Published online Feb 27, 2026. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v18.i2.113775

Revised: October 2, 2025

Accepted: December 10, 2025

Published online: February 27, 2026

Processing time: 162 Days and 22.3 Hours

Anticoagulation therapy is recommended during the acute or subacute stage for patients with pyrrolizidine alkaloid-hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (PA-HSOS). Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts (TIPS) is suggested as a step-up treatment when patients do not respond to anticoagulants. However, more evidence of the efficacy of TIPS is needed.

To evaluate the effect of TIPS in these patients.

Between January 2013 and September 2020, we retrospectively enrolled patients with PA-HSOS who did not respond to short-term anticoagulation therapy at four hospitals. The patients were divided into a TIPS treatment group and an anticoagulation therapy group. Baseline information and clinical characteristics were collected and recorded. Survival in both groups was the primary study endpoint and the risk factors for patient death were further analyzed.

A total of 99 patients were enrolled according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria (63 in the TIPS group and 36 in the anticoagulation therapy group). There were 17 deaths during the median follow-up time of 32.5 months. Treatment, age, aspartate aminotransferase, and serum total bilirubin were independent risk factors for predicting death. The survival of patients in the TIPS group was significantly greater than that of patients in the continuing anticoagulation therapy group (P = 0.028). When stratified by the Drum-Tower Severity Scoring, in the TIPS group, mild and moderate patients had better outcomes than severe patients.

TIPS can improve the transplant-free survival rate in patients with PA-HSOS who do not respond to short-term anticoagulation therapy, and patients with mild and moderate Drum-Tower Severity Scoring grade can benefit from TIPS.

Core Tip: Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts (TIPS) could improve the survival rate of pyrrolizidine alkaloid-hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome patients who have no response to initial short-term anticoagulation therapy, and patients with Drum-Tower Severity Scoring of mild and moderate grade could benefit from TIPS. More active and earlier TIPS can be considered in patients with no response to anticoagulation therapy.

- Citation: Tu JJ, Zhang H, Kong DR, Feng YH, Yu YC, Li TS, Zhang F, Zhang W, Xu H, Yin Q, Wang L, Zhang M, Xiao JQ, Zhuge YZ. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt improves survival in anticoagulation-resistant hepatic sinusoidal obstructive syndrome patients: A multicenter retrospective study. World J Hepatol 2026; 18(2): 113775

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v18/i2/113775.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v18.i2.113775

Hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (HSOS), also known as hepatic veno-occlusive disease, is a vascular disorder of the liver. It is characterized by endothelial cell edema, necrosis, and detachment within the small hepatic sinusoids and interlobular veins, leading to intrahepatic congestion, portal hypertension and liver dysfunction[1]. HSOS can be divided into hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT)-HSOS and pyrrolizidine alkaloid (PA)-HSOS according to its etiology. HSCT-HSOS is a serious, potentially fatal complication after HSCT, but with the adjustment of chemotherapy drugs and strategies to prevent this disease, the incidence of HSCT-HSOS has decreased significantly[2-4]. However, as plants containing PAs are widely distributed across the plant kingdom and humans have easy access to PA-containing or PA-contaminated foodstuffs, patients with PA-HSOS have been increasingly reported. This is especially true in China and South Asia, where local people have a tradition of consuming herbal medicine for disease treatment and health care[5-7].

For acute or subacute patients with PA-HSOS, the consensus treatment is anticoagulation-transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts (TIPS) stepwise therapy[8]. Recent studies and our data revealed that the survival rate of patients with PA-HSOS who do not respond to anticoagulation therapy is approximately 30%-40%, while the overall survival of patients who receive anticoagulation-TIPS stepwise therapy was approximately 90%[9,10]. Therefore, TIPS is thought to play an important role in increasing survival. However, most of the articles contributing to these survival statistics were small-sample studies or single-arm studies[11-14]. In view of the lack of direct and high-quality evidence that TIPS can improve the prognosis of patients with no response to anticoagulation therapy, some researchers still doubt the efficacy of TIPS in PA-HSOS patients[15,16].

In this multicenter retrospective study, we first included patients with PA-HSOS who did not respond to initial short-term anticoagulation therapy, and then compared the prognosis of patients who received TIPS or continuous anticoagulation therapy. The aim of this study was to validate the role of TIPS in patients with PA-HSOS who do not respond to anticoagulation therapy and to analyze their possible causes of and risk factors for death.

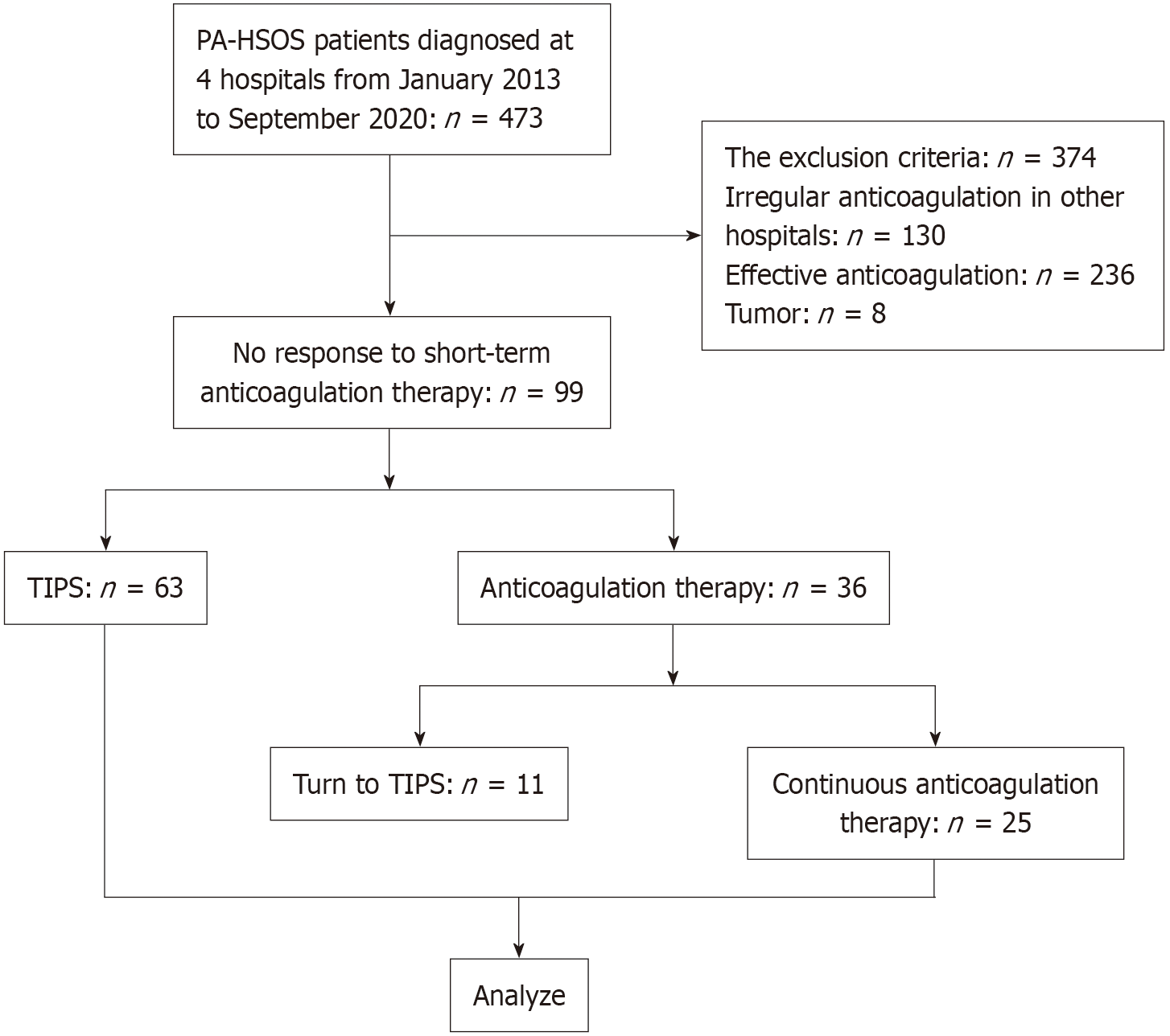

Between January 2013 and September 2020, a total of 473 patients were diagnosed with PA-HSOS at Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, the General Hospital of Eastern Theater Command, the Second Hospital of Nanjing and the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University. The diagnosis of PA-HSOS was made in accordance with the ‘Nanjing criteria’, which required a confirmed history of PA-containing plant intake and the following three conditions: (1) Clinical manifestations such as abdominal distention and/or pain in the hepatic region, ascites, or hepatomegaly; (2) Evidence of liver injury, indicated by abnormal liver function tests or elevated serum total bilirubin; and (3) Imaging support from contrast-enhanced computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, or pathological confirmation. The characteristic pathological findings include sinusoidal endothelial cell swelling, detachment, and necrosis in hepatic zone III, accompanied by marked sinusoidal congestion, which should exclude other known causes of liver injury[8]. These patients all received initial anticoagulation treatment for 2-3 weeks, and 99 patients were found to be unresponsive to short-term anticoagulation therapy and were included in this retrospective study. No response to short-term anticoagulation therapy was defined as follows: (1) Clinical manifestations: No relief of abdominal distension; (2) Laboratory tests: Serum total bilirubin progressively increased or increased by more than 5 mg/dL and progressively deteriorating renal function; and (3) Imaging: Portal vein velocity (PVV) less than 10 cm/second or an increase in PVV < 10% from baseline. We also used the Drum-Tower Severity Scoring (DTSS) to evaluate the severity of the symptoms in the patients with PA-HSOS. The DTSS considers the fibrinogen level, total bilirubin level, PVV, and aspartate aminotransferase (AST). Patients with scores of 4-6 were defined as mild, those with scores of 7-10 were moderate, and those with scores of 11 to 16 were severe[17]. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Age between 18 years and 80 years; (2) Clear diagnosis of PA-HSOS (according to the ‘Nanjing criteria’); and (3) Unresponsive to initial short-term anticoagulation therapy. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients who refused follow-up or were lost to follow-up; (2) Patients with missing clinical data; (3) Patients who had received irregular anticoagulation therapy; and (4) Patients with malignant tumors or other severe diseases. The flowchart is shown in Figure 1.

The patients diagnosed with PA-HSOS were first treated with initial anticoagulation therapy and concurrent supportive therapy (such as liver protection, diuretics and albumin infusion) for 2-3 weeks. The anticoagulation protocol consisted of low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) alone (4000 IU q12h, subcutaneous injection) or LMWH-warfarin combination therapy. LMWH-warfarin combination therapy was usually recommended if the patient had a baseline international normalized ratio (INR) less than 1.5 and a platelet count greater than 50 × 109/L. Warfarin was started orally at 1.5 mg daily and was subsequently adjusted to obtain a target INR of 2.0-3.0. Ultrasound and blood tests were performed every week to evaluate the portal vein blood flow velocity and liver function. If a patient did not respond to the initial short-term anticoagulation therapy, TIPS was considered. If patients did not accept TIPS, they continued to be treated with the original conservative therapy (anticoagulation and supportive therapy).

The four centers followed the uniform rules of the TIPS procedure[18-20]. Following successful cannulation of the right internal jugular vein, access was achieved. A catheter was then advanced into the hepatic and portal veins to create a stent channel. Before stent deployment, the portal pressure gradient (PPG) was measured. A covered stent (an 8 mm Viatorr stent or an 8 mm Fluency stent), combined with a Luminexx bare metal stent, was deployed to support the parenchymal channel. The stent length was determined using a calibrated marker catheter. After balloon dilatation of the stent, the PPG was measured again. Doppler ultrasonography was carried out three to five days after TIPS to assess stent patency.

The clinical data included demographic characteristics, history of liver diseases, history of PA intake, underlying diseases, clinical symptoms, and hepatic encephalopathy (HE). The laboratory tests included white blood cells, hemoglobin, platelets, AST, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, serum total bilirubin (STB), serum direct bilirubin, albumin, cholinesterase, blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, fibrinogen, and PPG.

The baseline characteristics and follow-up data were extracted from the medical records. The patient follow-up frequency was set at 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months after TIPS and every 6 months thereafter. The follow-up endpoint was defined as death or the end of the study (March 2021). Each visit included clinical signs and symptoms, routine blood tests, liver function tests, blood ammonia tests, coagulation tests, ultrasound, or computed tomography scans when necessary, according to the patient’s treating physicians.

All the statistics were analyzed by IBM SPSS Statistics 25.0 (Armonk, NY, United States) and R studio. For parameters with a normal distribution, the variables are expressed as the mean ± SD and were compared by independent sample t tests. For nonparametric distributions, the variables are expressed as medians [interquartile ranges (IQR)], and group comparisons were performed using the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables are presented as n (%) and were compared by χ² tests or Fisher’s exact test. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard models were used to evaluate the independent risk factors for death, and the hazard ratio and 95%CI were calculated. The overall transplant-free survival and survival between the two different treatments are described with Kaplan-Meier curves, and the differences were tested using the log-rank test. A P value of < 0.05 denoted a significant difference. Statistical analysis for nomogram construction and adjusted survival curves were performed in R software[21,22].

Among the 473 patients with PA-HSOS treated in the four hospitals between January 2013 and September 2020, 99 patients who did not respond to initial anticoagulation therapy were included in this research. They were divided into 2 groups: The TIPS group (n = 63) and the anticoagulation therapy group (n = 36). In the anticoagulation therapy group, 25 patients continued anticoagulation treatment until death or the end of the study, and 11 patients did not achieve satisfactory results and ultimately underwent TIPS.

All the baseline information is presented in Table 1. We compared the TIPS group (n = 63) and the continued anticoagulation therapy group (n = 25) until the end of the follow-up. Among the 88 patients, the average age was approximately 65 years, and 72.7% were male. The common clinical presentations were abdominal distension and ascites (100%), pain in the liver area (17.0%), oliguresis (70.5%), loss of appetite (65.9%), edema of the lower extremities (15.9%) and chest tightness (11.4%). Overall, 27/88 (30.7%) had a drinking history, and 47/88 (53.4%) had underlying diseases such as diabetes, hypertension and cerebral infarction. However, neither the symptoms nor the underlying diseases of the patients differed significantly between the two groups (P > 0.1). The proportions of abnormal serological biochemical indicators such as blood tests, anticoagulation function, liver and renal function and hepatic encephalopathy at baseline were also similar between the groups (P > 0.1). The only difference between the two groups was the coagulation function of activated partial thromboplastin time and prothrombin time (P < 0.05). In the aspect of the patients’ severity evaluation, a total of 66 patients were recognized as mild or moderate, and 18 patients were recognized as severe. In the TIPS group, the PPG clearly decreased from 25 mmHg (IQR: 21.0-33.0 mmHg) to 9 mmHg (IQR: 6.00-22.25 mmHg).

| Total (n = 88) | Anticoagulation therapy (n = 25) | TIPS (n = 63) | P value | |

| Age | 64.67 ± 8.41 | 66.05 ± 9.20 | 64.28 ± 8.29 | 0.592 |

| Male sex | 64 (72.7) | 18 (72.0) | 46 (73.0) | 0.923 |

| Hypertension | 40 (45.5) | 13 (52.0) | 27 (42.9) | 0.437 |

| Diabetes | 16 (18.2) | 4 (16.0) | 12 (19.0) | 0.978 |

| Cerebral infarction | 7 (8.0) | 3 (12.0) | 4 (6.3) | 0.400 |

| Drinking | 27 (30.7) | 7 (28.0) | 20 (31.7) | 0.731 |

| Abdominal distension | 88 (100) | 25 (100) | 63 (100) | 1.000 |

| Abdominal pain | 15 (17.0) | 4 (16.0) | 11 (17.5) | 0.869 |

| Oliguria | 62 (70.5) | 20 (80.0) | 42 (66.7) | 0.216 |

| Poor appetite | 58 (65.9) | 15 (60.0) | 43 (68.3) | 0.461 |

| Chest tightness | 10 (11.4) | 2 (8.0) | 8 (12.7) | 0.800 |

| Edema of both lower extremities | 14 (15.9) | 6 (24.0) | 8 (12.7) | 0.191 |

| Baseline OHE | 6 (6.8) | 2 (8.0) | 4 (6.3) | 0.550 |

| Newly OHE | 9 (10.2) | 0 (0) | 9 (14.3) | - |

| White blood cells (109/L) | 7.03 ± 2.90 | 6.60 ± 2.38 | 7.20 ± 3.07 | 0.391 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 150.01 ± 17.12 | 151.96 ± 13.34 | 149.27 ± 18.40 | 0.516 |

| Platelets (109/L) | 100.0 (73.0-125.0) | 104.50 (86.75-156.50) | 97.0 (72.0-119.0) | 0.080 |

| ALT (U/L) | 33.25 (23.03-53.83) | 34.80 (22.95-51.20) | 32.80 (23.00-61.20) | 0.614 |

| AST (U/L) | 50.00 (36.73-64.00) | 49.70 (35.55-57.00) | 50.30 (37.10-68.90) | 0.473 |

| ALT/AST | 0.75 ± 0.24 | 0.73 ± 0.19 | 0.77 ± 0.25 | 0.495 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 3.26 (2.08-4.81) | 3.07 (1.79-3.99) | 3.26 (2.13-4.84) | 0.462 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 2.06 (1.20-3.43) | 2.12 (1.10-3.31) | 2.04 (1.21-3.50) | 0.736 |

| Gamma-glutamyl transferase (U/L) | 87.0 (60.0-153.30) | 91.20 (64.85-187.38) | 79.80 (55.60-138.10) | 0.273 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 115.40 (88.90-162.0) | 117.85 (92.20-185.98) | 113.0 (88.70-153.60) | 0.161 |

| Cholinesterase (U/L) | 2.21 ± 0.89 | 2.23 ± 0.73 | 2.14 ± 0.81 | 0.337 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 34.12 ± 3.53 | 34.44 ± 4.07 | 33.99 ± 3.32 | 0.589 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mmol/L) | 6.70 (5.43-8.58) | 6.30 (5.70-8.05) | 6.80 (5.20-9.00) | 0.821 |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/L) | 78.50 (63.25-95.75) | 90.0 (70.0-106.0) | 77.0 (62.0-92.0) | 0.167 |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time (seconds) | 48.93 ± 14.78 | 56.80 ± 17.10 | 45.89 ± 12.67 | 0.009 |

| Prothrombin time (seconds) | 18.40 (14.90-26.00) | 25.80 (16.55-33.83) | 16.50 (14.50-21.90) | 0.009 |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 2.05 ± 0.76 | 2.28 ± 0.71 | 1.97 ± 0.77 | 0.112 |

| Portal vein velocity, cm/second | 12.37 ± 5.54 | 12.78 ± 5.14 | 12.19 ± 5.74 | 0.682 |

| Drum-Tower Severity Scoring grade (mild and moderate/severe) | 66/18 | 21/2 | 45/16 | 0.134 |

| PPG before TIPS (mmHg) | - | - | 25.0 (21.0-33.0) | - |

| PPG after TIPS (mmHg) | - | - | 9.00 (6.00-22.25) | - |

| Median follow-up time (m) | 32.50 (13.64-53.17) | 30.00 (3.70-58.93) | 32.60 (15.17-52.47) | 0.657 |

The median follow-up time of the whole cohort was 32.50 months (IQR: 13.64-53.17 months). The follow-up times were 30.00 months (IQR: 3.70-58.93 months) in the continued anticoagulation therapy group and 32.60 months (IQR: 15.17-52.47 months) in the TIPS group (P = 0.657).

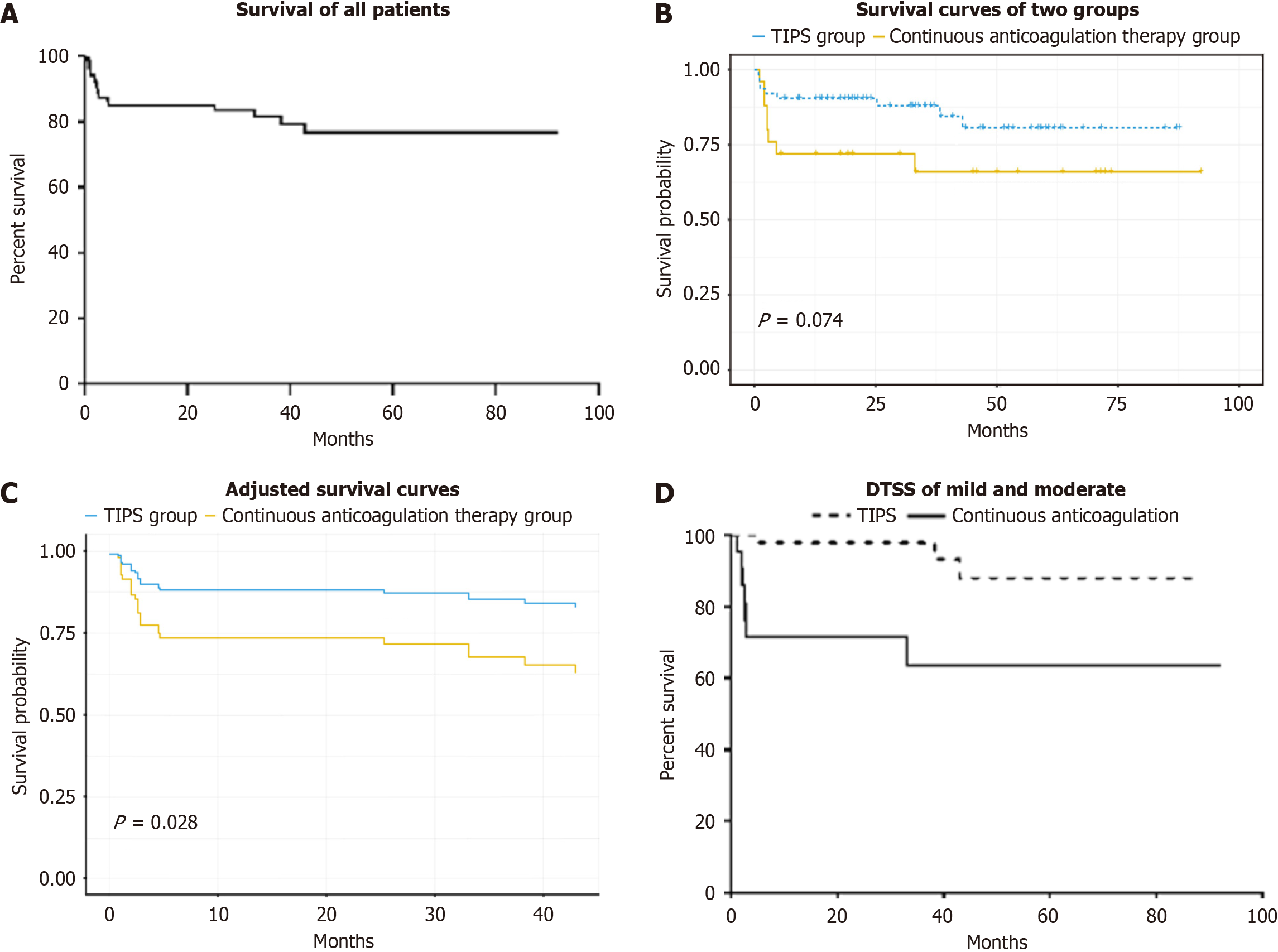

The 1-year, 2-year and 3-year overall survival rates were 85.2%, 85.2% and 81.5%, respectively (Figure 2A). As shown in Figure 2B, the survival curves suggested a trend toward greater survival in the TIPS group than in the continuous anticoagulation therapy group, but it did not have a statistical significance (P = 0.074). Then, we drawn an adjusted survival curve, as shown in Figure 2C, and revealed that survival was significantly greater in the TIPS group than in the continuous anticoagulation therapy group (P = 0.028). In patients with mild and moderate DTSS grade, the 1-year and 3-year cumulative survival rates of the patients who underwent TIPS were both 97.8%, whereas the 1-year and 3-year cumulative survival rates of the patients who received continued anticoagulation therapy were 71.4% and 63.5%, respectively (Figure 2D). The 1-year and 3-year cumulative survival rates were clearly higher in the TIPS group than in the continued anticoagulation therapy group (P = 0.003). In patients with severe DTSS grade, survival did not sig

During the 32.60-month median follow-up time in the TIPS group, 9 patients died. Two died from multiorgan dys

The technical success rate of TIPS was 100%. Two patients in the continuous anticoagulation therapy group and 4 patients in the TIPS group had HE at baseline. During the follow-up period, the 1-month and 5-year probabilities of overt hepatic encephalopathy (OHE) were 12.7% and 14.3%, respectively, in the TIPS group. Nine patients had new-onset OHE after TIPS, eight of whom recovered after drug therapy (lactulose and rifaximin), and only one patient experienced refractory OHE and underwent stent blocking 1 year after TIPS. Stent dysfunction was detected in one patient 2 years after TIPS and recanalization was performed. No TIPS stent thrombosis occurred during the follow-up period.

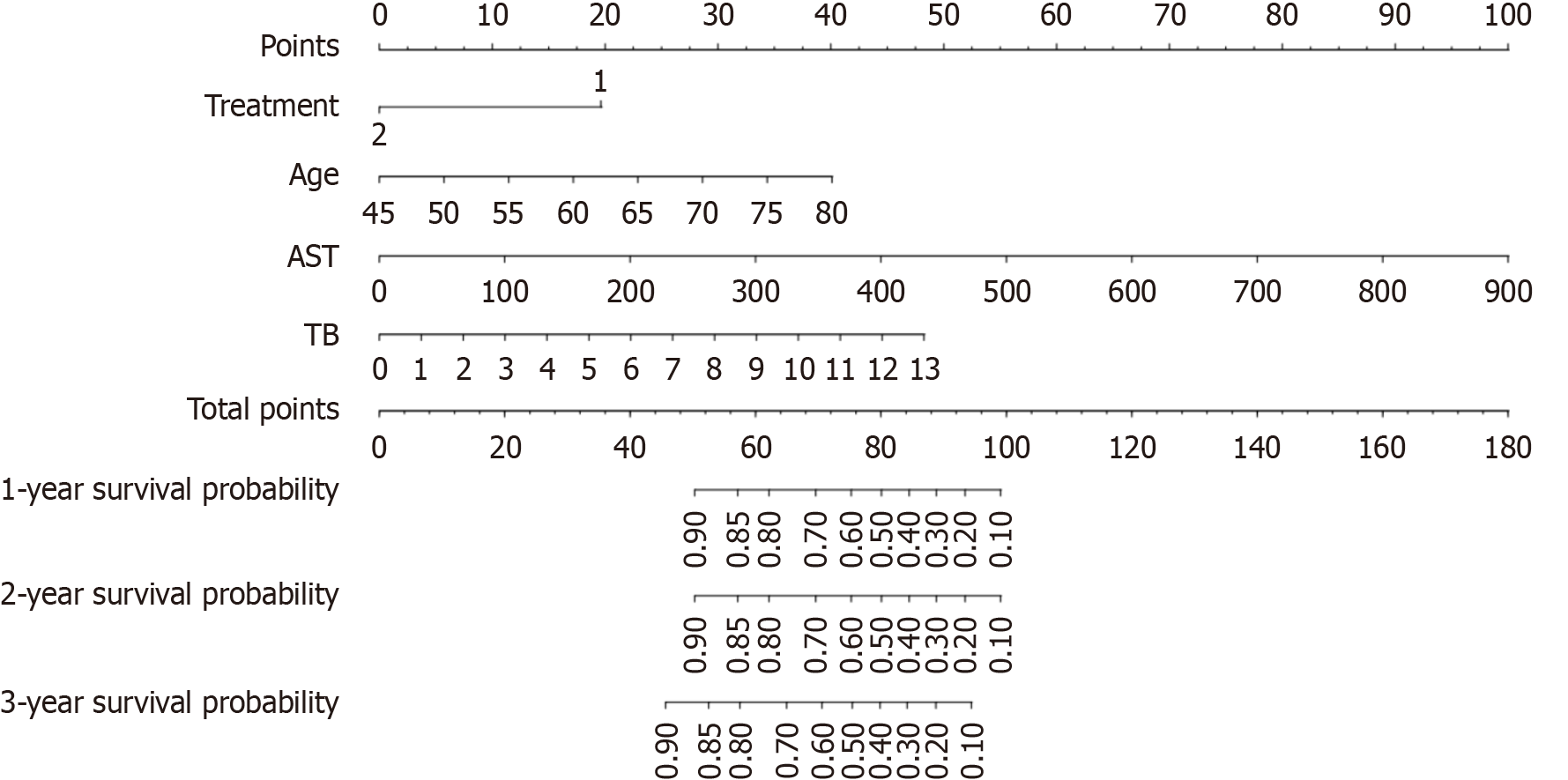

By univariate Cox proportional hazard models, we found that factors such as age; treatment with TIPS or continuous anticoagulation therapy; and high levels of alanine aminotransferase, AST, STB, serum direct bilirubin and cholinesterase may be associated with a poor prognosis. Our multivariate analysis incorporated variables that were statistically significant (P < 0.05) in the univariate Cox model as well as clinically relevant factors that may influence prognosis, such as treatment and age. We included age, treatment, STB, AST and cholinesterase in the multivariate Cox model and found that treatment, AST, STB and age were independent risk factors for death (Table 2). The risk factors were further visualized by a nomogram, and the nomogram-derived probabilities of the 1-year and 2-year survival rates of patients with PA-HSOS were plotted (Figure 3). The c-index of the nomogram for prediction was 0.79. This model contains four variables, which are located on each variable axis. We can obtain the point received for the value of each variable by drawing a line up to the point axis, and the sum of these points corresponds to the total point axis. The total points determine the likelihood for each individual’s 1-year, 2-year and 3-year survival by drawing a line downward to the survival axes.

| Univariate analysis | P value | Multivariate analysis | P value | |

| Age | 1.063 (0.995-1.136) | 0.068 | 1.067 (1.000-1.137) | 0.049 |

| Sex | 0.588 (0.169-2.046) | 0.403 | ||

| Treatment (transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts/anticoagulation therapy) | 0.428 (0.165-1.111) | 0.081 | 0.321 (0.116-0.886) | 0.028 |

| White blood cells | 1.091 (0.959-1.242) | 0.187 | ||

| Hemoglobin | 1.033 (1.000-1.067) | 0.052 | ||

| Platelets | 0.992 (0.978-1.005) | 0.225 | ||

| Total bilirubin | 1.286 (1.115-1.483) | 0.001 | 1.211 (1.035-1.418) | 0.017 |

| Direct bilirubin | 1.372 (1.119-1.682) | 0.002 | ||

| AST | 1.007 (1.002-1.012) | 0.009 | 1.007 (1.001-1.014) | 0.028 |

| ALT | 1.008 (1.001-1.015) | 0.020 | ||

| ALT/AST | 0.323 (0.035-3.002) | 0.320 | ||

| Alkaline phosphatase | 0.999 (0.993-1.005) | 0.813 | ||

| Gamma-glutamyl transferase | 0.998 (0.991-1.004) | 0.483 | ||

| Albumin | 1.011 (0.878-1.164) | 0.881 | ||

| Cholinesterase | 0.437 (0.216-0.883) | 0.021 | 0.524 (0.218-1.260) | 0.149 |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 1.046 (0.942-1.160) | 0.400 | ||

| Serum creatinine | 1.004 (0.997-1.011) | 0.282 | ||

| Fibrinogen | 0.638 (0.274-1.483) | 0.297 | ||

| Portal vein velocity | 1.011 (0.922-1.110) | 0.811 |

Previous studies showed that patients with PA-HSOS could achieve a higher survival rate with anticoagulation therapy than with symptom-based conservative medication, and an anticoagulation-TIPS stepwise strategy could further improve survival[8,9]. However, to date, no direct or high-quality evidence has demonstrated that TIPS can effectively increase the survival rate of patients with PA-HSOS who are unresponsive to anticoagulants. Some recent studies agreed that TIPS was associated with a decreased risk of refractory ascites and portal hypertension[9,18], whereas others reported that TIPS had no additional effect on increasing the survival rate[10]. Therefore, the effect of TIPS on PA-HSOS remains controversial.

In our previous study, we concluded that a prothrombin time > 17.85 s at baseline and a serum total bilirubin concentration > 9 mg/dL at 5 days after TIPS were independent risk factors for patients with PA-HSOS[18]. Regrettably, although an elevated bilirubin level 5 days after TIPS can indicate a poor post-TIPS prognosis, it has no decision-making role in evaluating whether TIPS is worthy of being performed. Furthermore, the inclusion of post-TIPS predictors cannot achieve good predictive power in the population without TIPS, and it is impossible to know the prognosis of this same population of patients. A similar multicentre retrospective study[23] also concluded that TIPS decreased mortality, but not in patients who did not respond to anticoagulants. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate whether TIPS can improve the survival outcomes of patients with PA-HSOS who do not respond to initial short-term anticoagulation therapy and identify who will benefit from TIPS[15]. In this multicenter retrospective study, we demonstrated that patients who underwent TIPS could achieve a better outcome than those who received continued anticoagulation therapy among the population of patients who did not respond to the initial 2 weeks of anticoagulation treatment.

Our study revealed that the 1-year, 2-year and 3-year overall survival rates were 85.2%, 85.2% and 81.5%, respectively. Nine patients in the TIPS group died, and the causes included MODs (n = 2), liver failure (n = 5) and bleeding (n = 2). Eight patients in the continued anticoagulation group died, and the causes included liver failure (n = 6), bleeding (n = 1) and cardiac disease (n = 1). The most common cause of death in either group was further deterioration of liver function. Additionally, we found that patients in the TIPS group died earlier than those in the anticoagulation therapy group did. Inflammatory factors and bacteria enter the peripheral circulation through the stent because of the destruction of the liver-intestinal barrier[24-26]. In the continuous anticoagulation therapy group, an inflammatory storm also occurs but is limited to the portal system. Therefore, we plan to investigate whether early application of intestinal mucosal protective drugs to treat critically ill patients can improve survival. Our related basic research in this area is in progress.

To explore the risk factors for mortality among patients with PA-HSOS, we used univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses and concluded that different treatments (continued anticoagulation therapy/TIPS), AST, total bilirubin, and age were independent risk factors for patients who did not respond to initial anticoagulation therapy. Total bilirubin, AST, age, INR and creatinine have been mentioned in a previous report and were possibly associated with liver and renal function. The most important factor was the choice of treatment. TIPS significantly increased the survival rate and should be recommended when patients fail to respond to the 2-week initial trial of anticoagulation therapy. This may be related to its ability to reduce portal hypertension and refractory ascites. Notably, the administration of medications such as rifaximin and lactulose during and after TIPS did not significantly influence patient survival or quality of life.

To more intuitively display the risk factors, a nomogram was constructed to predict the likelihood of survival of patients with PA-HSOS who do not respond to initial anticoagulation therapy, which allowed us to construct a clearer graph to predict survival and to better communicate with patients about the choice of appropriate treatment. Notably, as patients who underwent TIPS later in their disease course were excluded from the continuous anticoagulation therapy group, we actually overestimated the survival rate of the patients in the anticoagulation group. Many patients who continued to be unresponsive to anticoagulants turned to TIPS. Fortunately, they all survived until the end of our follow-up period.

In addition, we analyzed patient severity according to the DTSS. For mild and moderate patients, treatment with TIPS could have a better outcome than continuous anticoagulation therapy (P = 0.003). The reason is that TIPS could create a crucial time window for the liver's spontaneous recovery by reducing the immediate threat of portal hypertensive complications. Therefore, patients with preserved liver function in the mild and moderate groups are most likely to benefit. For severe patients, there was no significant difference in the TIPS or continuous anticoagulation therapy groups (P = 0.347). These patients have an exceedingly high mortality due to advanced liver injury. At this terminal stage, the hepatocellular necrosis may be irreversible, limiting the potential for any intervention – whether continued anticoagulation or TIPS – to alter the disease course. Liver function can improve once the acute portal hypertension is controlled, but patients may be too sick to withstand a TIPS procedure aimed at helping them survive this critical period. These results can partly explain why TIPS should be recommended with great caution in HSCT-HSOS patients. Also, patients with HSCT-HSOS are too sick and more likely to suffer from severe comorbidities due to their more severe primary hematologic diseases, which maybe the extra reason for the poor efficacy of TIPS in the treatment of HSCT-HSOS reported in some studies[27-30]. This observation precisely underscores the clinical value of the DTSS, which aims not to select the sickest patients for TIPS, but rather to identify the most suitable ones not yet in terminal liver failure to bridge them for recovery. So, it aims to avoid potentially risky procedures in the severe group and unnecessary overtreatment in the mild cases.

A key innovation of our study lies in its multicenter design, leveraging the nation's largest HSOS cohort. We follow up for a long time to study whether TIPS could improve survival in anticoagulation-resistant PA-HSOS patients. Also, by utilizing the DTSS in this population, we provide a novel strategy for optimizing TIPS candidate selection. This precision helps prevent overtreatment and reduces the risk of procedure-related complications. However, although the number of patients is relatively large, the number of patients receiving continuous anticoagulation therapy was limited. Ad

TIPS improved the survival rate of patients with PA-HSOS who did not respond to initial short-term anticoagulation therapy, and patients with mild and moderate DTSS grades can benefit from TIPS. The DTSS provides a rational framework for identifying the intermediate group of patients who will derive the most significant benefit from early TIPS. More active and earlier TIPS can be considered in patients who do not respond to anticoagulation therapy.

The authors would like to thank all the study participants for their voluntary participation.

| 1. | Yang XQ, Ye J, Li X, Li Q, Song YH. Pyrrolizidine alkaloids-induced hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome: Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:3753-3763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 2. | Corbacioglu S, Jabbour EJ, Mohty M. Risk Factors for Development of and Progression of Hepatic Veno-Occlusive Disease/Sinusoidal Obstruction Syndrome. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25:1271-1280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Vascular diseases of the liver. J Hepatol. 2016;64:179-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 653] [Cited by in RCA: 565] [Article Influence: 56.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 4. | Plessier A, Rautou PE, Valla DC. Management of hepatic vascular diseases. J Hepatol. 2012;56 Suppl 1:S25-S38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lin G, Wang JY, Li N, Li M, Gao H, Ji Y, Zhang F, Wang H, Zhou Y, Ye Y, Xu HX, Zheng J. Hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome associated with consumption of Gynura segetum. J Hepatol. 2011;54:666-673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zhu L, Zhang CY, Li DP, Chen HB, Ma J, Gao H, Ye Y, Wang JY, Fu PP, Lin G. Tu-San-Qi (Gynura japonica): the culprit behind pyrrolizidine alkaloid-induced liver injury in China. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2021;42:1212-1222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | He Y, Zhu L, Ma J, Lin G. Metabolism-mediated cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of pyrrolizidine alkaloids. Arch Toxicol. 2021;95:1917-1942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hepatobiliary Disease Collaboration Group of the Digestive Disease Branch of the Chinese Medical Association. [Expert consensus on diagnosis and treatment of pyrrolidine alkaloids-related sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (2017, Nanjing)]. Linchuang Gandanbing Zazhi. 2017;33:1627-1637. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Zhuge YZ, Wang Y, Zhang F, Zhu CK, Zhang W, Zhang M, He Q, Yang J, He J, Chen J, Zou XP. Clinical characteristics and treatment of pyrrolizidine alkaloid-related hepatic vein occlusive disease. Liver Int. 2018;38:1867-1874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Xiang H, Liu C, Xiao Z, Du L, Wei N, Liu F, Song Y. Enoxaparin attenuates pyrrolizidine alkaloids-induced hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome by inhibiting oncostatin M expression. Liver Int. 2023;43:626-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang Y, Qiao D, Li Y, Xu F. Risk factors for hepatic veno-occlusive disease caused by Gynura segetum: a retrospective study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18:156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wu F, Yu J, Gan H, Zhang H, Tian D, Zheng D. Timing and efficacy of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in patients with pyrrolizidine alkaloid-induced hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome. Sci Rep. 2021;11:21743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zhou CZ, Wang RF, Lv WF, Fu YQ, Cheng DL, Zhu YJ, Hou CL, Ye XJ. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for pyrrolizidine alkaloid-related hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:3472-3483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zhang L, Li Q, Makamure J, Zhao D, Liu Z, Zheng C, Liang B. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome associated with consumption of Gynura segetum. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021;21:26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Magaz M, García-Pagán JC. Risk factors of poor prognosis in patients with pyrrolidine alkaloids induced hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in patients with sinusoidal obstruction syndrome, etiology matters. Hepatol Int. 2021;15:568-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Larrue H, Bureau C. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in portal hypertension: How to go further while staying on track? Hepatology. 2023;77:344-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wang X, Zhang W, Zhang M, Zhang F, Xiao J, Yin Q, Han H, Li T, Lin G, Zhuge Y. Development of a Drum Tower Severity Scoring (DTSS) system for pyrrolizidine alkaloid-induced hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome. Hepatol Int. 2022;16:669-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Xiao J, Tu J, Zhang H, Zhang F, Zhang W, Xu H, Yin Q, Yang J, Han H, Wang Y, Zhang B, Peng C, Zou X, Zhang M, Zhuge Y. Risk factors of poor prognosis in patients with pyrrolidine alkaloid-induced hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Hepatol Int. 2021;15:720-729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Patidar KR, Sydnor M, Sanyal AJ. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Clin Liver Dis. 2014;18:853-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Boyer TD. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: current status. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1700-1710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Liang BY, Zhang EL, Li J, Long X, Wang WQ, Zhang BX, Zhang ZW, Chen YF, Zhang WG, Mei B, Xiao ZY, Gu J, Zhang ZY, Xiang S, Dong HH, Zhang L, Zhu P, Cheng Q, Chen L, Zhang ZG, Zhang BH, Dong W, Liao XF, Yin T, Wu DD, Jiang B, Yuan YF, Zhang ZL, Chen YB, Li KY, Lau WY, Chen XP, Huang ZY. A combined pre- and intra-operative nomogram in evaluation of degrees of liver cirrhosis predicts post-hepatectomy liver failure: a multicenter prospective study. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2024;13:198-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Iasonos A, Schrag D, Raj GV, Panageas KS. How to build and interpret a nomogram for cancer prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1364-1370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1306] [Cited by in RCA: 2441] [Article Influence: 135.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wang C, Wang Y, Zhao J, Yang C, Zhu X, Niu H, Sun J, Xiong B. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for the treatment of hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome caused by pyrrolizidine alkaloids: A multicenter retrospective study. Heliyon. 2024;10:e23455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Chopyk DM, Grakoui A. Contribution of the Intestinal Microbiome and Gut Barrier to Hepatic Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:849-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 360] [Article Influence: 60.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zhang P, Zheng L, Duan Y, Gao Y, Gao H, Mao D, Luo Y. Gut microbiota exaggerates triclosan-induced liver injury via gut-liver axis. J Hazard Mater. 2022;421:126707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 31.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Arab JP, Martin-Mateos RM, Shah VH. Gut-liver axis, cirrhosis and portal hypertension: the chicken and the egg. Hepatol Int. 2018;12:24-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Azoulay D, Castaing D, Lemoine A, Hargreaves GM, Bismuth H. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) for severe veno-occlusive disease of the liver following bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;25:987-992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Fried MW, Connaghan DG, Sharma S, Martin LG, Devine S, Holland K, Zuckerman A, Kaufman S, Wingard J, Boyer TD. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for the management of severe venoocclusive disease following bone marrow transplantation. Hepatology. 1996;24:588-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Mohty M, Malard F, Alaskar AS, Aljurf M, Arat M, Bader P, Baron F, Bazarbachi A, Blaise D, Brissot E, Ciceri F, Corbacioglu S, Dalle JH, Dignan F, Huynh A, Kenyon M, Nagler A, Pagliuca A, Perić Z, Richardson PG, Ruggeri A, Ruutu T, Yakoub-Agha I, Duarte RF, Carreras E. Diagnosis and severity criteria for sinusoidal obstruction syndrome/veno-occlusive disease in adult patients: a refined classification from the European society for blood and marrow transplantation (EBMT). Bone Marrow Transplant. 2023;58:749-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Tissot N, Montani D, Seronde MF, Degano B, Soumagne T. Venoocclusive Disease With Both Hepatic and Pulmonary Involvement. Chest. 2020;157:e107-e109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/