Published online Jan 16, 2026. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v18.i1.110353

Revised: June 17, 2025

Accepted: November 17, 2025

Published online: January 16, 2026

Processing time: 224 Days and 18.5 Hours

Acute cholangitis (AC) is characterized by infection and inflammation of the biliary tree, often resulting from acute biliary obstruction.

To evaluate outcomes of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and laparoscopic common bile duct exploration (LCBDE) in the man

Between 2016 and 2021, a total of 31817 patients were included, with 30330 (95.3%) undergoing ERCP and 1487 (4.67%) undergoing LCBDE.

ERCP patients were older (mean age 64.5 years vs 59.7 years; P < 0.001) with higher Medicare use (56.1% vs 48.1%) compared to LCBDE patients. LCBDE patients had more elective admissions (19.6% vs 11.7%; P < 0.001) and were treated more often in non-teaching hospitals (P < 0.001). Complication rates differed significantly: LCBDE patients had higher respiratory failure (3.34% vs 2.34%; P = 0.026) and bile duct perforation (1.55% vs 0.64%; P = 0.026), while ERCP patients had higher rates of pancreatitis (P < 0.001) and jaundice (P = 0.002). Late ERCP was associated with higher rates of septic shock (1.23%), respiratory failure (3.80%), and bile duct perforation (0.93%) compared to earlier timing. Patients undergoing late ERCP also had longer hospital stays and higher costs (P < 0.001). LCBDE patients experienced significantly longer hospital stays (mean 8.92 days vs 4.89 days) and higher costs, particularly in late interventions (P < 0.001).

ERCP remains the preferred intervention for AC, with earlier procedures resulting in better outcomes and lower resource utilization. LCBDE, while less common, is associated with longer hospital stays and higher costs, particularly when performed late. Optimizing timing for both ERCP and LCBDE is critical to improving patient out

Core Tip: Timely intervention for biliary issues is crucial, as urgent and early retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) procedures generally lead to shorter hospital stays and lower costs compared to delayed interventions. Patients undergoing late ERCP face increased risks of severe complications like septic shock and respiratory failure, and higher readmission rates. While laparoscopic common bile duct exploration (LCBDE) patients experienced higher rates of certain complications (respiratory failure, bile duct perforation), adjusted analyses showed no significant difference in 30-day readmissions between LCBDE and ERCP, although LCBDE typically incurred longer stays and higher costs. Factors like older age, higher comorbidities, and Medicaid coverage were associated with increased 30-day readmission risk. Ultimately, prompt management of biliary conditions significantly influences patient outcomes, with delays often leading to a higher burden of care.

- Citation: Choday S, Alsheikh J, Vyas N. Timing of intervention: Assessing early vs late endoscopic and surgical interventions in acute cholangitis. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2026; 18(1): 110353

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v18/i1/110353.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v18.i1.110353

Acute cholangitis (AC), also known as ascending cholangitis, is an infection of the biliary tree characterized by fever, jaundice, and abdominal pain, typically resulting from biliary obstruction[1]. Diagnosis relies on clinical presentation, laboratory findings, and imaging studies. Treatment involves intravenous fluid administration, antimicrobial therapy, and timely bile duct drainage. According to the Tokyo guidelines, AC should be suspected in patients presenting with the Charcot triad: (1) Fever; (2) Abdominal pain; and (3) Jaundice. In severe cases, patients may experience confusion and hypotension, referred to as Reynolds' pentad[2]. While the Charcot triad has a low sensitivity (approximately 25%), its specificity exceeds 90%[3]. Initial management focuses on stabilizing critically ill patients through intravenous fluids and antibiotics, followed by urgent biliary drainage. Once the patient is stabilized, relieving the obstruction becomes the priority. This can be achieved via several methods, including surgical, endoscopic, or percutaneous approaches, or a combination technique known as the rendezvous procedure[4]. The choice of intervention depends on the patient’s condition and the available expertise. High-risk patients with organ dysfunction require early and urgent biliary dra

Hospitalization data were obtained from the Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD) spanning the calendar years 2016-2021. The NRD is part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, a collection of databases developed through a partnership with Federal-State-Industry organizations and sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality[6]. This database enables the estimation of nationally representative hospital readmissions across all age groups. The NRD includes approximately 18 million unweighted discharges annually, which corresponds to an estimated 35 million discharges when weighted[6]. In 2021, for example, the NRD comprised data on approximately 17 million discharges, representing an estimated 59.6% of all hospitalizations nationwide. As the NRD does not contain identifiable personal information, this study was classified as not involving human subjects and was therefore exempt from Institutional Review Board approval and no informed consent statement is required.

The analysis included hospitalizations with a primary discharge diagnosis of AC, identified using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision: Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM), in combination with procedure codes for either endoscopic ERCP or LCBDE, as specified in the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision: Procedure Coding System (ICD-10-PCS) (Supplementary Table 1). Patients younger than 18 years of age, missing data on length of stay (LOS), total cost, or in-hospital mortality were excluded. Admissions occurring in January and December were also excluded to ensure the availability of complete 30-day follow-up data within each calendar year.

The primary outcome of this study was the all-cause 30-day readmission rate. Secondary outcomes, evaluated during the index hospitalization, included LOS, total hospitalization cost, and in-hospital mortality. Hospitalization costs were ad

The study utilized patient demographic variables, including age, sex, primary payer status, income quartile, elective admission status, and weekend admission status. Hospital-level characteristics, such as bed size (small, medium, or large) and location/type (urban teaching, urban non-teaching, or rural), were also analyzed. Procedure classification was based on ICD-10-PCS codes to identify patients undergoing ERCP or LCBDE. ERCP patients were categorized into four groups according to the timing of the procedure following admission: (1) ERCP within 24 hours (urgent ERCP); (2) ERCP within 24-48 hours (early ERCP); (3) ERCP more than 48 hours after admission (late ERCP); and (4) No ERCP performed. LCBDE patients were stratified similarly using the same time intervals. Furthermore, ICD-10-CM codes were employed to identify 19 Charlson comorbidities, which were used to calculate the Charlson Comorbidity Index as a predictor of in-hospital mortality[8].

The total unweighted sample size included in the analysis was 31817 patients (Table 1), consisting of 30330 (95.3%) patients undergoing ERCP and 1487 (4.67%) LCBDE. The mean (SE) age of ERCP patients was 64.5 ± 0.097 years, while the mean age of LCBDE patients was 59.7 ± 0.49 years (P < 0.001). The proportion of females was higher among the LCBDE group vs the ERCP group (54.0% vs 51.5%; P < 0.05). No significant differences were observed in income quartile proportions between the two groups. However, significant differences were noted in the primary payer categories (P < 0.001). Medicaid coverage was higher among LCBDE patients (12.5%) vs ERCP patients (9.81%). Similarly, a large proportion of LCBDE patients had private insurance (34.5% vs 28.9%). Conversely, Medicare usage was higher in the ERCP group (56.1%) vs the LCBDE group (48.1%). A greater proportion of LCBDE patients underwent elective admissions compared to ERCP patients (19.6% vs 11.7%; P < 0.001). Additionally, LCBDE procedures were more commonly performed in urban non-teaching and rural hospitals compared to ERCP (P < 0.001).

| Demographics (unweighted n = 31817) | Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography only (n = 30330, 95.3%) | Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration only (n = 1487, 4.67%) | P value1 |

| Age, years (mean, SE) | 64.5 (0.097) | 59.7 (0.49) | < 0.001 |

| Sex, female (%, SE) | 51.5 (0.31) | 54.0 (1.39) | 0.028 |

| Income quartile (%, 95%CI) | 0.24 | ||

| 1 | 25.6 (0.27) | 23.9 (1.20) | |

| 2 | 27.6 (0.28) | 26.7 (1.25) | |

| 3 | 25.8 (0.28) | 26.2 (1.28) | |

| 4 | 20.9 (0.24) | 23.0 (1.15) | |

| Primary payer (%, SE) | < 0.001 | ||

| Medicare | 56.1 (0.31) | 48.1 (1.40) | |

| Medicaid | 9.81 (0.18) | 12.5 (0.92) | |

| Private | 28.9 (0.28) | 34.5 (1.34) | |

| Self-pay | 2.41 (0.098) | 2.82 (0.47) | |

| Other | 2.69 (0.10) | 2.17 (0.42) | |

| Elective admission (%, SE) | 11.7 (0.21) | 19.6 (1.13) | < 0.001 |

| Weekend admission (%, SE) | 19.1 (0.25) | 18.8 (1.11) | 0.83 |

| Hospital location (%, SE) | < 0.001 | ||

| Urban/non-teaching | 14.7 (0.048) | 16.3 (0.96) | |

| Urban/teaching | 82.9 (0.052) | 79.5 (1.05) | |

| Rural | 2.44 (0.024) | 4.19 (0.48) | |

| Hospital bed size (%, SE) | 0.29 | ||

| Small | 10.9 (0.04) | 11.7 (0.82) | |

| Medium | 21.1 (0.06) | 22.3 (1.16) | |

| Large | 68.0 (0.065) | 66.0 (1.29) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (mean, SE) | 3.35 (0.02) | 2.53 (0.086) | < 0.001 |

| Septic shock (%, SE) | 0.57 (0.044) | 0.95 (0.24) | 0.056 |

| Severe sepsis (%, SE) | 0.46 (0.041) | 0.86 (0.28) | 0.054 |

| SIRS with organ failure (%, SE) | 0.064 (0.014) | 0.052 (0.051) | 0.83 |

| SIRS without organ failure (%, SE) | 0.91 (0.056) | 0.76 (0.22) | 0.54 |

| Respiratory failure (%, SE) | 2.34 (0.094) | 3.34 (0.52) | 0.026 |

| Kidney failure (%, SE) | 13.0 (0.20) | 12.2 (0.91) | 0.39 |

| Thrombocytopenia (%, SE) | 3.89 (0.12) | 3.94 (0.53) | 0.92 |

| Altered mental status (%, SE) | 0.19 (0.026) | 0.27 (0.12) | 0.41 |

| Abnormal coagulation (%, SE) | 1.51 (0.079) | 0.83 (0.24) | 0.04 |

| Bile duct perforation (%, SE) | 0.64 (0.05) | 1.55 (0.36) | < 0.001 |

| Post procedural bleeding (%, SE) | 0.36 (0.039) | 0.19 (0.11) | 0.28 |

| Chronic pancreatitis (%, SE) | 5.58 (0.15) | 2.89 (0.50) | < 0.001 |

| Acute pancreatitis (%, SE) | 7.52 (0.16) | 3.12 (0.48) | < 0.001 |

| Abdominal pain (%, SE) | 3.48 (0.12) | 4.45 (0.58) | 0.069 |

| Jaundice (%, SE) | 5.85 (0.14) | 3.75 (0.52) | 0.002 |

| Cholelithiasis | 6.01 (0.15) | 18.1 (1.10) | < 0.001 |

| Choledocholithiasis (%, SE) | 1.89 (0.083) | 1.34 (0.31) | 0.15 |

| Biliary obstruction (%, SE) | 85.1 (0.23) | 53.9 (1.40) | < 0.001 |

| Carcinoma of intrahepatic bile duct (%, SE) | 5.10 (0.14) | 3.59 (0.47) | 0.008 |

| Malignant neoplasm of pancreas (%, SE) | 17.2 (0.23) | 7.45 (0.69) | < 0.001 |

| Inflation-adjusted total cost (mean, SE) | 16968.87 (80.2) | 20011.85 (446.7) | < 0.001 |

| Length of stay (mean, SE) | 4.89 (0.027) | 5.80 (0.14) | < 0.001 |

| In-hospital mortality (%, SE) | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 30-day readmission (%, SE) | 25.6 (0.27) | 21.8 (1.15) | 0.002 |

| 30-day mortality (%, SE) (n = 5354) | 5.27 (0.26) | 2.93 (0.96) | 0.072 |

No significant differences were observed in the incidence of septic shock or severe sepsis between the two groups (P > 0.05). However, LCBDE patients experienced higher incidences of respiratory failure (3.34% vs 2.34%; P = 0.026) and bile duct perforation (1.55% vs 0.64%; P = 0.026). Conversely, the ERCP group had significantly higher proportions of chronic and acute pancreatitis (P < 0.001) and jaundice (P = 0.002). The proportion of 30-day readmissions was significantly higher in the ERCP group at the univariate level compared to the LCBDE group (25.6% vs 21.6%; P < 0.001). However, after adjusting for demographics and hospital characteristics, no significant association between procedure type and 30-day readmission was observed [odds ratio (OR) (95%CI) = 1.06 (0.91-1.23); P = 0.45] (Supplementary Table 2). Ad

After stratifying ERCP status by time from admission, 4.47% (n = 1487) of patients did not undergo ERCP, 18.6% (n = 1487) were classified as urgent ERCP (≤ 24 hours), 53.1% (n = 16645) as early ERCP (24-48 hours), and 23.5% (n = 7380) as late ERCP (> 48 hours) (Table 2). The mean (SE) age was 59.7 ± 0.49 years among patients who did not undergo ERCP, increasing to 65.1 ± 0.19 years in the late ERCP group, thus showing an increasing trend (P < 0.001). Conversely, the highest proportion of females was observed in the no ERCP and urgent ERCP groups (54.6% and 57.6%, respectively), while lower proportions were seen in the early (49.9%) and late ERCP groups (50.4%) (P < 0.001). The late ERCP group had a statistically highest proportion of patients in the lowest income quartile (28.4%) and the lowest proportion in the highest income quartile (19.9%) (Bonferroni P < 0.008). Elective admissions were most common in patients who did not undergo ERCP (19.6%) or underwent urgent ERCP (32.6%), while non-elective admissions predominated in the early and late ERCP groups (P < 0.001).

| Demographics (unweighted n = 31817) | None (n = 1487, 4.74%) | Urgent ERCP (n = 5833, 18.6%) | Early ERCP (n = 16645, 53.1%) | Late ERCP (n = 7380, 23.5%) | P value1 |

| Age, years (mean, SE) | 59.7 (0.49) | 63.4 (0.23)2 | 64.7 (0.13)3,5 | 65.1 (0.19)4,6 | < 0.001 |

| Sex, female (%, SE) | 54.6 (1.39) | 57.6 (0.71) | 49.9 (0.42)3,5 | 50.4 (0.63)4,6 | < 0.001 |

| Income quartile (%, 95%CI) | < 0.001 | ||||

| 1 | 23.9 (1.20) | 24.3 (0.64) | 25.2 (0.37)5 | 28.4 (0.57)4,6,7 | |

| 2 | 26.7 (1.25) | 28.1 (0.67) | 27.5 (0.38) | 26.9 (0.57) | |

| 3 | 26.2 (1.28) | 26.4 (0.65) | 25.8 (0.67) | 24.7 (0.55) | |

| 4 | 23.0 (1.15) | 21.2 (0.56) | 21.4 (0.33) | 19.9 (0.48) | |

| Primary payer (%, SE) | < 0.001 | ||||

| Medicare | 48.1 (1.40) | 55.3 (0.72)2 | 55.3 (0.42)3,5 | 57.9 (0.63)4,6,7 | |

| Medicaid | 12.5 (0.92) | 9.91 (0.39) | 9.78 (0.24) | 11.1 (0.38) | |

| Private | 34.5 (1.34) | 31.1 (0.67) | 29.5 (0.39) | 25.9 (0.56) | |

| Self-pay | 2.82 (0.47) | 2.02 (0.23) | 2.62 (0.14) | 2.36 (0.19) | |

| Other | 2.17 (0.42) | 2.72 (0.23) | 2.79 (0.14) | 2.70 (0.20) | |

| Elective admission (%, SE) | 19.6 (1.13) | 32.6 (0.69)2 | 6.51 (0.23)3,5 | 5.86 (0.31)4,6 | < 0.001 |

| Weekend admission (%, SE) | 18.8 (1.11) | 12.9 (0.50)2 | 20.4 (0.34) | 21.3 (0.52)6 | < 0.001 |

| Hospital location (%, SE) | < 0.001 | ||||

| Urban/non-teaching | 16.3 (0.96) | 12.5 (0.38)2 | 15.8 (0.19)3,5 | 13.9 (0.36)4,7 | |

| Urban/teaching | 79.5 (1.05) | 85.2 (0.42) | 81.8 (0.20) | 83.6 (0.39) | |

| Rural | 4.19 (0.48) | 2.27 (0.19) | 2.47 (0.089) | 2.39 (0.17) | |

| Hospital bed size (%, SE) | < 0.001 | ||||

| Small | 11.7 (0.82) | 9.31 (0.35)2 | 11.3 (0.17) | 9.72 (0.32)7 | |

| Medium | 22.3 (1.16) | 19.0 (0.51) | 21.7 (0.23) | 20.9 (0.46) | |

| Large | 66.0 (1.29) | 71.6 (0.57) | 67.1 (0.27) | 69.3 (0.51) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (mean, SE) | 2.53 (0.086) | 2.65 (0.043)2 | 3.33 (0.027)3,5 | 4.02 (0.045)4,6,7 | < 0.001 |

| Septic shock (%, SE) | 0.95 (0.24) | 0.36 (0.077) | 0.36 (0.047)3 | 1.23 (0.13)6,7 | < 0.001 |

| Severe sepsis (%, SE) | 0.86 (0.28) | 0.41 (0.10) | 0.28 (0.039)3 | 0.93 (0.12)6,7 | < 0.001 |

| SIRS with organ failure (%, SE) | 8 | 8 | 8 | 0.17 (0.049) | 8 |

| SIRS without organ failure (%, SE) | 0.76 (0.22) | 0.81 (0.11) | 0.90 (0.077) | 1.06 (0.13)6 | 0.43 |

| Respiratory failure (%, SE) | 3.35 (0.52) | 2.00 (0.21)2 | 1.82 (0.11)3,5 | 3.80 (0.24)6,7 | < 0.001 |

| Kidney failure (%, SE) | 12.2 (0.91) | 8.07 (0.37)2 | 11.9 (0.27) | 19.2 (0.48)4,6,7 | < 0.001 |

| Thrombocytopenia (%, SE) | 3.94 (0.53) | 2.83 (0.24) | 3.84 (0.16) | 4.75 (0.26)6,7 | < 0.001 |

| Altered mental status (%, SE) | 8 | 8 | 0.17 (0.031) | 0.32 (0.07) | 0.049 |

| Abnormal coagulation (%, SE) | 0.84 (0.24) | 0.73 (0.12) | 1.33 (0.098) | 2.50 (0.19)4,6,7 | < 0.001 |

| Bile duct perforation (%, SE) | 1.55 (0.36) | 0.66 (0.11) 2 | 0.52 (0.062)3,5 | 0.93 (0.13)7 | < 0.001 |

| Post procedural bleeding (%, SE) | 8 | 0.37 (0.088) | 0.28 (0.048) | 0.56 (0.094)7 | 0.004 |

| Chronic pancreatitis (%, SE) | 2.89 (0.50) | 7.64 (0.42)2 | 4.56 (0.18)5 | 6.19 (0.32)4,6,7 | < 0.001 |

| Acute pancreatitis (%, SE) | 3.12 (0.48) | 7.72 (0.37)2 | 7.07 (0.21)3 | 8.43 (0.34)4,7 | < 0.001 |

| Abdominal pain (%, SE) | 4.45 (0.58) | 4.13 (0.29) | 3.23 (0.15) | 3.62 (0.24) | 0.008 |

| Jaundice (%, SE) | 3.76 (0.52) | 3.81 (0.25) | 6.17 (0.19)3,5 | 7.01 (0.32)4,6 | < 0.001 |

| Cholelithiasis (%, SE) | 18.1 (1.10) | 4.83 (0.29)2 | 5.54 (0.19)3,5 | 7.79 (0.34)4,6,7 | < 0.001 |

| Choledocholithiasis (%, SE) | 1.34 (0.31) | 1.89 (0.19) | 1.62 (0.10) | 2.38 (0.19)7 | 0.001 |

| Biliary obstruction (%, SE) | 53.9 (1.41) | 82.2 (0.52)2 | 85.7 (0.29)3,5 | 86.4 (0.44)4,6 | < 0.001 |

| Carcinoma of intrahepatic bile duct (%, SE) | 3.58 (0.47) | 4.36 (0.31) | 4.92 (0.18) | 5.71 (0.30)4,6 | 0.001 |

| Malignant neoplasm of pancreas (%, SE) | 7.45 (0.69) | 14.4 (0.49)2 | 18.5 (0.33)3,5 | 17.1 (0.46)4,6 | < 0.001 |

Significant differences in hospital location were noted among ERCP timing categories, except for the urgent and late ERCP groups. A larger proportion of no ERCP cases were treated in urban non-teaching hospitals compared to urgent ERCP cases (16.3% vs 12.5%; Bonferroni P = 0.008). Patients undergoing urgent or early ERCP were more likely to receive care in urban teaching hospitals (Bonferroni P = 0.008). The mean comorbidity index showed an increasing trend from 2.53 ± 0.086 in the no ERCP group to 4.02 ± 0.045 in the late ERCP group (P < 0.001). With respect to complications, the late ERCP group exhibited the highest incidences of septic shock (1.23%) and severe sepsis (0.93%), with no significant differences compared to the no ERCP group. However, significant differences were noted when compared to the urgent and early ERCP groups (Bonferroni P = 0.008). Respiratory failure was most frequent in the late ERCP group (3.80%), with lower incidences in the urgent (2.00%) and early ERCP groups (1.82%; Bonferroni P < 0.008), while no significant difference was found between the no ERCP and late ERCP groups. Among patients undergoing ERCP, the highest incidence of bile duct perforation occurred in the late ERCP group (0.93%), with a significant difference observed only when compared to the early ERCP group (Bonferroni P = 0.008). The highest incidences of jaundice were observed in the early and late ERCP groups (6.17% and 7.01%, respectively), which were significantly higher compared to the no ERCP and urgent ERCP groups (Bonferroni P = 0.008).

Within the population, 22.0% (n = 7004) were readmitted within 30 days from the index hospitalization (Table 3). The readmitted patients were older (63.9 ± 0.19 vs 54.5 ± 0.11; P < 0.001) and showed lower percentage of females (47.9% vs 52.6%; P < 0.001). Additionally, statistical differences were observed in relation to income quartiles. A larger percentage of readmitted patients were Medicaid patients (11.1% vs 9.62%; P = 0.008). In addition, the proportion of Medicare patients or private insurance patients did not observe noticeable difference between the groups. The main discrepancy in in

| Demographics (unweighted n = 31811) | No 30-day readmission (n = 24807, 77.9%) | 30-day readmission (n = 7004, 22.0%) | P value1 |

| Age, years (mean, SE) | 54.5 (0.11) | 63.9 (0.19) | 0.032 |

| Sex, female (%, SE) | 52.6 (0.35) | 47.9 (0.65) | < 0.001 |

| Income quartile (%, 95%CI) | < 0.001 | ||

| 1 | 25.6 (0.30) | 25.1 (0.58) | |

| 2 | 28.0 (0.32) | 25.9 (0.58) | |

| 3 | 25.7 (0.31) | 26.5 (0.59) | |

| 4 | 20.6 (0.26) | 22.6 (0.52) | |

| Primary payer (%, SE) | 0.008 | ||

| Medicare | 55.9 (0.35) | 54.9 (0.65) | |

| Medicaid | 9.62 (0.19) | 11.1 (0.39) | |

| Private | 29.2 (0.31) | 29.4 (0.59) | |

| Self-pay | 2.50 (0.11) | 2.18 (0.19) | |

| Other | 27.5 (0.11) | 2.41 (0.20) | |

| Elective admission (%, SE) | 13.0 (0.25) | 8.96 (0.39) | < 0.001 |

| Weekend admission (%, SE) | 19.2 (0.27) | 18.7 (0.52) | 0.41 |

| Hospital location (%, SE) | < 0.001 | ||

| Urban/non-teaching | 14.9 (0.10) | 14.0 (0.37) | |

| Urban/teaching | 82.4 (0.11) | 84.0 (0.40) | |

| Rural | 2.67 (0.045) | 1.95 (0.16) | |

| Hospital bed size (%, SE) | 0.52 | ||

| Small | 10.9 (0.097) | 10.7 (0.35) | |

| Medium | 21.3 (0.13) | 20.7 (0.48) | |

| Large | 67.8 (0.15) | 68.6 (0.55) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (mean, SE) | 3.11 (0.022) | 4.07 (0.044) | < 0.001 |

| Septic shock (%, SE) | 0.54 (0.048) | 0.76 (0.10) | 0.038 |

| Severe sepsis (%, SE) | 0.48 (0.046) | 0.47 (0.091) | 0.92 |

| SIRS with organ failure (%, SE) | 0.075 (0.017) | 0.021 (0.015) | 0.071 |

| SIRS without organ failure (%, SE) | 0.93 (0.063) | 0.79 (0.11) | 0.27 |

| Respiratory failure (%, SE) | 2.32 (0.11) | 2.63 (0.21) | 0.17 |

| Kidney failure (%, SE) | 12.7 (0.23) | 13.9 (0.45) | 0.024 |

| Thrombocytopenia (%, SE) | 3.72 (0.13) | 4.51 (0.27) | 0.006 |

| Altered mental status (%, SE) | 0.21 (0.028) | 0.15 (0.051) | 0.40 |

| Abnormal coagulation (%, SE) | 1.38 (0.082) | 1.87 (0.19) | 0.011 |

| Bile duct perforation (%, SE) | 0.73 (0.061) | 0.51 (0.089) | 0.054 |

| Post procedural bleeding (%, SE) | 0.37 (0.042) | 0.32 (0.080) | 0.62 |

| Chronic pancreatitis (%, SE) | 5.52 (0.17) | 5.25 (0.32) | 0.43 |

| Acute pancreatitis (%, SE) | 7.17 (0.17) | 7.85 (0.34) | 0.069 |

| Abdominal pain (%, SE) | 3.34 (0.13) | 3.09 (0.22) | 0.039 |

| Jaundice (%, SE) | 5.76 (0.16) | 5.67 (0.29) | 0.77 |

| Cholelithiasis | 6.75 (0.17) | 5.87 (0.32) | 0.019 |

| Choledocholithiasis (%, SE) | 2.03 (0.095) | 1.28 (0.14) | < 0.001 |

| Biliary obstruction (%, SE) | 82.6 (0.26) | 87.7 (0.45) | < 0.001 |

| Carcinoma of intrahepatic bile duct (%, SE) | 4.59 (0.15) | 6.68 (0.34) | < 0.001 |

| Malignant neoplasm of pancreas (%, SE) | 16.5 (0.25) | 17.9 (0.49) | < 0.001 |

| Inflation-adjusted total cost (mean, SE) | 16526.26 (83.9) | 19234.87 (210.8) | < 0.001 |

| Length of stay (mean, SE) | 4.73 (0.029) | 5.67 (0.067) | < 0.001 |

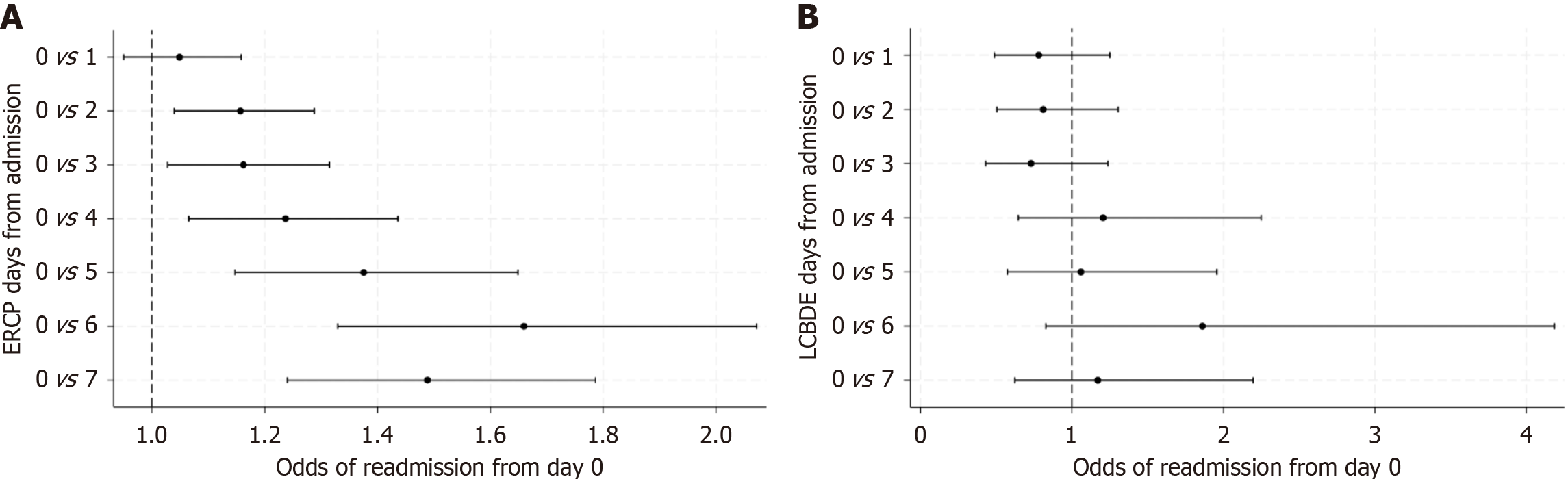

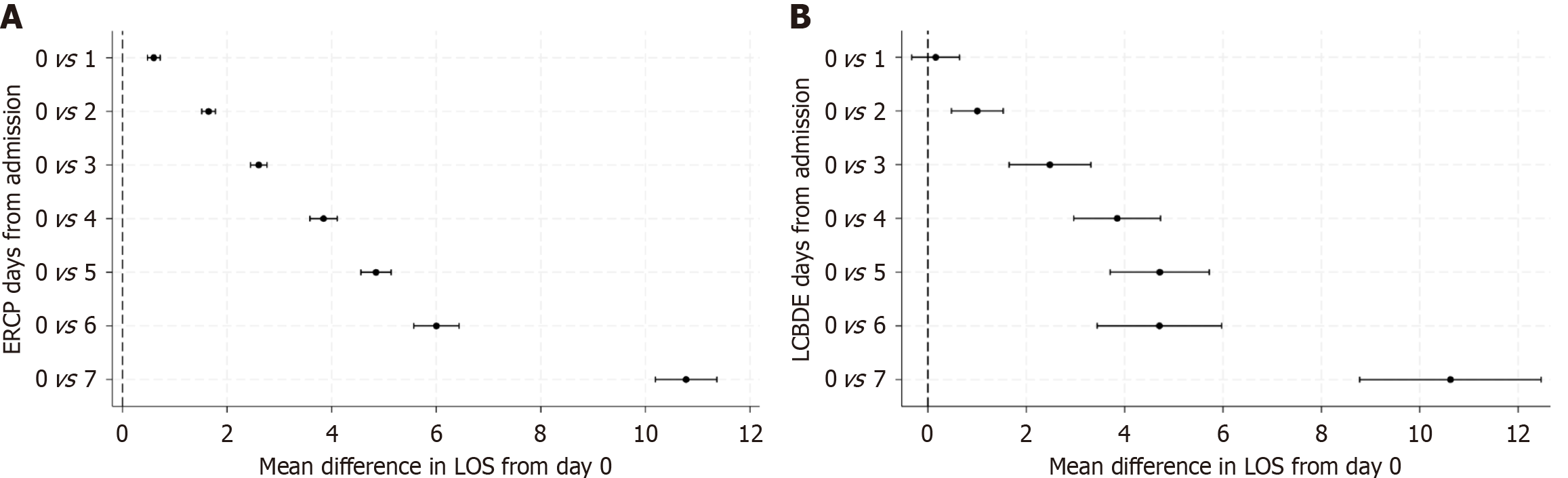

Patients who did not receive ERCP reported 19.9% 30-day readmission (Table 4 and Figure 1). The percentage of readmitted patients steadily increased as the time of ERCP increased. Late ERCP recipients observed a 25.2% readmission rate. However, after adjusting for confounding, the odds of readmission among late ERCP recipients were merely 8% higher compared to the no ERCP group [OR (95%CI) = 1.08 (0.92-1.26); P = 0.36]. When using the urgent ERCP group as the reference, no statistical association was reported among the early ERCP group. However, the odds of readmission among late ERCP recipients were 28% higher compared to the urgent ERCP group [OR (95%CI) = 1.28 (1.15-1.41); P < 0.001]. With respect to secondary outcomes, urgent and early ERCP patients reported decreases in LOS compared to the no ERCP group (P < 0.001), while the late ERCP group observed a longer LOS. Additionally, the early and late ERCP groups showed a longer LOS compared to the urgent group (P < 0.001; Figure 2). Similar trends are seen with total cost. Urgent and early ERCP observed lower costs compared to no ERCP group (P < 0.001), but early ERCP and late ERCP patients showed higher costs when compared to the urgent ERCP group.

| Unweighted (n = 67738) | 30-day readmission1 [% (SE)] | No ERCP as the reference group [odds ratio (95%CI)] | P value | Urgent ERCP as the reference group | P value |

| ERCP | |||||

| None (n = 1487) | 19.9 (1.11) | Reference | |||

| Urgent ERCP (n = 5833) | 17.9 (0.54) | 0.85 (072-0.99) | 0.046 | Reference | |

| Early ERCP (n = 16645) | 21.3 (0.35) | 0.91 (0.78-1.06) | 0.24 | 1.08 (0.99-1.18) | 0.079 |

| Late ERCP (n = 7380) | 25.2 (0.54) | 1.08 (0.92-1.26) | 0.36 | 1.28 (1.15-1.41) | < 0.001 |

| Unweighted (n = 7004) | 30-day mortality1 | ||||

| ERCP | |||||

| None (n = 302) | 2.93 (0.96) | Reference | |||

| Urgent ERCP (n = 1118) | 3.76 (0.58) | 1.24 (0.58-2.65) | 0.58 | Reference | |

| Early ERCP (n = 3586) | 5.36 (0.36) | 1.76 (0.85-3.59) | 0.12 | 1.43 (0.99-2.05) | 0.055 |

| Late ERCP (n = 1896) | 5.95 (0.54) | 1.79 (0.87-3.69) | 012 | 1.46 (0.97-2.15) | 0.066 |

| Length of stay1 [mean (SE)] | β (95%CI) | β (95%CI) | |||

| ERCP | |||||

| None (n = 1487) | 5.81 (0.14) | Reference | |||

| Urgent ERCP (n = 5833) | 2.98 (0.043) | -2.70 (-2.98 to -2.42) | < 0.001 | Reference | |

| Early ERCP (n = 16645) | 4.20 (0.029) | -1.61 (-1.89 to -1.33) | < 0.001 | 1.12 (1.02-1.23) | < 0.001 |

| Late ERCP (n = 7380) | 8.17 (0.073) | 1.82 (1.52-2.14) | < 0.001 | 4.58 (4.42-4.73) | < 0.001 |

| Inflation-adjusted total cost2 [mean (SE)] | β (95%CI) | β (95%CI) | |||

| ERCP | |||||

| None (n = 1487) | 20011.85 (446.7) | Reference | |||

| Urgent ERCP (n = 5833) | 14024.95 (137.8) | -5433.6 (-6316.1 to -4551.0) | < 0.001 | Reference | |

| Early ERCP (n = 16645) | 15164.99 (86.6) | -4826.5 (-5700.7 to -3952.2) | < 0.001 | 599.3 (263.8-934.7) | < 0.001 |

| Late ERCP (n = 7380) | 23509.59 (231.7) | 1951.6 (972.5-2930.7) | < 0.001 | 7391.9 (6902.2-7881.7) | < 0.001 |

As an exploratory analysis, LCBDE timing was stratified using the same definitions as ERCP timing. Stratification showed 95.4% (n = 30330) of patients underwent no LCBDE, 1.22% (n = 389) had urgent LCBDE, 1.83% (n = 583) had early LCBDE, and 1.57% (n = 500) had late LCBDE (Supplementary Table 3). The largest mean age is seen within the no LCBDE group (64.6 ± 0.097 years), thus statistical differences in age were seen between urgent, early, and late LCBDE time categories compared to the no LCBDE group (Bonferroni P < 0.008). No statistical differences were observed in sex and income quartiles. However, statistical differences were observed with respect to insurance status, with differences observed between the urgent and early, LCBDE groups vs the no LCBDE group (Bonferroni P < 0.008).

Charlson comorbidity index showed the largest means within the no LCBDE and the late LCBDE groups (3.35 ± 0.02 and 3.12 ± 0.17, respectively), which results in statistical differences between all the LCBDE timing categories (Bonferroni P < 0.008) except for the no LCBDE and late LCBDE comparison. Among the complications, the percentage of respiratory failures were statistically different between the no LCBDE and the late LCBDE groups (2.34% vs 5.30%) (Bonferroni P < 0.008). Additionally, differences in kidney failure were statistically different between the urgent LCBDE group with the no LCBDE and late LCBDE categories. The proportion of biliary obstruction was the largest within the no LCBDE group (85.2%), while the biliary obstruction percentage ranged from 51% to 56% among the urgent, early, and late LCBDE cate

Mean (SE) LOS among no LCBDE patients was 4.89 ± 0.027 days vs 8.92 ± 0.32 days among the late LCBDE patients. Adjusted linear regression showed late LCBDE patients observed longer LOSs compared to no LCBDE patients [β (95%CI) = 3.65 (3.07-4.23); P < 0.001]. Furthermore, when using urgent ERCP as the reference group, the mean difference in LOS increased to 4.65 days longer compared to the urgent ERCP group [β (95%CI) = 4.56 (3.91-5.21); P < 0.001]. Linear regression also showed larger differences in total cost among the late LCBDE patients (P < 0.001). No statistical associations were observed between LCBDE timing and 30-day readmission or 30-day mortality.

This study provides a comprehensive evaluation of ERCP and LCBDE in managing AC. This study analyzed a large dataset of 31817 patients undergoing ERCP or LCBDE to understand differences in demographics, procedural characteristics, and outcomes. Significant distinctions emerged between the two groups, offering insights into clinical and resource management considerations. ERCP patients were generally older than LCBDE patients, with a mean age difference of approximately five years, consistent with the fact that ERCP is more often utilized in older populations. Female predominance was higher in the LCBDE group, although the difference was modest. The patient demographics and healthcare accessibility differed significantly between the two groups. From previous studies, LCBDE patients were younger on average (59.7 years vs 64.5 years for ERCP) and more likely to have elective admissions (19.6% vs 11.7%)[6,9]. These differences suggest that LCBDE is often utilized in controlled, non-emergent scenarios, whereas ERCP is frequently employed in urgent or emergent settings[10,11].

From previous studies, ERCP was the predominant intervention, utilized in 95.3% of cases, and demonstrated significant advantages in terms of shorter hospital stays (mean 4.89 days vs 5.80 days for LCBDE) and lower inflation-adjusted costs ($16968 vs $20011)[12,13]. These findings demonstrate ERCP’s role as the first-line intervention for biliary decompression due to its minimally invasive nature and cost efficiency. However, ERCP was associated with higher incidences of post-procedural pancreatitis, both acute (7.52% vs 3.12%) and chronic (5.58% vs 2.89%), emphasizing the need for careful patient monitoring[14,15].

LCBDE, while only utilized in only 4.67% of cases, retained importance in specific contexts, such as when ERCP was contraindicated or unsuccessful. LCBDE was particularly effective in cases involving large or impacted stones, where endoscopic methods were less likely to succeed. Despite being associated with higher risks of respiratory failure (3.34% vs 2.34%) and bile duct perforation (1.55% vs 0.64%), LCBDE’s ability to address complex anatomical challenges ensures its continued relevance[16]. Notably, LCBDE was more commonly performed in non-teaching and rural hospitals, reflecting its utility in settings where advanced endoscopic expertise may be unavailable, consistent with other studies[17,18].

Economic considerations also play a pivotal role in intervention selection. While ERCP’s lower costs and shorter hospital stay make it the preferred option in most cases, LCBDE’s cost-effectiveness in managing large or impacted stones should not be overlooked. However, delayed LCBDE interventions significantly increased resource utilization, with longer hospital stays (mean 8.92 days) and higher costs ($23512) compared to early LCBDE[13,19]. LCBDE was associated with longer hospital stays and higher costs compared to ERCP. While early ERCP reduced both cost and LOS, late ERCP and LCBDE showed significant resource utilization.

Despite its less frequent utilization, LCBDE remains a critical option, particularly for patients who cannot undergo ERCP due to complex anatomy or other contraindications. For example, previous studies have demonstrated that LCBDE can achieve comparable long-term outcomes to ERCP when performed by experienced surgeons[20].

The timing of interventions emerged as a crucial determinant of outcomes for both ERCP and LCBDE[13]. Early ERCP (within 24-48 hours) demonstrated superior outcomes, including shorter hospital stays (meaning 4.20 days vs 8.17 days for late ERCP) and reduced hospitalization costs ($15164 vs $23509). Complications such as septic shock (0.36% vs 1.23%) and respiratory failure (1.82% vs 3.80%) were significantly lower in the early intervention group. Patients undergoing early ERCP also had slightly lower rates of other complications, including severe sepsis and renal failure compared to those receiving late ERCP. These findings align with the Tokyo Guidelines 2018’s emphasis on prompt biliary drainage to mitigate systemic inflammation and prevent organ dysfunction[15]. Delayed ERCP was linked with higher incidences of severe sepsis, respiratory failure, and bile duct perforation.

Further stratification of ERCP timing revealed incremental benefits associated with urgent interventions (≤ 24 hours). Compared to early ERCP, urgent ERCP showed additional reductions in procedural complexity, as evidenced by decreased rates of bile duct perforation and biliary strictures, with hospital stays averaging 3.74 days in the urgent group vs 4.20 days in the early group. This highlights the compounded benefits of addressing biliary obstruction promptly, even within the first 24 hours of presentation[21].

For LCBDE, early interventions (≤ 48 hours) also demonstrated better outcomes compared to late procedures. Early LCBDE reduced hospital stays (mean 5.67 days vs 8.92 days) and costs ($16834 vs $23512). It also minimized complications such as respiratory failure, postoperative infections and wound dehiscence[11]. Late LCBDE was linked to increased morbidity, with other studies indicating higher incidences of intra-abdominal abscess formation and prolonged ileus as well[11,18]. These findings show the risks of delayed decompression in severe cases of AC. This reinforces the importance of timely surgical management, particularly in patients with large or impacted stones that exacerbate biliary obstruction. LCBDE procedures were predominantly elective, with higher frequencies in rural and urban non-teaching hospitals.

The influence of patient comorbidities on the timing and outcomes of interventions was also notable. Patients with higher Charlson Comorbidity Index scores were disproportionately represented in late intervention groups, reflecting the challenges of managing acutely ill, high-risk populations[13,16]. These findings revealed the need for tailored man

The role of socioeconomic factors further highlighted disparities in access to timely care. Patients from lower income quartiles and those covered by Medicaid were overrepresented in late intervention groups. This suggests systemic barriers to accessing early procedures. Rural hospitals also reported longer wait times for biliary drainage due to limited access to advanced endoscopic or surgical expertise[20]. These disparities illustrate the importance of health policy reforms aimed at improving equity in care delivery.

The analysis of 30-day readmissions provided valuable insights into the downstream effects of intervention timing on patient outcomes. Among ERCP patients, delayed procedures (> 48 hours) were associated with significantly higher readmission rates (25.2%) compared to urgent (≤ 24 hours) and early (24-48 hours) interventions, which demonstrated readmission rates of 17.9% and 20.1%, respectively. This trend was supported by adjusted analyses, which indicated 28% increased odds of readmission for late ERCP compared to urgent interventions. These findings highlight the com

For LCBDE, overall, 30-day readmission rates were slightly lower than ERCP. However, the timing of intervention still played a critical role. Early LCBDE (≤ 48 hours) was associated with reduced readmission rates compared to late LCBDE, aligning with patterns observed in endoscopic procedures. Socioeconomic disparities further influenced readmission outcomes, with Medicaid recipients and patients from lower income quartiles disproportionately represented in late intervention groups. These findings suggest that systemic barriers to timely surgical intervention contribute to pre

The ERCP group had higher incidences of pancreatitis and jaundice, likely reflective of the primary indications for the procedure. Conversely, LCBDE patients showed a higher frequency of respiratory failure and bile duct perforation. Notably, the incidence of septic shock and severe sepsis did not differ significantly between the groups, suggesting comparable risks in managing critical infections. Although 30-day readmissions were initially higher in the ERCP group, adjusted analyses revealed no significant differences after accounting for demographics and hospital characteristics. The higher readmission odds in late ERCP compared to urgent ERCP underline the importance of early intervention.

Future research should explore predictive analytics to improve intervention timing, particularly for high-risk patients. Comparative studies on cost-effectiveness across healthcare settings would further inform policy decisions and resource allocation. By addressing these systemic challenges, healthcare providers can significantly enhance the quality and equity of care for AC. This will ultimately improve patient outcomes and reduce the overall burden of disease.

This study offers several strengths that contribute to its value in understanding the management of AC. First, the use of a large, nationally representative database allows for comprehensive insights into procedural outcomes across diverse healthcare settings. Second, the stratification of interventions by timing provides critical evidence to guide clinical decision-making, emphasizing the importance of prompt biliary drainage. Additionally, the inclusion of both ERCP and LCBDE ensures that the findings are relevant to a wide range of clinical scenarios, including resource-limited envir

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. The retrospective design of the study may introduce selection bias and limit the ability to establish causality between intervention timing and outcomes. Moreover, reliance on administrative data may result in inaccuracies due to coding errors or unmeasured confounders. For instance, the study could not account for certain clinical variables, such as exact stone size or specific anatomic variations, which may influence procedural success rates and complication risks.

This study demonstrates the critical importance of optimizing procedural timing and addressing systemic disparities to improve AC outcomes and reduce healthcare expenditures. ERCP remains the preferred intervention for its minimally invasive approach and cost-effectiveness. However, LCBDE serves as a vital alternative in resource-limited or non-tertiary settings, particularly for patients with contraindications to endoscopy or complex biliary anatomy.

| 1. | An Z, Braseth AL, Sahar N. Acute Cholangitis: Causes, Diagnosis, and Management. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2021;50:403-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Yokoe M, Hata J, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Asbun HJ, Wakabayashi G, Kozaka K, Endo I, Deziel DJ, Miura F, Okamoto K, Hwang TL, Huang WS, Ker CG, Chen MF, Han HS, Yoon YS, Choi IS, Yoon DS, Noguchi Y, Shikata S, Ukai T, Higuchi R, Gabata T, Mori Y, Iwashita Y, Hibi T, Jagannath P, Jonas E, Liau KH, Dervenis C, Gouma DJ, Cherqui D, Belli G, Garden OJ, Giménez ME, de Santibañes E, Suzuki K, Umezawa A, Supe AN, Pitt HA, Singh H, Chan ACW, Lau WY, Teoh AYB, Honda G, Sugioka A, Asai K, Gomi H, Itoi T, Kiriyama S, Yoshida M, Mayumi T, Matsumura N, Tokumura H, Kitano S, Hirata K, Inui K, Sumiyama Y, Yamamoto M. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: diagnostic criteria and severity grading of acute cholecystitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018;25:41-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 769] [Cited by in RCA: 782] [Article Influence: 97.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sulzer JK, Ocuin LM. Cholangitis: Causes, Diagnosis, and Management. Surg Clin North Am. 2019;99:175-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Smith SE. Management of Acute Cholangitis and Choledocholithiasis. Surg Clin North Am. 2024;104:1175-1189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ramchandani M, Pal P, Reddy DN. Endoscopic management of acute cholangitis as a result of common bile duct stones. Dig Endosc. 2017;29 Suppl 2:78-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Overview of the Nationwide Readmissions Database. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. 2022. Available from: https://www.ahrq.gov/data/hcup/index.html. |

| 7. | United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. CPI inflation calculator. 2022. Available from: https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm. |

| 8. | Glasheen WP, Cordier T, Gumpina R, Haugh G, Davis J, Renda A. Charlson Comorbidity Index: ICD-9 Update and ICD-10 Translation. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2019;12:188-197. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Data use agreement for the nationwide databases from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). 2022. Available from: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/team/NationwideDUA.jsp. |

| 10. | Kwak N, Yeoun D, Arroyo-Mercado F, Mubarak G, Cheung D, Vignesh S. Outcomes and risk factors for ERCP-related complications in a predominantly black urban population. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2020;7:e000462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Buxbaum JL, Abbas Fehmi SM, Sultan S, Fishman DS, Qumseya BJ, Cortessis VK, Schilperoort H, Kysh L, Matsuoka L, Yachimski P, Agrawal D, Gurudu SR, Jamil LH, Jue TL, Khashab MA, Law JK, Lee JK, Naveed M, Sawhney MS, Thosani N, Yang J, Wani SB. ASGE guideline on the role of endoscopy in the evaluation and management of choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;89:1075-1105.e15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 391] [Cited by in RCA: 389] [Article Influence: 55.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Szary NM, Al-Kawas FH. Complications of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: how to avoid and manage them. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2013;9:496-504. [PubMed] |

| 13. | May E, Brown KO, Gracely E, Podkameni G, Franklin L, Pall H. The Role of Health Disparities and Socioeconomic Status in Emergent Gastrointestinal Procedures. Health Equity. 2021;5:270-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zhu B, Li D, Ren Y, Li Y, Wang Y, Li K, Amin B, Gong K, Lu Y, Song M, Zhang N. Early versus delayed laparoscopic common bile duct exploration for common bile duct stone-related nonsevere acute cholangitis. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Nve E, Badia JM, Amillo-Zaragüeta M, Juvany M, Mourelo-Fariña M, Jorba R. Early Management of Severe Biliary Infection in the Era of the Tokyo Guidelines. J Clin Med. 2023;12:4711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | de C Ferreira LE, Baron TH. Acute biliary conditions. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;27:745-756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Butte JM, Hameed M, Ball CG. Hepato-pancreato-biliary emergencies for the acute care surgeon: etiology, diagnosis and treatment. World J Emerg Surg. 2015;10:13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kedia P, Gaidhane M, Kahaleh M. Endoscopic guided biliary drainage: how can we achieve efficient biliary drainage? Clin Endosc. 2013;46:543-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Amillo-Zaragüeta M, Nve E, Casanova D, Garro P, Badia JM. The Importance of Early Management of Severe Biliary Infection: Current Concepts. Int Surg. 2021;105:667-678. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wang YH, Xu ZH, Zhou YH, Sun SL, Xu ZW, Qi X, Zhou WJ, Sheng HQ, Zhao B, Mao EQ. The clinical characteristic of biliary-hyperlipidemic etiologically complex type of acute pancreatitis: a retrospective study from a tertiary center in China. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25:1462-1471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wang L, Lin N, Xin F, Zeng Y, Liu J. Comparison of long-term efficacy between endoscopic and percutaneous biliary drainage for resectable extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with biliary obstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:81-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/