness of ultrasound in assessing the severity of intestinal lymphoma and to provide new evidence for the diagnosis and treatment of the disease in children. A retro

Ultrasound was utilized to categorize 28 cases of intestinal lymphoma into focal segmental (15 cases) and extensive (13 cases) types. Ultrasound classification and LDH levels were significantly correlated with prognosis (P < 0.05), while pathological type, age, gender, and treatment modality showed no significant correlation (P > 0.05). Among ultrasound manifestations, there was a significant difference in LDH levels between the segmental and extensive groups (P < 0.05). The prognosis for children with extensive intestinal lymphoma was poorer than that for children with localized segmental intestinal lymphoma (P < 0.05).

Ultrasound can be used in the diagnosis and classification of intestinal lymphoma in children. Extensive intestinal lymphoma is associated with significantly elevated LDH and poor prognosis.

Core Tip: In the present retrospective study, our objective was to ascertain the relationship between ultrasonic classification of intestinal lymphoma, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels, pathological classification, and patient prognosis. The findings revealed a significant correlation between ultrasonic classification and LDH levels with patient prognosis. The prognosis for pediatric patients diagnosed with extensive intestinal lymphoma was observed to be less favorable compared to those with localized segmental intestinal lymphoma. From these outcomes, it can be inferred that ultrasonography serves as a valuable tool for the diagnosis and classification of intestinal lymphoma in pediatric patients. Furthermore, the presence of extensive intestinal lymphoma is correlated with markedly elevated LDH which are in of a favorable prognosis.

- Citation: Huang SF, Yang F, Chen WJ, Zhang XH. Ultrasound features of primary intestinal lymphoma in children and their correlation with prognosis: A two-center experiment. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2025; 17(10): 109450

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v17/i10/109450.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v17.i10.109450

Lymphoma refers to a group of malignant tumors that originate in lymph nodes or lymphatic tissues[1]. Intestinal lymphoma is characterized by its insidious onset and lack of specific clinical symptoms. Ultrasound examination is often performed initially due to digestive tract symptoms, such as abdominal pain and vomiting. The thin abdominal walls of children can provide good ultrasound conditions to visualize intestinal and abdominal lesions, especially in the discovery of intestinal lymphoma[2]. However, it is ignored by most clinical and ultrasound doctors or considered to have limited effectiveness in the diagnosis of abdominal lymphoma.

This study aimed to analyze the ultrasonic imaging characteristics, pathological features, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels, and prognosis of 28 cases of pediatric intestinal lymphoma. It summarizes the various sonographic manifestations of pediatric intestinal lymphoma and attempts to explore the underlying reasons for the different sonographic changes in the same disease. The study also explored the correlation between ultrasound diagnostic results, pathological classification, laboratory indicators, and clinical prognosis, further elucidating the effectiveness of ultrasound in assessing the severity of intestinal lymphoma lesions, providing new insights for the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric intestinal lymphoma.

We included children who underwent ultrasound examination between June 2015 and November 2024, who were clinically diagnosed with primary intestinal lymphoma and could be followed up. We excluded patients who were lost to follow-up or who had incomplete data.

A total of 36 pediatric cases were diagnosed with intestinal lymphoma by ultrasound, with complete data available for 28 cases and eight were lost to follow-up. There were 18 cases from Fujian Children’s Hospital and 10 from Hunan Children’s Hospital. The primary clinical symptoms included abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, and the presence of an abdominal mass.

Siemens Healthineers LOGIQ E9 and EPIQ7 color ultrasound diagnostic apparatus was used, equipped with convex array and linear array probe frequencies of 3.5-5.0 MHz and 7-14 MHz, respectively.

Sequential scanning was conducted from top to bottom along the digestive tract, alternating between longitudinal and transverse sections. Reverse scanning was performed moving from the rectum to the esophagus (from bottom to top). Combined forward-reverse scanning was carried out from the esophagus to the jejunum and ileum, and from the rectum to the ileocecal region. Step-by-step pressurization: To minimize the interference from intestinal gas during abdominal scans, the probe was slowly moved sideways to apply pressure to the area beneath it. All children underwent ultrasound examinations of the intestines, hepatobiliary system, pancreas, spleen, kidneys, ureters, and bladder.

Based on the characteristics of the ultrasound images of the primary site of intestinal lymphoma, the patients were classified into focal segmental and extensive types based on morphological features and the extent of involvement. All case image analyses were conducted by two ultasonographers with > 5 years of experience. The two doctors conducted a blind evaluation of the images, and if they had differing opinions, the more experienced chief physician would make the final decision on the classification.

The initial (pretreatment) LDH levels, surgical outcomes, and pathological results of the children were documented.

The prognosis for children was followed up and recorded as nonhealing (including fatal cases, cases with uncontrolled or relapsed primary disease), complete remission (cases without relapse for ≥ 3 years after treatment completion). The follow-up period for the surviving cases ranged from 1 to 8 years.

The study received approval from the Medical Ethics Committee of Fujian Children’s Hospital was exempted from obtaining informed consent from parents. All methods were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 22.0 software. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate the correlation between LDH level, ultrasonic classification, pathological classification, complications, treatment methods, age, sex, and prognosis of intestinal lymphoma. A t-test was used to assess the differences in mean LDH values between the segmental and extensive types. Cross-tabulation was used to compare the correlation between ultrasound typing with pathological typing and prognosis of intestinal lymphoma. A χ2 test was performed to analyze the correlation among ultrasound typing, pathological typing, and prognosis. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Twenty-eight cases of pediatric intestinal lymphoma confirmed by ultrasonic diagnosis and pathology, consisting of 24 males and four females with an average age of 7.36 years (range: 2.33-15 years), were studied at Fujian Children’s Hospital and Hunan Children’s Hospital between June 2015 and November 2024 (Table 1).

| Somatotype | Focal segmental type (n = 15) | Extensive type (n = 13) |

| Sex | ||

| Boy | 12 (80) | 12 (92.3) |

| Girl | 3 (20) | 1 (7.7) |

| Age (year) | 8.23 | 7.38 |

| Case classification | ||

| Burkitt lymphoma | 8 (53.3) | 10 (76.9) |

| Other types of B-cell lymphoma | 4 (26.7) | 3 (23.1) |

| Other types of lymphoma | 3 (20) | 0 (0) |

| LDH | ||

| Increase | 6 (40) | 13 (100) |

| Normal | 9 (60) | 0 (0) |

| Median (IU/L) | 300 | 935 |

| Complication | ||

| Intussusception | 8 (53.3) | 2 (15.4) |

| Peritoneal dropsy | 12 (92.3) | 13 (100) |

| Therapeutic method | ||

| Surgery | 5 (33.3) | 0 (0) |

| Surgery + chemotherapy | 4 (26.7) | 2 (15.4) |

| Chemotherapy | 6 (40) | 11 (84.6) |

| Prognosis | ||

| Cured | 12 (80) | 4 (30.8) |

| Not cured/death | 3 (20) | 9 (69.2) |

Out of the 28 cases of intestinal lymphoma, 23 involved the ileocecal region and/or ileum, two the rectum, one the duodenum, and two the colon. Based on the findings from intestinal ultrasound and the extent of involvement, the children with lymphoma were categorized into focal segmental and extensive types (Table 1). The focal segmental type accounted for 15 cases (54%), manifesting as lesions confined to a specific segment of the intestine, among which eight cases were complicated by intussusception. The extensive type accounted for 13 cases (46%), characterized by lesions involving extensive areas of the intestine, abdominal cavity, and lymph nodes, with metastasis to one or more organs (9 cases had liver metastasis, 3 cases kidney metastasis, and 2 cases pancreatic metastasis).

Focal segmental type: Categorized into clumped and thickening types based on morphological characteristics on ultrasound. The thickening type included the annular thickening type and the tumor-like thickening type.

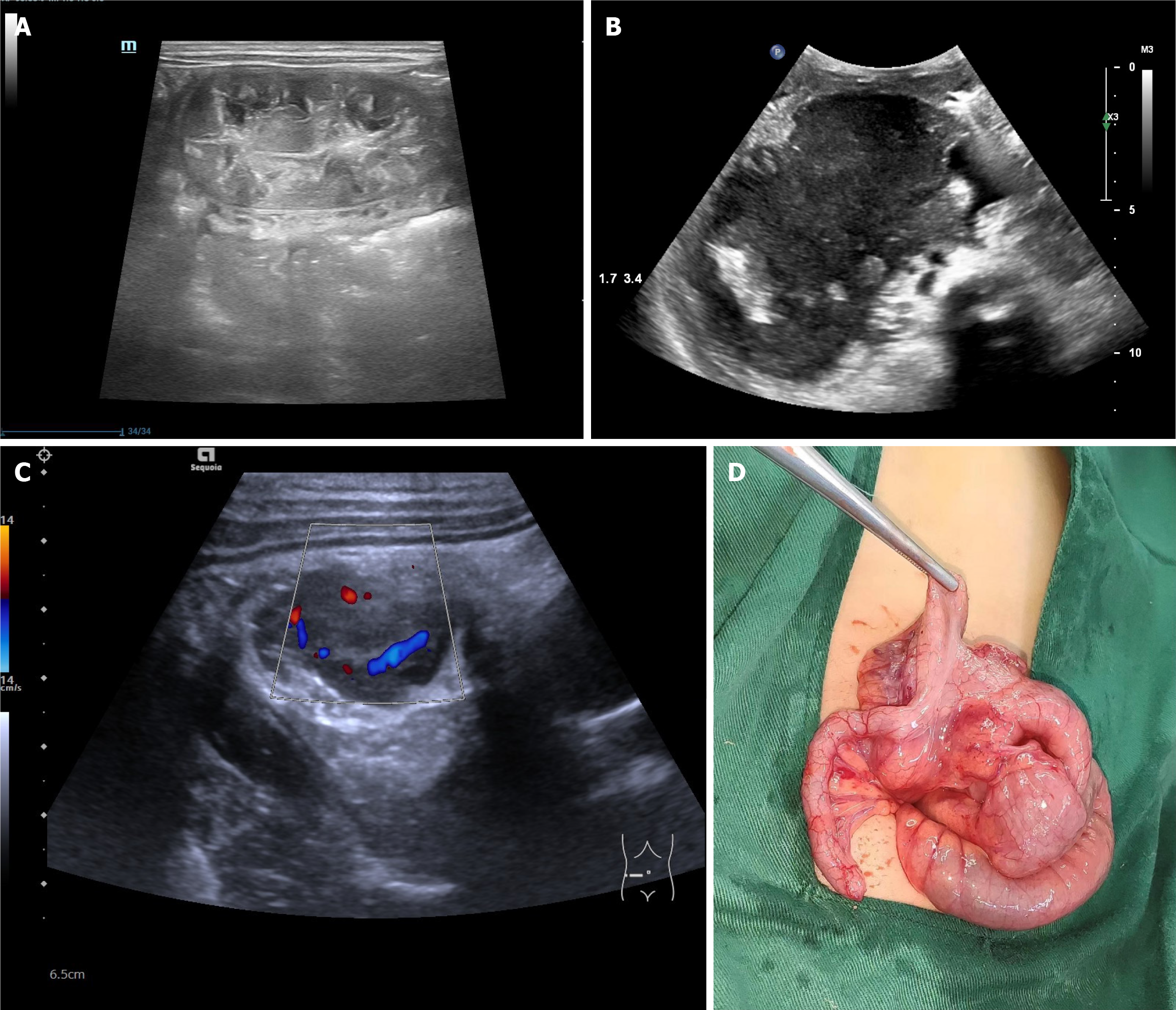

Clumping type: Seven cases exhibited irregular nodules or masses within the intestinal cavity or on the intestinal wall, with a broad base (Figure 1). Six of these were complicated by intussusception (85.7%), and eight were accompanied by ascites.

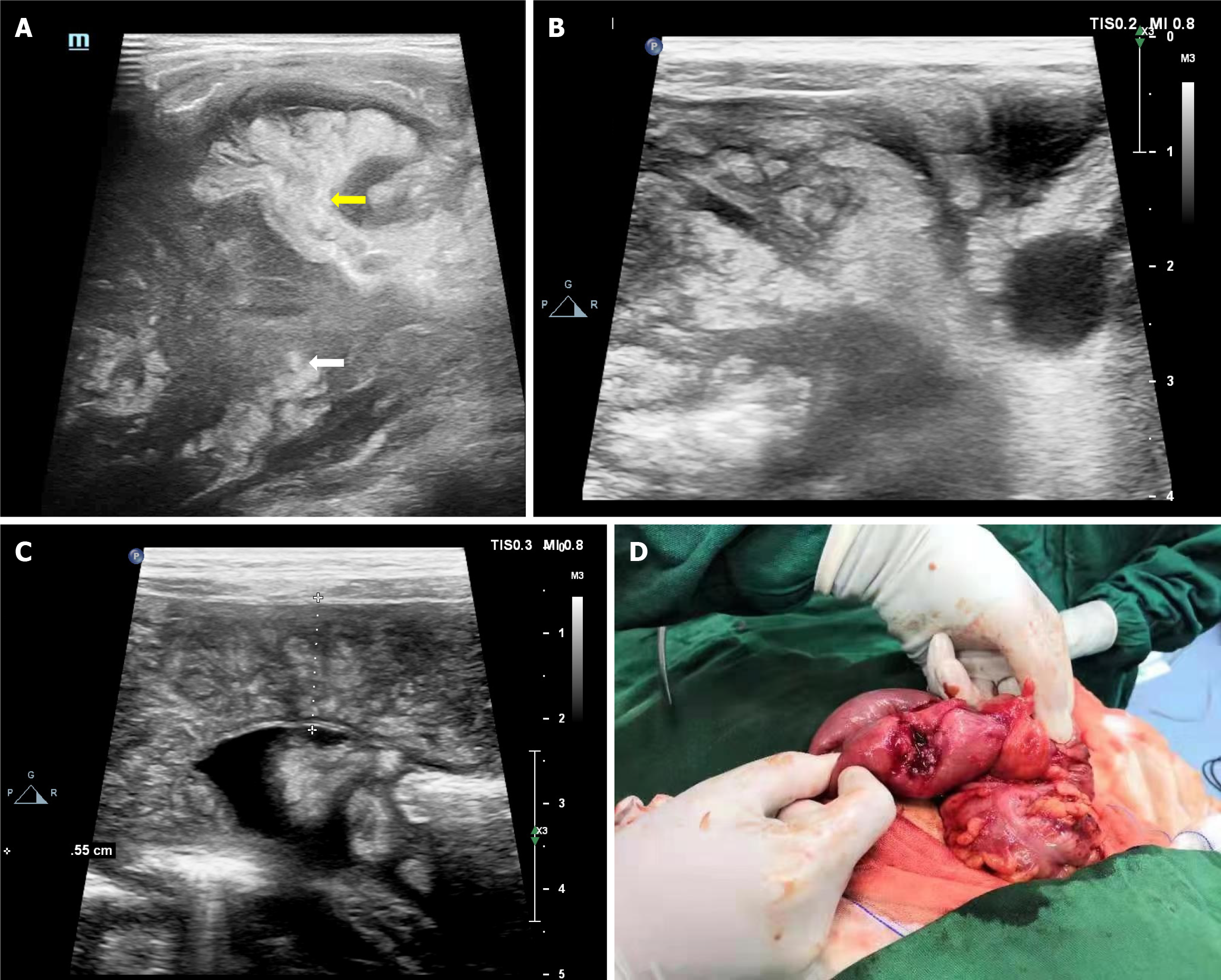

Thickening type: Eight cases displayed segmental thickening of the intestinal wall, with a longitudinal distribution along the intestinal wall. A longitudinal section revealed annular thickening or tumor-like appearances in two and six cases, respectively (Figure 1). The cross-section resembled a “pie”, composed of a significantly thickened intestinal wall and a relatively narrow intestinal cavity with a central mucosa (Figure 2). Additionally, the surrounding fat, omentum, and mesentery showed nodular or mass thickening in five of six cases (Figure 2). Color doppler imaging indicated the presence of nodules or masses, thickened intestinal walls, and abundant blood flow signals. Two cases were complicated by intussusception, and four cases presented with ascites.

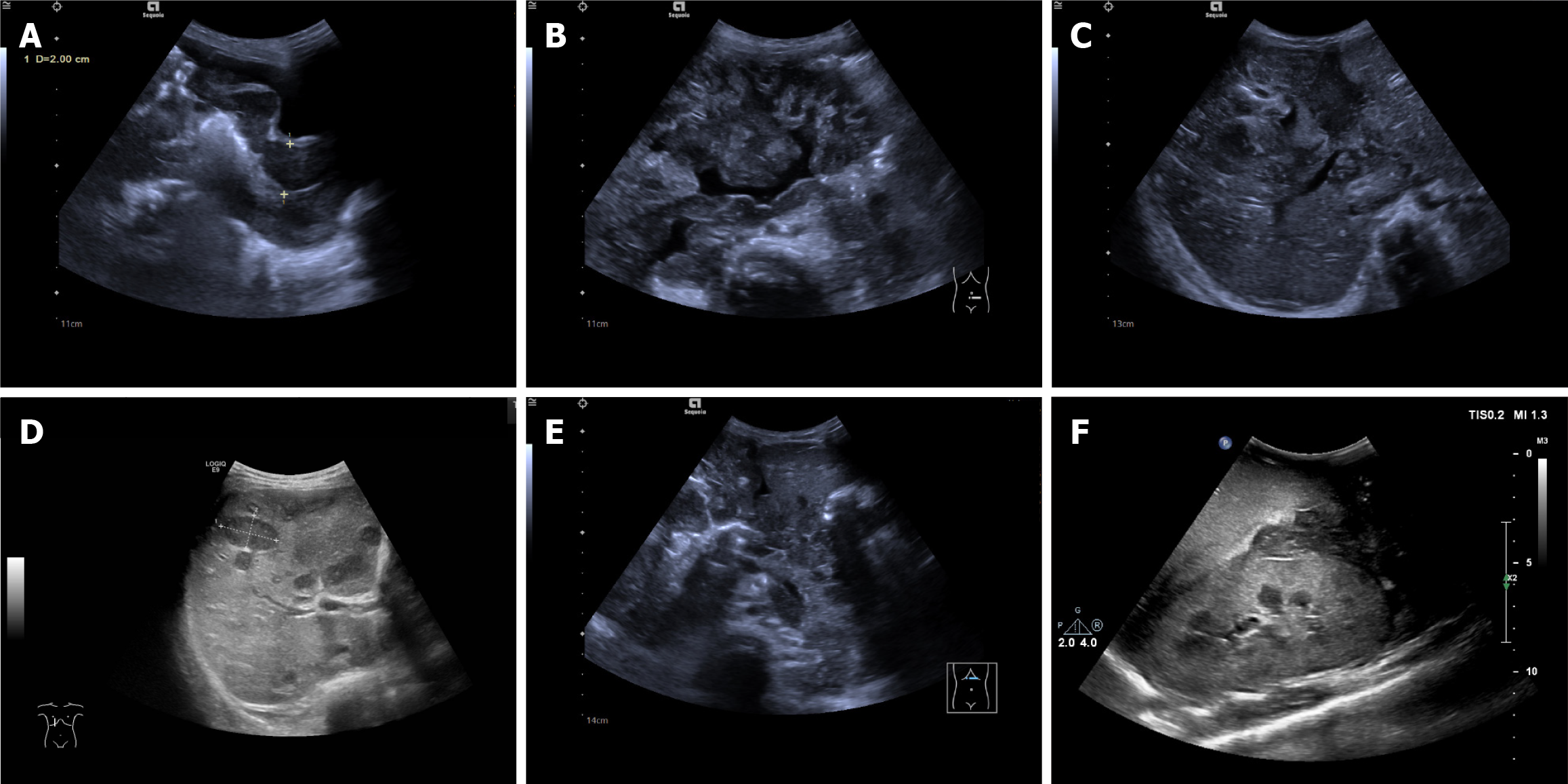

Extensive type: The intestinal wall exhibited tumor-like thickening in nine of 13 cases (69%), as well as annular thickening in four cases (31%); Both presenting with low echoes. The adjacent fat, omentum, and mesentery showed nodular or mass-like thickening in all 13 cases. The tumor tissue diffusely infiltrated and grew along the intestinal wall, spreading from the focal intestinal tract to most or all of the intestinal tract (Figure 3). The affected intestinal tract showed thickening, though not as pronounced as the primary lesion. Color doppler revealed abnormally rich blood flow signals in the thickened intestinal wall and mass-like echoes, with a reticular distribution similar to angioma-like blood flow. Lymphoma was widely disseminated in the abdominal cavity, and the thickened intestinal wall, mesentery, peritoneum, and expanded space contributed to a chaotic change in the abdominal acoustic image (all 13 cases) (Figure 3).

This group of cases included a wide variety of metastasis, involving a single or multiple organs. Among the nine cases with liver metastasis, six exhibited extensive thickening of the Glisson sheath in the liver, dendritic distribution of patchy hypoechoic areas, and absence of bile duct dilatation. Three cases revealed nodules or masses protruding into the parenchyma, which had clear boundaries and were rounded, mostly hypoechoic, and exhibited a “bull’s eye sign” (Figure 3). Normal liver parenchyma echoes were observed between the masses. Ultrasound examinations of three cases with kidney metastasis (all with liver metastasis) showed the following: Two cases of diffuse enlargement of both kidneys, clear cortical and medullary structures, cortical thickening, enhanced echoes, and the absence of space-occupying lesions (Figure 3); One case of multiple nodules in both kidneys displaying multiple patchy hypoechoic areas in the renal parenchyma, with unclear boundaries, no capsule, and a lack of definition in the kidney’s outline. Two cases had scattered patchy hypoechoic areas observed in the pancreas (Figure 3). Complications included ascites in 13 cases and intussusception in two.

In this study, 19 children (67.8%) exhibited elevated LDH levels, while nine (32.2%) had normal levels (normal values in Hunan Children’s Hospital: 0-450 U/L, 120-325 U/L in Fujian Children’s Hospital). All 13 cases of extensive intestinal lymphoma had elevated LDH levels (maximum 3527.5 U/L, minimum 935 U/L), and among the 15 cases of localized segmental intestinal lymphoma, six (40%) had increased LDH levels (maximum 1760 U/L, minimum 300 U/L). Extensive intestinal lymphoma showed a significantly higher incidence of elevated LDH compared to localized segmental intestinal lymphoma (P < 0.05).

Based on comprehensive data, including that obtained from magnetic resonance imaging, surgery, bone marrow cytology, body cavity fluid cytology, and biopsy, all 28 cases were diagnosed with intestinal lymphoma, which was consistent with the ultrasound findings. Additionally, the location of the intestinal lesions and the affected organs were consistent with those detected via ultrasound.

Eleven patients underwent surgery; among them, nine with relatively localized lesions had the affected intestinal segment resected, the two cases with more extensive involvement only had tumor biopsies taken. Five of the 11 children with the focal mass type underwent surgical resection of the affected bowel without receiving chemotherapy, whereas six underwent resection followed by chemotherapy. Another 17 cases proceeded directly to chemotherapy after diagnosis via bone marrow cytology, body cavity fluid cytology combined with imaging.

A total of 25 cases (89.3%) were diagnosed with B-cell lymphoma, including 18 cases (72%) with Burkitt’s lymphoma; seven (28%) other types of B-cell lymphoma (including 4 high-grade B-cell lymphoma, 2 diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and 1 aggressive B-cell lymphoma); three cases (10.7%) with other categories of lymphomas (including 2 T-cell lymphoma and 1 precursor/T-lymphoblastic lymphoma).

Three patients died. Nine were not cured or relapsed. Sixteen achieved complete remission, with no recurrence during 3 years of follow-up (Table 1). In the patients with focal segmental type, three were nonhealing and 12 were cured. In the patients with extensive type, there were three deaths, four that were not recoverable, two with relapse, and four were cured.

Binary logistic regression analysis showed that ultrasound classification and LDH levels were significantly correlated with prognosis (P < 0.05), while pathological type, age, gender, and treatment modality showed no significant correlation (P > 0.05). Among ultrasound manifestations, there was a significant difference in LDH levels between the segmental and extensive groups (P < 0.05). The prognosis for children with extensive intestinal lymphoma was poorer than that for children with localized segmental intestinal lymphoma (P < 0.05); however, there was no significant difference in pathological types between the two groups (P > 0.05) (Table 2).

| Somatotype | Prognosis | P value | |

| Cured (n = 16) | Not cured/death (n = 12) | ||

| Ultrasonic typing | 0.009 | ||

| Focal segmental type | 12 (75) | 3 (25) | |

| Extensive type | 4 (25) | 9 (75) | |

| Sex | 0.436 | ||

| Boy | 13 (81.25) | 11 (91.7) | |

| Girl | 3 (18.75) | 1 (8.3) | |

| Age (year) | 7.65 | 7.38 | 0.634 |

| Case classification | 0.378 | ||

| Burkitt lymphoma | 10 (62.5) | 8(66.7) | |

| Other types of B-cell lymphoma | 3 (18.78) | 4(33.3) | |

| Other types of lymphoma | 3 (18.75) | 0 (0) | |

| LDH | 0.002 | ||

| Increase | 7 (43.75) | 12 (100) | |

| Normal | 9 (56.25) | 0 (0) | |

| Median (IU/L) | 301 | 1127 | |

| Complications | 0.397 | ||

| Intussusception | 3 (18.75) | 0 (0) | |

| Peritoneal dropsy | 9 (56.25) | 9 (75) | |

| Intussusception + peritoneal dropsy | 4 (25) | 3 (25) | |

| Therapy method | 0.160 | ||

| Surgery | 4 (25) | 1 (8.3) | |

| Surgery + chemotherapy | 4 (25) | 2 (16.7) | |

| Chemotherapy | 8 (50) | 9 (75) | |

Lymphoma constitutes 10%-15% of all childhood malignant tumors and is the third most common type overall[1]. Research indicates that the average age of lymphoma onset is 8 years, and males account for 10%-15% of these cases. The median age of onset in the current group of children was 7 years, with a male-to-female ratio of 24:4, which is slightly lower than figures reported in literature[1]. Childhood abdominal lymphoma presents with a subtle onset and lacks specific clinical symptoms. Children frequently seek medical attention due to digestive tract symptoms, such as abdominal pain and vomiting, while ultrasound is the preferred imaging method. Early detection, diagnosis, and treatment can significantly improve the 3-5-year survival rate of children[2] and may even result in a complete cure. Ultrasound examination is effective for the accurate diagnosis of intestinal lymphoma, based on the markedly low echo of the intestinal wall and the high echo of the surrounding fat nodules. It can also determine the location and extent of lesions. According to the pathological characteristics of intestinal lymphoma, lesions originate from the intestinal mucosal lamina propria and submucosa. The lymphoid tissue gradually infiltrates the interior or exterior of the intestinal cavity and can manifest as localized or diffuse intestinal wall thickening at various stages of the disease. The intestinal wall shows irregular thickening, leading to the loss of the four-layer structure and formation of a space-occupying lesion within the intestinal wall. The tumor may invade the serosal layer, mesenteric omentum, and lymph nodes, forming an external mass. It may also be accompanied by the enlargement of peripheral lymph nodes and the metastasis of distant lymph nodes and organs[3].

In this study, ultrasound was used to classify lesions into various groups based on the extent of intestinal invasion (limited to a section of the intestine or with the involvement of other abdominal organs).

Ultrasound classification categorizes intestinal lymphoma into focal segmental and extensive types. Focal segmental lesions affect a portion of the intestine, are confined to the primary intestinal site, do not cross segments to affect other parts of the intestine, and do not involve abdominal organs. Distant metastasis is not observed. In this category of cases, the ileocecal region is the most common site[4]. This section of the intestinal mesentery or the lymph nodes in this area may be affected. Ultrasound manifestations include the following: The intestinal tract in the affected area is thickened in an annular shape and exhibits a low echo. This condition may be associated with the following pathological mechanisms: (1) Lymphoma cells diffuse through the wall, involving the submucosa and nearly destroying these layers; and (2) Secondary lymphatic dilatation and obstruction of reflux cause intestinal wall edema[5]. It may also present as a low-echo mass on the intestinal wall. This type is most likely to be complicated by intussusception (6/7 cases; 85.7% combined with intussusception), and intestinal lymphoma is often diagnosed based on the discovery of intussusception[6].

The extensive type is characterized by evident thickening of the intestinal wall in the primary lesion area, which often presents a tumor-like thickening, and the tumor tissue diffusely infiltrates and grows along the intestinal wall. The disease spreads from the primary intestinal area to most or even all of the intestines. The disseminated intestines attained less degree of, along with the mesentery, peritoneum, and abdominal organs (100%). The liver (9/13 cases, 69.2%) was the most commonly involved organ. All nine cases showed sheet-like or small nodular hypoechoic areas distributed along the hepatic sheath. This phenomenon is related to the activation and proliferation of the lymphatic system. Tumor tissue metastasizes through the lymphatic vessels and invades the lymphatic tissue in the portal area of the liver, which results in Gleason sheath distribution lymphoid tissue hyperplasia[7]. All three cases of renal involvement were accompanied with liver involvement and showed diffuse hypoechoic or low masses in the kidney to the invasion of intrarenal lymphoid tissue.

Retroactive image analysis revealed that the lymphoma lesion area exhibited intestinal tumor-like thickening and a low echo (15/15), with the intestinal wall being circular or showing eccentric thickening. Nodular or mass-like thickening of the surrounding fat or omentum and mesentery (14/15, 93.3%) is characteristic of intestinal lymphoma and can serve as a crucial diagnostic criterion for intestinal lymphoma. In the extensive lymphoma group, the lesions were widely spread throughout the abdominal cavity. Thickened intestinal wall, mesentery, peritoneum, and widened spaces induced a chaotic abdominal sonographic appearance, which is a common diagnostic feature of intestinal lymphoma and an important basis for the assessment of the entire abdominal cavity.

Based on ultrasonic morphology and disease severity, the cases in this group were divided into focal segmental and extensive types. Children with early focal segmental type combined with intussusception underwent surgical resection of the local bowel, but developed the extensive type without chemotherapy. We propose that focal segmental and extensive types represent different developmental stages of the same disease. Extensive intestinal lymphoma is the manifestation of the progression of the focal segmental type. In B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (B-NHL), chemotherapy is indicated even in patients with R0 resection, yet with lower intensity[8]. It is important to be aware that complete resection can lead to downstaging only from stage II to stage I B-NHL.

Generalized extensive intestinal lymphoma cells involve the primary site and most of the intestines, as well as the entire abdominal cavity, and most are combined with abdominal organs. Some research has indicated that lymphoma combined with organ metastasis, especially renal metastasis, often signifies a late stage of the disease and is associated with poor prognosis indicators[9]. Among the 13 cases of the extensive type in this study, three died and four did not recover. All cases that were relieved or cured required long-term chemotherapy. Correlation analysis revealed a significant difference in prognosis between the two groups, suggesting that the extensive type had a poorer prognosis.

The current view is that a significant increase in LDH indicates a poor prognosis of lymphoma or a more serious condition[10]. This group of cases revealed a significantly higher incidence of elevated LDH in extensive intestinal lymphoma than in focal segmental intestinal lymphoma (100% vs 40%), which also reflects that the extensive type has a poorer prognosis and is more serious than the focal segmental type.

Childhood lymphoma is mainly NHL, with Burkitt lymphoma being the most common and ranking first in the pathological classification of childhood gastrointestinal lymphoma[8]. All cases in the studied group were NHL, with Burkitt lymphoma being the most common (18/28, 64%), consistent with the literature. Studies have shown that in the Western population, 60%-80% of intestinal lymphomas are B-cell lymphomas, mainly diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the distal small intestine[9]. In this group of cases, B-cell lymphoma accounted for 89%, which is consistent with research reports. There was no significant correlation between the ultrasound classification of intestinal lymphoma and pathological classification.

In this group of children with intestinal lymphoma, most presented with nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms, and imaging often indicated intussusception or abdominal masses. These findings underscore the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for intestinal lymphoma in the differential diagnosis of acute pediatric abdominal conditions.

Does the ultrasonic classification influence treatment decisions? Despite systemic chemotherapy being the standard of care for B-NHL, previous studies have documented that up to half of pediatric patients with abdominal presentations undergo emergency laparotomy due to acute events such as bowel obstruction or intussusception[11]. For example, in the focal segmental type group in this study, 9 patients underwent surgical treatment due to indications of intussusception (8/15) or (1/15) intestinal wall masses. All children who received postoperative chemotherapy were cured, which is consistent with the conclusions reported in the literature. Intraoperative identification and complete resection of lymphomatous masses, where possible, are recommended, as surgical excision may lead to disease downstaging and lower-intensity chemotherapy protocols[11].

The literature emphasizes that extensive or mutilating surgery should be avoided, even in cases with advanced local tumor burden, due to the overall favorable prognosis and the potential for surgical complications to delay chemotherapy the primary therapeutic modality[12]. This study demonstrates that ultrasound is effective in diagnosing extensive-type intestinal lymphoma. Whether manifested as tumor-like hyperplasia confined to the intestinal wall or as diffuse involvement of the abdominal cavity and metastatic sites, ultrasonographic findings in such cases are notably specific. Consequently, in patients with diffuse disease and no urgent surgical indications (e.g., obstruction, intussusception, or perforation), ultrasound offers clinicians rapid, noninvasive diagnostic clarity, facilitating early initiation of chemotherapy. Early ultrasonographic diagnosis helps avoid unnecessary surgical delays and minimizes the physiological stress of invasive interventions in already vulnerable pediatric patients.

This study had some limitations. The sample size was small, and the grouping comparisons were somewhat crude; therefore, some results may be subject to bias. Additionally, follow-up data for some cases were obtained through parental reports, which may have introduced further bias. However, we aim to address these limitations through ongoing research with a larger number of cases in the future.

Ultrasound is utilized for the precise diagnosis and classification of intestinal lymphoma in children. The LDH value significantly increased, indicating poor prognosis. Ultrasonography had high diagnostic value in diagnosing intestinal lymphoma in children, and the prognosis should be predicted through typing.

| 1. | Siegel DA, King J, Tai E, Buchanan N, Ajani UA, Li J. Cancer incidence rates and trends among children and adolescents in the United States, 2001-2009. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e945-e955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Burkhardt B, Oschlies I, Klapper W, Zimmermann M, Woessmann W, Meinhardt A, Landmann E, Attarbaschi A, Niggli F, Schrappe M, Reiter A. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in adolescents: experiences in 378 adolescent NHL patients treated according to pediatric NHL-BFM protocols. Leukemia. 2011;25:153-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wang XY, Zhu YT, Zheng S, Xiao F, Zhu YY, Che S, Hu P. Ultrasound manifestations of primary intestinal non-Hodgkin lymphoma with liver metastasis in a child. J Clin Ultrasound. 2024;52:1176-1178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kim SJ, Choi CW, Mun YC, Oh SY, Kang HJ, Lee SI, Won JH, Kim MK, Kwon JH, Kim JS, Kwak JY, Kwon JM, Hwang IG, Kim HJ, Lee JH, Oh S, Park KW, Suh C, Kim WS. Multicenter retrospective analysis of 581 patients with primary intestinal non-hodgkin lymphoma from the Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma (CISL). BMC Cancer. 2011;11:321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Asai S, Miyachi H, Hara M, Fukagawa S, Shimamura K, Ando Y. Extensive wall thickening in intestinal Burkitt lymphoma. J Ultrasound Med. 2002;21:657-661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zhang R, Zhang M, Deng R, Li Y, Guo C. Lymphoma-related intussusception in children: diagnostic challenges and clinical characteristics. Eur J Pediatr. 2024;183:219-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Morsi A, Abd El-Ghani Ael-G, El-Shafiey M, Fawzy M, Ismail H, Monir M. Clinico-pathological features and outcome of management of pediatric gastrointestinal lymphoma. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2005;17:251-259. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Mason EF, Kovach AE. Update on Pediatric and Young Adult Mature Lymphomas. Clin Lab Med. 2021;41:359-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Buyukpamukçu M, Varan A, Aydin B, Kale G, Akata D, Yalçin B, Akyuz C, Kutluk T. Renal involvement of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and its prognostic effect in childhood. Nephron Clin Pract. 2005;100:c86-c91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wu S, Du J, Ma J, Huang L, Peng Z, Ling Y, Deng X, Zhu W, Li H, Wang H, Li Y. A Survival Prognostic Model for Gastro-Intestinal Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Blood. 2024;144:3087-3087. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Bussell HR, Kroiss S, Tharakan SJ, Meuli M, Moehrlen U. Intussusception in children: lessons learned from intestinal lymphoma as a rare lead-point. Pediatr Surg Int. 2019;35:879-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Reiter A, Schrappe M, Tiemann M, Ludwig WD, Yakisan E, Zimmermann M, Mann G, Chott A, Ebell W, Klingebiel T, Graf N, Kremens B, Müller-Weihrich S, Plüss HJ, Zintl F, Henze G, Riehm H. Improved treatment results in childhood B-cell neoplasms with tailored intensification of therapy: A report of the Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster Group Trial NHL-BFM 90. Blood. 1999;94:3294-3306. [PubMed] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/