Published online Dec 16, 2025. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v17.i12.110842

Revised: August 29, 2025

Accepted: October 28, 2025

Published online: December 16, 2025

Processing time: 181 Days and 21.5 Hours

Dysphagia requires prompt evaluation but data regarding referral-to-assessment intervals and its association with outcomes in tertiary care are scarce, especially in Saudi Arabia.

To investigate the assessment and outcome of consecutive dysphagia referrals to a tertiary gastroenterology practice.

This retrospective single-center study analyzed 207 consecutive dysphagia re

Total 168 patients included in this study (mean age 45.7 ± 17.7 years, 50% male), referral delays > 2 weeks occurred in 44% for clinical assessment and 50% for endoscopy. Gastroesophageal reflux disease was most common (45.2%), followed by eosinophilic esophagitis (14.8%) and malignancy (6.5%). Patients receiving endoscopy within 2 weeks showed an 84.6% improvement, compared to 76.0% with delayed referral (P = 0.012). All malignant cases were referred within 2 weeks, compared to 52.7% of non-malignant cases (P = 0.013). However, 67% of the malignant cases worsened, and 33% died.

Early endoscopy within 2 weeks provides significant benefit. Optimised management of dysphagia should consist of more direct referral pathways.

Core Tip: This is a retrospective analysis of 168 dysphagia patients, which shows that delays > 2 weeks are common (44%-50%), but early endoscopy significantly improves outcomes (84.6% vs 76.0% improvement, P = 0.012). Despite prioritised referral of malignant cases, the prognosis was dismal which underscores the importance of earlier patient presentation. Direct endoscopy within 2 weeks, mainly prioritising streamlined pathways for alarm features, could be a more cost-effective approach in management and can lead to better survival rates.

- Citation: AlQahtani KM, AlNasser AA, AlQahtani AM, AlTurki AA, Aljaili AK, Alamri AH, Owayed AS, Asiri YW, Bakkari SA, Jaddoh AM, Aldarsouny TA, Semaan TG, Elbayoumy MS, Alruzug IM, Alenezi AA, Bin-Ofaysan MS, Alsager MO, Alshahrani HS, Alhaddad SM, Almuhayzi HN, Almousa RA, Shehada AJ, AlMasri AA, Aldaher MK, Maaly ME, Hafez IM, Alzubide SR. Impact of referral delays on dysphagia outcomes in a Saudi tertiary center. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2025; 17(12): 110842

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v17/i12/110842.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v17.i12.110842

Most gastroenterology care requires referral. Dysphagia is a condition affecting approximately 3% of adults[1]. Oropharyngeal dysphagia defined as abnormality in initiating swallowing and coordinating the movement of solids and liquid from mouth to pharynx whereas the difficulty of swallowing from pharynx to gastroesophageal junction is esophageal dysphagia[2,3]. Timely access and assessment are associated with improved disease outcomes and patient satisfaction[4].

Dysphagia indicates a need for referral to gastroenterology care[5]. Multiple etiologies of dysphagia range from structural, inflammatory, and motility, with the most concerning being malignant neoplasm. However, the most common causes are benign in origin[6,7]. However, even in these situations, complication of weight loss and malnutrition persists[8].

Dysphagia is a prevalent presentation to Saudi tertiary centers, but little is known about local referral patterns and their impact on clinical outcomes. A lack of understanding on this issue makes it hard to know if current referral timings enable timely diagnosis and appropriate management. When it comes to a complete assessment of dysphagia, advanced diagnostic modalities are necessary. The diagnostic work-up of dysphagia usually involves a combination of endoscopy, esophageal manometry, barium swallow studies and/or computerized tomography[9]. Chicago classification criteria define achalasia subtypes as type I (absent peristalsis with minimal pressurization), type II (absent peristalsis with panesophageal pressurization), and type III (absent peristalsis with spastic contractions) and essentially rely on high-resolution manometry to confirm achalasia diagnosis and distinguish others motility disorders[5]. The pH-impedance may be used to identify the concomitant gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Systematic endoscopic assessment allows for proper grading of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) severity using Los Angeles (LA) classification as follows: (1) Grade A (mucosal breaks < 5 mm); (2) Grade B (5-10 mm); (3) Grade C (> 10 mm, < 75% circumference); and (4) Grade D (> 75% circumference).

Clinical guidelines vary significantly in their recommendations regarding when an investigation should be conducted following dysphagia referrals. The British Society of Gastroenterology’s guidelines recommend urgent upper endoscopy within two weeks for all dysphagia patients[5], while Canadian consensus guidelines suggest endoscopy within two months for non-urgent cases while reserving expedited evaluation for severe or rapidly progressive dysphagia[10]. However, both recommendations are based on limited evidence.

This study aims to: (1) Audit adherence to international consensus guidelines and identify adverse outcomes related to delays; and (2) Determine whether referral processes can be improved to identify patients requiring expedited access. Our overall goal is to retrospectively analyze dysphagia management in our tertiary center, specifically evaluating the impact of referral timelines on diagnostic and clinical outcomes.

This retrospective single-center study was conducted at King Saud Medical City, a tertiary referral center in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, over 2 years (2022-2023).

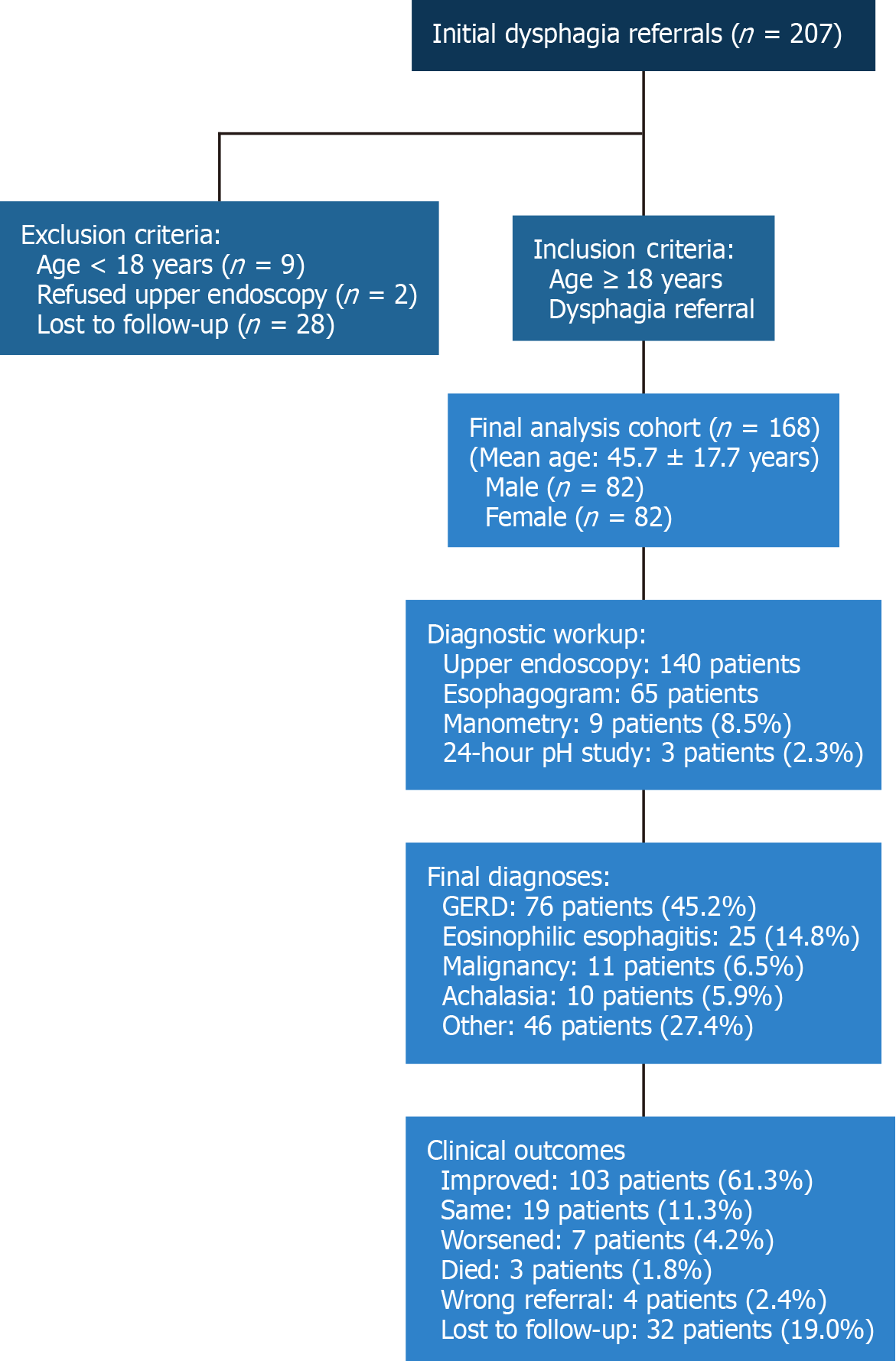

Total 207 consecutive dysphagia referrals were identified through Tanseeq and Watheeq electronic referral systems. A patient flow chart summarizing selection criteria and exclusions is presented in Figure 1. Chart reviews were performed for all referrals, identifying: (1) The patient’s age, biological sex; (2) Previously identified etiology of dysphagia; (3) Medications that may impact dysphagia (opioids, benzodiazepines, antiepileptic drugs, and antipsychotics); (4) Pre

All patients aged 18 years or older referred for dysphagia were included. Patients aged < 18 years (n = 9), or who did not attend their endoscopy appointment, refused upper endoscopy (n = 2), or were lost to follow-up without a final diagnosis (n = 28), were excluded. Charts were reviewed based on the patient's medical record number (MR). All patients were given a study number that corresponds to the MR number. This information was stored in a separate encrypted file. All data were collected into a database that only identified patients by study number. This database did not contain any personal identifiers and was stored on an encrypted, password-protected memory storage device after analysis was complete to ensure confidentiality. Data in these computerized files was encrypted, and the encryption key was kept by the principal investigator. The study data were available only to the research team. Participants were not identified in any publication or reports.

Dysphagia classification: Oropharyngeal dysphagia was diagnosed based on clinical presentation, swallowing evaluation, and neurological assessment. Esophageal dysphagia was confirmed by endoscopy, imaging studies, and manometry when indicated.

GERD severity assessment: GERD diagnosis was based on the endoscopist's final clinical impression of LA classification.

Achalasia classification: When high-resolution manometry was available, achalasia was classified according to Chicago classification criteria into types I, II, and III based on peristaltic patterns and pressurization characteristics. Due to this limitation, achalasia was diagnosed based on clinical symptoms and barium swallow.

Manometry and 24-hour pH: Due to the newly established nature of our motility unit during the study period, studies were performed selectively, based on equipment availability and clinical indications, during our unit's development phase. Patient improvement was assessed based on subjective symptom improvement reported at follow-up visits, reflecting real-world clinical practice patterns.

The study was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Board at King Saud Medical City (No. H1RI-03-Jun24-01). Patient confidentiality and anonymity were maintained throughout the process.

Data were entered and analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 28.0. Descriptive statistics included frequencies and percentages for categorical variables; as well as means, ranges, and SD for continuous numerical variables. The χ2 or Fisher's exact test was used to assess associations between categorical variables. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used to compare means of a continuous variable between groups, while post-hoc Tukey test was used in case of significant ANOVA to compare between individual groups. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. An audit was conducted to assess how well the local metrics align with international consensus guidelines, e.g., Canadian[10], British[5], and United States[11] recommendations.

A total of 168 patients were included in the study following the patient flow outlined in Figure 1. Their baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The study population was equally distributed by gender (82 males, 82 females), with ages ranging from 18 years to 87 years (mean 45.7 ± 17.7 years). Most patients were referred by the family medicine department (69.4%). Previous dysphagia etiology was reported in 9.9% of patients; mainly corrosive/caustic ingestion, esophageal cancer, and central nervous system glitches (21.4% for each). Dysphagia duration ≥ 4 weeks occurred in 44.5% of cases. Progressive dysphagia was present in 48.5% of patients. Two-thirds (66.7%) experienced retrosternal (mid-chest) dysphagia, while one-third (33.3%) experienced cervical (neck-level) dysphagia. Associated symptoms included heartburn (64.6%), regurgitation (58.0%), weight loss (42.2%), chest pain (35.9%), and globus sensation (23.4%).

| Baseline characteristics | Total study population (n = 168) | Early endoscopy (< 2 weeks) (n = 36) | Delayed endoscopy (≥ 2 weeks) (n = 45) | P value |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 45.7 ± 17.7 | 48.0 ± 17.7 | 44.2 ± 16.7 | 0.365 |

| Male gender | 82 (50.0) | 19 (52.8) | 18 (40.0) | 0.356 |

| Referral source | ||||

| Family medicine | 116 (69.4) | 19 (52.8) | 38 (84.4) | 0.004 |

| Emergency department | 19 (11.4) | 7 (19.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.002 |

| General surgery | 12 (7.2) | 5 (13.9) | 1 (2.2) | 0.083 |

| Otorhinolaryngology | 7 (4.2) | 2 (5.6) | 3 (6.7) | 1 |

| Oncology | 6 (3.6) | 1 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.444 |

| Infectious diseases | 2 (1.2) | 1 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.444 |

| Clinical features | ||||

| Duration ≥ 4 weeks | 57 (44.5) | 18 (50.0) | 22 (48.9) | 1 |

| Progressive dysphagia | 64 (48.5) | 15 (41.7) | 19 (42.2) | 1 |

| Retrosternal location | 86 (66.7) | 28 (84.8) | 25 (58.1) | 0.024 |

| Weight loss | 54 (42.2) | 14 (38.9) | 20 (44.4) | 0.782 |

| Heartburn | 84 (64.6) | 23 (63.9) | 29 (64.4) | 1 |

| Regurgitation | 76 (58.0) | 21 (58.3) | 25 (55.6) | 0.98 |

| Chest pain | 47 (35.9) | 12 (33.3) | 16 (35.6) | 1 |

| Globus sensation | 30 (23.4) | 3 (8.3) | 6 (13.3) | 0.724 |

| Diagnostic workup | ||||

| Manometry performed | 9 (8.5)1 | 3 (8.3) | 4 (8.9) | 1 |

| 24-hour pH study | 3 (2.3)1 | 1 (2.8) | 1 (2.2) | 1 |

| Esophagogram performed | 65 (38.7) | 12 (33.3) | 18 (40.0) | 0.647 |

| Final diagnoses | ||||

| GERD | 76 (45.2) | 14 (38.9) | 20 (44.4) | 0.782 |

| Eosinophilic esophagitis | 25 (14.8) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (13.3) | 0.031 |

| Complicated GERD with stricture | 9 (5.4) | 8 (22.2) | 1 (2.2) | 0.009 |

| Malignancy | 11 (6.5) | 1 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.444 |

| Achalasia | 10 (5.9) | 1 (2.8) | 5 (11.1) | 0.219 |

| Other diagnoses | 37 (22.0) | 12 (33.3) | 13 (28.9) | 0.809 |

| Clinical outcomes | ||||

| Improved outcome | 103 (61.3) | 23 (63.9) | 27 (60.0) | 0.898 |

Referral delays exceeded two weeks across multiple care stages. Time from primary referral to clinical assessment by the gastroenterology department exceeded two weeks in 44% of patients, while referral to endoscopy exceeded two weeks in 50% of cases. Additionally, the time from primary site referral to undergoing esophagogram exceeded two weeks in 50.8% of patients. Between clinical assessment and endoscopy, delays exceeded two weeks in 27.2% of patients, while delays between clinical evaluation and performance of esophagogram exceeded two weeks in 43.7% of patients.

Advanced diagnostic testing was limited during the establishment phase of our unit. Manometry was performed in 9 patients (8.5% of 106 evaluated), while 24-hour pH studies were conducted in 3 patients (2.3%). Most endoscopic biopsies were obtained from the distal esophagus (61.5%), followed by the proximal esophagus. Among patients who underwent endoscopic evaluation, LA classification revealed grade A esophagitis in 3 patients (3.9%), grade B in 55 patients (72.4%), grade C in 9 patients (11.8%), and grade D in 9 patients (11.8%), with grade B representing the majority of cases (72.4%).

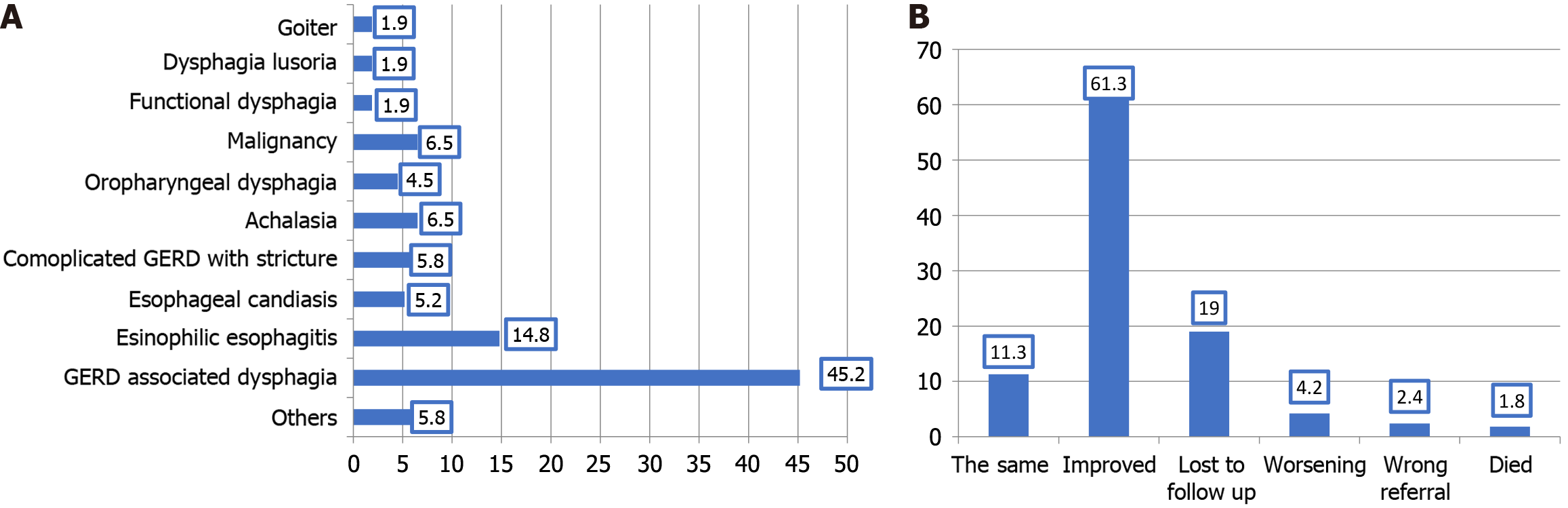

GERD was the most common condition (45.2%), followed by eosinophilic esophagitis (14.8%), while malignancy was reported in 6.5% of cases (Figure 2A). Significant gender differences were observed: Eosinophilic esophagitis was more prevalent in males (23.4% vs 6.7%, P = 0.004), while GERD showed a female predominance trend (53.3% vs 39.0%, P = 0.076). Age distributions varied significantly by etiology (P < 0.001). Malignancy patients were older (63.8 ± 15.1 years) compared to eosinophilic esophagitis patients (33.7 ± 9.7 years, P < 0.001). Age of patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia was also significantly higher than those with eosinophilic oesophagitis (57.4 ± 21.5 vs 33.7 ± 9.7), P = 0.033.

Most dysphagia patients (61.3%) improved after management, while 4.2% worsened and 1.8% died (Figure 2B). Early endoscopy significantly improved outcomes, as 84.6% of patients receiving endoscopy within two weeks showed improvement, compared to 76.0% with delays exceeding four weeks (P = 0.012) (Table 2).

| Final outcome | P value1 | |||||

| The same (n = 19) | Improved (n = 103) | Worsening (n = 7) | Wrong referral (n = 4) | Died (n = 3) | ||

| Time of referral to clinical assessment by gastroenterology department in weeks (n = 133) | n = 18 | n = 0 | n = 0 | n = 3 | n = 2 | |

| ≤ 2 hours (n = 72) | 6 (8.3) | 57 (79.2) | 6 (8.3) | 1 (1.4) | 2 (2.8) | |

| 3-hour (n = 22) | 4 (18.2) | 18 (81.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| > 4 hours (n = 39) | 8 (20.5) | 28 (71.8) | 1 (2.6) | 2 (5.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.246 |

| Time from referral to endoscopy in weeks (n = 132) | n = 18 | n = 0 | n = 0 | n = 3 | n = 1 | |

| ≤ 2 hours (n = 65) | 3 (4.6) | 55 (84.6) | 6 (9.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.5) | |

| 3-hour (n = 17) | 6 (35.3) | 10 (58.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| > 4 hours (n = 50) | 9 (18.0) | 38 (76.0) | 1 (2.0) | 2 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.012 |

| Time from referral to esophagogram in weeks (n = 60) | n = 11 | n = 47 | n = 0 | n = 2 | n = 0 | |

| ≤ 2 hours (n = 30) | 3 (10.0) | 26 (86.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 3-hour (n = 6) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| > 4 hours (n = 24) | 5 (20.8) | 18 (75.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.226 |

| Time from clinical assessment to endoscopy in weeks (n = 129) | n = 18 | n = 100 | n = 7 | n = 3 | n = 1 | |

| ≤ 2 hours (n = 95) | 9 (9.5) | 77 (81.1) | 6 (6.3) | 2 (2.1) | 1 (1.1) | |

| 3-hour (n = 14) | 6 (42.9) | 6 (42.9) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| > 4 hours (n = 20) | 3 (15.0) | 17 (85.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.046 |

| Time from clinical assessment to esophagogram in weeks (n = 50) | n = 10 | n = 39 | n = 0 | n = 1 | n = 0 | |

| ≤ 2 hours (n = 29) | 3 (10.3) | 26 (89.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 3-hour (n = 8) | 4 (50.0) | 4 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| > 4 hours (n = 13) | 3 (23.1) | 9 (69.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.054 |

All malignant cases received expedited referrals within two weeks (100% vs 52.7% non-malignant, P = 0.013). Despite rapid referral, prognosis remained poor: 67% of malignant cases worsened, and 33% died compared to 2.3% worsening and 0.8% mortality in non-malignant cases (P < 0.001) (Table 3).

| Non-malignant cases (n = 128) | Malignant cases (n = 6) | P value1 | |

| The same (n = 19) | 19 (14.8) | 0 (0.0) | < 0.001 |

| Improved (n = 101) | 101 (79.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Worsening (n = 7) | 2 (2.3) | 4 (66.7) | |

| Wrong referral (n = 4) | 4 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Died (n = 3) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (100) |

The impact of the time from referral to clinical assessment in gastroenterology, on diagnose and prognosis of patients with dysphagia was not investigated extensively. Thus, this study is a trial to investigate this issue in a highly qualified center in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

In the current study, the most frequently reported cause of dysphagia was GERD (45.2%), followed by esinophilic esophagitis (14.8%) whereas malignancy was reported in 6.5% of cases. Also, GERD was the most common cause of dysphagia reported among United States patients[11]. It has been reported that esophageal dysphagia is commonly caused by GERD and functional esophageal disorders, while eosinophilic esophagitis is triggered by food allergens; it has also been recommended that esophageal biopsies be done to ensure the diagnosis is accurate[12].

Our study demonstrates benefits of expedited endoscopy in the management of dysphagia. Of the patients receiving endoscopy within two weeks, 84.6% showed improved outcomes compared to 76.0% with delayed referral (P = 0.012). Our analysis reveals patterns in referral prioritization – specifically, emergency department referrals consistently received expedited endoscopy within two weeks (19.4% vs 0%, P = 0.002), whereas family medicine referrals were more likely to experience delays (84.4% vs 52.8% in the delayed group, P = 0.004). Notably, patients with retrosternal dysphagia were more likely to receive early endoscopy (84.8% vs 58.1%, P = 0.024), and complicated GERD cases were appropriately prioritized for evaluation (22.2% vs 2.2% in the early group, P = 0.009).

In this study, 44% of patients with dysphagia experienced a referral time of more than two weeks from the primary site to clinical assessment by the gastroenterology department, while Canadian guidelines recommend endoscopy within two months for non-severe dysphagia[10], and British guidelines advocate urgent endoscopy within two weeks for all dysphagia cases[5]. Our findings highlight discrepancies in meeting international benchmarks, particularly for high-risk populations. Similarly, the referral time to endoscopy exceeded two weeks in 50% of cases, and the time to esophagogram performance exceeded two weeks in 50.8% of cases. Additionally, the time between clinical assessment and endoscopy exceeded two weeks for 27.2% of patients, while the time between clinical evaluation and esophagogram performance exceeded two weeks for 43.7% of patients. Current guidelines recommend esophagogastroduodenoscopy to exclude esophageal etiologies in patients presenting with dysphagia[13]. Supporting this approach, Waters et al[14] recently emphasized that adults with new-onset dysphagia require urgent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy within two weeks to facilitate timely diagnosis and management.

This study revealed that 61.3% of the patients with dysphagia improved after management while minority (4.2%) got worse and 1.8% died. Many factors could impact the prognosis of cases of dysphagia; among these factors the etiology of dysphagia and the time of referral[15]. In the present study, most cases referred from the primary department of presentation or from clinical assessment to endoscopy performance in a short period (within two weeks) was associated with better outcome of management compared to those who referred later. This finding supports the importance of early referral of cases of dysphagia for further care on the disease prognosis.

This study showed that all malignant cases were referred to clinical assessment by gastroenterology department and then to endoscopy performance within two weeks. Despite of that, two-thirds of malignant cases got worse after management and the remaining third died. It has been documented that despite advances in diagnosis and therapy, the prognosis of malignant cases presented with dysphagia remains poor, with a less than 20% 5-year survival rate[16]. Furthermore, Allum et al[17] reported that 50% of malignant cases of dysphagia had either a locally advanced disease or distant metastasis on presentation, which negatively impacts long-term remission and cure rates.

In the present study, GERD was reported as a cause of dysphagia more in female patients than male patients; however, the difference did not reach a statistically significant level. In earlier studies conducted in Germany[18] and Australia[19], no gender difference was observed. However, the male predominance in eosinophilic esophagitis (23.4% vs 6.7% in females, P = 0.004) aligns with the international literature[20]. Interestingly, eosinophilic esophagitis was significantly more common in the delayed endoscopy group (13.3% vs 0%, P = 0.031), suggesting potential diagnostic opportunities with earlier evaluation.

In the present study, history of performing manometry or 24 hours pH study was found in only 8.5% and 2.3% of patients presented with dysphagia, respectively due to equipment limitations during the unit’s development. This represents both a limitation and real-world challenges faced by developing healthcare units. The British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines recommended performing high-resolution manometry when investigating dysphagia cases, particularly those with achalasia, as well as pH studies for patients with symptoms of GERD, patients not responding to high-dose proton pump inhibitors, and patients with symptoms of GERD responsive to proton pump inhibitors for whom surgery is planned[5].

Low public awareness of dysphagia as a symptom of malignancy in Saudi Arabia may contribute to delayed patient presentation. Early detection improves survival and reduces healthcare costs[21,22].

In Saudi Arabia, integrating dysphagia awareness into national non-communicable disease screening programs – alongside diabetes or hypertension screenings, for example – could enhance early diagnosis and align with vision 2030 goals for preventive healthcare[23]. Our findings support advocating for: (1) Standardized referral protocols prioritizing endoscopy within two weeks; (2) Streamlined pathways for patients with alarm features; (3) The enhanced utilization of advanced diagnostic modalities as equipment becomes available; and (4) Systematic follow-up protocols.

Some noteworthy limitations of the present study should be acknowledged. First our study was conducted during the establishment phase of our motility unit. Outcome assessments relied on subjective patient-reported symptom impro

Furthermore, comparative studies are rare, which may affect the quality of our discussion of the results. Despite these limitations, the present study is unique in our region, utilized an adequate sample size, and includes a comprehensive description of different referral times for patients presenting with dysphagia, which could be of use to practitioners. While our study evaluated institutional referral timelines, we did not assess the duration between symptom onset and initial patient consultation, which may further explain the poor outcomes in malignancies. Finally, the absence of patient-reported symptom onset timing and delay causes represents a limitation. Future studies should incorporate patient-reported delays to better explain barriers to early presentation.

In conclusion, the referral and diagnostic process for dysphagia often exceeded two weeks in multiple stages, including referral to clinical assessment, endoscopy, and esophagogram. Nearly a quarter of patients faced delays of over two weeks between clinical assessment and endoscopy. The most frequently reported cause of dysphagia was GERD.

All malignant cases were referred from the primary department of presentation to clinical assessment by gastroenterology department and then to endoscopy performance within two weeks. Despite of that, prognosis was poor. Suggesting this is due to advanced stage rather than due to timing of referral. Based on these results, we recommend enhancing referral of patients presented with dysphagia directly to endoscopy to improve the prognosis. Further longitudinal multicentric study is warranted to give a comprehensive clear image of the situation in our community.

Implementation of detailed endoscopic grading systems and achalasia subtype classification would enhance diagnostic precision. Measuring patient-reported outcomes using validated score would strengthen assessment methodology.

We are grateful to the patients and their families for their support of the study.

| 1. | Cho SY, Choung RS, Saito YA, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Locke GR 3rd, Talley NJ. Prevalence and risk factors for dysphagia: a USA community study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:212-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Malagelada JR, Bazzoli F, Boeckxstaens G, De Looze D, Fried M, Kahrilas P, Lindberg G, Malfertheiner P, Salis G, Sharma P, Sifrim D, Vakil N, Le Mair A. World gastroenterology organisation global guidelines: dysphagia--global guidelines and cascades update September 2014. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49:370-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cockeram AW. Canadian Association of Gastroenterology Practice Guidelines: evaluation of dysphagia. Can J Gastroenterol. 1998;12:409-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ferreira DC, Vieira I, Pedro MI, Caldas P, Varela M. Patient Satisfaction with Healthcare Services and the Techniques Used for its Assessment: A Systematic Literature Review and a Bibliometric Analysis. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;11:639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Trudgill NJ, Sifrim D, Sweis R, Fullard M, Basu K, McCord M, Booth M, Hayman J, Boeckxstaens G, Johnston BT, Ager N, De Caestecker J. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines for oesophageal manometry and oesophageal reflux monitoring. Gut. 2019;68:1731-1750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bill J, Rajagopal S, Kushnir V, Gyawali CP. Diagnostic yield in the evaluation of dysphagia: experience at a single tertiary care center. Dis Esophagus. 2018;31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kidambi T, Toto E, Ho N, Taft T, Hirano I. Temporal trends in the relative prevalence of dysphagia etiologies from 1999-2009. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4335-4341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Khan MQ, AlQaraawi A, Al-Sohaibani F, Al-Kahtani K, Al-Ashgar HI. Clinical, endoscopic, and radiologic features of three subtypes of achalasia, classified using high-resolution manometry. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:152-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Leslie P, Carding PN, Wilson JA. Investigation and management of chronic dysphagia. BMJ. 2003;326:433-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Paterson WG, Depew WT, Paré P, Petrunia D, Switzer C, Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, Daniels S; Canadian Association of Gastroenterology Wait Time Consensus Group. Canadian consensus on medically acceptable wait times for digestive health care. Can J Gastroenterol. 2006;20:411-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R; Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900-1920; quiz 1943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2368] [Cited by in RCA: 2523] [Article Influence: 126.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 12. | Wilkinson JM, Codipilly DC, Wilfahrt RP. Dysphagia: Evaluation and Collaborative Management. Am Fam Physician. 2021;103:97-106. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Ashraf HH, Palmer J, Dalton HR, Waters C, Luff T, Strugnell M, Murray IA. Can patients determine the level of their dysphagia? World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:1038-1043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Waters AM, Patterson J, Bhat P; r,, Phillips AW. Investigating dysphagia in adults: symptoms and tests. BMJ. 2022;379:e067347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Triggs J, Pandolfino J. Recent advances in dysphagia management. F1000Res. 2019;8:F1000 Faculty Rev-F1000 Faculty1527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kauppila JH, Mattsson F, Brusselaers N, Lagergren J. Prognosis of oesophageal adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma following surgery and no surgery in a nationwide Swedish cohort study. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e021495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Allum WH, Blazeby JM, Griffin SM, Cunningham D, Jankowski JA, Wong R; Association of Upper Gastrointestinal Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland, the British Society of Gastroenterology and the British Association of Surgical Oncology. Guidelines for the management of oesophageal and gastric cancer. Gut. 2011;60:1449-1472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 460] [Cited by in RCA: 425] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bollschweiler E, Knoppe K, Wolfgarten E, Hölscher AH. Prevalence of dysphagia in patients with gastroesophageal reflux in Germany. Dysphagia. 2008;23:172-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chen Z, Thompson SK, Jamieson GG, Devitt PG, Watson DI. Effect of sex on symptoms associated with gastroesophageal reflux. Arch Surg. 2011;146:1164-1169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Basavaraju KP, Wong T. Eosinophilic oesophagitis: a common cause of dysphagia in young adults? Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62:1096-1107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Pu D, Liu J, Yao TJ. Awareness of Dysphagia: An Integrative Review. Perspect ASHA Spec Interest Gr. 2025;10:974-990. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 22. | Tran CL, Han M, Kim B, Park EY, Kim YI, Oh JK. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and risk of cancer: Findings from the Korean National Health Screening Cohort. Cancer Med. 2023;12:19163-19173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hazazi A, Wilson A. Noncommunicable diseases and health system responses in Saudi Arabia: focus on policies and strategies. A qualitative study. Health Res Policy Syst. 2022;20:63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/