Published online Oct 15, 2025. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v17.i10.108539

Revised: May 26, 2025

Accepted: September 1, 2025

Published online: October 15, 2025

Processing time: 180 Days and 22.7 Hours

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common cancers and CRC patients are among the most common intensive care unit (ICU) admitted cancer patients. However, their prognosis and evaluation methods are rarely studied.

To determine the short-term mortality outcome and identify the potential prognostic factors of CRC cancer patients admitted to the ICU.

A multicenter cross-sectional study was performed from May 10, 2021 to July 10, 2021 at the ICU departments of 37 cancer specialized hospitals in China, and included patients aged ≥ 14 years with ICU duration ≥ 24 hours. Clinical records of patients with a primary CRC diagnosis were reviewed. Patients were separated into groups according to 90-day survival. Characteristics between groups were compared. Univariate and multivariate regression tests were used to analyze the correlated factors of ICU outcomes. Predictive values of disease severity scores were assessed using receiver operating characteristic curve analysis.

In total, 189 CRC patients were included in the study. The 90-day mortality was 12.2%. Patients who died showed differences compared to patients who survived mostly in terms of disease severity and ICU complications. It appears that patients admitted to the ICU from a clinical ward due to emergencies may have a higher risk of mortality while surgical management was associated with better survival. In multivariate analysis, only che

ICU admitted CRC patients appear to have low short-term mortality which requires further confirmation in pro

Core Tip: This study advances the literature by providing robust data on the prognosis of intensive care unit-admitted colorectal cancer patients, clarifying the role of clinical management on survival outcomes, and highlighting the need for improved prognostic tools. These findings are actionable for clinicians managing colorectal cancer patients and foundational for future research aimed at optimizing care and reducing mortality in this population.

- Citation: Dong Q, Xia R, Xing XZ, Wang CS, Ma G, Wang HZ, Zhu B, Zhao JH, Zhou DM, Zhang L, Huang MG, Quan RX, Ye Y, Zhang GX, Jiang ZY, Huang B, Xu SL, Xiao Y, Zhang LL, Lin RY, Ma SL, Qiu YA, Zheng Z, Sun N, Xian LW, Li J, Zhang M, Guo ZJ, Tao Y, Zhou XZ, Chen W, Wang DX, Chi JY, Wang DH, Liu KZ. Intensive care unit outcomes and prognostic factors of colorectal cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2025; 17(10): 108539

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v17/i10/108539.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v17.i10.108539

Advances in cancer treatment have significantly improved survival rates among cancer patients in recent years. During disease progression and treatment, intensive care unit (ICU) management may be warranted due to complications or treatment-associated side effects[1,2]. Alongside improved survival outcomes, the number of cancer patients requiring ICU care has risen substantially[3,4]. Balancing potential medical outcomes, individual rights and desires, and economic burdens necessitates identifying patients most likely to benefit from ICU admission and establishing timely prognostic evaluations, both of which hold significant clinical importance[5,6]. Although various studies on the characteristics and outcomes of ICU-admitted cancer patients have been conducted[7-10], available data remain fragmented, and consensus on admission criteria is still lacking.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer worldwide and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths globally[11,12]. In China, CRC was the second most common cancer and the fourth most common cause of cancer death in 2020[13]. CRC patients may require ICU admission for postoperative complications, cancer-related emergencies (e.g., obstruction and perforation), treatment-related toxicities (e.g., sepsis and chemotherapy-induced organ dysfunction), systemic complications, or palliative care crises[14,15]. CRC is among the most common malignancies in ICU settings and represents the most frequent surgical admission to the ICU for cancer patients[16,17]. Compared to non-cancer ICU patients, CRC patients exhibit higher complication rates, longer hospital stays, poorer survival outcomes, and greater healthcare costs[18-20].

Understanding the characteristics and outcomes of CRC patients requiring ICU care is critical for optimizing management and improving prognoses. First, risk stratification is needed to identify high-risk populations and prioritize clinical monitoring[21,22]. Second, given the frequent constraints on ICU resources, effective risk assessment tools are essential to guide clinical decision-making and avoid unnecessary admissions[23,24]. Furthermore, accurate risk pre

Numerous studies have addressed risk assessment in CRC patients, but most focus on postoperative outcomes, as ICU transfer following surgery remains a common strategy despite clinical debate over its utility[26-28]. However, postope

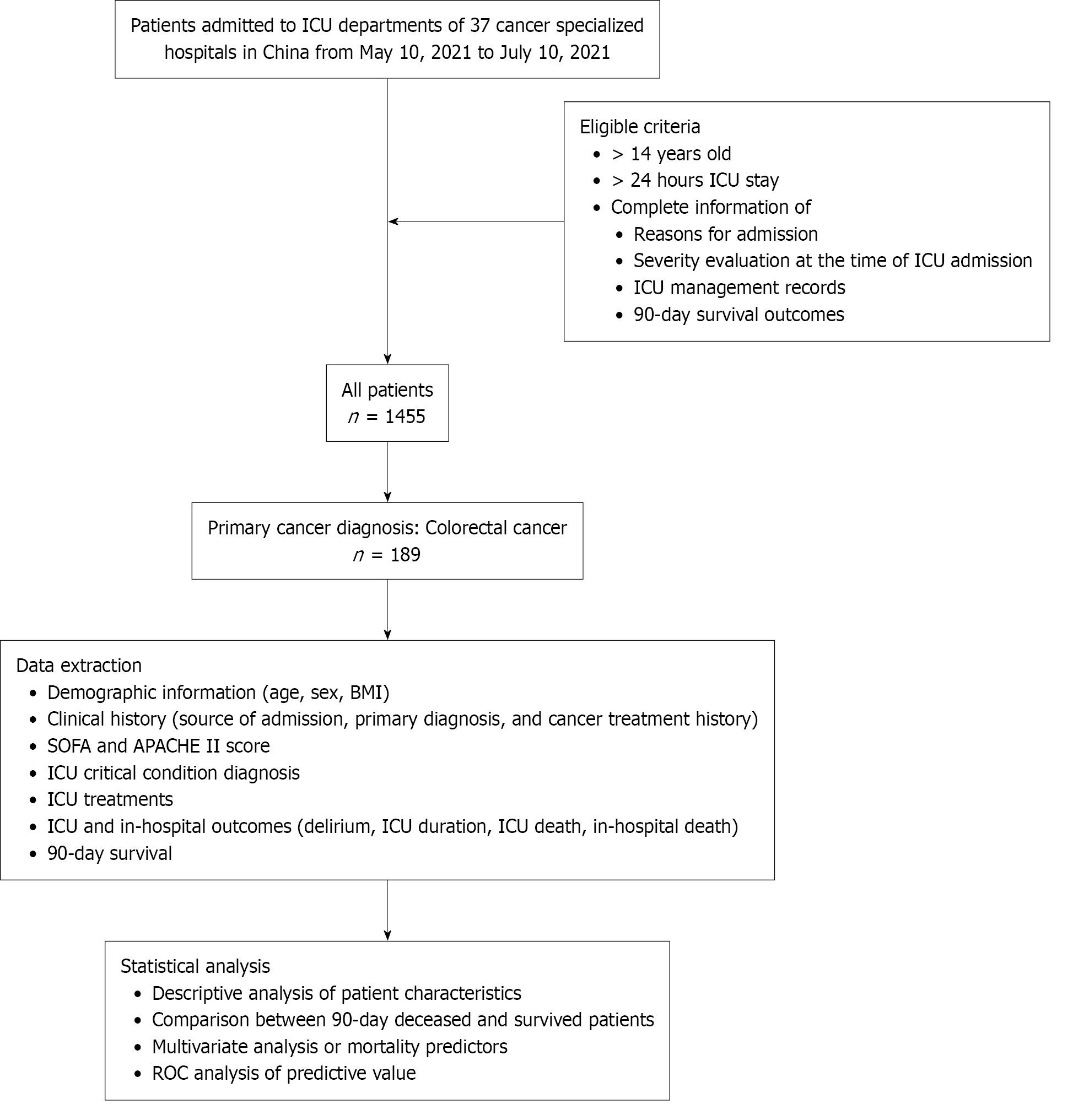

Patients admitted into ICU departments of 37 cancer specialized hospitals in China from May 10, 2021 to July 10, 2021 were screened for a cross-sectional study. The clinical records of all admitted patients in the ICUs of participating centers were screened and considered eligible if the following information was complete: Reasons for admission to the ICU and underlying medical history, severity evaluation at the time of ICU admission, incidence of sepsis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, acute kidney injury (AKI), treatment of intensive care medicine-related diagnosis and treatment regimen, in-hospital outcomes, and 90-day survival at follow-up. Patients aged < 14 years and those with an ICU stay < 24 hours were excluded. Patients were separated into two groups according to the 90-day mortality outcome. Differences between the groups in terms of characteristics at baseline and during ICU management were analyzed to explore the predictors of short-term mortality. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study was approved by the Ethic Committee of Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital (No. bc2021065). The requirement for written informed consent was waived due to the retrospective study design. The study process is depicted in Figure 1.

This study retrospectively gathered data from patient clinical records. The extracted information encompassed demo

Medical charts of individuals admitted to ICUs across participating centers were reviewed for eligibility, requiring comprehensive documentation of key parameters: Admission rationale and pre-existing comorbidities, illness severity scores at ICU entry, records on ICU complications such as occurrence of sepsis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, or AKI, therapeutic interventions aligned with critical care diagnoses, hospitalization outcomes, and 90-day post-discharge survival outcomes. Exclusion criteria comprised individuals under 14 years of age or those with an ICU duration shorter than 24 hours. The study was coordinated with data quality control. An electronic data collection Excel form was sent to participating centers. All data were extracted and filled in collection forms according to pre-set standards and then checked and confirmed by quality control officers. The final data of this study were then shared by all the participating units. This information has been added in the revised methods.

To assess the normality of continuous variables, the Shapiro-Wilk test was employed. As the data exhibited a non-normal distribution, continuous variables were summarized as median with interquartile range. Group comparisons of these variables were conducted using the Mann-Whitney U test. The categorical variables are presented as frequency counts and percentages (%). The Wilcoxon rank sum test was utilized for ordinal categorical data, and either the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was applied for nominal categorical comparisons. Factors associated with 90-day mortality were evaluated using both univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses. Variable selection for the multivariable model was performed via backward stepwise regression. The predictive performance of the SOFA and APACHE II scores was compared by generating time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves using the R package time ROC, and the area under the curve was computed for each. All analyses were performed using R version 4.3.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing), employing two-sided tests with a significance threshold of α = 0.05.

The study consisted of 189 patients admitted to the ICU with a primary diagnosis of CRC. As detailed in Table 1, the 90-day survival rate for this group was 87.8% (n = 166). No significant differences were found in baseline demographics (age, gender, and BMI) when compared between the surviving and deceased patients. Deceased patients had a higher percentage of targeted therapy and chemotherapy history. In the deceased group, more patients were transferred unplanned to the ICU from a clinical ward, and surviving patients were more likely to undergo elective or emergency surgery. Deceased patients had higher severity scores and were more likely to experience complications including sepsis, respiratory failure, AKI, and shock on admission to the ICU. In addition, deceased patients tended to receive more anti-infection treatment and a lower percentage received conventional oxygen therapy instead of mechanical ventilation. These results indicated that the overall survival of CRC patients admitted to the ICU was good with a low mortality rate. Patients who died showed differences to those who survived mostly in terms of disease severity and ICU complications. It appears that patients admitted to the ICU from clinical wards due to emergencies may have a higher risk of death while surgical management was associated with better survival.

| Variables | All (n = 189) | Survived at 90 days (n = 166) | 90-day mortality (n = 23) | P value |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 69.0 (60.0, 76.0) | 69.0 (61.2, 76.0) | 66.0 (57.5, 79.5) | 0.663 |

| Gender | 0.650 | |||

| Female | 58 (30.7) | 50 (30.1) | 8 (34.8) | |

| Male | 131 (69.3) | 116 (69.9) | 15 (65.2) | |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 22.5 (19.8, 25.1) | 22.9 (19.8, 25.2) | 22.0 (20.9, 22.7) | 0.460 |

| Treatment history | ||||

| Target therapy | 16 (8.5) | 9 (5.4) | 7 (30.4) | 0.001a |

| Immunotherapy | 5 (2.6) | 5 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| Chemotherapy | 33 (17.5) | 24 (14.5) | 9 (39.1) | 0.007a |

| Radiotherapy | 8 (4.2) | 6 (3.6) | 2 (8.7) | 0.252 |

| Transferring source | < 0.001a | |||

| Operation room | 119 (63.0) | 114 (68.7) | 5 (21.7) | |

| Emergency department | 7 (3.7) | 6 (3.6) | 1 (4.3) | |

| Clinical ward | 61 (32.3) | 46 (27.7) | 15 (65.2) | |

| Other hospitals | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (8.7) | |

| Planned transfer | 95 (50.3) | 77 (53.6) | 18 (21.7) | 0.004a |

| Elective or emergency surgery | < 0.001a | |||

| No surgery | 33 (17.5) | 19 (11.4) | 14 (60.9) | |

| Elective | 131 (69.3) | 124 (74.7) | 7 (30.4) | |

| Emergency | 25 (13.2) | 23 (13.9) | 2 (8.7) | |

| Severity scores | ||||

| SOFA, median (IQR) | 3.0 (2.0, 5.0) | 3.0 (1.0, 5.0) | 5.0 (3.0, 9.5) | 0.002a |

| APACHE II, median (IQR) | 11.0 (8.0, 15.0) | 10.0 (8.0, 14.0) | 18.0 (14.5, 21.5) | < 0.001a |

| ICU diagnosis | ||||

| Sepsis | 104 (55.0) | 85 (51.2) | 19 (82.6) | 0.005a |

| ARDS | 17 (9.0) | 14 (8.4) | 3 (13.0) | 0.441 |

| Respiratory failure | 48 (25.4) | 38 (22.9) | 10 (43.5) | 0.034a |

| AKI | < 0.001a | |||

| None | 171 (90.5) | 155 (93.4) | 16 (69.6) | |

| Grade I | 9 (4.8) | 5 (3.0) | 4 (17.4) | |

| Grade II | 3 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (13.0) | |

| Grade III | 6 (3.2) | 6 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Shock | 55 (29.1) | 44 (26.5) | 11 (47.8) | 0.035a |

| Anti-infection treatment | ||||

| Carbapenems | 60 (31.7) | 47 (28.3) | 13 (56.5) | 0.006a |

| β-lactam | 59 (31.2) | 50 (30.1) | 9 (39.1) | 0.382 |

| Glycopeptides | 28 (14.8) | 22 (13.3) | 6 (26.1) | 0.119 |

| Tigecycline | 10 (5.3) | 8 (4.8) | 2 (8.7) | 0.349 |

| Echinocandins | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (4.3) | 0.229 |

| Triazoles | 8 (4.2) | 5 (3.0) | 3 (13.0) | 0.059 |

| Other treatment | ||||

| Mechanical ventilation | 76 (40.2) | 65 (39.2) | 11 (47.8) | 0.427 |

| Conventional oxygen therapy | 174 (92.1) | 158 (95.2) | 16 (69.6) | 0.001a |

| Sedation treatment | 48 (25.4) | 39 (23.5) | 9 (39.1) | 0.106 |

Cox regression analysis, at both the univariate and multivariate setting, were performed to further explore potential outcome predictors. In univariate analysis, factors correlated with higher mortality risk included treatment history, transfer from a clinical ward, unplanned transfer, higher severity scores, ICU complication diagnosis (sepsis, respiratory failure, AKI, and shock) and certain anti-infection treatments (Table 2). Surgical management and conventional oxygen therapy in the ICU were associated with a lower risk of death. In multivariate analysis, only chemotherapy, elective surgery and conventional oxygen therapy were statistically identified as independent correlators of 90-day mortality.

| Variables, demographics | Univariate analysis1 | Multivariate analysis | ||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age (years) | 0.99 (0.96, 1.03) | 0.643 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | Reference | |||

| Male | 0.82 (0.35, 1.94) | 0.658 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.97 (0.86, 1.08) | 0.549 | ||

| Treatment history | ||||

| Target therapy | 5.43 (2.23, 13.22) | < 0.001 | ||

| Immunotherapy | - | - | ||

| Chemotherapy | 3.38 (1.46, 7.80) | 0.004 | 2.66 (1.04, 6.80) | 0.041a |

| Radiotherapy | 2.18 (0.51, 9.28) | 0.294 | ||

| Transferring source | ||||

| Operation room | Reference | |||

| Emergency department | 3.85 (0.45, 32.96) | 0.218 | ||

| Clinical ward | 6.65 (2.41, 18.30) | < 0.001 | ||

| Other hospitals | - | - | ||

| Unplanned transfer | 3.83 (1.42, 10.31) | 0.008 | ||

| Elective or emergency surgery | ||||

| No surgery | Reference | |||

| Elective | 0.10 (0.04, 0.25) | < 0.001 | 0.20 (0.07, 0.58) | 0.003a |

| Emergency | 0.15 (0.04, 0.68) | 0.013 | 0.26 (0.06, 1.24) | 0.091 |

| Severity scores | ||||

| SOFA | 1.19 (1.10, 1.30) | < 0.001 | ||

| APACHE II | 1.12 (1.07, 1.17) | < 0.001 | 1.06 (1.00, 1.12) | 0.071 |

| ICU diagnosis | ||||

| Sepsis | 4.16 (1.42, 12.24) | 0.010 | ||

| ARDS | 1.59 (0.47, 5.37) | 0.451 | ||

| Respiratory failure | 2.46 (1.08, 5.62) | 0.032 | ||

| AKI | 5.16 (2.12, 12.56) | < 0.001 | ||

| Shock | 2.41 (1.06, 5.46) | 0.035 | ||

| Anti-infection treatment | ||||

| Carbapenems | 3.10 (1.36, 7.07) | 0.007 | ||

| β-lactam | 1.42 (0.61, 3.28) | 0.411 | ||

| Glycopeptides | 2.19 (0.86, 5.56) | 0.098 | ||

| Tigecycline | 1.84 (0.43, 7.85) | 0.410 | ||

| Echinocandins | 4.19 (0.56, 31.13) | 0.161 | 0.15 (0.01, 1.43) | 0.099 |

| Triazoles | 3.95 (1.17, 13.31) | 0.027 | ||

| Other treatment | ||||

| Mechanical ventilation | 1.41 (0.62, 3.20) | 0.410 | ||

| Conventional oxygen therapy | 0.15 (0.06, 0.38) | < 0.001 | 0.21 (0.07, 0.62) | 0.005a |

| Sedation treatment | 2.03 (0.88, 4.70) | 0.097 | ||

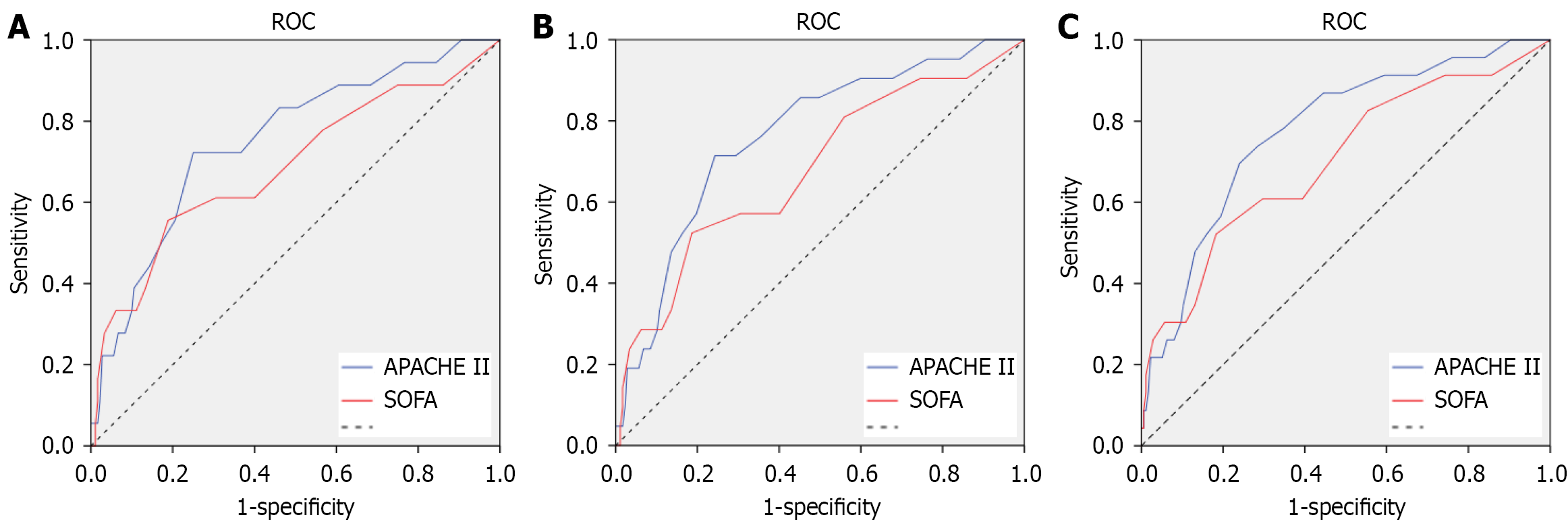

The multivariate analysis results indicated that the current data showed a lack of dependable predictors for short-term mortality of ICU admitted CRC patients. General functional status and disease severity score are commonly applied in clinical practice for evaluation of ICU patients. We therefore tested the predictive value of SOFA and APACHE II scores for short-term mortality of ICU admitted CRC patients. As shown in Figure 2 and Table 3, both scores showed moderate accuracy in predicting short-term mortality, with the highest area under the curve of time ROC at 0.797 when death within 80 days was predicted by the APACHE II score. These findings demonstrated that these scores may not be sufficient for the prognosis of ICU admitted CRC patients. Further exploration of predictors needs to be carried out in the future.

| Time periods | AUC | 95%CI |

| 30 days | ||

| SOFA | 0.708 | 0.550-0.865 |

| APACHE II | 0.779 | 0.6493-0.908 |

| 60 days | ||

| SOFA | 0.697 | 0.559-0.835 |

| APACHE II | 0.785 | 0.673-0.897 |

| 80 days | ||

| SOFA | 0.719 | 0.591-0.848 |

| APACHE II | 0.797 | 0.693-0.901 |

An analysis of data from 37 ICUs within specialized cancer hospitals identified 189 admissions for CRC over a two-month period. Following ICU care, the recorded 90-day mortality for these patients was 12.2%. Patients with 90-day mortality generally had more severe conditions before admission when compared to surviving patients, as well as more ICU complications and intensive treatment. Chemotherapy history, elective surgery and conventional oxygen therapy were the only significant associations identified in multivariate analysis. SOFA and APACHE II scores only had moderate predictive values for short-term mortality. These findings showed that ICU admitted CRC patients generally had a good survival prognosis; however, there is currently still a lack of dependable predictors for short-term mortality outcome.

CRC patients generally have good survival prognosis. A multi-national study with a large sample size identified a 5-year overall survival rate of 83.4% in screening diagnosed CRC patients[30]. The average in-hospital mortality was reported to be only 4.9%[31]. Specific data on ICU admitted CRC patients are rarely reported, a single center study suggested that a quarter of ICU admitted CRC patients died during hospitalization[29], which was comparable to 20%-30% overall in-hospital short-term mortality of ICU patients with solid tumors[32-34]. The 90-day mortality after ICU care of CRC patients was found to be 12.2% in the present study. These results again appear to suggest that CRC patients were among the lower risk populations even when intense clinical management is required. However, due to the cross-sectional nature of the current study, it may be premature to draw conclusions. The general prognosis of ICU admitted CRC patients, especially the stratified risks of patients admitted for different reasons, require further confirmation in future longitudinal studies.

Post-surgery care is the main reason for many CRC patients admitted to the ICU. Previous studies have found that the risk factors for planned and unplanned post-surgery admission to the ICU included older age, male gender, lower BMI, type 2 diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, and advanced tumor stages[35]. In this study, the majority of ICU admitted CRC patients were transferred from the operation room. Compared to those transferred from clinical wards, patients who received post-surgery care in the ICU, especially those with a planned transfer, had significantly better survival outcomes. A higher percentage of clinical ward transfer was found in deceased patients, indicating that an emergency during disease progression or treatment was more likely to be associated with mortality risk. A previous study showed that the main emergencies related to CRC included intestinal obstruction, hemorrhage, and perforation, with advanced age, ethnicity, comorbidities, and more advanced stage as associated factors[36]. The reviewed data did not include detailed descriptions of cancer-related causes of ICU admission, therefore the risk factors for more severe ICU conditions and higher mortality risks require further exploration in future studies.

Previous studies assessing risk factors for post-operative adverse outcomes in CRC patients have suggested multiple potential predictors. Malnutrition has been suggested to be an important factor. For example, the modified frailty index was suggested to predict adverse outcomes in colon cancer patients undergoing surgical intervention[26]. Subjective global assessment was among predictors of postoperative recovery and survival after CRC surgery[37,38]. Controlled nutritional status score was significantly associated with postoperative patient outcomes and complications, including polyacrylate polyalcohol copolymer[28]. The geriatric nutritional risk index combined with calf circumference is a good predictor of prognosis in patients undergoing surgery for gastric cancer or CRC[39]. Other suggested predictors included age, pre-existing cardiovascular disease or anemia, serum lactate and lactate dehydrogenase levels, and inflammatory markers[15,40-42]. In this study, no specific factors were identified to predict short-term mortality. These results may indicate that ICU admitted CRC patients, who were not only transferred for post-operative complication management, may have more complicated conditions and need to be assessed more carefully for risk stratification.

The prognosis of CRC in the ICU may be influenced by multiple factors. Generally, CRC prognosis is significantly affected by comorbidities and frailty[43]. Age is associated with increased in-hospital mortality[44]. Clinical symptoms and pathological factors significantly impact the prognosis of CRC. Factors associated with worse prognosis included tumor spread beyond the bowel wall and regional lymph node involvement[45], as well as poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas, lymphangitic type[46], while vegetant gross tumors, papillary microscopic forms, well to moderately differentiated tumors may be favorable predictors[47]. In addition, CRC treatment relies on pathological assessment of resected specimens. Molecular subtyping of CRC can enhance understanding of tumor biology and aid in personalizing treatment strategies[48]. Due to the limited sample size, detailed analysis of associated factors could not generate useful information facilitating personalized risk stratification and prognosis. More in-depth analysis is warranted in future studies.

There are some limitations in this study, for example, sample size and the completeness of available data. Moreover, due to limited data, we were unable to identify specific indicators for adverse prognosis of ICU admitted CRC patients. The correlations found in both univariate and multivariate analysis with mortality were mostly indicators of disease severity, such as treatment history and elective surgery which may indicate the manageability of the disease. More records of ICU complications and related treatment also may only reflect the seriousness of conditions on ICU admission. No specific predictor was identified from the current data. The prognosis evaluation may still depend on current available disease severity evaluation tools such as SOFA and APACHE II, although their predictive values were also moderate. However, given the scarcity of research focusing on this specific patient group, our study addresses a gap in the literature regarding the provision of further prognostic information on ICU-admitted CRC patients.

A low short-term mortality rate of ICU admitted CRC cancer patients was observed, which needs to be further confirmed by longitudinal studies with a larger sample size. Mortality risk was higher in patients transferred from clinical wards. The prognostic tools for these patients need to be further optimized.

| 1. | Koutsoukou A. Admission of critically ill patients with cancer to the ICU: many uncertainties remain. ESMO Open. 2017;2:e000105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Martos-Benítez FD, Soler-Morejón CD, Lara-Ponce KX, Orama-Requejo V, Burgos-Aragüez D, Larrondo-Muguercia H, Lespoir RW. Critically ill patients with cancer: A clinical perspective. World J Clin Oncol. 2020;11:809-835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Puxty K, McLoone P, Quasim T, Sloan B, Kinsella J, Morrison DS. Risk of Critical Illness Among Patients With Solid Cancers: A Population-Based Observational Study. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:1078-1085. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Azoulay E, Schellongowski P, Darmon M, Bauer PR, Benoit D, Depuydt P, Divatia JV, Lemiale V, van Vliet M, Meert AP, Mokart D, Pastores SM, Perner A, Pène F, Pickkers P, Puxty KA, Vincent F, Salluh J, Soubani AO, Antonelli M, Staudinger T, von Bergwelt-Baildon M, Soares M. The Intensive Care Medicine research agenda on critically ill oncology and hematology patients. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:1366-1382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Valley TS, Schutz A, Miller J, Miles L, Lipman K, Eaton TL, Kinni H, Cooke CR, Iwashyna TJ. Hospital factors that influence ICU admission decision-making: a qualitative study of eight hospitals. Intensive Care Med. 2023;49:505-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Toffart AC, Gonzalez F, Hamidfar-Roy R, Darrason M. [ICU admission for cancer patients with respiratory failure: An ethical dilemma]. Rev Mal Respir. 2023;40:692-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zampieri FG, Romano TG, Salluh JIF, Taniguchi LU, Mendes PV, Nassar AP Jr, Costa R, Viana WN, Maia MO, Lima MFA, Cappi SB, Carvalho AGR, De Marco FVC, Santino MS, Perecmanis E, Miranda FG, Ramos GV, Silva AR, Hoff PM, Bozza FA, Soares M. Trends in clinical profiles, organ support use and outcomes of patients with cancer requiring unplanned ICU admission: a multicenter cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47:170-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Epstein AS, Yang A, Colbert LE, Voigt LP, Meadows J, Goldberg JI, Saltz LB. Outcomes of ICU Admission of Patients With Progressive Metastatic Gastrointestinal Cancer. J Intensive Care Med. 2020;35:297-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kemoun G, Weiss E, El Houari L, Bonny V, Goury A, Caliez O, Picard B, Rudler M, Rhaiem R, Rebours V, Mayaux J, Bachet JB, Belin L, Demoule A, Decavèle M. Clinical features and outcomes of patients with pancreatic cancer requiring unplanned medical ICU admission: A retrospective multicenter study. Dig Liver Dis. 2024;56:514-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Xu ZY, Hao XY, Wu D, Song QY, Wang XX. Prognostic value of 11-factor modified frailty index in postoperative adverse outcomes of elderly gastric cancer patients in China. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2023;15:1093-1103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Siegel RL, Wagle NS, Cercek A, Smith RA, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73:233-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1839] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 12. | World Health Organization. Colorectal cancer. [cited 15 February 2025]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/colorectal-cancer. |

| 13. | Wang W, Yin P, Liu YN, Liu JM, Wang LJ, Qi JL, You JL, Lin L, Meng SD, Wang FX, Zhou MG. Mortality and years of life lost of colorectal cancer in China, 2005-2020: findings from the national mortality surveillance system. Chin Med J (Engl). 2021;134:1933-1940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Paynter JA, Doherty Z, Lee CHA, Qin KR, Brennan J, Pilcher D. Comparison of colorectal cancer surgery patients in intensive care between rural and metropolitan hospitals in Australia: a national cohort study. Ann Coloproctol. 2025;41:68-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wang X, Li C, Li M, Zeng X, Mu J, Li Y. Clinical significance of serum lactate and lactate dehydrogenase levels for disease severity and clinical outcomes in patients with colorectal cancer admitted to the intensive care unit. Heliyon. 2024;10:e23608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Liu W, Zhou D, Zhang L, Huang M, Quan R, Xia R, Ye Y, Zhang G, Shen Z; Cancer Critical Care Medicine Committee of the Chinese Anti-Cancer Association. Characteristics and outcomes of cancer patients admitted to intensive care units in cancer specialized hospitals in China. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2024;150:205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Puxty K, McLoone P, Quasim T, Sloan B, Kinsella J, Morrison DS. Characteristics and Outcomes of Surgical Patients With Solid Cancers Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:834-840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Darmon M, Azoulay E. Critical care management of cancer patients: cause for optimism and need for objectivity. Curr Opin Oncol. 2009;21:318-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mendoza V, Lee A, Marik PE. The hospital-survival and prognostic factors of patients with solid tumors admitted to an ICU. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2008;25:240-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Soubani AO. Critical Care Prognosis and Outcomes in Patients with Cancer. Clin Chest Med. 2017;38:333-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Guo C, Pan J, Tian S, Gao Y. Using machine learning algorithms to predict 28-day mortality in critically ill elderly patients with colorectal cancer. J Int Med Res. 2023;51:3000605231198725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wang L, Wu Y, Deng L, Tian X, Ma J. Construction and validation of a risk prediction model for postoperative ICU admission in patients with colorectal cancer: clinical prediction model study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2024;24:222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Tan JKH, Koh WL, Peh CH, Lee AWX, Lau J, Chee C, Tan KK. Surgical High Dependency Admissions after Elective Laparoscopic Colorectal Resections: Is It Truly Necessary? J Intensive Care Med. 2024;39:153-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Peters F, Hohenstein S, Bollmann A, Kuhlen R, Ritz JP. The Postoperative Utilization of Intensive Care Beds After Visceral Surgery Procedures. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2023;120:633-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | de Nes LCF, Hannink G, 't Lam-Boer J, Hugen N, Verhoeven RH, de Wilt JHW; Dutch Colorectal Audit Group. Postoperative mortality risk assessment in colorectal cancer: development and validation of a clinical prediction model using data from the Dutch ColoRectal Audit. BJS Open. 2022;6:zrac014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Pandit V, Khan M, Martinez C, Jehan F, Zeeshan M, Koblinski J, Hamidi M, Omesieta P, Osuchukwu O, Nfonsam V. A modified frailty index predicts adverse outcomes among patients with colon cancer undergoing surgical intervention. Am J Surg. 2018;216:1090-1094. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Park JH, Kim DH, Kim BR, Kim YW. The American Society of Anesthesiologists score influences on postoperative complications and total hospital charges after laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e0653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Li Y, Nie C, Li N, Liang J, Su N, Yang C. The association between controlling nutritional status and postoperative pulmonary complications in patients with colorectal cancer. Front Nutr. 2024;11:1425956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Camus MF, Ameye L, Berghmans T, Paesmans M, Sculier JP, Meert AP. Rate and patterns of ICU admission among colorectal cancer patients: a single-center experience. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:1779-1785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Cardoso R, Guo F, Heisser T, De Schutter H, Van Damme N, Nilbert MC, Christensen J, Bouvier AM, Bouvier V, Launoy G, Woronoff AS, Cariou M, Robaszkiewicz M, Delafosse P, Poncet F, Walsh PM, Senore C, Rosso S, Lemmens VEPP, Elferink MAG, Tomšič S, Žagar T, Marques ALM, Marcos-Gragera R, Puigdemont M, Galceran J, Carulla M, Sánchez-Gil A, Chirlaque MD, Hoffmeister M, Brenner H. Overall and stage-specific survival of patients with screen-detected colorectal cancer in European countries: A population-based study in 9 countries. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2022;21:100458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Grewal US, Patel H, Gaddam SJ, Sheth AR, Garikipati SC, Mills GM. National trends in hospitalizations among patients with colorectal cancer in the United States. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2022;35:153-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Ostermann M, Ferrando-Vivas P, Gore C, Power S, Harrison D. Characteristics and Outcome of Cancer Patients Admitted to the ICU in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland and National Trends Between 1997 and 2013. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:1668-1676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Martos-Benítez FD, Soto-García A, Gutiérrez-Noyola A. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of cancer patients requiring intensive care unit admission: a prospective study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2018;144:717-723. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Puxty K, McLoone P, Quasim T, Kinsella J, Morrison D. Survival in solid cancer patients following intensive care unit admission. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:1409-1428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Liu XY, Yuan C, Kang B, Cheng YX, Tao W, Zhang B, Wei ZQ, Peng D. Predictors associated with planned and unplanned admission to intensive care units after colorectal cancer surgery: a retrospective study. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30:5099-5105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Menegozzo CAM, Teixeira-Júnior F, Couto-Netto SDD, Martins-Júnior O, Bernini CO, Utiyama EM. Outcomes of Elderly Patients Undergoing Emergency Surgery for Complicated Colorectal Cancer: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2019;74:e1074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Teraishi F, Yoshida Y, Shoji R, Kanaya N, Matsumi Y, Shigeyasu K, Kondo Y, Kagawa S, Tamura R, Matsuoka Y, Morimatsu H, Mitsuhashi T, Fujiwara T. Subjective global assessment for nutritional screening and its impact on surgical outcomes: A prospective study in older patients with colorectal cancer. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2024;409:356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Erdim A, Aktan AÖ. Evaluation of perioperative nutritional status with subjective global assessment method in patients undergoing gastrointestinal cancer surgery. Turk J Surg. 2017;33:253-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Zheng X, Shi JY, Wang ZW, Ruan GT, Ge YZ, Lin SQ, Liu CA, Chen Y, Xie HL, Song MM, Liu T, Yang M, Liu XY, Deng L, Cong MH, Shi HP. Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index Combined with Calf Circumference Can be a Good Predictor of Prognosis in Patients Undergoing Surgery for Gastric or Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Control. 2024;31:10732748241230888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Niu R, Jiang Y, Bi Z, Zhang H, Mei X, Bi J, Xing W, Guo W, Liang J. The effect of cardiovascular disease on the perioperative period of radical surgery in elderly rectal cancer. BMC Gastroenterol. 2024;24:256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Deng Y, Chen Q, Chen J, Zhang Y, Zhao J, Bi X, Li Z, Zhang Y, Huang Z, Cai J, Zhao H. An elevated preoperative cholesterol-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts unfavourable outcomes in colorectal cancer liver metastasis patients receiving simultaneous resections: a retrospective study. BMC Surg. 2023;23:131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Sonal S, Schneider D, Boudreau C, Kunitake H, Goldstone RN, Bordeianou LG, Cauley CE, Francone TD, Ricciardi R, Berger DL. Patient Factors Affecting Inpatient Mortality Following Colorectal Cancer Resection. Am Surg. 2023;89:5806-5812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Boakye D, Rillmann B, Walter V, Jansen L, Hoffmeister M, Brenner H. Impact of comorbidity and frailty on prognosis in colorectal cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;64:30-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | McGillicuddy EA, Schuster KM, Davis KA, Longo WE. Factors predicting morbidity and mortality in emergency colorectal procedures in elderly patients. Arch Surg. 2009;144:1157-1162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Szynglarewicz B, Grzebieniak Z, Forgacz J, Pudełko M, Rapała M. [Prognostic significance of clinical and pathomorphological factors in colorectal cancer: a uni- and multivariate analysis]. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2004;17:586-589. [PubMed] |

| 46. | Ogawa M, Watanabe M, Eto K, Kosuge M, Yamagata T, Kobayashi T, Yamazaki K, Anazawa S, Yanaga K. Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of the colon and rectum: clinical characteristics. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:907-911. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Vasile L, Olaru A, Munteanu M, Pleşea IE, Surlin V, Tudoraşcu C. Prognosis of colorectal cancer: clinical, pathological and therapeutic correlation. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2012;53:383-391. [PubMed] |

| 48. | Wang C, Zhang H, Liu Y, Wang Y, Hu H, Wang G. Molecular subtyping in colorectal cancer: A bridge to personalized therapy (Review). Oncol Lett. 2023;25:230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/