Published online Feb 27, 2026. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v18.i2.114206

Revised: October 5, 2025

Accepted: December 12, 2025

Published online: February 27, 2026

Processing time: 152 Days and 3.1 Hours

Fatigue is common and debilitating in primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) without clear relation to disease stage; mechanisms remain unclear. Circadian disruption is reported in end-stage liver disease, but evidence in non-cirrhotic PBC, and links to fatigue, is scarce.

To investigate the severity and phenotype of fatigue, daytime sleepiness, and chronotype in non-cirrhotic PBC, and compare findings with matched healthy controls (HC) and non-cirrhotic primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC).

Participants completed the Fatigue Impact Scale, Epworth Sleepiness Scale, and Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire Self-Assessment. Demographics, sleep habits, employment, and fatigue subtype (mental vs muscular) were recorded. In PBC/PSC, PBC-40 fatigue/itch domains and disease characteristics were an

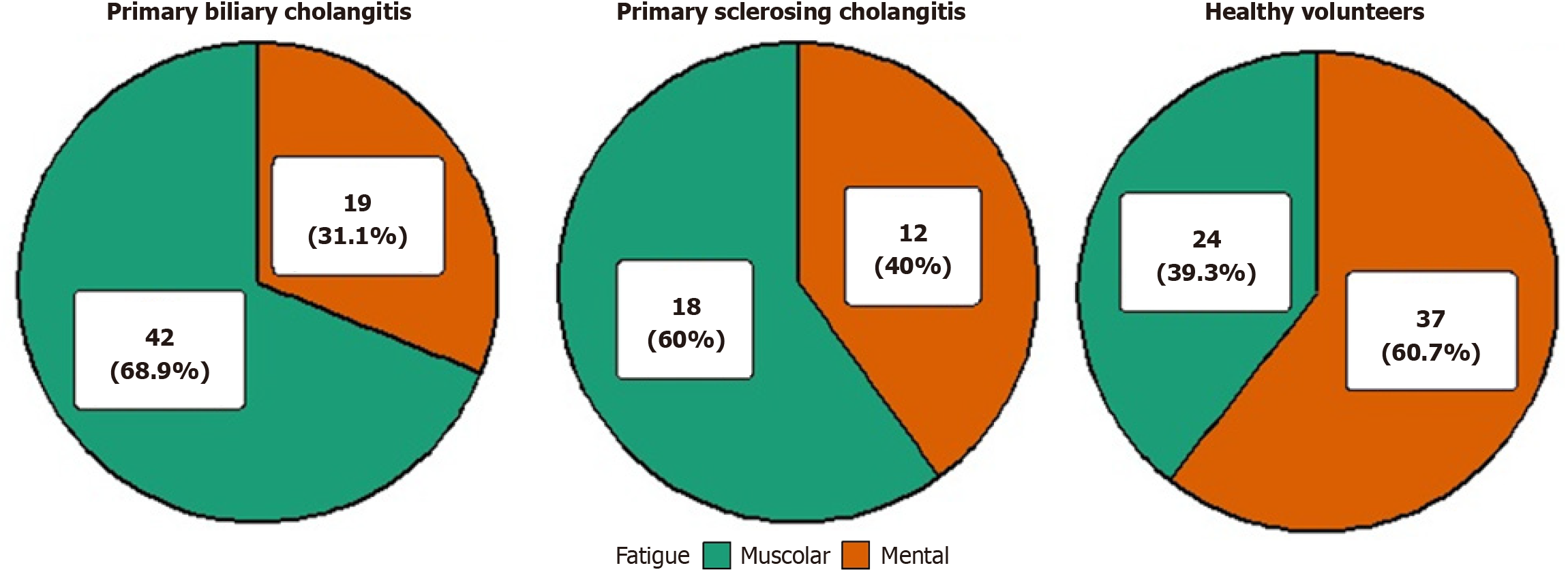

We enrolled 152 individuals: 61 PBC, 30 PSC, and 61 HC. Global fatigue scores did not differ across groups. Muscular fatigue predominated in PBC/PSC, whereas HC more often reported mental fatigue; this pattern persisted after stratifying by employment and sex. In adjusted analyses, HC had lower odds of muscular fatigue than PBC [odd ratio (OR) = 0.30, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.14-0.63; P = 0.002]; PSC did not differ from PBC (OR = 1.25, 95%CI: 0.44-3.71; P = 0.681). Older age independently increased the odds of muscular fatigue (OR = 1.04 per year, 95%CI: 1.01-1.07; P = 0.016). Daytime sleepiness was low and similar between groups. Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire Self-Assessment scores clustered in the intermediate range; age, not disease, predicted greater morningness.

In non-cirrhotic PBC, fatigue shows a predominantly muscular phenotype independent of demograph

Core Tip: In non-cirrhotic primary biliary cholangitis, fatigue burden is similar to healthy controls and primary sclerosing cholangitis, but its phenotype is predominantly muscular (approximately 69%), independent of sex, age-adjusted employment, or routine disease metrics; daytime sleepiness and sleep duration are low/normal, and chronotype clusters in the intermediate range, with age - not disease - driving greater morningness. Primary sclerosing cholangitis shows a similar (weaker) direction of effect. These findings support routine fatigue phenotyping and muscle-focused interventions over cholestasis-directed therapies, and argue for objective endpoints (e.g., 31phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy, actigraphy) in future trials.

- Citation: Curto A, Tanturli M, Iamello RG, Rossi P, Mengozzi G, Dei L, Mello T, Innocenti T, Dragoni G, Galli A, Lynch EN. Fatigue and circadian rhythm in non-cirrhotic primary biliary cholangitis: An exploratory comparison with primary sclerosing cholangitis and healthy controls. World J Hepatol 2026; 18(2): 114206

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v18/i2/114206.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v18.i2.114206

Fatigue represents one of the most prevalent and debilitating symptoms in patients with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), affecting approximately 50% of individuals and presenting at a severe level in up to 20% of cases[1,2]. Notably, this symptom may manifest early in the disease course and, in contrast to other hallmark features of PBC such as pruritus, shows no clear association with biochemical markers of cholestasis or histological disease stage[1-3]. Instead, fatigue severity correlates with demographic factors, particularly sex and age at disease onset, with younger women being disproportionately affected[3].

Although ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) remains the cornerstone of PBC therapy, improving cholestatic liver biochemistry and enhancing transplant-free survival, it has not demonstrated any significant impact on fatigue, which frequently persists even after liver transplantation[4]. Importantly, the severity of fatigue has emerged as an independent predictor of both liver-related mortality and post-transplant clinical outcomes[5].

The pathophysiological mechanisms underlying fatigue in PBC remain incompletely understood. Current evidence indicates that it arises from both peripheral and central mechanisms, which interact to produce overwhelming tiredness and reduced physical and mental endurance[6]. In the United Kingdom-PBC research cohort between 2008 and 2011, cognitive symptoms were reported to be common, with 36% of patients experiencing at least moderate cognitive im

Data regarding fatigue in primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) are limited and somewhat conflicting; while earlier series suggested low symptom burden, more recent cohorts report substantial prevalence and links with autonomic dysfunction, though underlying mechanisms remain obscure[9-12]. Fatigue is a highly common subjective symptom even in the general population, where it can occur in the absence of diagnosed diseases and serve as an early indicator of health issues[13]. According to a recent meta-analysis involving over 600000 healthy individuals, the global prevalence of general fatigue (i.e., non-chronic) is 24.2%, while chronic fatigue (lasting more than six months) affects 7.7% of the population. Among adults, the prevalence is 20.4% for general fatigue and 10.1% for chronic fatigue. In approximately three out of four cases, fatigue is classified as “unexplained”, meaning it cannot be attributed to any known medical condition[14]. This highlights how chronic tiredness is often underestimated, despite its potential impact on quality of life and its role as a precursor to future clinical conditions[15]. Moreover, fatigue frequently co-occurs with other somatic or psychological symptoms such as pain and depression[16], and it is more common in women, with a global odds ratio (OR) of 1.4 compared to men[17].

Circadian rhythms are endogenous, approximately 24-hour cycles governing physiological and psychological functions at levels from cellular processes to behavior[18-21]. In humans, the sleep-wake cycle is the most evident rhythm, entrained by light-dark cues via the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN). SCN neurons display circadian oscillations in electrical firing, intracellular Ca2+ and clockgene expression[22], acting as the central pacemaker. Peripheral clocks in nearly all tissues generate autonomous rhythms, which the SCN synchronizes through endocrine, neural, and metabolic signals[21,23].

Disruption of circadian timing contributes to fatigue and predisposes to metabolic disorders (e.g., diabetes, obesity)[24], cancer[25], neurodegeneration[26], and cardiovascular disease[27]. Individual chronotypes, morning types, evening types and neither type, reflect genetic and environmental determinants of circadian phase[28]. Misalignment between internal rhythms and external demands (e.g., shift work, jet lag) exacerbates sleep debt and daytime fatigue. Data on chronotype in PBC remain scarce: The only dedicated study, conducted over a decade ago in Padua, reported delayed sleep timing and an evening chronotype preference in a small PBC cohort, changes that were linked to poorer sleep quality and quality of life[29]. By contrast, multiple studies in cirrhosis consistently demonstrate pronounced circadian disruption[30].

The aim of this study was to assess the prevalence and severity of fatigue and daytime sleepiness, as well as the integrity of sleep-wake rhythms, in a well-characterized cohort of non-cirrhotic patients with PBC. We also investigated how disease-related variables, treatment exposures, and environmental factors modulate these parameters. To gauge the specificity of our findings, we compared results with those from a matched cohort of healthy volunteers and a cohort of patients with PSC.

This was an exploratory retrospective, cross-sectional observational study conducted at the Hepatology Outpatient Clinic of Careggi University Hospital, Florence (Italy), between April 2024 and April 2025. Non-cirrhotic PBC patients and a control group of PSC patients were recruited from the same clinic. A second control group comprised healthy, non-shift-working hospital staff who underwent a standard screening procedure and were matched by age and sex to the PBC cohort.

For PBC and PSC patients, inclusion criteria were age > 18 years, confirmed diagnosis of PSC and PBC according to current European guidelines[1,31], absence of cirrhosis on imaging and elastography, absence of hepatocellular carcinoma, sufficient language proficiency to complete questionnaires and capability to give informed consent. Exclusion criteria were: Presence of comorbidities with potential impact on fatigue and circadian rhythm such as active psychiatric disorders, anemia, end-stage kidney disease, uncontrolled thyroid disease and cardiopathy, active treatments which could alter chronotype and increase fatigue such as hypnotic-sedative treatment, beta-blockers, anti-histaminic drugs and opioids, active smoking of 20 (or more) cigarettes per day, active use of over 20 g of alcohol on a daily basis for women and 30 g for men, and any use of illicit drugs. For HC, inclusion criteria were age > 18 years, sufficient language pro

All participants [PBC, PSC and healthy controls (HC)] completed the following questionnaires: Fatigue Impact Scale (FIS); Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), and Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire Self-Assessment (MEQ-SA). PBC and PSC patients also completed the itch and fatigue domains of the PBC-40. Participants were asked to classify their fatigue as predominantly “mental”, defined as “lack of intention” or “muscular”, defined as “lack of ability”. Sociodemographic data, work status, and self-reported sleep habits were recorded. For PBC and PSC patients, medical data including therapy regimens, total blood count, liver enzymes, liver function tests, estimated glomerular filtrate rate, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), and FibroScan® scores were retrieved from medical records. FibroScan® measurements were interpreted according to the cut-offs proposed by Castera et al[32], F0-F1 ≤ 7 kPa, F2 ≤ 9.5 kPa and F3 ≤ 12.5 kPa. PSC and PBC patients’ medical data were reassessed in order to exclude cirrhosis.

Descriptive statistics summarized demographic and clinical features. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD when approximately normally distributed and as median (interquartile range) otherwise. Normality was evaluated by Shapiro-Wilk test and inspection of histograms and Q-Q plots. Categorical variables were presented as n (%). For any multiple pairwise comparisons, P-values were adjusted using Holm’s method. No global correction was applied across outcome families or model coefficients; results are exploratory and presented with effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Group comparisons were performed using χ2 or Fisher exact test, Student’s t test, Mann Whitney, ANOVA, and Kruskal-Wallis tests as appropriate. In case of multiple comparison, Holm method was applied to adjust the P values. Multivariate generalized linear model regression models were assessed predictors of fatigue type and chronotype, controlling for age, sex, employment status, and working hour. The variables included in the generalized linear model models were chosen based on univariate analysis and clinical relevance. The Akaike information criterion method was also applied to select the most informative covariates. The variance inflation factor was calculated in order to assess multicollinearity. A focused analysis was conducted on the employed and female subset to control for occupational and sex influences on fatigue and circadian rhythm. Two-sided P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Given the exploratory design of the study, no a priori sample size calculation was conducted. A post hoc analysis, evaluating differences in MEQ-SA among the three patient groups using the ANOVA test, indicated that 80% statistical power was achieved. Similarly, 80% power was attained when comparing the proportions of muscular and mental fatigue in CBP patient’s vs healthy subjects. The lower number of participants in the CSP group decreased the overall power for the CBP vs CSP comparison. Power calculations were performed using GPower version 3.1.9.6. (Supp

A total of 152 participants were included in the study, 61 with non-cirrhotic PBC, 30 with non-cirrhotic PSC and 61 HC - as summarized in Table 1. Overall, the three groups differed in age, body mass index (BMI), number of working days per week, hours worked per day, chronotype as assessed by the MEQ-SA, sex distribution, employment rate, and fatigue subtype.

| Overall (n = 152) | PBC (n = 61) | PSC (n = 30) | HC (n = 61) | P value | |

| Age, years | 61.50 (54.00-68.00) | 63.00 (57.00-73.00) | 50.50 (30.00-57.75) | 62.00 (57.00-71.00) | < 0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.67 (20.88-26.31) | 24.58 (22.39-27.34) | 22.56 (20.45-24.87) | 23.18 (20.48-25.30) | 0.012 |

| Sleep duration hours | 7.00 (6.00-7.12) | 6.50 (5.50-7.00) | 7.00 (6.50-7.50) | 6.50 (6.00-7.00) | 0.130 |

| Number of awakenings | 1.50 (1.50-1.50) | 1.50 (1.50-1.50) | 1.50 (0.00-2.25) | 1.50 (1.50-1.50) | 0.564 |

| Working days/week | 5.00 (0.00-5.00) | 5.00 (0.00-5.00) | 5.00 (5.00-6.00) | 5.00 (0.00-5.00) | 0.030 |

| Working hours/day | 5.50 (0.00-8.00) | 5.00 (0.00-8.00) | 7.00 (4.00-8.00) | 4.00 (0.00-8.00) | 0.040 |

| Disease duration, years | 10.00 (4.00-16.00) | 10.50 (4.00-16.00) | 10.00 (4.00-16.00) | N/A | 0.914 |

| Sex | < 0.001 | ||||

| Female | 121 (79.6) | 54 (88.5) | 13 (43.3) | 54 (88.5) | |

| Male | 31 (20.4) | 7 (11.5) | 17 (56.7) | 7 (11.5) | |

| Nocturnal light exposure | 0.676 | ||||

| No | 140 (92.1) | 55 (90.2) | 29 (96.7) | 56 (91.8) | |

| Yes | 12 (7.9) | 6 (9.8) | 1 (3.3) | 5 (8.2) | |

| Employment | 0.011 | ||||

| Employed | 85 (55.9) | 29 (47.5) | 19 (63.3) | 37 (60.7) | |

| Retired | 55 (36.2) | 28 (45.9) | 5 (16.7) | 22 (36.1) | |

| Unemployed | 12 (7.9) | 4 (6.6) | 6 (20.0) | 2 (3.3) | |

| Anti-mitochondrial antibodies | 1.000 | ||||

| Negative | 11 (18.0) | 11 (18.0) | N/A | N/A | |

| Positive | 50 (82.0) | 50 (82.0) | N/A | N/A | |

| Anti-Sp100 | 1.000 | ||||

| Negative | 48 (78.7) | 48 (78.7) | N/A | N/A | |

| Positive | 13 (21.3) | 13 (21.3) | N/A | N/A | |

| Fibroscan | 0.362 | ||||

| F1 | 68 (75.6) | 45 (73.8) | 23 (79.3) | N/A | |

| F2 | 16 (17.8) | 13 (21.3) | 3 (10.3) | N/A | |

| F3 | 6 (6.7) | 3 (4.9) | 3 (10.3) | N/A | |

| Drug | 1.000 | ||||

| Fibrates | 15 (24.6) | 15 (24.6) | N/A | N/A | |

| Obeticholic acid | 8 (13.1) | 8 (13.1) | N/A | N/A | |

| Ursodeoxycholic acid | 38 (62.3) | 38 (62.3) | N/A | N/A |

In details the PBC cohort was largely female (88.5%) with a median age of 63 years (57-73 years) and a median BMI of 24.6 kg/m2 (22.4-27.3). Nearly half of these patients were employed (47.5%), whereas 6.6% were unemployed and 45.9% retired; among those working, the typical commitment was five working days per week for about five hours per day (0-5 days; 0-8 hours). Median disease duration was 10.5 years (4-16 years), and liver stiffness assessed by transient el

The HC group was deliberately matched to the PBC cohort. Only BMI differed statistically between the two groups, but the absolute difference was small and unlikely to be clinically meaningful [median of 23.2 kg/m2 (20.5-25.3 kg/m2); P = 0.012; Supplementary Table 5]. In contrast, PSC patients reflected the distinctive epidemiology of that disease: They were younger [median of 50.5 years, (30.0-57.8 years)] and predominantly male (56.7%; both P < 0.001), with a lower median BMI of 22.6 kg/m2 (20.5-24.9 kg/m2; P = 0.012). A greater proportion were employed than in PBC (63.3% vs 47.5%; P = 0.01; Supplementary Table 6).

In PBC, median hemoglobin was 13.1 g/dL (12.3-13.8 g/dL) and platelet count 256 × 103 U/μL (222-290 U/μL). TSH and renal function were within reference limits [median 1.23 μU/mL (1.11-2.04 μU/mL) and 82 mL/minute (70.0-90.0 mL/minute), respectively]. Liver enzymes were mildly elevated or normal; bilirubin, albumin and international normalized ratio were preserved. AMA were detected in 73.8% and anti-Sp100 in 21.3% of patients. Compared with PBC, PSC patients differed in hemoglobin, estimated glomerular filtrate rate, TSH, and total bilirubin; although these inter-group differences reached statistical significance, they were not clinically meaningful. Full biochemistry profiles for both cohorts are presented in Table 2.

| Overall (n = 152) | PBC (n = 61) | PSC (n = 30) | HC (n = 61) | P value | |

| eGFR, mL/minU/1.73 m2 | 90.00 (78.35-90.00) | 82.00 (70.00-90.00) | 90.00 (90.00-90.00) | N/A | < 0.001 |

| Thyroid stimulating hormone, mIU/L | 2.01 (1.13-2.74) | 1.23 (1.11-2.04) | 2.85 (2.50-3.00) | N/A | < 0.001 |

| Haemoglobin, g/dL | 13.30 (12.50-14.10) | 13.10 (12.30-13.80) | 13.80 (13.00-15.20) | N/A | 0.007 |

| Hematocrit, % | 41.10 (38.92-42.98) | 41.10 (39.10-42.50) | 41.50 (38.10-45.00) | N/A | 0.360 |

| Platelets, 109/L | 258.00 (212.25-300.75) | 256.00 (222.00-290.00) | 267.00 (202.00-312.00) | N/A | 0.772 |

| Ig(immunoglobulin), mg/dL | 189.00 (148.00-303.50) | 206.00 (155.50-304.25) | 156.00 (105.50-269.50) | N/A | 0.083 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 4.08 (3.90-4.31) | 4.00 (3.80-4.30) | 4.10 (4.00-4.50) | N/A | 0.110 |

| INR | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | N/A | 0.277 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.63 (0.50-0.80) | 0.60 (0.50-0.71) | 0.85 (0.52-1.22) | N/A | 0.008 |

| ALT, U/L | 23.00 (17.00-39.00) | 22.00 (17.00-36.00) | 27.50 (19.00-48.75) | N/A | 0.157 |

| AST, U/L | 27.00 (21.00-33.00) | 25.00 (21.00-33.00) | 29.00 (22.25-41.75) | N/A | 0.179 |

| ALP, U/L | 105.00 (79.00-138.00) | 105.00 (77.00-138.00) | 104.50 (84.75-140.50) | N/A | 0.482 |

| GGT, U/L | 65.00 (32.00-118.00) | 54.00 (33.00-86.00) | 75.50 (30.50-154.25) | N/A | 0.167 |

Night-time sleep duration was comparable in PBC and HC (both median 6.5 hours, IQR 5.5-7.0 and 6.0-7.0, respectively) and marginally longer in PSC [7.0 hours, (6.5-7.5 hours); P = 0.08; Supplementary Table 5]. The median number of nocturnal awakenings was 1.5 (1.5-1.5) in PBC and HC and 1.5 (0-2.25) in PSC. Daytime somnolence was low across cohorts [ESS medians: 6 (3.0-9.0) in PBC, 5 (3.0-8.0) in HC, 6 (4.0-9.0) in PSC; P = 0.376], as illustrated in Table 3. Only 7.9% in the entire cohort slept with a bedroom light source with no difference of prevalence amongst the three groups (P = 0.676), as included in Table 1.

| Overall (n = 152) | PBC (n = 61) | PSC (n = 30) | HC (n = 61) | P value | |

| Daytime sleepiness (ESS) | 5.50 (3.75-8.00) | 6.00 (3.00-9.00) | 6.00 (4.00-9.00) | 5.00 (3.00-8.00) | 0.376 |

| Global fatigue (FIS) | 34.00 (16.00-65.50) | 32.00 (16.00-100.00) | 24.00 (6.50-61.25) | 37.00 (21.00-56.00) | 0.308 |

| PBC-40 fatigue domain1 | 22.00 (14.00-30.50) | 18.00 (13.00-30.00) | 25.00 (15.25-30.75) | N/A | 0.1312 |

| Chronotype (MEQ-SA) | 58.00 (53.00-64.00) | 60.00 (55.00-63.00) | 54.50 (46.75-59.00) | 58.00 (53.00-65.00) | 0.018 |

Global fatigue burden, assessed by the FIS, did not differ significantly among groups [medians: 32 (16-100) in PBC, 37 (21-56) in HC, 24 (6.5-6.25) in PSC; P = 0.308], as included in Table 3. Within the PBC-40, the fatigue domain scored 18 (13-30) in PBC and 25 (15.25-30.75) in PSC (P = 0.131). The qualitative pattern of fatigue diverged markedly (Figure 1): Muscular fatigue predominated in cholestatic disease (68.9% in PBC, 60.0% in PSC) whereas mental fatigue was more common in HC (60.7%). The difference vs HC was statistically significant only for PBC (P = 0.002); the PSC-HC comparison did not reach significance (P = 0.076). This distribution was unchanged after stratification by employment status and sex (Supplementary Tables 7 and 8).

In a logistic regression with muscular (vs mental) fatigue as the outcome, HC had substantially lower odds of muscular fatigue than PBC (OR = 0.30, 95%CI: 0.14-0.63; P = 0.002), whereas PSC did not statistically differ from PBC but the OR increases compared to univariate analysis (OR = 0.68, 95%CI: 0.27-1.70 vs OR = 1.25, 95%CI: 0.44-3.71; P = 0.681) indicating that age is associated with the feeling of fatigue. Age independently increased the odds of muscular fatigue (OR = 1.04 per year, 95%CI: 1.01-1.07; P = 0.016), while sex, employment status, and workload (days/week and hours/day) were not associated (Table 4).

| Dependent: Type of fatigue | Mental | Muscular | OR, 95%CI (univariable) | OR, 95%CI (multivariable full) | OR, 95%CI (multivariable) |

| Group | |||||

| PBC | 19 (27.9) | 42 (50.0) | |||

| PSC | 12 (17.6) | 18 (21.4) | 0.68 (0.27-1.70), P = 0.403 | 1.19 (0.39-3.81), P = 0.769 | 1.25 (0.44-3.71), P = 0.681 |

| HC | 37 (54.4) | 24 (28.6) | 0.29 (0.14-0.61), P = 0.001 | 0.29 (0.13-0.63), P = 0.002 | 0.30 (0.14-0.63), P = 0.002 |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 55 (80.9) | 66 (78.6) | |||

| Male | 13 (19.1) | 18 (21.4) | 1.15 (0.52-2.61), P = 0.725 | 1.17 (0.45-3.13), P = 0.753 | |

| Age | 57.1 ± 15.2 | 61.7 ± 12.8 | 1.02 (1.00-1.05), P = 0.047 | 1.04 (1.00-1.08), P = 0.054 | 1.04 (1.01-1.07), P = 0.016 |

| Working hours | 4.8 ± 3.5 | 4.3 ± 3.7 | 0.96 (0.88-1.05), P = 0.425 | 0.98 (0.84-1.16), P = 0.812 | |

| Employment | |||||

| Employed | 42 (61.8) | 43 (51.2) | |||

| Retired | 20 (29.4) | 35 (41.7) | 1.71 (0.86-3.46), P = 0.130 | 0.86 (0.22-3.39), P = 0.821 | |

| Unemployed | 6 (8.8) | 6 (7.1) | 0.98 (0.28-3.36), P = 0.970 | 0.84 (0.20-3.65), P = 0.808 |

The PBC-40 pruritus domain yielded low, nearly identical scores in PBC and PSC (median 3, interquartile range 0-5 and 0.75-5, respectively; P = 0.969), indicating minimal itch in this non-cirrhotic cohort.

MEQ-SA scores clustered in the intermediate range [median 60 (55.0-63.0)] in PBC, 58 (53.0-65.0) in HC, 54.5 (46.75-59.0) in PSC; P = 0.018), although this inter-group difference was statistically significant, driven by lower scores in PSC vs PBC/HC (Supplementary Tables 5, 6, and 9), it did not indicate a systematic shift toward either a morning or an evening chronotype. In a linear regression with MEQ-SA score as the dependent variable, age emerged as the only independent predictor, higher age corresponded to greater morningness, whereas disease group (PSC or HC vs PBC), sex, and occupational variables showed no independent associations (Table 5).

| Chronotype (MEQ-SA) | Value | Coefficient (univariable) | Coefficient (multivariable full) | Coefficient (multivariable) | |

| Group | PBC | 59.3 ± 6.7 | |||

| PSC | 53.8 ± 8.7 | -5.46 (-8.90 to -2.02), P = 0.002 | -2.29 (-6.25 to 1.66), P = 0.253 | -2.38 (-6.07 to 1.30), P = 0.203 | |

| HC | 58.2 ± 8.4 | -1.05 (-3.84 to 1.74), P = 0.459 | -0.76 (-3.51 to 1.99), P = 0.586 | -0.52 (-3.20 to 2.16), P = 0.703 | |

| Sex | Female | 58.3 ± 7.7 | |||

| Male | 55.7 ± 9.1 | -2.58 (-5.75 to 0.59), P = 0.110 | 0.21 (-3.19 to 3.61), P = 0.903 | ||

| Age | 20.0-85.0 | 57.8 ± 8.0 | 0.20 (0.11-0.28), P < 0.001 | 0.20 (0.07-0.32), P = 0.002 | 0.22 (0.11-0.33), P < 0.001 |

| Working hours | 0.0-12.0 | 57.8 ± 8.0 | -0.00 (-0.36 to 0.36), P = 0.997 | 0.33 (-0.22 to 0.89), P = 0.238 | 0.43 (0.06-0.80), P = 0.024 |

| Employment | Employed | 57.9 ± 7.3 | |||

| Retired | 59.1 ± 7.5 | 1.20 (-1.46 to 3.86), P = 0.375 | -0.36 (-5.07 to 4.34), P = 0.879 | ||

| Unemployed | 50.8 ± 11.4 | -7.14 (-11.88 to -2.41), P = 0.003 | -4.03 (-9.11 to 1.06), P = 0.120 | ||

In this study, we analytically characterized fatigue profile, daytime somnolence and circadian preference in a rigorously phenotype cohort of non-cirrhotic PBC patients and compared the findings with both PSC and healthy matched controls. Although global fatigue scores did not differ across the three cohorts, the qualitative pattern of fatigue diverged strikingly: Nearly two-thirds of PBC and PSC patients reported a dominantly muscular phenotype, whereas healthy individuals more frequently described mental fatigue.

On multivariable logistic regression (muscular vs mental fatigue as the outcome), HC had substantially lower odds of muscular fatigue than PBC (OR = 0.30, 95%CI: 0.14-0.63; P = 0.002), whereas PSC did not differ from PBC (OR = 1.25, 95%CI: 0.44-3.71; P = 0.681); age independently increased the odds of muscular fatigue (OR = 1.04 per year, 95%CI: 1.01-1.07; P = 0.016), while sex, employment status, and workload (days/hours) were not associated. These data indicate that the enrichment of muscular fatigue in cholestatic disease, particularly vs HC, is not explained by demographic or occupational factors.

The finding coheres with 31phosphorus-magnetic resonance spectroscopy data demonstrating premature transition to anaerobic metabolism, delayed phosphocreatine recovery and intramuscular acidosis in PBC patients during comparable workloads[8]. Together, these results reinforce the concept that peripheral mechanisms, likely rooted in mitochondrial dysfunction, play a central role even before advanced fibrosis develops. Of note, the prevalence of muscular fatigue in PSC, a condition historically regarded as “fatigue-sparing”[17], aligns with contemporary reports using the experience-sampling method[18] and autonomic testing[19], suggesting that muscle-centered mechanisms may be shared across autoimmune cholangiopathies, albeit with a weaker statistical signal in our cohort, possibly owing to the low numerosity of PSC patients. In keeping with earlier PBC series[1-3], we observed no relationship between fatigue scores and routine liver biochemistry, fibrosis stage, or current treatment with UDCA, fibrates, or obeticholic acid. Patients receiving UDCA for more than a decade were just as likely to experience high muscular fatigue as treatment-naïve individuals, un

Contrary to data in decompensated cirrhosis, where delayed melatonin phase and evening chronotype predominate[39], we found MEQ-SA scores clustered in the intermediate range in all groups, with a modest inter-group difference (overall P = 0.018). However, in multivariable linear regression with MEQ-SA as the dependent variable, age was the only independent predictor, higher age corresponding to greater morningness, while disease group (PSC or HC vs PBC), sex, and occupational variables showed no association. Thus, the small between-group variation in chronotype appears to reflect age structure rather than disease status and did not indicate a systematic shift toward morningness or eveningness chronotype.

Our results also diverge from the study that described an evening preference in 19 PBC patients[38]. Several factors may explain the discrepancy: (1) Our cohort was larger and strictly limited to non-cirrhotic disease; (2) Contemporary light-emitting diode-light exposure patterns and screen use may have altered baseline chronotype distribution in the general population over the past decade; and (3) An adequately matched healthy control group revealed that inter

Our findings highlight muscular fatigue as an under-recognized yet pervasive problem in early cholestatic disease. Routine clinical assessment should therefore differentiate muscular from mental fatigue, as the two may respond to distinct interventions (e.g., graded muscle-energy training vs cognitive pacing). Given minimal pruritus scores in this non-cirrhotic cohort and low daytime sleepiness, anti-itch therapies and hypnotics are unlikely to provide meaningful relief for the predominant muscular phenotype. Only approximately 8% reported sleeping with a persistent bedroom light source, making light-at-night an improbable group-level driver of symptoms. From a mechanistic standpoint, future work should link questionnaire-derived muscular fatigue to in vivo markers of skeletal-muscle oxidative capacity (e.g., 31phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy), mitochondrial DNA integrity and systemic cytokine profiles, and test targeted interventions (e.g., supervised aerobic/strength programs or agents modulating mitochondrial bioenergetics).

Our conclusions must be viewed through several methodological lenses. All outcomes relied on self-reported questionnaires, accordingly, statements about chronotype refer to self-reported preference rather than biologically measured circadian timing, without objective corroboration from muscle performance tests, actigraphy or melatonin-phase measurements, so recall bias and day-to-day variability may have influenced results. The PSC sample was smaller than the PBC and HC groups, which reduces power and may partly explain the non-significant PSC-HC comparison despite a similar direction of effect with regard to fatigue phenotyping. Finally, questionnaires were completed throughout the year without accounting for seasonal changes in daylight, which can alter sleep-wake patterns and perceived energy. These limitations argue for longitudinal, multimodal studies that integrate physiology, neuroimaging and wearable-derived sleep/circadian metrics.

In non-cirrhotic cholestatic disease, fatigue presents predominantly with a muscular phenotype. This pattern is evident in PBC and directionally similar in PSC, despite comparable global fatigue scores across groups. Multivariable modelling confirms that, compared with PBC, HC have markedly lower odds of muscular fatigue, whereas PSC does not differ from PBC after adjustment; age independently slightly increases the likelihood of a muscular phenotype. These observations, together with the absence of associations with routine liver biochemistry, fibrosis stage, or current cholestasis-directed therapy, indicate that the dominant fatigue signal is decoupled from conventional disease activity metrics and not explained by demographics or occupational factors.

By contrast, on questionnaire measures (MEQ-SA, ESS) we observed no group-level differences in chronotype or daytime alertness. MEQ-SA scores clustered in the intermediate range and, in adjusted analyses, age - rather than disease group - was the only independent predictor of chronotype, while daytime sleepiness remained low across groups. Because objective circadian markers (e.g., actigraphy, cosinor analysis of rest-activity rhythms, or dim-light melatonin onset) were not collected, subtle circadian misalignment cannot be excluded; our inferences pertain to self-reported chronotype rather than biologically measured circadian rhythmicity. Taken together, this pattern could suggest that marked sleep-wake disruption in decompensated cirrhosis may not be intrinsic to early cholestatic disease but could arise later with accumulating neuroinflammatory and metabolic insults.

Clinically, these data support systematic screening for fatigue phenotype and the adoption of targeted interventions aligned with a muscular presentation - such as structured aerobic/strength rehabilitation and strategies addressing skeletal-muscle bioenergetics or autonomic balance - rather than reliance on cholestasis-focused therapies to relieve fatigue. From a research standpoint, priorities include prospective, multi-center studies that integrate patient-reported outcomes with objective neuromuscular and chronobiological measures (e.g., 31phosphorus magnetic resonance spe

| 1. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: The diagnosis and management of patients with primary biliary cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2017;67:145-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 950] [Cited by in RCA: 1013] [Article Influence: 112.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Hirschfield GM, Dyson JK, Alexander GJM, Chapman MH, Collier J, Hübscher S, Patanwala I, Pereira SP, Thain C, Thorburn D, Tiniakos D, Walmsley M, Webster G, Jones DEJ. The British Society of Gastroenterology/UK-PBC primary biliary cholangitis treatment and management guidelines. Gut. 2018;67:1568-1594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in RCA: 243] [Article Influence: 30.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Montali L, Gragnano A, Miglioretti M, Frigerio A, Vecchio L, Gerussi A, Cristoferi L, Ronca V, D'Amato D, O'Donnell SE, Mancuso C, Lucà M, Yagi M, Reig A, Jopson L, Pilar S, Jones D, Pares A, Mells G, Tanaka A, Carbone M, Invernizzi P. Quality of life in patients with primary biliary cholangitis: A cross-geographical comparison. J Transl Autoimmun. 2021;4:100081. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Lynch EN, Campani C, Innocenti T, Dragoni G, Biagini MR, Forte P, Galli A. Understanding fatigue in primary biliary cholangitis: From pathophysiology to treatment perspectives. World J Hepatol. 2022;14:1111-1119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Shahini E, Ahmed F. Chronic fatigue should not be overlooked in primary biliary cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2021;75:744-745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Mells GF, Pells G, Newton JL, Bathgate AJ, Burroughs AK, Heneghan MA, Neuberger JM, Day DB, Ducker SJ, Sandford RN, Alexander GJ, Jones DE; UK-PBC Consortium. Impact of primary biliary cirrhosis on perceived quality of life: the UK-PBC national study. Hepatology. 2013;58:273-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Phaw NA, Dyson JK, Mells G, Jones D. Understanding Fatigue in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66:2380-2386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hollingsworth KG, Newton JL, Taylor R, McDonald C, Palmer JM, Blamire AM, Jones DE. Pilot study of peripheral muscle function in primary biliary cirrhosis: potential implications for fatigue pathogenesis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1041-1048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zajenkowski M, Jankowski KS, Stolarski M. Why do evening people consider themselves more intelligent than morning individuals? The role of big five, narcissism, and objective cognitive ability. Chronobiol Int. 2019;36:1741-1751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Björnsson E, Simren M, Olsson R, Chapman RW. Fatigue in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:961-968. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | van Munster KN, Dijkgraaf MGW, Oude Elferink RPJ, Beuers U, Ponsioen CY. Symptom patterns in the daily life of PSC patients. Liver Int. 2022;42:1562-1570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Dyson JK, Elsharkawy AM, Lamb CA, Al-Rifai A, Newton JL, Jones DE, Hudson M. Fatigue in primary sclerosing cholangitis is associated with sympathetic over-activity and increased cardiac output. Liver Int. 2015;35:1633-1641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Nijrolder I, van der Windt D, de Vries H, van der Horst H. Diagnoses during follow-up of patients presenting with fatigue in primary care. CMAJ. 2009;181:683-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yoon JH, Park NH, Kang YE, Ahn YC, Lee EJ, Son CG. The demographic features of fatigue in the general population worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1192121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Knoop V, Cloots B, Costenoble A, Debain A, Vella Azzopardi R, Vermeiren S, Jansen B, Scafoglieri A, Bautmans I; Gerontopole Brussels Study group. Fatigue and the prediction of negative health outcomes: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2021;67:101261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Reyes-Gibby CC, Aday LA, Anderson KO, Mendoza TR, Cleeland CS. Pain, depression, and fatigue in community-dwelling adults with and without a history of cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;32:118-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Schwarz R, Krauss O, Hinz A. Fatigue in the general population. Onkologie. 2003;26:140-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Roenneberg T, Wirz-Justice A, Merrow M. Life between clocks: daily temporal patterns of human chronotypes. J Biol Rhythms. 2003;18:80-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1481] [Cited by in RCA: 1794] [Article Influence: 78.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Aschoff J. Circadian timing. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1984;423:442-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Montaruli A, Castelli L, Mulè A, Scurati R, Esposito F, Galasso L, Roveda E. Biological Rhythm and Chronotype: New Perspectives in Health. Biomolecules. 2021;11:487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 42.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hastings MH, Reddy AB, Maywood ES. A clockwork web: circadian timing in brain and periphery, in health and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:649-661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 868] [Cited by in RCA: 918] [Article Influence: 39.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ikeda M, Sugiyama T, Wallace CS, Gompf HS, Yoshioka T, Miyawaki A, Allen CN. Circadian dynamics of cytosolic and nuclear Ca2+ in single suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons. Neuron. 2003;38:253-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yamazaki S, Numano R, Abe M, Hida A, Takahashi R, Ueda M, Block GD, Sakaki Y, Menaker M, Tei H. Resetting central and peripheral circadian oscillators in transgenic rats. Science. 2000;288:682-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1379] [Cited by in RCA: 1437] [Article Influence: 55.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Qiu J, Dai T, Tao H, Li X, Luo C, Sima Y, Xu S. Inhibition of Expression of the Circadian Clock Gene Cryptochrome 1 Causes Abnormal Glucometabolic and Cell Growth in Bombyx mori Cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:5435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Mormont MC, Waterhouse J. Contribution of the rest-activity circadian rhythm to quality of life in cancer patients. Chronobiol Int. 2002;19:313-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Tranah GJ, Blackwell T, Stone KL, Ancoli-Israel S, Paudel ML, Ensrud KE, Cauley JA, Redline S, Hillier TA, Cummings SR, Yaffe K; SOF Research Group. Circadian activity rhythms and risk of incident dementia and mild cognitive impairment in older women. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:722-732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 311] [Cited by in RCA: 407] [Article Influence: 29.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Tranah GJ, Blackwell T, Ancoli-Israel S, Paudel ML, Ensrud KE, Cauley JA, Redline S, Hillier TA, Cummings SR, Stone KL; Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Circadian activity rhythms and mortality: the study of osteoporotic fractures. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:282-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Adan A, Archer SN, Hidalgo MP, Di Milia L, Natale V, Randler C. Circadian typology: a comprehensive review. Chronobiol Int. 2012;29:1153-1175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 714] [Cited by in RCA: 941] [Article Influence: 67.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Montagnese S, Nsemi LM, Cazzagon N, Facchini S, Costa L, Bergasa NV, Amodio P, Floreani A. Sleep-Wake profiles in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2013;33:203-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Montagnese S, Middleton B, Mani AR, Skene DJ, Morgan MY. Sleep and circadian abnormalities in patients with cirrhosis: features of delayed sleep phase syndrome? Metab Brain Dis. 2009;24:427-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2022;77:761-806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 56.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 32. | Castera L, Forns X, Alberti A. Non-invasive evaluation of liver fibrosis using transient elastography. J Hepatol. 2008;48:835-847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 972] [Cited by in RCA: 1101] [Article Influence: 61.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 33. | Aguilar MT, Chascsa DM. Update on Emerging Treatment Options for Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Hepat Med. 2020;12:69-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Phaw NA, Leighton J, Dyson JK, Jones DE. Managing cognitive symptoms and fatigue in cholestatic liver disease. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;15:235-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Newton JL, Hollingsworth KG, Taylor R, El-Sharkawy AM, Khan ZU, Pearce R, Sutcliffe K, Okonkwo O, Davidson A, Burt J, Blamire AM, Jones D. Cognitive impairment in primary biliary cirrhosis: symptom impact and potential etiology. Hepatology. 2008;48:541-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Khanna A, Leighton J, Lee Wong L, Jones DE. Symptoms of PBC - Pathophysiology and management. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;34-35:41-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Mosher VAL, Swain MG, Pang JXQ, Kaplan GG, Sharkey KA, MacQueen GM, Goodyear BG. Primary Biliary Cholangitis Alters Functional Connections of the Brain's Deep Gray Matter. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2017;8:e107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | McDonald C, Newton J, Lai HM, Baker SN, Jones DE. Central nervous system dysfunction in primary biliary cirrhosis and its relationship to symptoms. J Hepatol. 2010;53:1095-1100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Duszynski CC, Avati V, Lapointe AP, Scholkmann F, Dunn JF, Swain MG. Near-Infrared Spectroscopy Reveals Brain Hypoxia and Cerebrovascular Dysregulation in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Hepatology. 2020;71:1408-1420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/