Published online Dec 18, 2017. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v9.i35.1286

Peer-review started: July 20, 2017

First decision: September 7, 2017

Revised: September 19, 2017

Accepted: October 30, 2017

Article in press: October 30, 2017

Published online: December 18, 2017

Processing time: 141 Days and 18.2 Hours

To investigate the prevalence, clinicopathological characteristics and surgical outcomes of occult hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection (OBI) in patients with non-B, non-C (NBNC) hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

This study retrospectively examined the cases of 78 NBNC patients with curative resection for HCC for whom DNA could be extracted from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue. OBI was determined by the HBV-DNA amplification of at least two different sets of primers by TaqMan real-time polymerase chain reaction. Possibly carcinogenetic factors such as alcohol abuse, diabetes mellitus, obesity and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) were examined. Surgical outcomes were evaluated according to disease-free survival (DFS), overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS).

OBI was found in 27/78 patients (34.6%) with NBNC HCC. The OBI patients were significantly younger than the non-OBI cases at the time of surgery (average age 63.0 vs 68.1, P = 0.0334) and the OBI cases overlapped with other etiologies significantly more frequently compared to the non-OBI cases (P = 0.0057). OBI had no impact on the DFS, OS or DSS. Only tumor-related factors affected these surgical outcomes.

Our findings indicate that OBI had no impact on surgical outcomes. The surgical outcomes of NBNC HCC depend on early tumor detection; this reconfirms the importance of a periodic medical examination for individuals who have NBNC HCC risk factors.

Core tip: We analyzed the occult hepatitis B virus infection (OBI) status of 78 cases of non-B, non-C hepatocellular carcinoma (NBNC HCC). OBI was found in 27/78 patients (34.6%). The OBI patients were significantly younger than the non-OBI patients at the time of surgery, and the OBI cases were frequently overlapped with other etiologies. OBI had no impact on surgical outcomes. Only tumor-related factors affected the surgical outcomes. The surgical outcomes of NBNC HCC thus depend in part on the early detection of the tumor.

- Citation: Koga H, Kai K, Aishima S, Kawaguchi A, Yamaji K, Ide T, Ueda J, Noshiro H. Occult hepatitis B virus infection and surgical outcomes in non-B, non-C patients with curative resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol 2017; 9(35): 1286-1295

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v9/i35/1286.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v9.i35.1286

Although the most major risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) are hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, the prevalence of non-B, non-C (NBNC) HCC patients who are negative for both hepatitis C antibody (HCVAb) and hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) has gradually increasing. In a 2010 Japanese survey, the prevalence of NBNC HCC were 24.1% of all HCC patients[1].

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD)[2] and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)/non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)[3,4] are well-known etiologies of NBNC HCC. Other known etiologies of NBNC HCC include hemochromatosis[5], Budd-Chiari syndrome[6], metabolic disease, autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, parasitic disease, congestive disease and unknown etiology[7]. Occult HBV infection (OBI) was also recognized as one of the risk factors for the development of HCC[8,9]. OBI is considered one of the possible phases in the natural history of chronic HBV infection[10], and it reflects the persistence of HBV genomes in the hepatocytes of individuals who test negative for HBsAg[11]. The gold standard to diagnose OBI is the detection of HBV DNA in the hepatocytes by highly sensitive and specific techniques such as real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the sets of specific primers for different HBV genomic regions[11-14].

The virology and pathogenesis of OBI have been well investigated[15,16], and many epidemiological and molecular biological studies have addressed that OBI is an important risk factor for developing HCC[9]. However, the clinical characteristics and surgical outcomes of OBI-associated HCC have not been well-investigated. We could not find any study that investigated in detail a surgical series of OBI-associated HCC. It is quite important to determine the clinical characteristics and surgical outcomes of OBI-associated HCC among cases of NBNC HCC or HCV-associated HCC because different etiologies of HCC may modulate the clinical characteristics and outcomes, thereby requiring different preventive and therapeutic strategies.

Our aim in the present study was to clarify the prevalence, clinicopathological characteristics and surgical outcomes in patients with OBI-associated HCC in our surgical series of NBNC HCC patients. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the surgical outcomes in OBI-associated NBNC HCC.

Initially, 477 patients with HCC who underwent curative surgical resection for the primary lesion at Saga University Hospital between 1984 and 2012 were enrolled the study. All patients enrolled in this study had no lymph node metastasis or distant metastasis at the time of surgery. Of these, 83 cases of NBNC HCC were identified and subjected to DNA extraction from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue blocks. These 83 NBNC HCC cases were same population of previous our study[17]. We retrospectively examined a final total of 78 cases of NBNC HCC (in the other five cases, DNA was unavailable). Written informed consent for the use of their liver tissues and clinical information was obtained from all patients. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine at Saga University (Approval No. 27-18).

Sections cut from FFPE tissue blocks of noncancerous liver tissue were used. The NucleoSpin® DNA FFPE system (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan) was used to extract the nucleic acid from liver tissues (< 10 mg) per the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA was eluted in 20 μL of Tris Borate EDTA (TBE) buffer. The amount and quality of extracted DNA was confirmed by NanoDrop® (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Yokohama, Japan).

The regions of HBs, hepatitis B core (HBc), and hepatitis B x (HBx) in the HBV DNA were analyzed by TaqMan real-time PCR per the manufacturer’s guidelines (TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The oligonucleotide primers and probes which were specific for the S, X and C regions of HBV were as described by Kondo et al[18]. Plasmid pBRHBadr72 (full-length HBV DNA) was used as an internal standard. The detection limit of our TaqMan real-time PCR was 100 copies/mL. Only the cases in which HBV DNA was detected by the TaqMan real-time PCR using at least two different sets of primers were considered to exhibit OBI[11].

To analyze the relationships between OBI and other etiologies of NBNC HCC, we also investigated the patients’ alcohol consumption status and metabolic factors such as diabetes mellitus, obesity and NASH. The patients who were clinically diagnosed as having diabetes mellitus were categorized as diabetes mellitus group. A body mass index (BMI) > 25 kg/m2 in both genders was defined as obesity. We defined an alcohol abuse as a daily ethanol consumption of > 40 g for men and > 20 g for women.

To pathologically assess the degree of fibrosis in noncancerous liver tissues, we used the new Inuyama classification system which is widely used in Japan: F0, no fibrosis; F1, portal fibrosis widening; F2, portal fibrosis widening with bridging fibrosis; F3, bridging fibrosis plus lobular distortion; and F4, cirrhosis[19]. The diagnoses of NASH were pathologically confirmed. These histopathological analysis and classification were performed by two pathologists (Keita Kai and Shinichi Aishima).

All statistical analyses were supervised by a statistician (Atsushi Kawaguchi). The statistical analysis was performed using JMP ver. 12 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and SAS software ver. 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± SD and were compared using the Student’s t test. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Disease-free survival (DFS), overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) was determined according to our previous report[17]. The uni- and multi-variate analyses were performed using a Cox proportional hazards model. To adjust the potential covariates for the comparison of OBI status in the multivariate analysis, age, gender and OBI status were always kept in the model and other parameters were selected by the stepwise procedure with the P-value threshold of 0.2. P-values < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

The OBI status of the patients is summarized in Table 1. Twenty-seven patients (34.6%) were categorized as having an OBI in this study. The details of HBV-DNA amplification were HBc lesion, 23 cases (29.4%); HBs lesion, 50 cases (64.1%); and HBx lesion, 32 cases (41.0%). The number of cases with amplification of at least one lesion was 64 cases (82.1%).

| Occult HBV infection (%) | |

| (+) | 27 (34.6) |

| (−) | 51 (65.4) |

| Details of HBV amplification | |

| HBc lesion (%) | 23 (29.4) |

| HBs lesion (%) | 50 (64.1) |

| HBx lesion (%) | 32 (41.0) |

| Amplification of at least one lesion (%) | 64 (82.1) |

Table 2 demonstrates the summary of the clinicopathological features. The 78 patients with NBNC HCC were consisted of 61 men (78.2%) and 17 women (21.8%). The mean age at the time of surgery was 66.3 years. Alcohol abuse was identified in 19 patients (24.4%). Twenty-seven patients (34.6%) had diabetes mellitus and obese was found in 24 patients (30.8%). NASH was pathologically confirmed in eight patients (10.3%).

| Total cases (n = 78) | OBI (n = 27) | Non-OBI (n = 51) | P1 | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 66.3 ± 11.9 | 63.0 ± 17.0 | 68.1 ± 7.6 | 0.0334 |

| Gender (%) | 0.6066 | |||

| Male | 61 (78.2) | 22 (81.5) | 39 (79.5) | |

| Female | 17 (21.8) | 5 (18.5) | 12 (20.5) | |

| Alcohol abuse (%) | 0.8151 | |||

| (+) | 19 (24.4) | 7 (25.9) | 12 (23.5) | |

| (-) | 59 (75.6) | 20 (74.1) | 39 (77.1) | |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 0.106 | |||

| (+) | 27 (34.6) | 10 (37.0) | 17 (33.3) | |

| (-) | 51 (65.4) | 17 (63.0) | 34 (66.7) | |

| Obesity (%) | 0.4966 | |||

| (+) | 24 (30.8) | 7 (25.9) | 17 (33.3) | |

| (-) | 54 (69.2) | 20 (74.1) | 34 (66.7) | |

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 22.7 ± 4.56 | 22.1 ± 3.67 | 23.1 ± 4.97 | 0.3537 |

| Size (mean ± SD), mm | 64.2 ± 41.8 | 72.7 ± 45.6 | 59.8 ± 39.4 | 0.1955 |

| Solitary/multiple (%) | 0.8959 | |||

| Solitary | 47 (60.3) | 16 (59.3) | 31 (60.8) | |

| Multiple | 31 (39.7) | 11 (40.7) | 20 (39.2) | |

| Vp (%) | 0.7217 | |||

| (+) | 31 (39.7) | 10 (37.0) | 21 (41.2) | |

| (-) | 47 (60.2) | 17 (60.3) | 30 (58.8) | |

| Liver fibrosis (%) | 0.2851 | |||

| F0-2 | 44 (56.4) | 13 (48.2) | 31 (60.8) | |

| F3-4 | 34 (43.6) | 14 (51.8) | 20 (39.2) | |

| NASH (%) | 0.007 | |||

| (+) | 8 (10.3) | 0 | 8 (15.7) | |

| (−) | 70 (89.7) | 27 | 43 (84.3) | |

| No. of etiologies | 0.00572 | |||

| Single | 38 (48.7) | 11 (40.7) | 27 (52.9) | |

| Multiple | 25 (32.1) | 16 (59.3) | 9 (17.7) | |

| Unknown | 15 (19.2) | 0 | 15 (29.4) |

We compared the OBI cases (n = 27) with the non-OBI cases (n = 51) regarding clinicopathologic factors (age, gender, alcohol abuse, diabetes mellitus, obesity, BMI, tumor size, solitary/multiple, portal vein invasion, degree of background liver fibrosis, NASH and number of etiologies). Significant differences were observed in age, NASH and the number of etiologies. The OBI patients were significantly younger than the non-OBI patients at the time of surgery (P = 0.0334): 63.0 ± 17.0 and 68.1 ± 7.6 years (mean age ± SD), respectively. All eight NASH cases were non-OBI cases (P = 0.007). The OBI patients had multiple etiologies for HCC significantly more frequently compared to the non-OBI patients, and high significance was observed even in the analysis excluding etiology-unknown cases (P = 0.0057).

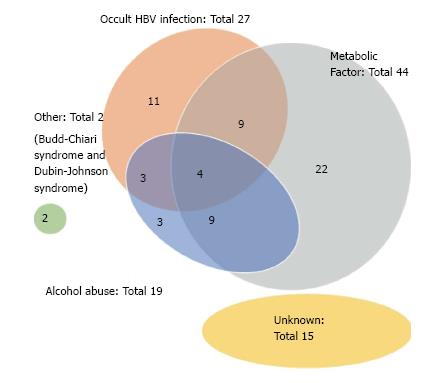

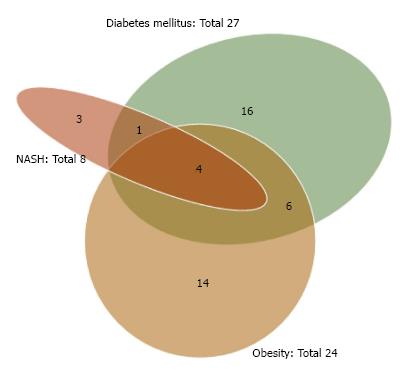

As shown in Table 2, the etiologies of our NBNC HCC cases consisted of 38 (48.7%) single-etiology cases, 25 (32.1%) multiple-etiology cases, and 15 (19.2%) unknown-etiology cases. The Venn diagram for the etiologies of NBNC HCC is given as Figure 1. OBI and alcohol abuse were frequently associated with other etiologies. The Venn diagram for the metabolic factors (obesity, diabetes mellitus and NASH) is given as Figure 2. NASH was frequently associated with other metabolic factors.

Table 3 demonstrates the results of the uni- and multivariate analyses for DFS by Cox’s proportional hazards model. The significant factors which correlated with DFS by the univariate analyses were portal vein invasion, T factor of TMN classification, and multiple tumors at the time of surgery (P = 0.0013, P = 0.0006 and P = 0.0002, respectively). The factors significantly correlated with DFS by the multivariate analysis were portal vein invasion (P = 0.0217) and multiple tumor (P = 0.0499). No patient had undergone adjuvant therapy after curative surgery until recurrence.

| Characteristic | n | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| HR (95%CI) | P-value | HR (95%CI) | P-value | ||

| Age | 0.316 | 0.1007 | |||

| ≤ 69 | 39 | 1 | 1 | ||

| > 69 | 39 | 0.74 (0.40-1.33) | 0.58 (0.30-1.11) | ||

| Gender | 0.4847 | 0.298 | |||

| Female | 17 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Male | 61 | 0.78 (0.41-1.60) | 0.66 (0.31-1.41) | ||

| Occult HBV infection | 0.8739 | 0.7096 | |||

| Absent | 51 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Present | 27 | 1.05 (0.55-1.93) | 1.13 (0.59-2.17) | ||

| Alcohol abuse | 0.2752 | ||||

| Absent | 59 | 1 | |||

| Present | 19 | 0.66 (0.28-1.35) | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.8853 | ||||

| Absent | 51 | 1 | |||

| Present | 27 | 0.95 (0.49-1.78) | |||

| NASH | 0.6226 | ||||

| Absent | 70 | 1 | |||

| Present | 8 | 1.25 (0.47-2.75) | |||

| Obesity | 0.7641 | ||||

| Absent | 54 | 1 | |||

| Present | 24 | 1.10 (0.57-2.02) | |||

| Fibrosis | 0.1477 | 0.2273 | |||

| F0-2 | 44 | 1 | 1 | ||

| F3, 4 | 34 | 1.54 (0.86-2.80) | 1.54 (0.78-2.81) | ||

| Vp | 0.0013 | 0.0217 | |||

| Absent | 47 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Present | 31 | 2.90 (1.53-5.50) | 2.52 (1.15-5.50) | ||

| T12/T34 | 0.0006 | 0.4074 | |||

| T12 | 38 | 1 | 1 | ||

| T34 | 40 | 3.14 (1.62-6.43) | 1.57 (0.53-4.67) | ||

| Solitary/multiple | 0.0002 | 0.0499 | |||

| Solitary | 47 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Multiple | 31 | 3.23 (1.73-6.14) | 2.32 (0.99-5.42) | ||

The results of the univariate and multivariate analyses for OS are summarized in Table 4. Only the factors of portal vein invasion (P = 0.022) and multiple tumors (P = 0.0334) correlated with OS by the univariate analyses. The multivariate analysis for OS indicated only one significant correlation of portal vein invasion (P = 0.0378). Table 5 demonstrates the results of the uni- and multi-variate analyses for DSS. In the univariate analysis, only the factor “multiple tumors” was significantly correlated with DSS (P = 0.0173). No significant factor was determined by the multivariate analysis.

| Characteristic | n | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| HR (95%CI) | P-value | HR (95%CI) | P-value | ||

| Age | 0.8321 | 0.6843 | |||

| ≤ 69 | 39 | 1 | 1 | ||

| > 69 | 39 | 0.94 (0.50-1.73) | 0.87 (0.45-1.67) | ||

| Gender | 0.2713 | 0.342 | |||

| Female | 17 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Male | 61 | 1.54 (0.73-3.80) | 1.51 (0.68-3.85) | ||

| Occult HBV infection | 0.6039 | 0.5263 | |||

| Absent | 51 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Present | 27 | 1.18 (0.61-2.20) | 1.23 (0.63-2.31) | ||

| Alcohol abuse | 0.3061 | ||||

| Absent | 59 | 1 | |||

| Present | 19 | 1.45 (0.69-2.82) | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.2441 | ||||

| Absent | 51 | 1 | |||

| Present | 27 | 1.45 (0.76-2.67) | |||

| NASH | 0.7366 | ||||

| Absent | 70 | 1 | |||

| Present | 8 | 0.84 (0.25-2.10) | |||

| Obesity | 0.9432 | ||||

| Absent | 54 | 1 | |||

| Present | 24 | 1.02 (0.51-1.93) | |||

| Fibrosis | 0.7084 | ||||

| F0-2 | 44 | 1 | |||

| F3,4 | 34 | 1.12 (0.60-2.06) | |||

| Vp | 0.022 | 0.0378 | |||

| Absent | 47 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Present | 31 | 2.06 (1.11-3.81) | 2.34 (1.05-5.24) | ||

| T12/T34 | 0.0767 | 0.3344 | |||

| T12 | 38 | 1 | 1 | ||

| T34 | 40 | 1.73 (0.94-3.27) | 0.58 (0.20-1.73) | ||

| Solitary/multiple | 0.0334 | 0.0809 | |||

| Solitary | 47 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Multiple | 31 | 1.94 (1.05-3.58) | 2.17 (0.92-5.25) | ||

| Characteristic | n | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| HR (95%CI) | P-value | HR (95%CI) | P-value | ||

| Age | 0.4181 | 0.2941 | |||

| ≤ 69 | 39 | 1 | 1 | ||

| > 69 | 39 | 0.74 (0.34-1.54) | 0.65 (0.27-1.44) | ||

| Gender | 0.3814 | 0.4598 | |||

| Female | 17 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Male | 61 | 1.51 (0.62-4.48) | 1.45 (0.56-4.56) | ||

| Occult HBV infection | 0.4661 | 0.4693 | |||

| Absent | 51 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Present | 27 | 1.32 (0.60-2.78) | 1.33 (0.60-2.88) | ||

| Alcohol abuse | 0.5064 | ||||

| Absent | 59 | 1 | |||

| Present | 19 | 1.34 (0.52-3.02) | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.4775 | ||||

| Absent | 51 | 1 | |||

| Present | 27 | 1.31 (0.60-2.76) | |||

| NASH | 0.6755 | ||||

| Absent | 70 | 1 | |||

| Present | 8 | 1.26 (0.37-3.27) | |||

| Obesity | 0.6466 | ||||

| Absent | 54 | 1 | |||

| Present | 24 | 1.20 (0.53-2.53) | |||

| Fibrosis | 0.1392 | 0.2147 | |||

| F0-2 | 44 | 1 | 1 | ||

| F3,4 | 34 | 1.74 (0.84-3.73) | 1.62 (0.75-3.58) | ||

| Vp | 0.0806 | 0.1478 | |||

| Absent | 47 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Present | 31 | 1.92 (0.91-4.03) | 2.00 (0.78-5.08) | ||

| T12/T34 | 0.0824 | 0.6238 | |||

| T12 | 38 | 1 | 1 | ||

| T34 | 40 | 1.92 (0.92-4.15) | 0.72 (0.19-2.75) | ||

| Solitary/multiple | 0.0173 | 0.0984 | |||

| Solitary | 47 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Multiple | 31 | 2.44 (1.17-5.19) | 2.55 (0.84-7.96) | ||

Many studies have reported an association between OBI and HCC[9]. A meta-analysis in 2012 demonstrated that OBI increases the risk of developing HCC in both HCV- and non-HCV-infected patients[20]. However, other studies did not find such an association[21,22]. Although the debate remains, OBI has been recognized as a possible etiology in the development of HCC. Pathogenetic mechanisms of HCC development via OBI would be implicated in HBV-induced hepatocarcinogenesis, namely chronically sustained inflammation and direct oncogenic effect through integration into the host genome[9,23].

If OBI is an important etiology of HCC, it is quite important to clarify the clinical characteristics and outcomes of OBI-related HCC because different etiologies of HCC may modulate the clinical characteristics and outcomes, thereby requiring different preventive and therapeutic strategies. We therefore focused on NBNC HCC cases which were not influenced by HCV or overt HBV infection.

The prevalence of OBI in this study was 27/78 patients (34.6%). The prevalence of OBI has varied widely among the reported case series[8,24]. The difference in the prevalence of OBI may be due to the lack of methodological uniformity among the different studies[11]. Although the gold standard to diagnose OBI is the detection of HBV DNA in hepatocytes, studies testing OBI by using serum samples have been reported, and the methods of DNA detection varied widely. In addition, the detection of HBc antibody in the serum of HBsAg-negative patients has been used as a surrogate serum marker of OBI[12]. The previous reported prevalence of OBI varied from 12.1% to 78.0% in an anti-HBc positive patient series and from 5.7% to 50.0% in a series in which HBV-DNA was detected in hepatocytes or serum samples[12].

In the present study, OBI was determined by the HBV-DNA amplification of at least two different sets of primers by TaqMan real-time PCR using DNA extracted from FFPE tissues. It has been stated that the DNA extraction from frozen tissues was better than that from FFPE[11]. In addition, all previous OBI studies using liver tissue were based on the frozen or raw liver tissue. Therefore, it was challenging to analyze the OBI status from FFPE samples. We have performed a pilot study using DNA extracted from FFPE tissues of overt HBV infection cases, and the results confirmed good HBV amplification in each primer set. Nevertheless, the possibility cannot be denied that the prevalence of OBI in this study would have been higher if frozen tissues were available. HBV covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) is harbored in the nucleus of HBV-infected hepatocytes, and therefore the results might have been affected if we had examined ccc DNA.

Our comparison of the OBI and non-OBI groups revealed that the patients with OBI were significantly younger than the patients without OBI at the time of surgery. This finding seems to support hepatocarcinogenesis of OBI. Recently, similar result has been reported. Coppola et al[25] analysed OBI in 68 consecutive HBsAg-negative patients with HCC by the presence of HBV DNA in at least two different PCRs and found that patients with OBI were significantly younger than the patients without OBI (mean age: 65.7 vs 71.2, P = 0.03). However, these results involving our series are not conclusive because the infection period of OBI was unknown. Additional studies are thus needed before a conclusion can be made regarding whether NBNC HCC develops more often in younger individuals with OBI compared to non-OBI patients.

The impact of OBI on liver fibrosis remains controversial. Several studies suggest an impact of OBI on the progression of liver fibrosis[25-29], whereas other studies found no association between OBI and liver fibrosis[29-32]. In the present study, we compared the degree of background liver fibrosis between the OBI and non-OBI cases, and we observed that the OBI group had a higher proportion (51.8%) of severe fibrosis cases (F3-4) compared to the non-OBI group (39.2%), although the difference was not significant.

Analyses of the surgical outcomes and clinicopathologic features according to OBI status were the main purpose of this study. Surgical outcomes according to known NBNC HCC etiologies such as alcohol, NAFLD/NASH, diabetes mellitus and obesity had been well investigated[1,33-36]. However, to the best of our knowledge, no previous study investigated the association of OBI status and surgical outcomes in patients with NBNC HCC. Previous studies regarding OBI have been focused on the prevalence, the risk of developing HCC, and the prevalence of OBI in HCC cases[9,37,38].

Our present analyses of surgical outcome (DFS, OS and DSS) revealed that OBI status did not affect the surgical outcomes of NBNC HCC patients. The other analyzed etiologies also did not affect the surgical outcomes. Only tumor-related factors (i.e., portal vein invasion, T-stage and multiple tumor) were associated with surgical outcomes of NBNC HCC. These findings indicate that the surgical outcome of NBNC HCC does not depend on the type of etiologies but that it does depend on the early detection of HCC. Therefore, a periodical screening of HCC using the abdominal echo and/or serum tumor markers is quite important for individuals who have one or more risk factors for NBNC HCC. For the early detection of NBNC HCC, the efficacy of the OBI screening using clinical samples (such as peripheral blood or liver biopsy specimen) should be discussed by accumulation of studies regarding OBI using clinical samples.

The limitations of our study were its retrospective nature, the long study period and the small number of patients. Information of actual number of tumors, viral serological markers except for HBsAg and HCVAb, and status of neoadjuvant treatments were not available. Diagnostic and therapeutic modalities also have changed in the recent decades. Our patients with NBNC HCC showed frequent overlapping in their etiology. Therefore, it is not an ideal method to compare OBI-associated patients to all the other NBNC patients. Association between metabolic factors (diabetes mellitus, NASH, and obesity) and HCC is considered much weaker than that of those of HBV and/or HCV. Therefore, it is doubtful these metabolic factors truly affected development of HCC.

In conclusion, the results of our study indicate that OBI was found in 34.6% of our series of patients with NBNC HCC. The patients with OBI were younger those without OBI at the time of surgery, and the OBI cases were frequently overlapped with other etiologies. The patients’ surgical outcomes were not affected by the OBI status but were affected by only tumor-related factors, and thus the importance of the early detection of the tumors was reconfirmed. We hope to conduct larger retrospective or prospective studies to test our present findings.

Although many epidemiological and virological studies regarding occult HBV infection (OBI) have accumulated, the surgical outcomes of OBI-associated non-B, non-C (NBNC) hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) have not been focused.

OBI was found in 27/78 (34.6%) patients with NBNC HCC. The OBI patients were significantly younger than the non-OBI patients at the time of surgery, and the OBI cases were frequently overlapped with other etiologies. OBI had no impact on surgical outcomes. Only tumor-related factors affected the surgical outcomes.

The results of present study indicated the possibility of OBI screening from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue. The importance of the early detection of HCC by a periodical checkup for individuals who have one or more risk factors for NBNC HCC was reconfirmed.

In this study, OBI was determined by the HBV-DNA amplification of at least two different sets of primers by TaqMan real-time PCR using DNA extracted from FFPE tissues. NBNC-HCC is defined as hepatocellular carcinoma that has arisen in an individual who is negative for both hepatitis B surface antigen and hepatitis C antibody. Disease-free survival (DFS) was determined as the length of time after surgery that the patient survived without new lesions of HCC. Overall survival (OS) was determined from the time of surgery to the time of death or the most recent follow-up. Disease-specific survival (DSS) was determined from the time of surgery to the time of cancer-related death or the most recent follow-up.

It is a very interesting retrospective study in which they were able to show from the formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue DNA of 78 patients that OBI had no impact on the surgical outcome and surgical outcomes of NBNC HCC depend on early tumor detection. This finding indicates that the importance of a periodic medical examination for individuals who have NBNC HCC risk factors. It is well-written, and presented.

We thank Dr. Hidenobu Soejima (Division of Molecular Genetics and Epigenetics, Department of Biomolecular Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Saga University) for his valuable advice about the analysis of the TaqMan real-time PCR.

| 1. | Tateishi R, Okanoue T, Fujiwara N, Okita K, Kiyosawa K, Omata M, Kumada H, Hayashi N, Koike K. Clinical characteristics, treatment, and prognosis of non-B, non-C hepatocellular carcinoma: a large retrospective multicenter cohort study. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:350-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Seeff LB, Hoofnagle JH. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in areas of low hepatitis B and hepatitis C endemicity. Oncogene. 2006;25:3771-3777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Marrero JA, Fontana RJ, Su GL, Conjeevaram HS, Emick DM, Lok AS. NAFLD may be a common underlying liver disease in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Hepatology. 2002;36:1349-1354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 284] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | Streba LA, Vere CC, Rogoveanu I, Streba CT. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, metabolic risk factors, and hepatocellular carcinoma: an open question. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:4103-4110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Haddow JE, Palomaki GE, McClain M, Craig W. Hereditary haemochromatosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in males: a strategy for estimating the potential for primary prevention. J Med Screen. 2003;10:11-13. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Moucari R, Rautou PE, Cazals-Hatem D, Geara A, Bureau C, Consigny Y, Francoz C, Denninger MH, Vilgrain V, Belghiti J. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Budd-Chiari syndrome: characteristics and risk factors. Gut. 2008;57:828-835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Suzuki Y, Ohtake T, Nishiguchi S, Hashimoto E, Aoyagi Y, Onji M, Kohgo Y; Japan Non-B, Non-C Liver Cirrhosis Study Group. Survey of non-B, non-C liver cirrhosis in Japan. Hepatol Res. 2013;43:1020-1031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Raimondo G, Caccamo G, Filomia R, Pollicino T. Occult HBV infection. Semin Immunopathol. 2013;35:39-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pollicino T, Saitta C. Occult hepatitis B virus and hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:5951-5961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | European Association For The Study Of The Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: Management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2012;57:167-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2323] [Cited by in RCA: 2411] [Article Influence: 172.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Raimondo G, Allain JP, Brunetto MR, Buendia MA, Chen DS, Colombo M, Craxì A, Donato F, Ferrari C, Gaeta GB. Statements from the Taormina expert meeting on occult hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2008;49:652-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 598] [Cited by in RCA: 618] [Article Influence: 34.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Coppola N, Onorato L, Pisaturo M, Macera M, Sagnelli C, Martini S, Sagnelli E. Role of occult hepatitis B virus infection in chronic hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:11931-11940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Said ZN. An overview of occult hepatitis B virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1927-1938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 14. | Ocana S, Casas ML, Buhigas I, Lledo JL. Diagnostic strategy for occult hepatitis B virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1553-1557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhang ZH, Wu CC, Chen XW, Li X, Li J, Lu MJ. Genetic variation of hepatitis B virus and its significance for pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:126-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 16. | Zhu HL, Li X, Li J, Zhang ZH. Genetic variation of occult hepatitis B virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:3531-3546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kai K, Koga H, Aishima S, Kawaguchi A, Yamaji K, Ide T, Ueda J, Noshiro H. Impact of smoking habit on surgical outcomes in non-B non-C patients with curative resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:1397-1405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Kondo R, Nakashima O, Sata M, Imazeki F, Yokosuka O, Tanikawa K, Kage M, Yano H; Liver Cancer Study Group of Kyushu. Pathological characteristics of patients who develop hepatocellular carcinoma with negative results of both serous hepatitis B surface antigen and hepatitis C virus antibody. Hepatol Res. 2014;44:1039-1046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ichida F, Tsuji T, Omata M, Ichida T, Inoue K, Kamimura T, Yamada G, Hino K, Yokosuka G, Suzuki H. New Inuyama classification; new criteria for histological assessment of chronic hepatitis. Int Hepatol Commun. 1996;6:112-119. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 253] [Cited by in RCA: 278] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Shi Y, Wu YH, Wu W, Zhang WJ, Yang J, Chen Z. Association between occult hepatitis B infection and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Liver Int. 2012;32:231-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lok AS, Everhart JE, Di Bisceglie AM, Kim HY, Hussain M, Morgan TR; HALT-C Trial Group. Occult and previous hepatitis B virus infection are not associated with hepatocellular carcinoma in United States patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2011;54:434-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kusakabe A, Tanaka Y, Orito E, Sugauchi F, Kurbanov F, Sakamoto T, Shinkai N, Hirashima N, Hasegawa I, Ohno T. A weak association between occult HBV infection and non-B non-C hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:298-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Arzumanyan A, Reis HM, Feitelson MA. Pathogenic mechanisms in HBV- and HCV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:123-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 581] [Cited by in RCA: 642] [Article Influence: 49.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Torbenson M, Thomas DL. Occult hepatitis B. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:479-486. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Coppola N, Onorato L, Iodice V, Starace M, Minichini C, Farella N, Liorre G, Filippini P, Sagnelli E, de Stefano G. Occult HBV infection in HCC and cirrhotic tissue of HBsAg-negative patients: a virological and clinical study. Oncotarget. 2016;7:62706-62714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Cacciola I, Pollicino T, Squadrito G, Cerenzia G, Orlando ME, Raimondo G. Occult hepatitis B virus infection in patients with chronic hepatitis C liver disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:22-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 491] [Cited by in RCA: 478] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Mrani S, Chemin I, Menouar K, Guillaud O, Pradat P, Borghi G, Trabaud MA, Chevallier P, Chevallier M, Zoulim F. Occult HBV infection may represent a major risk factor of non-response to antiviral therapy of chronic hepatitis C. J Med Virol. 2007;79:1075-1081. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Matsuoka S, Nirei K, Tamura A, Nakamura H, Matsumura H, Oshiro S, Arakawa Y, Yamagami H, Tanaka N, Moriyama M. Influence of occult hepatitis B virus coinfection on the incidence of fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis C. Intervirology. 2008;51:352-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Squadrito G, Cacciola I, Alibrandi A, Pollicino T, Raimondo G. Impact of occult hepatitis B virus infection on the outcome of chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2013;59:696-700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Sagnelli E, Imparato M, Coppola N, Pisapia R, Sagnelli C, Messina V, Piai G, Stanzione M, Bruno M, Moggio G. Diagnosis and clinical impact of occult hepatitis B infection in patients with biopsy proven chronic hepatitis C: a multicenter study. J Med Virol. 2008;80:1547-1553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Fukuda R, Ishimura N, Niigaki M, Hamamoto S, Satoh S, Tanaka S, Kushiyama Y, Uchida Y, Ihihara S, Akagi S. Serologically silent hepatitis B virus coinfection in patients with hepatitis C virus-associated chronic liver disease: clinical and virological significance. J Med Virol. 1999;58:201-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Torbenson M, Kannangai R, Astemborski J, Strathdee SA, Vlahov D, Thomas DL. High prevalence of occult hepatitis B in Baltimore injection drug users. Hepatology. 2004;39:51-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Wakai T, Shirai Y, Sakata J, Korita PV, Ajioka Y, Hatakeyama K. Surgical outcomes for hepatocellular carcinoma in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:1450-1458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Reddy SK, Steel JL, Chen HW, DeMateo DJ, Cardinal J, Behari J, Humar A, Marsh JW, Geller DA, Tsung A. Outcomes of curative treatment for hepatocellular cancer in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis versus hepatitis C and alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2012;55:1809-1819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Kudo A, Tanaka S, Ban D, Matsumura S, Irie T, Ochiai T, Nakamura N, Arii S, Tanabe M. Alcohol consumption and recurrence of non-B or non-C hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy: a propensity score analysis. J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:1352-1361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Nishikawa H, Arimoto A, Wakasa T, Kita R, Kimura T, Osaki Y. Comparison of clinical characteristics and survival after surgery in patients with non-B and non-C hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatitis virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer. 2013;4:502-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Chen L, Zhao H, Yang X, Gao JY, Cheng J. HBsAg-negative hepatitis B virus infection and hepatocellular carcinoma. Discov Med. 2014;18:189-193. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Huang X, Hollinger FB. Occult hepatitis B virus infection and hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review. J Viral Hepat. 2014;21:153-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Balaban YH, Bock CT, Namisaki T, Sazci A S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ