Published online Oct 16, 2025. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v17.i10.107984

Revised: June 9, 2025

Accepted: September 19, 2025

Published online: October 16, 2025

Processing time: 197 Days and 10.8 Hours

The optimal management of gallstones and common bile duct stones remains a subject of ongoing debate. The conventional two-stage treatment involves initial endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) to clear the bile duct, followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Alternatively, the single-stage lapa

To evaluate the efficacy, safety, and logistical considerations of these two ap

A literature search was conducted through a PubMed search (2010-2024) using the terms “laparoendoscopic rendezvous”, “endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography”, and “cholecystocholedocholithiasis”. Only English-language studies were included.

In our analysis, LERV significantly reduced the incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis by 67% (2.4% vs 8.8%) and shortened hospital stay by a mean of up to 6 days. Stone clearance rates were comparable between LERV (97%) and the two-stage approach (96%). Although LERV was associated with a longer operative time (139.8 minutes vs 107.7 minutes), it demonstrated lower overall costs, largely due to reduced hospitalization. Rates of postoperative bleeding, cholangitis, and bile leak were low and did not differ significantly between groups.

The single-stage LERV approach is safe, effective, and associated with lower pancreatitis rates, shorter hospital stays, and reduced costs compared to the two-stage strategy. Its implementation, however, requires coordinated surgical-endoscopic expertise, making it most suitable for well-equipped centers and carefully selected patients.

Core Tip: The conventional two-stage approach separates endoscopic and surgical interventions, whereas the single-stage laparoendoscopic rendezvous procedure provides a more streamlined alternative. This study highlights the advantages of laparoendoscopic rendezvous, including shorter hospital stay, a reduced risk of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis, and improved bile duct clearance. Furthermore, we examine its feasibility across various healthcare settings, particularly in low-volume centers, where procedural consolidation could enhance outcomes. Future studies should focus on refining patient selection and evaluating long-term benefits to optimize clinical practice.

- Citation: Lauri A, Cocomello L, Fabiani S, Lauri G, Rando G. Gallstones and common bile duct stones management: Single-stage vs two-stage treatment. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2025; 17(10): 107984

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v17/i10/107984.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v17.i10.107984

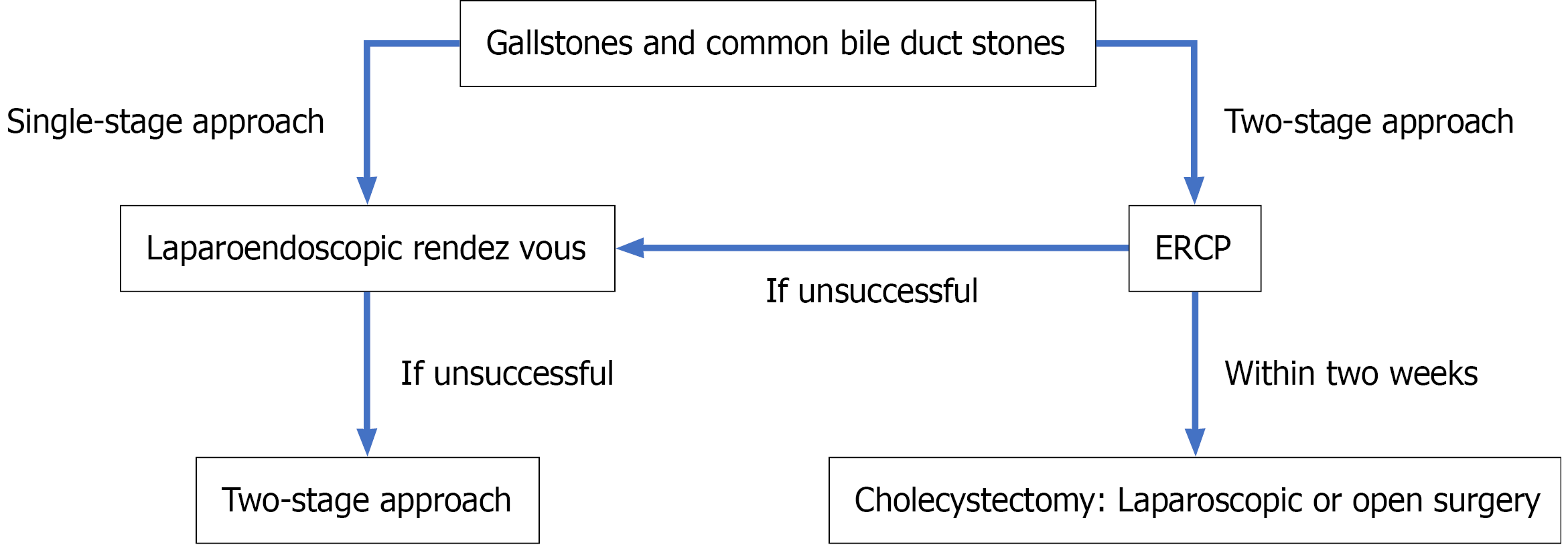

Biliary lithiasis is a prevalent condition worldwide, affecting approximately 20% of the general population[1]. It is responsible for 10%-15% of cases of common bile duct stones (CBDS)[2], which can lead to symptoms and complications in 25% of patients[3], including obstructive jaundice, acute pancreatitis, and cholangitis[4]. European guidelines recommend that patients with CBDS, whether symptomatic or not, undergo stone extraction if they are fit enough to tolerate the procedure[5]. While treatment for gallstones typically involves laparoscopic cholecystectomy (VLC), the management of gallstones associated with CBDS remains a debated issue[6]. The decision-making process for managing CBDS involves two possible strategies: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) followed by VLC, or a single-stage laparoendoscopic rendezvous (LERV) procedure. The choice between these methods is influenced by various factors such as the availability of technical resources, the number and size of stones, the expertise of the endoscopists, and local protocols (Figure 1). This study compares the efficacy, safety, and resource utilization of these two approaches.

ERCP combines endoscopy and fluoroscopy to diagnose and treat conditions affecting the bile and pancreatic ducts. The procedure involves the insertion of a duodenoscope into the second portion of the duodenum, followed by the deep cannulation of the biliary duct and injection of contrast agents for fluoroscopic imaging. This allows for direct visualization of abnormalities such as strictures, stones, or tumors. ERCP is commonly used for treating CBDS, enabling stone removal with specialized instruments, such as balloon and basket catheters. Emerging minimally invasive techniques, including cholangioscopy-assisted intraluminal lithotripsy (electrohydraulic or laser), are increasingly applied in difficult choledocholithiasis cases, particularly in high-resource settings.

LERV is an alternative technique that integrates laparoscopic surgery with endoscopic intervention. It involves VLC to remove the gallbladder while simultaneously addressing CBDS through endoscopic methods. The procedure includes selective common bile duct cannulation facilitated by the laparoscopic placement of a guidewire through the cystic duct into the duodenum.

This study was conducted to explore and compare the outcomes of single-stage LERV and the conventional two-stage approach ERCP followed by VLC in the management of concomitant gallstones and CBDS. A literature search was performed using PubMed, covering studies published from 2010 to 2024. The search terms included “laparoendoscopic rendezvous”, “endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography”, and “cholecystocholedocholithiasis”. Only English-language studies were considered. Study selection was guided by clinical relevance and the authors’ expertise in the field. Both randomized controlled trials and high-quality non-randomized studies were included to ensure a comprehensive overview of clinical outcomes, perioperative complications, and healthcare resource utilization. Key studies identified include Qian et al[7], Tzovaras et al[8], which were used to derive crude complication rates, and Lin et al[9], which was used for comparisons. The final analysis incorporated eight studies, five randomized controlled trials and three non-randomized comparative studies, encompassing a total of 542 patients who underwent LERV and 519 who received the two-stage approach. Data were synthesized using a combination of narrative analysis and pooled estimates, where applicable, to evaluate differences in outcomes such as stone clearance rates, incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis, operative time, hospital stay, and procedural costs (Table 1).

| Ref. | Year | Study type | Number of patients [LERV vs (ERCP + LC)] | Outcome |

| Qian et al[7] | 2020 | Retrospective cohort study | 123 vs 137 | LERV: Lower post-procedure pancreatitis, shorter hospital stays, significantly longer operative time |

| Tzovaras et al[8] | 2012 | Randomized clinical trial | 50 vs 49 | LERV: Shorter hospital stays and lower incidence of post-procedure hyperamylasemia |

| Lin et al[9] | 2020 | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 542 vs 519 | LERV: Less pancreatitis, lower overall morbidity, and shorter hospital stay but longer operation time. |

| Tan et al[11] | 2018 | Meta-analysis | 313 vs 317 (intra-operative sphincterotomy vs pre-operative sphincterotomy) | Intraoperative sphincterotomy: Less incidence of post-operative pancreatitis, overall morbidity, less hospital stays |

| ElGeidie et al[12] | 2010 | Randomized prospective study | 98 vs 100 (intra-operative sphincterotomy vs pre-operative sphincterotomy) | When there are enough experience and adequate facilities, the single-stage treatment would be preferable. |

| La Greca et al[13] | 2009 | Review | 795 (LERV) | LERV: Lower risk of post-procedure pancreatitis and lower risk of residual stones |

| Lauri et al[18] | 2024 | Retrospective cohort study | 228 vs 478 | LERV: Quicker, shorter hospital stay, highly effective, more comfortable for the patient, safe, cheaper |

The analysis revealed no significant difference between LERV and the two-stage approach in terms of successful common bile duct stone clearance. Qian et al[7] reported stone clearance rates of 97% for LERV and 96% for the two-stage approach, a finding supported by the meta-analysis, which showed no statistically significant difference [odds ratio (OR) = 2.20, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.86-5.64, P = 0.10], although heterogeneity across the studies was observed (P = 0.01). It is important to note that intraoperative cholangiography may occasionally miss intrahepatic duct stones, and both ERCP and LERV may misinterpret air bubbles as retained stones. Thus, neither approach guarantees 100% clearance.

Regarding postoperative complications, LERV demonstrated a lower incidence of pancreatitis. Tzovaras et al[8] reported fewer cases of post-ERCP hyperamylasemia in the LERV group. Similarly, Qian et al[7] found that postoperative pancreatitis occurred in 2.4% of patients undergoing LERV, compared to 8.8% in the two-stage approach group. Meta-analysis confirmed a significantly lower incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis with LERV (OR = 0.26, 95%CI: 0.12-0.54, P = 0.0003). The rates of postoperative bleeding were 0% for LERV and 0.7% for the two-stage approach, with no significant difference between the groups (meta-analytic OR = 0.67, 95%CI: 0.26-1.61, P = 0.37). Postoperative cholangitis occurred in 0% of LERV patients and 3.6% of those undergoing the two-stage approach, with no significant difference (meta-analytic OR = 0.66, 95%CI: 0.18-2.37, P = 0.53). Similarly, the rate of postoperative bile leakage was comparable between the two groups, at 0.8% for LERV and 0.7% for the two-stage approach (meta-analytic OR = 0.87, 95%CI: 0.28-2.70, P = 0.81)[9].

A systematic review published by Vettoretto et al[10] reached a more conservative conclusion regarding the benefits of LERV compared to the two-stage approach. However, several subsequent studies, including those by Qian et al[7] and Lin et al[9], have added further evidence supporting the safety, feasibility, and potential advantages of the single-stage strategy. In terms of resource utilization, LERV has generally been associated with reduced hospital stays and healthcare costs. Qian et al[7] reported relatively long hospitalizations, with an average stay of 12 days for LERV patients compared to 18 days for those treated with the two-stage approach (mean difference = -3.52, 95%CI: -4.69 to -2.35, P < 0.00001). In contrast, other studies have observed significantly shorter durations. For example, Tan et al[11] reported mean stays of 3.52 days for LERV and 6.1 days for the two-stage group. These discrepancies likely reflect differences in institutional protocols, perioperative management strategies, and healthcare system organization.

Despite its logistical advantages, LERV was associated with longer operative times, averaging 139.8 minutes compared to 107.7 minutes for the two-stage approach, an expected finding given the combined nature of the procedure. Nevertheless, LERV was associated with lower overall costs, likely due to reduced hospital stays and fewer procedural steps[7,9].

The standard approach for treating CBDS involves preoperative ERCP followed by VLC[11]. However, this method has several drawbacks, such as the need for multiple hospital admissions (two or three if residual CBDS are present), double or triple anesthesia, and prolonged hospital stay. Moreover, while in many institutions VLC is performed during the same hospitalization following ERCP, often within 24-48 hours, this timing may vary depending on the patient’s clinical status or institutional logistics. Delays are particularly common in the presence of post-ERCP complications such as pancreatitis or cholangitis, which may postpone VLC for several days after the initial ERCP. In contrast, the LERV procedure has been proposed as an alternative, as it combines both procedures into a single stage, with coordination between both surgical and endoscopic teams[12,13].

Furthermore, ERCP can fail to cannulate the ampulla of Vater in 4%-18% of cases, leading to one of its most common and feared complications: Post-ERCP pancreatitis, which occurs due to inadvertent pancreatic duct cannulation and contrast injection[14]. These complications are less frequent in high-volume centers (> 200 ERCPs per year), where procedural success rates are higher and hospital stay is shorter compared to low-volume centers (< 200 ERCPs per year)[15,16]. In fact, in low-volume centers, ERCP success rates have been reported to drop below 80%, potentially limiting the feasibility of ERCP[15]. In this context, the LERV approach offers significant advantages, particularly in reducing hospital stay and minimizing the risk of pancreatitis.

The use of a guidewire passed through the cystic duct to facilitate common bile duct cannulation during LERV enhances procedural success and safety. This technique is particularly beneficial for patients with CBDS ≤ 10 mm and normal anatomy, where stone extraction success rates should exceed 90%[17]. However, LERV’s longer operative time may present challenges in terms of operating room utilization and prolonged anesthesia exposure. In our experience, the procedure adds an average of only 20-35 minutes compared to standard VLC, and only one anesthesia is required, compared to two or three in the two-stage approach, especially if residual cystic duct stones remain after VLC[18].

The need for close collaboration between surgical and endoscopic teams limits the applicability of this technique, as it requires both institutional expertise and adequate resources. The requirement for real-time collaboration between surgical and endoscopic teams may be a barrier in many institutions, highlighting the need for interdisciplinary simulation-based training. Another relevant aspect is the technical complexity and learning curve associated with transcystic bile duct exploration, further emphasizing the need for dedicated training programs and structured institutional support. Moreover, LERV may not be feasible in patients with severe acute cholangitis, acute cholecystitis, or significant comorbidities that contraindicate surgery, as this approach requires clinical stability and the ability to perform VLC under general anesthesia. Stone size in the common bile duct also represents a limiting factor. Stones larger than 15 mm are more difficult to extract[17]. In cases where stone extraction fails, endoscopic placement of a plastic biliary stent may serve as a rescue strategy, providing effective biliary drainage[17]. Additionally, the stent may exert a mechanical erosion effect on the stone, potentially facilitating its extraction at a subsequent endoscopic session[17]. An additional key factor to consider is patient preference. Patients favor a single-sedation procedure over undergoing two separate sessions with two different types of anesthesia. Patient selection is therefore critical, and LERV is particularly suited for those who would benefit from a single-session approach, while the standard two-stage procedure may be more appropriate in settings with less integrated teams or for patients with specific risk factors for prolonged surgery.

One of LERV’s distinct advantages is its ability to eliminate residual CBDS after VLC, as intraoperative fluoroscopy and guidewire placement through the cystic duct ensure complete stone clearance. Moreover, the single-stage nature of LERV helps to reduce costs by shortening hospital stay. From a patient-centered perspective, LERV may provide psychological benefits by reducing the stress and inconvenience associated with multiple hospital admissions, an aspect often underestimated in clinical decision-making. Nevertheless, several limitations affect the current evidence. Considerable heterogeneity among studies, including differences in surgical expertise, stone characteristics, and patient comorbidities, compromises the generalizability of the findings. Moreover, long-term outcomes such as biliary stricture formation or recurrent CBDS remain poorly documented. Additional high-quality randomized controlled trials are needed to validate the long-term effectiveness of LERV and to better define optimal patient selection criteria.

The single-stage LERV procedure for managing gallstones and CBDS is preferred by patients and demonstrates fast, safe, and effective outcomes. It offers several advantages, including complete stone clearance, lower pancreatitis incidence, improved patient comfort, shorter hospital stays, and reduced costs compared to the standard two-stage approach. However, the need for coordinated surgical and endoscopic teams suggests that LERV is best suited for centers with appropriate expertise and for patients who would benefit from a single-session procedure. Future research should focus on conducting large-scale trials to further refine patient selection criteria.

| 1. | Everhart JE, Khare M, Hill M, Maurer KR. Prevalence and ethnic differences in gallbladder disease in the United States. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:632-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 549] [Cited by in RCA: 548] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tazuma S. Gallstone disease: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and classification of biliary stones (common bile duct and intrahepatic). Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:1075-1083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 262] [Cited by in RCA: 317] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Möller M, Gustafsson U, Rasmussen F, Persson G, Thorell A. Natural course vs interventions to clear common bile duct stones: data from the Swedish Registry for Gallstone Surgery and Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (GallRiks). JAMA Surg. 2014;149:1008-1013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Halldestam I, Enell EL, Kullman E, Borch K. Development of symptoms and complications in individuals with asymptomatic gallstones. Br J Surg. 2004;91:734-738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 221] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Williams E, Beckingham I, El Sayed G, Gurusamy K, Sturgess R, Webster G, Young T. Updated guideline on the management of common bile duct stones (CBDS). Gut. 2017;66:765-782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 31.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Manes G, Paspatis G, Aabakken L, Anderloni A, Arvanitakis M, Ah-Soune P, Barthet M, Domagk D, Dumonceau JM, Gigot JF, Hritz I, Karamanolis G, Laghi A, Mariani A, Paraskeva K, Pohl J, Ponchon T, Swahn F, Ter Steege RWF, Tringali A, Vezakis A, Williams EJ, van Hooft JE. Endoscopic management of common bile duct stones: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline. Endoscopy. 2019;51:472-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 463] [Cited by in RCA: 434] [Article Influence: 62.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Qian Y, Xie J, Jiang P, Yin Y, Sun Q. Laparoendoscopic rendezvous versus ERCP followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy for the management of cholecysto-choledocholithiasis: a retrospectively cohort study. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:2483-2489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Tzovaras G, Baloyiannis I, Zachari E, Symeonidis D, Zacharoulis D, Kapsoritakis A, Paroutoglou G, Potamianos S. Laparoendoscopic rendezvous versus preoperative ERCP and laparoscopic cholecystectomy for the management of cholecysto-choledocholithiasis: interim analysis of a controlled randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2012;255:435-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lin Y, Su Y, Yan J, Li X. Laparoendoscopic rendezvous versus ERCP followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the management of cholecystocholedocholithiasis: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:4214-4224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Vettoretto N, Foglia E, Ferrario L, Arezzo A, Cirocchi R, Cocorullo G, Currò G, Marchi D, Portale G, Gerardi C, Nocco U, Tringali M, Anania G, Piccoli M, Silecchia G, Morino M, Valeri A, Lettieri E. Why laparoscopists may opt for three-dimensional view: a summary of the full HTA report on 3D versus 2D laparoscopy by S.I.C.E. (Società Italiana di Chirurgia Endoscopica e Nuove Tecnologie). Surg Endosc. 2018;32:2986-2993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tan C, Ocampo O, Ong R, Tan KS. Comparison of one stage laparoscopic cholecystectomy combined with intra-operative endoscopic sphincterotomy versus two-stage pre-operative endoscopic sphincterotomy followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy for the management of pre-operatively diagnosed patients with common bile duct stones: a meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:770-778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | ElGeidie AA, ElEbidy GK, Naeem YM. Preoperative versus intraoperative endoscopic sphincterotomy for management of common bile duct stones. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1230-1237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | La Greca G, Barbagallo F, Sofia M, Latteri S, Russello D. Simultaneous laparoendoscopic rendezvous for the treatment of cholecystocholedocholithiasis. Surg Endosc. 2009;24:769-780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Freeman ML, DiSario JA, Nelson DB, Fennerty MB, Lee JG, Bjorkman DJ, Overby CS, Aas J, Ryan ME, Bochna GS, Shaw MJ, Snady HW, Erickson RV, Moore JP, Roel JP. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:425-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 801] [Cited by in RCA: 853] [Article Influence: 34.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Varadarajulu S, Kilgore ML, Wilcox CM, Eloubeidi MA. Relationship among hospital ERCP volume, length of stay, and technical outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:338-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lee HJ, Cho CM, Heo J, Jung MK, Kim TN, Kim KH, Kim H, Cho KB, Kim HG, Han J, Lee DW, Lee YS. Impact of Hospital Volume and the Experience of Endoscopist on Adverse Events Related to Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography: A Prospective Observational Study. Gut Liver. 2020;14:257-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lauri A, Horton RC, Davidson BR, Burroughs AK, Dooley JS. Endoscopic extraction of bile duct stones: management related to stone size. Gut. 1993;34:1718-1721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/