INTRODUCTION

The vermiform appendix is a slender, blind-ended diverticulum arising from the cecum, which has long been considered a redundant and nonfunctional organ. In 2021, the global age-standardized incidence rate of acute appendicitis was 214 per 100000, equating to approximately 17 million new cases[1]. The incidence rate was highest in the high-income Asia-Pacific area, at 364 per 100000, and lowest in western sub-Saharan Africa, at 81.4 per 100000. Acute appendicitis is among the most common causes of acute abdominal pain, and appendectomy remains the standard treatment[2]. This reinforces the prejudiced view that the appendix is a harmful and useless organ. However, in recent years, increasing evidence has confirmed that the appendix is an immune organ related to the immunity and stability of the colonic microbiota[3,4]. Given that the pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis (UC) involves dysregulated mucosal immunity and microbial dysbiosis, the relationship between the appendix and UC has garnered scientific interest. Studies have shown that appendectomy reduces the risk of developing UC and slows its progression[5]. However, other studies have shown that appendectomy increases the risk of colorectal resection, high-grade dysplasia, and colorectal cancer in UC[6,7]. With the successful development and promotion of endoscopic retrograde appendicitis therapy (ERAT) in recent years[8-10], treating appendicitis etiologically without appendectomy, thus preserving the function of the appendix, has become a reality. The aim of this review was to synthesize current evidence on the appendix-UC relationship and presents our novel methodological approach and clinical research findings.

NEW PERSPECTIVES ON THE PHYSIOLOGICAL ROLES OF THE APPENDIX

The appendix is a slender, blind-ended intestinal tube extending outward from the lower end of the cecum, measuring 5-7 cm in length and 0.5-1.0 cm in diameter. Congenital absence of the appendix is uncommon in humans. Its development starts around postnatal week 2, with gradual maturation followed by progressive atrophy typically beginning in early adulthood. Studies of comparative anatomy and microbial biofilms of the mammalian cecal appendix have shown that the phylogenetic development of the mammalian appendix has been conserved for thousands of years. The appendix and appendix-like structures are highly conserved in evolution, although they appear to have evolved independently multiple times[11]. Emerging evidence now identifies two primary physiological roles for the appendix, superseding historical views of vestigially.

Like the colonic wall, the appendiceal wall has a four-layer structure (mucosa, submucosa, muscularis propria, and serosa) but the appendiceal wall contains abundant lymphoid tissue. The appendix contains a high density of gut-associated lymphoid tissue, which develops in concert with the gut microbiota[12]. Immune cells in the appendix include a variety of innate immune cell populations, such as natural killer cells and intraepithelial CD8+ T cells. The appendix contains immune inductive sites, such as dense lymphoid follicles with B cells and germinal centers, and immune effector sites characterized by a lamina propria populated with plasma cells. Plasma cells that produce IgG and IgA are the main antibody-producing cells in appendiceal gut-associated lymphoid tissue and play a role in the response of B cells to microbial antigens[3,13,14].

The appendiceal lumen contains abundant microorganisms. Its tubular sealed structure, narrow lumen, and location at the base of the cecum collectively shield it from fecal flow and pathogenic microorganisms, while facilitating the accumulation of intraluminal biofilms[11]. Based on these characteristics, studies have speculated that the appendix is an ideal reservoir for beneficial biofilm bacteria[15]. When the body is infected by pathogenic bacteria or the gut microbiota is disrupted by antibiotics, the beneficial bacteria in the appendiceal lumen are released into the intestine to participate in the reconstruction of the gut microecological balance. In addition, the colon can be reinoculated with symbiotic bacteria regularly. Since the composition of the gut microbiome can vary over the short and long term, it is plausible that the appendiceal inoculum may be instrumental in maintaining the gut microbiome[12,15,16]. Therefore, the appendix is a unique reservoir for the microbiota. Multiple studies have shown that the appendix is an immune organ and ecosystem associated with mucosal immune function and stability of the colonic microbiome[3,16]. When other immune functions are weakened, the intestine is damaged, or the gut microbiota is disrupted, the appendix plays a significant role in immune regulation and gut microbiota regeneration[3]. Collard et al[17] analyzed data from 258 mammalian species and found that the presence of the cecal appendix is correlated with increased maximal observed longevity. This may be because the appendix promotes lifespan extension by reducing extrinsic mortality and the risk of fatal infectious diarrhea.

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE APPENDIX AND UC

From 1990 to 2019, the number of cases of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in males and females in China rose to 484000 and 427000, respectively, and it is projected that the IBD population in China will reach 1.5 million by 2025[18,19]. The Global Burden of Disease study 2021 reported that, over the past three decades, the incidence of IBD has surged in low- and middle-income countries, while its prevalence has stabilized in developed countries, with approximately 7 million people worldwide suffering from IBD[20]. The pathogenesis of IBD is not fully understood, but it is widely believed to be closely associated with genetic, environmental, microbiota, and immune-mediated factors[21-23]. Immune dysregulation and alterations in the gut microbiota are considered significant contributors to UC[24,25]. Fecal microbiota transplantation has been tried as a treatment for UC, and favorable effects have been reported[26,27]. Studies suggest that gut microbiota and mesenteric adipose tissue are potential therapeutic targets for Crohn’s disease[28]. The appendix can influence the regulation of the intestinal immune system and the stability of the intestinal microecology, and the relationship between the appendix and UC has consistently been a research focus in basic and clinical studies.

Appendectomy before the onset of UC can reduce the risk of future occurrence of UC and severity of the disease, and has a strong protective effect[29-31]. Epidemiological studies and meta-analyses have suggested a negative correlation between appendectomy and UC[15,29,32]. In the largest population-based cohort study to date, Frisch et al[32] conducted a follow-up study of 709353 appendectomy patients in Denmark and Sweden. They found that appendectomy reduced the incidence of UC, with a particularly significant decline observed in patients aged < 20 years. A national cohort study in Sweden that included > 100000 cases showed that juvenile appendicitis treated with appendectomy was associated with a decreased risk of adult IBD, including UC and Crohn’s disease[29]. Similarly, a meta-analysis incorporating research data from multiple countries across Europe and North America concluded that prior appendicectomy reduces the future risk of UC[5].

Owing to the potential protective effect of appendectomy on UC, it was once considered as a therapy for refractory UC. The prospective PASSION study by Sahami et al[33] included 30 patients with UC who underwent appendectomy after ineffective full medical therapy. After 12 months, nine patients had a lasting clinical response, of whom five were in endoscopic remission, and 13 patients had a reduced pathological inflammatory response. This suggests that appendectomy is effective in some patients with therapy-refractory UC patients. In April 2025, the results of a pragmatic, open-label, international, randomized trial published by the ACCURE study group showed that, from September 2012 to September 2022, among 22 medical centers, 197 patients with UC who met the study requirements (disease is in remission after treatment) were divided into a standard medical therapy alone group (98 cases) and a standard medical therapy plus appendectomy group (99 cases)[34]. After 1 year of follow-up, the relapse rate in the standard medical therapy alone group was 56%, while that in the standard medical therapy plus appendectomy group was 36%. This suggests that appendectomy is superior to standard medical therapy alone in maintaining remission in patients with UC[34]. However, these are only 1-year follow-up observation results (relapse rate, 56% vs 36%). The long-term efficacy of appendectomy in maintaining disease remission requires longer follow-up observation for validation.

Although appendectomy has the potential to alleviate the clinical manifestations of UC, some studies have reported that appendectomy may increase the risk of future colectomy, colorectal cancer, and high-grade dysplasia[6,35,36]. Shi et al[37] found that appendectomy promoted colorectal tumorigenesis through altering microbial composition and inducing intestinal barrier dysfunction in mice. Zhang et al[38] found that among Chinese UC patients who underwent appendectomy, the reasons for colectomy in 50% of patients were colorectal cancer or high-grade dysplasia, and 40.9% of the surgical indications were ineffective. Among UC patients who did not undergo appendectomy, the proportions were 9.4% and 86.3%, respectively. Sun et al[39] showed that appendectomy was associated with higher aggressiveness of subsequent ascending colon cancer, particularly regarding lymph node metastasis. A nationwide Danish population-based study concluded that appendectomy after UC was associated with a higher rate of colorectal resection, but patients with UC who underwent appendectomy did not experience a milder clinical course compared to those without appendectomy[40]. Whether UC patients can benefit from therapeutic appendectomy still requires high-quality medical evidence.

Regarding whether the effect of appendectomy in preventing the occurrence of UC is due to the surgery itself or to other potential pathological relationships, Frisch et al[32] simultaneously analyzed the influence of the reasons for appendectomy on the occurrence of UC in 709353 appendectomy patients. Appendicectomy for appendicitis or mesenteric lymphadenitis was associated with a significant risk reduction. In contrast, appendectomy without underlying inflammation was not associated with a reduced risk. Kiasat et al[29] found that juvenile appendicitis treated with appendectomy was associated with a decreased risk of adult UC. They also found that the risk of UC decreased in adult appendicitis patients after conservative therapy instead of appendectomy. The purpose of appendectomy or conservative therapy with antibiotics was to treat inflammation of the appendix, which indicated that inflammation of the appendix itself is related to the occurrence or progression of UC. Given the beneficial effects of the appendix, such as immune regulation and stabilization of the gut ecosystem, some studies have begun to question the necessity of surgical appendectomy. Particularly in children with uncomplicated appendicitis, conservative management with antibiotics is prioritized over appendectomy[41,42].

ERAT FOR THE DIAGNOSES AND TREATMENT OF UC WITH APPENDICEAL ORIFICE INFLAMMATION: A NEW DISCOVERY

UC accompanied by peri-appendicular red patches [PARPs, also known as appendiceal orifice inflammation (AOI) or cecal patches] is common in UC[3]. To determine whether there are inflammatory manifestations in the appendiceal lumen, Heuthorst et al[43] conducted a comparative study of 35 cases in each stage of remission and the active stage of UC, where all patients underwent appendectomy. They found that active appendiceal inflammation is common in UC, and > 50% of UC patients in remission showed active histological disease in the appendix. This study suggests that appendiceal inflammation is also a manifestation of UC, which provides a theoretical basis for adjuvant therapy of UC treating appendiceal inflammation[34].

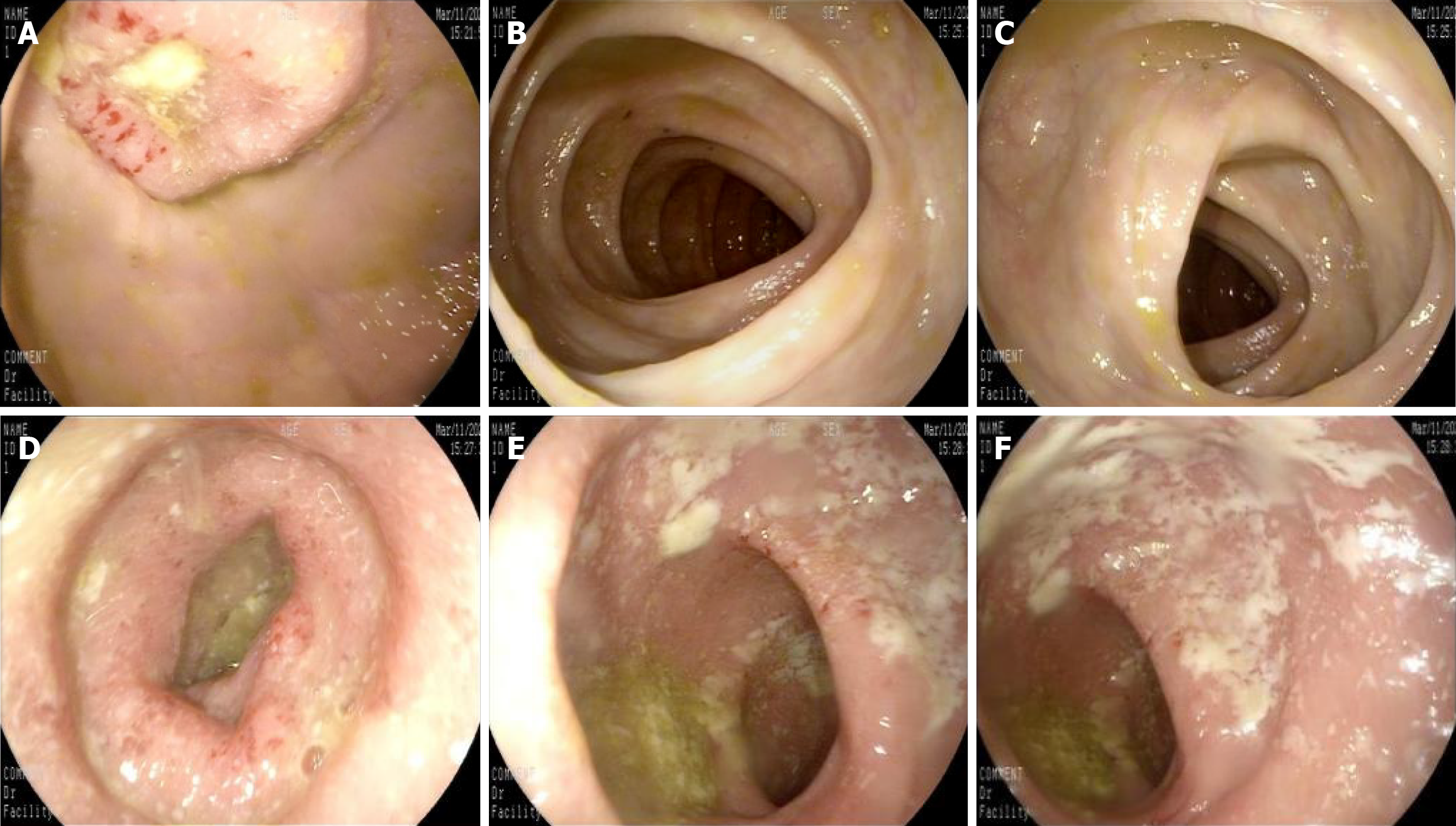

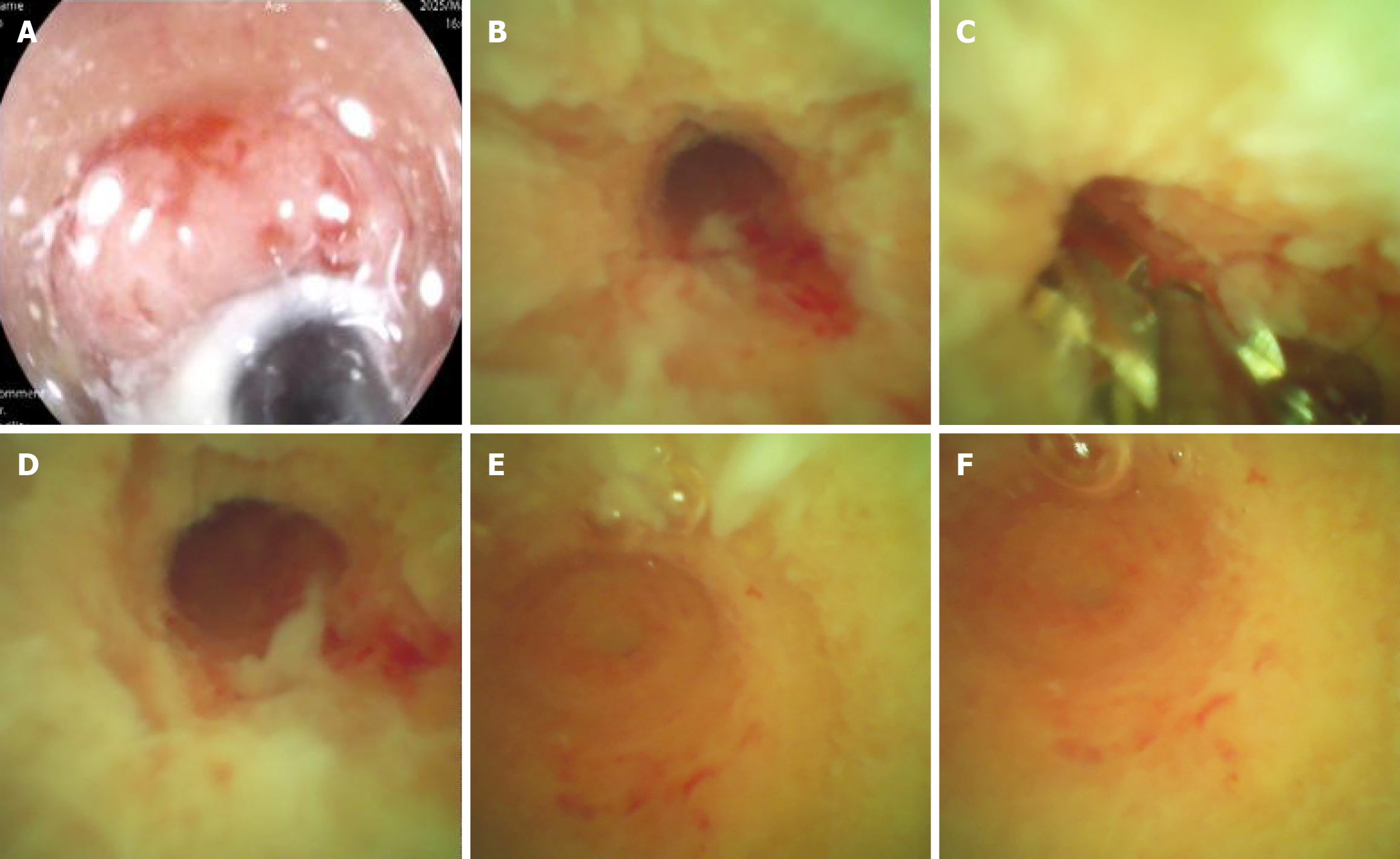

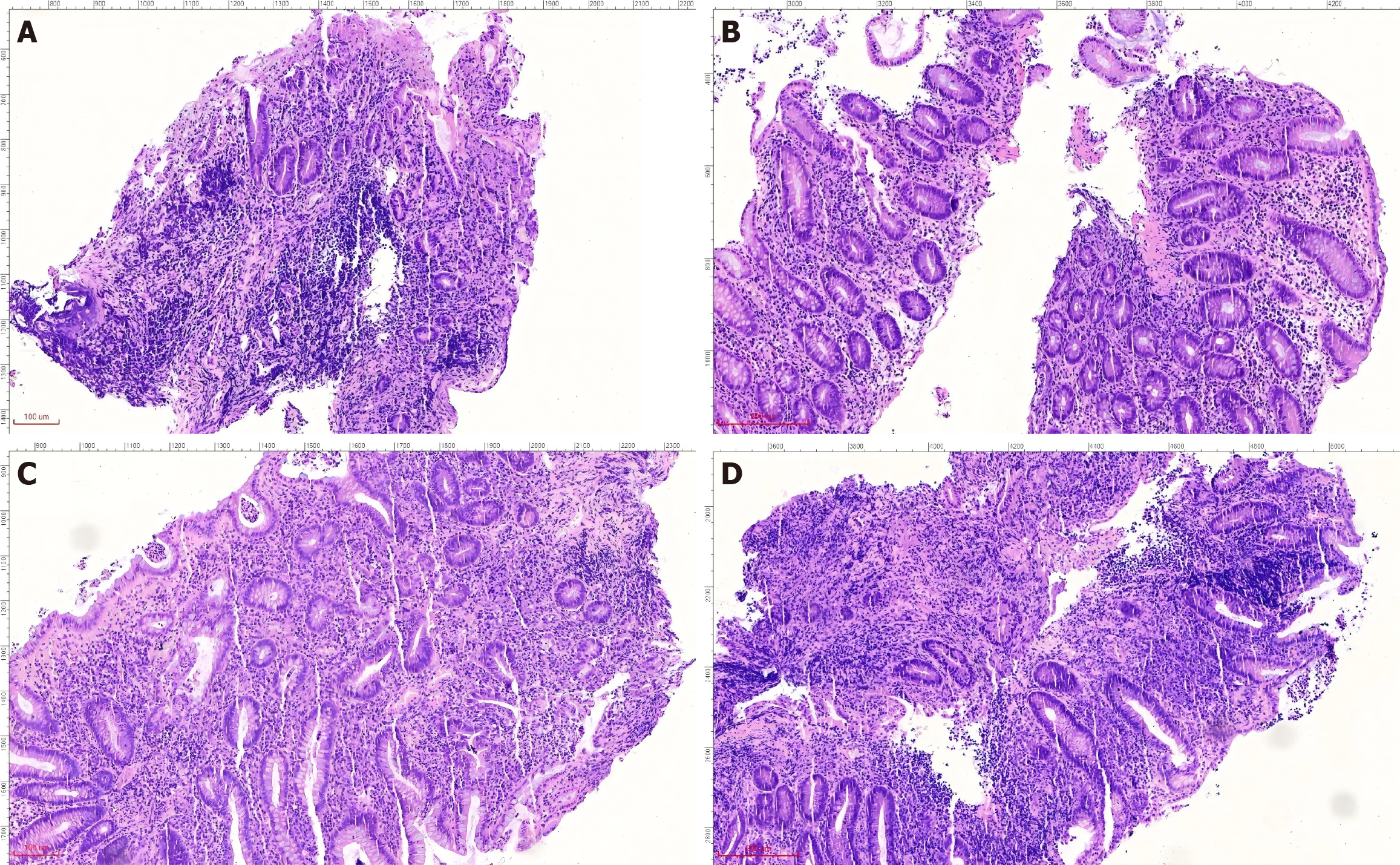

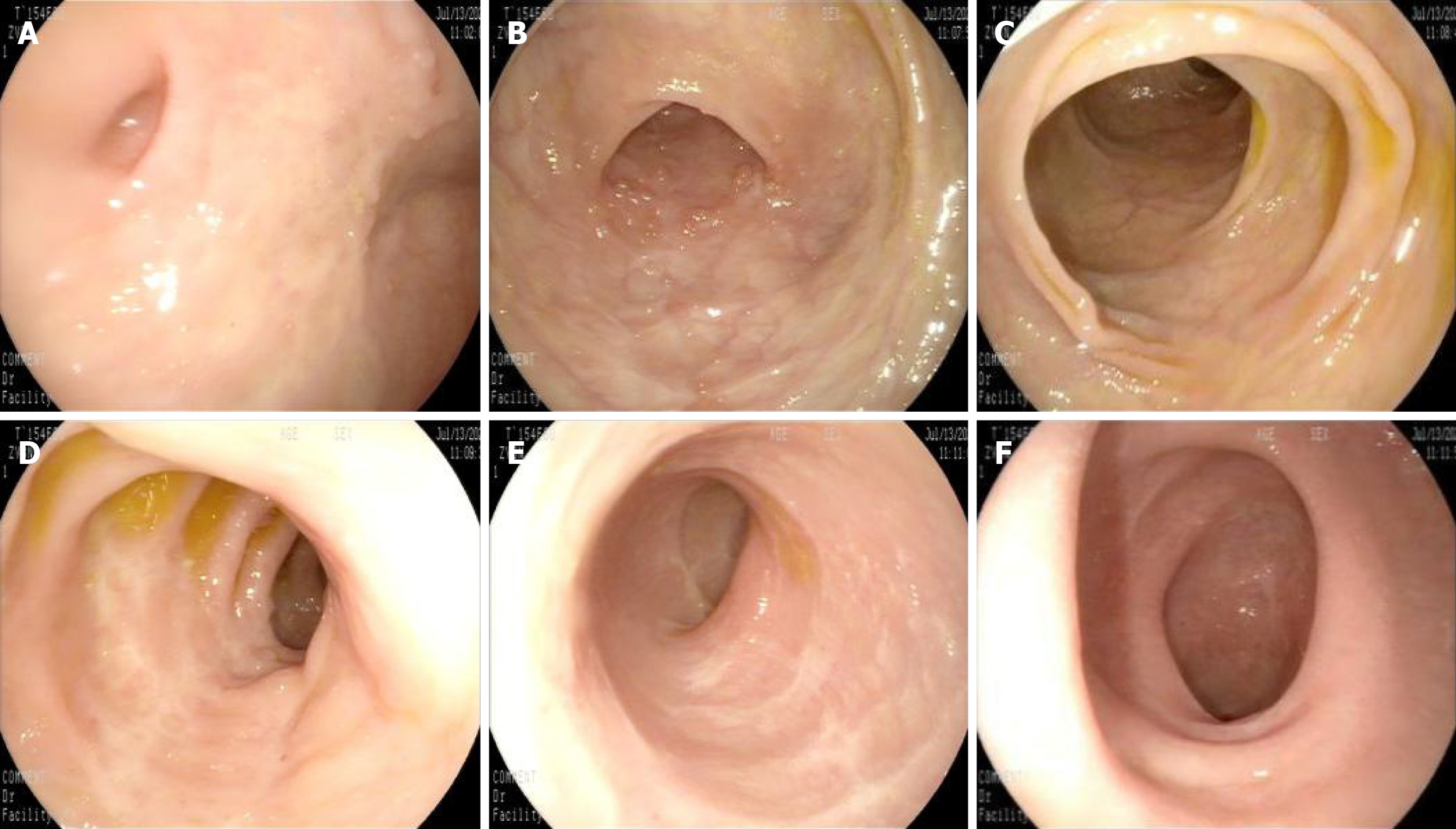

In recent years, the successful development and promotion of ERAT, particularly the mature application of a subscope allowing direct visualization in the diagnosis and treatment of appendiceal diseases, has made treating the root cause of appendiceal inflammation without removing the appendix a reality[8,44,45]. ERAT, which involves cannulation, appendicography, appendiceal stone extraction, appendiceal lumen irrigation, and stent insertion, has emerged as a promising noninvasive treatment modality for acute uncomplicated appendicitis. A comparative study of ERAT vs laparoscopic appendectomy for uncomplicated acute appendicitis showed that ERAT was a more technically feasible method of treating uncomplicated acute appendicitis compared with laparoscopic appendectomy[46]. It not only preserves the appendix and its functions but also avoids the potential future disease risks associated with appendectomy. Zulqarnain et al[47] were the first to report a successful case of using ERAT and placing a plastic stent under radiological intervention to treat UC complicated by chronic fecalith appendicitis. This approach resolved the patient’s appendiceal inflammation while preserving the appendix. Unfortunately, specific lesions inside the appendiceal lumen cannot be directly visualized. Our team used a subscope allowing direct visualization to enter the appendiceal lumen for observation and mucosal biopsy in two patients with recurrent UC accompanied by AOI and simultaneously performed ERAT[48]. In addition to the case documented in[48], a 48-year-old woman presented with a 2-year history of diarrhea, accompanied by worsening bloody stools over the past 6 months. Colonoscopy revealed a pyogenic legion with a mosslike appearance attached to the appendiceal orifice, accompanied by PARPs and erythematous and eroded mucosa in the rectum and sigmoid colon, while the descending, transverse, and ascending colon appeared endoscopically normal (Figure 1). The patient was diagnosed with UC (moderate activity, Mayo endoscopic score 3). When the subscope allowing direct visualization entered the appendiceal lumen, it was found that the vascular network of the appendiceal mucosa had disappeared, the mucosa was congested, edematous, and eroded, and there was a large amount of purulent secretion (Figure 2). The mucosa in the appendiceal lumen was similar to the colorectal mucosal lesions in UC, and an appendiceal mucosal biopsy was performed (Figure 2C). The appendiceal lumen was thoroughly irrigated with metronidazole solution. After removing the inflammatory secretions from the lumen, the patient’s symptoms, such as abdominal pain, improved rapidly. A new discovery was that the pathological findings of appendiceal, ileocecal, sigmoid, and rectal mucosal biopsies were consistent with ulcerative changes: Uneven distribution of crypts, crypt distortion, visible cryptitis, massive plasma cell and lymphocyte infiltrations in the stroma, and focal neutrophil infiltrations (Figure 3). Standard medical therapy (oral mesalamine 1 g, three times a day) was continued after ERAT. Six months later, follow-up colonoscopy showed that the appendiceal orifice and surrounding mucosa were normal, and the ulcerative colorectal mucosa had healed (remission, Mayo endoscopic score 0; Figure 4).

Figure 1 Endoscopic findings throughout the colon: Pyogenic lesion at appendiceal orifice and distal inflammation.

A: Appendiceal orifice. Pyogenic legion with a mosslike appearance attached to the appendiceal orifice, and the lesion was accompanied by peri-appendicular red patches; B: Ascending colon, mucosa appeared normal; C: Transverse colon, mucosa appeared normal; D: Descending colon, mucosa appeared normal; E: Sigmoid colon, erythematous and erosion with attached inflammatory secretions endoscopically; F: Rectum, erythematous and erosion with attached inflammatory secretions endoscopically.

Figure 2 Endoscopic appearance of suppurative appendicitis: Characteristic inflammatory changes from orifice to blind end.

A: Appendiceal orifice; B: Proximal appendiceal lumen; C: Mucosal biopsy; D: Middle part of appendiceal lumen; E and F: Blind end of appendix. Appendiceal mucosa showing diffuse edema, hyperemia, erosion, and a large number of purulent secretions.

Figure 3 Histopathological diagnosis of ulcerative colitis across multiple colonic sites.

A: Appendix; B: Ileocecal region; C: Sigmoid colon; D: Rectum. The pathological findings of appendiceal, ileocecal, sigmoid, and rectal mucosal biopsies were consistent with ulcerative changes: Uneven distribution of crypts, crypt distortion, visible cryptitis, focal crypt loss, massive plasma cell and lymphocyte infiltration in the stroma, and focal neutrophil infiltration.

Figure 4 Endoscopic contrast: Normal proximal colon vs healed ulcer scars in the distal colon.

A: Appendiceal orifice, normal appendiceal orifice and surrounding mucosa; B: Ascending colon, mucosa appeared normal; C: Transverse colon, mucosa appeared normal; D: Descending colon, mucosa appeared normal; E: The sigmoid colon mucosa showed ulcer scars, indicating healing; F: The rectal mucosa similarly exhibited ulcer scars, consistent with mucosal healing.

ERAT under a subscope allowing direct visualization has advantages such as rapid efficacy, ultraminimal invasiveness, few complications, and a low relapse rate[9,44,49]. This technique provides technical support for the treatment of appendicitis while completely preserving the appendix. Using the subscope for examination and therapy of two patients with UC complicated by AOI, we found the following: (1) Under the subscope, mucosal manifestations in the appendiceal lumen were similar to those of the colorectal mucosa, and the pathological changes were also consistent with patients with UC; and (2) Based on the standard medical therapy for UC, performing ERAT on the appendix can improve the therapeutic effect, offering a potential addition to standard medical therapies. To determine whether these novel findings apply universally, further research with an enlarged sample size is required.

CONCLUSION

The role of the appendix in human immune regulation and intestinal microecological homeostasis is increasingly recognized, displacing the outdated notion that it as a vestigial organ. The physiological functions of the appendix are closely related to the pathogenesis of UC. Evidence confirms an inverse correlation between appendectomy and UC incidence. This has led to intense research focusing on appendectomy for the therapy of UC. However, there is still considerable controversy over whether patients with UC can benefit from therapeutic appendectomy. This is primarily because the future risks after appendectomy and the development of IBD are associated with multiple factors[7,21,50].

ERAT represents a novel approach that preserves appendiceal integrity while treating appendicitis, thereby maintaining its immune functions and stabilizing the intestinal microecology. This technique offers a platform for deeper exploration of appendiceal pathophysiology and UC treatment strategies. Our team used direct choledochoscopic visualization to examine, diagnose, and treat two cases of UC with AOI. We found ulcerative appendicitis within the appendiceal lumen, exhibiting histopathological features analogous to UC. Concurrently, appendiceal lavage enhanced UC treatment efficacy. These findings raise a critical question: Could this approach offer new therapeutic potential for the UC subtype characterized by AOI or PARPs? Next, a clinical controlled trial with an increased sample size should be conducted. Our integrated clinical, endoscopic, and pathological observations support a plausible association between the appendix and UC pathogenesis, suggesting the appendix may serve as a priming site for UC. We will continue appendiceal-targeted therapy for the UC with AOI subtype, aiming to provide clinical evidence to clarify the relationship between the appendix and UC.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B, Grade B, Grade B

Novelty: Grade B, Grade B, Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B, Grade B, Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade B, Grade B, Grade B

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P-Reviewer: de Bastos DRR, Researcher, Paraguay; Tiwari A, MD, India S-Editor: Zuo Q L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xu J