Published online Dec 16, 2025. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v17.i12.110594

Revised: August 26, 2025

Accepted: October 29, 2025

Published online: December 16, 2025

Processing time: 189 Days and 14.9 Hours

Oral and pharyngolaryngeal papillomas are occasionally detected during esopha

To distinguish oral and pharyngolaryngeal papillomas from elevated squamous carcinomas, this study examined their endoscopic features.

Forty-seven patients with oral or pharyngeal papilloma participated in this study. The endoscopic characteristics of papillomas were identified by focusing on narrowband and blue laser imaging representations.

Papillomas were classified into three patterns based on their endoscopic features: Salmon roe-like polyps, polyps without capillary transparency, and pinecone-like polyps, with salmon roe-like polyps most prevalent (48.9%). We subsequently analyzed features differentiating papillomas and squamous cell carcinomas in the same region and found that squamous cell carcinomas exhibited at least one of the following three features: Uneven or absent lobulated structure, irregular morphology of capillaries, and coexistence of flat lesions. In contrast, papillomas displayed a uniform lobulated structure, homogeneous or non-visible capillaries, and an absence of flat components. When any of these characteristics were present, two endoscopic specialists evaluated the lesions for the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma, with sensitivities of 100% and 97.6% and specificities of 68.9% and 93.3%.

Understanding distinct endoscopic patterns of oropharyngeal papillomas and squamous cell carcinomas provides valuable guidance to endoscopists performing esophagogastroduodenoscopy.

Core Tip: This retrospective study highlighted the endoscopic features of oral and pharyngolaryngeal papillomas and identified three distinct morphological patterns: Salmon roe-like, polyps without capillary transparency, and pinecone-like. By contrasting these features with those of squamous cell carcinomas, namely, uneven lobulated structures, irregular capillaries, and flat lesion components, this study provides practical guidance for distinguishing these lesions during esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Our findings may reduce unnecessary biopsies and improve diagnostic accuracy, offering endoscopists valuable insights into oropharyngeal region evaluations. To our knowledge, this is the first detailed analysis of the endoscopic patterns of papillomas in these regions.

- Citation: Iwamuro M, Tanaka T, Hamada K, Kono Y, Kawano S, Kawahara Y, Otsuka M. Endoscopic features of oral and pharyngolaryngeal papillomas and their role in distinguishing squamous cell carcinoma. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2025; 17(12): 110594

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v17/i12/110594.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v17.i12.110594

A papilloma within the oral and pharyngolaryngeal regions is a benign polyp with wart-like projections that develop in the epithelial tissues of the mouth, throat, and larynx[1-3]. These neoplasms are typically non-cancerous and are often associated with exophytic growth patterns. Microscopically, pharyngeal papillomas exhibit specific features including a papillary architectural arrangement, hyperkeratosis, koilocytosis, and the presence of fibrovascular cores[4]. As papillomas are generally considered benign and pose a low risk of malignancy, therapeutic intervention is selectively reserved for cases in which symptomatic manifestations require attention. In contrast, recent advancements in endoscopic technology have facilitated the detection of squamous cell carcinoma within the oral cavity and pharyngolaryngeal region during esophagogastroduodenoscopy[5-9]. The importance of promptly distinguishing papilloma from squamous cell carcinoma during endoscopic observation has been increasingly recognized. However, to date, the endoscopic characteristics of papillomas in the oral and pharyngolaryngeal regions have not been sufficiently investigated, with research on their differentiation from squamous cell carcinomas lacking. Thus, in this study, we retrospectively analyzed at our facility the endoscopic features of papillomas in the oral and pharyngolaryngeal regions and investigated the characteristics that distinguish them from squamous cell carcinomas. Additionally, to examine the involvement of human papillomavirus (HPV), p16 immunostaining was conducted[10].

A database search of the pathology reports at our hospital identified 166 patients diagnosed with squamous papillomas in the oral and pharyngolaryngeal regions between January 2012 and February 2023. Among them, 97 were excluded because esophagogastroduodenoscopy was not indicated. We further excluded 22 patients because oral or phar

This retrospective study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee of our hospital (No. 2310-007). The Ethics Committee of our hospital waived the requirement for written informed consent because of the retrospective nature of the study and the use of anonymous clinical data for analysis.

For comparisons between the two groups, statistical analyses, including t-tests, χ2 tests, and F-tests, were performed using JMP Pro 16.0.0 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

The primary subjects of this study were patients with papilloma in the oral and pharyngolaryngeal regions. They consisted of 33 males and 14 females, with an average age of 66.3 ± 10.9 years (mean ± SD, range: 44-85 years). Regarding the location of the tumors, we categorized the uvula and base of the tongue separately, although both structures are anatomically encompassed within the pharynx. The tumor locations were as follows: Pharynx (n = 34), palate (n = 4), uvula (n = 3), larynx (n = 3), base of the tongue (n = 2), and gingiva (n = 1).

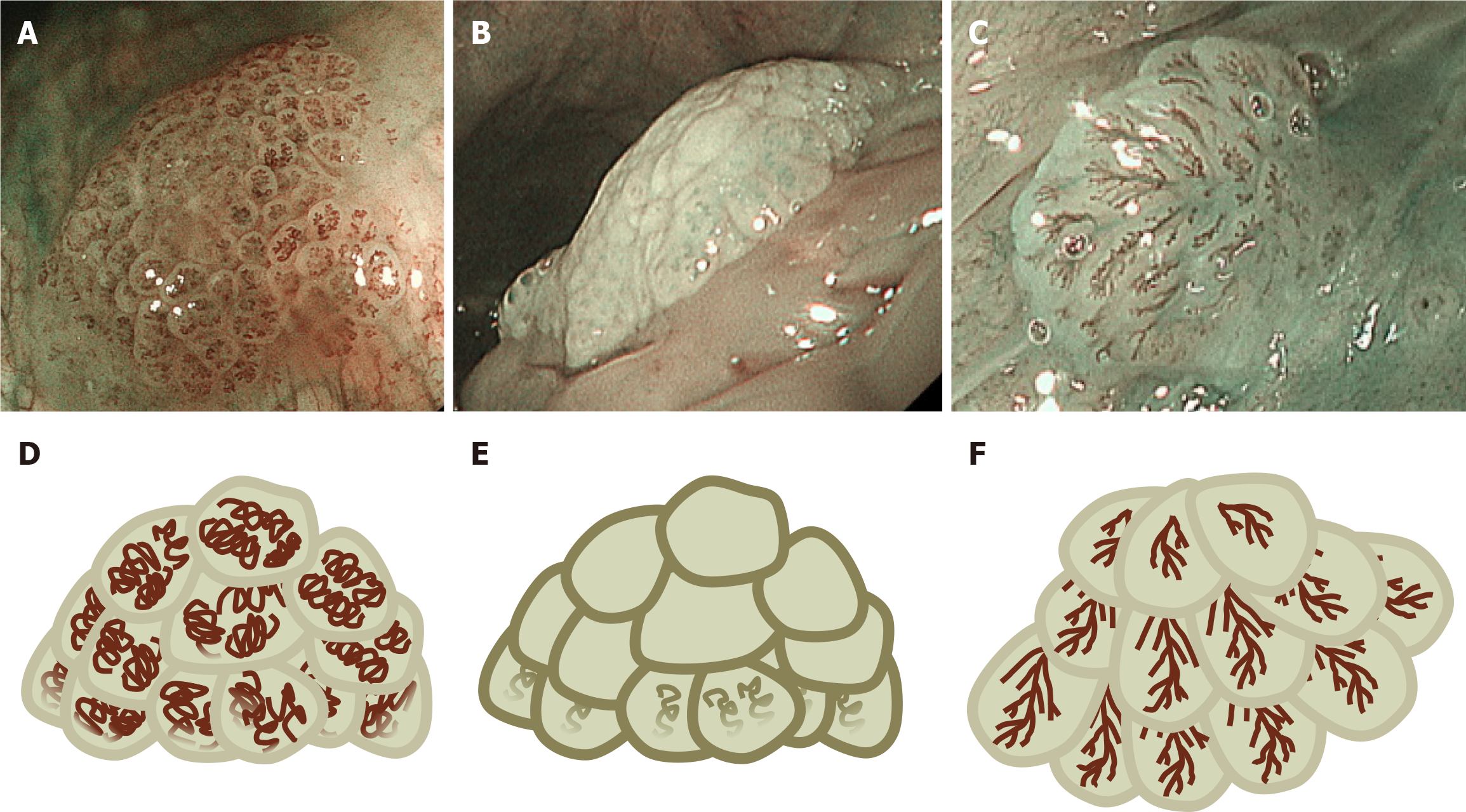

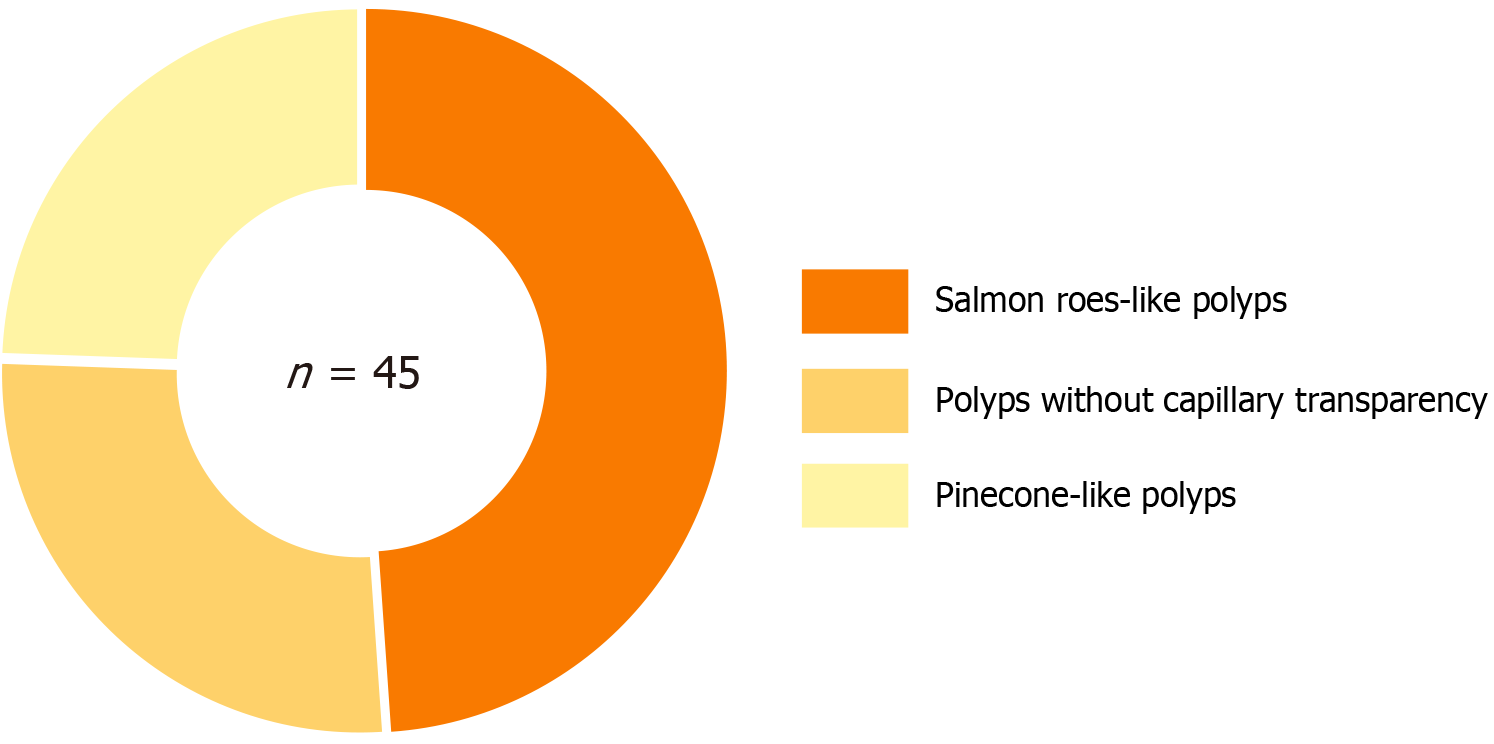

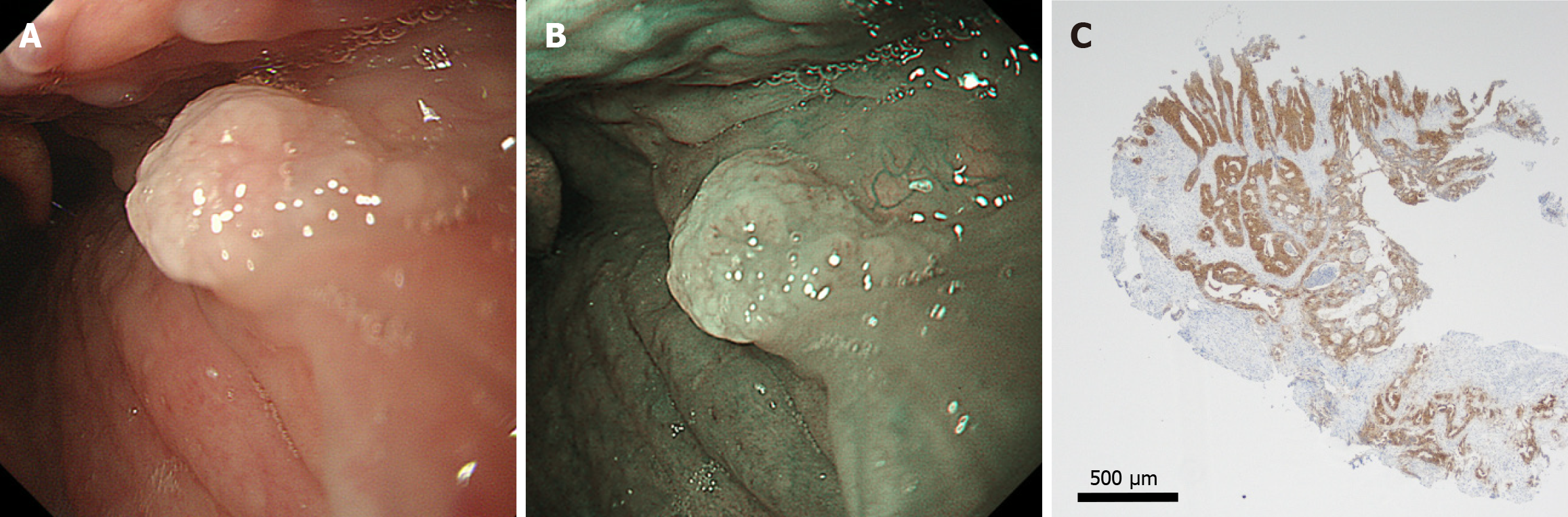

All papillomas identified in the oral and pharyngolaryngeal regions presented as protruding lesions. Observations using NBI or BLI were conducted on 45 lesions, which typically revealed an even-sized lobular architecture. Upon reviewing the NBI and BLI images, we classified the papillomas into three distinct patterns based on their endoscopic features (Figure 1, Supplementary Figure 1): (1) Salmon roe-like polyps (elevated lesion with multiple rounded lobules showing translucent capillary structures). This lesion is elevated with the aggregation of multiple small nodules. Coil-shaped capillaries resembling salmon roe or frog eggs were internally visible in each nodule; (2) A polyp without capillary transparency (elevated lesion with aggregated nodules lacking visible intranodular capillary structures). Similar to the previous type of polyp, this lesion is elevated with the aggregation of multiple small nodules. However, no capillary transparency or only slightly visible capillaries were observed; and (3) Pinecone-like polyps (elevated lesions with layered, scale-like structures and linear capillary patterns resembling leaf veins) resemble a pinecone, which consists of overlapping scale-like components, with capillaries resembling leaf veins visible in each component. Among these classifications, salmon roe-like polyps were the most prevalent (n = 22, 48.9%), followed by polyps without capillary transparency (n = 12, 26.7%), and pinecone-like polyps (n = 11, 24.4%) (Figure 2).

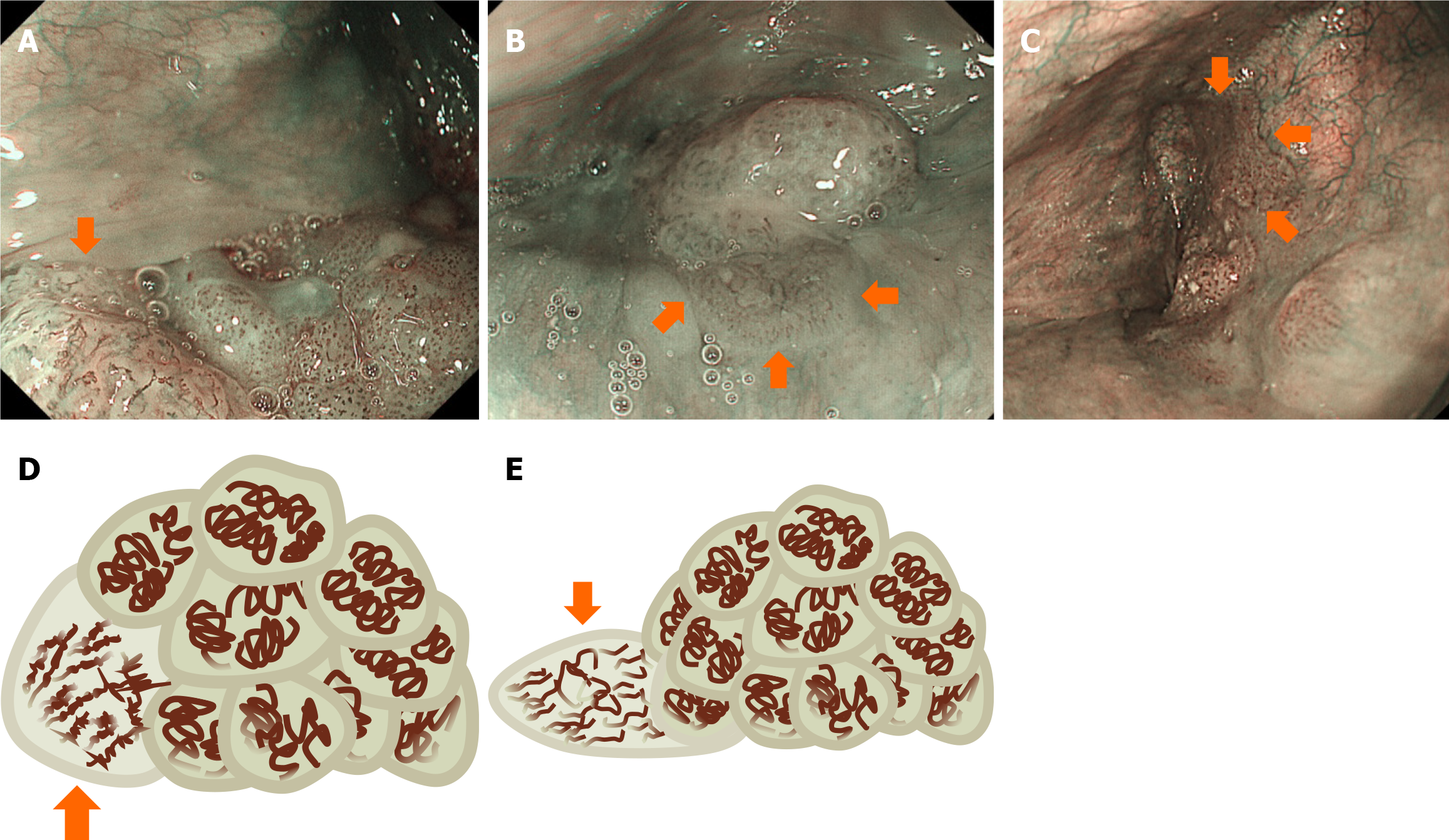

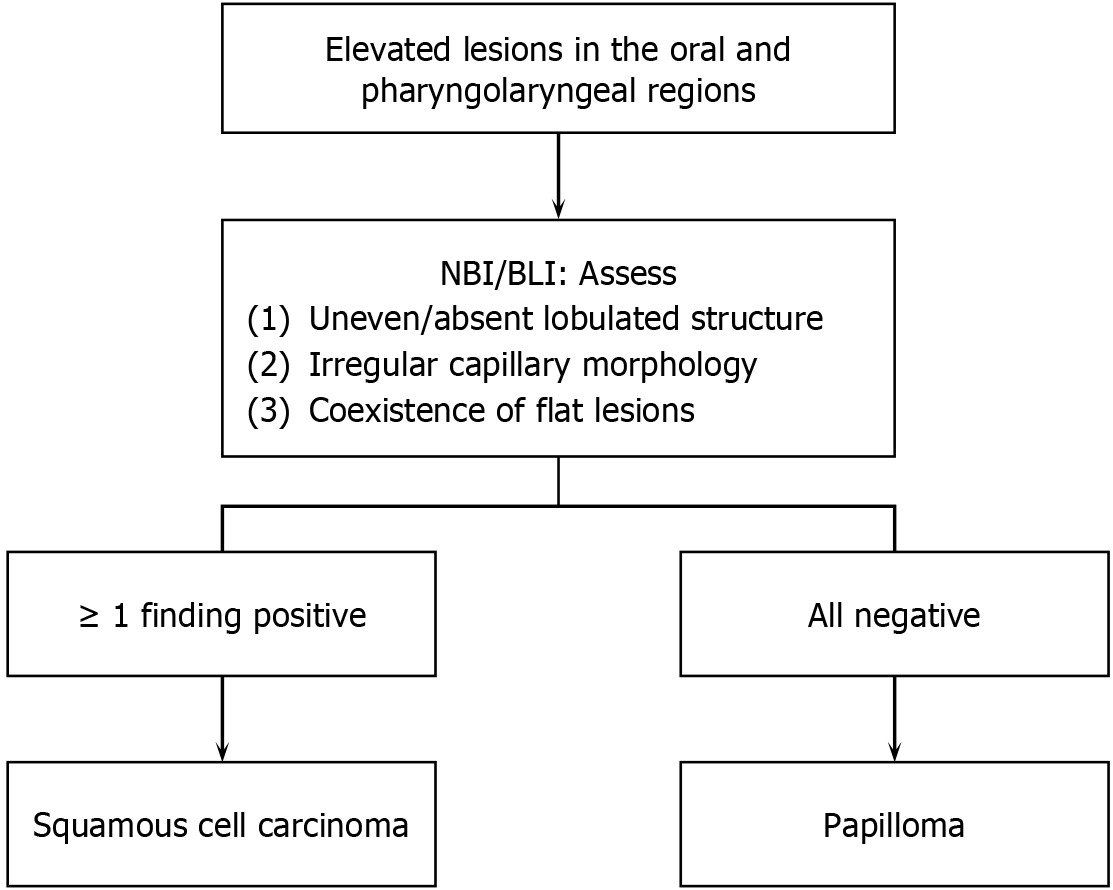

Subsequently, we reviewed the NBI and BLI images of 41 oral and pharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma lesions with elevated morphology (Figure 3). We investigated the differences in endoscopic findings between squamous cell carcinoma and papillomas. Squamous cell carcinoma shows the following three distinctly different characteristics from papilloma: (1) Uneven or absent lobulated structure; (2) Irregular morphology of capillaries, including variations in caliber and tortuosity depending on the parts within the lesion; and (3) Coexistence of flat lesions. In contrast, papillomas exhibit a uniform lobulated structure, a homogeneous pattern of capillaries or nonvisible capillaries, and the absence of flat components.

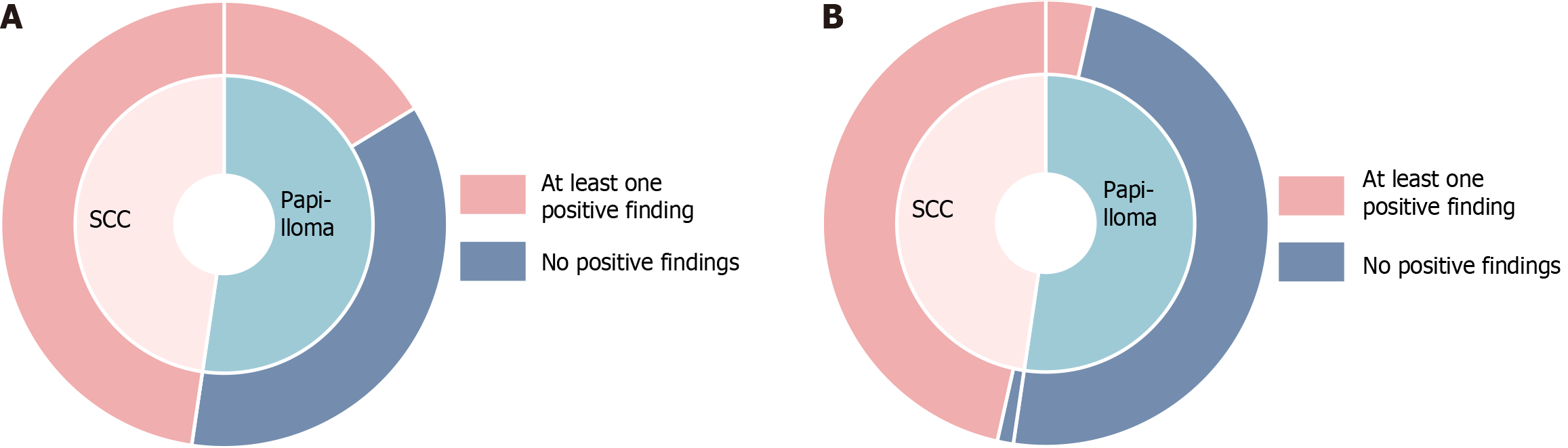

Two endoscopy experts (Hamada K and Kono Y), board-certified endoscopists at the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society, evaluated these three characteristics in 45 papilloma and 41 squamous cell carcinoma cases. The interobserver agreement was calculated using the kappa statistic. The kappa coefficients for (1) Uneven or absent lobulated structures; (2) Irregular capillary morphology; and (3) Coexistence of flat lesions were 0.70, 0.65, and 0.73, respectively. Lesions were diagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma when at least one characteristic was present, and papilloma when none of these characteristics were present. Based on this definition, the diagnostic performance for correctly identifying squamous cell carcinoma was as follows: The sensitivity and specificity were 100% and 68.9% for Hamada K, respectively (Figure 4A), and 97.6% and 93.3% for Kono Y, respectively (Figure 4B). Alternatively, when lesions with at least two characteristics were diagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma, and those with no or only one of the three characteristics were diagnosed as papilloma, the sensitivity and specificity were 87.8% and 93.3% for Hamada K and 97.6% and 95.6% for Kono Y. Furthermore, when lesions with all three characteristics were diagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma and those with two or fewer characteristics were diagnosed as papilloma, the sensitivity and specificity were 48.8% and 97.8% for Kono Y and 53.7% and 100% for Hamada K. A papilloma in the pharynx of a 55-year-old male was classified as a polyp without capillary transparency and was positive for p16 staining (Figure 5). The remaining 44 patients tested negative for p16. Accordingly, no correlations were observed between endoscopic classification and HPV status.

To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the endoscopic features of oral and pharyngolaryngeal papillomas. Diseases in the oral and pharyngolaryngeal regions, which otolaryngologists and dentists have traditionally managed, have been increasingly detected through esophagogastroduodenoscopy in recent years. This may be attributed to various innovations, including the improvement of equipment like magnifying observation functions and image-enhancing functions such as NBI and BLI[5-9]. The sensitivity and specificity of NBI for the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma in the oral and pharyngolaryngeal regions have been reported to range from 81% to 98% and 78% to 100%, respectively, which are higher than those achieved with conventional white-light imaging[11]. Techniques involving the Valsalva maneuver, patient vocalization, and concurrent use of narcotic drugs, such as pethidine hydrochloride, have contributed to this trend[12,13]. Squamous cell carcinoma is the most noteworthy concern in the oral and pharyngolaryngeal regions because it affects patient outcomes. In contrast, because papillomas are benign neoplasms that are often found in these areas, knowledge of the distinguishing features between the two lesions is important for endoscopists. Since no previous studies have described the endoscopic findings of papillomas in these regions, our report provides novel insights that will establish a foundation for future comparative and validation studies.

We found that oral and pharyngolaryngeal papillomas typically appear as salmon roe-like polyps (48.9%), polyps without capillary transparency (26.7%), or pinecone-like polyps (24.4%). While no studies have reported the endoscopic features of oral and pharyngolaryngeal papillomas, few have analyzed the endoscopic findings of esophageal papillomas. Wong et al[14] investigated 41 esophageal polypoid lesions, including 24 patients with esophageal papillomas. The authors reported that among the 24 esophageal papilloma lesions, all three features of exophytic growth, wart-like shape, and crossing surface vessels were observed in 15 lesions (62.5%). Referring to the endoscopic images published in the paper and considering the feature of “crossing surface vessels”, the typical appearance of esophageal papilloma is thought to correspond to what we referred to as “pinecone-like polyps” in our study. In the present study, pinecone-like polyps accounted for only a quarter of the oral and pharyngolaryngeal papillomas. At the same time, approximately half were salmon roe-like polyps, and the remaining quarter exhibited polyp morphology without capillary transparency. These results indicate that most papillomas in the oral and pharyngolaryngeal regions may have different endoscopic features from those in the esophageal area.

Comparison of endoscopic images between squamous cell carcinomas and papillomas revealed three features, particularly in squamous cell carcinomas, including an uneven or absent lobulated structure, irregular morphology of capillaries, and coexistence of flat lesions. In contrast, papillomas exhibited a uniform lobulated structure, a homogeneous pattern of capillaries or non-visible capillaries, and the absence of flat components. We believe that knowledge of these findings will help distinguish between these two diseases. Two expert endoscopists applied these criteria and diagnosed squamous cell carcinoma with commendable sensitivity rates of 100% and 97.6% when any one of the three findings was present. However, the specificity was variable, ranging from 68.9% to 93.3%, likely owing to the subjective nature of the assessment. When lesions with two or more characteristics were diagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma and those with none or only one of the three characteristics were diagnosed as papilloma, the sensitivity and specificity rates were 87.8% and 97.6% and 93.3% and 95.6%, respectively, indicating an increase in specificity. In contrast, this approach also results in reduced sensitivity, which implies that when endoscopic findings are used to diagnose a lesion as a papilloma and a biopsy is withheld under this criterion, the likelihood of missing squamous cell carcinoma increases. To appropriately detect squamous cell carcinoma while minimizing unnecessary biopsies in the oropharyngeal region, the strategy of diagnosing lesions as papillomas and withholding biopsy only when none of the three endoscopic characteristics are present appears to be the most reasonable (Figure 6). Inexperienced endoscopists may have difficulty interpreting elevated lesions in the oral and pharyngolaryngeal regions. However, the pathognomonic features proposed in this study were easily recognizable. Employing these three findings will reduce unnecessary biopsies. This is particularly significant in this anatomical region, where biopsies can induce oral bleeding and discomfort, underscoring the importance of reducing unnecessary biopsies. Accumulating more cases and discovering additional findings characteristic of squamous cell carcinoma may enhance the precision of endoscopic diagnosis.

The incidence of HPV infection in papillomas varies between studies. The prevalence of HPV infection among oral, pharyngolaryngeal, and esophageal papillomas is most pronounced in laryngeal papillomas (76%-94%), followed by oral (27%-48%), sinonasal (25%-40%), esophageal (11%-57%), and oropharyngeal papillomas (6%-7%)[15-19]. In the present study, we used p16 staining, which has high sensitivity and specificity for detecting HPV infection[20]. Only one case was positive for p16, resulting in a low infection rate (1/47, 2.1%). HPV infection has been reported to be more common in the larynx than in the pharynx, and pharyngeal papillomas accounted for the majority (34/47, 72.3%) of the cases in our study. Therefore, although we considered these results reasonable and did not detect HPV DNA, it should be noted that false negatives may have occurred owing to differences in the measurement methods.

This study has several limitations. First, this was a retrospective study performed at a single institution, and the number of enrolled patients was relatively small. Second, patients were selected based on pathological diagnosis; thus, papillomas that were not biopsied or excised were excluded from the analysis, which introduced a selection bias. Third, determining whether the distinction between papillomas and squamous cell carcinomas based on endoscopic findings is truly beneficial requires verification through prospective studies. Fourth, none of the patients underwent follow-up; therefore, we could not evaluate the progression or presence of dysplastic features. Despite these limitations, to our knowledge, this study is the first investigation of the endoscopic findings of oral and pharyngeal papillomas.

We investigated 47 oral and pharyngolaryngeal papilloma lesions and found that they were morphologically classified as salmon roe-like polyps, polyps without capillary transparency, or pinecone-like polyps. In contrast, the three endoscopic findings for the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma of the oral and pharyngolaryngeal regions are uneven or absent lobulated structures, irregular morphology of capillaries, and the coexistence of flat lesions; thus, a biopsy should be performed if any of these findings are present. Conversely, a biopsy can be waived if these features are absent, assuming that the lesions are more likely to be papillomas than squamous cell carcinomas. We believe that these valuable insights offer guidance to endoscopists who observe the oropharyngeal region using esophagogastroduodenoscopy.

| 1. | Iwamuro M, Hamada K, Kawano S, Kawahara Y, Otsuka M. Review of oral and pharyngolaryngeal benign lesions detected during esophagogastroduodenoscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;15:496-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ding D, Yin G, Guo W, Huang Z. Analysis of lesion location and disease characteristics of pharyngeal and laryngeal papilloma in adult. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2023;280:289-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hirai R, Makiyama K, Higuti Y, Ikeda A, Miura M, Hasegawa H, Kinukawa N, Ikeda M. Pharyngeal squamous cell papilloma in adult Japanese: comparison with laryngeal papilloma in clinical manifestations and HPV infection. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;269:2271-2276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Capper JW, Bailey CM, Michaels L. Squamous papillomas of the larynx in adults. A review of 63 cases. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1983;8:109-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hamada K, Ishihara R, Yamasaki Y, Akasaka T, Arao M, Iwatsubo T, Shichijo S, Matsuura N, Nakahira H, Kanesaka T, Yamamoto S, Takeuchi Y, Higashino K, Uedo N, Kawahara Y, Okada H. Transoral endoscopic examination of head and neck region. Dig Endosc. 2018;30:516-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Iwatsubo T, Ishihara R, Nakagawa K, Ohmori M, Iwagami H, Matsuno K, Inoue S, Nakahira H, Matsuura N, Shichijo S, Maekawa A, Kanesaka T, Yamamoto S, Takeuchi Y, Higashino K, Uedo N, Higuchi K. Pharyngeal observation via transoral endoscopy using a lip cover-type mouthpiece. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34:1384-1389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ashizawa H, Yamamoto Y, Mukaigawa T, Kawata N, Maeda Y, Yoshida M, Minamide T, Hotta K, Imai K, Ito S, Takada K, Sato J, Ishiwatari H, Matsubayashi H, Ono H. Feasibility of endoscopic resection for superficial laryngopharyngeal cancer after radiotherapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;39:2796-2803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tsuji K, Doyama H, Takeda Y, Takemura K, Yoshida N, Kito Y, Asahina Y, Ito R, Nakanishi H, Hayashi T, Inagaki S, Tominaga K, Waseda Y, Tsuji S, Yamada S, Hino S, Okada T. Use of transoral endoscopy for pharyngeal examination: cross-sectional analysis. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:344-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Piazza C, Dessouky O, Peretti G, Cocco D, De Benedetto L, Nicolai P. Narrow-band imaging: a new tool for evaluation of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Review of the literature. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2008;28:49-54. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Gharzai LA, Morris E, Suresh K, Nguyen-Tân PF, Rosenthal DI, Gillison ML, Harari PM, Garden AS, Koyfman S, Caudell JJ, Jones CU, Mitchell DL, Krempl G, Ridge JA, Gensheimer MF, Bonner JA, Filion E, Dunlap NE, Stokes WA, Le QT, Torres-Saavedra P, Mierzwa M, Schipper MJ. Surrogate endpoints in clinical trials of p16-positive squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2024;25:366-375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hosono H, Katada C, Kano K, Kimura A, Tsutsumi S, Miyamoto S, Ichinoe M, Furue Y, Tanabe S, Koizumi W, Yamashita T. Evaluation of the usefulness of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and the Valsamouth(Ⓡ) by an otolaryngologist in patients with Hypopharyngeal cancer. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2021;48:265-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Saraniti C, Greco G, Verro B, Lazim NM, Chianetta E. Impact of Narrow Band Imaging in Pre-Operative Assessment of Suspicious Oral Cavity Lesions: A Systematic Review. Iran J Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;33:127-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kato M, Hayashi Y, Takehara T. Valsalva maneuver to visualize the closed hypopharyngeal space during transoral endoscopy using a novel dedicated mouthpiece. Dig Endosc. 2019;31:e24-e25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wong MW, Bair MJ, Shih SC, Chu CH, Wang HY, Wang TE, Chang CW, Chen MJ. Using typical endoscopic features to diagnose esophageal squamous papilloma. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:2349-2356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Syrjänen S, Syrjänen K. HPV-Associated Benign Squamous Cell Papillomas in the Upper Aero-Digestive Tract and Their Malignant Potential. Viruses. 2021;13:1624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Beigh A, Rashi R, Junaid S, Khuroo MS, Farook S. Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) in Sinonasal Papillomas and Squamous Cell Carcinomas: A PCR-based Study of 60 cases. Gulf J Oncolog. 2018;1:37-42. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Hoffmann M, Klose N, Gottschlich S, Görögh T, Fazel A, Lohrey C, Rittgen W, Ambrosch P, Schwarz E, Kahn T. Detection of human papillomavirus DNA in benign and malignant sinonasal neoplasms. Cancer Lett. 2006;239:64-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hwang CS, Yang HS, Hong MK. Detection of human papillomavirus (HPV) in sinonasal inverted papillomas using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Am J Rhinol. 1998;12:363-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Govindaraj S, Wang H. Does human papilloma virus play a role in sinonasal inverted papilloma? Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;22:47-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hu H, Jiang H, Zhu Z, Yin H, Liu K, Chen L, Zhao M, Yu Z. Analysis of the anatomical distribution of HPV genotypes in head and neck squamous papillomas. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0290004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/