Published online Oct 16, 2025. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v17.i10.108729

Revised: June 18, 2025

Accepted: September 1, 2025

Published online: October 16, 2025

Processing time: 177 Days and 20 Hours

The question of whether a colonoscopist should evaluate anal diseases is relevant. Endoscopists need to be aware of the possibility of anal neoplasms during a colonoscopy, as they can be easily overlooked if not properly examined. Speci

To assess the results of anal examinations performed during routine colonoscopy and emphasize the importance of diagnosing anal neoplasms.

This was a retrospective study of 16836 patients who were screened by colono

Among the 22676 colonoscopies performed, 16836 patients were identified, and 88 lesions suspected of neoplasia (0.52%) were found. Among them, there were 23 cases of neoplasia (0.13%), 9 cases of confirmed squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal (0.05%), 5 cases of adenocarcinoma in the anal canal (0.03%), 3 cases of rare neoplasms (0.01%), and 6 cases of adenoma (0.03%).

The systematic performance of anal examinations and anoscopy during routine colonoscopy allows the identification of numerous anal diseases, including incidental cases of anal cancer.

Core Tip: Endoscopists have expressed concerns that the colonoscope does not provide an adequate view of the anal canal. The use of the anoscope and rectal retroflexion allows for perfect visualization of the anal canal. This approach has led to the diagnosis of important conditions through videoanoscopy. Although the incidence of squamous cell carcinoma is extremely low, the presence of several other benign and malignant lesions justifies routine examination of the anal region.

- Citation: Gomes A, Bara J, da Matta CHKT, Paiva PP, de Carvalho LM, Bononi BM, Pinto PCC, Rodrigues JMS, Borghesi RA. Anal neoplasm in colonoscopy: What endoscopists need to know. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2025; 17(10): 108729

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v17/i10/108729.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v17.i10.108729

It is common for clinicians and surgeons to refer patients with proctological complaints for colonoscopy as part of colorectal cancer screening. Nevertheless, some colonoscopists may not have sufficient training in coloproctology to perform this evaluation effectively and may argue that the colonoscope does not provide sufficient visibility of the anal canal. Nonetheless, routine anal examination should be conducted and can be performed effectively during colonoscopy[1-3]. Adequate evaluation of the anal canal and perianal region requires careful inspection, digital anorectal examination, and the use of an anoscope[4-6]. Anal cancer is rare, and a retrospective approach is commonly used to assess the characteristics of patients with this disease. Among all large intestinal tumors, the prevalence of malignant tumors of the anus and anal canal does not exceed 2%[7,8]. The National Cancer Institute of Brazil does not have data on anal cancer; however, the National Cancer Institute in the United States reported 10540 new cases (3360 in men and 7180 in women) and 2190 deaths (1000 in men and 1190 in women). According to a 2025 estimate by the American Cancer Society, 10930 new cases and 2030 deaths from the disease are expected to occur in 2025[8]. Anal cancer represents 0.3% of all cancer cases and accounts for 0.5% of all cancer-related deaths in the United States[7,8]. Attention to human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccination, as well as improving the awareness of sexually related risk factors, together with progress in diagnosis and management, are priority measures for anal cancer control worldwide[9].

Although the rate of progression from premalignant lesions to invasive carcinoma is low (2% to 9%) this rate is significantly higher (13% to 50%) in immunocompromised individuals. Consequently, population-based screening is not recommended; instead, the monitoring of high-risk groups is recommended. This disease has a low prevalence but high morbidity[10]. The rationale for follow-up is the excellent response of the disease to chemoradiotherapy. Nevertheless, advanced-stage disease necessitates abdominoperineal resection of the rectum, accompanied by dissection and inguinal lymphadenectomy, procedures associated with high morbidity and reduced quality of life. The clinical presentation of anal cancer encompasses a wide range of symptoms, from mild manifestations, such as itching and perianal discomfort, to the presence of an anal mass, bleeding, and pain. These symptoms often mirror those reported in patients with benign anorectal conditions[11].

HPV is a sufficient cause of anal high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion. Seropositivity for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), herpes simplex virus type 2, treponema pallidum, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus, and a history of gonorrhea or chlamydia are powerful amplifying factors that increase the risk of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion above the risk of HPV alone[12]. The diagnosis of anal cancer involves several steps. A clinical history is taken, a digital anorectal examination is performed, and anoscopy or videoanoscopy may be used, which can be performed during a routine colonoscopy. Additional diagnostic tools include anal cytology with HPV screening and HIV testing and, in some cases, high-resolution anoscopy with biopsy and histological confirmation. It is essential to obtain a sexual history, particularly regarding sexually transmitted infections (STIs), such as HIV and HPV[12]. This includes asking about same-sex sexual activity in men and anal intercourse in women. However, it is worth noting that HPV and anal cancer can occur in individuals of any sex who have not engaged in anal intercourse. Men are primarily asymptomatic carriers and transmitters of HPV. Therefore, vaccinating boys between the ages of 11 and 15 is crucial. This treatment effectively blocks viral transmission and prevents the development of HPV-related cancer[13].

Smoking and immunosuppressant use are significant risk factors for anal lesions. A proctological examination for suspected anal lesions involves a thorough inspection of the anal margin, as well as careful circumferential palpation to assess for the presence of nodules or masses. In addition, inguinal lymph node palpation is performed to detect suspicious lymphadenopathy. Further diagnostic procedures may include anoscopy or videoanoscopy, collection of anal cytology samples for HPV detection and, if necessary, high-resolution anoscopy[2,3,14]. Conventional anoscopy can be performed during the initial consultation without any preparation. The necessary equipment includes a disposable plastic anoscope and a light source specifically designed for the anoscope. The procedure is typically performed without sedation and is generally well tolerated by patients. Conventional anoscopy has several limitations, particularly in terms of obtaining a clear view of lesions within the anal canal. In some cases, examination may be difficult or even impossible because of pain or the presence of feces. Videoanoscopy, on the other hand, is performed during colonoscopy, with the patient under sedation and the colon properly prepared. This allows for the capture of highly magnified, high-definition images using the colonoscope’s advanced chromoscopy and magnification capabilities. The images are then recorded and stored, with a detailed description of the proctological examination included in the colonoscopy report[1,6].

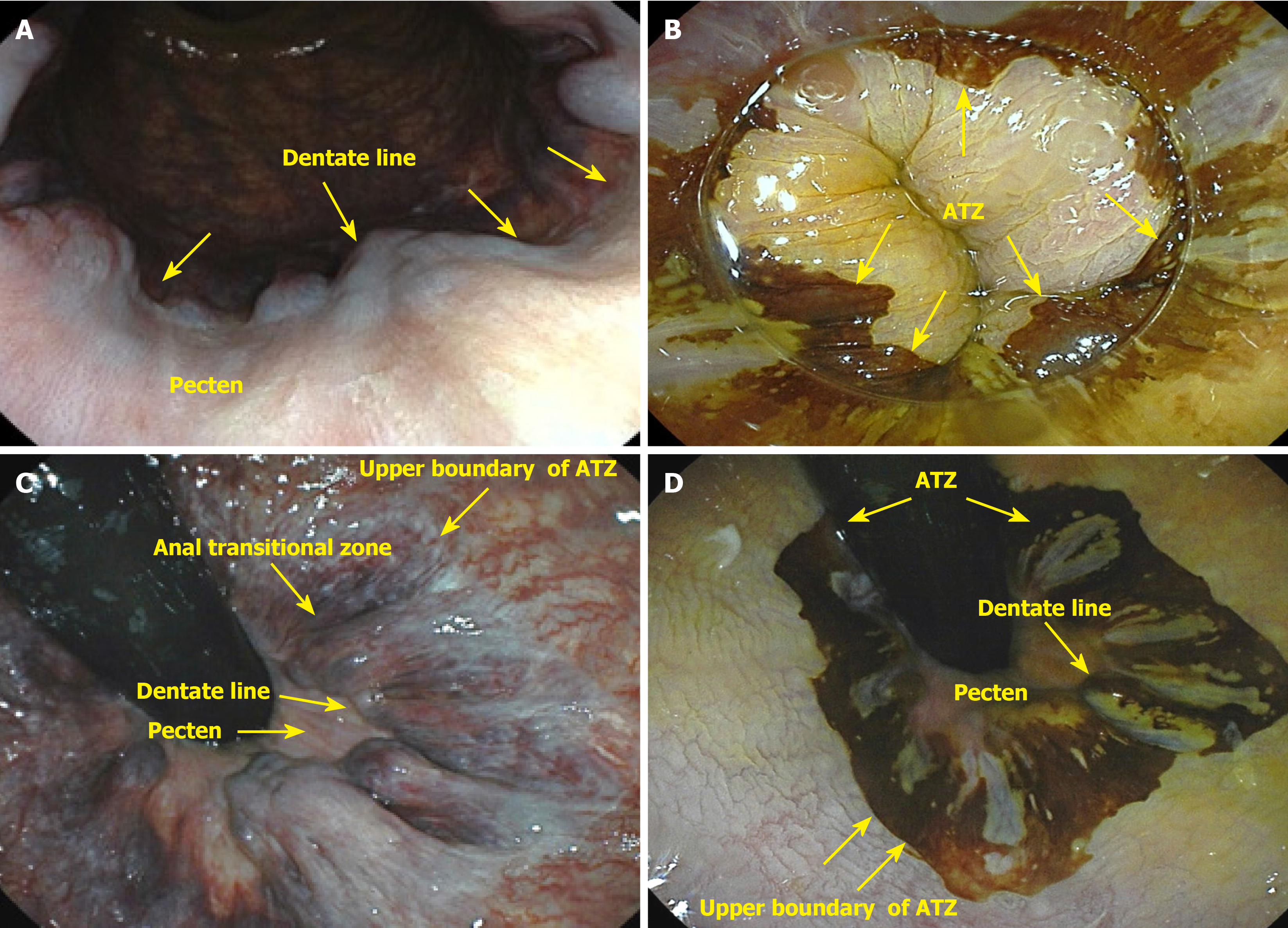

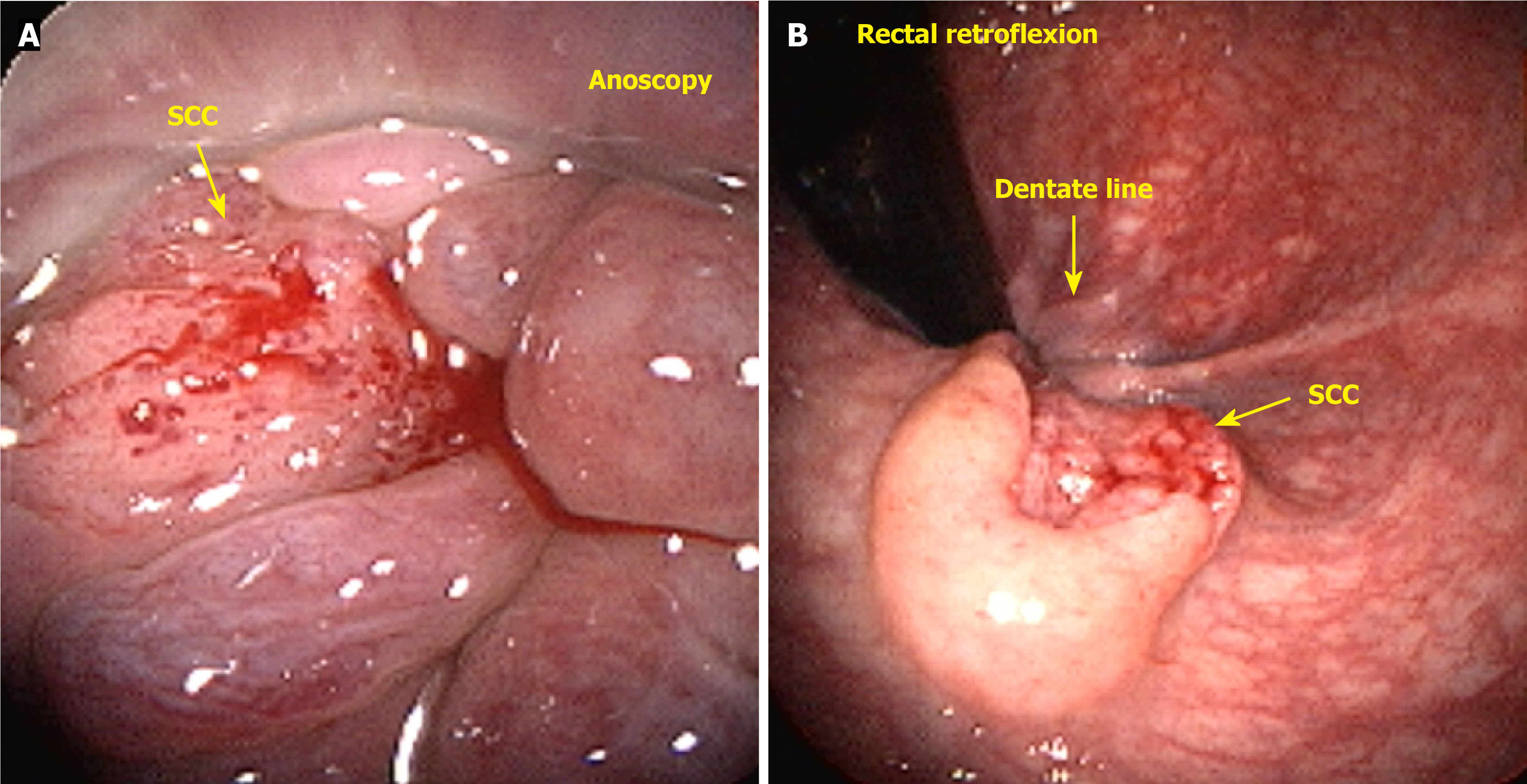

Anal cancer involves malignant growth in the anal canal and surrounding perianal region, including the anal margin. The anal canal spans the anorectal junction, approximately 1 cm above the pectinate line, to the anal verge, also known as Hilton’s white line, marking the boundary between the mucocutaneous and cutaneous zones. The anal margin extends 5 cm radially from the anal verge. The surgical definition of the anal canal is approximately 2-4 cm in length, bounded above by the end of the rectal mucosa and below by the perianal skin. The mucocutaneous junction between these two boundaries comprises the proximal transition zone and distal squamous epithelium (Figure 1). It is important to distinguish tumors arising within the anal canal from those originating in the perianal skin because of their differing biological behaviors and distinct treatment approaches[15]. Tumors located distal to the pectinate line are typically squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) (keratinizing), also known as epidermoid or spinocellular carcinomas[16] (Figure 2).

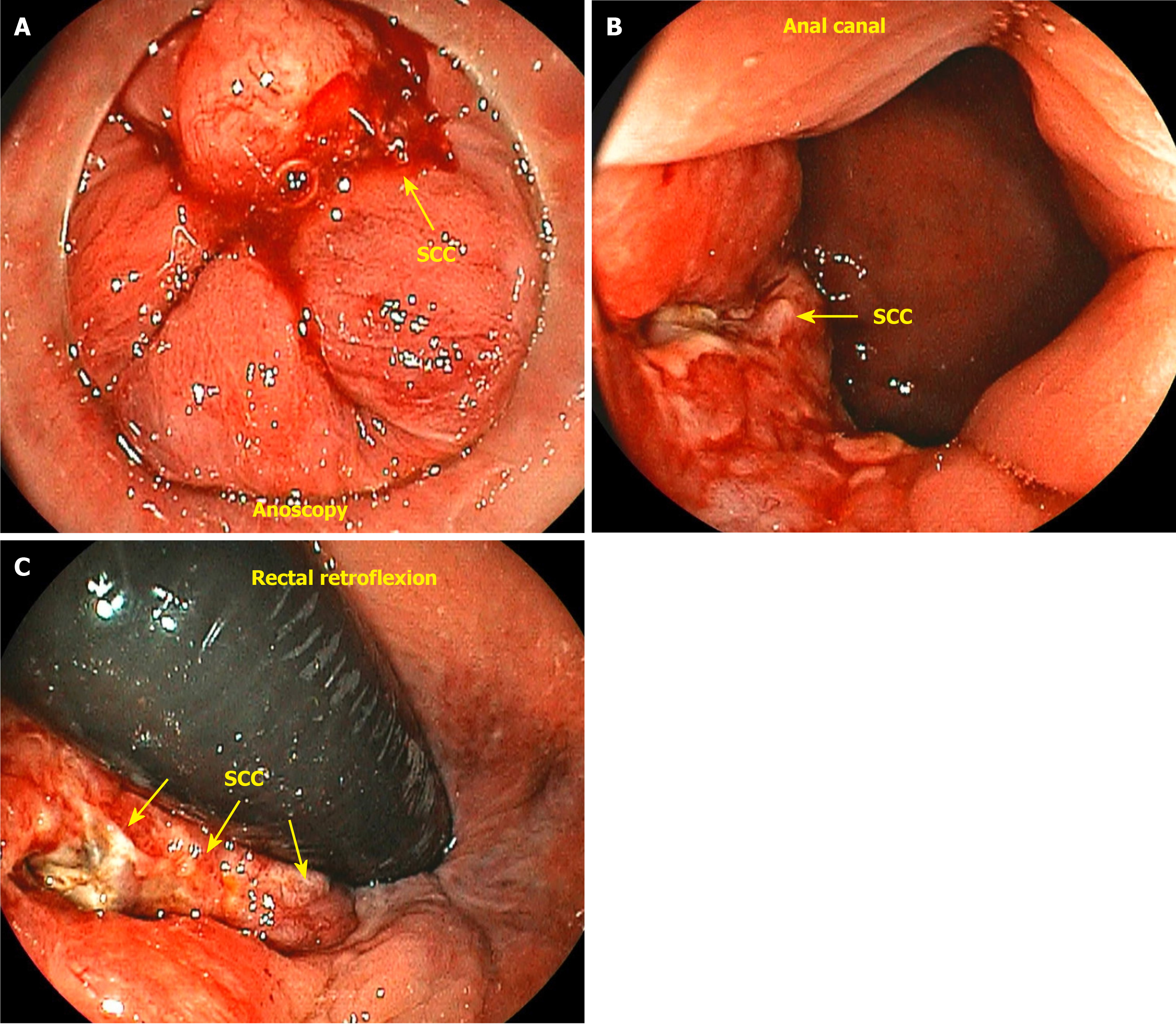

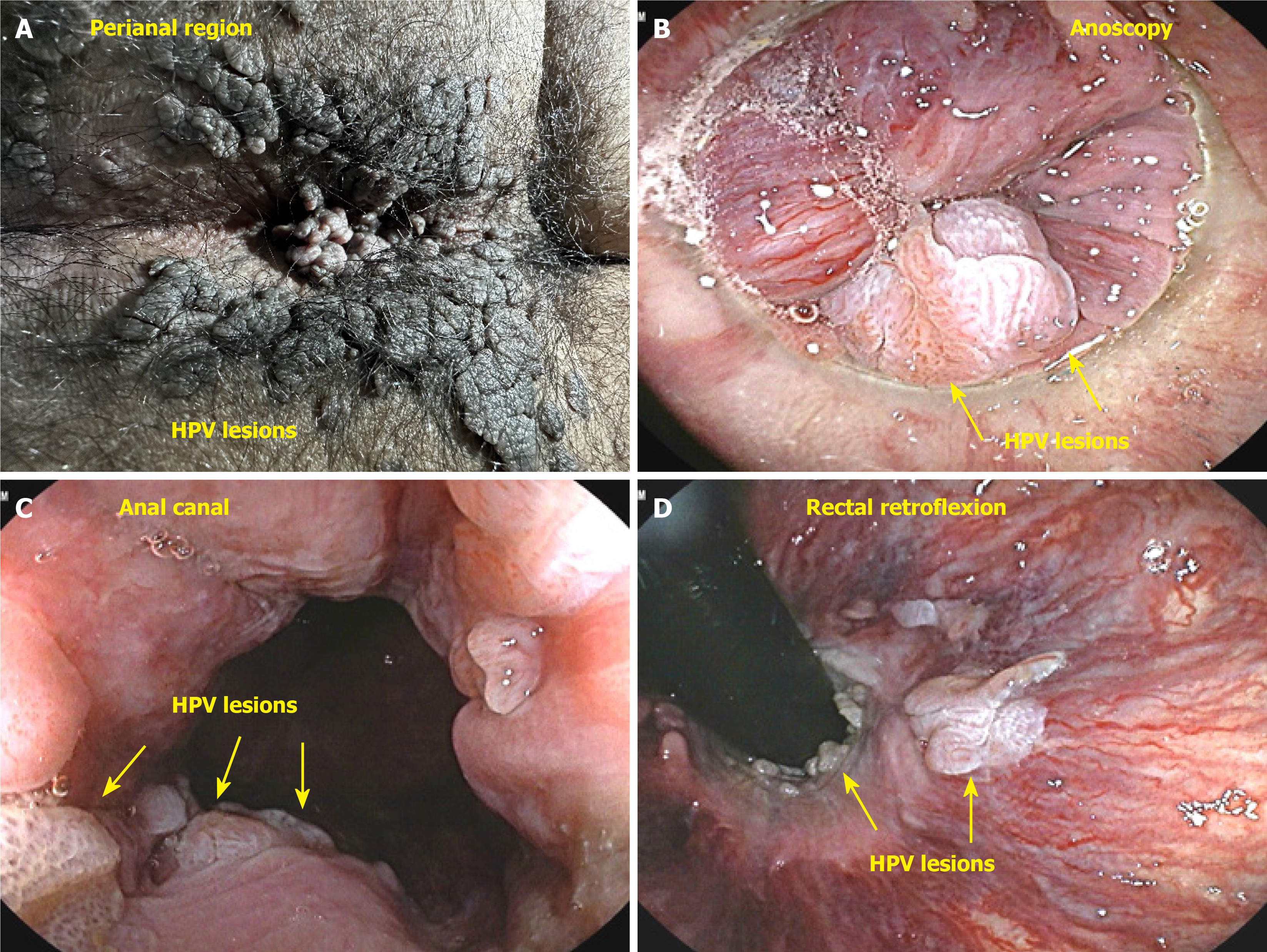

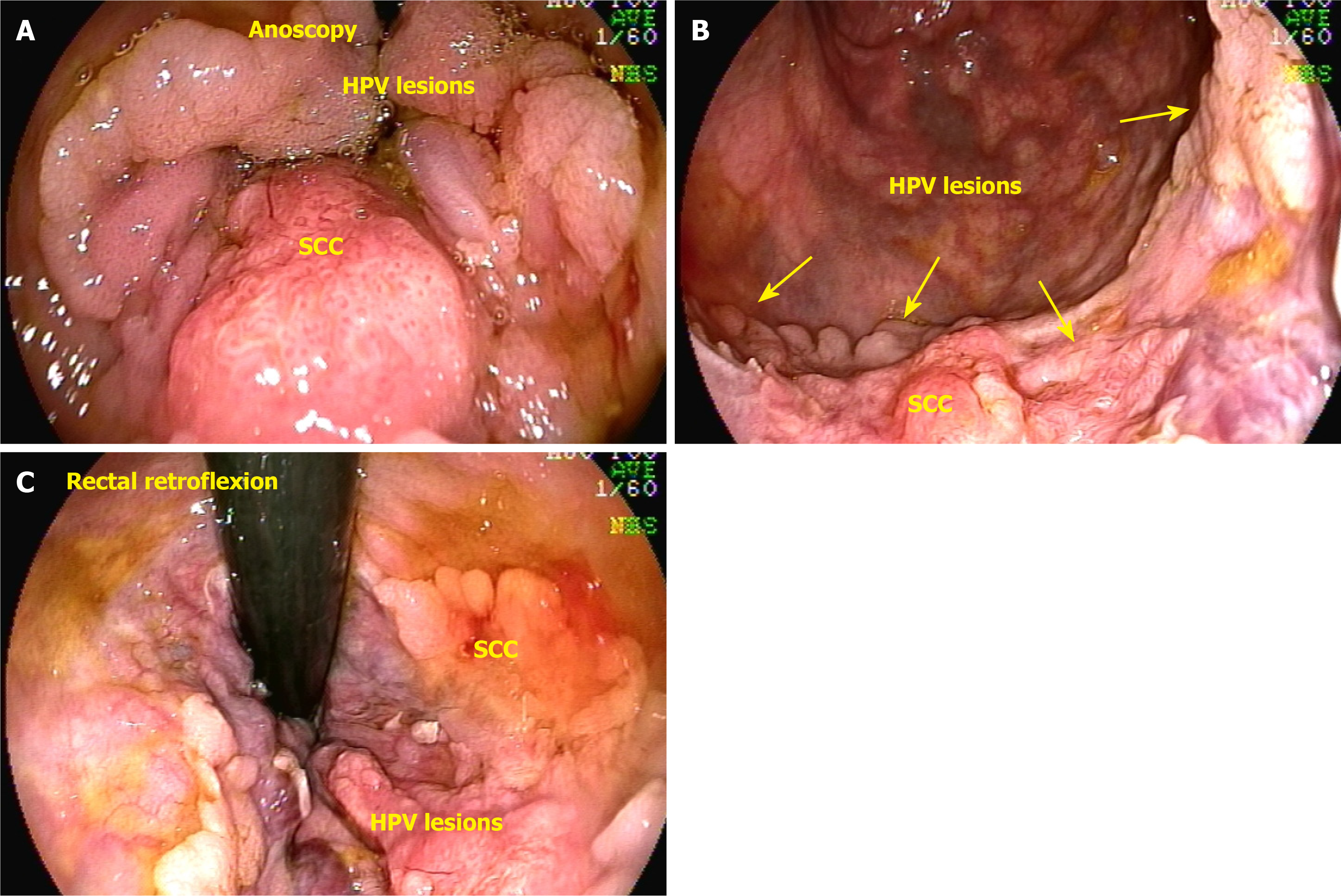

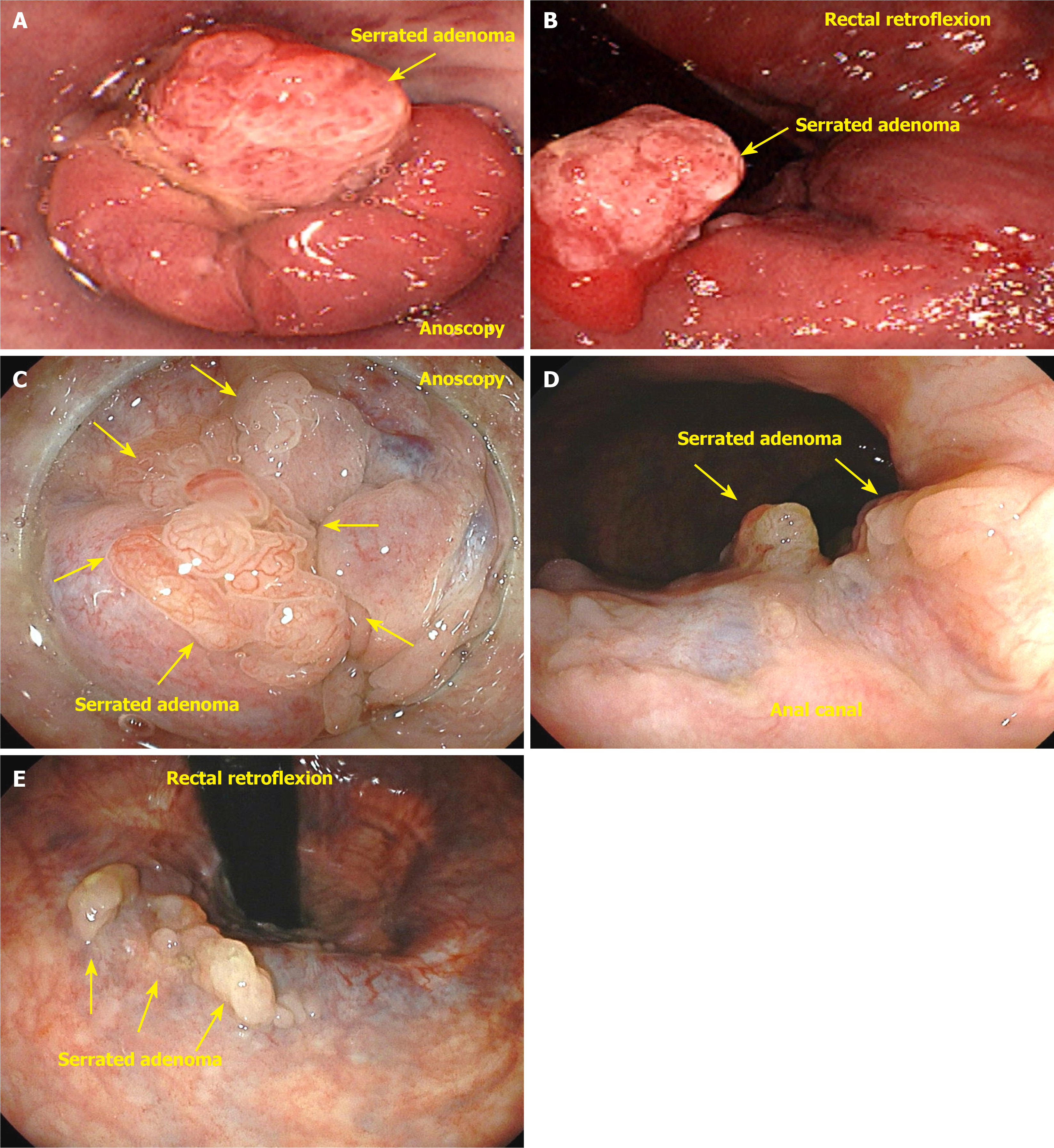

Tumors located just proximal to the pectinate line are typically nonkeratinizing SCCs, also known as basaloid or cloacogenic carcinomas (Figure 3). Approximately 90% of anal SCCs are caused by infection with high-risk HPV[17]. Adenocarcinomas originate from the columnar epithelium found in the proximal part of the anal canal. SCC is the most prevalent type of malignancy of the anus, accounting for approximately 85% of all malignant lesions in this area[18]. The prognosis of carcinoma of the anal margin is generally better than that of tumors of the anal canal. This category of neoplasms includes SCCs, also known as epidermoid carcinoma, Bowen’s disease, Paget’s disease[19], basal cell carcinoma, and giant condylomata acuminata of Bushke-Löwenstein, a rare form of SCCs (Figure 4). Any suspicious lesion located around the anus should be biopsied. The confirmation of malignant neoplasia typically requires treatment with wide local excision. These lesions have a low propensity to metastasize[20].

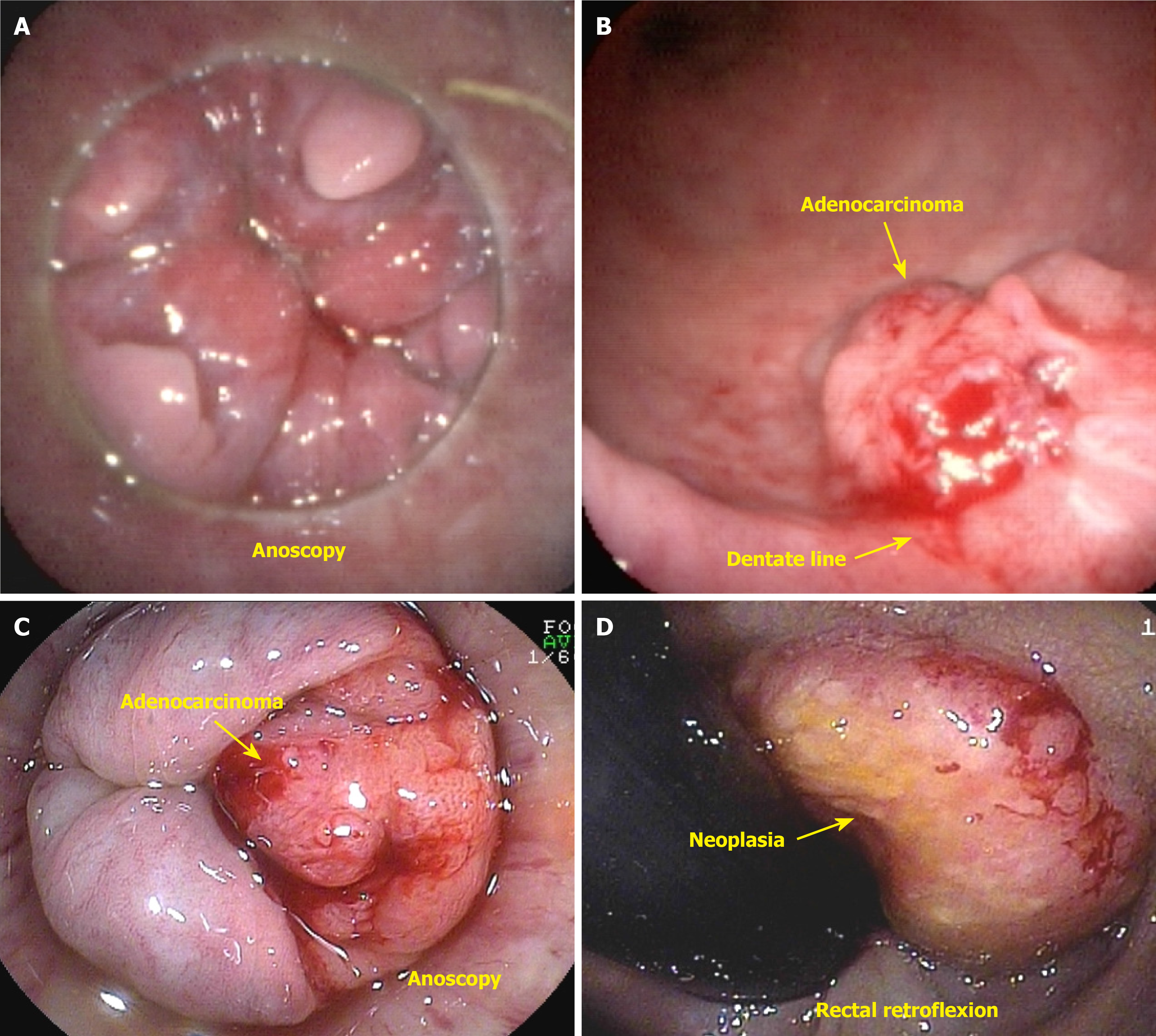

Anal canal cancer is defined as a tumor in which the epicenter is located between the anal verge and 2 cm above the dentate line[21]. Anal canal adenocarcinoma is a rare malignancy characterized by three distinct subtypes. The first subtype involves the upper portion of the anal canal, and the second subtype originates from the anal glands (Figure 5A and B). The third subtype is associated with chronic fistulas[22]. Tumors originating from the upper anal canal are the most common subtype and present the same immunohistochemical characteristics as rectal tumors do. A complicating factor is dual lymphatic drainage to both the femoral and inguinal lymph nodes. Approximately 10% of malignant anal canal lesions are adenocarcinomas; these tumors are characterized by a more aggressive clinical course, higher rates of both local and distant recurrence, and lower survival rates than SCC[23]. The recommended treatment approach involves a combination of neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy, followed by abdominoperineal resection of the rectum and anus and, subsequently, adjuvant chemotherapy[22-24]. Primary adenocarcinoma of the anus can arise from malignant transformation of a chronic anal fistula or from the columnar epithelium lining the anal canal, specifically originating from the anal glands and ducts[16,22]. Anal adenocarcinoma can be classified into two main subtypes: Colorectal and transitional. The colorectal type originates from the distal rectal mucosa and is not associated with HPV (Figure 5C and D). In contrast, the transitional type arises from the mucosa of the anal transition zone or the anal glands, and its development may be influenced by HPV or may occur independently[20,21].

A thorough examination of the lesion is necessary because the lesion could be a tumor originating from the lower rectum that has invaded the anal canal. The anal canal is histologically divided into three distinct zones; each composed of different types of epithelial cells. The colorectal zone is lined by rectal mucosa, which exhibits a specific immunophenotype characterized by the absence of cytokeratin 7 (CK7), the presence of CK20, and the presence of caudal-type homeobox 2. The transition zone is covered by a layer of epithelial cells consisting of basal, parabasal, and epithelial cells. Basal and parabasal cells express squamous markers, such as CK5/CK6 and tumor protein p63, whereas epithelial cells are positive for CK7 and CK19 but negative for CK20 and caudal-type homeobox 2. The squamous zone is lined with squamous epithelium that reacts positively to p40, p63, and CK5/CK6. The anal glands and anal ducts display the same histological characteristics as the transitional epithelium, with identical immunophenotypes[20,25]. Adenocarcinoma of the anal glands or ducts is an extremely rare entity. It is distinct from other forms of anal cancer in that it is not associated with dysplasia of the mucosal surface and does not grow into the lumen of the anal canal. Instead, it manifests as invasion of the sphincter muscles and perianal fat. Adenocarcinomas arising from chronic fistulas are typically the result of long-term inflammatory processes spanning 10 years to 20 years or more and are also associated with Crohn’s disease. Although surveillance programs exist for ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer, there is a lack of specific programs addressing anal cancer in patients with Crohn’s disease[26].

Until recently, robust evidence was lacking to support the screening and treatment of high-grade anal intraepithelial lesions as a preventive measure for anal canal cancer[7]. In 2022, the results from the ANCHOR trial, a prospective multicenter randomized study, were published[27]. The study evaluated 4446 people with HIV who were monitored using high-resolution cytology and anoscopy exams. When high-grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) lesions (AIN 2 p16+ or AIN 3) were identified, participants were randomly assigned to two groups: One in which these lesions were treated and another in which these lesions were monitored every six months. The rate of progression to anal cancer was 53% lower in the treated group than in the control group (P = 0.03). Carriers of HPV, both men and women, account for 80%-85% of all cases of SCC of the anus (SCCA). The primary types responsible for SCCA are HPV16 and HPV18. HPV16 is highly carcinogenic, occurring in 86% of HIV-negative SCCA patients and in 67% of HIV-positive patients. The second most common type is HPV18, which is found in 4% of HIV-negative patients and 15% of HIV-positive patients (Figure 6)[27].

Men who have sex with men (MSM) are 35 times more likely to develop anal cancer than the general population. Moreover, HIV-positive individuals aged > 35 years are 28 times more likely to develop anal cancer[28]. The highest risk group includes MSM and HIV-positive carriers, with 50% of these individuals having high-grade AIN and 10% having anal canal cancer. Women with high-grade neoplasia or lesions in the cervix, vulva, or vagina should be referred to a proctologist for anal evaluation. Other groups with an increased risk of SCCA include transplant recipients receiving immunosuppression therapy; individuals with autoimmune diseases receiving immunosuppression therapy; those with anal Crohn’s disease; carriers of STIs, such as condylomatosis, gonorrhea, genital herpes, syphilis, and chlamydia; and smokers. Smoking increases the risk of SCCA, with the risk being 1.9-fold greater among those who smoke 20 packs per year and 5.2-fold greater among those who smoke 50 packs per year[28,29]. In a 2021 meta-analysis, the incidence of anal cancer was assessed, and the results suggested that standardization is needed in the approach to risk groups (Table 1), especially in the prevention and investigation of anal cancer, which is still in the initial phase in public health[28].

| Risk groups | IRs |

| HIV-positive MSM > 60 years | 107.5 |

| HIV-positive MSM < 30 years | 16.8 |

| HIV-positive MSM | 85 |

| Non-MSM male PLHIV | 32 |

| Female PLHIV | 22 |

| HIV-negative MSM | 19 |

| Solid organ transplant recipients | 13 |

| SOTRs in males > 10 years after transplant | 24.5 |

| SOTRs in females > 10 years after transplant | 49.6 |

| Vulvar cancer | 48 |

| Vaginal cancer | 10 |

| Cervical cancer | 9 |

| Systemic lupus erythematous | 10 |

| Ulcerative colitis | 6 |

| Crohn’s disease | 3 |

This was a retrospective study of outpatients referred for routine colonoscopy. All examinations, including complete anal examination, inspection, digital rectal examination, and videoanoscopy with the recording of images and reports, were saved in a database in a specific program developed for the clinic. The examinations were individually viewed by the work group, and the findings were subjected to statistical analysis.

All patients included in the study completed an admission form with personal data, the reason for requesting the examination, a history of previous injuries or surgeries, and current complaints, including anal symptoms such as pain, changes in bowel habits, frequency of bowel movements, bleeding, hemorrhoidal prolapse, incontinence, and perianal pruritus. All patients included in the study underwent colon preparation. The standard colon preparation protocol consisted of a liquid diet without fiber two days before the examination, 10 mg of bisacodyl the night before the examination, and 750 mL of 10% mannitol four hours before the examination. The criteria for colon preparation were based on the Aronchick scale[30]. Although there are other classifications for colon preparation, such as the Boston classification, which is currently more widely accepted because it specifies the quality of the preparation in each region of the colon, the Aronchick scale was adopted because of its simplicity for application to the rectum, to assess whether the preparation is adequate for anal examination. The aspects evaluated included the demographic distribution of the population, namely, the sex and age of the participants and the presence of various conditions of the anal canal, with special attention to cases of neoplasia and lesions suspected of neoplasia in the anal canal and perianal region. The identified cases of neoplasms were confirmed by histology. Among the cases of anal adenocarcinoma, only those with lesions that met the criteria for surgical anal canal cancer, defined as a tumor in which the epicenter was located between the anal verge and 2 cm above the dentate line, were included.

The reports and images of the exams were recorded and saved in a database called the OCRAM®, SP system. This system was developed using the Java programming language and was used to capture photos of videoanoscopy exams and compose reports from October 2006 to September 2024. The exam reports were structured in extensible markup language (XML) format, following an XML-Schema in accordance with World Wide Web Consortium standards, resulting in a well-formed, valid, and standardized structure of videoanoscopy reports in XML, allowing the mining of terms related to diseases to be performed reliably through the declarative search language structured query language in conjunction with an XML document object model parser.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the outcomes of a systematic anal examination performed during routine colonoscopy for the detection of anal neoplasms. The secondary objective was to emphasize the importance of a thorough examination of the anal area and to demonstrate the potential to identify multiple diagnoses.

Initially, all the variables were analyzed descriptively. For qualitative variables, absolute and relative frequencies were calculated. Statistical data with respect to age, sex, and diagnosis are presented in the tables and are expressed as the means and maximum and minimum values, and categorical variables are expressed as numbers and percentages. Videoanoscopy findings are illustrated in graphs according to sex and age groups. Given the descriptive nature of the study, all variables were analyzed through absolute and percentage frequencies (qualitative variables) and by centrality and dispersion measurements such as the average, SD, minimum, median, and maximum (quantitative variables), generally and stratified by sex and age. No formal hypothesis was tested; thus, no hypothesis test was applied. The calculations were performed with SPSS version 17.0 software. The statistical methods used in this study were reviewed by Estela Cristina Carneseca (PROESTAT)[31].

The project was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of Sorocaba, Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo under decision number 6.753.770 and registered in Plataforma Brasil, CAAE 78588224.5.0000.5373.

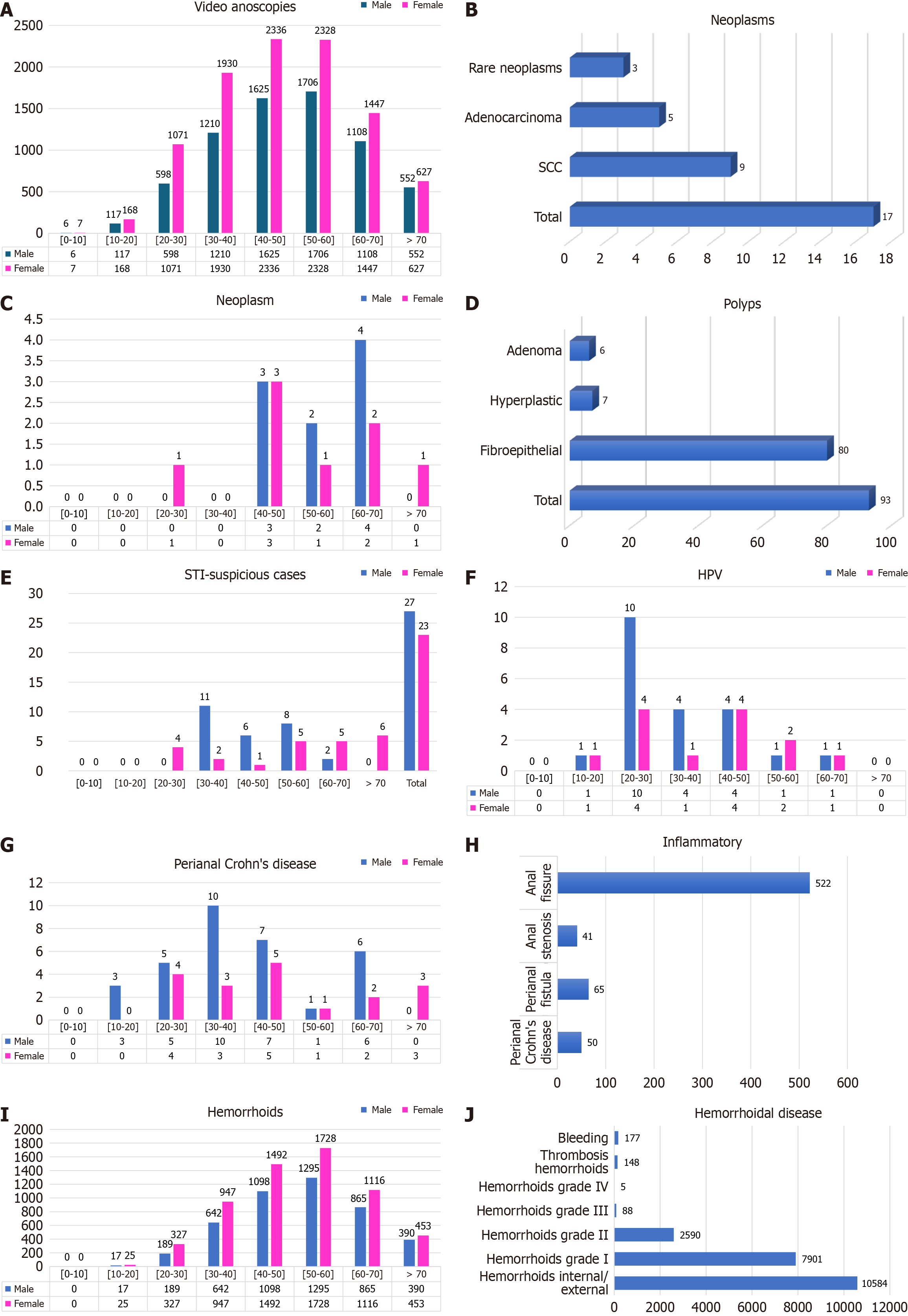

In total, 22676 examinations (colonoscopies with anal examination and video anoscopies) were evaluated in 16836 patients (Table 2), comprising 6922 males (41.11%) and 9914 females (58.89%) (Figure 7A). The mean age was 49 years. On the basis of these findings, 4629 video anoscopies were normal (27.49%), and 12207 (72.51%) had some alterations. We found 17 cases of neoplasms (0.10%), of which 9 cases were SCC (0.05%), 5 cases were adenocarcinoma (0.03%), and 3 cases were rare neoplasias (0.02%) (Figure 7B). Among the 9 patients with SCC (52%), 5 were women, and 4 were men. Among the 5 patients with adenocarcinoma (29%), 2 were women, and 3 were men. There were 3 cases (19%) of rare neoplasia: Gastrointestinal stromal tumor, cavernous hemangioma, and angioleiomyoma (Figure 7C). Polyps were found in the anal canals of 93 patients, of which 80 were fibroepithelial (86%), 7 were hyperplastic polyps (7%), 6 were adenomas (6%), 4 were serrated adenomas, 1 was a tubular adenoma, and 1 was a tubulovillous adenoma with high-grade dysplasia (Figure 7D).

| Variable | Video anoscopies (n = 16836) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Male (n = 6922) | Female (n = 9914) | Total patients | |||||||||||||||||

| Age group | 0-10 | 10-20 | 20-30 | 30-40 | 40-50 | 50-60 | 60-70 | > 70 | Total | 0-10 | 10-20 | 20-30 | 30-40 | 40-50 | 50-60 | 60-70 | > 70 | Total | |

| Age - mean (SD) | 49.61 (14.55) | 48.11 (14.5) | 48.73 (14.54) | ||||||||||||||||

| Age - median (minimum-maximum) | 50 (4-93) | 48 (5-94) | 49 (4-94) | ||||||||||||||||

| Anal examination | 6 (0.09) | 117 (1.69) | 598 (8.64) | 1210 (17.48) | 1625 (23.48) | 1706 (24.65) | 1108 (16.01) | 552 (7.97) | 6922 (41.11) | 7 (0.07) | 168 (1.69) | 1071 (10.8) | 1930 (19.47) | 2336 (23.56) | 2328 (23.48) | 1447 (14.6) | 627 (6.32) | 9914 (58.89) | 16836 (100) |

| Normal | 6 (100) | 77 (65.81) | 300 (50.17) | 392 (32.4) | 340 (20.92) | 260 (15.24) | 145 (13.09) | 121 (21.92) | 1641 (23.71) | 5 (71.43) | 121 (72.02) | 603 (56.3) | 781 (40.47) | 661 (28.3) | 434 (18.64) | 247 (17.07) | 136 (21.69) | 2988 (30.14) | 4629 (27.49) |

| Neoplasms | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.18) | 2 (0.12) | 4 (0.36) | 0 (0) | 9 (0.13) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.09) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.13) | 1 (0.04) | 2 (0.14) | 1 (0.16) | 8 (0.08) | 17 (0.1) |

| SCC | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.06) | 1 (0.06) | 2 (0.18) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.06) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.09) | 1 (0.04) | 2 (0.14) | 0 (0) | 5 (0.05) | 9 (0.05) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.06) | 1 (0.06) | 1 (0.09) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.04) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.04) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.16) | 2 (0.02) | 5 (0.03) |

| Rare neoplasms | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.06) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.09) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.03) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.09) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.01) | 3 (0.02) |

| Polyps | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.5) | 9 (0.74) | 10 (0.62) | 10 (0.59) | 14 (1.26) | 4 (0.72) | 50 (0.72) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.37) | 7 (0.36) | 14 (0.6) | 9 (0.39) | 8 (0.55) | 1 (0.16) | 43 (0.43) | 93 (0.55) |

| Fibroepithelial | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.5) | 6 (0.5) | 10 (0.62) | 9 (0.53) | 11 (0.99) | 3 (0.54) | 42 (0.61) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.37) | 7 (0.36) | 12 (0.51) | 6 (0.26) | 8 (0.55) | 1 (0.16) | 38 (0.38) | 80 (0.48) |

| Hyperplastic | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.17) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.18) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.06) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.04) | 2 (0.09) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.03) | 7 (0.04) |

| Adenoma | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.08) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.06) | 1 (0.09) | 1 (0.18) | 4 (0.06) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.04) | 1 (0.04) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.02) | 6 (0.04) |

| HPV | 0 (0) | 1 (0.85) | 10 (1.67) | 4 (0.33) | 4 (0.25) | 1 (0.06) | 1 (0.09) | 0 (0) | 21 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | 4 (0.37) | 1 (0.05) | 4 (0.17) | 2 (0.09) | 1 (0.07) | 0 (0) | 13 (0.13) | 34 (0.2) |

| Perianal Crohn’s disease | 0 (0) | 3 (2.56) | 5 (0.84) | 10 (0.83) | 7 (0.43) | 1 (0.06) | 6 (0.54) | 0 (0) | 32 (0.46) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.37) | 3 (0.16) | 5 (0.21) | 1 (0.04) | 2 (0.14) | 3 (0.48) | 18 (0.18) | 50 (0.3) |

| Perianal fistula | 0 (0) | 1 (0.85) | 9 (1.51) | 16 (1.32) | 12 (0.74) | 10 (0.59) | 3 (0.27) | 0 (0) | 51 (0.74) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.19) | 3 (0.16) | 5 (0.21) | 3 (0.13) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.16) | 14 (0.14) | 65 (0.39) |

| Thrombosis hemorrhoids | 0 (0) | 6 (5.13) | 10 (1.67) | 23 (1.9) | 21 (1.29) | 16 (0.94) | 3 (0.27) | 2 (0.36) | 81 (1.17) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 10 (0.93) | 22 (1.14) | 17 (0.73) | 12 (0.52) | 5 (0.35) | 1 (0.16) | 67 (0.68) | 148 (0.88) |

| Anal stenosis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.08) | 3 (0.18) | 3 (0.18) | 9 (0.81) | 4 (0.72) | 20 (0.29) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.09) | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.04) | 6 (0.26) | 4 (0.28) | 7 (1.12) | 21 (0.21) | 41 (0.24) |

| Bleeding | 0 (0) | 2 (1.71) | 8 (1.34) | 28 (2.31) | 38 (2.34) | 25 (1.47) | 13 (1.17) | 7 (1.27) | 121 (1.75) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | 6 (0.56) | 11 (0.57) | 10 (0.43) | 16 (0.69) | 9 (0.62) | 3 (0.48) | 56 (0.56) | 177 (1.05) |

| Anal fissure | 0 (0) | 9 (7.69) | 47 (7.86) | 65 (5.37) | 50 (3.08) | 39 (2.29) | 15 (1.35) | 7 (1.27) | 232 (3.35) | 2 (28.57) | 12 (7.14) | 80 (7.47) | 80 (4.15) | 57 (2.44) | 41 (1.76) | 14 (0.97) | 4 (0.64) | 290 (2.93) | 522 (3.1) |

| Hemorrhoids total | 0 (0) | 17 (14.53) | 189 (31.61) | 642 (53.06) | 1098 (67.57) | 1295 (75.91) | 866 (78.16) | 390 (70.65) | 4497 (64.97) | 0 (0) | 25 (14.88) | 327 (30.53) | 947 (49.07) | 1492 (63.87) | 1728 (74.23) | 1116 (77.13) | 453 (72.25) | 6088 (61.41) | 10585 (62.87) |

| Hemorrhoids grade I | 0 (0) | 16 (13.68) | 161 (26.92) | 518 (42.81) | 793 (48.8) | 822 (48.18) | 507 (45.76) | 219 (39.67) | 3036 (43.86) | 0 (0) | 24 (14.29) | 295 (27.54) | 842 (43.63) | 1242 (53.17) | 1324 (56.87) | 828 (57.22) | 311 (49.6) | 4866 (49.08) | 7902 (46.94) |

| Hemorrhoids grade II | 0 (0) | 1 (0.85) | 27 (4.52) | 119 (9.83) | 297 (18.28) | 463 (27.14) | 350 (31.59) | 165 (29.89) | 1422 (20.54) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | 31 (2.89) | 103 (5.34) | 236 (10.1) | 386 (16.58) | 278 (19.21) | 133 (21.21) | 1168 (11.78) | 2590 (15.38) |

| Hemorrhoids grade III | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.17) | 5 (0.41) | 7 (0.43) | 10 (0.59) | 9 (0.81) | 6 (1.09) | 38 (0.55) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.09) | 2 (0.1) | 13 (0.56) | 18 (0.77) | 10 (0.69) | 6 (0.96) | 50 (0.5) | 88 (0.52) |

| Hemorrhoids grade IV | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.06) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.01) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.04) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.48) | 4 (0.04) | 5 (0.03) |

| Others | 0 (0) | 1 (0.85) | 16 (2.68) | 22 (1.82) | 34 (2.09) | 38 (2.23) | 29 (2.62) | 15 (2.72) | 155 (2.24) | 0 (0) | 7 (4.17) | 32 (2.99) | 71 (3.68) | 61 (2.61) | 73 (3.14) | 45 (3.11) | 18 (2.87) | 307 (3.1) | 462 (2.74) |

The “others” category included 461 cases (2.47%) of various inflammatory processes, such as nonspecific ulcerations in the anal canal, inflammatory granulomas, perianal dermatitis, and anoproctitis. We identified 50 cases (0.31%) of proctitis or perianal dermatitis suspicious for STI that were referred for a specialized evaluation (male patients: 54%; female patients: 46%) (Figure 7E). After the tests, two cases of primary syphilis, one case of perianal herpetic dermatitis, one case of gonococcus, and one case of anorectal chlamydia were confirmed. The remaining 45 patients with negative test results were treated for nonspecific perianal dermatitis. We found 34 cases (0.20%) of verrucous lesions with anatomopathological examination showing koilocytosis (condylomatous lesion-HPV), with a predominance of males (21 patients, 61.76%) over females (13 patients, 38.24%) (Figure 7F).

Perianal Crohn’s disease was noted in 50 patients (0.30%), including fissures, fistulas, and ulcerated lesions in the anal canal (Figure 7G and H). Sixty-five cases of perianal fistula (0.35%) were identified by the external orifice and mucus or purulent discharge at the time of videoanoscopy. There was a predominance of males (51 patients, 78.46%) over females (14 patients, 21.54%). Hemorrhoidal disease was found in 10584 patients (62.87%) and was staged according to the hemorrhoid findings as I, II, III, or IV. Hemorrhoidal bleeding at the time of examination was noted in 177 patients (1.05%), and thrombosed hemorrhoids were noted in 148 patients (0.88%) (Figure 7I and J).

The objective of this study was to assess the spectrum of diagnoses, the prevalence of anal disorders in different age groups, and the importance of anal examinations in colonoscopy to assess anal diseases. Suspicious lesions along the dentate line may often be undetected by colonoscopists who do not perform a routine assessment of the anal canal. It is very common for endoscopists to insert the colonoscope into the rectum without identifying anal or very low rectal lesions. These lesions should be identified and removed by a colonoscopist with adequate training. We have observed that many colonoscopy reports do not mention anything about anal examinations, and some reports include a footnote stating that colonoscopy is not an appropriate method for assessing the anal and perianal regions. Over the past 35 years, we have routinely performed anal examinations as part of the colonoscopy report using videoanoscopy. Systematic performance of anal examinations and anoscopy means including in all colonoscopy examinations the evaluation of the anal canal and perianal region, using inspection, digital anorectal examination, evaluation with the frontal view of the colonoscope, and videoanoscopy.

We begin the proctological evaluation with a brief clinical history of the patient, which is initiated by the nurse who fills out a form with the reason for the examination, complaints, pain, bleeding characteristics, history, previous surgeries, and previous examinations. We then have a brief conversation before sedation regarding the patient’s clinical history. The most important information is attached to the colonoscopy report. After sedation, we begin inspecting the perianal region and anal margin, which is approximately 5 cm in circumference, looking for fissures, fistula orifices, scar retractions, deformities, skin lesions, and dermatitis. Next, a circumferential touch is performed to observe whether there is pain, hypertonia, hypotonia, or lesions. Next, the colon is inserted, the liquid content is aspirated, the anal canal is viewed frontally, and rectal retroflexion (RR) is performed in selected cases. Then, videoanoscopy and image recording were performed.

Digital anorectal examination is essential before any colonoscopy. It assesses whether there is stenosis, lesions, tumors, or sphincter tone. It is a mandatory part of every colonoscopy. The addition of a more complete anal evaluation to all colonoscopies is the subject of this paper. However, the main goal of this work is to add a simple and quick exam to be performed at the time of colonoscopy, with the patient sedated and with the colon well prepared to make a good evaluation of the anal region and not fail to diagnose lesions. The goal is to ensure that small lesions are not overlooked during routine colonoscopy. RR is only performed in selected cases. For patients who presented with anal bleeding, for better visualization of internal hemorrhoids and stigmata of recent bleeding, we used the RR. In the case of suspicion of neoplasia close to the dentate line, we performed RR as a complement to the evaluation. Complications of RR are rare, but cases of perforation, laceration, and bleeding have been described. It has formal contraindications, mainly due to friability of the rectal wall, as in actinic proctopathy, in inflammatory bowel disease, in the recent postoperative period with colorectal anastomoses, and in elderly patients with incontinence who do not retain the insufflated air.

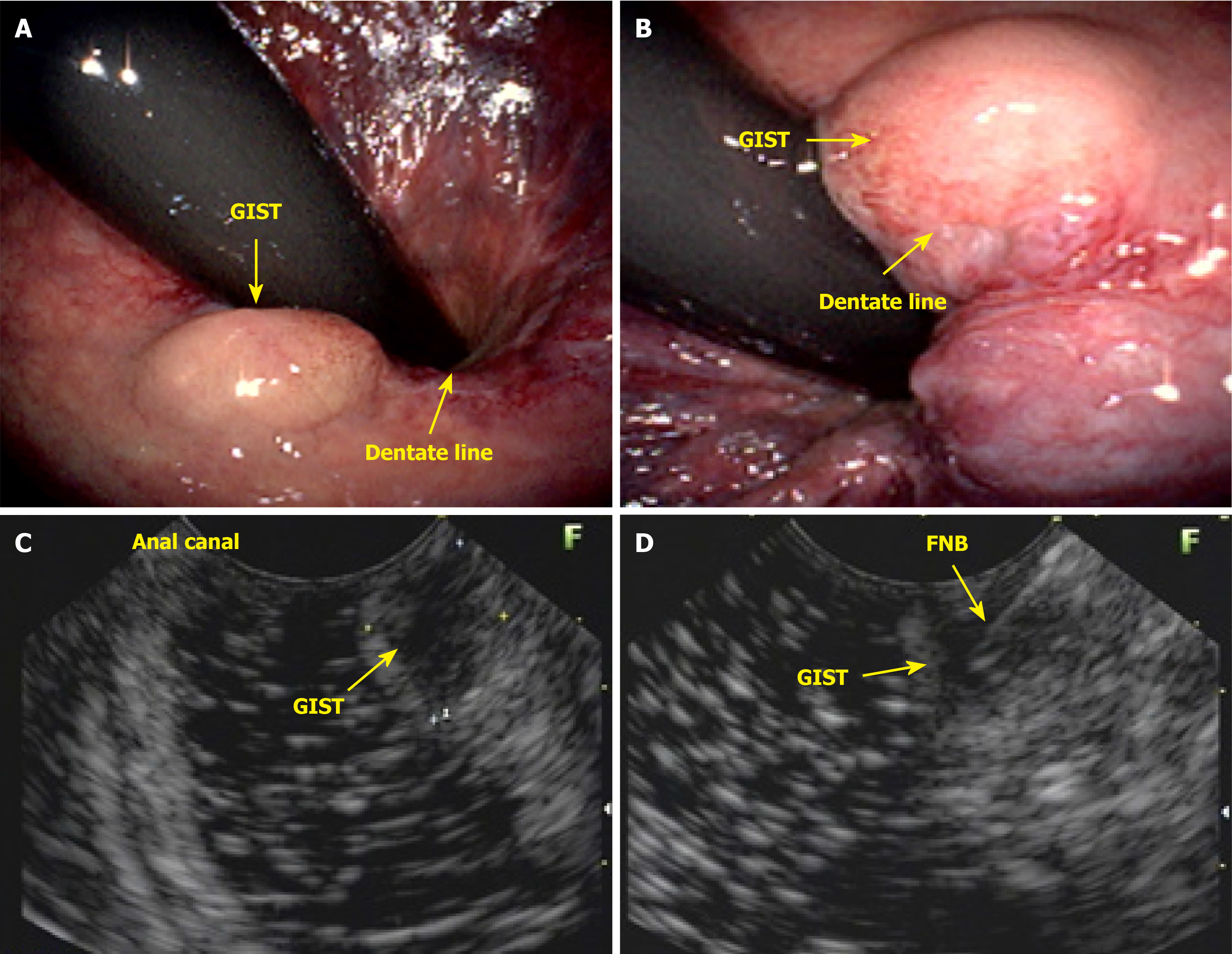

As the number of requests for colonoscopy from clinicians, gynecologists, and physicians outside the field of coloproctology continues to rise, the responsibility of diagnosing, treating, and guiding patients with anal lesions often falls to the endoscopist. In countries with limited healthcare systems, where patients face challenges accessing specialists, an endoscopist with knowledge of anal pathologies can diagnose these lesions and, in many cases, provide the necessary treatment. Furthermore, the endoscopist should remove premalignant anal canal lesions (Figure 8). Lesions in the anal canal should be biopsied or removed during colonoscopy. This patient presented with a subepithelial nodule in the anal canal, which was evaluated and biopsied via endoscopic ultrasound. Histological analysis revealed a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (Figure 9).

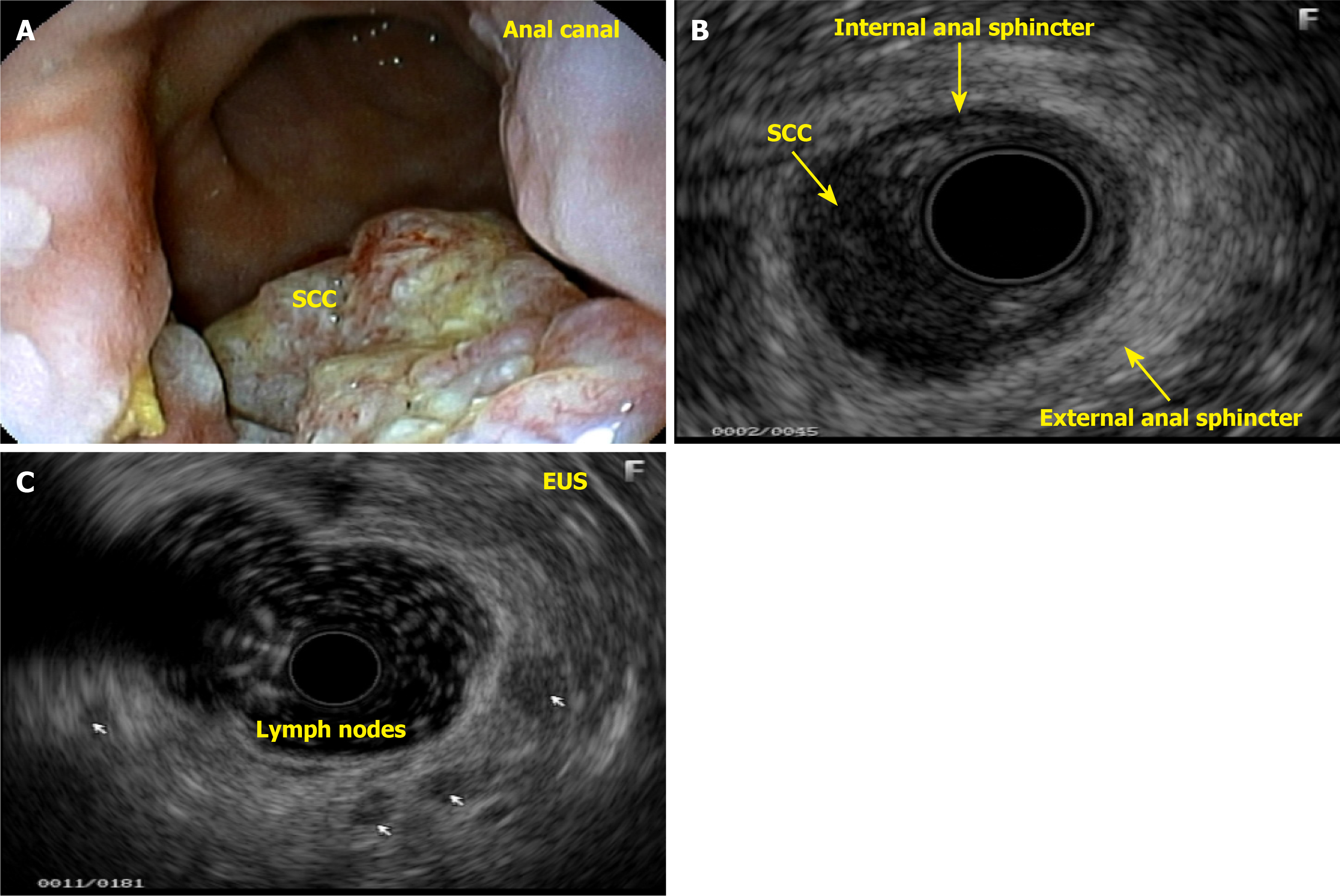

Diagnostic endoanal ultrasound (EAUS) offers several clinically significant benefits in the evaluation and management of anal neoplasms, particularly anal SCC. EAUS provides high-resolution, real-time imaging of the anal canal, allowing for precise assessment of tumor depth, involvement of the internal and external anal sphincters, and perirectal tissue invasion. This detailed local staging is critical for treatment planning, especially in distinguishing early-stage tumors that may be amenable to less aggressive therapy from those requiring more extensive intervention. EAUS is cost-effective, well-tolerated, and can be performed in patients with contraindications to magnetic resonance imaging, such as those with certain implants or severe claustrophobia. However, EAUS is operator-dependent and may be limited in patients with anal stenosis or extensive disease, and its ability to assess lymph node involvement is inferior to that of magnetic resonance imaging. Despite these limitations, EAUS remains a valuable tool for initial staging, treatment planning, and posttreatment surveillance in anal neoplasms, particularly when high-resolution assessment of the anal sphincter complex and local tumor extent is needed.

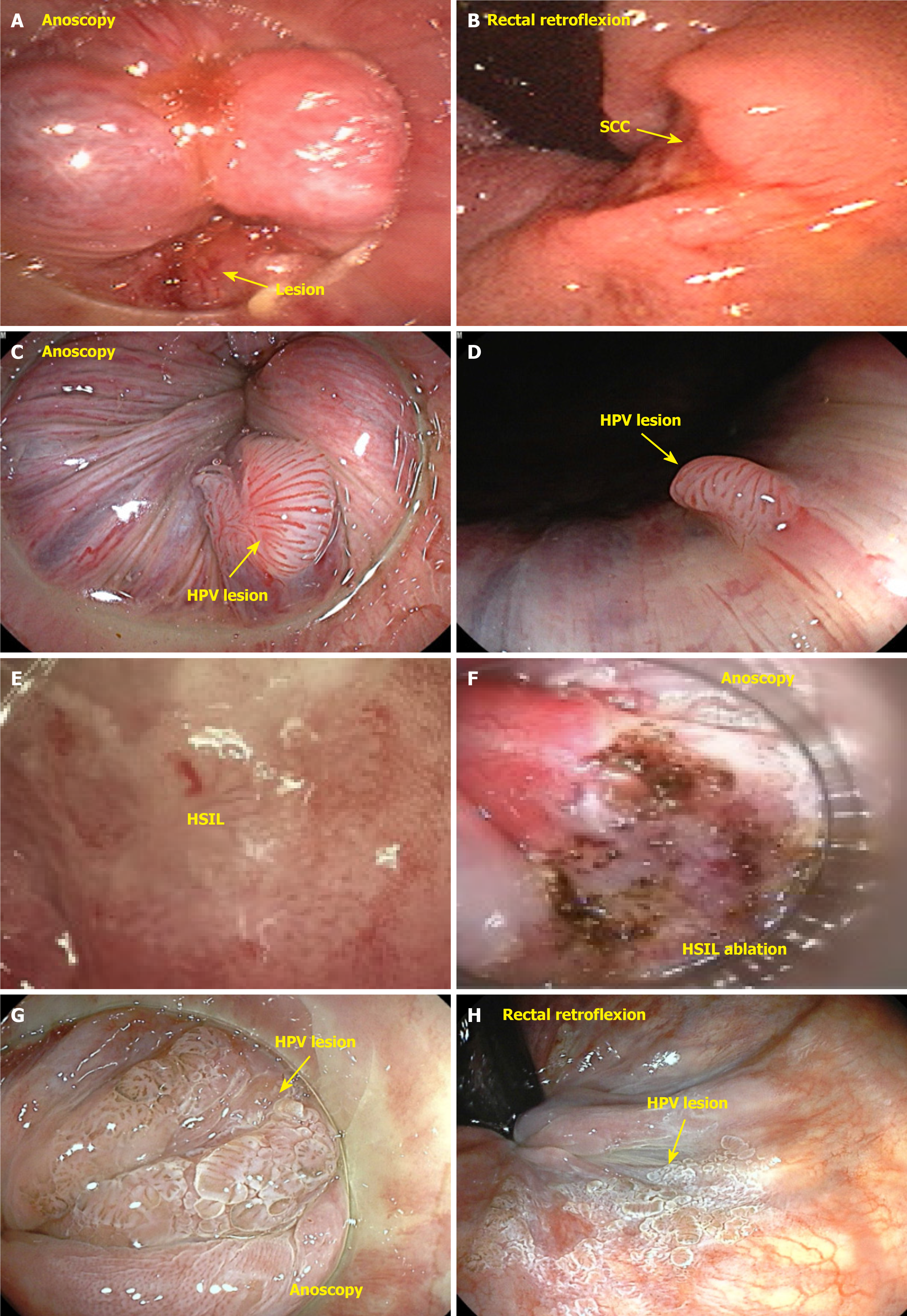

This patient complained of bleeding during bowel movements, and a colonoscopy revealed a small, ulcerated lesion in the anal canal. A histological study revealed SCC (Figure 10A and B). Patients with HPV-related lesions can have their evaluation extended through the appropriate use of dyes and targeted biopsies, and lesions can be properly resected immediately without the need for a new appointment, which can take too long, thereby eliminating the chance of early cure. Many lesions are subtle, small, and challenging to identify. A thorough and close inspection is necessary to detect small nodules and distinct changes in the mucosa of the anal canal (Figure 10C and D). The colonoscopist can also collect material via brush cytology and request laboratory tests when there is a suspicion of an STI.

Until the publication of the ANCHOR study, no solid evidence was available to support the screening and treatment of high-grade anal intraepithelial lesions as a preventive method for anal and anal canal cancer[7,28]. There is significant evidence supporting the development of clinical guidelines using anal cytology and HPV testing for anal cancer screening[17,32]. The ANCHOR study, published in 2022, revealed a 57% reduction in the risk of anal canal cancer with the ablation of high-grade AIN[27]. Ablation of high-grade AIN can be performed by electrofulguration (Figure 10E and F), argon, lasers, infrared coagulation, radiofrequency, or topical agents, such as imiquimod cream, trichloroacetic acid, and 5-fluorouracil cream. However, it has a high recurrence rate of 68% in patients with HPV16 and HPV18 at 36 months[27,33].

Margin anal and anal canal cancers are rare and should not be screened in the general population[34]. However, their incidence increases significantly in certain populations, such as people with HIV, MSM, women with a history of gynecological cancer or high-grade lesions, and patients with immunosuppression, which justifies screening in these groups. Furthermore, many patients omit information regarding sexual activity, STIs and previous treatments, which justifies performing an anal examination in all routine colonoscopies. The identification and treatment of high-grade anal intraepithelial lesions in individuals with HIV can effectively prevent anal cancer. HPV infection does not confer complete immunity, and the vaccine is indicated even for patients infected with HPV. The tetravalent vaccine (6, 11, 16, and 18) is provided by the public health system for girls aged 9 years to 15 years and boys aged 11 years to 15 years.

Although the use of colposcopy equipment has become standard for evaluating lesions in the anal canal, only a few centers have specialized in this technique. This procedure can be performed with equal effectiveness via magnification colonoscopy and the same dyes used in colposcopy, such as acetic acid (Figure 10G and H) and Lugol’s solution, or by utilizing the capabilities of colonoscopes equipped with magnification and chromoscopy, along with light filters such as narrow band imaging and Fuji intelligent chromo endoscopy. It is essential to extend the evaluation to the perianal region. Oette et al[35] demonstrated that chromoendoscopy performed via videoanoscopy is both safe and effective for diagnosing AIN. Inkster, at the Cleveland clinic, described 25 cases of anal dysplasia (15 Low-grade and 10 high-grade) in routine colonoscopy for colorectal cancer screening between 2011 and 2018[36,37]. The initial treatment for the anal canal is chemoradiotherapy[38]. Local excision and slice or piecemeal resection of carcinomas are generally contraindicated for invasive lesions because they have an unacceptable rate of positive margins and a recurrence rate of 78%. Well-differentiated lesions measuring up to 2 cm with invasion into the submucosa can be resected by local excision, with a margin of more than 1 cm, and are associated with chemoradiotherapy. Radical resection, abdominoperineal amputation of the rectum and anus, and inguinal lymphadenectomy are used for advanced, residual, or recurrent lesions. Immunotherapy is a promising treatment for advanced-stage metastases (Figure 11). On the other hand, at the anal margin, initial lesions can be treated with local resection with a margin > 1 mm if there is no sphincter involvement.

The systematic performance of anal examination and anoscopy in all routine colonoscopies has allowed the identification of numerous anal diseases, including rare and incidental cases of anal cancer and several lesions suspected of being anal canal or anal margin cancer. On the basis of the findings of this study, we propose that anal examinations and anoscopy should be performed during routine colonoscopies, especially in high-risk groups, and that, additional tests should be performed in suspected cases.

Marco Aurélio M C Regis (OCRAM SYSTEMS) created all the tables, graphics, and figures; Estela Cristina Carneseca (PROESTAT) conducted the statistical analysis.

| 1. | Gomes A, Minata MK, Jukemura J, de Moura EGH. Video anoscopy: results of routine anal examination during colonoscopies. Endosc Int Open. 2019;7:E1549-E1562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Albuquerque A, Etienney I. Identification and Reporting of Anal Pathology during Routine Colonoscopies. J Coloproctol. 2023;43:152-158. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zinicola R, Viani L, Rossini M, Cozzani F. Concerning "Updates on the Version 9 American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging System for Anal Cancer": Is the Anal Physical Examination Underestimated? Ann Surg Oncol. 2025;32:1132-1133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kelly SM, Sanowski RA, Foutch PG, Bellapravalu S, Haynes WC. A prospective comparison of anoscopy and fiberendoscopy in detecting anal lesions. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1986;8:658-660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lazas DJ, Moses FM, Wong RK. Videoendoscopic anoscopy: a new technique for examining the anal canal. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:351-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gomes A. Videoanuscopia: resultados do exame anal de rotina durante as colonoscopias. Doctoral dissertations, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo. 2020. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72:7-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4235] [Cited by in RCA: 11955] [Article Influence: 2988.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 8. | Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:12-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2279] [Cited by in RCA: 6020] [Article Influence: 3010.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 9. | Mignozzi S, Santucci C, Malvezzi M, Levi F, La Vecchia C, Negri E. Global trends in anal cancer incidence and mortality. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2024;33:77-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Leeds IL, Fang SH. Anal cancer and intraepithelial neoplasia screening: A review. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;8:41-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Gondal TA, Chaudhary N, Bajwa H, Rauf A, Le D, Ahmed S. Anal Cancer: The Past, Present and Future. Curr Oncol. 2023;30:3232-3250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | McCloskey JC, Kast WM, Flexman JP, McCallum D, French MA, Phillips M. Syndemic synergy of HPV and other sexually transmitted pathogens in the development of high-grade anal squamous intraepithelial lesions. Papillomavirus Res. 2017;4:90-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cai X, Xu L. Human Papillomavirus-Related Cancer Vaccine Strategies. Vaccines (Basel). 2024;12:1291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Albuquerque A. High-resolution anoscopy: Unchartered territory for gastroenterologists? World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7:1083-1087. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Grulich AE, Poynten IM, Machalek DA, Jin F, Templeton DJ, Hillman RJ. The epidemiology of anal cancer. Sex Health. 2012;9:504-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hoff PM, Coudry R, Moniz CM. Pathology of Anal Cancer. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2017;26:57-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Clarke MA, Deshmukh AA, Suk R, Roberts J, Gilson R, Jay N, Stier EA, Wentzensen N. A systematic review and meta-analysis of cytology and HPV-related biomarkers for anal cancer screening among different risk groups. Int J Cancer. 2022;151:1889-1901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Magalhães MN, Barbosa LER. Anal canal squamous carcinoma. J Coloproctol. 2017;37:72-79. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ishii K, Takahashi H, Tsuji H, Ishihara T, Iwami Y, Juavijitjan W, Yokota M, Takaichi S, Paku M, Iwamoto K, Ohashi T, Nakahara Y, Asaoka T, Matsuda C, Nishikawa K, Omori T. Clinical and Pathological Analysis of Perianal Paget's Disease: A Case Report and Review of 89 Cases. Cancer Diagn Progn. 2025;5:49-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Liao X. A Review and Update on Epithelial Tumors of the Anal Canal. J Clin Transl Pathol. 2022;2:149-158. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Taliadoros V, Rafique H, Rasheed S, Tekkis P, Kontovounisios C. Management and Outcomes in Anal Canal Adenocarcinomas-A Systematic Review. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:3738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ferrer Márquez M, Velasco Albendea FJ, Belda Lozano R, Berenguel Ibáñez Mdel M, Reina Duarte Á. [Adenocarcinoma of the anal canal. Narrative review]. Cir Esp. 2013;91:281-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chang GJ, Gonzalez RJ, Skibber JM, Eng C, Das P, Rodriguez-Bigas MA. A twenty-year experience with adenocarcinoma of the anal canal. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1375-1380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Shao X, Zhang Q, Huo Y, Lu C. Rational treatment options for T1/2N0M0 squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal: a population-based study combined with external validation. Oncologist. 2024;29:e1003-e1011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hester R, Advani S, Rashid A, Holliday E, Messick C, Das P, You YN, Taniguchi C, Koay EJ, Bednarski B, Rodriguez-Bigas M, Skibber J, Wolff R, Chang GJ, Minsky BD, Foo WC, Rothschild N, Morris VK, Eng C. CEA as a blood-based biomarker in anal cancer. Oncotarget. 2021;12:1037-1045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kayano H, Okada KI, Yamamoto S, Koyanagi K. Establishment of a surveillance program for anal cancer in Crohn's disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30:4844-4849. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 27. | Palefsky JM, Lee JY, Jay N, Goldstone SE, Darragh TM, Dunlevy HA, Rosa-Cunha I, Arons A, Pugliese JC, Vena D, Sparano JA, Wilkin TJ, Bucher G, Stier EA, Tirado Gomez M, Flowers L, Barroso LF, Mitsuyasu RT, Lensing SY, Logan J, Aboulafia DM, Schouten JT, de la Ossa J, Levine R, Korman JD, Hagensee M, Atkinson TM, Einstein MH, Cracchiolo BM, Wiley D, Ellsworth GB, Brickman C, Berry-Lawhorn JM; ANCHOR Investigators Group. Treatment of Anal High-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions to Prevent Anal Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:2273-2282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 334] [Article Influence: 83.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Clifford GM, Georges D, Shiels MS, Engels EA, Albuquerque A, Poynten IM, de Pokomandy A, Easson AM, Stier EA. A meta-analysis of anal cancer incidence by risk group: Toward a unified anal cancer risk scale. Int J Cancer. 2021;148:38-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 324] [Cited by in RCA: 351] [Article Influence: 70.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Gomes A, Sampaio Netto JB, Ayres RDO, Rodrigues JMDS, Borghesi RA. Sexually Transmitted Infections Lesions Found during Colonoscopies. J Coloproctol. 2023;43:75-81. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 30. | Kastenberg D, Bertiger G, Brogadir S. Bowel preparation quality scales for colonoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:2833-2843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (10)] |

| 31. | Rosner B. Fundamentals of Biostatistics. 7th ed. United States: Cengage Learning, 2010. |

| 32. | Clarke MA, Wentzensen N. Strategies for screening and early detection of anal cancers: A narrative and systematic review and meta-analysis of cytology, HPV testing, and other biomarkers. Cancer Cytopathol. 2018;126:447-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Stewart DB, Gaertner WB, Glasgow SC, Herzig DO, Feingold D, Steele SR; Prepared on Behalf of the Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for Anal Squamous Cell Cancers (Revised 2018). Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61:755-774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Roy AC, Wattchow D, Astill D, Singh S, Pendlebury S, Gormly K, Segelov E. Uncommon Anal Neoplasms. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2017;26:143-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Oette M, Wieland U, Schünemann M, Haes J, Reuter S, Jensen BE, Sagir A, Pfister H, Häussinger D. Anal chromoendoscopy using gastroenterological video-endoscopes: A new method to perform high resolution anoscopy for diagnosing intraepithelial neoplasia and anal carcinoma in HIV-infected patients. Z Gastroenterol. 2017;55:23-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Inkster MD, Wiland HO, Wu JS. Detection of anal dysplasia is enhanced by narrow band imaging and acetic acid. Colorectal Dis. 2016;18:O17-O21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Inkster MD, Wu JS. Anal dysplasia detection during routine screening colonoscopy. Surg Case Rep Rev. 2018;2:1-5. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Benson AB, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, Cederquist L, Chen YJ, Ciombor KK, Cohen S, Cooper HS, Deming D, Engstrom PF, Grem JL, Grothey A, Hochster HS, Hoffe S, Hunt S, Kamel A, Kirilcuk N, Krishnamurthi S, Messersmith WA, Meyerhardt J, Mulcahy MF, Murphy JD, Nurkin S, Saltz L, Sharma S, Shibata D, Skibber JM, Sofocleous CT, Stoffel EM, Stotsky-Himelfarb E, Willett CG, Wuthrick E, Gregory KM, Freedman-Cass DA. Anal Carcinoma, Version 2.2018, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16:852-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/