Published online Oct 16, 2025. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v17.i10.108929

Revised: June 8, 2025

Accepted: August 20, 2025

Published online: October 16, 2025

Processing time: 161 Days and 4.6 Hours

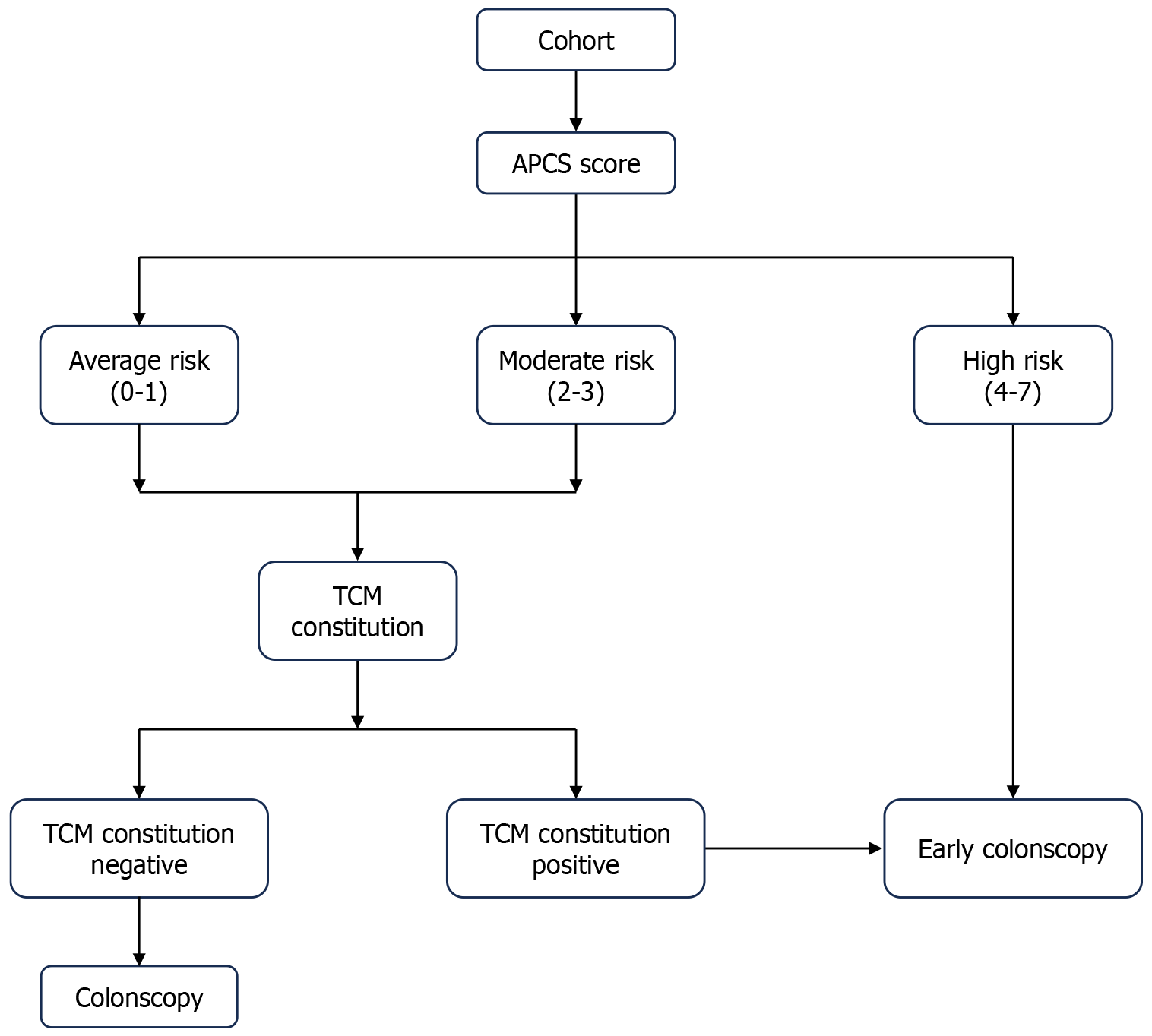

The Asia-Pacific Colorectal Screening (APCS) score was designed with the purpose of distinguishing individuals at high risk (HR) for colorectal advanced neoplasia (AN). Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) constitution was also linked with colorectal cancer (CRC).

To integrate the APCS score with TCM constitution identification as a new algorithm to screen for CRC.

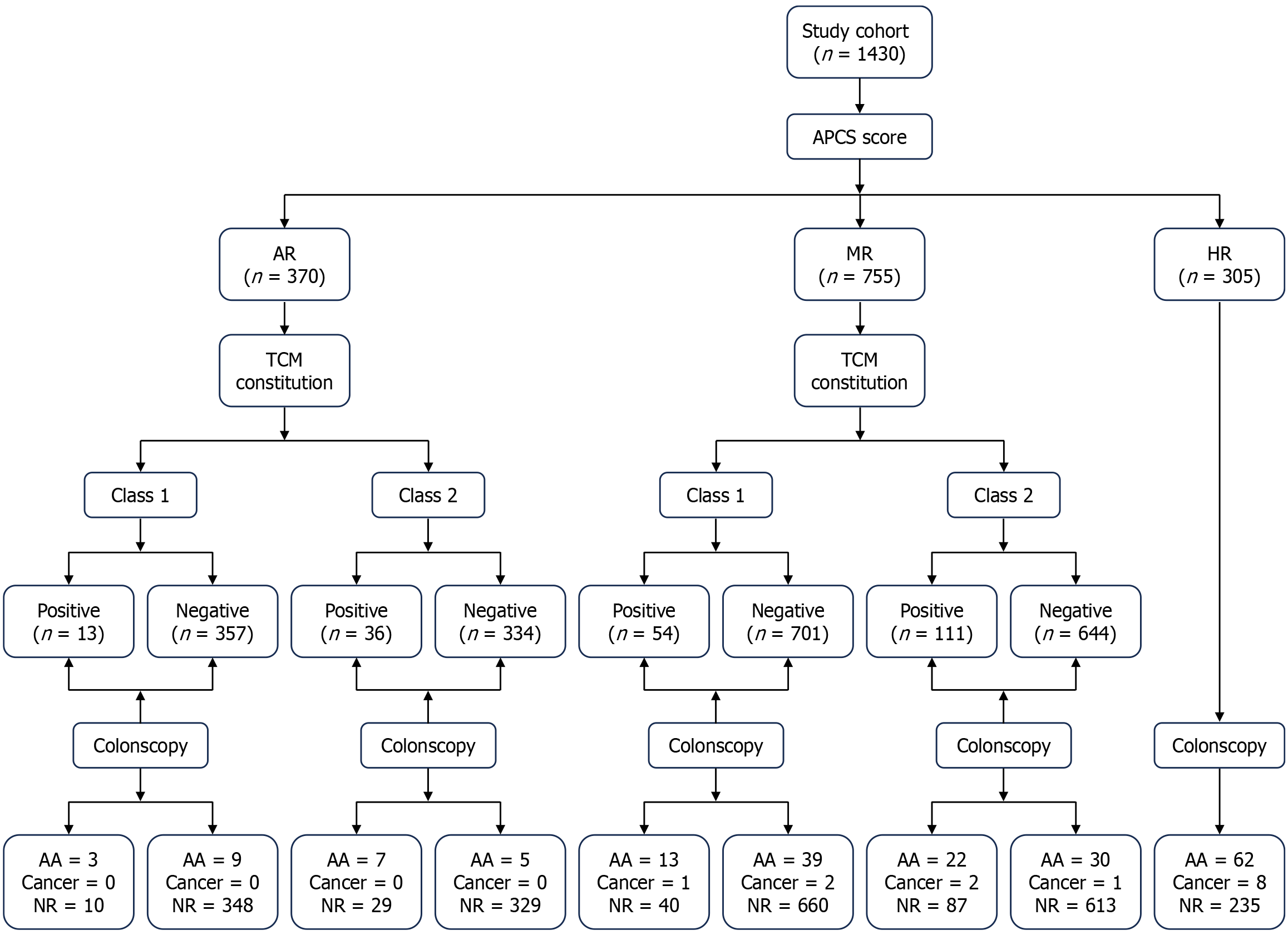

A cross-sectional multicenter study was carried out in three hospitals, enrolling 1430 patients who were asymptomatic and undergoing screening colonoscopy from 2022 to 2023. Patients were considered to have average risk, moderate risk, or HR with their APCS score. Odd ratios assessed the relationship between TCM constitution and disease progression. A TCM constitution risk score was created. The sensitivity and specificity of the new algorithm were calculated to evaluate diagnostic performance in detecting advanced adenoma (AA), CRC, and AN.

Of the 1430 patients, 370 (25.9%) were categorized as average risk, 755 (52.8%) as moderate risk, and 305 (21.3%) as HR. Using the combined APCS score and the TCM constitution (damp-heat, qi-deficiency, yang-deficiency, phlegm-dampness, and inherited special constitution as positive) algorithm, 72.2% of patients with AA and 73.7% of patients with AN were detected. Compared with the APCS score alone, the new algorithm significantly improved the sensitivity for screening AA [72.2%, 95% confidence interval (CI): 64.4%-80.0% vs 49.2%, 95%CI: 40.5%-57.9%] and AN (73.7%, 95%CI: 66.4%-81.1% vs 51.1%, 95%CI: 42.7%-59.5%).

The combination of APCS and TCM constitution identification questionnaires was valuable in identifying Chinese individuals who were asymptomatic for colorectal screening prioritization.

Core Tip: Based on this cross-sectional multicenter study, we found that the combination of the Asia-Pacific Colorectal Screening score and traditional Chinese medicine constitution identification was more convenient and cost-effective compared with the Asia-Pacific Colorectal Screening score alone and was suitable for Chinese individuals. Patients with high-risk colorectal neoplasm could be screened early using the new method to reduce the burden of colonoscopy.

- Citation: Liu QH, Hou Y, Li S, Gu YL, Huang CX, Kang Q, Fan YJ, Zhu LQ, Sun L, Men RC, Li XY, Wang H, Wei XY, Sun ZG, He YQ. Risk scoring system combined with traditional Chinese medicine constitution identification improves colorectal advanced neoplasms screening effectiveness for early colonoscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2025; 17(10): 108929

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v17/i10/108929.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v17.i10.108929

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) theory has continued to advance and expand since the 1970s, and the exploration and advancement of TCM constitution theory has reached a new stage. Scholars increasingly focus on exploring the correlation between cancer and TCM constitution, aiming to uncover the potential role of early identification of different constitutions in cancer prevention and treatment.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common cancers and ranks third in incidence and second in mortality worldwide[1]. CRC typically progresses following the adenoma-cancer order with the entire process generally lasting 5-10 years. There is compelling evidence to indicate that screening for CRC improves survival[2,3].

Recently, there has been an increase in the use of noninvasive screening methods for CRC detection due to the challenges in organizing widespread population screening programs using colonoscopy. It was reported that the increase in stool testing could counteract the decrease in colonoscopy[4]. The fecal immunochemical test (FIT) is still recommended as a screening test due to its high participation rate and high sensitivity (SEN)[5]. The combination of the Asia-Pacific Colorectal Screening (APCS) score and FIT could be an effective method for testing patients with CRC and advanced adenoma (AA) and to decrease the colonoscopy workload[6]. The multitarget stool DNA test is also a modality with high SEN for detecting early-stage CRC[7]. However, fecal testing may also encounter low compliance due to its unesthetic appearance. Hence, the development of a more convenient means of motivating subjects who are asym

It is known that body constitution plays a fundamental role in the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of disease[8]. Research has shown that TCM constitution is related to diseases such as age-related cognitive decline[9], body mass index types[10], cancer-related adverse events[11,12], etc. To date existing national studies have explored the distribution characteristics of TCM constitution and the predisposition constitution in patients with precancerous lesions and CRC. Yang-deficiency was found to be a risk factor for CRC and precancerous lesions[13]. A meta-analysis showed that the main constitution types for colorectal polyps were damp-heat, phlegm-dampness, yang-deficiency, and qi-deficiency constitutions. Damp-heat and qi-deficiency constitutions may be risk factors for the progression of colorectal adenomatous polyps[14]. If we can diagnose and intervene in the constitution status of patients, this could prevent the onset of disease and pathological changes and promote non-disease treatment[15]. In addition, TCM constitution could be judged preliminarily using a questionnaire.

This study analyzed the screening performance for colorectal neoplasms using the APCS score in conjunction with various combinations of TCM constitutions with an identification risk scoring system.

A total of 1430 subjects who were asymptomatic from Wuhai Hospital of Traditional Chinese and Mongolian Medicine, Beijing Chest Hospital and Taizhou Fourth People’s Hospital and underwent colonoscopy were enrolled in this study between 2022 and 2023. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Taizhou Fourth People’s Hospital, approval No. 2023-EC/TZFH-035, Wuhai Hospital of Traditional Chinese, and Mongolian Medicine, and Beijing Chest Hospital in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki’s ethical guidelines. All the participants provided informed consent.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Outpatients who were > 40 years old; (2) Subjects who could undergo colonoscopy; and (3) Subjects who understood the informed consent form and voluntarily signed it. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) A history of colorectal disease (including CRC or inflammatory bowel disease); (2) Those who had undergone colon cancer screening or examination in the past 5 years (such as colonoscopy, barium enema examination, colon CT imaging or magnetic resonance imaging examination); (3) Serious diseases such as cardiopulmonary insufficiency, etc, which may increase the risks of colonoscopy; (4) History of colorectal surgery; and (5) Subjects who did not accept screening and/or follow-up. The APCS and TCM constitution identification questionnaires were completed before colonoscopy, and the specific process is shown in Figures 1 and 2.

According to accepted criteria, lesions with a villous component > 25% or with high-grade intramucosal neoplasia (equivalent to previous severe dysplasia and carcinoma in situ/intramucosal carcinoma) or with a maximum diameter of ≥ 10 mm in adenomatous polyps were considered to be AA (at least one of the criteria was fulfilled). Advanced neoplasm (AN) included AA and colon cancer.

This study used the APCS score[16], which ranged between 0 and 7 depending on age, sex, family history of CRC in a first-degree relative, and smoking history. Details of the scores are shown in Supplementary Table 1 (age: < 50 years: 0; 50-69: 2; ≥ 70: 3. Sex: Female: 0; male: 1. Family history of CRC in a first-degree relative: Absent: 0; present: 2. Smoking history: No: 0; current or past: 1). In order to determine the risk level of these subjects, three risk levels were defined: Average risk (AR): A score of 0-1; moderate risk (MR): 2-3; high risk (HR): 4-7.

All subjects completed the TCM constitution identification questionnaire. The TCM constitution was determined by a previous report[17]. This questionnaire included nine types of body constitutions, including balanced, blood stasis, qi-deficiency, qi stagnation, yang-deficiency, yin-deficiency, phlegm-dampness, damp-heat, and an inherited special constitution. It required the computed original score when completing all the answers. Following that, the converted score was computed using the formula, and the individual’s TCM constitution was determined.

The SPSS16.0 software was used to perform the statistical analysis. The normally distributed measurement data are presented as mean ± SD. Categorical variables were presented as number and proportion, and the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare groups. To evaluate the impact of TCM constitution on disease progression, univariate logistic regression was performed. Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated for each constitution. For constitutions showing a statistically significant association, a corresponding risk score weight was derived by halving the OR and rounding it to the nearest whole number. Individuals were then classified based on their total risk score: Those with a score ≥ 5 were assigned to class 1 positive while those with a score ≥ 3 were assigned to class 2 positive. To account for multiple comparisons among the three risk groups (AR, MR, and HR), we applied Bonferroni correction to adjust the P values. To explore the diagnostic performance for AA, CRC, and AN, we calculated the SEN, specificity, and positive predictive value expressed as a proportion with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). P values were based on two-sided statistical tests. Statistical significance was determined at 0.05.

Three sites were included in this study, and 1430 subjects who were asymptomatic completed the questionnaires. A summary of the demographic characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1 and Supplementary Tables 2 and 3. The average age of the patients was 54.4 years (SD = 9.1 years), mean body mass index was 23.7 kg/m2 (SD = 2.8 kg/m2), and 818 (57.2%) patients were male. Twenty-seven patients (1.9%) had a family history of CRC in a first-degree relative, and 974 (68.1%) were nonsmokers. According to the APCS score, 370 (25.9%) were categorized as AR, 755 (52.8%) as MR, and 305 (21.3%) as HR. Based on colonoscopies and biopsies, 126 (8.8%) were diagnosed with AA, and 11 (0.8%) were diagnosed with CRC. The number and proportion of TCM constitutions are shown in Table 1. One thousand and forty patients (72.7%) had Pinghe constitutions, and the others were biased constitutions.

| Characteristics | n (%) |

| Age (year), mean ± SD | 54.4 ± 9.1 |

| Age ≤ 55 | 836 (58.5) |

| Age > 55 | 594 (41.5) |

| BMI upon admission (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 23.7 ± 2.8 |

| Normal and low (BMI < 24.0) | 845 (59.1) |

| Overweight (BMI: 24.0-27.9) | 494 (34.5) |

| Obese (BMI ≥ 28.0) | 91 (6.4) |

| CRC family history | 27 (1.9) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 818 (57.2) |

| Female | 612 (42.8) |

| Hospital | |

| Beijing Chest Hospital | 93 (6.5) |

| Wuhai Hospital | 238 (16.6) |

| Taizhou Fourth People’s Hospital | 1099 (76.9) |

| Cigarette smoking | |

| Nonsmoker | 974 (68.1) |

| Past smoker | 152 (10.6) |

| Current smoker | 304 (21.3) |

| TCM constitution | |

| Yang-deficiency | 68 (4.8) |

| Inherited special | 16 (1.1) |

| Balanced | 1040 (72.7) |

| Damp-heat | 78 (5.5) |

| Qi-deficiency | 57 (4.0) |

| Qi-stagnation | 26 (1.8) |

| Phlegm-dampness | 71 (5.0) |

| Blood stasis | 27 (1.9) |

| Yin-deficiency | 47 (3.3) |

| APCS | |

| Average risk | 370 (25.9) |

| Moderate risk | 755 (52.8) |

| High risk | 305 (21.3) |

| CRC findings | |

| Negative | 1293 (90.4) |

| Advanced adenoma | 126 (8.8) |

| CRC | 11 (0.8) |

There were significantly more AAs in patients with MR compared with patients with AR patients (3.6% vs 0.8%, P = 0.013 for AA). In addition significantly more AAs and CRCs were found in patients with HR than in patients with MR (4.3% vs 3.6%, P < 0.001 for AA; 0.6% vs 0.2%, P = 0.004 for CRC). No CRC was identified in the AR group. CRC was found in three subjects in the MR group and in eight subjects in the HR group (Table 2).

| Lesion characteristics | AR | MR | HR | P value | OR (95%CI) |

| Negative | 358 (25.0) | 700 (49.0) | 235 (16.4) | MR vs AR: 0.007 | MR vs AR: 0.4 (0.2-0.8) |

| HR vs AR: < 0.001 | HR vs AR: 0.1 (0.0-0.2) | ||||

| HR vs MR: < 0.001 | HR vs MR: 0.3 (0.2-0.4) | ||||

| Advanced adenoma | 12 (0.8) | 52 (3.6) | 62 (4.3) | MR vs AR: 0.013 | MR vs AR: 2.2 (1.2-4.2) |

| HR vs AR: < 0.001 | HR vs AR: 7.6 (4.0-14.4) | ||||

| HR vs MR: < 0.001 | HR vs MR: 3.4 (2.3-5.1) | ||||

| Colorectal cancer | 0 (0) | 3 (0.2) | 8 (0.6) | MR vs AR: 0.555 | MR vs AR: - |

| HR vs AR: 0.005 | HR vs AR: - | ||||

| HR vs MR: 0.004 | HR vs MR: 6.8 (1.8-25.6) |

Univariate logistic regression was performed for each TCM constitution (Table 3). The analysis showed that all the biased TCM constitutions except for Yin-xu constitution (P = 0.057) were associated with disease progression. According to the OR value, points were then allocated to each TCM constitution for AN as follows (Table 4): Balanced (0); yin-deficiency (1); qi-stagnation (2); blood stasis (2); yang-deficiency (3); phlegm-dampness (3); inherited special constitution (3); damp-heat (5); and qi-deficiency (5). For further study, we established two different combination patterns (class 1 and class 2) of TCM constitution according to the risk score. Class 1 was defined as damp-heat and qi-deficiency constitutions, which were positive, while other constitutions were negative. Class 2 was defined as damp-heat, qi-deficiency, yang-deficiency, phlegm-dampness, and inherited special constitutions and were positive while other constitutions were negative.

| TCM constitution | OR (95%CI) | P value |

| Yang-deficiency | 5.6 (2.9-10.8) | < 0.001 |

| Damp-heat | 10.8(6.2-18.8) | < 0.001 |

| Qi-deficiency | 9.2 (4.8-17.4) | < 0.001 |

| Qi-stagnation | 3.9 (1.3-11.9) | 0.015 |

| Phlegm-dampness | 6.8 (3.7-12.6) | < 0.001 |

| Blood stasis | 4.9 (1.8-13.6) | 0.002 |

| Yin-deficiency | 2.6 (1.0-6.8) | 0.057 |

| Inherited special | 5.0 (1.4-18.1) | 0.015 |

| TCM constitution | Score |

| Yang-deficiency | 3 |

| Damp-heat | 5 |

| Qi-deficiency | 5 |

| Qi stagnation | 2 |

| Phlegm-dampness | 3 |

| Blood stasis | 2 |

| Yin-deficiency | 1 |

| Inherited special | 3 |

| Balanced | 0 |

The distribution of lesion characteristics and TCM constitutions in the AR and MR groups are shown in Table 5. All subjects with CRC were in the MR group. Among them, one positive TCM constitution result was in class 1, and two positive TCM constitution results were in class 2. In accordance with the results, using TCM constitution identification for patients with AR and MR and colonoscopy for patients with HR could miss the diagnosis of CRC in 2 out of 3 patients (class 1) or 1 out of 3 patients (class 2).

| Lesion characteristics | Average risk | Moderate risk | ||||||||

| n (%) | Class 1 | Class 2 | n (%) | Class 1 | Class 2 | |||||

| TCM constitution (negative) | TCM constitution (positive) | TCM constitution (negative) | TCM constitution (positive) | TCM constitution (negative) | TCM constitution (positive) | TCM constitution (negative) | TCM constitution (positive) | |||

| Negative | 358 (96.8) | 348 | 10 | 329 | 29 | 700 (92.7) | 660 | 40 | 613 | 87 |

| Advanced adenoma | 12 (3.2) | 9 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 52 (6.9) | 39 | 13 | 30 | 22 |

| Colorectal cancer | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (0.4) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 370 (100.0) | 357 | 13 | 334 | 36 | 755 (100.0) | 701 | 54 | 644 | 111 |

Based on the APCS score combined with the TCM constitution identification score, the SEN of diagnoses in patients with AA, CRC, and AN were all significantly increased compared with the APCS score alone (Table 6). The SEN of APCS combined with class 2 for AN was 73.7% (95%CI: 66.4%-81.1%), the SEN of APCS combined with class 1 for AN was 63.5% (95%CI: 55.4%-71.6%) while the SEN of APCS for AN was 51.1% (95%CI: 42.7%-59.5%). The SEN of APCS plus class 2 for CRC (90.9%; 95%CI: 73.9%-107.9%) was higher than the SEN of APCS plus class 1 (81.8%; 95%CI: 59.0%-104.6%) and APCS alone (72.7%; 95%CI: 46.4%-99.0%). The SEN of APCS plus class 2 for AA (72.2%; 95%CI: 64.4%-80.0%) was higher than the SEN of APCS plus class 1 (61.9%; 95%CI: 53.4%-70.4%) and APCS alone (49.2%; 95%CI: 40.5%-57.9%). Based on the APCS combined with the class 2 TCM constitution algorithm, the specificity for diagnosing AA, CRC, and AN was 72.3% (95%CI: 69.9%-74.7%), 68.9% (95%CI: 66.4%-71.3%) and 72.9% (95%CI: 70.4%-75.3%), respectively. The predictive value was 20.1% (95%CI: 16.4%-23.8%), 2.2% (95%CI: 0.9%-3.6%), and 22.3% (95%CI: 18.5%-26.2%), respectively.

| Characteristics | AA (95%CI) | Cancer (95%CI) | AA + cancer (95%CI) | ||||||

| SEN % | SPE % | PPV % | SEN % | SPE % | PPV % | SEN % | SPE % | PPV % | |

| APCS | 49.2 (40.5-57.9) | 81.4 (79.3-83.5) | 20.3 (15.8-24.8) | 72.7 (46.4-99.0) | 79.1 (77.0-81.2) | 2.6 (0.8-4.4) | 51.1 (42.7-59.5) | 81.8 (79.7-83.9) | 23 (18.2-27.7) |

| APCS plus class 1 + | 61.9a (53.4-70.4) | 77.5 (75.2-79.7) | 21 (16.8-25.1) | 81.8 (59.0-104.6) | 74.4 (72.1-76.7) | 2.4 (0.9-4.0) | 63.5a (55.4-71.6) | 78 (75.7-80.2) | 23.4 (19.1-27.7) |

| APCS plus class 2 + | 72.2b (64.4-80.0) | 72.3 (69.9-74.7) | 20.1 (16.4-23.8) | 90.9 (73.9-107.9) | 68.9 (66.4-71.3) | 2.2 (0.9-3.6) | 73.7b (66.4-81.1) | 72.9 (70.4-75.3) | 22.3 (18.5-26.2) |

This study demonstrated that using the combination of the APCS score and TCM constitution identification and colonoscopy for CRC screening was not only cost-effective but also convenient, leading to high patient compliance rates. The SEN of the APCS score combined with TCM constitution was 90.9% in detecting invasive cancer and 72.2% in detecting AA. This study was the first to incorporate TCM constitution identification into CRC screening and demonstrate its effectiveness.

Colonoscopy is the gold standard in CRC screening. Patients who underwent colonoscopy screening had a lower risk of CRC at 10 years[18]. Nevertheless, colonoscopy requires strict bowel preparation and is an invasive procedure that can deter patients due to financial, psychosocial, and procedural barriers[19]. Additionally, there is a risk of complications such as bleeding and perforation associated with colonoscopy[20], further impacting patient compliance. Moreover, considering the lack of colonoscopy resources and uneven medical infrastructure in certain Asian regions, it is not a suitable method for CRC screening in large populations. A large-scale CRC screening program in China showed a low participation rate in colonoscopy screening among patients who were HR[21]. Therefore, there is a critical need to explore alternative CRC screening strategies that are more accessible, less invasive, and better suited for widespread implementation among diverse populations.

The APCS score stands as one of the most widely utilized questionnaires for assessing CRC risk. It can be used for risk stratification based on factors such as age, gender, family history, and smoking and predicts the likelihood of developing colorectal AN[16]. In previous studies the APCS score has proven effective for screening CRC in a prioritized asymptomatic Chinese population[22]. In our study we used the APCS score to stratify patients. The SEN for detecting CRC was 72.7%. However, the SEN for detecting AA (49.2%) and AN (51.1%) was low and urged us to find a new combined modality to improve the SEN.

Recently, there has been a surge in the development of noninvasive tests for CRC screening, such as the stool DNA test and FIT. The SEN for detecting AN was 67.5% using APCS with FIT[6]. A study showed that the SEN for detecting AN could be improved when pairing APCS with stool DNA compared with APCS with FIT[23]. However, due to the need to collect stools and the large populations in China, we aimed to develop a more convenient method that does not require the retention of biological samples and could be implemented in large populations combined with the APCS score based on China’s national conditions.

The risk of CRC varies among individuals with different TCM constitutions. TCM constitution identification could be used as a tool to estimate an individual’s risk of CRC[24]. Our study calculated the risk score based on the OR value. The results showed that damp-heat and qi-deficiency constitutions had the highest score. This was followed by yang-deficiency, phlegm-dampness, and inherited special constitutions. We considered that patients with higher scores may have faster disease progression. Then, we divided patients into class 1 and class 2 based on the TCM constitution identification score and determined the diagnostic performance of different TCM constitutions combined with the APCS score.

In this study the most notable finding was that significant enhancement in the SEN for detecting AA and CRC was achieved using the combination of the APCS score with TCM constitution identification questionnaires compared with using the APCS score alone. Particularly intriguing was the observation that the SEN of the APCS score combined with TCM class 2 identification surpassed that of the APCS score combined with TCM class 1 identification. This indicated that damp-heat, qi-deficiency, yang-deficiency, phlegm-dampness, and inherited special constitutions may all be risk factors for disease acceleration. The greatest advantage observed in our study was that the combination of the APCS risk scoring system on the basis of TCM constitution identification revealed that the screening SEN of APCS was improved. Simultaneously, according to the research results, by appropriately adjusting the acquired living environment and changing the biased constitution, this can prevent CRC in advance. Additionally, this research has contributed to the promotion of TCM constitution and the integration of Chinese and Western medicine in diagnosis and treatment. TCM constitution identification only required participants to complete questionnaires, which are more convenient than a stool test and decrease the screening cost, leading to greater compliance.

There were some limitations in the study. First, the population distribution from three sites was uneven. Second, this study involved opportunistic screening, and all patients were outpatients. Thus, our conclusions do not represent the entire population. Third, this study was retrospective rather than prospective; thus, a prospective, large sample population is needed to verify our results in the future. Fourth, TCM constitution identification was determined using a questionnaire. However, the questionnaire included too much content that the patients indicated had strong subjectivity. In addition the results may have been subject to bias due to the lack of objective criteria, further affecting the conclusions.

The findings of this study demonstrated that integrating the APCS score with the TCM constitution identification score was a more effective, simple, rapid, and economical approach for identifying colorectal ANs compared with using the APCS score alone. This approach has the potential to identify a significant portion of ANs while also alleviating colonoscopy burden, making it an option for CRC screening and prevention in regions with limited resources.

We gratefully acknowledge all participants for their support.

| 1. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 68881] [Article Influence: 13776.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (202)] |

| 2. | Siegel RL, Wagle NS, Cercek A, Smith RA, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73:233-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1861] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 3. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Fedewa SA, Butterly LF, Anderson JC, Cercek A, Smith RA, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:145-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2268] [Cited by in RCA: 3368] [Article Influence: 561.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 4. | Fedewa SA, Star J, Bandi P, Minihan A, Han X, Yabroff KR, Jemal A. Changes in Cancer Screening in the US During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2215490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 35.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Onyoh EF, Hsu WF, Chang LC, Lee YC, Wu MS, Chiu HM. The Rise of Colorectal Cancer in Asia: Epidemiology, Screening, and Management. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2019;21:36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chiu HM, Ching JY, Wu KC, Rerknimitr R, Li J, Wu DC, Goh KL, Matsuda T, Kim HS, Leong R, Yeoh KG, Chong VH, Sollano JD, Ahmed F, Menon J, Sung JJ; Asia-Pacific Working Group on Colorectal Cancer. A Risk-Scoring System Combined With a Fecal Immunochemical Test Is Effective in Screening High-Risk Subjects for Early Colonoscopy to Detect Advanced Colorectal Neoplasms. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:617-625.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hanna M, Dey N, Grady WM. Emerging Tests for Noninvasive Colorectal Cancer Screening. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21:604-616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Li L, Yao H, Wang J, Li Y, Wang Q. The Role of Chinese Medicine in Health Maintenance and Disease Prevention: Application of Constitution Theory. Am J Chin Med. 2019;47:495-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sun Z, Ping P, Li Y, Feng L, Liu F, Zhao Y, Yao Y, Zhang P, Fu S. Relationships Between Traditional Chinese Medicine Constitution and Age-Related Cognitive Decline in Chinese Centenarians. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022;14:870442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Li M, Mo S, Lv Y, Tang Z, Dong J. A Study of Traditional Chinese Medicine Body Constitution Associated with Overweight, Obesity, and Underweight. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2017;2017:7361896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Deng SM, Chiu AF, Wu SC, Huang YC, Huang SC, Chen SY, Tsai MY. Association between cancer-related fatigue and traditional Chinese medicine body constitution in female patients with breast cancer. J Tradit Complement Med. 2021;11:62-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Liu Y, Pan T, Zou W, Sun Y, Cai Y, Wang R, Han P, Zhang Z, He Q, Ye F. Relationship between traditional Chinese medicine constitutional types with chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients with breast cancer: an observational study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16:451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zhao MM, Zeng B, Du M, Wang W. [Logistic Regression Analysis between Colorectal Cancer and Traditional Chinese Medicine Constitutions and Related Risk Factors]. Zhongguo Zhongxiyi Jiehe Zazhi. 2019;39:23-27. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Bian YQ, Zheng Y, Zheng PY, Ji G, You SF, Liu T. [Meta-analysis of correlation between TCM constitution and colorectal polyps]. Shanghai Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2021;55:24-32. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Wang Q. Individualized medicine, health medicine, and constitutional theory in Chinese medicine. Front Med. 2012;6:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 16. | Yeoh KG, Ho KY, Chiu HM, Zhu F, Ching JY, Wu DC, Matsuda T, Byeon JS, Lee SK, Goh KL, Sollano J, Rerknimitr R, Leong R, Tsoi K, Lin JT, Sung JJ; Asia-Pacific Working Group on Colorectal Cancer. The Asia-Pacific Colorectal Screening score: a validated tool that stratifies risk for colorectal advanced neoplasia in asymptomatic Asian subjects. Gut. 2011;60:1236-1241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | China Association of Chinese Medicine. [Classification and determination of constitution in TCM (ZYYXH/T157-2009)]. Shijie Zhongxiyi Jiehe Zazhi. 2009;4:303-304. |

| 18. | Bretthauer M, Løberg M, Wieszczy P, Kalager M, Emilsson L, Garborg K, Rupinski M, Dekker E, Spaander M, Bugajski M, Holme Ø, Zauber AG, Pilonis ND, Mroz A, Kuipers EJ, Shi J, Hernán MA, Adami HO, Regula J, Hoff G, Kaminski MF; NordICC Study Group. Effect of Colonoscopy Screening on Risks of Colorectal Cancer and Related Death. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:1547-1556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 517] [Article Influence: 129.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 19. | Shaukat A, Levin TR. Current and future colorectal cancer screening strategies. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;19:521-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 314] [Article Influence: 78.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Helsingen LM, Kalager M. Colorectal Cancer Screening - Approach, Evidence, and Future Directions. NEJM Evid. 2022;1:EVIDra2100035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 21. | Chen H, Li N, Ren J, Feng X, Lyu Z, Wei L, Li X, Guo L, Zheng Z, Zou S, Zhang Y, Li J, Zhang K, Chen W, Dai M, He J; group of Cancer Screening Program in Urban China (CanSPUC). Participation and yield of a population-based colorectal cancer screening programme in China. Gut. 2019;68:1450-1457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 262] [Article Influence: 37.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Li W, Zhang L, Hao J, Wu Y, Lu D, Zhao H, Wang Z, Xu T, Yang H, Qian J, Li J. Validity of APCS score as a risk prediction score for advanced colorectal neoplasia in Chinese asymptomatic subjects: A prospective colonoscopy study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e5123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Xu J, Rong L, Gu F, You P, Ding H, Zhai H, Wang B, Li Y, Ma X, Yin F, Yang L, He Y, Sheng J, Jin P. Asia-Pacific Colorectal Screening Score Combined With Stool DNA Test Improves the Detection Rate for Colorectal Advanced Neoplasms. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21:1627-1636.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sang XX, Wang ZX, Liu SY, Wang RL. Relationship Between Traditional Chinese Medicine(TCM)Constitution and TCM Syndrome in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Diseases. Chin Med Sci J. 2018;33:114-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/