Published online Jan 16, 2026. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v18.i1.111395

Revised: August 7, 2025

Accepted: October 31, 2025

Published online: January 16, 2026

Processing time: 200 Days and 18 Hours

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is often diagnosed symptomatically. However, objective assessments such as upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (UGIE) and multichannel intraluminal impedance-pH (MII-pH) testing are essential for accurate diagnosis. The correlation between symptoms and objective findings re

To evaluate UGIE findings in patients with GERD symptoms and correlate them with symptom profiles and MII-pH results.

An observational study was conducted in 209 patients (mean age:

UGIE was performed in 95% of patients, but only 33% had objective evidence of reflux (30% esophagitis, 3% Barrett’s esophagus). Hiatal hernia and gastritis were identified in 52% and 70%, respectively. MII-pH testing was done in 23% of pa

Most patients with GERD symptoms lacked objective evidence of reflux in both endoscopy and MII-pH moni

Core Tip: A significant proportion of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms lack objective evidence of reflux on endoscopy or pH impedance testing. It highlights the need for objective diagnostic tools in evaluating GERD, in addition to symptom-based diagnosis. Future directions should include increasing the availability of endoscopy and pH impedance testing facilities, training of specialists to improve reporting standards, reducing the cost of diagnostic tests, and developing population-specific guidelines and standards. Enhancing diagnostic precision will not only improve patient outcomes and resource utilization in GERD management, but also recognition and appropriate treatment of functional heartburn and reflux hypersensitivity.

- Citation: Wickramasinghe N, Devanarayana NM. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms: Correlating endoscopic findings with symptoms and pH-impedance results. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2026; 18(1): 111395

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v18/i1/111395.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v18.i1.111395

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is defined as a condition in which the gastric contents reflux back into the esophagus, resulting in symptoms and complications[1]. It is a common disease condition worldwide, with prevalence ranging from 5% to 25%[2]. Symptoms of GERD include heartburn and regurgitation, chest pain, bloating, dysphagia, and odynophagia, while esophagitis, strictures, and cancer are a few of its complications[1]. GERD leads to poor quality of life and high health care costs. Suggested underlying pathophysiological mechanisms for GERD include increased frequency of transient lower esophageal sphincter (LES) relaxations, ineffective esophageal motility, hiatus hernia, delayed gastric emptying, gastric stasis, and increased gastric acid secretion. Common recognized risk factors for this condition are diet, lifestyle, obesity, and stress[3].

GERD can be managed by medical and surgical treatment modalities. Medical treatment is mainly focused on acid-lowering drugs such as proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). Anti-reflux surgery is reserved for severe cases of GERD that don’t respond to medical treatment. Treatment-resistant GERD is a major challenge in gastroenterology practice. The main reasons for poor treatment response include misdiagnosis, poor compliance, non-acid reflux, esophageal motility disorders, poor gastric emptying, and associated conditions such as rumination and supra-gastric belching[3].

Diagnosis of GERD involves symptom characteristics, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (UGIE), and pH impedance studies[4,5]. Encountering patients with symptoms of GERD is a common, almost daily occurrence for doctors of almost all specialties. A multitude of other disease conditions, such as functional dyspepsia, rumination, recurrent vomiting, and esophageal motility disorders, can also mimic GERD symptoms[6]. Therefore, it is very important to establish a diagnosis in patients with recurrent symptoms. UGIE and pH impedance studies are key diagnostic tools of GERD, though their correlation with each other and with clinical symptoms remains unclear. The main objective of this study was to evaluate this and shed light on this matter.

The study setting was the National Hospital of Sri Lanka (NHSL) because it is the largest hospital complex in Sri Lanka, with a high patient turnover, which was sufficient to achieve the required sample size. Specialized gastrointestinal (GI) physiology investigation facilities are also available in the Gastroenterology Unit of this hospital.

This study was of 2 years’ duration, from 2021 to 2022.

Patients attending the clinics, GI endoscopy, and GI physiology centers of both the Gastroenterology Unit and the Professorial Surgical Clinic of the NHSL were recruited.

The inclusion criteria were: Age from 18 years to 80 years and patients with symptoms suggestive of GERD scoring > 12.5 on the country-validated GERD screening tool[6].

Bedbound and wheelchair-bound patients and patients who have undergone gastrectomy were excluded from the study.

Given the ambiguity and large variety of medical (with different medications at different dosages and duration regimes as well) and surgical options, an exact prevalence cannot be calculated to determine the sample size of GERD patients to be followed up at the hospital-based study. Given the lowest proportion found of 10% of PPI refractory patients, and an estimated 10% loss to follow-up, the required sample size is 152 patients[7]. We managed to recruit 209 consecutive patients presenting to the hospital with symptoms suggestive of GERD.

The interviewer-administered data collection form had the following components: (1) A questionnaire on demographic and socio-economic characteristics; (2) A country-specific validated screening tool for GERD[6]; (3) A country-specific validated food frequency questionnaire[8]; (4) A country-specific validated physical activity level questionnaire (International Physical Activity Questionnaire)[9]; and (5) Perceived level of stress questionnaire[10]. UGIE, pH impedance testing, and high-resolution manometry (HRM) were performed based on the consultant gastroenterologists’ opinion, and the results were included in the analysis. The Seca 813 portable weighing scale was used to measure the weight, and the Seca 213 stadiometer was used to measure height. Standardized measuring tapes were used to measure other anthropometric measures.

Consecutive patients attending the selected gastroenterology clinics and GI endoscopy, GI physiology centers, were recruited and first screened against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and subsequently using the GERD symptom screening tool[6]. In this screening tool, seven symptoms of GERD, namely heartburn, regurgitation, chest pain, bloating, burping, cough, and dysphagia, are scored on a Likert scale based on severity and frequency. Patients with a total score of more than 12.5 (which is suggestive of GERD) were recruited. The diagnosis of GERD is confirmed by both UGIE and 24-hour pH impedance studies[11,12]. Unfortunately, we did not have the logistics or financial capability to do these tests on all our patients. UGIE, esophageal manometry, and pH impedance monitoring were a part of the patient’s management plan. With the patient’s consent, we obtained data to be used for analysis.

The Olympus 190 Endoscopy System was used in endoscopic procedures. They were performed by skilled endoscopists (consultant gastroenterologist, consultant GI surgeon, and senior registrar in gastroenterology or GI surgery). The reports were screened carefully, and the following information was obtained: Presence of esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, esophageal peptic strictures, adenocarcinoma, hiatal hernia (HH), and gastritis. Since the practice is diverse regarding reporting the grades of esophagitis and HH, the mere presence of esophagitis and HH was recorded, not their grading or severity[13]. Histology reports were recorded when available. However, histology was not routinely done during UGIE in Sri Lanka, and many patients did not have it, despite having esophagitis.

The HRM study was performed according to the Association of Gastrointestinal Physiology Guidelines 2017 and the Chicago Classification version 4.0[14,15] by a qualified medical GI physiologist. The equipment used was a water-perfused system with an HRM catheter [CE4-0061 Solar GI HRM by Laborie, reusable, 22 pressure channels, (1 gastric, 6 cm × 1 cm LES, 15 cm × 2 cm esophageal) diameter 4.2 mm]. The test included two resting periods, ten 5 mL individual swallows, and three multiple rapid swallows. Two blinded, qualified GI physiologists independently analyzed the test recordings of each subject using Laborie Medical Measurement Systems software. Categorization was based on the latest Chicago 4 classification.

Multichannel intraluminal impedance-pH (MII-pH) monitoring was performed according to British Society of Gastroenterology Guidelines[14], using an Ohmega ambulatory recorder and pH and impedance catheter [MMS-6Z2P-A02, 6 impedance channels (2 cm spacing)], 2 pH channels (esophageal and gastric, 6 Fr, by Laborie). The testing was done after stopping the acid-lowering drugs for at least a week. Two qualified GI physiologists independently performed analysis for each subject using the Laborie Medical Measurement Systems software. The 24-hour recording was analyzed, excluding mealtimes and other artifacts, with impedance events marked manually, overriding the automated analysis. Total acid exposure time (AET), symptom index (SI), symptom sensitivity index (SSI), and symptom association probability (SAP) are obtained to help in the diagnosis and classification. AET value of more than 4%, SI and SSI values of more than 50%, and SAP value of more than 95% were taken as abnormal[16-18]. The DeMeester score was taken as abnormal if it exceeded a value of 14.7[19], and the number of refluxes in 24 hours was also obtained.

The classification of patients was done according to the Rome IV criteria and Lyon consensus[16,20]. The main categories diagnosed using endoscopy and MII-pH are erosive reflux disease (ERD), non-ERD (NERD), reflux hypersensitivity (RH), and functional heartburn (FH). Based on the HRM results, esophageal-gastric junction (EGJ) outflow disorders were recognized. According to the Lyon consensus, conclusive evidence for GERD is based on either endoscopic evidence of GERD [Los Angeles (LA) grades C and D esophagitis, long-segment Barrett’s esophagus, or peptic strictures on en

Analysis was done using SPSS 28. The data collected from patient questionnaires and investigations were used to compare the categories. Data are presented as either mean ± SD or n (%). Comparisons were made with Fisher’s exact test and Mann-Whitney U tests, as the results were deemed non-parametric by standard statistical tests. Spearman’s rank correlation was used to explore the associations. P < 0.01 in univariable analysis and P < 0.0003 after Bonferroni correction were considered statistically significant.

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Colombo, approval No. EC-19-091. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants.

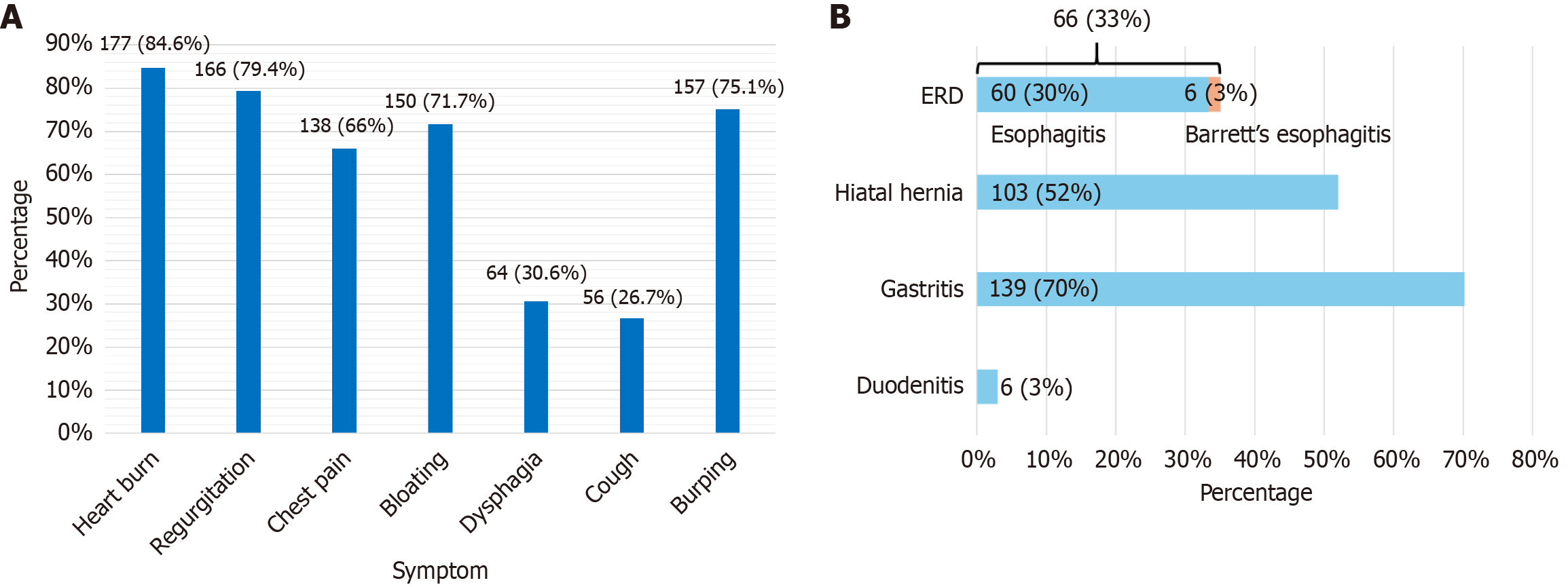

A total of 209 patients aged 18 years to 79 years were recruited, with a mean age of 45.78 years (47.78 ± 15.18, 95% confidence interval: 43.72-47.85), of whom 112 patients (53.6%) were male. Figure 1A presents the frequency of the seven primary symptoms included in the GERD screening tool at the time of recruitment. Among the cohort, 8 patients did not undergo any of the three major investigations (endoscopy, manometry, or MII-pH), while 46 patients underwent all three.

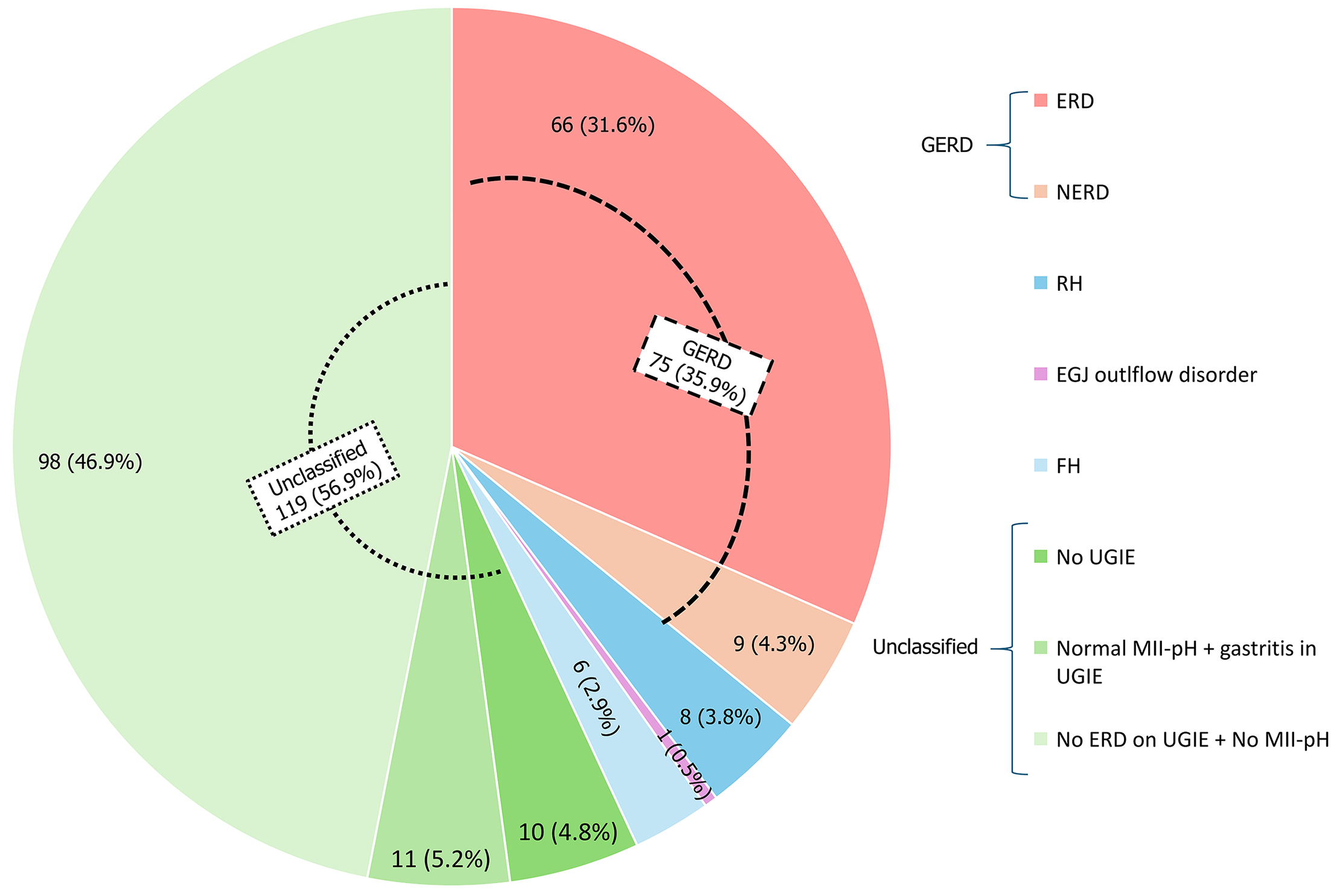

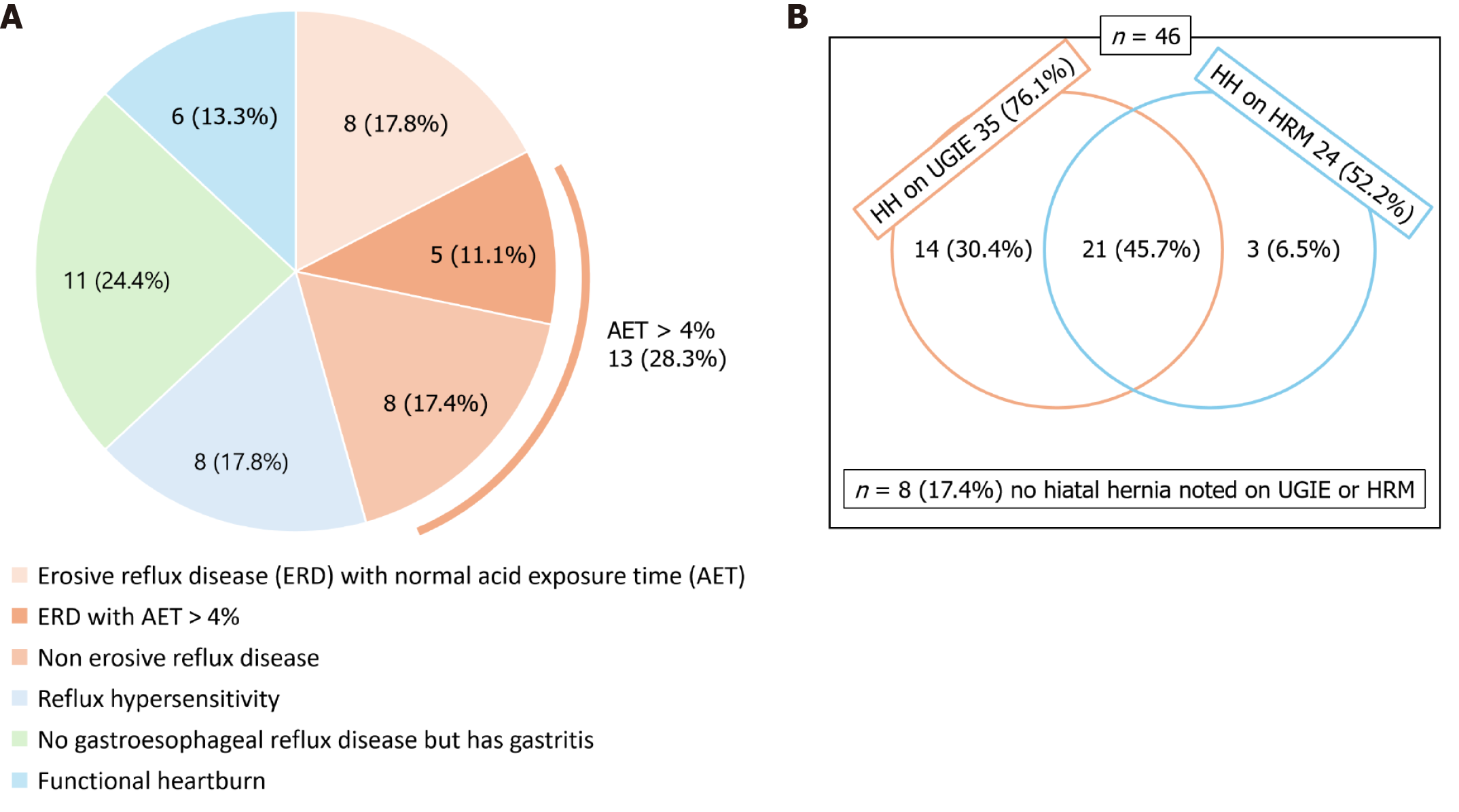

Key findings of 199 patients who underwent UGIE are illustrated in Figure 1B. Peptic strictures, adenocarcinoma, or pharyngeal pathologies were not reported in our study. The diagnostic categorizations for the total cohort (n = 209) and the subgroup who underwent all three investigations (n = 46) are summarized in Figures 2 and 3, respectively.

Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1 provide MII-pH metrics across different diagnostic categories. Notably, all 46 patients had normal oropharyngeal swallow coordination, and no upper esophageal sphincter abnormalities in HRM. When comparing ERD (n = 13, with esophagitis on UGIE) with NERD, with Bonferroni correction, there was no difference in HRM or MII-pH parameters (P > 0.0003). Barrett’s esophagus was absent in all patients. Figure 3A details the proportion of patients with esophagitis who had abnormal AET values. Of the 46 patients, 27 (58.7%) had endoscopically diagnosed gastritis. A P value of 0.003 was noted during the comparison of differences in AET recorded by pH impedance study, between patients with gastritis and those without gastritis, among patients whose AET was > 4% [mean AET was 13.1% ± 2% in those with no gastritis (n = 6), AET was 5.2% ± 1.6% in those with gastritis (n = 7)], which is significant with Bonferroni correction. HH was diagnosed via both UGIE and HRM, with findings presented in Figure 3B. HH was present in 61.6% of patients with AET < 4%.

| Metrics per 24 hours | ERD | NERD | RH | FH | ERD with AET > 4% (n = 5) | AET > 4% (n = 13) | P value (ERD vs NERD)1 | P value (ERD with high AET vs NERD)1 | P value (high AET vs RH)1 | P value (high AET vs FH)1 | P value (FH vs RH)1 |

| Acid exposure time (%) | 4.0 ± 4.3, 1.4-6.5 | 9.2 ± 5.1, 4.9-13.4 | 1.3 ± 1.1, 0.4-2.2 | 1.3 ± 0.9, 0.33-2.2 | 8.4 ± 3.6, 3.9-12.8 | 8.9 ± 4.4, 6.1-11.5 | 0.015 | 0.826 | < 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.948 |

| Total reflux events | 52.6 ± 50.9, 21.8-83.3 | 55.7 ± 33.1, 28-83 | 40.2 ± 32.5, 13-67.3 | 23.6 ± 28.0, -5.8 to 52.9 | 98.1 ± 55.9, 28.7-167.5 | 72.0 ± 46.3, 44-100 | 0.469 | 0.143 | 0.148 | 0.016 | 0.121 |

| SI for impedance refluxes (%) | 24.6 ± 35.1, 3.4-45.8 | 14.7 ± 21.9, -3.6 to 33 | 29.7 ± 23.2, 10.2-49 | 0.2 ± 0.4, 0.2-0.5 | 56.5 ± 39.5, 7.5-105.5 | 30.8 ± 35.3, 9.4-52.1 | 0.481 | 0.038 | 0.510 | 0.079 | 0.002 |

| SSI for impedance refluxes (%) | 13.1 ± 21.3, 0.2-25.9 | 2.8 ± 5.0, | 25.7 ± 21.8, 7.5-43.9 | 4.2 ± 10.2, | 15.3 ± 13.3, -1.2 to 31.9 | 7.6 ± 10.7, 1.1-14.0 | 0.273 | 0.077 | 0.010 | 0.204 | 0.012 |

| SAP for impedance refluxes (%) | 45.1 ± 50.3, 14.6-75.4 | 36.3 ± 50.2, -5.6 to 78 | 96.4 ± 9.0, 88.8-103.9 | 6.5 ± 15.9, | 79.8 ± 44.6, 24.4-135.2 | 53.1 ± 51.2, 22.1-83.9 | 0.433 | 0.036 | 0.111 | 0.078 | 0.001 |

| Distal MNBI (3, 5, 7, 9) | 2452.3 ± 1042.9, 1822-3082 | 1158.3 ± 350.5, 865-1451 | 2526.0 ± 727.5, 1917-3134 | 2561.1 ± 651.7, 1877-3245 | 1751.8 ± 769.1, 796.8-2706.6 | 1386.6 ± 599.3, 1024.4-1748.6 | 0.001 | 0.079 | 0.004 | 0.007 | 0.699 |

| PSPW index (%) | 86.6 ± 57.7, 51.7-121.5 | 61.4 ± 18.5, 45.9-76.8 | 83.3 ± 18.1, 68.2-98.4 | 68.9 ± 30.9, 36.4-101.3 | 61.3 ± 23.8, 31.8-90.7 | 61.4 ± 19.7, 49.4-73.2 | 0.147 | 1.000 | 0.011 | 0.598 | 0.604 |

The post-reflux swallow-induced peristaltic wave index (PSPW-I) was significantly higher in patients with AET < 4% (mean AET in abnormal PSPW-I group: 5.1% ± 4.9% vs normal PSPW-I: 2.56% ± 3.7%, P = 0.021). The average PSPW-I across the cohort was 61%, which meets the recommended cutoff. A significantly higher incidence of patients with > 80 refluxes/24 hours was found in those with abnormal PSPW-I (40%) compared to those with normal PSPW-I (3.2%, P = 0.003). Similar trends were observed for > 40 refluxes/24 hours (66.7% vs 16.1%, P = 0.002).

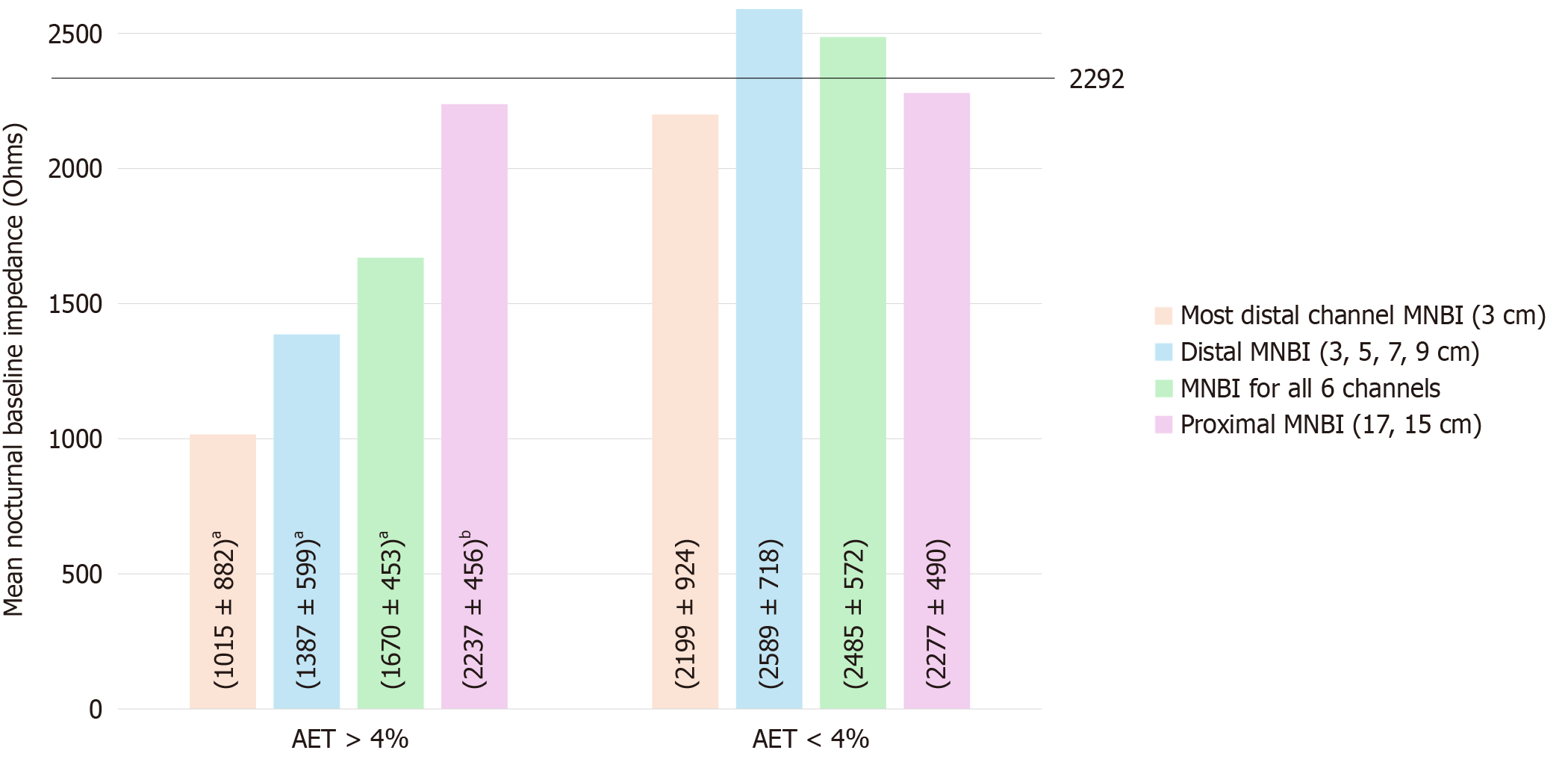

Mean nocturnal baseline impedance (MNBI) values were measured at multiple esophageal levels (3 cm, 5 cm, 7 cm, 9 cm, 15 cm, and 17 cm), including the most distal 3 cm and overall averages. Figure 4 illustrates MNBI differences between patients with AET > 4% and AET < 4%. Although MNBI values were lower in patients without esophagitis, the differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.566 for total, 0.184 for proximal, 0.724 for distal, and 0.542 for most distal MNBI). Similar trends were observed among AET > 4% patients.

A higher percentage of patients with esophagitis had abnormal DeMeester scores compared to those without esophagitis (46.2% vs 30.3%), though the difference was not statistically significant (Fisher’s exact test, P = 0.328).

Table 2 compares demographic and clinical characteristics across NERD, ERD, RH, and FH groups, including total and individual symptom scores. Symptom severity and frequency were scored using the GERD screening tool, and correlations were performed for MII-pH metrics within AET > 4% and RH categories. In the AET > 4% group, heartburn score correlated with PSPW-I (P = 0.007, r = 0.702), regurgitation score correlated with longest reflux time (P = 0.01, r = 0.685), chest pain score correlated with EGJ contractile integral (P = 0.034, r = 0.588), dysphagia score correlated with proximal reflux events (P = 0.031, r = 0.599) and cough score correlated with total reflux events (P = 0.029, r = 0.603). In the RH group, cough score correlated with long acid reflux episodes (P = 0.004, r = 0.875) and proximal reflux events (P = 0.003, r = 0.894), and chest pain score correlated with LES mean resting pressure (P = 0.043, r = 0.722). No significant pattern or difference in the frequency or severity of belching/burping symptoms was observed among GERD, RH, and FH groups. Notably, none of the 46 patients exhibited supragastric belching (SGB) events on MII-pH tracings, as independently reviewed by two analysts.

| Metrics per 24 hours | NERD | ERD with AET > 4% | AET > 4% | RH (n = 8) | FH (n = 6) | P value (ERD with high AET vs NERD) | P value (high AET vs RH) | P value (high AET vs FH) | P value (FH vs RH) |

| Symptom characteristics | |||||||||

| Satisfactory response to anti-reflux treatment | 5 (62.5) | 4 (80) | 9 (69.2) | 5 (62.5) | 3 (50) | 1.0001 | 1.01 | 0.6171 | 1.0001 |

| GERD screening tool score | 56.75 ± 20.6, 39.5-74 | 45.4 ± 14.1, 27.8-62.9 | 52.4 ± 18.6, 41.1-63.6 | 66.3 ± 39.3, 33.4-99 | 52.3 ± 23.0, 28.1-76.5 | 0.3771 | 0.8851 | 1.0001 | 0.7461 |

| Heartburn score | 13.9 ± 7.6, 7.5-20.2 | 9.4 ± 5.6, | 12.2 ± 7.4, 7.7-16.6 | 12.6 ± 3.5, 9.6-15.5 | 11.2 ± 7.5, 3.3-19.0 | 0.3641 | 0.8251 | 0.7861 | 0.3581 |

| Regurgitation score | 9.8 ± 6.9, | 14.8 ± 5.6, 7.8-21.7 | 11.7 ± 6.7, 7.7-15.7 | 13.0 ± 8.6, 5.8-20.1 | 13.3 ± 7.0, 5.9-20.7 | 0.1561 | 0.7651 | 0.5031 | 0.7871 |

| Chest pain score | 10.3 ± 5.6, 5.5-14.9 | 9.4 ± 5.6, | 9.9 ± 5.4, | 10.0 ± 8.6, 2.8-17.1 | 5.0 ± 4.8, | 1.0001 | 0.7411 | 0.0911 | 0.3191 |

| Bloating score | 10.1 ± 6.8, 4.4-15.8 | 1.0 ± 0 | 6.6 ± 7, | 9.4 ± 8.2, | 5.7 ± 7.9, | 0.0071 | 0.3691 | 0.6341 | 0.2801 |

| Dysphagia score | 2.8 ± 3.2, | 3.8 ± 6.3, | 3.2 ± 4.4, 0.48-5.8 | 6.4 ± 7.6, 0.006-12.7 | 4.3 ± 7.7, | 1.0001 | 0.1811 | 0.6511 | 0.5661 |

| Cough score | 4.8 ± 7.3, | 3.2 ± 4.9, | 4.2 ± 6.3, 0.36-7.9 | 5.8 ± 6.8, 0.08-11.4 | 8.0 ± 8.3, | 0.7661 | 0.5251 | 0.2641 | 0.6161 |

| Burping score | 7.0 ± 5.0, | 5.4 ± 1.5, | 6.4 ± 4.0, | 7.8 ± 5.3, | 4.8 ± 4.0, | 0.7091 | 0.6061 | 0.4701 | 0.2881 |

| Factors associated with GERD symptoms | |||||||||

| Age (years) | 38.8 ± 9.9, | 32.8 ± 6.6, | 36.5 ± 8.9, | 34.8 ± 9.9, 26.5-43 | 35.8 ± 9.7, 25.6-46 | 0.1631 | 0.6901 | 0.8601 | 0.7471 |

| Sex (male) | 3 (37.5) | 3 (60) | 6 (46.2) | 4 (50) | 5 (83.3) | 0.5922 | 1.02 | 0.1772 | 0.3012 |

| Married | 5 (62.5) | 2 (40) | 7 (53.8) | 5 (62.5) | 4 (66.7) | 0.5922 | 1.02 | 1.0002 | 1.02 |

| PSS score | 17.0 ± 6.3, 11.7-22.2 | 12.2 ± 1.9, 9.8-14.6 | 15.1 ± 5.5, 11.8-18.5 | 13.9 ± 5.3, 9.4-18.3 | 15.0 ± 3.6, 11.2-18.7 | 0.0551 | 0.4211 | 0.8241 | 0.3931 |

| Abdominal obesity (Asian cutoffs) | 2 ± 25 | 3 ± 60 | 5 ± 38.5 | 3 ± 37.5 | 1 ± 16.7 | 0.2932 | 1.02 | 0.6052 | 0.5802 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.8 ± 4.2, 22.2-29.3 | 26.0 ± 4.7, 29.3-31.9 | 25.9 ± 4.2, 23.3-28.4 | 23.0 ± 3.8, 19.8-26.2 | 22.7 ± 2.5, | 0.7701 | 0.1111 | 0.1141 | 0.9481 |

| Physical activity level (MET minute/ | 211.1 ± 433.3, -151 to 573 | 1076.4 ± 1439.1, 710-2863 | 543.9 ± 995.9, -57.8 to 1145.7 | 914.1 ± 890.1, 169.3-1658 | 3409.0 ± 4040.1, -830 to 7648 | 0.0801 | 0.1091 | 0.0131 | 0.2451 |

| History of abdominal surgery | 2 (25) | 1 (20) | 3 (23.1) | 2 (25) | 1 (16.7) | 1.0002 | 1.0002 | 1.0002 | 1.0002 |

| Those with asthma | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (25) | 2 (33.3) | - | 0.1332 | 0.0882 | 1.0002 |

| Those with diabetes mellitus | 2 (25) | 0 (0) | 2 (15.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.4872 | 0.5052 | 1.0002 | - |

| Caloric intake (kcal) | 2235.0 ± 732.7, 1622-2847 | 1944.4 ± 684.1, 1094.9-2793.8 | 2123.3 ± 700.6, 1699-2546 | 1861.7 ± 539.9, 1410-2313 | 2083.9 ± 219.6, 1853-2314 | 0.3801 | 0.3461 | 0.7921 | 0.5191 |

| Carbohydrate intake (g) | 420.3 ± 141.2, 302-538 | 348.2 ± 132.4, 183.7-512.6 | 392.6 ± 137.1, 309.6-475.4 | 323.4 ± 91.3, 247-399.6 | 349.0 ± 54.0, 292.3-405.7 | 0.3801 | 0.3111 | 0.5991 | 0.6991 |

| Fat intake (g) | 34.9 ± 13.1, 23.9-45.7 | 35.5 ± 18.3, 12.7-58.2 | 35.1 ± 14.5, 26.3-43.9 | 40.9 ± 21.6, 22.8-58.9 | 36.0 ± 8.3, 27.2-44.6 | 1.0001 | 0.7721 | 0.4831 | 0.8971 |

| Protein intake (g) | 55.6 ± 18.5, 40-71 | 61.1 ± 12.9, 45.1-77.1 | 57.7 ± 16.2, 47.8-67.5 | 51.3 ± 19.2, 35.2-67.3 | 51.0 ± 7.8, 42.8-59.2 | 0.6611 | 0.1921 | 0.1881 | 0.5191 |

| Fiber intake (g) | 22.7 ± 11.8, 12.7-32.5 | 20.8 ± 10.1, 8.2-33.3 | 21.9 ± 10.8, 15.4-28.4 | 18.3 ± 10.0, 9.9-26.6 | 22.8 ± 9.5, 12.7-32.8 | 0.6611 | 0.3461 | 0.9301 | 0.3661 |

| Symptoms for spicy food | 6 (75) | 3 (60) | 9 (69.2) | 7 (87.5) | 4 (66.7) | 1.0002 | 0.6062 | 1.0002 | 0.5382 |

| Symptoms for oily food | 5 (62.5) | 3 (60) | 8 (61.5) | 7 (87.5) | 4 (66.7) | 1.0002 | 0.3362 | 1.0002 | 0.5382 |

| Symptoms for wheat-based food | 2 (25) | 2 (40) | 4 (30.8) | 6 (75) | 4 (66.7) | 1.0002 | 0.0802 | 0.3192 | 1.0002 |

| Symptoms for bread | 5 (62.5) | 3 (60) | 8 (61.5) | 6 (75) | 5 (83.3) | 1.0002 | 0.6562 | 0.6052 | 1.0002 |

In this study, we analyzed the UGIE findings in a cohort of Sri Lankan patients with GERD symptoms and correlated them with MII-pH and HRM esophageal manometry findings. Of this cohort, 95% have undergone UGIE, yet only 33% had definitive endoscopic evidence of reflux (30% esophagitis, 3% Barrett’s esophagus). HH was noted in 52% while gastritis was seen in 70%. MII-pH testing was performed in 23% of the patient cohort, but only a quarter of those tested showed significant acid reflux. Of the patients who underwent both MII-pH testing and endoscopy, AET values were higher, and MNBI values were lower in patients with NERD than those with ERD. Of the patients with AET > 4%, gastritis was noted in the majority, with AET values being higher in those without gastritis. A small number of patients with normal AET values and normal symptom association scores had endoscopic evidence of esophagitis.

The demography of the cohort that was studied represented patients with symptoms of GERD, attending the leading tertiary care state hospital in Sri Lanka, who had not responded to standard acid-lowering treatment. The majority were in their forties. This is compatible with the systematic review by Nirwan et al[2], where the highest prevalence was noted in the age group of 35 years to 59 years. Males and females were almost equally represented in a one-to-one ratio, as noted in the same study[2]. With consideration to investigations related to GERD, even a history taken by an expert, such as a gastroenterologist, is of poor sensitivity and specificity compared with pH impedance testing or endoscopy[23]. Therefore, in the current context, a diagnosis of GERD is made using UGIE and MII-pH, supported by the findings of HRM[16].

UGIE is useful in identifying erosive esophagitis and its complications[11,24]. Esophagitis is the most common GERD injury manifestation seen on endoscopy[25,26]. Our study noted that 30% of patients had esophagitis. In a previous Sri Lankan study done in 2007, 64% had endoscopic evidence of esophagitis, which is higher than reported in the current study[18]. Studies show that the presence of esophagitis can also depend on PPI treatment status, where 30% of treatment-naïve patients with heartburn had esophagitis, compared to 10% who were already on PPI[27,28]. In the current study, all patients were already on PPIs, and this may account for the lower prevalence of esophagitis. Barrett’s esophagus was observed in 3% of our patients, which is comparable to previous studies (4%-8%)[29,30]. While histology taken during UGIE has its uses[31], systematic biopsies are not an essential factor in the diagnosis and management of GERD[32]. LA grades C and D, Barrett’s esophagus, and acid strictures are the confirmatory evidence obtained for a diagnosis of GERD[33]. An issue we identified as problematic when analyzing patient reports for our research was the lack of grading for esophagitis. This made it difficult for us to categorize patients as recommended in the Lyon consensus, especially for the category of FH. This is discussed in detail in further below.

Gastritis was noted to be found in 70% of our cohort, which is comparable to 69% reported in a study with a similar setting in Kerala, India[34]. However, there are doubts regarding the accuracy of endoscopic diagnosis related to over-observation of gastritis, as detection and diagnosis by endoscopy have wide variability depending on the endoscopist[35,36]. Despite the large percentage of gastritis seen (over 70%) during the UGIE, no secondary test for identifying Helicobacter pylori, such as the Helicobacter pylori breath test, was available during the study period at NHSL. And only two patients were prescribed Helicobacter pylori eradication treatment. This is due to the unavailability of these drug combinations in the government sector.

HH has a strong association with GERD[37]. HH was noted in more than half of our patients. This is much higher than the 6% reported in a previous study in Kerala, India[34]. In another study, almost all patients who had severe GERD had a HH[38]. HHs disrupt the LES from working with the diaphragm, allowing acid reflux to occur[39]. Furthermore, it is suggested that many with mild GERD might not have a detectable HH, due to HH occurring intermittently or being too short and undetectable on endoscopy[40].

MII-pH plays an important role in GERD diagnosis. For lower grades of esophagitis, such as LA grade B, sometimes medical treatment can even be started, but for further management, such as anti-reflux surgery, confirming GERD by MII-pH is mandatory[41-43]. pH impedance is highly sensitive and specific in diagnosing GERD and in differentiating GERD from FH and RH[11,12]. However, only 23% of our patients with GERD symptoms underwent MII-pH testing. According to management guidelines, if UGIE does not reveal evidence of reflux, the next step is to investigate with MII-pH and manometry. However, this is not diligently practiced in Sri Lanka, as seen with our results. This is due to several reasons. First, this could be due to the unavailability of investigation facilities. At the time of the study, this investigation facility was available in the Gastroenterology Unit of NHSL and one private sector hospital close by. Second, the coronavirus disease pandemic, 2019, reduced the number of patients being referred to MII-pH. Third, the financial crisis in Sri Lanka in 2022 decreased the availability of pH impedance catheters.

In the previous study done in 2007 in Sri Lanka, where both UGIE and pH monitoring (not MII-pH) were conducted in patients with GERD symptoms, 31% were noted to have a high AET[18]. They also noted that the association between the presence of esophagitis and pH findings is poor. Though 64% of patients had esophagitis, AET only increased in 36% of them. This study further warrants the need for increased use of MII-pH in our patients despite positive UGIE for ERD[18]. The overdiagnosis of esophagitis in the previous study may be due to a lack of grading. In this study, we analyzed MII-pH results with AET > 4% as the cutoff for significant acid reflux. However, the Lyon consensus recommends that an AET < 4% is considered normal, while > 6% is considered abnormal, with the numbers in between being inconclusive until proven with adjunct evidence such as abnormal reflux episode numbers[16]. However, there are many limitations regarding diagnosis via AET, as cut-off values have been rebutted or contradicted by research done worldwide, with high variability in studies that calculated normal values for AET[12,42].

In 2020, Sifrim et al[17] analyzed 391 tracings collected from many studies worldwide. These MII-pH studies were done using two different systems, namely Diversatek (United States) and Laborie (Netherlands). Differences in AET normative thresholds were noted to be significant between these two systems, with the cut-off being 2.8% and 5% in Diversatek and Laborie, respectively. Reflux episodes were noted to be fewer in Diversetek (55 per 24 hours) than in the other (78 per 24 hours)[17]. MII-pH also had many regional differences, which were further confounded by the different systems used in different countries[17].

Cut-offs and normal values for MII-pH are further controversial due to other reasons as well. One is that their values rely on very small cohorts of healthy volunteers from only a few countries[43,44]. Another reason is that there is significant inter-reviewer variability due to technical issues related to analysis, such as artifacts and variable ideas regarding the identification of a reflux event[45,46]. Other reasons given are due to the differences in methods used to perform the test, changes the patients make in their lifestyle during the 24 hours of the test, excessive salivation induced by the catheter, and even reduced acidity of gastric secretions due to Helicobacter pylori infection[47-49]. Some experts now recommend lower AET values to diagnose GERD than the Lyon consensus, going as low as 3.2%[50,51]. In a study done in 2005 in Sri Lanka using 12 healthy subjects, an AET of 3.9% was found to be at the 95th percentile of normal Sri Lankan values[16,52]. Given all these factors, we decided to use an AET of 4% as our cut-off point.

Savarino et al[53] summarized the findings of several studies from 2006 to 2019, where 3390 European patients with GERD symptoms were studied with UGIE and MII-pH off-PPI, showing ERD, NERD, RH, and FH to be in proportions of 13%, 40%, 36%, and 24%, respectively. Other studies also had varying proportions depending on the inclusion criteria[54]. These categories are compared in our study participants, as seen in Table 2. Meanwhile, Table 3 summarizes the key findings from the present study and compares them with selected international studies.

Due to the limited numbers in the ERD, RH, and FH categories, we did not make any statistical comparisons between the categories. However, certain trends could be observed. Patients with ERD were the oldest patients, with NERD being the next. The age difference between ERD and NERD groups is conflicting, with a study in Turkey noting that NERD patients are older[55], while another study in Singapore noted that ERD patients were significantly older[56]. Meanwhile, studies have shown that symptom severity in FH patients is inversely related to age, and that it is the opposite for NERD[57].

Studies have shown that ERD patients generally suffer from symptoms longer than NERD patients, and have more severe symptoms that may be associated with exposure to acid, causing severe mucosal damage[58]. However, we did not observe such a difference. When comparing the duration of symptoms between GERD, RH, and FH, there are different views. Some believe that patients with FH have symptoms for a longer duration[22], while others believe that psychological disturbances associated with FH result in higher healthcare seeking, mimicking more severe and prolonged disease[59]. In contrast to this, our patients with ERD and NERD had a longer duration of disease than FH. We recruited patients from a specialized tertiary care center, which receives a subset of patients with more severe and prolonged disease. This may account for the results observed in our study.

It is also well known that symptom characteristics are poor predictors of these different disease manifestations[60]. However, the consensus is that typical GERD symptoms (heartburn and regurgitation) are likely to be more common in GERD, while atypical symptoms are more common in patients with FH[61]. FH and RH patients are also more likely to have dyspeptic symptoms such as bloating, nausea, and fullness after meals, similar to functional dyspepsia[62]. In our study, the presence of nighttime symptoms was also similar between the categories, in contrast to a previous study that showed more sleep disturbances in ERD than in NERD[63]. In another study, patients with GERD had more sleep disturbances than those with FH[64]. Interestingly, nausea and vomiting are common in RH and FH compared to NERD and ERD[62]. In the GERD questionnaire, a widely accepted GERD screening tool questionnaire, negative marks, which lead to a diagnosis away from GERD, are given for the presence of nausea or vomiting[23]. In contrast, some studies have shown nausea to be a symptom in patients with even pH-proven GERD[65].

When looking at the MII-pH and endoscopy results of our patients with GERD symptoms, in contrast to the common belief that esophageal injury is related to the severity of acid reflux[66], AET was slightly higher in patients with NERD compared to ERD, though not statistically significant. This is compatible with what is reported by Martinez et al[54]. The development of esophagitis is said to be not purely due to acid injury but also because of cytokine-induced inflammation, and this probably contributes to the lower AET in our patients with ERD[67]. Many factors contribute to the development of esophagitis in addition to direct exposure to acids, such as chemical injury caused by refluxed contents, bile salts, and other erosive and noxious material, and acid-mediated inflammation mediated through cytokines (interleukin-8, interleukin-1β, and interleukin 6) and nociceptors such as protease-activated receptor 2[68-72]. The already inflamed esophageal mucosa in patients with ERD is probably more sensitive to acid and has a lower symptom threshold, and therefore, ERD patients are likely to develop GERD symptoms with less severe AET[73].

Meanwhile, the characteristics of acid reflux can differ. According to Savarino et al[42], the percentage of proximal acid reflux is higher in ERD patients. This was noted amongst our patients as well. Even the total number of acid reflux events was quite high among patients with ERD whose AET was > 4%, though the difference was insignificant. This reflected the findings of a previous study[12]. Reflux events were lower in patients with RH and FH, though a statistically significant difference was found only between patients with high AET values and FH. It was also interesting to note that the absolute number of non-acid refluxes was normal in patients with FH.

Of patients diagnosed with ERD, 61.5% had no abnormal AET. This mirrored the results in the Sri Lankan study in 2007, where 63.6% of the patients with esophagitis on endoscopy (once again not graded) had no abnormal (> 3.9%) AET[18]. Of our 8 patients with esophagitis but with normal AET, only one patient had an abnormal DeMeester score and more than 40 refluxes per 24 hours; the rest were normal. The symptom association indexes were negative in all, while MNBI and PSPW-I were abnormal in one patient each. This leads to a diagnostic dilemma, as when endoscopy reveals mucosal inflammation, the diagnosis of ERD is relatively certain, and more testing or MII-pH is not generally mandated or done in usual practice[42,74].

False negatives during diagnosis using AET have been noted to occur in almost 20% of patients with esophagitis, and AET does not seem to correlate well with endoscopic findings[42,75]. A study by Schlesinger et al[76] showed that over 29% of patients with ERD had normal MII-pH metrics, while a study by Vitale et al[77] also showed that 23% of patients with esophagitis had normal results. There can be several reasons for this phenomenon. A study by Branicki et al[78] has demonstrated that 24-hour MII-pH monitoring is more sensitive in an outpatient setting than inpatients. They postulated that by enabling the patient to do their normal daily work, factors such as mental stress related to occupation and habits such as cigarette smoking may induce more refluxes[78].

Other reasons suggested by scientists for AET to be normal in esophagitis patients would be pancreaticobiliary reflux, which is alkaline in nature[79,80], excess salivary secretion due to the catheter in situ[81], and decreased parietal cell acid production in elderly patients[82]. Studies have shown that since the number of gastric parietal cells is less in Asian subjects than in those in the West, the acid secretion is less in Asians[51]. Even in non-acid reflux (pH up to 6), the proteolytic activity of pepsins in the refluxate can cause esophageal mucosal damage, inhibiting the healing process[83]. There are other possible contributors to esophagitis in ERD patients with normal AET[84,85]. Recently, eosinophilic esophagitis has been recognized as an important differential diagnosis for reflux esophagitis[86,87]. However, since biopsies were not taken in our study, we were not able to elaborate on this. Helicobacter pylori is also said to reduce the acidity of gastric secretions[88]. However, since none of our patients were tested for the presence of Helicobacter pylori or underwent any eradication treatment for it, we could not assess the impact of this infection.

In this study, we looked at the value of some newer metrics, such as the PSPW index and MNBI. Frazzoni et al[89] postulated that PSPW-I and MNBI are better at distinguishing NERD than AET. However, their definition of NERD is problematic, as NERD was defined as a 6-month history of GERD symptoms that were resolved repeatedly with a PPI course. In our study, out of 13 patients with AET > 4%, PSPW-I was abnormally low in 6 (46.2%), while MNBI was abnormally low in 12 (92.3%) of patients. There are several mechanisms to clear or neutralize refluxed acid. Secondary peristalsis, swallow-related primary peristalsis triggered by refluxate, and neutralization of acid by saliva are the main mechanisms. Swallow-related primary peristalsis triggered by reflux is assessed using PSPW-I, and it is an indirect measure of acid clearance. The PSPW-I is the percentage of refluxes followed by a swallow pattern within 30 seconds of a reflux[89]. A low PSPW-I is seen in GERD patients[90], and an index of less than 61% is said to be suggestive of GERD[50]. In the current study, in the group with abnormal PSPW, there was a higher percentage of patients with more than 80 and more than 40 refluxes per 24 hours. This mirrors the results of studies done so far[89]. Patients with ERD are said to have a lower PSPW-I than NERD[91]. Though not significant, patients with ERD had a higher percentage of abnormal PSPW-I than NERD in our study. The number of reflux episodes lasting more than 5 minutes and the duration of the longest reflux episode recorded are two indirect parameters of esophageal clearance. These metrics were higher among our patients whose PSPW-I was abnormally low[47,92]. Furthermore, the percentage of proximal events also increased among those with low PSPW-I in our patients.

Baseline impedance is a value that correlates with esophageal permeability[93]. It is calculated as an MNBI measured from impedance tracings taken from three ten-minute periods of impedance tracing spaced one hour apart during sleep[94]. Studies done between healthy controls and GERD patients have shown a tentative cutoff of 2293 Ohms, and less than that is considered abnormal[17]. Averaging the MNBI values of channels at 3 cm, 5 cm, 7 cm, and 9 cm situated above gives the distal MNBI, while channels at 15 cm and 17 cm above the LES give the proximal MNBI, and averaging all gives the total MNBI[95]. We also measured the MNBI of the most distal channel in our study. All four of the above-described metrics were lower in patients with NERD, indicating higher acid exposure. There was a difference in all the above metrics between NERD and RH, as well as between NERD and FH. These mirror the results of studies done worldwide[89,96]. Our patients with AET > 4% had lower total, distal, and most distal MNBI values. Total, distal, and most distal MNBI values also correlated with AET and the number of total refluxes per 24 hours. Similar results were seen in a study done by Kessing et al[97]. While studies have shown that those with esophagitis have lower values of MNBI metrics[98], our findings did not reflect that.

Studies using multivariate logistic regression analysis have found PSPW-I and MNBI to be independent predictors of RH[99]. The correlation between reduced PSPW-I and reduced MNBI values is thought to be a cause of the impaired clearance of refluxed acid, which consequently leads to a stasis of refluxate, causing mucosal damage[89]. PSPW-I and MNBI are also thought to have an advantage in diagnosing RH in patients with normal AET[50,100]. It is thought that the above explanation and the association between PSPW-I and MNBI with symptom indices suggest that RH is a part of the GERD spectrum and not a part of functional disorders[89]. Due to the small number of patients diagnosed with RH, we could not assess the value of these parameters in our patients. However, a considerable proportion of our patients with normal AET did have abnormal PSPW-I or MNBI while their symptom indices were normal.

Whether the DeMeester score is useful or not in the diagnosis is a matter of contention, with studies both for and against it[33,47,101]. False negatives are thought to occur due to catheter-induced hypersalivation and Helicobacter pylori infection-induced gastric alkalization, which reduces the effects of some of the components that make up the DeMeester score, like the number of acid refluxes and longest acid reflux times[47]. Our findings were not significant.

Symptom indices are another set of metrics from MII-pH monitoring that describe the temporal relationship between symptoms and documented reflux episodes[102]. SI is the percentage of symptoms associated with an episode of reflux, while the SSI is the percentage of refluxes associated with symptoms. An SI and SSI of more than 50% is considered abnormal[103]. SAP, meanwhile, is computed using more complicated statistical analysis and describes the probability of reflux to be associated with symptoms[104]. An SAP of more than 95% is considered a positive sign of symptom association[105]. SI and SAP are complementary, and a combination of both positive SI and SAP provides the best evidence of symptom association[16,106]. Positive SAP and SI metrics were found in 25% and 80% of our NERD and ERD patients, respectively, whereas other studies with larger samples have shown proportions as high as 96% and 93%[12].

The RH diagnostic criteria include typical GERD symptoms, confirmation of the absence of ERD or eosinophilic esophagitis by endoscopy, absence of a major type of esophageal disorder, normal AET, and, more importantly, positive symptom association as evidenced by SI and SAP metrics on MII-pH[107]. Despite the absence of overt esophagitis on endoscopy, microscopic esophagitis is seen in patients with RH[27]. The crux of RH diagnosis depends on a positive symptom association via MII-pH[21]. A major problem with this is that these indices are very patient-dependent, with patients sometimes not perceiving GERD symptoms during the study period, or there being an inaccurate recording of the symptoms[108]. RH patients may also be characterized by refractory heartburn. A systematic review conducted in 2010 of 19 studies showed that around 30% to 60% of patients with diagnosed RH reported suffering from persistent GERD symptoms despite being on PPI[109]. In a study done in Italy by de Bortoli et al[100], almost one-third of patients with GERD symptoms were diagnosed with RH. Some other studies have estimated that up to 75% of patients with refractory GERD may have RH instead of ERD or NERD[22].

Symptom association metrics such as SI and SAP can be computed using pH-only refluxes as well as impedance refluxes, which incorporate both acidic and non-acidic refluxes. Reflux events identified by impedance are recommended to be used for symptom indices, and not solely from pH testing, due to the increased sensitivity[110]. A study by Savarino et al[111], with 150 patients with typical GERD symptoms and normal endoscopy, noted that monitoring non-acid reflux, which causes symptoms, reduced the proportion of patients classified as FH from 43% to 26%. We, too, included SI, SSI, and SAP values calculated for pH refluxes as well as for comparison with those values for impedance refluxes, though our findings were not significant.

In an elegant study by Weijenborg et al[112], where electrical tissue impedance spectroscopy was used to measure mucosal integrity, it was found that sensitivity to acid is increased in patients with GERD and is associated with abnormal esophageal mucosal integrity. Predictably, SI and SAP (for impedances) were higher in our patients with ERD than with NERD. The GERD screening tool score and salient MII-pH and HRM metrics were compared between patients with normal and abnormal symptom indices. We did not check for significance due to the size disparities of the categories to be compared. However, AET and other MII-pH and HRM metrics were more likely to be abnormal in patients with abnormal symptom indices. Kohata et al[113] noted that proximal migration was significantly higher in symptomatic refluxes than in asymptomatic refluxes, suggesting that the level of reflux migration may play a role in treatment-refractory patients. We, too, noted a considerable increase in proximal reflux in patients with positive symptom association indices.

In the study by Savarino et al[42], a positive SAP for typical GERD symptoms was found in 96% of 168 NERD patients and 93% of 58 ERD patients. Surprisingly, in our study, only a small proportion of patients had abnormal symptom association indices in patients who had an AET > 4% as well as an AET > 6%. For example, only 46.2% of our 13 patients with AET > 4% had an abnormal SAP (impedance). This could be a possible indication that even patients with true GERD could be suffering from the same pathophysiological mechanisms that lead to FH. Some of these could be factors related to abnormal motility[114], visceral hypersensitivity[115], alteration of the GI immune system[116], gut microbial dysbiosis[117], factors related to food such as gluten and lactose[118,119], and most importantly, psychosocial factors affecting the gut-brain axis[119,120]. It would be interesting to follow up on patients with abnormal symptom association indices after anti-reflux surgery or after PPI medication to see the satisfaction rate. However, this is beyond the scope of our research. Given the number of studies showing variations and patterns related to perceived symptoms and definite metrics, this is indeed an interesting area to do more research to form an algorithm for symptom-based diagnosis[121-124].

Belching syndrome or SGB syndrome is recognized differential diagnosis for GERD, which can be diagnosed by identifying belching patterns on impedance tracings in MII-pH[16]. While gastric belching is considered a physiological act to vent swallowed air from the stomach, SGB is a pathological behavior where the air is sucked into the esophagus and then released through the pharynx once again[125]. While up to 30 episodes of gastric belching per 24 hours are considered normal[126], more than 13 SGB episodes per 24 hours are considered abnormal[127]. In a study done in the United Kingdom, a range of 0 to 15 SGB episodes (mean: 3, median: 0) was noted in 40 healthy volunteers[127]. They noted the prevalence of 3.4% of excessive SGB in patients who underwent MII-pH testing, and a prevalence of excessive SGB of 35% in PPI-refractory GERD patients[127]. Another study found that almost 50% of patients with GERD also had SGB[128]. However, surprisingly, we did not find any patients with excessive belching or SGB. There were no SGB episodes in the MII-pH tracing of 46 patients, despite being analyzed by two independent reviewers. The reason for this phenomenon cannot be postulated by us. It is thought that Asians might have a lower prevalence of SGB. A study comparing British subjects with reflux symptoms with those of the Japanese found that the Japanese have significantly lower excessive SGB (18.5% vs 36.1%)[129]. We could not find similar studies regarding SGB prevalence in neighboring countries such as India, though a few case studies were available. While studies have noted that patients with functional dyspepsia have increased belching and burping symptoms[130], our study did not note any pattern or significant difference between GERD, RH, and FH patients in terms of the frequency or severity of belching and burping symptoms reported by patients.

Factors associated with GERD, RH, and FH were also studied, despite our limited numbers. We attempted to shed light on certain factors associated with GERD, such as age, sex, obesity, physical activity level, stress, nutritional factors, symptoms for certain types of food, marital status, abdominal surgery, and diseases such as asthma and diabetes mellitus[2,131]. Regarding gender differences, males were noted to have a higher AET, increased reflux episodes, and even a lower MNBI[17]. Our study also noted a higher AET, an increased number of refluxes, increased proximal refluxes, and more symptoms in males, though the MNBI and PSPW-I were lower in females. Interestingly, women scored higher on symptom indices. Similar studies elsewhere have shown the reverse, although their results, too, like ours, were insignificant[132]. Studies worldwide show that FH patients also have a higher level of anxiety, which is another contributor to the increased symptoms in GERD[133,134]. However, in our study, the perceived level of stress score across the ERD, NERD, RH, and FH patients was almost the same. This could be due to the small sample size of each category and the fact that symptoms in ERD and NERD can affect the quality of life of affected individuals[135].

Regarding the strengths of this research, it is the first comprehensive study related to MII-pH and HRM to be published since the year 2007 in Sri Lanka. However, that study was only done using pH metrics with no impedance data available and was therefore unable to detect non-acid refluxes[18]. Our study is the first Sri Lankan study to analyze esophageal luminal impedance data in the country. We have followed the most up-to-date protocols regarding HRM and MII-pH. Therefore, the results of our study can be compared with international research as well. We also calculated newer metrics such as MNBI and PSPW-I values for Sri Lankan patients.

First, the relatively small sample size, particularly for the subgroup that underwent MII-pH testing, limits the statistical power and the ability to detect less common findings such as SGB. Temporal factors such as the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic and Sri Lanka’s concurrent economic crisis significantly influenced patient selection and diagnostic testing availability. Thus, the number of study participants was greatly affected. However, similar studies have been done where the sample sizes have been around 25 to 30 participants, and several associations have been made for MII-pH metrics satisfactorily[113,136].

Second, given that 78% of patients did not undergo MII-pH testing, we acknowledge the potential for selection bias. To address this, we compared the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients who underwent MII-pH testing with those who did not. No significant differences were observed, suggesting that the subgroup tested was broadly representative of the larger cohort, although the possibility of unmeasured confounding remains. The subgroup analyses are severely underpowered with groups as small as n = 5. Therefore, the comparisons should be considered as exploratory due to insufficient power. We acknowledge that the subgroup analyses conducted in this study are exploratory and primarily intended to generate hypotheses rather than draw definitive conclusions. Given the limited sample size within certain subgroups, these findings should be interpreted with caution.

Thirdly, only patients referred to for advanced investigations at a tertiary care center were included, which may not represent the broader GERD population.

Fourth, although all endoscopies were performed by trained personnel, variations in endoscopy technique and reporting may have affected consistency, as formal standardization protocols were not uniformly implemented. The diagnosis of esophagitis through endoscopy can vary depending on the skill and experience of the endoscopist, as well as other factors such as the quality of the equipment used and the technique employed during the procedure[13,36]. Due to multiple reasons, including a lack of uniformity, many endoscopy reports did not have the grading of esophagitis, despite a diagnosis of reflux esophagitis. LA grades A and B are the most common reflux esophagitis found in studies, especially in Asian studies, where almost 95% to 100% of patients with esophagitis were of LA grade A and B[137,138]. Rigidly categorizing patients according to gradings has also been shown to be faulty, as seen by a 2-year follow-up study of 3894 patients with GERD, where progression and regression between the LA gradings were seen with time, further proving that ERD, or for that matter, NERD, is not a disease that can be categorized[139]. Furthermore, most of the patients diagnosed with reflux esophagitis did not have a biopsy to confirm the diagnosis. It is reported that endoscopy without histology is sufficient for diagnosing erosive esophagitis, and systematic biopsies are not a necessary factor in the management of GERD[32,140]. However, histology can provide information on any eosinophilic esophagitis, intestinal metaplasia, or potential malignancy, which are differential diagnoses for GERD[31], and we could not include these conditions in our sample.

Finally, due to the single-center design and the demographic characteristics of the study population, the generalizability of findings to other populations, especially outside of Sri Lanka or South Asia, may be limited.

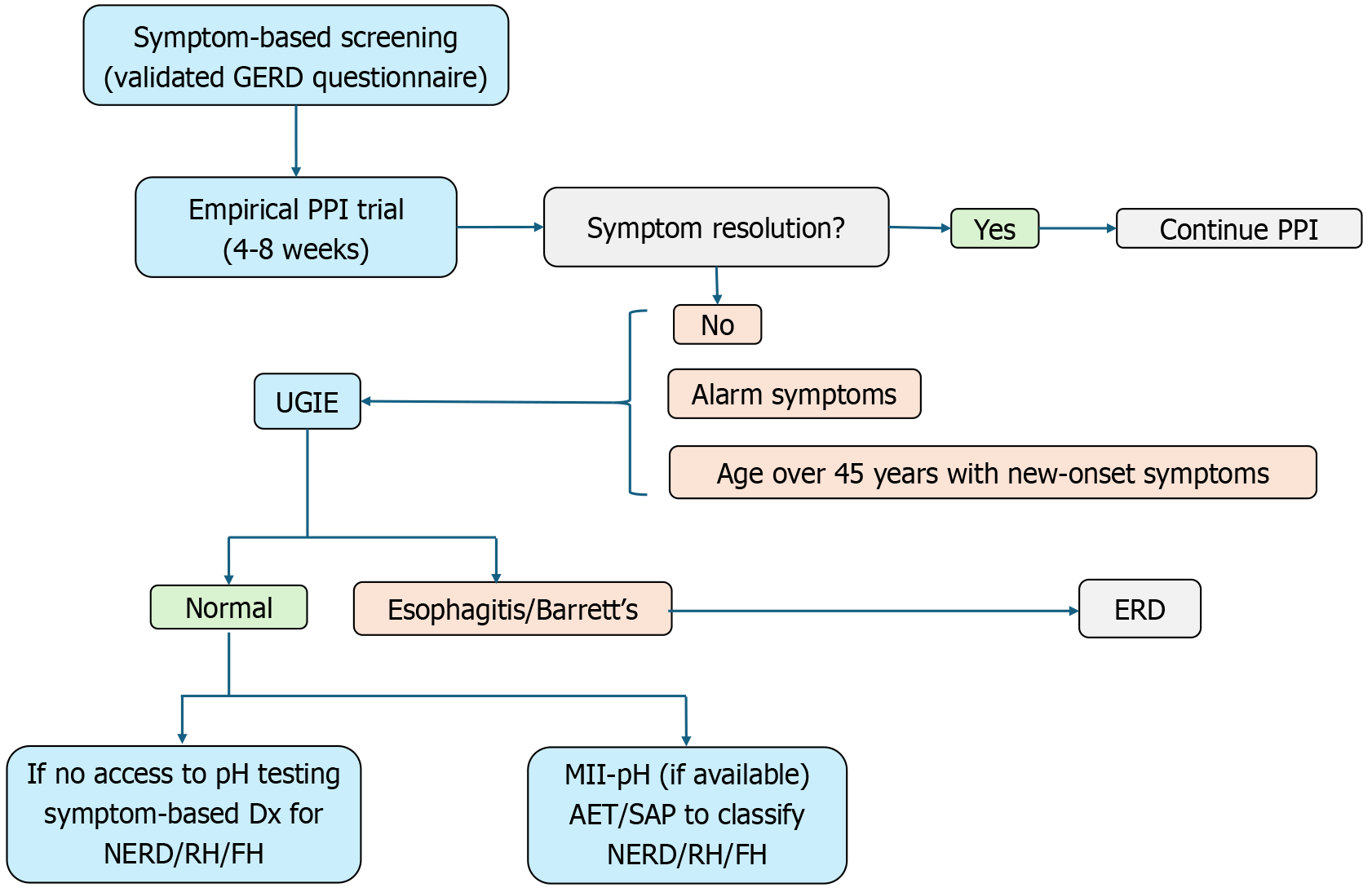

Based on our findings and existing clinical guidelines, we propose a pragmatic diagnostic algorithm for GERD that is adaptable to resource-limited settings, as seen in Figure 5. The first step involves symptom-based screening using a validated GERD questionnaire. In our study, a score of > 12.5 was used to define clinically significant GERD symptoms. Patients without alarm features may be initiated on a therapeutic trial of PPIs for 4-8 weeks. Symptom resolution following the PPI trial supports a presumptive diagnosis of GERD, and patients may continue with maintenance or on-demand therapy. For those with persistent or recurrent symptoms, UGIE should be performed, especially in the presence of alarm features such as dysphagia, weight loss, GI bleeding, anemia, or age over 45 years with new-onset symptoms. In our study, endoscopic evidence of GERD (esophagitis or Barrett’s esophagus) was observed in only 33% of patients, highlighting that many symptomatic individuals may have non-erosive forms of reflux. If endoscopy findings are normal and symptoms persist despite PPI therapy, further evaluation should focus on distinguishing between NERD, RH, and FH. In settings where MII-pH testing is unavailable, as is common in many low- and middle-income countries, a clinical diagnosis based on symptom characteristics and treatment response may be the only feasible approach. If MII-pH is available, it should be reserved for patients with refractory symptoms, allowing differentiation based on acid AET and symptom correlation metrics. Our study also noted a complete absence of SGB among tested patients, which may suggest a lower prevalence of behavioral belching disorders in South Asian populations. Therefore, routine screening for SGB in similar settings may not be warranted unless specifically indicated.

This study demonstrates the notable discordance between GERD symptoms and objective diagnostic findings on endoscopy and MII-pH testing. Our data reinforces that a substantial proportion of symptomatic patients lack con

| 1. | Nebel OT, Fornes MF, Castell DO. Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux: incidence and precipitating factors. Am J Dig Dis. 1976;21:953-956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 590] [Cited by in RCA: 541] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nirwan JS, Hasan SS, Babar ZU, Conway BR, Ghori MU. Global Prevalence and Risk Factors of Gastro-oesophageal Reflux Disease (GORD): Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2020;10:5814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 36.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 3. | Wickramasinghe N, Devanarayana NM. Unveiling the intricacies: Insight into gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2025;31:98479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 4. | Rossi P, Isoldi S, Mallardo S, Papoff P, Rossetti D, Dilillo A, Oliva S. Combined multichannel intraluminal impedance and pH monitoring is helpful in managing children with suspected gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2018;50:910-915. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hershcovici T, Fass R. Nonerosive Reflux Disease (NERD) - An Update. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;16:8-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Amarasiri LD, Pathmeswaran A, De Silva AP, Dassanayake AS, Ranasinha CD, De Silva J. Comparison of a composite symptom score assessing both symptom frequency and severity with a score that assesses frequency alone: a preliminary study to develop a practical symptom score to detect gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in a resource-poor setting. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:662-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hillman L, Yadlapati R, Thuluvath AJ, Berendsen MA, Pandolfino JE. A review of medical therapy for proton pump inhibitor nonresponsive gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30:1-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jayawardena R, Byrne NM, Soares MJ, Katulanda P, Hills AP. Validity of a food frequency questionnaire to assess nutritional intake among Sri Lankan adults. Springerplus. 2016;5:162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hagströmer M, Oja P, Sjöström M. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ): a study of concurrent and construct validity. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9:755-762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 972] [Cited by in RCA: 1311] [Article Influence: 69.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16831] [Cited by in RCA: 18492] [Article Influence: 430.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ambartsumyan L, Rodriguez L. Gastrointestinal motility disorders in children. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2014;10:16-26. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Bredenoord AJ, Weusten BL, Timmer R, Conchillo JM, Smout AJ. Addition of esophageal impedance monitoring to pH monitoring increases the yield of symptom association analysis in patients off PPI therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:453-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rutter MD, Rees CJ. Quality in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2014;46:526-528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Trudgill NJ, Sifrim D, Sweis R, Fullard M, Basu K, McCord M, Booth M, Hayman J, Boeckxstaens G, Johnston BT, Ager N, De Caestecker J. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines for oesophageal manometry and oesophageal reflux monitoring. Gut. 2019;68:1731-1750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gyawali CP, Zerbib F, Bhatia S, Cisternas D, Coss-Adame E, Lazarescu A, Pohl D, Yadlapati R, Penagini R, Pandolfino J. Chicago Classification update (V4.0): Technical review on diagnostic criteria for ineffective esophageal motility and absent contractility. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33:e14134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gyawali CP, Kahrilas PJ, Savarino E, Zerbib F, Mion F, Smout AJPM, Vaezi M, Sifrim D, Fox MR, Vela MF, Tutuian R, Tack J, Bredenoord AJ, Pandolfino J, Roman S. Modern diagnosis of GERD: the Lyon Consensus. Gut. 2018;67:1351-1362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1178] [Cited by in RCA: 996] [Article Influence: 124.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sifrim D, Roman S, Savarino E, Bor S, Bredenoord AJ, Castell D, Cicala M, de Bortoli N, Frazzoni M, Gonlachanvit S, Iwakiri K, Kawamura O, Krarup A, Lee YY, Soon Ngiu C, Ndebia E, Patcharatraku T, Pauwels A, Pérez de la Serna J, Ramos R, Remes-Troche JM, Ribolsi M, Sammon A, Simren M, Tack J, Tutuian R, Valdovinos M, Xiao Y, Zerbib F, Gyawali CP. Normal values and regional differences in oesophageal impedance-pH metrics: a consensus analysis of impedance-pH studies from around the world. Gut. 2020;gutjnl-2020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ferdinandis TG, Amarasiri L, De Silva HJ. Use of ambulatory oesophageal pH monitoring to diagnose gastrooesophageal reflux disease. Ceylon Med J. 2007;52:130-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Johnson LF, Demeester TR. Twenty-four-hour pH monitoring of the distal esophagus. A quantitative measure of gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Gastroenterol. 1974;62:325-332. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Rome Foundation. Rome IV Criteria. [cited 24 September 2021]. Available from: https://theromefoundation.org/rome-iv/rome-iv-criteria/. |

| 21. | Lee I, Park S. Diagnosis and treatment of reflux hypersensitivity with gastroesophageal reflux symptoms from a surgical perspective. Foregut Surg. 2022;2:8-16. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 22. | Yamasaki T, Fass R. Reflux Hypersensitivity: A New Functional Esophageal Disorder. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;23:495-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Dent J, Vakil N, Jones R, Bytzer P, Schöning U, Halling K, Junghard O, Lind T. Accuracy of the diagnosis of GORD by questionnaire, physicians and a trial of proton pump inhibitor treatment: the Diamond Study. Gut. 2010;59:714-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 259] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rosen R, Vandenplas Y, Singendonk M, Cabana M, DiLorenzo C, Gottrand F, Gupta S, Langendam M, Staiano A, Thapar N, Tipnis N, Tabbers M. Pediatric Gastroesophageal Reflux Clinical Practice Guidelines: Joint Recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;66:516-554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 610] [Cited by in RCA: 578] [Article Influence: 72.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R; Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900-20; quiz 1943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2368] [Cited by in RCA: 2520] [Article Influence: 126.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 26. | Goh KL. Changing epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease in the Asian-Pacific region: an overview. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19 Suppl 3:S22-S25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Savarino E, Zentilin P, Mastracci L, Dulbecco P, Marabotto E, Gemignani L, Bruzzone L, de Bortoli N, Frigo AC, Fiocca R, Savarino V. Microscopic esophagitis distinguishes patients with non-erosive reflux disease from those with functional heartburn. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:473-482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Poh CH, Gasiorowska A, Navarro-Rodriguez T, Willis MR, Hargadon D, Noelck N, Mohler J, Wendel CS, Fass R. Upper GI tract findings in patients with heartburn in whom proton pump inhibitor treatment failed versus those not receiving antireflux treatment. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:28-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Johansson J, Håkansson HO, Mellblom L, Kempas A, Johansson KE, Granath F, Nyrén O. Prevalence of precancerous and other metaplasia in the distal oesophagus and gastro-oesophageal junction. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:893-902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Rex DK, Cummings OW, Shaw M, Cumings MD, Wong RK, Vasudeva RS, Dunne D, Rahmani EY, Helper DJ. Screening for Barrett's esophagus in colonoscopy patients with and without heartburn. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1670-1677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 360] [Cited by in RCA: 314] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Krugmann J, Neumann H, Vieth M, Armstrong D. What is the role of endoscopy and oesophageal biopsies in the management of GERD? Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;27:373-385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Bhatia SJ, Makharia GK, Abraham P, Bhat N, Kumar A, Reddy DN, Ghoshal UC, Ahuja V, Rao GV, Devadas K, Dutta AK, Jain A, Kedia S, Dama R, Kalapala R, Alvares JF, Dadhich S, Dixit VK, Goenka MK, Goswami BD, Issar SK, Leelakrishnan V, Mallath MK, Mathew P, Mathew P, Nandwani S, Pai CG, Peter L, Prasad AVS, Singh D, Sodhi JS, Sud R, Venkataraman J, Midha V, Bapaye A, Dutta U, Jain AK, Kochhar R, Puri AS, Singh SP, Shimpi L, Sood A, Wadhwa RT. Indian consensus on gastroesophageal reflux disease in adults: A position statement of the Indian Society of Gastroenterology. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2019;38:411-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 33. | Savarino E, Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, Pandolfino JE, Roman S, Gyawali CP; International Working Group for Disorders of Gastrointestinal Motility and Function. Expert consensus document: Advances in the physiological assessment and diagnosis of GERD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:665-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Adlekha S, Chadha T, Krishnan P, Sumangala B. Prevalence of helicobacter pylori infection among patients undergoing upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in a medical college hospital in kerala, India. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2013;3:559-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Gado AS, Ebeid BA, Axon AT. Quality assurance in gastrointestinal endoscopy: An Egyptian experience. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2016;17:153-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Watanabe K, Nagata N, Shimbo T, Nakashima R, Furuhata E, Sakurai T, Akazawa N, Yokoi C, Kobayakawa M, Akiyama J, Mizokami M, Uemura N. Accuracy of endoscopic diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection according to level of endoscopic experience and the effect of training. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 37. | Sontag SJ. Rolling review: gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1993;7:293-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Zhu HM. Study of the influence of hiatus hernia on gastroesophageal reflux. World J Gastroenterol. 1997;3:27-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Mittal RK, Fisher M, McCallum RW, Rochester DF, Dent J, Sluss J. Human lower esophageal sphincter pressure response to increased intra-abdominal pressure. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:G624-G630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Lee YY, McColl KE. Pathophysiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;27:339-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Jobe BA, Richter JE, Hoppo T, Peters JH, Bell R, Dengler WC, DeVault K, Fass R, Gyawali CP, Kahrilas PJ, Lacy BE, Pandolfino JE, Patti MG, Swanstrom LL, Kurian AA, Vela MF, Vaezi M, DeMeester TR. Preoperative diagnostic workup before antireflux surgery: an evidence and experience-based consensus of the Esophageal Diagnostic Advisory Panel. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:586-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Savarino E, Tutuian R, Zentilin P, Dulbecco P, Pohl D, Marabotto E, Parodi A, Sammito G, Gemignani L, Bodini G, Savarino V. Characteristics of reflux episodes and symptom association in patients with erosive esophagitis and nonerosive reflux disease: study using combined impedance-pH off therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1053-1061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Zerbib F, Roman S, Bruley Des Varannes S, Gourcerol G, Coffin B, Ropert A, Lepicard P, Mion F; Groupe Français De Neuro-Gastroentérologie. Normal values of pharyngeal and esophageal 24-hour pH impedance in individuals on and off therapy and interobserver reproducibility. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:366-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Zerbib F, des Varannes SB, Roman S, Pouderoux P, Artigue F, Chaput U, Mion F, Caillol F, Verin E, Bommelaer G, Ducrotté P, Galmiche JP, Sifrim D. Normal values and day-to-day variability of 24-h ambulatory oesophageal impedance-pH monitoring in a Belgian-French cohort of healthy subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:1011-1021. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Sifrim D, Castell D, Dent J, Kahrilas PJ. Gastro-oesophageal reflux monitoring: review and consensus report on detection and definitions of acid, non-acid, and gas reflux. Gut. 2004;53:1024-1031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 620] [Cited by in RCA: 613] [Article Influence: 27.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 46. | Tenca A, Campagnola P, Bravi I, Benini L, Sifrim D, Penagini R. Impedance pH Monitoring: Intra-observer and Inter-observer Agreement and Usefulness of a Rapid Analysis of Symptom Reflux Association. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;20:205-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Neto RML, Herbella FAM, Schlottmann F, Patti MG. Does DeMeester score still define GERD? Dis Esophagus. 2019;32:doy118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Koop AH, Francis DL, DeVault KR. Visual and Automated Computer Analysis Differ Substantially in Detection of Acidic Reflux in Multichannel Intraluminal Impedance-pH Monitoring. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:979-980. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Hemmink GJ, Bredenoord AJ, Aanen MC, Weusten BL, Timmer R, Smout AJ. Computer analysis of 24-h esophageal impedance signals. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:271-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Frazzoni L, Frazzoni M, de Bortoli N, Tolone S, Martinucci I, Fuccio L, Savarino V, Savarino E. Critical appraisal of Rome IV criteria: hypersensitive esophagus does belong to gastroesophageal reflux disease spectrum. Ann Gastroenterol. 2018;31:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Lam SK, Hasan M, Sircus W, Wong J, Ong GB, Prescott RJ. Comparison of maximal acid output and gastrin response to meals in Chinese and Scottish normal and duodenal ulcer subjects. Gut. 1980;21:324-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Ferdinandis TG, Dissanayake AS, de Silva HJ. Chronic alcoholism and esophageal motor activity: a 24-h ambulatory manometry study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:1157-1162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 53. | Savarino V, Marabotto E, Zentilin P, Demarzo MG, Pellegatta G, Frazzoni M, De Bortoli N, Tolone S, Giannini EG, Savarino E. Esophageal reflux hypersensitivity: Non-GERD or still GERD? Dig Liver Dis. 2020;52:1413-1420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Martinez SD, Malagon IB, Garewal HS, Cui H, Fass R. Non-erosive reflux disease (NERD)--acid reflux and symptom patterns. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:537-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 291] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Ozin Y, Dagli U, Kuran S, Sahin B. Manometric findings in patients with isolated distal gastroesophageal reflux. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5461-5464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Ang TL, Fock KM, Ng TM, Teo EK, Chua TS, Tan J. A comparison of the clinical, demographic and psychiatric profiles among patients with erosive and non-erosive reflux disease in a multi-ethnic Asian country. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3558-3561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Hershcovici T, Zimmerman J. Functional heartburn vs. non-erosive reflux disease: similarities and differences. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:1103-1109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Isshi K, Matsuhashi N, Joh T, Higuchi K, Iwakiri K, Kamiya T, Manabe N, Nakada T, Ogawa M, Arihiro S, Haruma K, Nakada K. Clinical features and therapeutic responses to proton pump inhibitor in patients with severe reflux esophagitis: A multicenter prospective observational study. JGH Open. 2021;5:99-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Mizyed I, Fass SS, Fass R. Review article: gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and psychological comorbidity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:351-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |