Published online Jun 16, 2025. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v17.i6.103183

Revised: April 1, 2025

Accepted: May 18, 2025

Published online: June 16, 2025

Processing time: 212 Days and 8.8 Hours

Biliary anastomotic stricture (BAS) occurs in approximately 14%-20% of patients post-orthotopic liver transplantation (post-OLT). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) using multiple plastic stents (MPSs) or fully covered self-expandable metal stents (cSEMSs) represent the standard treatment for BAS post-OLT. Recently, cSEMSs have emerged as the primary option for managing BAS post-OLT.

To compare the resolution and recurrence of BAS rates in these patients.

This retrospective cohort study was conducted in a single tertiary care center (Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, São Paulo, Brazil). We reported the results of endoscopic therapy in patients with post-OLT BAS between 2012 and 2022. Patients were stratified into two groups according to therapy: (1) MPSs; and (2) cSEMSs. Primary endpoints were to compare stricture resolution and recurrence among the groups. The secondary endpoint was to identify predictive factors for stricture recurrence.

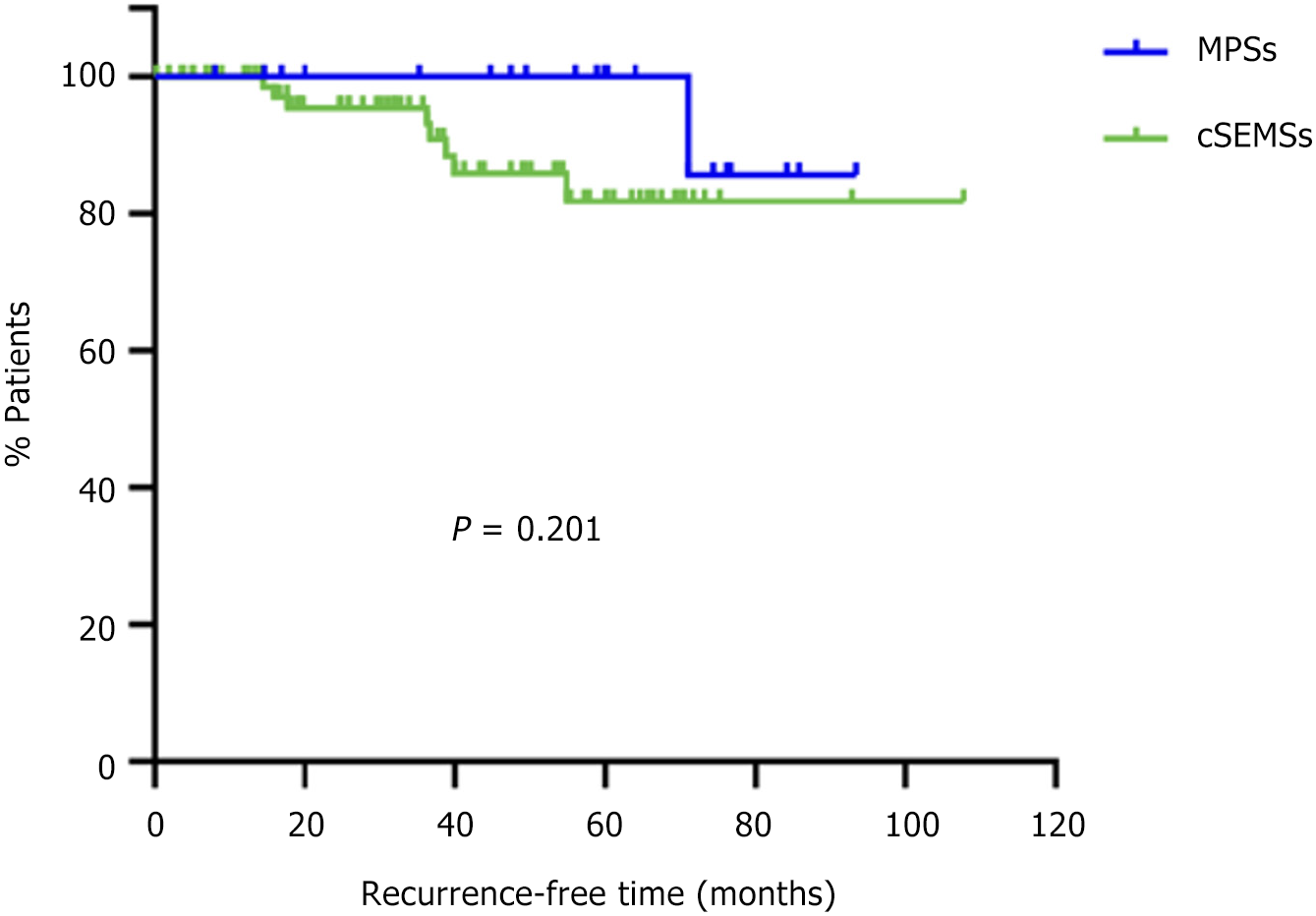

A total of 104 patients were included. Overall stricture resolution was 101/104 (97.1%). Stricture resolution was achieved in 83/84 patients (99%) in the cSEMS group and 18/20 patients (90%) in the MPS group (P = 0.094). Failure occurred in 3/104 patients (2.8%). Stricture recurrence occurred in 9/104 patients (8.7%). Kaplan-Meier analysis showed there was no difference in recurrence-free time among the groups (P = 0.201). A multivariate analysis identified the number of ERCP procedures (hazard ratio = 1.4; 95% confidence interval: 1.194-1.619; P < 0.001] and complications (hazard ratio = 2.8; 95% confidence interval: 1.008-7.724; P = 0.048) as predictors of stricture recurrence.

cSEMSs and MPSs were effective and comparable regarding BAS post-OLT resolution and recurrence. The number of ERCP procedures and complications were predictors of stricture recurrence.

Core Tip: This retrospective study evaluated the resolution and recurrence of endoscopic treatment using multiple plastic stents (MPSs) and covered self-expandable metal stents (cSEMSs) in patients with post-orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) biliary anastomotic stricture. Patients were stratified into two groups according to therapy: (1) MPSs; and (2) cSEMSs. Stricture resolution occurred in 101/104 patients (97.1%). Adverse events occurred in 48% in the cSEMS group and 10% in the MPS group. The cSEMSs and MPSs were effective and comparable regarding biliary anastomotic strictures post-OLT.

- Citation: Pinheiro LW, Martins FP, Ferrari AP, Tafner E, De Paulo GA, Della Libera E. Long-term outcomes of post-transplant biliary anastomotic strictures: Endoscopic therapy with plastic and metal stents. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2025; 17(6): 103183

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v17/i6/103183.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v17.i6.103183

Bile duct stenosis following liver transplantation is a common complication that can significantly impact patient morbidity[1-3]. Biliary anastomotic strictures (BAS), which account for approximately 80% of cases, are the predominant complications after orthotopic liver transplantation (post-OLT). In contrast non-anastomotic strictures occur less frequently in approximately 10%-25% of cases[4]. Anastomotic strictures can occur in the immediate postoperative period or up to 3 months after OLT and are related mainly to the surgical technique. Anastomotic strictures can also present as late complications, occurring years after OLT, and are caused by ischemia or fibrotic reactions caused by lesions located at or adjacent to the site of the biliary anastomosis[2].

Early anastomotic strictures (presenting within 1 month after-OLT) are generally amenable to endoscopic therapy, with resolution typically achieved within 3 months. Conversely, late anastomotic strictures (those presenting more than 1 month after OLT) may require extended and repeated therapy (12-24 months)[5]. The clinical presentation may vary depending on the severity of the stenosis and the patient´s characteristics but generally presents as asymptomatic elevation of liver enzymes, mainly in a cholestatic pattern (disproportionate elevation of alkaline phosphatase compared with aminotransferases). Abdominal pain, pruritus, or jaundice may also be present[2].

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is the standard treatment for post-OLT anastomotic strictures, with a lower morbidity rate than surgery (Roux-en-Y biliary enteric anastomosis) and percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage. Balloon dilation with stent placement is more effective than balloon dilation alone, with long-term response rates ranging from 70% to 100%[5,6]. Treatment using multiple plastic stents (MPSs) is based on a gradually increasing number of stents and hydrostatic balloon stricture dilation, with a duration of at least 1 year. MPSs have a high success rate (85%-97%) for the resolution of anastomotic strictures. However, it requires repeated endoscopic procedures[7].

Compared with MPSs, covered self-expandable metal stents (cSEMSs) may offer the advantages of longer stent patency and larger diameters, allowing faster benign stricture resolution with fewer procedures[7]. The disadvantage is a higher rate of stent migration, which could limit overall success[8]. The current report was a long-term retrospective study comparing stricture resolution and recurrence after endoscopic therapy using MPSs and cSEMSs for post-OLT BAS.

This retrospective study was conducted in a single private tertiary care center, Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, São Paulo, Brazil. This care center is a large, open-access, private tertiary care referral center where approximately 110 OLTs are performed yearly. The endoscopists involved had at least 10 years of experience. Our hospital is accredited by the Joint Commission International and is one of the most important transplant centers in South America.

We analyzed the results of endoscopic treatment in patients with post-OLT BAS from 2012 to 2022. The inclusion criteria were individuals aged between 18 years and 75 years with a diagnosis of post-OLT BAS and indications for endoscopic therapy, stricture located at least 2 cm below the hepatic confluence, and endoscopic treatment of stenosis with cSEMSs or MPSs. The exclusion criteria were pregnancy, non-anastomotic stricture, hilar stricture, hepatic artery stenosis or thrombosis, isolated biliary fistulae, death before 1 month of stent placement, radiological treatment exclusively with percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage, and patient refusal. For analysis purposes, patients were divided into two groups: (1) MPSs; and (2) cSEMSs. This study was approved by our institution’s Human Research Committee. All patients provided written consent before the database analysis.

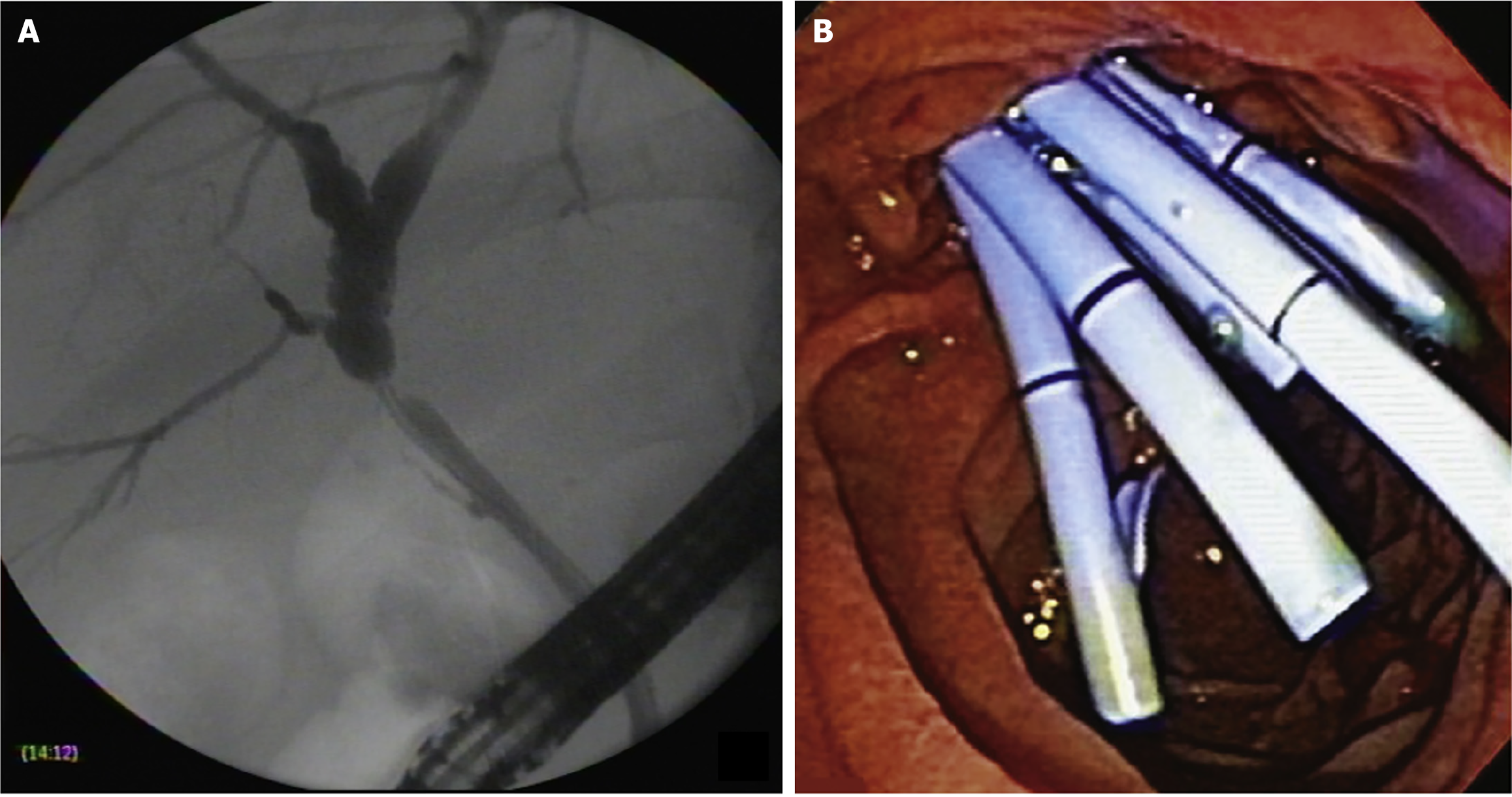

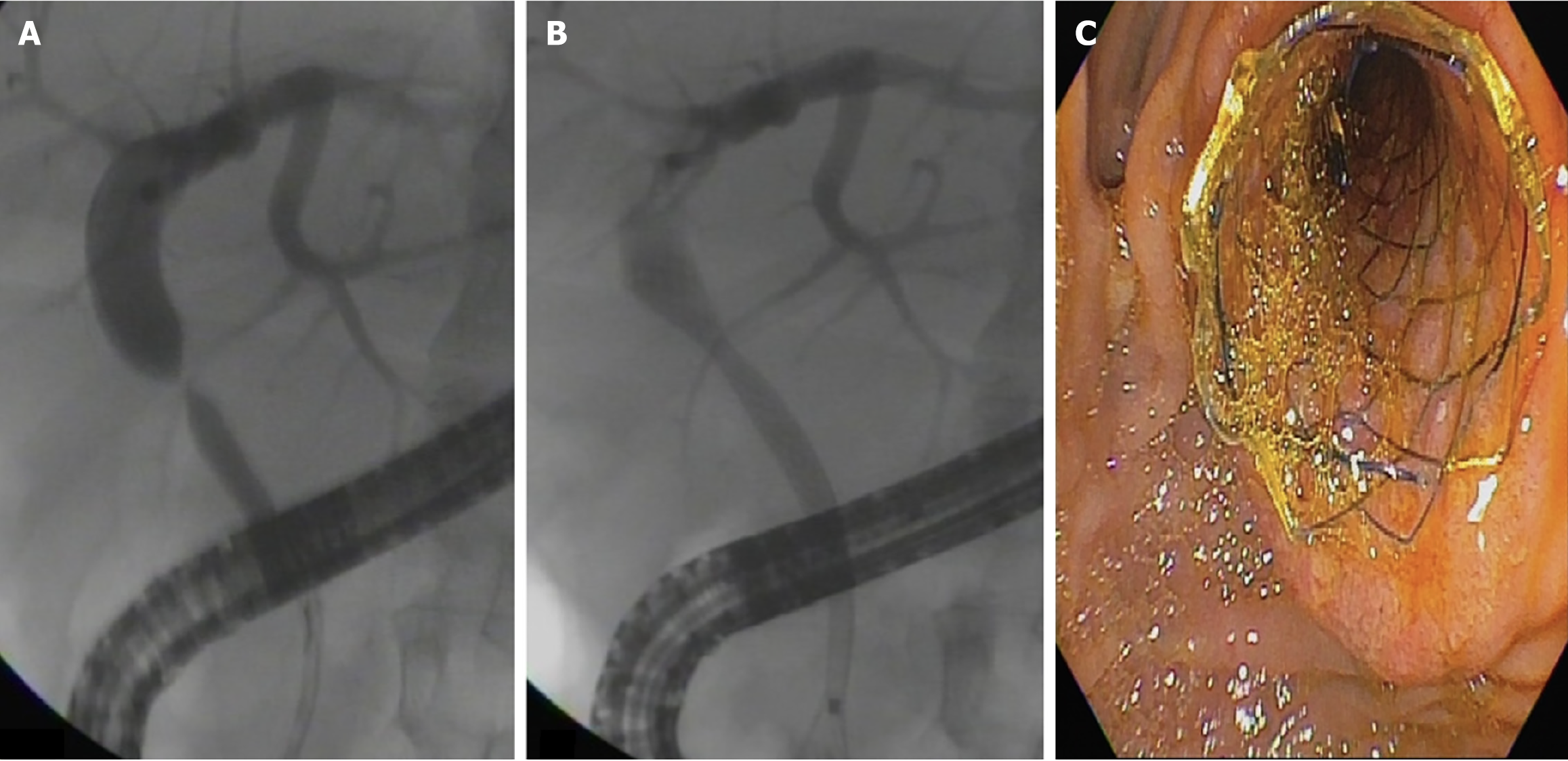

ERCP was performed using a therapeutic video duodenoscope (TJF-180, TJF-160, Olympus Optical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) with patients under monitored anesthesia using propofol or general anesthesia with intubation. After selective biliary cannulation, cholangiography was performed for the evaluation and characterization of the BAS followed by the placement of a guidewire. After the guidewire was positioned, biliary sphincterotomy was performed in patients with native papilla, and MPSs or cSEMSs were inserted. Balloon dilation of the stricture was performed in the MPS group and only if necessary to introduce the stent in the cSEMS group. According to the physician’s assessment, the length of the stent was determined during cholangiography to place the proximal end between the stricture and the hepatic hilum and the distal end into the duodenum. Patients treated with MPSs underwent ERCP every 3-4 months for stent exchange (with the placement of as many stents as possible in parallel, with balloon dilation whenever necessary).

At the beginning of the study period, patients treated with cSEMSs had their stent removed after 6 months. Later in the study, with new evidence from the literature, the cSEMS were removed after 12 months. Patients were monitored for clinical signs of cholestasis. ERCP was performed whenever necessary at any time during follow-up. Patients without complications were followed for at least 12 months to remove the stent and evaluate stricture resolution. Patients who developed BASs within 30 days of liver transplantation were initially treated with MPS placement. If the stricture persisted following stent removal, the patients were re-evaluated for further treatment with MPSs. The treatment strategies using MPSs and cSEMSs are shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

The primary aim was to compare stricture resolution and recurrence between the groups. Stricture resolution was defined as no stricture at final stent removal or only a minimum waist discerned on cholangiography that allowed easy passage of an inflated 12-mm extraction balloon. Treatment failure was defined as the persistence of the stricture at the final ERCP 12 months after the index procedure. Recurrence was defined as the appearance of a stricture at any period during follow-up after initial resolution.

The secondary aim of the clinical outcome was to identify possible predictive factors for stricture recurrence. Possible predictive factors for recurrence were sex, age, etiology (acute, chronic, retransplantation), the time interval from transplant to first ERCP, global migration of the stents, number of ERCP procedures, and group (MPS or cSEMS).

Descriptive analyses for quantitative data with a normal distribution were presented as the mean and standard deviation. Variables without a normal distribution were expressed as median and interquartile ranges (IQR) (25%-75%). Categorical variables were expressed as frequency and percentage. The assumption of a normal distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test.

The Mann-Whitney test was used to compare the variables, time of transplantation, age, and the total number of ERCP procedures, between patients who experienced recurrence and those who did not. Additionally, the χ² test or Fisher’s exact test was applied to compare the proportions between the two groups (MPS and cSEMS). The Kaplan-Meier curve was used to assess recurrence-free survival, and the log-rank test was used to compare curves.

Univariate Cox regression analysis was used to explore the correlation between predictor variables and outcome variables (recurrence). Variables that presented a P value ≤ 0.1 were included in the multivariate analysis using the Cox regression model stepwise backward likelihood ratio. A statistically significant value less than or equal to 5% (P ≤ 0.05) was used for all analyses except for the univariate Cox regression analysis.

Statistical tests were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 21.0 software (2012), and graphs were created using GraphPad Prism version 8 software.

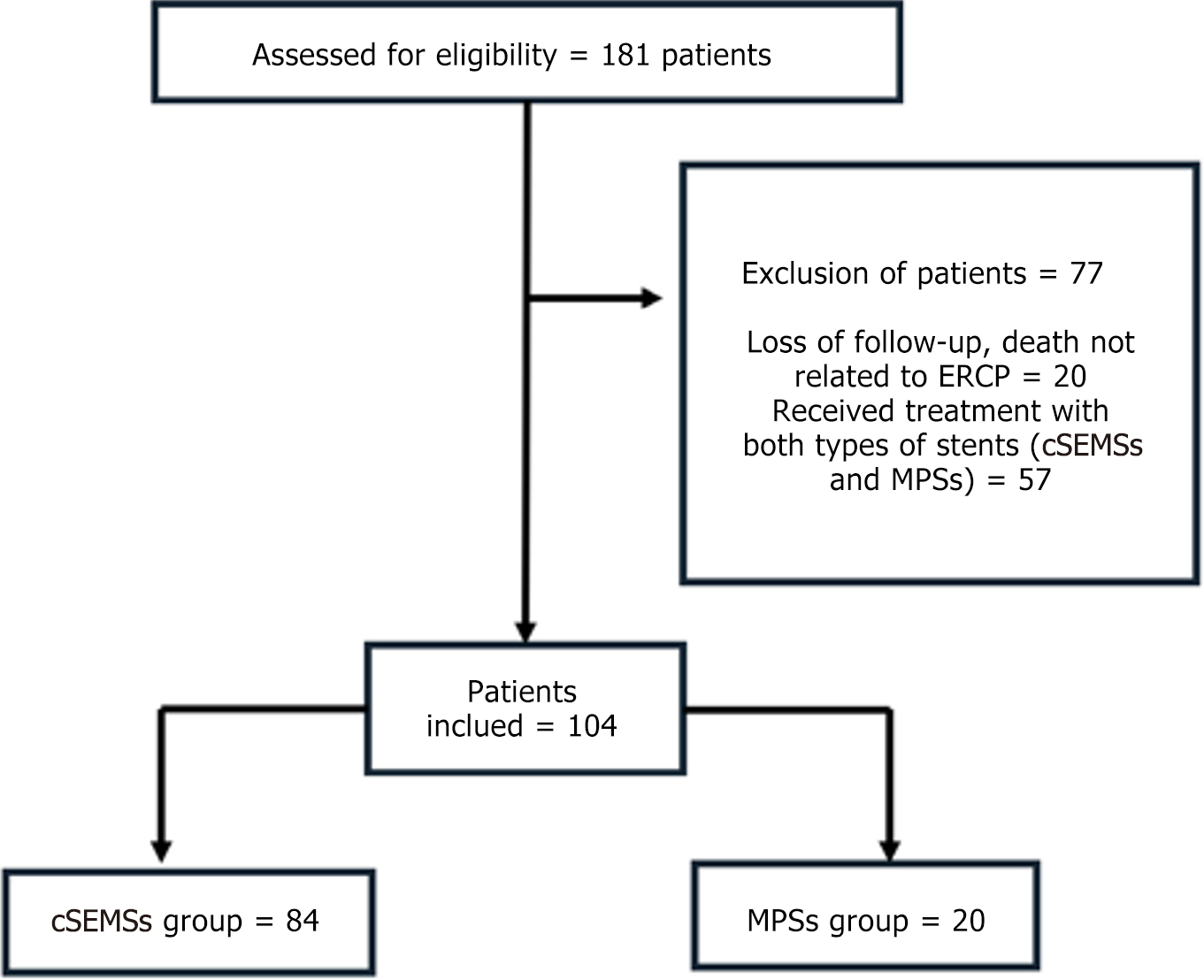

From 2012 to 2022 our hospital performed 1065 liver transplantations. A total of 181/1065 post-OLT patients with BAS (16.9%) were referred for ERCP. Twenty patients were treated with only one endoscopic procedure and excluded from the analysis (loss to follow-up, death not related to ERCP, or death before 1 month of stent placement). Fifty-seven patients who were treated with both MPSs and cSEMSs and who did not meet the criteria for treatment failure were excluded from both the study and the analysis.

The total number of patients included in this study (n = 104) was categorized according to the type of endoscopic therapy received: (1) cSEMS [n = 84; median age: 59 years; 64 males (76%)]; and (2) MPS [n = 20; median age: 57 years; 15 males (75%)] (Figure 3). The patients’ demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. A total of 349 ERCP pro

| Covered self-expandable metal stents (n = 84) | Multiple plastic stents (n = 20) | P value | |

| Male:female | 64:20 | 15:5 | > 0.999 |

| Age (years) | |||

| Median | 61 | 64 | 0.882 |

| Range | 20-77 | 26-79 | |

| Etiology | |||

| HCV | 26 | 6 | |

| HBV | 6 | 2 | |

| HCV + HBV | 2 | 0 | |

| Alcohol | 25 | 4 | |

| Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis | 8 | 2 | |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 4 | 3 | |

| Cryptogenic | 9 | 0 | |

| Wilson disease | 0 | 0 | |

| Acute liver failure | 2 | 2 | |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | 0 | 0 | |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | 2 | 0 | |

| Budd-Chiari | 1 | 0 | |

| Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency | 2 | 0 | |

| Familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy | 2 | 2 | |

| Hemochromatosis | 0 | 1 | |

| Hyperoxaluria | 0 | 0 | |

| Presence of hepatocellular carcinoma | 32 | 6 | 0.499 |

| Time from orthotopic liver transplantation to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (days) | |||

| Median | 153 | 77 | 0.111 |

| Range | 11-3.995 | 7-4.680 |

| Covered self-expandable metal stents | Multiple plastic stents | P value | |

| Stent treatment duration (days) | |||

| Median | 381 | 390 | 0.531 |

| Total number of ERCP | |||

| Median | 2 | 5 | 0.001 |

| Number of stents per ERCP/patient | |||

| Median | 1 | 4 | 0.001 |

| Range | 1-3 | 1-6 | |

| Total number of stents per patients | |||

| Median | 1 | 12 | 0.001 |

| Range | 1-3 | 1-27 | |

| Adverse events | |||

| Sphincterotomy bleeding | 3 | 1 | |

| Dilatation bleeding | 1 | 0 | |

| Choledocholithiasis/occlusion of stent | 25 | 7 | |

| Acute pancreatitis | 7 | 0 | |

| Cholangitis | 4 | 0 | |

| Perforation | 1 | 1 | |

| Stricture after sphincterotomy | 0 | 1 | |

| Hemobilia | 0 | 0 | |

| Abdominal pain | 0 | 0 | |

| Stricture caused by the stent | 3 | 0 | |

| Technical difficulty in removing the stent | 0 | 0 | |

| Bleeding removing the stent | 1 | 0 | |

| Death | 12 | 4 | 0.504 |

| Death related to ERCP procedure | 0 | 0 |

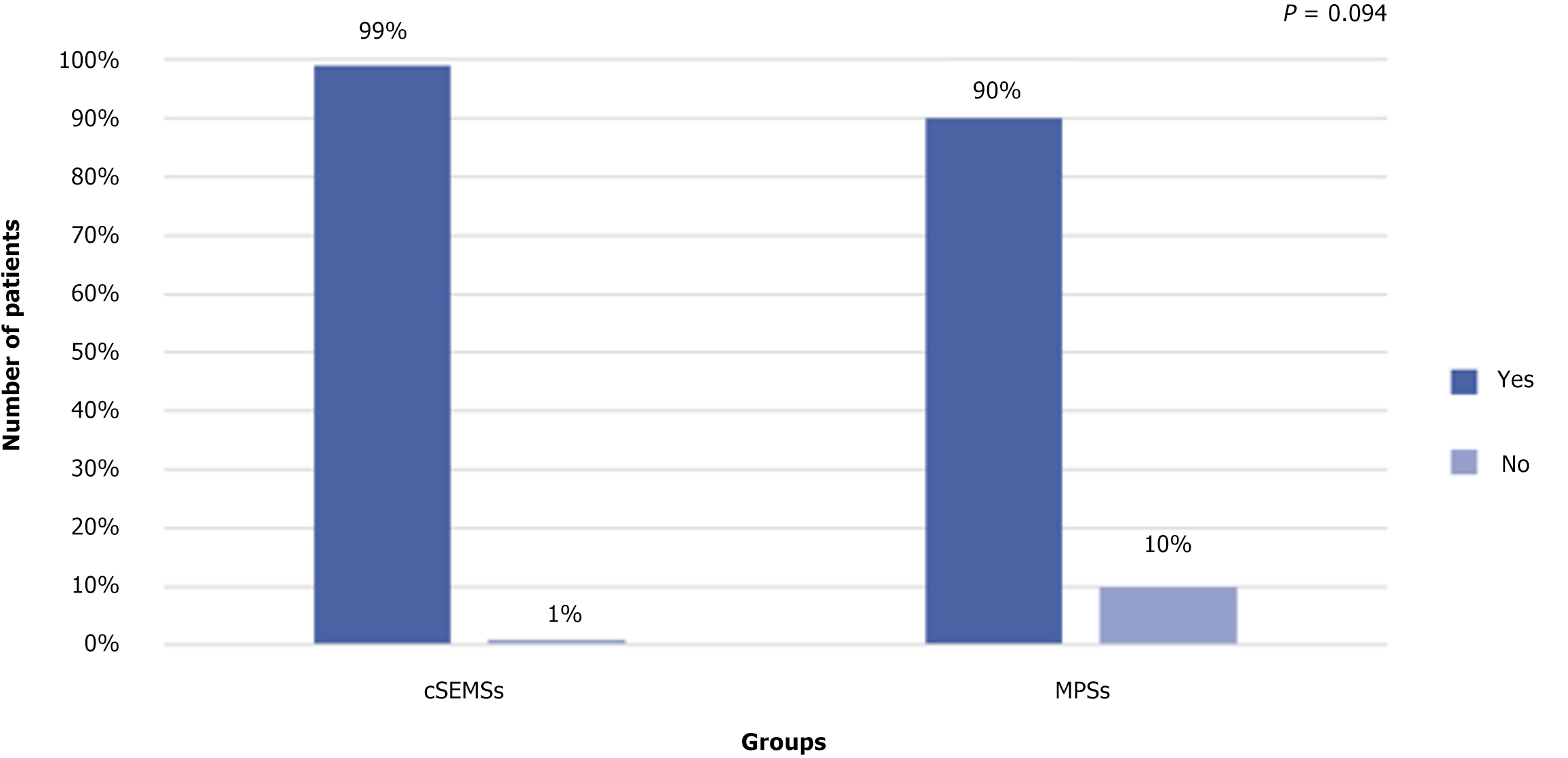

Stricture resolution: Overall stricture resolution occurred in 101/104 patients (97.1%): (1) 83/84 (99%) in the cSEMS group; and (2) 18/20 (90%) in the MPS group (P = 0.094). There was no difference between the cSEMS and MPS groups after an average 3-year follow-up. Endoscopic failure occurred in 3 patients: (1) Two in the MPS group; and (2) One in the cSEMS group. All were referred for surgery (Roux-en-Y bilioenteric anastomosis) (Figure 4).

Stricture recurrence: Stricture recurrence occurred in 9/101 patients (8.9%). Kaplan-Meier analysis of stricture resolution/freedom from recurence revealed that there was no difference in recurrence-free survival between the MPS and cSEMS groups (P = 0.201) (Figure 5).

A multivariate analysis identified the number of ERCP procedures (hazard ratio = 1.4; 95% confidence interval: 1.194-1.619; P < 0.001] and complications (hazard ratio = 2.8; 95% confidence: 1.008-7.724; P = 0.048) as predictors of stricture recurrence.

Adverse events occurred in 48% of patients in the cSEMS group and 10% of patients in the MPS group. The most common adverse event was choledocholithiasis/obstruction of the stent, accounting for 58.6% of all complications. It occurred in 28.6% of patients in the cSEMS group and 30% of patients in the MPS group (P = 0.899) and was treated with endoscopic therapy. Acute pancreatitis occurred in 7 patients (8.3%) with cSEMSs (P = 0.341). All the episodes were mild and were treated conservatively. Cholangitis was the third most common adverse event, occurring in 4 patients (4.8%) in the cSEMS group (P = 0.320). No acute pancreatitis or cholangitis was observed in the MPS group. The occurrence of other complications, such as bleeding following sphincterotomy or dilation, perforation, stenosis secondary to stent placement, hemobilia, bleeding after stent removal, and stricture after sphincterotomy, ranged from 1.8% to 5.4%. All complications were managed with clinical and/or endoscopic treatment. The overall mortality rate was 16/104 patients (15.4%) during follow-up, with cSEMSs accounting for 12/16 deaths (75%) and MPSs accounting for 4/16 deaths (25%). None of the deaths were related to endoscopic therapy.

This was a retrospective study that analyzed long-term resolution, recurrence, and predictive factors for the recurrence of post-OLT BAS treated with cSEMSs and MPSs. An analysis of 1065 patients who underwent liver transplantation from 2012 to 2022 revealed 181 (16.9%) patients with BAS, a rate very similar to that described in the literature[9-11]. The incidence of anastomotic stricture commonly increases after the first year post-OLT, as observed in our study and described in the literature[12,13]. Typically, these patients are asymptomatic and have abnormal liver biochemical test results.

ERCP is the standard treatment for post-OLT anastomotic strictures, and resolution rates can reach 100%[5,9,12,14]. Endoscopy therapy involves MPSs or cSEMSs[9,12-14]. In our study, we observed that patients whose stents were in place for 1 year presented an overall stricture resolution rate of 97.1%, and this high success rate is comparable to that reported in the literature[5,6,15,16]. We did not observe a significant difference in the resolution rate of biliary strictures when metal stents (cSEMSs) were compared with MPSs, as reported by other authors[3,17]. Biliary stent selection can be influenced by various factors, including the location, duration of anastomotic stricture after OLT, endoscopist preference, and availability of different stent options. At our center the choice of stents evolved over the course of the study, progressively changing from plastic (up to 2014) to metallic (from 2015 onward). Despite this shift, the patient groups analyzed (MPSs and cSEMSs) had comparable characteristics.

Endoscopic therapy using progressive MPS placement is highly efficacious[6]. However, the main disadvantage of using MPSs is the greater number of procedures performed (repeated approximately every 3 months) compared with patients using exclusively cSEMSs, which can be treated with 1 single cSEMS, and only undergoing two ERCP pro

The treatment lasted approximately 13 months, differing from what is reported in the literature, which indicates a stent removal period of 6 months to 1 year[6,14,15]. In our initial experience, cSEMSs were left in place for 6 months, and the outcomes were comparable with those of patients treated with MPSs for 12 months. Throughout the study we extended the duration of cSEMS placement to 12 months. This change suggests that a longer duration of stent placement may lead to better outcomes than the initial 6-month period[16]. Follow-up was conducted for at least 3 years after the resolution of the stricture. Recurrent strictures were observed within the first 3 years after endoscopic intervention and occurred with similar frequency in both treatment groups. This finding underscored the importance of more intensive follow-up during this period to facilitate early detection and management of strictures.

According to the Kaplan-Meier curve, the MPS group had a longer duration without recurrence, approaching 6 years. Nonetheless, the difference was not statistically significant, so no specific type of stent can be recommended based on these results.

In this study, the number of ERCP procedures per patient was negatively correlated with the success of endoscopic treatment and with an extended treatment duration. These findings suggest that a higher frequency of ERCP procedures and longer treatment duration are predictors of stricture recurrence, which is consistent with findings reported in the literature[19]. Among the adverse effects choledocholithiasis, acute pancreatitis, and cholangitis were the most common. According to the literature, there is indirect evidence suggesting that cSEMSs may be associated with post-ERCP pancreatitis[16].

Patients with both acute pancreatitis and cholangitis, classified as mild in severity, received only medical management. Patients with choledocholithiasis were managed endoscopically and, if necessary, underwent stent replacement. Although the cSEMS group experienced a greater number of complications in this study, there was no significant difference in the incidence of the three main complications, choledocholithiasis/obstruction, acute pancreatitis, and cholangitis, between the two endoscopic treatment groups.

Limitations of this single-center retrospective study included potential information bias stemming from data extracted from medical records and databases. Conversely, the strengths of the study lie in its large patient sample, prolonged follow-up periods after endoscopic treatment, and findings that align with published literature. Our findings indicated that endoscopic treatment was effective for post-OLT BAS regardless of the type of stent used (MPS or cSEMS). As previously described in the literature and confirmed by our study, there was no difference in the rates of stricture resolution and recurrence between the cSEMS and MPS groups[3,11].

Both cSEMSs and MPSs were effective and comparable in terms of stricture resolution and recurrence in patients with post-OLT BAS. The number of ERCP procedures and the occurrence of complications emerged as predictors of stricture recurrence.

| 1. | Kohli DR, Desai MV, Kennedy KF, Pandya P, Sharma P. Patients with post-transplant biliary strictures have significantly higher rates of liver transplant failure and rejection: A nationwide inpatient analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36:2008-2014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (37)] |

| 2. | Crismale JF, Ahmad J. Endoscopic Management of Biliary Issues in the Liver Transplant Patient. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2019;29:237-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (37)] |

| 3. | Amateau SK, Kohli DR, Desai M, Chinnakotla S, Harrison ME, Chalhoub JM, Coelho-Prabhu N, Elhanafi SE, Forbes N, Fujii-Lau LL, Kwon RS, Machicado JD, Marya NB, Pawa S, Ruan W, Sheth SG, Thiruvengadam NR, Thosani NC, Qumseya BJ; (ASGE Standards of Practice Committee Chair). American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline on management of post-liver transplant biliary strictures: methodology and review of evidence. Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;97:615-637.e11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (37)] |

| 4. | Dumortier J, Chambon-Augoyard C, Guillaud O, Pioche M, Rivory J, Valette PJ, Adham M, Ponchon T, Scoazec JY, Boillot O. Anastomotic bilio-biliary stricture after adult liver transplantation: A retrospective study over 20 years in a single center. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2020;44:564-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (43)] |

| 5. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Chathadi KV, Chandrasekhara V, Acosta RD, Decker GA, Early DS, Eloubeidi MA, Evans JA, Faulx AL, Fanelli RD, Fisher DA, Foley K, Fonkalsrud L, Hwang JH, Jue TL, Khashab MA, Lightdale JR, Muthusamy VR, Pasha SF, Saltzman JR, Sharaf R, Shaukat A, Shergill AK, Wang A, Cash BD, DeWitt JM. The role of ERCP in benign diseases of the biliary tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:795-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Poley JW, Ponchon T, Puespoek A, Bruno M, Roy A, Peetermans J, Rousseau M, Lépilliez V, Dolak W, Tringali A, Blero D, Carr-Locke D, Costamagna G, Devière J; Benign Biliary Stenoses Working Group. Fully covered self-expanding metal stents for benign biliary stricture after orthotopic liver transplant: 5-year outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;92:1216-1224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (37)] |

| 7. | Landi F, de'Angelis N, Sepulveda A, Martínez-Pérez A, Sobhani I, Laurent A, Soubrane O. Endoscopic treatment of anastomotic biliary stricture after adult deceased donor liver transplantation with multiple plastic stents versus self-expandable metal stents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transpl Int. 2018;31:131-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Conigliaro R, Pigò F, Bertani H; BASALT Group:, Greco S, Burti C, Indriolo A, Di Sario A, Ortolani A, Maroni L, Tringali A, Barbaro F, Costamagna G, Magarotto A, Masci E, Mutignani M, Forti E, Tringali A, Parodi MC, Assandri L, Marrone C, Fantin A, Penagini R, Cantù P; Liver Transplant Centers:, Di Benedetto F, Ravelli P, Vivarelli M, Agnes S, Mazzaferro V, De Carlis L, Andorno E, Cillo U, Rossi G. Migration rate using fully covered metal stent in anastomotic strictures after liver transplantation: Results from the BASALT study group. Liver Int. 2022;42:1861-1871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (37)] |

| 9. | Graziadei IW, Schwaighofer H, Koch R, Nachbaur K, Koenigsrainer A, Margreiter R, Vogel W. Long-term outcome of endoscopic treatment of biliary strictures after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:718-725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Albert JG, Filmann N, Elsner J, Moench C, Trojan J, Bojunga J, Sarrazin C, Friedrich-Rust M, Herrmann E, Bechstein WO, Zeuzem S, Hofmann WP. Long-term follow-up of endoscopic therapy for stenosis of the biliobiliary anastomosis associated with orthotopic liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2013;19:586-593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Visconti TAC, Bernardo WM, Moura DTH, Moura ETH, Gonçalves CVT, Farias GF, Guedes HG, Ribeiro IB, Franzini TP, Luz GO, Dos Santos MEDL, de Moura EGH. Metallic vs plastic stents to treat biliary stricture after liver transplantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis based on randomized trials. Endosc Int Open. 2018;6:E914-E923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tal AO, Finkelmeier F, Filmann N, Kylänpää L, Udd M, Parzanese I, Cantù P, Dechêne A, Penndorf V, Schnitzbauer A, Friedrich-Rust M, Zeuzem S, Albert JG. Multiple plastic stents versus covered metal stent for treatment of anastomotic biliary strictures after liver transplantation: a prospective, randomized, multicenter trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86:1038-1045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Kao D, Zepeda-Gomez S, Tandon P, Bain VG. Managing the post-liver transplantation anastomotic biliary stricture: multiple plastic versus metal stents: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:679-691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zhang CC, Rupp C, Exarchos X, Mehrabi A, Koschny R, Schaible A, Sauer P. Scheduled endoscopic treatment of biliary anastomotic and nonanastomotic strictures after orthotopic liver transplantation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;97:42-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (37)] |

| 15. | Keane MG, Devlin J, Harrison P, Masadeh M, Arain MA, Joshi D. Diagnosis and management of benign biliary strictures post liver transplantation in adults. Transplant Rev (Orlando). 2021;35:100593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (37)] |

| 16. | Martins FP, De Paulo GA, Contini MLC, Ferrari AP. Metal versus plastic stents for anastomotic biliary strictures after liver transplantation: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:131.e1-131.e13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Coté GA, Slivka A, Tarnasky P, Mullady DK, Elmunzer BJ, Elta G, Fogel E, Lehman G, McHenry L, Romagnuolo J, Menon S, Siddiqui UD, Watkins J, Lynch S, Denski C, Xu H, Sherman S. Effect of Covered Metallic Stents Compared With Plastic Stents on Benign Biliary Stricture Resolution: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;315:1250-1257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Jang S, Stevens T, Lopez R, Chahal P, Bhatt A, Sanaka M, Vargo JJ. Self-Expandable Metallic Stent Is More Cost Efficient Than Plastic Stent in Treating Anastomotic Biliary Stricture. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65:600-608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (37)] |

| 19. | Cai XB, Zhu F, Wen JJ, Li L, Zhang RL, Zhou H, Wan XJ. Endoscopic treatment for biliary stricture after orthotopic liver transplantation: success, recurrence and their influencing factors. J Dig Dis. 2012;13:642-648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/