Published online Feb 16, 2026. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v18.i2.113393

Revised: October 11, 2025

Accepted: December 17, 2025

Published online: February 16, 2026

Processing time: 164 Days and 11.8 Hours

Precise characterization of pancreatic head lesions remain a challenge even with all the radiological advancement. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is the most common malignant lesion, but many other malignant and benign pathology can masque

To see the role of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) in characterizing solid pancreatic head lesions.

This is a retrospective analysis of prospectively maintained databases in a tertiary care centre of north India. Patients with suspicious solid mass lesion in pancreatic head in computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging who underwent EUS-guided fine needle biopsy in last 3 (2020-2022) years were analyzed. Those who have at least 6 months of follow up or follow up until surgery or death were included. Different EUS characteristics were compared to look for predictors of malignant head lesions.

Total 92 patients enrolled, among which 53 patients excluded and 39 included in final analysis. Twenty-four (61.5%) patients had pancreatic adenocarcinoma, 1 (2.6%) neuro-endocrine cancer, 11 (28.2%) inflammatory head mass, 2 (5.1%) auto immune pancreatitis and 1 had pancreatic tuberculosis. History of acute pancreatitis in recent past significantly favoured benign pathology. Increased pancreatic duct diameter (5.2 ± 2.5 mm vs 3.3 ± 1 mm; P = 0.01) and negative duct penetrating sign [22 (88%) vs 7 (50%); P = 0.03] predicted malignancy. In EUS-elastography both qualitative (colour pattern) (P = 0.01) and quantitative (strain ratio) (P = 0.02) parameters found to be signi

This study showed some promising preliminary results of EUS and EUS elastography in differentiation of solid pancreatic head lesion. But it requires validation in larger and prospective study.

Core Tip: A precise diagnosis of a pancreatic head lesions is fundamental to effective management and a favorable final outcome. This retrospective study underscores the critical role of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) in these cases. Apart from EUS-guided biopsy, EUS characteristics like pancreatic duct diameter, pancreatic duct course and EUS elastographic parameters like color pattern, strain ratio also provide important clue to differentiate benign and malignant pancreatic head lesions.

- Citation: Sahu P, Mazumdar S, Kumar JS, Garg A, Singh S, Rejliwal P, Kar P. Endoscopic ultrasound in differentiation of solid pancreatic head lesions: A single centre experience. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2026; 18(2): 113393

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v18/i2/113393.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v18.i2.113393

Accurate diagnosis of solid pancreatic head mass remains a challenge, despite recent advances in several diagnostic procedures. A solid pancreatic head lesion is highly concerning for malignancy, particularly if accompanied by jaundice and unexplained weight loss. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma is the most common malignant lesion of the pancreas (85%-95%) and it has extremely poor prognosis, with 5-year survival of only 8%-9%[1,2]. But many other non-malignant (like inflammatory head mass, mass forming chronic pancreatitis, autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP), tuberculosis, lipoma) and malignant (like neuroendocrine tumors, metastasis, lymphoma, sarcoma) lesions may present as similar mass lesions in pancreatic head[3]. Confirming the diagnosis is pivotal because uncertainty may lead to either major pancreatic resection for benign disease or rejection of surgery for a potentially curable lesion. Unfortunately, due to overlap of cli

The emergence of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) in recent years have revolutionized the management of pancreatic head lesions. High frequency EUS probes in stomach and duodenum can provide detailed images with no intervening bowel gases[7]. New EUS based technology like EUS elastography or contrast enhanced- EUS helps in better characterization of pancreatic mass lesion. More over with EUS-fine needle aspiration cytology or fine needle biopsy (FNB), tissue acquisition of suspicious pancreatic mass lesion is possible[7]. In this retrospective study we will analyse the EUS characteristics and its role in making correct diagnosis of suspicious solid pancreatic head lesions.

We performed a retrospective analysis of prospectively maintained databases in a tertiary care centre of north India. Patients with suspicious solid mass lesion in pancreatic head in CT-scan/MRI who underwent EUS-FNB in last 3 (2020-2022) years were analyzed. Those patients who have at least 6 months of follow up (F/U) or F/U until surgery or death were included in the study.

Final diagnosis of malignant or benign lesion was defined according to the Cytology and histology report of EUS-FNB specimen and histology of surgical specimens in cases undergoing surgery: (1) A definitely positive cytology/histology for malignancy together with compatible EUS and radiological findings confirm the final diagnosis of malignant lesions in unresectable cases, as histology of surgical specimen in patients who underwent surgery; and (2) EUS-FNB report along with other EUS characteristics, compatible radiological findings, minimum follow-up period of 6 months to look for clinical course and response to treatment confirm benign lesions.

All EUS were performed by expert endosonologist with linear array echoendoscope (Olympus CV-190; EU-ME2 premiere plus processor, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Features of pancreatic mass at EUS evaluation (like size, location, echogenicity, ‘duct penetrating sign’, calcification, surrounding lymphadenopathy, surrounding vascular involvement and elasto

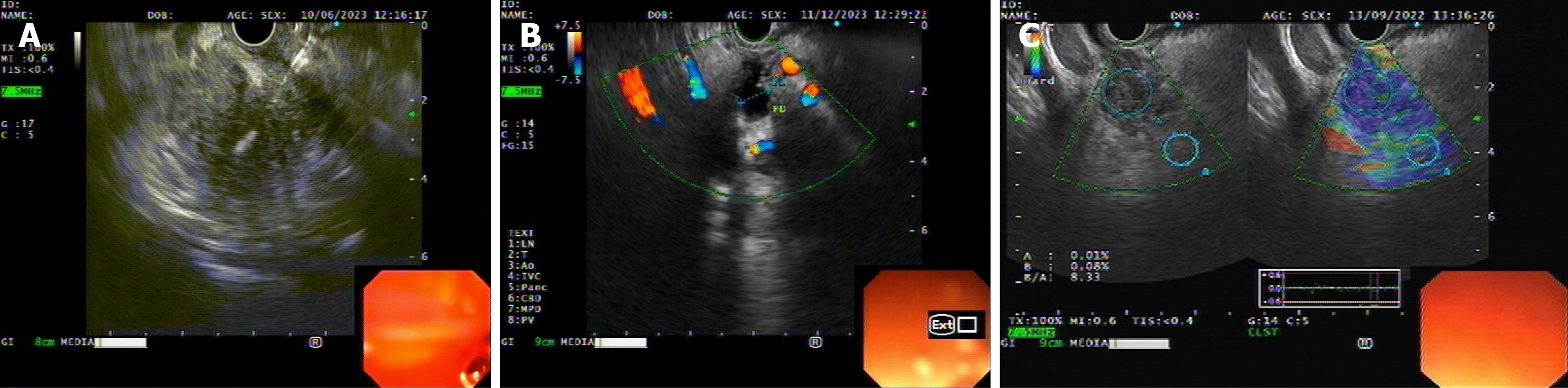

For elastography, probe was approximated to the wall with adequate pressure needed for optimal quality and stable B-mode image at 7.5 MHz frequency. The region of interest (ROI) was adjusted manually to include the whole target lesion when possible (lesion covers 20%-50% ROI) as well as surrounding tissues. When elastographic image shows stable pattern for 5 seconds then it was fixed for quantitative analysis and final pattern definition. Two different areas (A and B) from the ROI were selected. Area A represents area of the mass and area B represents a peripancreatic or pancreatic reference area outside the lesion. Strain ratio (B/A) was calculated for the semiquantitative measurement of the elasto

Once EUS elastography was done, EUS-FNB of the pancreatic mass was performed with a 22-gauge or 25-gauge needle (“Acquire” EUS-FNB needle from Boston scientific) (Figure 1C). Sampling techniques like “fanning”, “slow pull” were used in all cases and rarely “wet suction” was used. Rapid on-site evaluation was not available. Samples wire submitted in slides (dry and alcohol fixed) and cell blocks for all the cases. In cases with high suspicion of malignancy in EUS and other investigations, if initial histology report came negative for malignancy, repeat EUS- FNB done.

Baseline data were recorded as n (%), mean ± SD or median (inter quartile range) as suitable. χ2 test was used for categorical variables, Student’s t-test was used for continuous variables with normal distribution and Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables without a normal distribution. P value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 21.0, Chicago, IL, United States).

Total 92 patients identified who underwent EUS-FNB for solid pancreatic head lesion in last 3 years. Fifty-three patients excluded due to loss of follow up, unavailability of relevant investigations or biopsy reports. Thirty-nine patients, who have at least 6 months of F/U or F/U until surgery or death, were included in the study.

Total 25 (64.1%) patients had malignant head lesion, 24 (61.5%) patients had pancreatic adenocarcinoma and 1 patient had neuro-endocrine cancer. Eleven (28.2%) patients had inflammatory head mass (Table 1). Two patients (5.1%) had AIP, diagnosed, based on histopathology and raised IgG4 level. Both of them responded to steroid. One patient had necrotizing epithelioid granuloma in histopathology and responded to anti-tubercular drug. Among these 39 patients, 2 patients had repeat EUS-FNB as initial biopsy did not show malignancy but there was high suspicion of malignancy on follow up and other evaluation. One turned out adeno-carcinoma on repeat biopsy and the other found to be inflammatory head mass.

| Diagnosis | n (%) |

| Malignant | 25 (64.1) |

| Adeno-carcinoma | 24 (61.5) |

| Neuro-endocrine cancer | 1 (2.6) |

| Inflammatory | 11 (28.2) |

| Auto-immune pancreatitis | 2 (5.1) |

| Tuberculosis | 1 (2.6) |

Majority of patients were of advanced age (mean age 61.1 ± 8.9 years) and male patients (male:female 64:36). There was no significant difference in age and sex distribution, or history of smoking and alcohol between patients with malignant head mass or benign head lesions (Table 2). Eight (20.5%) patients had underlying chronic pancreatitis, 6 found to have adenocarcinoma and 2 had inflammatory head mass (P = 0.69). None of the patients with malignant head lesion had history of acute pancreatitis and 4 (28.6%) patients with inflammatory head lesion had history of acute pancreatitis in recent past (P = 0.012). Serum CA-19-9 was not significantly different between benign and malignant head lesions [156 (16-490) U/mL vs 192 (126-417) U/mL; P = 0.46] (Table 2).

| Characteristic | Malignant lesion (n = 25) | Benign lesion (n = 14) | P value |

| Age (years) | 60 ± 8.7 | 63.2 ± 9.3 | 0.28 |

| Sex (male: Female) | 64:36 | 64:36 | 0.98 |

| Alcoholics | 8 (32) | 7 (50) | 0.27 |

| Smoking | 11 (44) | 4 (28.6) | 0.49 |

| Significant weight loss | 17 (68) | 6 (42.9) | 0.13 |

| History of acute pancreatitis | 0 | 4 (28.6) | 0.012 |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 6 (24) | 2 (14.3) | 0.69 |

| Bilirubin | 4.8 (1.4-6.3) | 1.8 (0.4-3.2) | 0.17 |

| SGOT | 54 (34-76) | 45 (30-209) | 0.77 |

| SGPT | 38 (34-78) | 38 (32-331) | 0.77 |

| ALP | 410 (198-506) | 396 (110-591) | 0.94 |

| CA-19-9 | 192 (126-417) | 156 (16-490) | 0.46 |

All the EUS characteristics (size of the lesions, Dilated common bile duct, dilated PD, double duct sign, vascular involvement, surrounding lymphadenopathy, echogenicity, elastography characteristics) were compared between the malignant and benign head lesions (Table 3). PD diameter was significantly more in malignant group compared to benign head lesion (5.2 ± 2.5 mm vs 3.3 ± 1 mm; P = 0.01). Duct penetration sign was seen only in 3 (12%) patients with adenocarcinoma and 7 (50%) patients with benign head lesions (P = 0.03). Elastography characteristics found to be significant predictor of malignant lesion [predominantly blue in 20 (80%) malignant lesion vs 3 (21.4%) benign lesions; P = 0.01]. Strain ratio was not available for all the patients. Nineteen among 39 patients had strain ratio available due to technical limitation. Strain ratio was significantly higher in malignant lesions (26 ± 7.2 vs 14.8 ± 10.2; P = 0.02) (Table 3).

| Characteristic | Malignant lesion (n = 25) | Benign lesion (n = 14) | P value |

| Dilated CBD | 19 (76) | 9 (64.3) | 0.43 |

| Dilated PD | 19 (76) | 8 (57.1) | 0.22 |

| Double duct sign | 14 (56) | 6 (42.9) | 0.43 |

| CBD diameter (mm) | 12.8 ± 4.8 | 10.9 ± 3.5 | 0.19 |

| PD diameter (mm) | 5.2 ± 2.5 | 3.3 ± 1 | 0.01 |

| Max diameter of lesion (mm) | 32.2 ± 12 | 31.4 ± 3.2 | 0.75 |

| Duct penetration | 3 (12) | 7 (50) | 0.03 |

| Surrounding vascular encasement | 5 (20) | 0 | 0.14 |

| Significant peripancreatic LAP | 9 (36) | 1 (7.1) | 0.1 |

| Calcification with in the lesion | 2 (8) | 2 (14.3) | 0.6 |

| Echogenicity | Hypoechoic - 16 (64) | Hypoechoic - 5 (35.7) | 0.09 |

| Heteroechoic - 9 (36) | Heteroechoic - 9 (64.3) | ||

| Elastography | Heterogenous; predominantly blue - 20 (80) | Heterogenous; predominantly blue- 3 (21.4) | 0.01 |

| Heterogenous; predominantly green - 5 (20) | Heterogenous; predominantly green - 11 (78.6) | ||

| Strain ratio | 26 ± 7.2 (n = 13) | 14.8 ± 10.2 (n = 6) | 0.02 |

This retrospective study highlights the importance of EUS-FNB in making correct diagnosis in patients with suspicious pancreatic head lesions. Even after evaluating clinical characteristics, biochemical parameters, CT or MRI imaging, a group of such patients will require EUS and biopsy to precisely diagnose the nature of the lesion. In this study, 64.1% cases were found to be malignant, rest 35.9% were benign. Two such cases were auto-immune pancreatitis and 1 case was tuberculosis, required specific treatment and had complete response. We have included only solid head lesions and excluded lesion in other parts of pancreas and cystic lesion of pancreas, to reduce the heterogenicity and as different protocol followed for cystic lesions. EUS-guided tissue acquisition now considered the gold standard to diagnose pancreatic lesions. EUS have shown high sensitivity (92%-100%), specificity (89%-100%) in detection of pancreatic malignancies[7-9]. As EUS-FNB has been replaced EUS-FNA in view of greater diagnostic accuracy (odds ratio = 1.62, 95% confidence interval: 1.17-2.26) and tissue adequacy (odds ratio = 1.83, 95% confidence interval: 1.27-2.64) which also helps in molecular profiling, in our centre we usually do EUS-FNB in all such cases[10,11]. It also avoids the need for rapid onsite evaluation, as we don’t have that facility in our set-up.

Among clinical and biochemical parameters, only history of acute pancreatitis found to be a predictor of benign head lesion. Though, CA-19-9 is the long-established biomarker of pancreato-biliary malignancy, it was not found significant. Ballehaninna and Chamberlain[12] also highlighted the limitation CA-19-9 in pancreatic head lesions with false negative result in Lewis negative cases (5%-10%) and false positive results in cases with biliary obstruction (10%-60%).

Canto et al[13] and Tacelli et al[14] have described several EUS characteristics supportive of malignant lesion like, size above 2 cm, irregular dilation of the main PD, low vascularity of mass, absence of cysts within the mass, presence of large peripancreatic lymph nodes and vascular invasion. Most of these studies were done in patients with chronic pancreatitis to differentiate between inflammatory and malignant mass. Only 8 (20.5%) patients in our study had underlying chronic pancreatitis. We have analysed all the EUS characteristics in our study group. Only negative duct penetration sign and PD diameter found to be significant predictor of malignant lesions. Duct penetration sign (positive, when unobstructed PD can be traced through the mass) is also useful radiologically to differentiate benign or malignant pancreatic lesion in CT or MRI. Earlier studies have shown its utility in EUS[14,15]. Few other parameters like vascular encasement, echogenicity of the lesion although showed differential pattern between malignant and benign lesion but did not achieve statistical significance, likely because of small sample size.

This study highlighted the utility of EUS-elastography in evaluation and characterization of solid pancreatic head mass. Both qualitative (colour pattern) and quantitative (strain ratio) elastography index were found significant in predicting malignant lesions. In the metanalysis by Li et al[16], EUS elastographic colour pattern showed a sensitivity of 99% (0.97-1) and specificity of 76% (0.67-0.83) and hue-histogram showed 92% sensitivity in differentiating malignant from inflammatory pancreatic head mass. Recently multiple studies showed diagnostic value of EUS- elastography strain ratio in diagnosing malignant pancreatic lesion[17,18]. Iglesias-Garcia et al[18] reported strain ratio > 10 or strain histogram level < 50 identified pancreatic malignant lesions with 100% sensitivity and 92.3% specificity. Receiver operating curve was not drawn in our study to derive cut-off value as sample size was less (strain ratio available only for 19 patients due to technical limitations).

In most of our cases we had multidisciplinary team discussion among gastroenterologists, radiologists, gastrointestinal surgeons, pathologists regarding clinical presentations, CT or MRI findings, and EUS characteristics. These multidisciplinary team discussion also played a valuable role in accurate characterization of the lesion. Maurea et al[19] also descri

Most of the similar studies in past mainly included patients with underlying chronic pancreatitis, but this study had more varied patient population with varied nature of lesions depicting real life clinical scenario. It highlighted im

But there are some limitations like small sample size, non-uniform follow-up, as it is a single centre retrospective analysis. Significant number of patients were excluded from the final study as they lost to follow up. Multivariable analysis was also not performed because of low sample size. Contrast-enhanced EUS were not done for these patients in our centre (mostly because of financial reason).

Amidst some limitations, this study showed some promising preliminary results of EUS and EUS elastography in differentiation of solid pancreatic head lesion. It requires further validation in larger and prospective study.

| 1. | Connor AA, Gallinger S. Pancreatic cancer evolution and heterogeneity: integrating omics and clinical data. Nat Rev Cancer. 2022;22:131-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 57.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Coleman MP, Forman D, Bryant H, Butler J, Rachet B, Maringe C, Nur U, Tracey E, Coory M, Hatcher J, McGahan CE, Turner D, Marrett L, Gjerstorff ML, Johannesen TB, Adolfsson J, Lambe M, Lawrence G, Meechan D, Morris EJ, Middleton R, Steward J, Richards MA; ICBP Module 1 Working Group. Cancer survival in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and the UK, 1995-2007 (the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership): an analysis of population-based cancer registry data. Lancet. 2011;377:127-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 880] [Cited by in RCA: 897] [Article Influence: 59.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Masuda S, Koizumi K, Shionoya K, Jinushi R, Makazu M, Nishino T, Kimura K, Sumida C, Kubota J, Ichita C, Sasaki A, Kobayashi M, Kako M, Haruki U. Comprehensive review on endoscopic ultrasound-guided tissue acquisition techniques for solid pancreatic tumor. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:1863-1874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Eapen A, Chandramohan A, John R, Simon B, Putta T, Joseph AJ. Imaging of an Indeterminate Pancreatic Mass. J Gastrointest Abdom Radiol. 2020;3:75-86. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kitano M, Yoshida T, Itonaga M, Tamura T, Hatamaru K, Yamashita Y. Impact of endoscopic ultrasonography on diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2019;54:19-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 33.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | van Heerde MJ, Biermann K, Zondervan PE, Kazemier G, van Eijck CH, Pek C, Kuipers EJ, van Buuren HR. Prevalence of autoimmune pancreatitis and other benign disorders in pancreatoduodenectomy for presumed malignancy of the pancreatic head. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:2458-2465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dutta AK, Chacko A. Head mass in chronic pancreatitis: Inflammatory or malignant. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7:258-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mohan BP, Madhu D, Reddy N, Chara BS, Khan SR, Garg G, Kassab LL, Muthusamy AK, Singh A, Chandan S, Facciorusso A, Mangiavillano B, Repici A, Adler DG. Diagnostic accuracy of EUS-guided fine-needle biopsy sampling by macroscopic on-site evaluation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;96:909-917.e11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Banafea O, Mghanga FP, Zhao J, Zhao R, Zhu L. Endoscopic ultrasonography with fine-needle aspiration for histological diagnosis of solid pancreatic masses: a meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy studies. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;16:108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bang JY, Hebert-Magee S, Navaneethan U, Hasan MK, Hawes R, Varadarajulu S. EUS-guided fine needle biopsy of pancreatic masses can yield true histology. Gut. 2018;67:2081-2084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Li H, Li W, Zhou QY, Fan B. Fine needle biopsy is superior to fine needle aspiration in endoscopic ultrasound guided sampling of pancreatic masses: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e0207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ballehaninna UK, Chamberlain RS. The clinical utility of serum CA 19-9 in the diagnosis, prognosis and management of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: An evidence based appraisal. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2012;3:105-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 372] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 13. | Canto MI, Hruban RH, Fishman EK, Kamel IR, Schulick R, Zhang Z, Topazian M, Takahashi N, Fletcher J, Petersen G, Klein AP, Axilbund J, Griffin C, Syngal S, Saltzman JR, Mortele KJ, Lee J, Tamm E, Vikram R, Bhosale P, Margolis D, Farrell J, Goggins M; American Cancer of the Pancreas Screening (CAPS) Consortium. Frequent detection of pancreatic lesions in asymptomatic high-risk individuals. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:796-804; quiz e14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 451] [Cited by in RCA: 504] [Article Influence: 36.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tacelli M, Zaccari P, Petrone MC, Della Torre E, Lanzillotta M, Falconi M, Doglioni C, Capurso G, Arcidiacono PG. Differential EUS findings in focal type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer: A proof-of-concept study. Endosc Ultrasound. 2022;11:216-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sreenarasimhaiah J. Efficacy of endoscopic ultrasound in characterizing mass lesions in chronic pancreatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:81-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Li X, Xu W, Shi J, Lin Y, Zeng X. Endoscopic ultrasound elastography for differentiating between pancreatic adenocarcinoma and inflammatory masses: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:6284-6291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Iglesias-Garcia J, Larino-Noia J, Abdulkader I, Forteza J, Dominguez-Munoz JE. Quantitative endoscopic ultrasound elastography: an accurate method for the differentiation of solid pancreatic masses. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1172-1180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Iglesias-Garcia J, Lindkvist B, Lariño-Noia J, Abdulkader-Nallib I, Dominguez-Muñoz JE. Differential diagnosis of solid pancreatic masses: contrast-enhanced harmonic (CEH-EUS), quantitative-elastography (QE-EUS), or both? United European Gastroenterol J. 2017;5:236-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/