Published online Jan 16, 2026. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v18.i1.114791

Revised: October 11, 2025

Accepted: November 21, 2025

Published online: January 16, 2026

Processing time: 109 Days and 8.9 Hours

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) represents the standard surgical approach for resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC); however, its high morbidity has prompted the exploration of minimally invasive alternatives. While laparoscopic PD (LPD) has demonstrated promise, evidence comparing LPD and open PD (OPD) in early-stage PDAC remains limited.

To compare the perioperative and oncologic outcomes of LPD and OPD in pat

This retrospective propensity-matched analysis included 100 patients with stage I-II PDAC who underwent cu

Compared with OPD, LPD was associated with reduced intraoperative blood loss [median 170 mL (interquartile range: 130-220 mL) vs median 340 mL (interquartile range: 280-410 mL); P < 0.001], lower transfusion rates (8% vs 22%; P = 0.03), and shorter hospital stays (12 ± 3 days vs 15 ± 4 days; P = 0.002), although operative times were longer (320 ± 45 minutes vs 285 ± 40 minutes; P < 0.001). Overall complication rates (42% vs 50%), severe complications (16% vs 22%), pancreatic fistula (12% vs 16%), delayed gastric emptying (10% vs 14%), and specific complications (wound infection: 6% vs 14%; intra-abdominal abscess: 4% vs 6%; bile leak: 2% vs 4%; pulmonary complications: 8% vs 12%; sepsis: 4% vs 6%) were comparable between the groups (all P > 0.05). enhanced recovery after surgery metrics favored LPD, with earlier mobilization (8.5 ± 3.2 hours vs 12.4 ± 4.1 hours; P = 0.001), earlier oral intake (1.2 ± 0.5 days vs 2.1 ± 0.8 days; P < 0.001), and lower pain scores (3.5 ± 1.2 vs 4.8 ± 1.5; P < 0.001). Oncologic outcomes, including lymph node yield, R0 resection rates, recurrence-free survival, and OS, were similar, with a median OS of 22 months for LPD vs 20 months for OPD (log-rank P = 0.65).

LPD offers perioperative benefits, including reduced blood loss, fewer transfusions, shorter hospital stays, and improved recovery metrics, without compromising oncologic outcomes in early-stage PDAC. These findings support its selective use in high-volume centers with experienced surgeons, promoting faster recovery while maintaining long-term efficacy.

Core Tip: Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) remains the cornerstone treatment for resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, but its morbidity is substantial. Minimally invasive techniques, particularly laparoscopic PD (LPD), have emerged as alternatives to open surgery. However, evidence in early-stage pancreatic cancer is limited. In this propensity-matched analysis from a high-volume center, LPD demonstrated reduced blood loss (by 170 mL), fewer transfusions, and a shorter hospital stay (by 3 days), while showing comparable complication rates, R0 resection rates, lymph node yield, and survival outcomes to open PD. These findings suggest that LPD may be a safe and effective option in carefully selected early-stage patients, supporting its integration into surgical practice in experienced centers.

- Citation: Kalim M, Sarwar M, Chishti SSA, Ali M, Qayyum S, Ahmed J, Memon M, Shenawa E. Comparative outcomes of laparoscopic vs open pancreaticoduodenectomy in early-stage pancreatic cancer. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2026; 18(1): 114791

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v18/i1/114791.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v18.i1.114791

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) accounts for approximately 90% of pancreatic malignancies and poses a significant global health challenge[1]. Despite advancements in multimodal therapies, the 5-year overall survival (OS) rate for PDAC remains a dismal 13%, primarily due to late diagnosis and the disease’s aggressive nature[2,3]. For early-stage disease (stages I-II), pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD), commonly known as the Whipple procedure, represents the primary treatment, offering a median survival of 20-30 months when combined with adjuvant chemotherapy[4]. However, PD is a complex operation associated with substantial morbidity (up to 50%) and mortality (2%-5%)[5,6].

Laparoscopic PD (LPD) has emerged as a promising minimally invasive alternative to traditional open PD (OPD). Advocates of LPD highlight its potential for reduced intraoperative blood loss, shorter hospital stays, and faster recovery, attributed to enhanced visualization, precise instrumentation, and minimized tissue trauma[7]. Nevertheless, concerns persist regarding its steep learning curve, extended operative times, and potential oncologic limitations, particularly in achieving adequate margin clearance and lymph node retrieval[8].

Previous randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses have produced mixed results. Some studies suggest that LPD is non-inferior for short-term outcomes, while others report increased complications in low-volume centers[9-12]. With the global incidence of PDAC rising, particularly among older adults, optimizing surgical outcomes is critical. Early-stage PDAC [tumor (T) 1-2; node (N) 0-1; metastasis (M) 0] provides an ideal group for comparing LPD and OPD. This study aims to evaluate the perioperative and oncologic outcomes of LPD vs OPD in early-stage PDAC, using propensity score matching to control for confounders. Conducted in a high-volume center, this analysis seeks to clarify the feasibility and safety of LPD in this context.

This retrospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of MTI Lady Reading Hospital, Peshawar, Pakistan (Approval No. LRH/GEN-SURG/IRB/2025-047). Between January 2022 and December 2024, we identified 120 patients aged 45-75 years diagnosed with stage I-II PDAC (according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer, 8th edition). Patients undergoing curative PD with confirmed postoperative pathology were included. Exclusion criteria comprised neoadjuvant therapy (n = 10), conversion from LPD to OPD [n = 5; due to intraoperative bleeding (n = 3) or adhesions (n = 2)], and incomplete records (n = 5), resulting in 117 patients for analysis.

Prior to matching, the group consisted of 65 patients who underwent LPD and 52 patients who underwent OPD. Patients were matched 1:1 based on age, sex, body mass index, American Society of Anesthesiologists score, and tumor size using logistic regression with nearest-neighbor matching, a caliper width of 0.2 standard deviations, and no replacement; unmatched patients from the larger group were excluded to ensure balanced pairs. Post-matching, baseline characteristics were well-balanced (standardized mean differences < 0.05 for all variables), as assessed by standardized mean differences and statistical tests. This process resulted in 50 matched pairs (n = 50 LPD and n = 50 OPD), which formed the basis for all subsequent analyses.

Surgeries were performed by five experienced hepatobiliary surgeons, each with a minimum of 100 LPDs. LPD utilized a five-port approach, while OPD employed a standard midline laparotomy. Reconstruction in both groups involved duct-to-mucosa pancreatojejunostomy. The duct-to-mucosa pancreatojejunostomy was performed using interrupted sutures with 5-0 polydioxanone, typically placing 6-8 stitches in a circular manner around the pancreatic duct to ensure precise alignment and minimize leakage. Both groups adhered to identical perioperative protocols, including enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) principles. The ERAS protocol included preoperative patient education and carbohydrate loading; intraoperative goal-directed fluid therapy; postoperative multimodal pain management (primarily epidural analgesia or patient-controlled analgesia with minimized opioids); early mobilization (targeted within 6-12 hours postoperatively); early removal of nasogastric tubes (typically on postoperative day 1 if no gastric distension was present); and progressive oral intake starting with clear liquids on postoperative day 1, advancing to solid food by day 3 as tolerated. Compliance with ERAS elements was monitored via electronic medical records, with overall adherence rates of 85% for mobilization, 92% for nasogastric tube removal, 88% for oral intake progression, and 90% for pain management across both groups (no significant differences between LPD and OPD, P > 0.05).

Primary outcomes included operative time, blood loss, transfusion rate, and length of stay. Intraoperative blood loss was estimated using a standardized method combining suction canister volumes, weighed surgical swabs (with 1 g equivalent to 1 mL of blood), and visual assessment by the surgical and anesthesia teams, as recorded in the operative and anes

Secondary outcomes encompassed complications [overall, severe (Clavien-Dindo grade ≥ III), pancreatic fistula, delayed gastric emptying], as well as specific complications including wound infection, intra-abdominal abscess, bile leak, pulmonary complications, and sepsis; 90-day readmission and mortality; lymph node yield; R0 resection rate; and 24-month OS. Additionally, ERAS-specific metrics were assessed, including time to first mobilization (hours postoperatively), time to first oral intake (days postoperatively), and pain scores (using the Visual Analog Scale on postoperative day 1). Adjuvant chemotherapy was administered postoperatively according to institutional guidelines, primarily gem

Analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 27). Continuous variables were compared using independent t-tests, and categorical variables were compared using χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests. Survival was assessed using Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests; hazard ratios were estimated via Cox proportional hazards regression. Propensity score matching was performed in R (version 4.3.1). A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Post-hoc power calculations (using statsmodels in Python) indicated > 99% power for detecting differences in blood loss (effect size 2.22) and approximately 90% power for length of stay (effect size 0.86), but lower power (approximately 20%-30%) for rare outcomes like mortality and severe complications, based on observed effect sizes and sample size (n = 50 per group). No multivariable adjustments beyond matching were performed, as residual confounding was minimal. Censoring for survival analyses occurred at the last follow-up or non-cancer death, with a median follow-up of 18 months (range 6-36 months).

Following propensity matching, the LPD and OPD groups were well-balanced in terms of key demographic, clinical, and tumor-related variables, with no statistically significant differences observed (all P > 0.05). For example, the mean age was 62.5 ± 7.2 years in the LPD group and 63.1 ± 6.8 years in the OPD group, while the male-to-female ratio was approximately balanced at 54:46 for LPD and 52:48 for OPD (P = 0.89). Similarly, body mass index, tumor size, American Society of Anesthesiologists scores, and comorbidities such as diabetes were comparable between the groups. Detailed values and statistical comparisons are provided in Table 1 for reference.

| Indicator | LPD group (n = 50) | OPD group (n = 50) | t/χ2 | P value |

| Gender (male/female) | 27/23 | 26/24 | 0.02 | 0.89 |

| Age (years) | 62.5 ± 7.2 | 63.1 ± 6.8 | -0.49 | 0.62 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.2 ± 3.1 | 24.5 ± 3.0 | -0.52 | 0.61 |

| Tumor size (cm) | 2.8 ± 0.9 | 2.9 ± 1.0 | -0.38 | 0.71 |

| ASA score (I/II/III) | 2/34/14 | 1/35/14 | 0.45 | 0.80 |

| Diabetes (no/yes) | 36/14 | 35/15 | 0.05 | 0.82 |

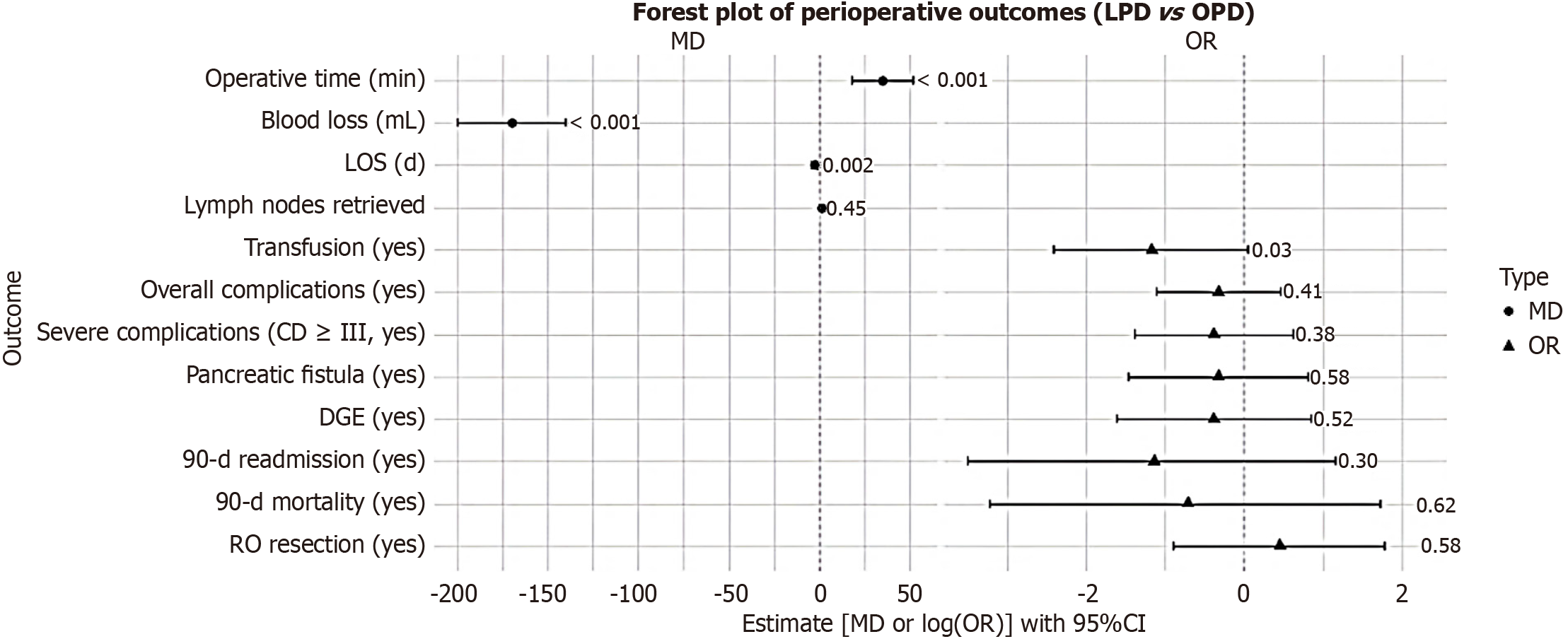

The perioperative outcomes, as comprehensively outlined in Table 2 and visually summarized in Figure 1 (which includes mean differences and odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals), demonstrated several notable differences between LPD and OPD. Specifically, LPD was associated with extended operative times (P < 0.001) but offered clear benefits in terms of decreased blood loss (median 170 mL vs 340 mL; P < 0.001), reduced transfusion requirements (P = 0.03), and abbreviated hospital lengths of stay (P = 0.002). Regarding complications, rates for overall events, severe complications (Clavien-Dindo grade ≥ III), pancreatic fistula, delayed gastric emptying, and additional specific complications - including wound infection, intra-abdominal abscess, bile leak, pulmonary issues, and sepsis - did not differ significantly between the groups (all P > 0.05). Furthermore, ERAS-related metrics highlighted advantages for LPD, such as expedited time to first mobilization (P = 0.001) and earlier initiation of oral intake (P < 0.001). The 90-day readmission and mortality rates also showed no meaningful disparities (P = 0.30 and P = 0.62, respectively).

| Indicator | LPD group (n = 50) | OPD group (n = 50) | t/χ2 | P value | MD/OR (95%CI) |

| Operative time (minutes) | 320 ± 45 | 285 ± 40 | 4.12 | < 0.001 | MD 35 (18.31 to 51.69) |

| Blood loss (mL) | 180 ± 60 | 350 ± 90 | -11.2 | < 0.001 | MD -170 (-199.98 to -140.02) |

| Transfusion (no/yes) | 46/4 | 39/11 | 4.65 | 0.03 | OR 0.31 (0.09 to 1.05) |

| LOS (days) | 12 ± 3 | 15 ± 4 | -3.28 | 0.002 | MD -3 (-4.39 to -1.61) |

| Overall complications (no/yes) | 29/21 | 25/25 | 0.68 | 0.41 | OR 0.72 (0.33 to 1.59) |

| Severe complications (CD ≥ III, no/yes) | 42/8 | 39/11 | 0.77 | 0.38 | OR 0.68 (0.25 to 1.85) |

| Pancreatic fistula (no/yes) | 44/6 | 42/8 | 0.32 | 0.58 | OR 0.72 (0.23 to 2.24) |

| DGE (no/yes) | 45/5 | 43/7 | 0.41 | 0.52 | OR 0.68 (0.20 to 2.32) |

| 90-day readmission (no/yes) | 49/1 | 47/3 | 1.02 | 0.30 | OR 0.32 (0.03 to 3.18) |

| 90-day mortality (no/yes) | 49/1 | 48/2 | 0.24 | 0.62 | OR 0.49 (0.04 to 5.58) |

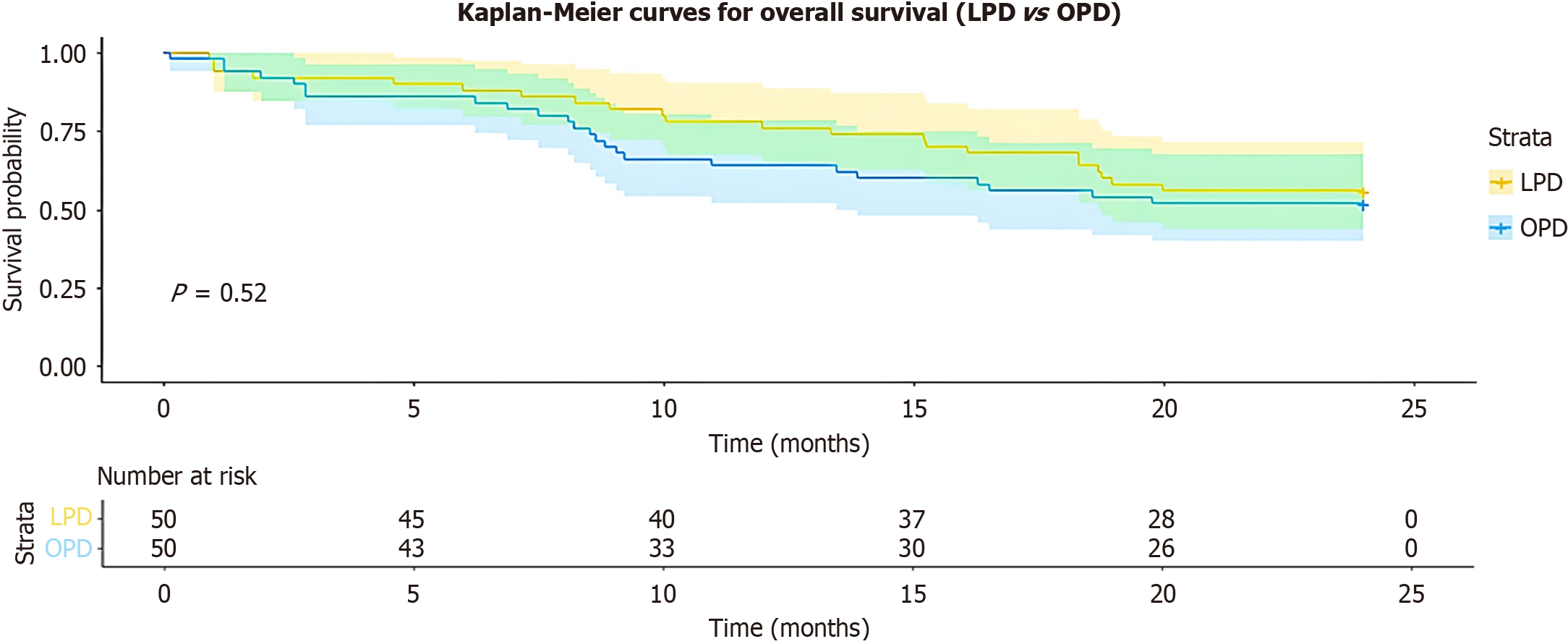

Oncologic outcomes were equivalent between LPD and OPD, with no significant variations noted in lymph node yield (P = 0.45), R0 resection rates (P = 0.56), median OS (22 vs 20 months; log-rank P = 0.65), or 12-month recurrence-free survival (78% vs 72%; P = 0.48), as detailed in Table 3 and illustrated in Figure 2. Adjuvant chemotherapy profiles were likewise similar, encompassing regimens that were primarily gemcitabine-based (gemcitabine monotherapy in 60% of cases, gemcitabine plus capecitabine in 30%, and fluorouracil, leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin in 10%), along with comparable completion rates (84% vs 80%; P = 0.62), a median of 5 cycles completed, and a mean relative dose intensity of 85% (P = 0.72).

| Indicator | LPD group (n = 50) | OPD group (n = 50) | t/χ2 | P value | MD/OR/HR (95%CI) |

| Lymph nodes retrieved | 14 ± 5 | 13 ± 4 | 0.75 | 0.45 | MD 1 (-0.77 to 2.77) |

| R0 resection (no/yes) | 4/46 | 6/44 | 0.34 | 0.56 | OR 1.57 (0.41 to 5.93) |

| Median OS [months (95%CI)] | 22 (19-25) | 20 (17-23) | 0.65 | HR 0.92 (0.65 to 1.31) | |

| 12-month RFS (%) | 78 | 72 | 0.48 | HR 0.78 (0.35 to 1.74) | |

| Adjuvant completion (no/yes) | 8/42 (84%) | 10/40 (80%) | 0.24 | 0.62 | OR 1.31 (0.47 to 3.66) |

Including the five patients converted from LPD to OPD in the LPD group did not significantly alter the primary out

This study compares the perioperative and oncologic outcomes of LPD vs OPD for early-stage PDAC. LPD demonstrated significant perioperative advantages, including reduced blood loss, fewer transfusions, and shorter hospital stays, without apparent differences in oncologic outcomes such as lymph node yield, R0 resection rates, or survival.

The longer operative time for LPD aligns with prior studies, reflecting the technical complexity of intracorporeal reconstruction[6,11]. However, this did not increase complication rates, which is a critical consideration for minimally invasive approaches. The reduction in blood loss and transfusions is particularly noteworthy, as it may decrease risks such as anemia or transfusion-related complications, consistent with findings from meta-analyses[12]. Specific complication rates included wound infection [6% LPD vs 14% OPD; odds ratio (OR) = 0.39, P = 0.11], intra-abdominal abscess (4% vs 6%; OR = 0.65, P = 0.68), bile leak (2% vs 4%; OR = 0.49, P = 0.62), pulmonary complications (8% vs 12%; OR = 0.64, P = 0.41), and sepsis (4% vs 6%; OR = 0.65, P = 0.68); these showed no significant differences but contributed to the overall complication profiles. ERAS metrics favored LPD, with shorter time to first mobilization (8.5 ± 3.2 hours vs 12.4 ± 4.1 hours; MD -3.9 hours, P = 0.001) and earlier oral intake (1.2 ± 0.5 days vs 2.1 ± 0.8 days; MD -0.9 days, P < 0.001).

From an oncologic perspective, the comparable lymph node yield and R0 resection rates suggest LPD’s adequacy in experienced centers, supported by RCTs indicating non-inferiority[13,14]. However, the small sample size and wide confidence intervals (e.g., hazard ratio 0.78 for recurrence-free survival, 95% confidence interval: 0.35-1.74) limit definitive claims of equivalence, and larger studies are needed to establish non-inferiority. The median OS (20-22 months) aligns with outcomes for predominantly gemcitabine-based regimens but is slightly lower than those reported in Western groups using more intensive therapies like fluorouracil, leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin, possibly due to diff

Limitations include the retrospective design, which, despite propensity matching, may not account for unmeasured confounders (e.g., tumor location, carbohydrate antigen 19-9 levels). The sample size constrained power for rare outcomes like mortality (power approximately 20%-30%), and the 18-month median follow-up limits long-term survival ass

LPD appears to offer significant perioperative benefits over open surgery for early-stage PDAC, without evident compromise to oncologic outcomes in this group. These findings support LPD’s selective adoption in high-volume centers with experienced surgeons, particularly for patients without major vascular involvement. Prospective, multicenter studies are needed to confirm non-inferiority, long-term efficacy, and cost-effectiveness.

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the staff and administration of MTI Lady Reading Hospital (Peshawar, Pakistan) for their invaluable support in facilitating data collection and access to the surgical database. We also extend our thanks to the patients whose data contributed to this study, without whom this research would not have been pos

| 1. | Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:229-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5690] [Cited by in RCA: 12788] [Article Influence: 6394.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 2. | Leiphrakpam PD, Chowdhury S, Zhang M, Bajaj V, Dhir M, Are C. Trends in the Global Incidence of Pancreatic Cancer and a Brief Review of its Histologic and Molecular Subtypes. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2025;56:71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 30.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Katona BW, Lubinski J, Pal T, Huzarski T, Foulkes WD, Moller P, Eisen A, Randall Armel S, Neuhausen SL, Raj R, Aeilts A, Singer CF, Bordeleau L, Karlan B, Olopade O, Tung N, Zakalik D, Kotsopoulos J, Fruscio R, Eng C, Sun P, Narod SA; Hereditary Breast Cancer Clinical Study Group. The incidence of pancreatic cancer in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. Cancer. 2025;131:e35666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chang Wu B, Wlodarczyk J, Nourmohammadi Abadchi S, Shababi N, Cameron JL, Harmon JW. Revolutionary transformation lowering the mortality of pancreaticoduodenectomy: a historical review. eGastroenterology. 2023;1:e100014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wang M, Pan S, Qin T, Xu X, Huang X, Liu J, Chen X, Zhao W, Li J, Liu C, Li D, Liu J, Liu Y, Zhou B, Zhu F, Ji S, Cheng H, Li Z, Li J, Tang Y, Peng X, Yu G, Chen W, Ma H, Xiong Y, Meng L, Lu P, Zhang Z, Yu X, Zhang H, Qin R. Short-Term Outcomes Following Laparoscopic vs Open Pancreaticoduodenectomy in Patients With Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg. 2023;158:1245-1253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lee J, Lee J, Hong YS, Lee G, Kang D, Yun J, Jeon YJ, Shin S, Cho JH, Choi YS, Kim J, Zo JI, Shim YM, Guallar E, Cho J, Kim HK. Validation of the IASLC Residual Tumor Classification in Patients With Stage III-N2 Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Undergoing Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy Followed By Surgery. Ann Surg. 2023;277:e1355-e1363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rangwala HS, Fatima H, Ali M, Rangwala BS. Comparing Safety and Efficacy: Laparoscopic vs. Open Pancreaticoduodenectomy for Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Control Trials. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2025;16:432-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Valle V, Pakataridis P, Marchese T, Ferrari C, Chelmis F, Sorotou IN, Gianniou MA, Dimova A, Tcholakov O, Ielpo B. Comparative Analysis of Open, Laparoscopic, and Robotic Pancreaticoduodenectomy: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Medicina (Kaunas). 2025;61:1121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Holmberg M, Radkiewicz C, Strömberg C, Öman M, Ghorbani P, Löhr JM, Sparrelid E. Outcome after surgery for invasive intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasia compared to conventional pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma - A Swedish nationwide register-based study. Pancreatology. 2023;23:90-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Patel VR, Adamson AS, Liu JB, Welch HG. Increasing Incidence and Stable Mortality of Pancreatic Cancer in Young Americans. Ann Intern Med. 2025;178:142-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Park Y, Han YB, Kim J, Kang M, Lee B, Ahn ES, Han S, Kim H, Na HY, Han HS, Yoon YS. Microscopic tumor mapping of post-neoadjuvant therapy pancreatic cancer specimens to predict post-surgical recurrence: A prospective cohort study. Pancreatology. 2024;24:562-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fall S, Souche R, Bardol T, Fabre JM, Borie F; Montpellier-Nimes Digestive Surgery Federation. Laparoscopic versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic or periampullary tumors: a multicenter propensity score-matched comparative study. Surg Endosc. 2025;39:3037-3048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zhang S, Xing Z, Zhao W, Wu H, Yang X, Liu J. Risk factors for postoperative outcomes in laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy: a retrospective cohort study from 2015 to 2023. Gland Surg. 2025;14:1128-1139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Stauffer JA, Hyman D, Porrazzo G, Tice M, Li Z, Almerey T. A propensity score-matched analysis of laparoscopic versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy: Is there value to a laparoscopic approach? Surgery. 2024;175:1162-1167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Anand U, Kodali R, Parasar K, Singh BN, Kant K, Yadav S, Anwar S, Arora A. Comparison of short-term outcomes of open and laparoscopic assisted pancreaticoduodenectomy for periampullary carcinoma: A propensity score-matched analysis. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2024;28:220-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yoon YS, Lee W, Kang CM, Hong T, Shin SH, Lee JW, Hwang DW, Song KB, Kwon JW, Sung MK, Shim IK, Lee JB, Kim SC; for Korean Study Group on Minimally Invasive Pancreatic Surgery (K-MIPS). Laparoscopic versus open pancreatoduodenectomy for periampullary tumors: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Surg. 2024;110:7011-7019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/