Published online Jan 16, 2026. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v18.i1.111384

Revised: September 17, 2025

Accepted: December 2, 2025

Published online: January 16, 2026

Processing time: 200 Days and 1.8 Hours

Accurate classification of adverse events (AEs) in gastrointestinal endoscopy is essential for safety monitoring and quality improvement. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) lexicon is widely used, while the classification for AEs in gastrointestinal endoscopy (AGREE) is a recently proposed alternative aiming for broader applicability.

To compare the agreement and correlation between the AGREE and ASGE classification systems using real-world data from a Latin American academic endo

A retrospective analysis of a prospective registry was conducted at a tertiary center in Chile, encompassing all endoscopy-related AEs from 2009 to 2022. Each AE was independently graded using both ASGE and AGREE classification sys

Of 176655 procedures performed, 235 AEs (0.13%) were included. Most events were related to therapeutic pro

The AGREE classification strongly correlates with the ASGE lexicon but excludes more cases as non-AEs and shows slightly lower interobserver agreement. These findings support AGREE as a feasible alternative for AE grading in gastrointestinal endoscopy, particularly in diverse clinical environments.

Core Tip: The adverse events in gastrointestinal endoscopy (AGREE) classification is a recently proposed system for the classification of adverse events (AEs) in gastrointestinal endoscopy. There are scarce data about AEs in Latin American and no study has compared AGREE and American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy classifications in our region. Using our prospective AEs registry, the AGREE classification shows a strong correlation with the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy lexicon, and excludes more cases as non-AEs. Our findings support the AGREE system as a feasible alternative for AEs grading in gastrointestinal endoscopy.

- Citation: Corsi O, Martinez R, Aguirre J, Friedrich I, Galeno V, Jimenez V, Briones P, Díaz LA, Espino A, Vargas JI. Application of a novel adverse event classification scale in a Latin American gastrointestinal endoscopy unit. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2026; 18(1): 111384

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v18/i1/111384.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v18.i1.111384

Gastrointestinal endoscopy is a highly safe procedure however, there are several risks of complications and adverse events (AEs)[1,2]. Currently, the risk of AEs has changed with the development of new techniques and devices, which have expanded the list of indications and the safety of endoscopic procedures. The registry and analysis of AEs are paramount for the prevention, monitoring, and appropriate management of AEs[3-5]. Although standardized record systems are necessary, considering that detecting areas of improvement and changes in protocols afterwards are probably the best prevention strategies, only 60% of endoscopy units worldwide use an AEs registry[6]. Also, trajectory analysis and comparisons are difficult due to the heterogeneity of AE definition and classification applied by each unit[7].

In 2010, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) published expert recommendations for definition, classification, severity of incidents, AEs, and risk factors across the different endoscopic procedures (Table 1). It also categorized them by timing, attribution (i.e., definite, probable, possible, unlikely), and system (i.e., cardiovascular, pulmonary, among others)[8]. Particularly, ASGE defines AEs as “an event that prevents completion of the planned procedure and/or results in admission to hospital, prolongation of existing hospital stay, another procedure (needing sedation/anesthesia), or subsequent medical consultation”, while incidents are “unplanned events that do not interfere with completion of the planned procedure or change the plan of care”.

| ASGE | AGREE | ||

| Grading | Definition | Grading | Definition |

| Mild | Procedure aborted (or not started) because of an adverse event | No adverse event | A telephone contact with the general practitioner, outpatient clinic, or endoscopy service without any intervention |

| Extended observation of the patient after the procedure, < 3 hours, without any intervention | |||

| Postprocedure medical consultation | Grade I | Adverse events with any deviation of the standard postprocedural course, without the need for pharmacologic treatment or endoscopic, radiologic, or surgical interventions | |

| Unplanned hospital admission or prolongation of hospital stay for 3 nights | Presentation at the emergency ward, without any intervention | ||

| Hospital admission (< 24 hours), without any intervention | |||

| Allowed therapeutic regimens are drugs as antiemetics, antipyretics, analgesics, and electrolytes | |||

| Allowed diagnostic tests: Radiology and laboratory tests | |||

| Moderate | Unplanned anesthesia/ventilation support, i.e., endotracheal intubation during conscious sedation | Grade II | Adverse events requiring pharmacologic treatment with drugs other than those allowed for grade I adverse events (i.e., antibiotics, antithrombotics, etc.) |

| Unplanned admission or prolongation for 4-10 nights | |||

| ICU admission for 1 night | Blood or blood product transfusions | ||

| Transfusion | Hospital admission for more than 24 hours | ||

| Repeat endoscopy for an adverse event | Grade III | Adverse events requiring endoscopic, radiologic, or surgical intervention | |

| Interventional radiology for an adverse event | Grade IIIa | Endoscopic or radiologic intervention | |

| Interventional treatment for integument injuries | Grade IIIb | Surgical intervention | |

| Severe | Unplanned admission or prolongation for > 10 nights | Grade IV | Adverse events requiring intensive care unit/critical care unit admission |

| ICU admission > 1 night | Grade IVa | Single-organ dysfunction (including dialysis) | |

| Surgery for an adverse event | Grade IVb | Multiorgan dysfunction | |

| Permanent disability (specify) | |||

| Fatal | Death | Grade V | Death of the patient |

Recently, the classification for AEs in gastrointestinal endoscopy (AGREE) was proposed to evaluate the severity of gastrointestinal endoscopy AEs (Table 1)[6]. It is based on Clavien-Dindo classification for surgical AEs, but some adjustments were necessary to make it suitable for gastrointestinal endoscopy. The AGREE classification was validated in a 3-step process involving international endoscopist experts, and it exhibits a higher interobserver agreement than the ASGE classification in a real-world AEs registry[6,9]. Specifically, AEs are defined as “negative outcome for the patient that prevents completion of a planned procedure or causes any deviation from the standard postprocedural course”, excluding contacts or extended observation without any intervention.

To our knowledge, there are few evaluations of the correlation between both scales globally[9]. In addition, data about gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures AEs are scarce in Latin America. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the corre

This study was designed as a single-center cohort study, drawing upon a meticulously maintained, prospective local handwritten AEs registry. This registry is housed at the Digestive Endoscopy Center within the UC-Christus Health Network, a prominent medical institution located in Santiago, Chile. The scope of the study encompassed all AEs re

The Digestive Endoscopy Center is a comprehensive academic unit that conducts a wide array of endoscopic pro

For inclusion in this study, every AE had to possess complete demographic and clinical data, ensuring the robustness and validity of the analysis. The ethical conduct of the study was paramount. It received comprehensive Institutional Review Board approval from the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, identified by the approval No. 221206001. Furthermore, the study strictly adhered to the principles of Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the ethical tenets outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All authors involved in this research collectively approved the final version of the manuscript and assume full responsibility for the accuracy, integrity, and completeness of the presented data.

In the case of endoscopic mucosal resection or endoscopic submucosal dissection, the endoscopy unit contacts patients one week later to monitor. Moreover, in case of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) all patients assist an outpatient visit after discharge. The prospective local AE registry was used to detect potential AEs and identify procedures and patients. We used the AEs diagnoses assigned by the treating clinicians according to standard clinical practice. Two blinded authors independently reviewed the clinical record, procedure report, and rated each AEs severity according to the ASGE classification system, with discrepancies resolved by a third reviewer[8]. Additionally, two other blinded authors also reviewed the clinical record, procedure report, and classified AEs using the AGREE system, with discrepancies resolved by a third reviewer[6]. All reviewers were trained locally in both ASGE and AGREE systems by an endoscopist expert who did not participate in AEs evaluation or resolution of discrepancies. When several AEs occur after a procedure, only the most severe AEs were graded using both classifications.

Categorical variables were expressed as relative frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables as means, SD, medians, and ranges as specified in the text. Interobserver agreement within each scale was assessed using the Kappa correlation test, and correlation between classification systems was analyzed with Spearman’s rank correlation test. Analyses were performed using RStudio (version 1.3.1056; Posit, Boston, MA, United States).

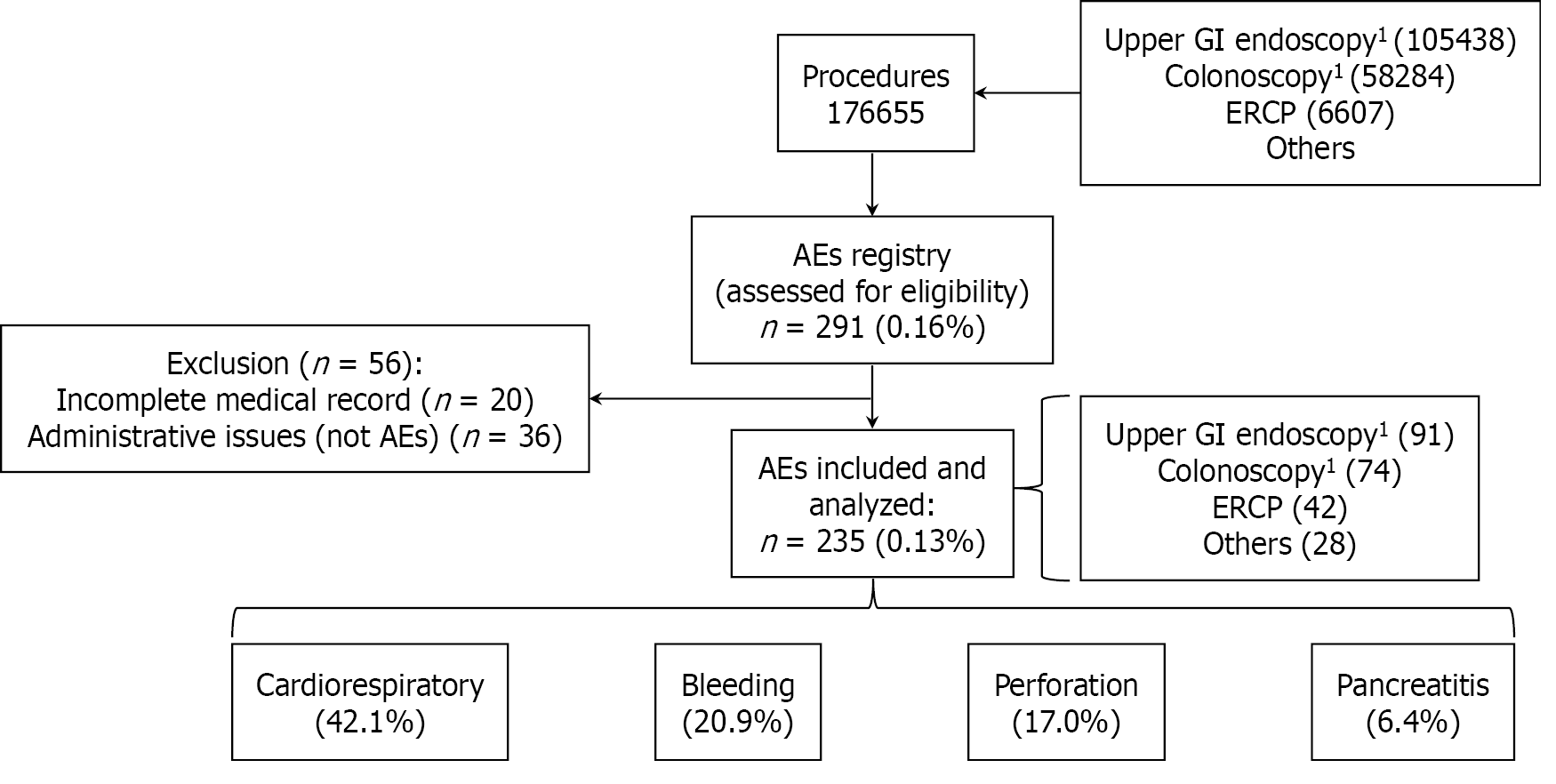

A total of 176655 endoscopic procedures were performed in our unit during the study period, and 291 AEs were registered and reviewed by the authors. However, 20 were excluded because they had incomplete medical records, and 36 were excluded because they corresponded to an administrative issue (not clinical AEs). Finally, 235 AEs from 235 patients were included, corresponding to 0.13% of endoscopic procedures (Figure 1). Among all participants included in this study, 136 (57.9%) were female, and the median age was 63.7 years (interquartile range 52.2-80.0). The most frequent comorbidities identified in those who presented AEs were cardiovascular diseases in 101 patients (43.0%), type 2 diabetes mellitus in 28 patients (11.9%), and respiratory diseases in 21 patients (8.9%). Only 34 patients who suffered an AEs (14.5%) were using antiplatelet or anticoagulant treatment at the moment of the procedure.

Analysis of AEs revealed a clear prevalence of specific types and procedural contexts. Cardiorespiratory events constituted the largest category, accounting for 99 out of 235 (42.1%) AEs. This was followed by bleeding events, which occurred in 49 cases (20.9%), and perforations, observed in 40 instances (17.0%).

The majority of AEs, 121 out of 235 (51.50%), were associated with therapeutic procedures and ERCP was the leading therapeutic procedure associated with AEs, with 42 occurrences (17.87%). Furthermore, the data on fatalities underscores the severity of AEs in therapeutic settings: All but one death occurred as a consequence of AEs encountered during therapeutic procedures. However, diagnostic colonoscopy, excluding therapeutic colonoscopies, was the single leading procedure type linked to AEs, with 47 occurrences (20.0%).

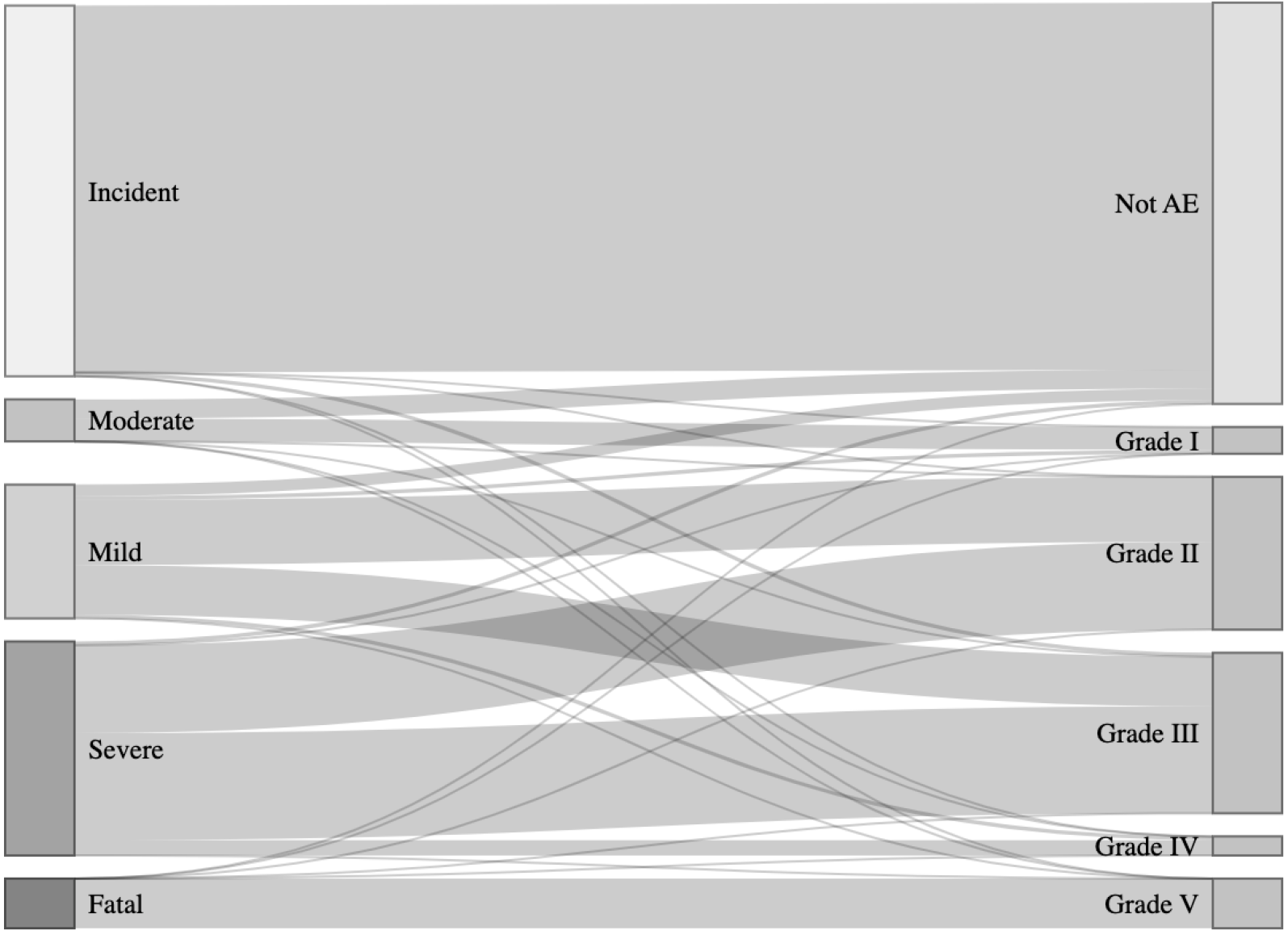

According to the ASGE classification: 42.13% (99/235) events were identified as incidents, 13.62% (32/235) as mild AEs, 14.89% (35/235) as moderate AEs, 23.83% (56/235) as severe AEs, and 5.53% (13/235) were fatal (Figure 2). The interobserver agreement Kappa was 0.83 (95% confidence interval: 0.78-0.87), indicating a great agreement.

Whereas the AGREE system categorized 45.96% (108/235) events as not AEs (mainly desaturation, hypertension, and lack of sedation). The remaining 127 (54%) events were distributed as follows: 3.83% (9/235) as grade I, 23.83% (56/235) as grade II, 18.72% (44/235) as grade III, 2.13% (5/235) as grade IV, and 5.53% (13/235) as fatal (V) (Figure 2). The interobserver agreement Kappa was 0.74 (95% confidence interval: 0.68-0.80), indicating a substantial agreement. The distribution of AGREE categories in both diagnostic and therapeutic procedures is shown in Table 2.

| AGREE categories | Diagnostic procedures (n = 114) | Therapeutic procedures (n = 121) |

| No adverse event | 75 (65.79) | 33 (27.73) |

| Grade I | 6 (5.26) | 3 (2.52) |

| Grade II | 21 (18.42) | 35 (29.41) |

| Grade III | 9 (7.89) | 35 (29.41) |

| Grade IV | 2 (1.75) | 3 (2.52) |

| Grade V | 1 (0.88) | 12 (10.08) |

Cross-system correlation between ASGE classification and AGREE system was evaluated using Spearman’s correlation, yielding a ρ coefficient of 0.89 (P < 0.001), suggesting a very high correlation. In subgroup analysis, ρ was 0.93 (P < 0.001) for diagnostic procedures and 0.81 (P < 0.001) for therapeutic procedures.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first validation of the AGREE classification in a Latin American real-world setting. Our results support the strong correlation between ASGE and AGREE grading, similar to the Italian study findings[6,9]. However, in this cohort, AGREE shows a slightly lower interobserver agreement compared to ASGE lexicon. Potential advantages of the AGREE classification system are the exclusion of events as non-AEs and the use of clearer and more specific terminology. This may explain why ASGE´s moderate and severe categories were redistributed among grades II-IIIa-IIIb-IVa-IVb of the AGREE classification.

The risk of AEs has changed with the development of new techniques and devices, which have expanded the list of indications and safety of endoscopic procedures, but AEs cannot be completely eliminated. In our experience, they were more frequent and severe during therapeutic procedures, but almost half of AEs were associated with diagnostic examination and diagnostic colonoscopy was the leading procedure linked to AEs. It was not surprising because diagnostic procedures are significantly more frequent than therapeutic procedures. So, it is crucial that all endoscopist training curricula include the diagnosis and management of AEs, as recommended by international guidelines[10]. On the other hand, it is essential that every classification system has good performance in both diagnostic and therapeutic procedures.

Regarding AGREE classification, the exclusion of events such as transient desaturation or hypertension may overlook opportunities to implement simple preventive strategies, for example, routine oxygen supplementation during pro

On the other hand, disregarding insufficient sedation events may compromise patient-reported satisfaction. Sedation presents a complex challenge: While minimal sedation in diagnostic procedures may be safer from a cardiorespiratory perspective, it is not necessarily so from the patient’s expectations standpoint. This underscores the need to develop personalized local sedation protocols that balance safety and patient satisfaction[11].

The use of clearer and more specific terminology will contribute to comparisons between procedures and institutions. A potential advantage is that AGREE classification focuses on postprocedural interventions, allowing for broad categories that fit all kinds of potential AEs related to several types of procedures, from diagnostic to therapeutic, including luminal, hepatobiliary, and third-space endoscopy. A comparison between both classification systems is shown in Table 3.

| Feature | ASGE lexicon | AGREE classification |

| Definition | An event that prevents completion of the planned procedure and/or results in admission to hospital, prolongation of existing hospital stay, another procedure (needing sedation/anesthesia), or subsequent medical consultation | A negative outcome for the patient that prevents completion of a planned procedure or causes any deviation from the standard postprocedural course |

| Severity categories | Mild, moderate, severe, fatal | Grades 1 to 5 (based on clinical impact, management, and outcome) |

| Also, it qualifies for all events timing and attribution | ||

| Applicability | All gastrointestinal endoscopy procedures | All gastrointestinal endoscopy procedures |

| Adopted historically | Should enable comparison between GI endoscopy and surgery or interventional radiology | |

| Focus on hospital admission and postprocedural interventions | Focus on postprocedural interventions | |

| Origin | United States and Canada | Worldwide |

Nevertheless, the novel AGREE also raises some concerns, but we believe those do not limit its usefulness[12]. Defining AEs as “a negative outcome for the patient that prevents completion of a planned procedure or causes any deviation from the standard postprocedural course” forces a review against the local standard protocol because “postprocedural course” is influenced by local policies and resources. For example, a significant proportion of post-therapeutic hospital admi

Every endoscopy unit needs robust strategies for AEs. Tracking the incidence of AEs is the first step for evaluating procedure safety, trends changes over time, and improving protocols afterwards; however, it faces several barriers[13]. The reporting of all events “irrespective of the likelihood of a potential link” would require collective effort and may overestimate AEs rate, but is the only way to track all possibly related AEs. However, voluntary AEs reporting rates among community endoscopists are low[14], and only two-thirds of advanced endoscopists reported AEs to their AE database systems[6]. In our opinion, restricting the analysis to clinically significant events will facilitate the implementa

Our study’s main strength is the long period and diversity or procedures covered by our database. We highlight that our endoscopy unit performs a large number and wide range of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, including advanced endoscopic resections and biliopancreatic endoscopy. The categorization by two blinded teams ensures inde

On the other hand, our study has some limitations. Remarkably, our rate of AEs and mortality is lower than the global rate. We believe that two factors could explain this situation. In the first place, it is highly probable that not all AEs were registered because our voluntary and manual AEs recording system requires high commitment and any AE in the preparation phase was registered. It could be especially relevant for severe AEs (for example, pancreatitis after ERCP) as legal consideration might restrain the voluntary registration. On the other hand, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy accounts for more than half of total procedures, where complication rates are significantly lower than colonoscopy or ERCP. Nevertheless, the correlation between both classification systems in our setting is similar to previous experiences[9]. Also, we did not perform a subanalysis according to the type of endoscopic procedures (i.e., upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, colonoscopy, ERCP) because we intended to offer a broad validation rather than concentrating on specific endoscopic techniques. Similarly, we could not perform a subanalysis according to patients’ risk because ASA class information was not available. Finally, temporal changes in complications were not assessed, and future studies could address this aspect to provide insights into the influence of evolving practices on classification system performance.

The implementation of a universal and straightforward classification of AEs is crucial for gastrointestinal practice to detect potential areas of improvement[13]. Both ASGE and the novel AGREE classification systems are good tools for this purpose, but further research in different countries, especially in underrepresented regions, is needed to evaluate the feasibility of implementation.

| 1. | Levy I, Gralnek IM. Complications of diagnostic colonoscopy, upper endoscopy, and enteroscopy. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;30:705-718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Richter JM, Kelsey PB, Campbell EJ. Adverse Event and Complication Management in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:348-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | ASGE Endoscopy Unit Quality Indicator Taskforce, Day LW, Cohen J, Greenwald D, Petersen BT, Schlossberg NS, Vicari JJ, Calderwood AH, Chapman FJ, Cohen LB, Eisen G, Gerstenberger PD, Hambrick RD 3rd, Inadomi JM, MacIntosh D, Sewell JL, Valori R. Quality indicators for gastrointestinal endoscopy units. VideoGIE. 2017;2:119-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Ben-Menachem T, Decker GA, Early DS, Evans J, Fanelli RD, Fisher DA, Fisher L, Fukami N, Hwang JH, Ikenberry SO, Jain R, Jue TL, Khan KM, Krinsky ML, Malpas PM, Maple JT, Sharaf RN, Dominitz JA, Cash BD. Adverse events of upper GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:707-718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 5. | Kaminski MF, Thomas-Gibson S, Bugajski M, Bretthauer M, Rees CJ, Dekker E, Hoff G, Jover R, Suchanek S, Ferlitsch M, Anderson J, Roesch T, Hultcranz R, Racz I, Kuipers EJ, Garborg K, East JE, Rupinski M, Seip B, Bennett C, Senore C, Minozzi S, Bisschops R, Domagk D, Valori R, Spada C, Hassan C, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Rutter MD. Performance measures for lower gastrointestinal endoscopy: a European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) quality improvement initiative. United European Gastroenterol J. 2017;5:309-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nass KJ, Zwager LW, van der Vlugt M, Dekker E, Bossuyt PMM, Ravindran S, Thomas-Gibson S, Fockens P. Novel classification for adverse events in GI endoscopy: the AGREE classification. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;95:1078-1085.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 221] [Article Influence: 55.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kim SY, Kim HS, Park HJ. Adverse events related to colonoscopy: Global trends and future challenges. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:190-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 26.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 8. | Cotton PB, Eisen GM, Aabakken L, Baron TH, Hutter MM, Jacobson BC, Mergener K, Nemcek A Jr, Petersen BT, Petrini JL, Pike IM, Rabeneck L, Romagnuolo J, Vargo JJ. A lexicon for endoscopic adverse events: report of an ASGE workshop. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:446-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1238] [Cited by in RCA: 2022] [Article Influence: 126.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Crispino F, Merola E, Tasini E, Cammà C, di Marco V, de Pretis G, Michielan A. Adverse events in gastrointestinal endoscopy: Validation of the AGREE classification in a real-life 5-year setting. Dig Liver Dis. 2023;55:933-937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Waschke KA, Anderson J, Valori RM, MacIntosh DG, Kolars JC, DiSario JA, Faigel DO, Petersen BT, Cohen J; Chair of 2017-18 ASGE Training Committee. ASGE principles of endoscopic training. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90:27-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sidhu R, Turnbull D, Haboubi H, Leeds JS, Healey C, Hebbar S, Collins P, Jones W, Peerally MF, Brogden S, Neilson LJ, Nayar M, Gath J, Foulkes G, Trudgill NJ, Penman I. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on sedation in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gut. 2024;73:219-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 33.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Facciorusso A, Hassan C, Repici A. The AGREE classification: A useful new tool or just a procrustean bed? Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;95:1280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Moreels TG. How to implement adverse events as a quality indicator in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Dig Endosc. 2024;36:89-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Della Casa FC, Monino L, Deprez PH, Steyaert A, Pendeville P, Piessevaux H, Moreels TG. How to track and register adverse events and incidents related to gastrointestinal endoscopy. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2022;85:499-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/