Published online Nov 16, 2025. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v17.i11.112519

Revised: August 30, 2025

Accepted: October 22, 2025

Published online: November 16, 2025

Processing time: 107 Days and 23.8 Hours

Congenital gastric ectopic pylorus (CGEP), also known as gastric ectopic pyloric opening, is a rare congenital gastric abnormality. It was first reported and termed by Yu and Zhao from China in 1983, and in 2007, Uraz et al published the first report of CGEP in the English literature. We conducted a systemic review of the literature of CGEP published in English or Chinese, and found that CGEP occu

Core Tip: Congenital gastric ectopic pylorus is an extremely rare congenital gastrointestinal anomaly characterized by an abnormal pyloric opening location. To date, only a few cases have been reported. This is the first review of congenital gastric ectopic pylorus regarding its history, etiology, diagnosis, and treatment, aiming to facilitate a better understanding of this rare condition.

- Citation: Wang C, Wang CH, Shi WJ, Pan SW, Zhai YQ. Brief overview of congenital gastric ectopic pylorus: A rare gastric abnormality. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2025; 17(11): 112519

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v17/i11/112519.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v17.i11.112519

Congenital gastric ectopic pylorus (CGEP), also known as gastric ectopic pyloric opening, is a rare congenital gastric abnormality[1,2]. Most patients present with abdominal pain, bloating, regurgitation, and belching, while some patients (31%) may present with upper gastrointestinal bleeding, such as hematemesis and melena[3-6]. Gastroscopy and upper gastrointestinal radiography are the main methods used to confirm the diagnosis, and conservative medication is accepted as the mainstay treatment[4-6]. However, in clinical practice, misdiagnosis and underdiagnosis often occur due to the non-specific symptoms in CGEP patients. In addition, the etiology of this disease and its potential association with malignancies remain unknown.

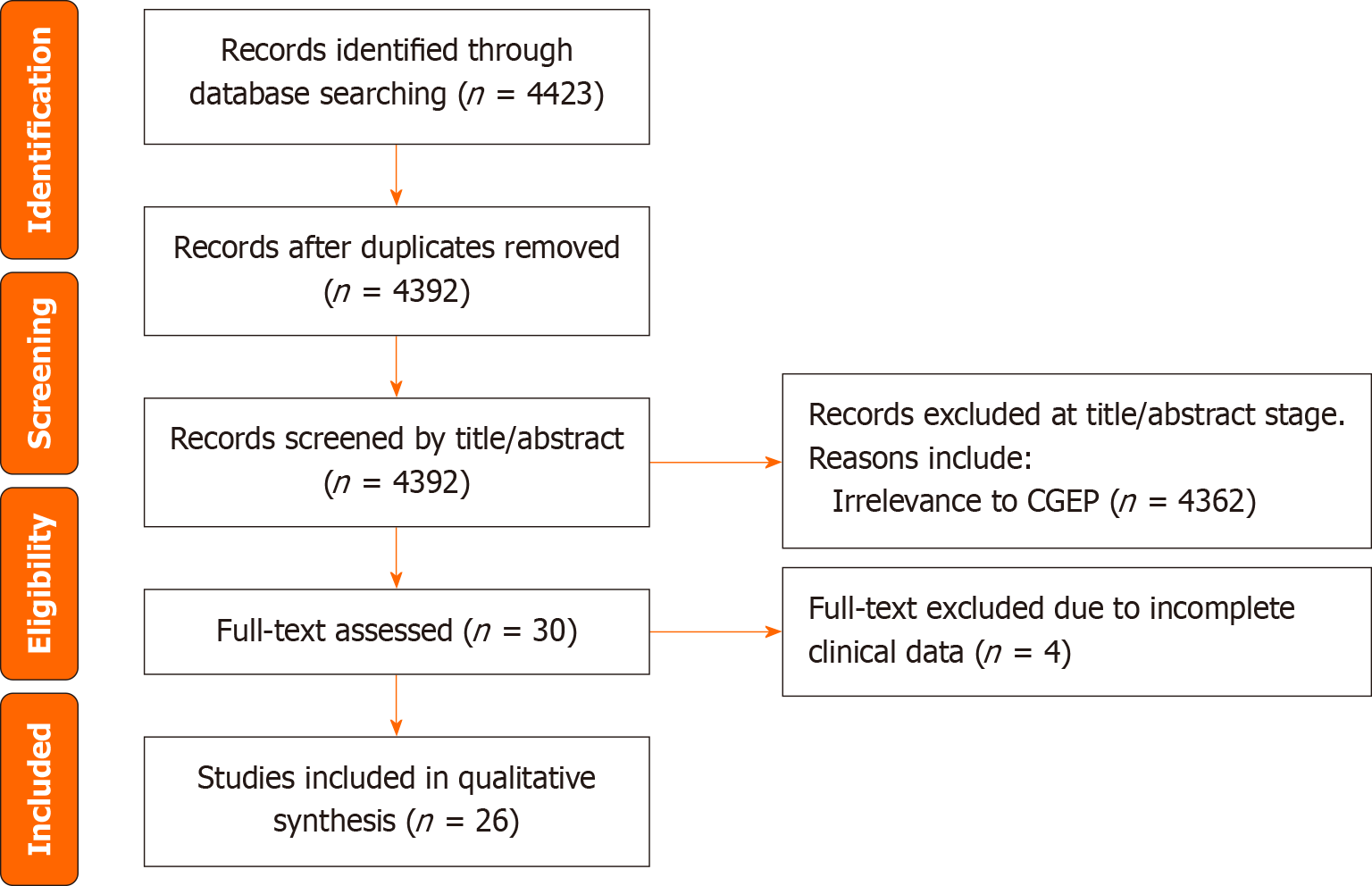

Therefore, we conducted a comprehensive literature search of several databases both in English and Chinese. In this systematic review, we describe the history, epidemiology, etiology, diagnosis and treatment of CGEP in detail, aiming to provide a comprehensive understanding of this rare disease.

Several electronic databases were searched, including PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, China Biology Medicine disc, and Wanfang database, with the search period spanning from database inception to November 2024. The literature search was conducted by an experienced medical librarian, using the input from the study authors.

Keywords used in the search included a combination of “pylor”, “ectopi”, “heterotopi”, “abnormality”, “malf

| Features | Variables |

| Total number | 29 |

| Age (range), years | 59.6 ± 11.6 (37-73) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 26 (89.7) |

| Female | 3 (10.3) |

| Clinical manifestation | |

| Abdominal pain | 19 (65.5) |

| Abdominal distension | 12 (41.4) |

| Acid regurgitation | 9 (31.0) |

| Belching | 7 (24.1) |

| Vomiting | 9 (31.0) |

| Bleeding | 9 (31.0) |

| Opening position | |

| Lesser curvature of gastric body | 17 (58.6) |

| Gastric angle | 10 (34.5) |

| Gastric antrum | 1 (3.4) |

| Posterior wall of gastric body | 1 (3.4) |

| Complications | |

| Gastric erosion or ulcer | 21 (72.4) |

| Atrophic gastritis | 11 (37.9) |

| Gastric cancer | 2 (6.9) |

| Treatment | |

| Medication | 29 (100) |

Quality assessment of included case reports was performed using the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for case reports, which evaluates 8 domains including clear identification of the patient, adequacy of clinical information, description of intervention and outcomes. Two reviewers (Wang C and Zhai YQ) independently assessed each study, with discrepancies resolved by consensus. All included studies met at least 6 of the 8 quality criteria.

CGEP refers to the abnormal positioning of the pyloric opening, which is typically located in the gastric angle or body rather than its normal anatomical site - the junction of the gastric antrum and duodenum. As the narrowest segment of the stomach, the pylorus plays a critical role in regulating the passage of food into the small intestine; thus, any anatomical abnormalities in its position can lead to various digestive complications.

In 1983, Chinese scholars Yu and Zhao[7] first reported the case of a 58-year-old male with an ectopic pyloric opening located at the gastric angle. The patient underwent gastroscopy due to upper abdominal pain accompanied by abdominal distension and belching, which revealed a pouch-like structure in the antrum with no visible pyloric orifice. Upon upward rotation of the endoscope, the pyloric opening was identified at the gastric angle, accompanied by reflux of yellow foamy intestinal fluid. Owing to the technical limitations of equipment at that time, the authors attempted repeatedly to pass a fiberoptic gastroscope through the ectopic opening, but without success. However, the reflux fluid was aspirated and confirmed to be alkaline duodenal fluid (pH = 8). Based on the findings of upper gastrointestinal radiography, clinical history, and clinical manifestations, the condition was termed CGEP. Since then, over 15 newly identified cases have been reported across various regions in China.

In 2007, Uraz et al[1] from Turkey published the first English-language report of a CGEP case. A 60-year-old male patient presented with postprandial epigastric discomfort. Gastroscopy revealed that the gastric outlet was located at the angular notch rather than the normal position. Given the absence of a surgical or ulcer history, the condition was deemed congenital.

Systematic literature searches show that the condition has been referred to by various terms, including “congenital gastric ectopic pylorus”, “pyloric malformation”, “gastric outlet deformity”, and “congenital high-position pylorus”, with “congenital gastric ectopic pylorus” being the most commonly used. To facilitate academic communication, we propose the term “congenital gastric ectopic pylorus (CGEP)” as the unified nomenclature for this condition.

CGEP is an extremely rare disease, with majority of patients being male; and congenital anomaly typically occurs in individuals aged 50-70 years. Among these reported cases, East Asian patients account for 89.7%. The significant gender and regional disparities suggest that the disease may be associated with ethnicity and heredity. We are currently conducting high-throughput sequencing, which may help clarify the underlying cause.

The pathogenesis of CGEP remains unclear, but it is hypothesized to be related to developmental anomalies of the embryonic foregut. The human gastrointestinal tract develops from the embryonic endoderm and initially forms the primitive gut, which is divided into the foregut, midgut, and hindgut. During the fourth week of embryonic develo

Zhang et al[28] suggested that this condition might result from disproportionate development between the greater and lesser curvatures of the stomach during embryogenesis. Specifically, delayed development of the lesser curvature or accelerated development of the greater curvature could cause the pylorus to migrate upward, leading to high-position deformity.

CGEP may be asymptomatic. In cases of partial gastric outlet obstruction, symptoms may not appear until childhood or even adulthood. The delayed onset of clinical manifestations of this anomaly remains unknown, but progressive loss of compensatory peristaltic action to overcome the pyloric or duodenal narrowing is one of the suggested reasons[2].

The clinical symptoms of CGEP are mostly non-specific, making timely diagnosis challenging. Common symptoms include abdominal pain (66%), bloating (41%), acid regurgitation (31%), vomiting (31%) and belching (24%). These symptoms are primarily associated with the higher position of the ectopic pyloric opening, food retention, and gastric emptying disorders. The abnormal positioning of the pylorus disrupts its structural and functional integrity, leading to motility disorders and sphincter dysfunction[16]. These abnormalities can cause duodenal contents to reflux into the stomach, resulting in gastric mucosal damage, gastritis, and mucosal erosion[3]. Chronic exposure to digestive enzymes and bile acids further increases the risk of gastric ulceration and other complications.

Our systematic literature review showed that 72.4% of patients with CGEP developed gastric erosion or ulcers, mainly localized near the ectopic pyloric opening[3-5,7,8,10,12,13,15,16,18-22,24-26]. Approximately 31% of patients experience hematemesis or melena, with 50% presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding as the initial symptom. The case we reported was complicated by multiple gastric ulcers and presented with gastrointestinal bleeding as the initial manifestation, prompting hospital admission for treatment[6]. Additionally, 37.9% of patients were diagnosed with coexisting atrophic gastritis, and 7% develop gastric cancer[4,20]. These findings suggest a potential association between CGEP, chronic inflammation, and malignancy. Factors such as prolonged gastric emptying disturbances, intragastric accumulation of dietary carcinogens, and chronic inflammatory stimulation may contribute to the development of atrophic gastritis and gastric cancer.

Gastroscopy is the gold standard for diagnosing CGEP. It allows direct visualization of gastric morphology, identification of the location of the pyloric opening, and detection of associated conditions such as ulcers or tumors[24]. Gastroscopy also aids in distinguishing CGEP from secondary pyloric displacement caused by scarring and contracture due to gastric ulcers. Additionally, endoscopic biopsy can assist in diagnosis and differential diagnosis.

Upper gastrointestinal radiography is also an important diagnostic tool, offering a simple and intuitive method for visualizing the morphology of the stomach and duodenum, confirming the location of the pyloric opening, and assessing gastric emptying[16,24]. In patients with CGEP, upper gastrointestinal radiography may show a shortened gastric axis, a blind-ended gastric antrum, and evidence of liquid retention during fasting. Due to the abnormal location of the pyloric opening, the stomach may take on distinctive shapes, such as a “teapot” or “hammer” shape[4,6].

Computed tomography provides high-resolution cross-sectional images that clearly depict the anatomy of the gastric pylorus, its position, and its relationship with surrounding structures. Such detailed anatomical information can aid in diagnosing CGEP. In addition, external gastric ultrasonography can also assist in diagnosing this condition. Ma SJ[26] has shown that ultrasound examination can visualize the evacuation of the pyloric orifice, meanwhile, it can clearly display lesions in the gastric wall and gastric cavity.

Conservative medical treatment is the preferred therapeutic approach for CGEP, with the focus on symptom management using acid suppressants, prokinetic agents, and gastric mucosal protectants[1,2,5,19,24]. Acid-suppressing medications, such as proton pump inhibitors and H2 receptor antagonists, can reduce gastric acid secretion and alleviate mucosal damage. Prokinetic agents, such as domperidone and mosapride, can enhance gastric motility and improve gastric emptying. Gastric mucosal protectants, such as sucralfate and colloidal bismuth, form a protective barrier over the gastric lining, preventing further injury. Pan[25] indicated that following the administration of rabeprazole (20 mg once daily) and mosapride (5 mg three times daily), the patient’s symptoms, including abdominal pain and bloating, gradually alleviated after 3 days and essentially resolved by 2 weeks. For patients with active peptic ulcer bleeding, endoscopic hemostasis is a viable option[19]. Additionally, lifestyle modifications, such as postprandial posture adjustments (lying flat or on the left side after meals), may help alleviate symptoms[11,22,24]. Although no surgical cases have been reported, surgical intervention may be considered for younger patients with recurrent symptoms unresponsive to medical therapy or individuals with complications such as pyloric stenosis.

This systematic review has certain limitations. First, the majority of included studies are individual case reports, which inherently limits the generalizability of our findings. Case reports often focus on unusual or severe presentations, potentially overrepresenting specific clinical features and leading to selection bias. Second, there is a risk of publication bias, as positive or more clinically significant cases may be more likely to be reported in the literature, while mild or asymptomatic cases might remain underreported. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the conclusions of this review, and future studies with larger sample sizes and standardized data collection are needed to validate our observations.

In summary, CGEP is a rare congenital gastric abnormality of unknown etiology, characterized by non-specific symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating, acid reflux, and belching. It predominantly affects elderly males and has an obvious racial predisposition. Gastroscopy remains the gold standard for diagnosis, and medical therapy is the first-line treatment. In addition, lifestyle modifications are also crucial. Eating less but frequent meals, lying flat or in a left lateral position after meals are suggested. This is because the ectopic pylorus is mostly located at the gastric angle and the lesser curvature of the gastric body; under the influence of gravity, gastric contents accumulate in the gastric body, enabling direct contact between the food and the ectopic pyloric orifice at the gastric angle or lesser curvature of the gastric body. Furthermore, the siphoning effect generated by the downward peristalsis of the small intestine greatly facilitates gastric emptying[22].

The ectopic pylorus raised the outflow tract and may result in food retention and mechanical stimulation, eventually leading to delayed gastric emptying, gastric discomfort, or gastric ulcer[5]. Among all ectopic pyloric orifice locations, those opening on the lesser curvature of the gastric body are associated with the greatest elevation of the gastric outflow tract. Given this anatomical characteristic, whether this specific ectopic location confers a higher risk of gastric ulcer development warrants further investigation. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) are closely related to chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer, and gastric cancer[29]. Delayed gastric emptying may worsen H. pylori infections and ulcer[4]. Therefore, when patients with CGEP are encountered, H. pylori infection must be tested and eradicated. This may potentially reduce the incidence of gastric ulcer or gastric cancer. The underlying mechanisms of these racial and gender predispositions, as well as the potential role of surgical interventions, warrant further investigation through large-scale studies. By consolidating existing knowledge and identifying research gaps, this review aims to facilitate a deeper understanding of CGEP and its clinical implications. Future research should focus on elucidating its embryological origins, exploring genetic and environmental determinants, and optimizing diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

| 1. | Uraz S, Aygün C, Konduk T, Celebi A, Sentürk O, Hülagü S. A rare gastric outlet anomaly: pyloric ostium on incissura angularis. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:1001-1003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Di Carlo I, Pulvirenti E, Toro A, Di Blasi M. Absence of pylorus: a rare gastric malformation. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:1224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Calhan T, Sahin A, Kahraman R, Batu A. Atypical placement of the pylorus: a rare congenital abnormality. Endoscopy. 2014;46 Suppl 1 UCTN:E302-E303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lu B, Yang L. Gastric ectopic pyloric opening: an unusual case. Surg Radiol Anat. 2019;41:1395-1398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Koh M, Jang JS. Gastric Ectopic Pyloric Opening with Gastric Ulcer: A Rare Case. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2022;79:126-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wang C, Pan S, Zhai Y. Congenital gastric ectopic pylorus: a rare gastric malformation. Endoscopy. 2024;56:E508-E509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yu ZL, Zhao ZY. [A case report of ectopic pylorus]. Shiyong Neike Zazhi. 1983;06:321. |

| 8. | Ma YP, Sun SQ, Yang Q. [A case report of gastric malformation]. Heilongjiang Yixue. 1989;04:55-56. |

| 9. | Wang JX, Jia X, Su ZX. [Congenital ectopic pylorus: a case report]. Shanxi Yiyao Zazhi. 1990;06:375. |

| 10. | Suo XY. [A case report of gastric malformation]. Qinghai Yiyao Zazhi. 1992;05:59 + 68. |

| 11. | Pan YF, Lin SR. [A Case of Pyloric Malformation]. Shanxi Huli Zazhi. 1995;02:91-92. |

| 12. | Qiao WC, Zhang ZR, Wang JH. [High opening deformity of gastric pylorus: a case report]. Zhonghua Xiaohuaneijing Zazhi. 1996;04:61. |

| 13. | Sun XP, Yan PH. [Congenital gastric malformation with ectopic pylorus: a case report]. Shiyong Fangshexue Zazhi. 1997;09:25. |

| 14. | Qiu XM, Zhang XQ, Xu XF. [Ectopic pylorus: a case report]. Zhonghua Xiaohuaneijing Zazhi. 1997;04:48. |

| 15. | Wang P, Sun AH. [Gastric pyloric malformation complicated with multiple ulcers: a case report]. Zhonghua Xiaohuaneijing Zazhi. 1997;02:45. |

| 16. | Wang JT, Xue MX, Huang XN, Zhang MJ. [Discussion on congenital displacement of gastric pylorus (a report of 3 cases)]. Zhonghua Xiaohuaneijing Zazhi. 1998;03:57. |

| 17. | Guo LH, Huang DX, Tong MH. [Gastropyloric malformation with absence of duodenal bulb]. Beijing Junqu Yiyao. 2001;06:432. |

| 18. | Zhang H, Zhou HQ, Guo SL. [Congenital ectopia of the pylorus with absence of duodenal bulb: a case report]. Zhongguo Linchuangyixueyingxiang Zazhi. 2001;05:361. |

| 19. | Wang JP, Xiong Y, Guo HJ. [Congenital gastric ectopic pylorus with multiple gastric ulcers and bleeding: a case report]. Zhonghua Xiaohuaneijing Zazhi. 2004;05:69. |

| 20. | Tian SJ. [Ectopic pylorus and duodenal bulb deletion with cardia cancer: a case report]. Zhonghua Xiaohuaneijing Zazhi. 2004;(03):38. |

| 21. | Dao YG, Yi GF, Liang B. [Congenital ectopic pyloric opening with duodenal bulbar ulcer: a case report]. Zhongguo Linchuangshiyong Yixue. 2008;2:3. |

| 22. | Gan WP, Huang ZY. [Congenital ectopic pylorus and duodenal dysplasia: a case report]. Xiandaixiaohua Ji Jieruzhenliao. 2010;15:264. |

| 23. | Huang YQ, Huang WJ, Zhang J. [One case: high position malformation of pylorus]. Shiyong Fangshexue Zazhi. 2011;27:1614. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 24. | Chen C, Zhang YH, Zhang Y. [Ectopic pylorus accompanied by gastrolithiasis and gastric ulcer bleeding: a case report]. Zhongguo Quanke Yixuxe. 2013;16:1681-1682. |

| 25. | Pan J. [Gastric ectopic pylorus: a report of 2 cases]. Qinghai Yiyao Zazhi. 2016;46:4. |

| 26. | Ma SJ. [Ultrasonography for the diagnosis of gastric ectopic pylorus: a case report]. Zhongguo Chaoshengyixue Zazhi. 2018;34:757. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 27. | de Santa Barbara P, van den Brink GR, Roberts DJ. Molecular etiology of gut malformations and diseases. Am J Med Genet. 2002;115:221-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Zhang MJ, Xu QR, Dai ZC, Xu DY, Wang JT, Zang NL. [X-ray diagnosis of high position malformation of pylorus (a report of 5 cases)]. Zhongguo Linchuangyixueyingxiang Zazhi. 2002;13:65-66. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 29. | Huang J. Analysis of the Relationship between Helicobacter pylori Infection and Diabetic Gastroparesis. Chin Med J (Engl). 2017;130:2680-2685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/