Published online Mar 15, 2024. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v16.i3.1076

Peer-review started: October 13, 2023

First decision: December 15, 2023

Revised: December 26, 2023

Accepted: January 24, 2024

Article in press: January 24, 2024

Published online: March 15, 2024

Processing time: 150 Days and 22.2 Hours

Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (GEP-NENs) are rare tumors, often diagnosed in an advanced stage when curative treatment is impossible and grueling symptoms related to vasoactive substance release by tumor cells affect patients’ quality of life. Cardiovascular complications of GEP-NENs, primarily tricuspid and pulmonary valve disease, and right-sided heart failure, are the leading cause of death, even compared to metastatic disease.

We present a case of a 35-year-old patient with progressive dyspnea, back pain, polyneuropathic leg pain, and nocturnal diarrhea lasting for a decade before the diagnosis of neuroendocrine carcinoma of unknown primary with extensive liver metastases. During the initial presentation, serum biomarkers were not evaluated, and the patient received five cycles of doxorubicin, which he did not tolerate well, so he refused further therapy and was lost to follow-up. After 10 years, he presented to the emergency room with signs and symptoms of right-sided heart failure. Panneuroendocrine markers, serum chromogranin A, and urinary 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid were extremely elevated (900 ng/mL and 2178 µmol/L), and transabdominal ultrasound confirmed hepatic metastases. Computed tomo

Carcinoid heart disease occurs with carcinoid syndrome related to advanced neuroendocrine tumors, usually with liver metastases, which manifests as right-sided heart valve dysfunction leading to right-sided heart failure. Carcinoid heart disease and tumor burden are major prognostic factors of poor survival. Therefore, they must be actively sought by available biochemical markers and imaging techniques. Moreover, imaging techniques aiding tumor detection and staging, somatostatin receptor positron emission tomography/CT, and CT or magnetic resonance imaging, should be performed at the time of diagnosis and in 3- to 6-mo intervals to determine tumor growth rate and assess the possibility of locoregional therapy and/or palliative surgery. Valve replacement at the onset of symptoms or right ventricular dysfunction may be considered, while any delay can worsen right-sided ventricular failure.

Core Tip: Cardiovascular complications of neuroendocrine neoplasms are the leading cause of death, even compared to metastatic disease. Early detection of right ventricular dysfunction and changes in the tricuspid valve are crucial. Here, we present a patient with advanced carcinoid heart disease with a poor prognosis. Considering current recommendations, it seems reasonable to search for subclinical right-sided heart damage by determining N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide in patients with elevated biomarker values and neuroendocrine tumors, resulting in earlier diagnosis and treatment.

- Citation: Bulj N, Tomasic V, Cigrovski Berkovic M. Managing end-stage carcinoid heart disease: A case report and literature review. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2024; 16(3): 1076-1083

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v16/i3/1076.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v16.i3.1076

Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (GEP-NENs) are frequently diagnosed in an advanced stage. This is mostly due to nonspecific early symptoms and often small and easily unforeseen primary tumors, contributed by limited knowledge of this relatively unknown subject[1]. Metastases of GEP-NENs are primarily in the liver, regional lymph nodes, and bones. However, released hormones, amines, and cytokines can affect almost every organ and generate numerous grueling symptoms. Carcinoid syndrome (CS), presenting as diarrhea, flushing, and abdominal pain caused by the systemic release of serotonin, is seen in up to 30% of patients as an initial tumor manifestation[2,3]. The cardiac manifestation of serotonin hyperproduction, carcinoid heart disease (CHD), develops in up to 70% of patients with CS due to right-sided valve, papillary muscle, and chordae tendineae fibrosis, initiated by the actions of serotonin on receptors expressed on cardiac valves. This negatively affects patients’ quality of life and survival[4,5].

Although some diagnostic tools are very effective, it is still a challenge to diagnose primary GEP-NENs in a timely manner and select patients at risk for rare neuroendocrine tumor-driven pathologies such as CHD[6,7]. In cases of CHD, surgical valve replacement (previously reserved only for severely symptomatic patients) is indicated for mild symptoms due to the progression of heart failure and increase in overall mortality[8]. Moreover, different tumor debulking procedures and cytoreductive surgery are considered in addition to pharmacotherapy for symptom control and improvement of patient survival[9].

We present a case of a 35-year-old patient seen for progressive dyspnea, back pain, polyneuropathic leg pain, and nocturnal diarrhea lasting a decade before an accurate diagnosis.

A young male patient was admitted to the emergency department in 2010 due to progressive dyspnea, back pain, polyneuropathic leg pain, and nocturnal diarrhea. In 2000, he complained of leg and lower back numbness. A transabdominal ultrasound showed liver metastases. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) confirmed liver metastases without detection of the primary tumor. Fine needle aspiration (FNA) of a liver lesion revealed metastases of neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC). The common neuroendocrine markers were not evaluated, and the patient refused further gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopic evaluation. He was referred to an oncologist and received five cycles of doxorubicin. Due to nausea and treatment intolerance, he refused further therapy and was lost to follow-up. Meanwhile, he sought out treatments such as bioenergy and unknown herbal substances.

At the time the patient first came, he was dyspneic, plethoric, and cyanotic with bluish-red skin. The transabdominal ultrasound confirmed hepatic metastases; therefore we expanded further diagnostic workup.

In 2000, the patient initially complained of leg and lower back numbness. A transabdominal ultrasound showed liver metastases. An abdominal CT confirmed the liver metastases without detection of the primary tumor. FNA of a liver lesion revealed metastases of an NEC. The common neuroendocrine markers were not evaluated, and the patient refused further GI endoscopic evaluation.

The patient was referred to an oncologist and received five cycles of doxorubicin. Due to nausea and treatment intolerance, he refused further therapy, and for years, there was no medical follow-up. Meanwhile, he sought out treatments such as bioenergy and unknown herbal substances.

A precordial systolic murmur II/VI was detected, and heart sounds were subtle. The liver was enlarged, and his legs were swollen with trophic skin changes.

Panneuroendocrine markers, serum chromogranin A (CgA) 900 ng/mL (normal range < 90 ng/mL, and urinary 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) 2178 µmol/L (normal 78 < µmol/L) came back elevated. He was hypoglycemic (blood glucose of 2.8 mmol/L), hypoalbuminemic, and anemic. His serum calcium levels, insulin, and C-peptide levels were normal.

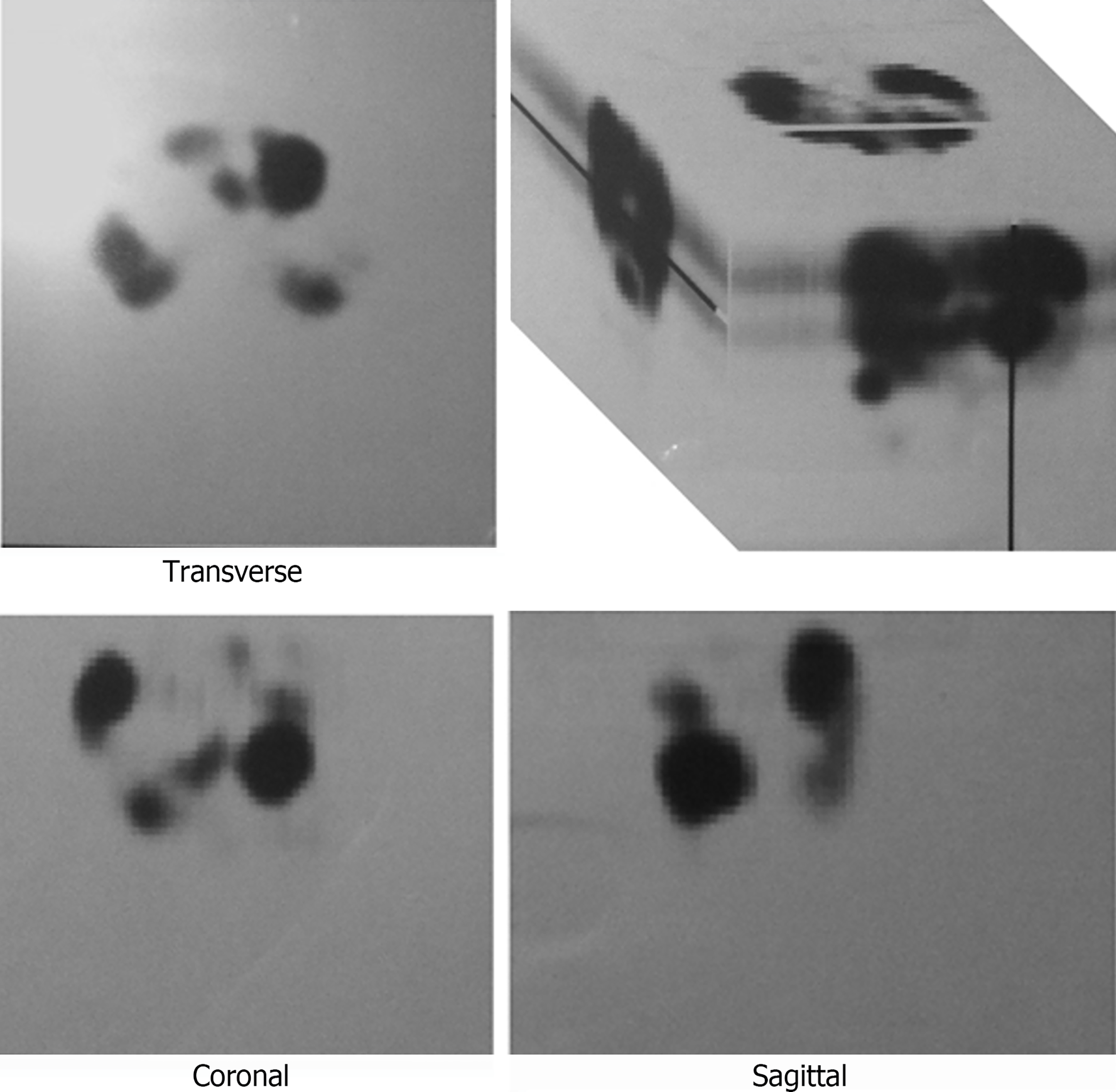

The transabdominal ultrasound confirmed hepatic metastases, so further imaging was scheduled. CT showed liver involvement with hypervascular metastatic masses up to 6 cm in diameter, ascites, and metastases to the mesenteric lymph nodes and pelvic bones. The pancreas and suprarenal glands were normal, and the primary tumor location could not be identified. Whole-body scintigraphy and thoracic and abdominal single-photon emission computerized tomography (SPECT) imaging at 4 and 24 h after intravenous injection of 111 MBq 111In-pentetreotide showed diffusely intense accumulation of the radiopharmaceutical (RF) in the heart and several lesions in the thoracic spine. Multiple lesions with increased accumulation of RF were found in the enlarged liver, intestine (as this could be the site of the primary tumor), duodenum, and ascendant colon (similar findings on both days of imaging), paraaortic lymph nodes, and one focal lesion within the pelvis. All lesions were seen better on the 24-h planar scan and SPECT (Figure 1).

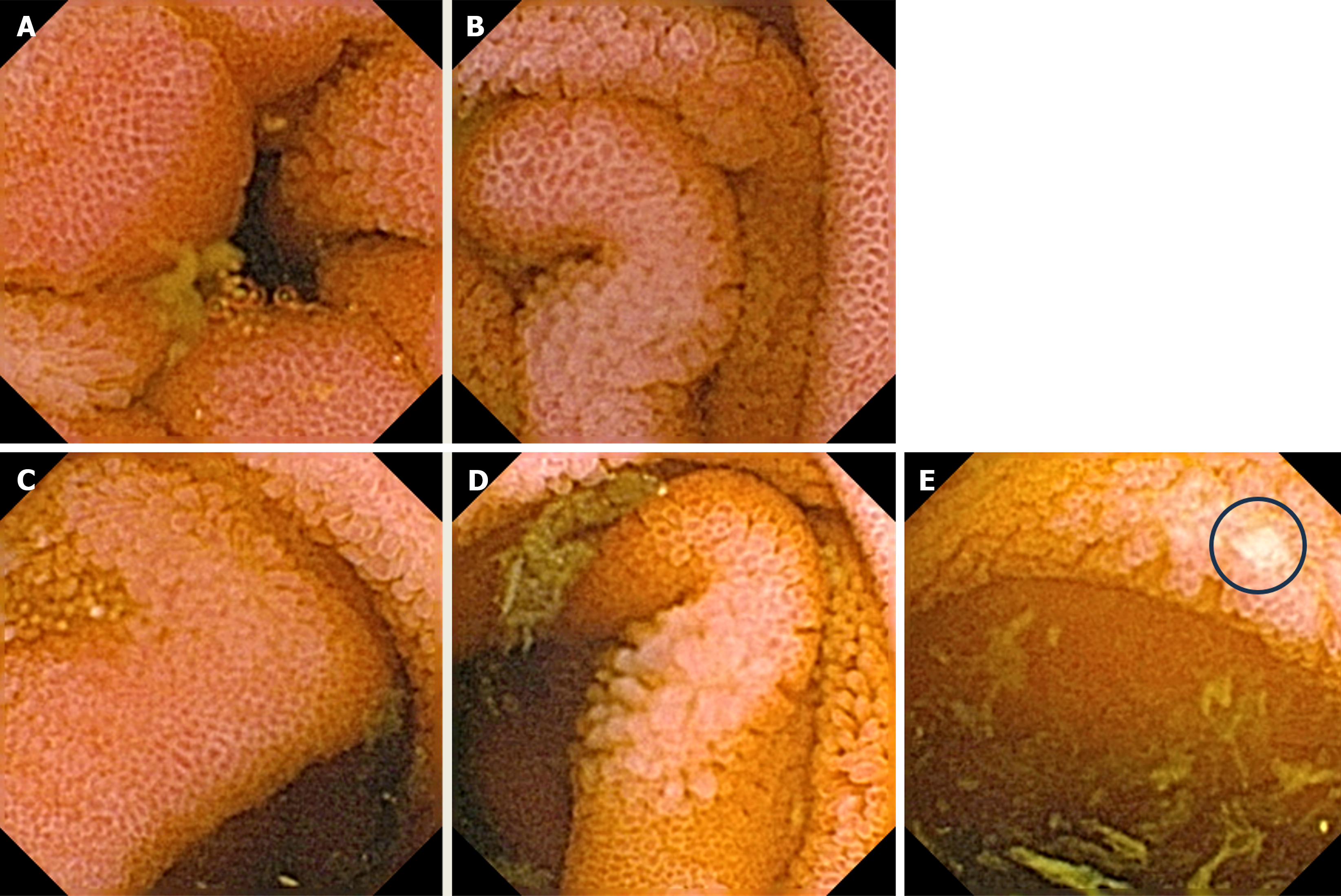

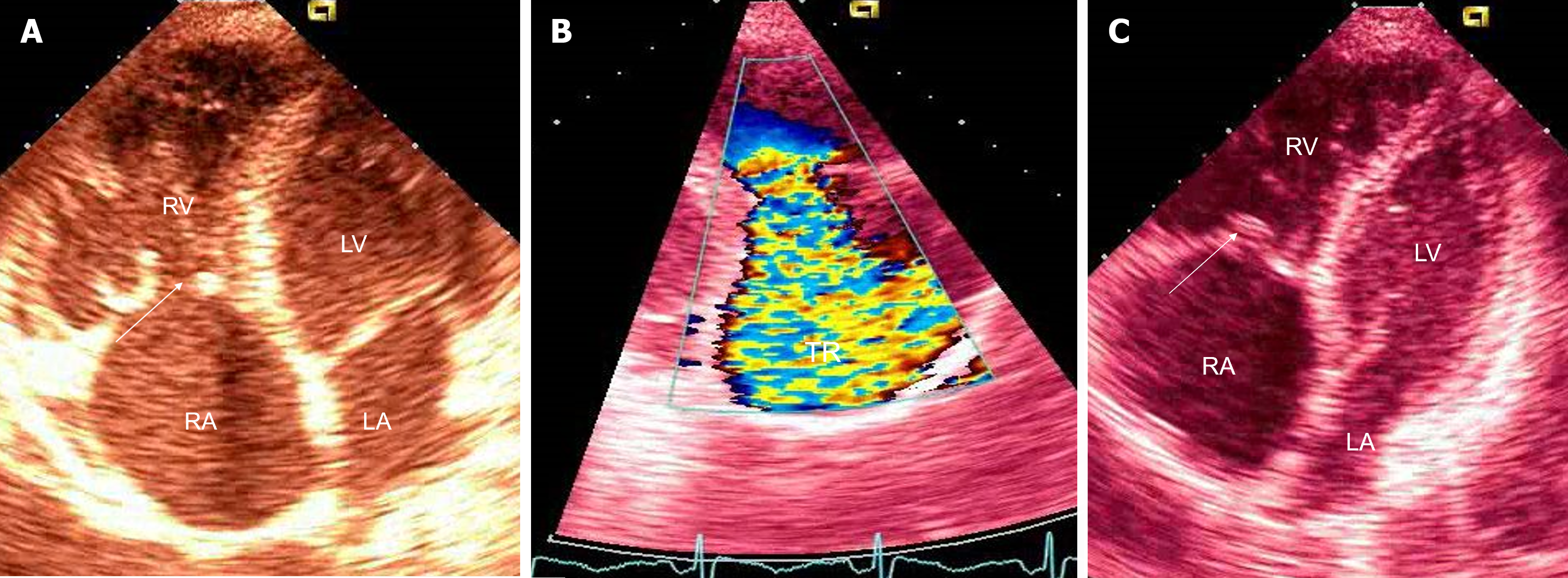

Upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract endoscopy indicated chronic Helicobacter pylori-negative gastritis and a complete colonoscopy was normal. A capsule endoscopy revealed long and diffuse segments of erythematous and edematous ileal mucosa, with a granular appearance, villous denudation, one erosion, and patchy areas of edematous “remaining” villi. No mucosal (flat or protruding), submucosal lesions, stenosis, or intraluminal bleeding was visualized (Figure 2). The patient refused an enteroscopy, planned for obtaining histology specimens. Due to progressive dyspnea and suspected carcinoid heart involvement, a standard transthoracic echocardiogram revealed typical manifestations of CHD. The right atrium and ventricle were dilated with typical thickening and retraction of immobile tricuspid valve leaflets associated with severe tricuspid regurgitation. Signs of mild tricuspid stenosis (area of 2.2 cm2) were observed. Coexisting pulmonary valve disease, with predominant stenosis of a gradient up to 33 mmHg, was also noted. The pericardium was thickened with a small pericardial effusion and signs of diastolic filling impairment with paradoxical movement of the interventricular septum. The inferior vena cava and hepatic veins were dilated without any inspiratory variations. The unexpected and unusual finding was apical displacement of the tricuspid valve (24 mm above the mitral ring), as seen in type 1 Ebstein’s anomaly (Figure 3).

The patient was diagnosed with CHD with right-sided heart failure due to metastatic neuroendocrine neoplasm of an unknown primary site.

Intramuscular octreotide acetate (Sandostatin LAR) 20 mg in monthly intervals was started, but without significant improvement initially (biochemical or clinical). The dose was increased to 80 mg over 12 mo. The drug was well tolerated even at a high dose, and laboratory findings had regressive dynamics (CgA at 3, 6, 9, and 12 mo were 800, 650, 500, and 350 ng/mL respectively; 5-HIAA at 3, 6, 9, and 12 mo 2005, 1880, 1650, and 950 µmol/L, respectively). Although cardiac symptomatology persisted, it did not progress. The patient was not a good candidate for valve replacement due to his right-sided heart dysfunction, and he refused ablative procedures for liver metastases. He did not want chemotherapy to be reinitiated and refused irradiation of bone metastases.

The patient died in 2014.

This patient is a typical example of a neglected/uncared-for GEP-NEN patient, even though newer treatment options provide a relatively good prognosis[10,11]. Carcinoid heart involvement is characteristic for 40%-50% of patients with a full-blown picture of CS, and when present, it is more likely to be the cause of death rather than metastatic disease. It typically affects the right side of the heart, with tricuspid and pulmonary valve involvement as a universal finding[12]. In the pathogenesis of right-sided heart fibrosis, growth factors, such as transforming growth factor beta and serotonin, seem crucial. Several studies have shown that 5-HIAA (a serotonin metabolite) levels are higher in the urine with fully developed CHD or with a higher risk of heart involvement. A specific, prospective follow-up of 252 patients with CS, after a median of 29 mo, showed that urinary 5-HIAA level ≥ 300 μmol/24 h is an independent predictor of CHD[13].

In addition, a significant parameter differentiating between patients with poor (average of 6 mo) or good (average of 50 mo) survival following diagnosis of CHD is the time following the initial GEP-NEN diagnosis[14]. An asymptomatic or subclinical CHD could be present during CS with a negative impact on the disease progression and clinical deterioration. Therefore, it is recommended to have a baseline evaluation of N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) at the time of diagnosis of CS[15]. Monitoring of NT-proBNP followed by echocardiography in patients with CS, especially with high urinary 5-HIAA levels, could emerge as a new screening and follow-up recommendation[15,16]. Once detected, elevated levels of NT-proNP should facilitate echocardiography and other imaging modalities (such as cardiac CT and magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) to detect early cardiac damage and valvular disease. Unfortunately, in this case, during the initial patient evaluation, routine NT-proBNP measurements were not available, and a proper risk stratification was not possible. To date, the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society recommends tumor markers (CgA, 5-HIAA) and NT-proBNP to be evaluated annually or semiannually in GEP-NEN patients[17,18]. Although the optimal timing of surgery, depending on the severity of valve dysfunction and symptoms, has not yet been defined, based on newer data, valve replacement surgery at the onset of symptoms or right ventricular dysfunction may be considered, while any delay can result in worsening of right-sided ventricular failure[19].

In addition, side effects of pharmacological treatment, especially chemotherapy, in case of metastatic NEC, must be considered in patients with CS[20-23]. Although doxorubicin has a high potential for cardiotoxicity, its significance was not clear in this patient. The left-sided heart function of this patient was preserved, so it is not entirely clear whether prior treatment with this drug facilitated or accelerated the deterioration of the right-sided heart function.

To optimize the surgical outcome and reduce complications, it is important to control the circulating vasoactive carcinoid tumor substances before heart valve replacement[24,25]. Concerning the aforementioned, the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) recommends somatostatin analogue therapy as a first-line option in patients with CS as it diminishes tumor progression[26]. Unfortunately, in this case, a somatostatin analogue was not an initial therapy, but rather a late, nonetheless achieving biochemical and symptomatic improvement. Further pharmacological treatment, especially in the case of refractory CS, remains a matter of debate. The data on chemotherapy are historical and usually demonstrate a reduction of urinary 5-HIAA levels. On the other hand, evidence of its usefulness in CS-related outcomes, including CHD, is lacking and inconsistent[20].

In addition, it is of the utmost importance to stage the tumor properly, and if possible, to find the primary site while different extents of surgical treatment are possible and a reduction in tumor load can result in better biochemical control and favorable survival[18]. Until precise evidence-based recommendations become available, the order of surgical approach (surgery based on tumor operability/metastatic type with valve replacement surgery) in patients with carcinoid heart involvement is still a matter of debate. It should be decided individually, focusing on the severity and symptoms of CHD. According to current, mainly retrospective studies, valve replacement might be considered before cytoreductive surgery in patients with progressive CHD, while the evidence supporting the role of hepatic resection first to improve the prognosis of patients with CHD is scarce[27].

For staging purposes, this patient had a CT, which could not identify the primary tumor. Given the superiority of an MRI for examining the liver and pancreas, one could argue, in concordance with recent ESMO clinical practice guidelines, that if this patient in 2010 was additionally evaluated with an MRI, perhaps the primary GEP-NEN would be localized. Endoscopic ultrasound, with FNA or fine needle biopsy, is currently the best method for the visualization of small pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (NETs). This patient was not evaluated with either of these methods. The diagnosis of GEP-NEN in this patient was achieved with an FNA cytology review of the liver metastases. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound with biopsy for histology in 2023 gives added benefit to split the heterogeneous G3 GEP-NENs into well-differentiated NET G3 and poorly differentiated NEC G3 according to the 2019 World Health Organization classification. These two diverse classes of GEP-NENs have clear prognostic differences and could affect surgical approach (debulking surgery/palliative resection) and/or locoregional treatments[28].

During diagnostic and follow-ups, patients with NEC with unknown primary sites should undergo functional imaging. Historically, scintigraphy using 111 In-pentetreotide (Ostreoscan), was most important and useful for identifying and staging tumors containing somatostatin receptor (SSTR) subtypes 2 and 5. It is a highly sensitive and specific method for carcinoid tumors, both functioning and nonfunctioning. In patients with asymptomatic GI NETs, the diagnostic sensitivity is 80%-90%, even more than 90% for symptomatic CS[29]. Unfortunately, Octreoscan can miss a primary tumor in a significant proportion of patients with metastatic disease, which was also the case in our patient[30,31].

Compared to Ostreoscan, 68Ga-DOTATATE can identify more lesions, and therefore, aid in the management of GEP-NEN patients. Furthermore, positron emission tomography (PET)/MRI with 68Ga-DOTATOC may be superior to PET/CT in guiding the management of GEP-NENs, especially in the precise evaluation of hepatic tumor load[32]. A 2017 study of 40 patients with metastatic GEP-NENs, who had undergone CT or MRI but still had an unknown primary tumor location, showed that 68Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT could effectively localize the primary tumor to facilitate treatment[33].

In cases of metastatic carcinoid tumors, primary lesions are usually located in the jejuno/ileal region, and endoscopic procedures are of the utmost importance while they offer tissue biopsy and pathohistological assessment. In this case, the patient had an interesting capsule finding, which prompted further enteroscopy. This, similar to the measurements of specific tumor markers, was unfortunately initially omitted, but one might speculate that reduction of tumor burden and/or removal of the primary tumor would be beneficial for symptom relief and attenuation of the disease progression.

CHD is a complication occurring in patients with CS related to advanced NETs, usually with liver metastases, which manifests as right-sided heart valve dysfunction leading to right-sided heart failure. CHD, together with tumor burden, are major prognostic indicators of reduced survival. Therefore, they must be actively sought by available biochemical markers and imaging techniques in patients with CS, even though they are not present from the beginning of the disease, at the time of diagnosis, or are clinically insignificant. The most useful marker is urinary 5-HIAA, and its increase above ≥ 300 μmol/24 h, together with NT-proBNP > 260 pg/mL, necessitates further echocardiography evaluation. Moreover, imaging techniques aiding tumor detection and staging, SSTR PET/CT and CT or MRI, should be performed at the time of diagnosis and then on a 3- to 6-mo interval to determine tumor growth rate and assess the possibility of loco-regional therapy and/or palliative surgery. Cytoreductive surgery might be prudent and followed with valve replacement surgery, especially in more severe forms of CHD. First-line pharmacotherapy includes somatostatin analogs with a dose escalation until symptom relief is achieved. In cases of refractory CS, defined by persisting symptoms and increasing or persistently high urinary 5-HIAA levels despite using maximum labeled doses of somatostatin analogs, optimal subsequent treatment options still need to be determined.

| 1. | Fottner C, Ferrata M, Weber MM. Hormone secreting gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasias (GEP-NEN): When to consider, how to diagnose? Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2017;18:393-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Pinchot SN, Holen K, Sippel RS, Chen H. Carcinoid tumors. Oncologist. 2008;13:1255-1269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Oleinikov K, Korach A, Planer D, Gilon D, Grozinsky-Glasberg S. Update in carcinoid heart disease - the heart of the matter. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2021;22:553-561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ram P, Penalver JL, Lo KBU, Rangaswami J, Pressman GS. Carcinoid Heart Disease: Review of Current Knowledge. Tex Heart Inst J. 2019;46:21-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Palaniswamy C, Frishman WH, Aronow WS. Carcinoid heart disease. Cardiol Rev. 2012;20:167-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Townsend A, Price T, Yeend S, Pittman K, Patterson K, Luke C. Metastatic carcinoid tumor: changing patterns of care over two decades. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:195-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Grundmann E, Curioni-Fontecedro A, Christ E, Siebenhüner AR. Outcome of carcinoid heart syndrome in patients enrolled in the SwissNet cohort. BMC Cancer. 2023;23:338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Takahashi H, Okita Y. Cardiac surgery for carcinoid heart disease. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;59:777-779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kupietzky A, Dover R, Mazeh H. Surgical aspects of small intestinal neuroendocrine tumors. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2023;15:566-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ahmed A, Turner G, King B, Jones L, Culliford D, McCance D, Ardill J, Johnston BT, Poston G, Rees M, Buxton-Thomas M, Caplin M, Ramage JK. Midgut neuroendocrine tumours with liver metastases: results of the UKINETS study. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2009;16:885-894. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jann H, Roll S, Couvelard A, Hentic O, Pavel M, Müller-Nordhorn J, Koch M, Röcken C, Rindi G, Ruszniewski P, Wiedenmann B, Pape UF. Neuroendocrine tumors of midgut and hindgut origin: tumor-node-metastasis classification determines clinical outcome. Cancer. 2011;117:3332-3341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Dero I, De Pauw M, Borbath I, Delaunoit T, Demetter P, Demolin G, Hendlisz A, Pattyn P, Pauwels S, Roeyen G, Van Cutsem E, Van Hootegem P, Van Laethem JL, Verslype C, Peeters M. Carcinoid heart disease--a hidden complication of neuroendocrine tumours. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2009;72:34-38. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Bhattacharyya S, Toumpanakis C, Chilkunda D, Caplin ME, Davar J. Risk factors for the development and progression of carcinoid heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:1221-1226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Uema D, Alves C, Mesquita M, Nuñez JE, Siepmann T, Angel M, Rego JFM, Weschenfelder R, Rocha Filho DR, Costa FP, Barros M, O'Connor JM, Illigens BM, Riechelmann RP. Carcinoid Heart Disease and Decreased Overall Survival among Patients with Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Retrospective Multicenter Latin American Cohort Study. J Clin Med. 2019;8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Davar J, Connolly HM, Caplin ME, Pavel M, Zacks J, Bhattacharyya S, Cuthbertson DJ, Dobson R, Grozinsky-Glasberg S, Steeds RP, Dreyfus G, Pellikka PA, Toumpanakis C. Diagnosing and Managing Carcinoid Heart Disease in Patients With Neuroendocrine Tumors: An Expert Statement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:1288-1304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Fijalkowski R, Reher D, Rinke A, Gress TM, Schrader J, Baum RP, Kaemmerer D, Hörsch D. Clinical Features and Prognosis of Patients with Carcinoid Syndrome and Carcinoid Heart Disease: A Retrospective Multicentric Study of 276 Patients. Neuroendocrinology. 2022;112:547-554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Knigge U, Capdevila J, Bartsch DK, Baudin E, Falkerby J, Kianmanesh R, Kos-Kudla B, Niederle B, Nieveen van Dijkum E, O'Toole D, Pascher A, Reed N, Sundin A, Vullierme MP; Antibes Consensus Conference Participants; Antibes Consensus Conference participants. ENETS Consensus Recommendations for the Standards of Care in Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Follow-Up and Documentation. Neuroendocrinology. 2017;105:310-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Pavel M, Baudin E, Couvelard A, Krenning E, Öberg K, Steinmüller T, Anlauf M, Wiedenmann B, Salazar R; Barcelona Consensus Conference participants. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the management of patients with liver and other distant metastases from neuroendocrine neoplasms of foregut, midgut, hindgut, and unknown primary. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;95:157-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 608] [Cited by in RCA: 608] [Article Influence: 43.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bhattacharyya S, Raja SG, Toumpanakis C, Caplin ME, Dreyfus GD, Davar J. Outcomes, risks and complications of cardiac surgery for carcinoid heart disease. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;40:168-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Pavel ME, Baum U, Hahn EG, Hensen J. Doxorubicin and streptozotocin after failed biotherapy of neuroendocrine tumors. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2005;35:179-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Rogers JE, Lam M, Halperin DM, Dagohoy CG, Yao JC, Dasari A. Fluorouracil, Doxorubicin with Streptozocin and Subsequent Therapies in Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Neuroendocrinology. 2022;112:34-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hijioka S, Morizane C, Ikeda M, Ishii H, Okusaka T, Furuse J. Current status of medical treatment for gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms and future perspectives. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2021;51:1185-1196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Das S, Al-Toubah T, Strosberg J. Chemotherapy in Neuroendocrine Tumors. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gustafsson BI, Hauso O, Drozdov I, Kidd M, Modlin IM. Carcinoid heart disease. Int J Cardiol. 2008;129:318-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hofland J, Herrera-Martínez AD, Zandee WT, de Herder WW. Management of carcinoid syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2019;26:R145-R156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Pavel M, Öberg K, Falconi M, Krenning EP, Sundin A, Perren A, Berruti A; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:844-860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 465] [Cited by in RCA: 794] [Article Influence: 132.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kaltsas G, Caplin M, Davies P, Ferone D, Garcia-Carbonero R, Grozinsky-Glasberg S, Hörsch D, Tiensuu Janson E, Kianmanesh R, Kos-Kudla B, Pavel M, Rinke A, Falconi M, de Herder WW; Antibes Consensus Conference participants. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the Standards of Care in Neuroendocrine Tumors: Pre- and Perioperative Therapy in Patients with Neuroendocrine Tumors. Neuroendocrinology. 2017;105:245-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Assarzadegan N, Montgomery E. What is New in the 2019 World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumors of the Digestive System: Review of Selected Updates on Neuroendocrine Neoplasms, Appendiceal Tumors, and Molecular Testing. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2021;145:664-677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 26.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lu SJ, Gnanasegaran G, Buscombe J, Navalkissoor S. Single photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography in the evaluation of neuroendocrine tumours: a review of the literature. Nucl Med Commun. 2013;34:98-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Olsen JO, Pozderac RV, Hinkle G, Hill T, O'Dorisio TM, Schirmer WJ, Ellison EC, O'Dorisio MS. Somatostatin receptor imaging of neuroendocrine tumors with indium-111 pentetreotide (Octreoscan). Semin Nucl Med. 1995;25:251-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Dahdaleh FS, Lorenzen A, Rajput M, Carr JC, Liao J, Menda Y, O'Dorisio TM, Howe JR. The value of preoperative imaging in small bowel neuroendocrine tumors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1912-1917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Fang JM, Li J, Shi J. An update on the diagnosis of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:1009-1023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (12)] |

| 33. | Menda Y, O'Dorisio TM, Howe JR, Schultz M, Dillon JS, Dick D, Watkins GL, Ginader T, Bushnell DL, Sunderland JJ, Zamba GKD, Graham M, O'Dorisio MS. Localization of Unknown Primary Site with (68)Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT in Patients with Metastatic Neuroendocrine Tumor. J Nucl Med. 2017;58:1054-1057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed by the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer-reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single-blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: Croatia

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Wang ZJ, China S-Editor: Li L L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Cai YX