Published online Feb 27, 2026. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v18.i2.113464

Revised: October 13, 2025

Accepted: December 9, 2025

Published online: February 27, 2026

Processing time: 166 Days and 6.4 Hours

Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) and laser lithotripsy (LL) are established alternatives for the management of difficult common bile duct (CBD) stones. However, there is limited evidence regarding the efficacy and safety of the latest-generation Dornier Delta III lithotripter. In particular, evidence on the clinical performance of the Dornier Delta III lithotripter is scarce.

To evaluate and compare the efficacy and safety of ESWL performed with the Dornier Delta III and of LL using a single-operator cholangioscope with specific focus on stone clearance rates, number of treatment sessions, and procedure-related adverse events in a large patient cohort.

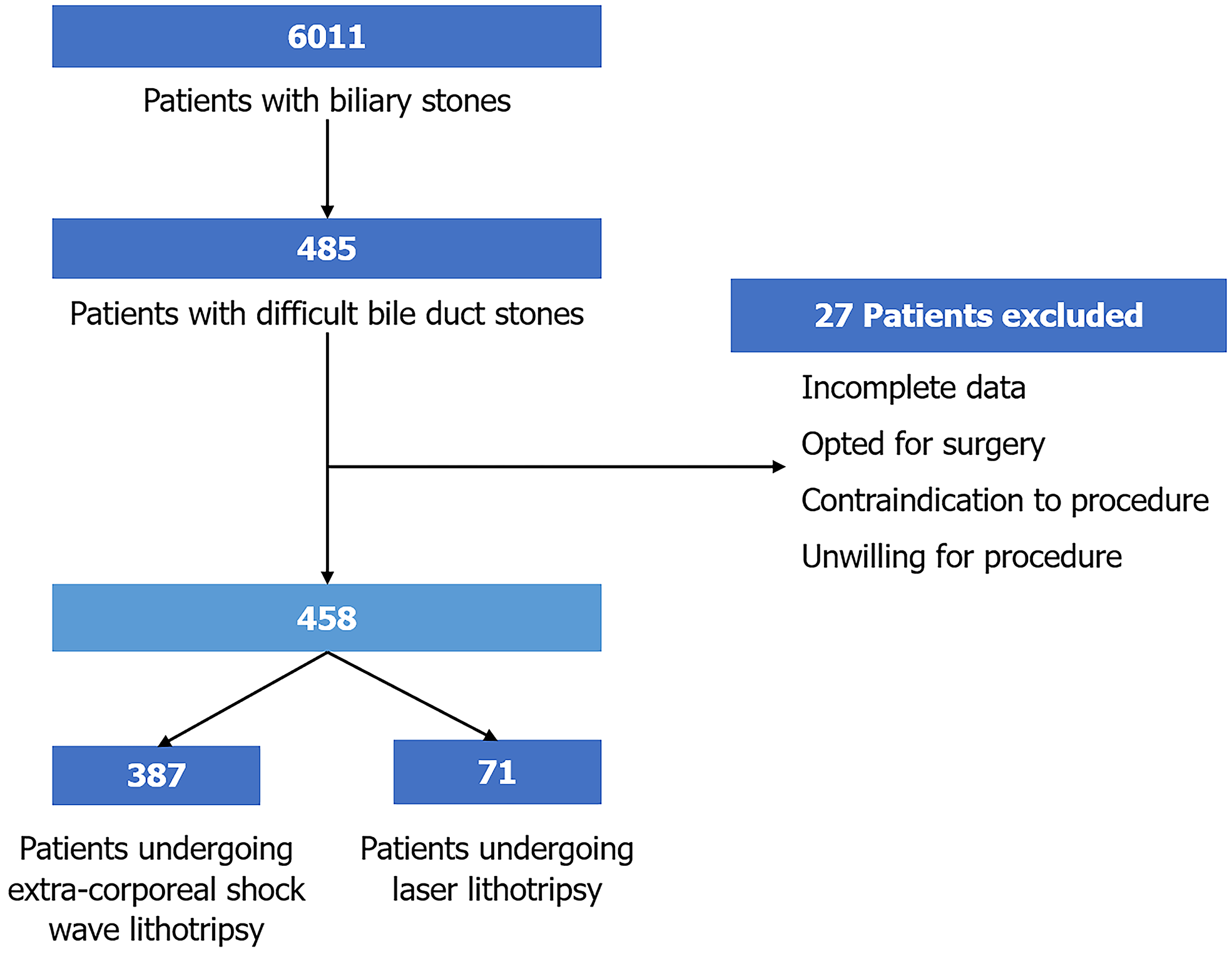

We conducted a retrospective analysis of a prospectively maintained database at AIG Hospitals, Hyderabad, covering the period from January 2019 to December 2022. A total of 458 patients with difficult bile duct stones underwent either ESWL or LL based on clinical discretion. ESWL was performed using the Dornier Delta III lithotripter, whereas LL was carried out with a single-operator cholangioscope in combination with an yttrium-aluminum-garnet laser.

The 387 patients with difficult bile duct stones (mean age 53.8 ± 15.7 years, 58.7% male) underwent ESWL. A single CBD stone was noted in 46.8% of patients while 53.2% patients had multiple stones. Complete duct clearance was achieved in 95.1% of patients, with 68.7% requiring two or more ESWL sessions. Adverse events included cho

ESWL using the latest generation lithotripter and LL provide equally effective and safe alternatives for managing difficult CBD stones, minimizing the need for surgery.

Core Tip: Difficult common bile duct stones pose a significant clinical challenge when standard endoscopic techniques fail. Previous studies have shown significantly better efficacy of laser lithotripsy in managing difficult common bile duct stones as they were compared with the previous generation Dornier delta II system. This study highlighted the role of the latest Dornier Delta III extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy system in improving treatment outcomes, establishing it as a viable, noninvasive alternative to laser lithotripsy.

- Citation: Singla N, Venkata KA, Inavolu P, Memon SF, Koduri KK, Singh AP, Katamareddy T, Darisetty S, Koppoju V, Jagtap N, Kalpala R, Lakhtakia S, Ramchandani M, Tandan M, Reddy DN. Advances in biliary stone management: Latest-generation extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy vs laser lithotripsy for difficult bile duct stones. World J Hepatol 2026; 18(2): 113464

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v18/i2/113464.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v18.i2.113464

Gallstones are a common condition worldwide affecting 10%-15% of the adult population and frequently associated with choledocholithiasis[1-3]. Conventional therapy for common bile duct (CBD) stones involves sphincterotomy and ex

Historically, cholangioscopic techniques have a clearance rate of 88%-93% with an advantage of not requiring fluoroscopic assistance[6,11,12]. It is a safe procedure with a serious adverse event rate of 1%-2%. The adverse events include cholangitis, abdominal pain, pancreatitis, perforation, and bile duct injury[6,11]. The limitations of LL include lack of expertise, technical equipment, and high cost of the procedure[12]. ESWL uses electromagnetic or electrohydraulic energy directed at the calculi from the external body surface to fragment them. The initial lithotripter models used electrohydraulic energy and required general anesthesia, prone positioning, and water immersion. High clearance rates were reported, but newer models were then developed using electromagnetic coils, better focusing, a water cushion instead of water immersion, ultrasound, and digitalized X-ray for localization[13].

Historically, the ductal clearance rate with ESWL has been found to be less than 90%[7,13-16]. Known complications of this procedure are cholangitis and pancreatitis, which occur at a rate 9%-14% in addition to minor adverse effects such as pain and local hematoma formation[7,13-16]. A systemic review of 1969 patients showed higher ductal clearance rate with LL compared with ESWL (95.1% vs 84.5%; P < 0.001)[17]. However, the lithotripters used in the majority of the previous studies were from previous generations, commonly used for kidney stones as well[7,13-16]. The current study is the first to use the Dornier Delta III.

The primary objective was to compare the efficacy of ESWL and LL. This objective was defined as the rate of complete CBD stone clearance confirmed by cholangiography during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). There were three secondary objectives: (1) To compare the number of ERCP sessions required for achieving complete stone clearance with each modality; (2) To assess the procedure-related adverse events, including cholangitis, pancreatitis, and post-sphincterotomy bleeding, classified and graded according to standard definitions; and (3) Need for additional interventions, including surgical referral in cases of incomplete duct clearance.

This was a retrospective analysis of a prospectively maintained database from January 2019 to December 2022 at a tertiary care hospital. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Asian Institute of Gastroenterology (Approval No. AIG/IEC-Post BH&R 46/05.2023-01). Being a retrospective cohort study, no written informed consent was taken from patients for participation in this study. However, all procedures were performed after informed consent, and patient-identifiable data were kept anonymous during collection. The study is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov with ID: NCT055888077.

The inclusion criterion was an indication for ESWL/LL, i.e. patients with difficult CBD stones that could not be extracted by conventional methods such as biliary sphincterotomy, balloon, and sphincteroplasty. Difficult CBD stones were defined as either a large stone (> 15 mm), a large number of stones, difficult anatomy such as distal bile duct stricture, a shorter or sigmoid CBD, acute angulation of CBD, impaction of a stone, or an unusual location such as intrahepatic or in the cystic duct. Patients with pregnancy, coagulopathy that cannot be corrected, or ongoing cholangitis were excluded. The decision of ESWL vs LL was made at the discretion of the endoscopist performing the ERCP procedure.

Diagnosis and initial ERCP: CBD calculi were diagnosed using ultrasound, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, or endoscopic ultrasound. All patients subsequently underwent ERCP with sphincterotomy, followed by attempted stone extraction using a balloon or Dormia basket. In patients with cholangitis a nasobiliary tube (NBT) was placed for drainage, and antibiotics were administered. ESWL or LL was considered only when conventional extraction techniques failed with the choice between modalities left to the discretion of the endoscopist performing ERCP.

ESWL: All patients undergoing ESWL had NBT placement to aid stone visualization. Epidural anesthesia was administered unless contraindicated. ESWL was performed using a third-generation electromagnetic lithotripter (Delta III, Dornier MedTech, Wessling, Germany), equipped with bidimensional fluoroscopy and ultrasound targeting. Radiolucent stones were opacified with contrast injected via NBT while radiopaque stones were targeted directly. The procedure was carried out in the supine position. Shockwave intensity and frequency were gradually increased to optimize fragmentation with the best results achieved at 90 shocks/minute and an intensity of 4 (range: 1-6; 11000-16000 kV). Treatment was initiated at intensity 1 (11000 kV) and increased to 4-5 (14000-15000 kV) over 5-7 min. A maximum of 5000 shocks was delivered per session unless satisfactory fragmentation (< 5 mm) was achieved earlier. Sessions were repeated on consecutive days if required. ERCP for fragment clearance was performed within 48 h of ESWL using balloon or Dormia basket extraction. Biliary stents were placed in patients with partial clearance and subsequently removed after 2-3 months once total clearance was confirmed on cholangiography.

LL: LL was performed using a single-operator cholangioscope (SpyGlass DS, Boston Scientific, MA, United States) in combination with an yttrium-aluminum-garnet laser.

All data were entered into a standardized format in spreadsheets using Microsoft Excel. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range) wherever appropriate. Categorical variables were expressed as a percentage. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test wherever appropriate. Continuous variables were compared using the Student’s t test or Mann-Whitney tests wherever appropriate. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Propensity matched analysis was performed in view of the significant difference in the number of patients in each arm. In the propensity score model, we included baseline demographic and clinical variables known to influence treatment selection, such as age, sex, previous surgery, and number of ERCP sessions. Post-treatment variables (e.g., number of ESWL sessions and CBD clearance outcomes) were excluded to avoid adjustment for factors influenced by the treatment itself. The quality of propensity score matching was assessed by comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between the LL and ESWL groups before and after matching. Covariate balance was evaluated using standardized mean differences (SMDs) in which an SMD of less than 0.1 was considered indicative of good balance and values below 0.2 were deemed acceptable. SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States) was used for statistical analysis.

A total of 6011 patients underwent ERCP for biliary stones between January 2019 and December 2022 of which 485 patients had difficult CBD stones. Twenty-seven patients were excluded due to various reasons (incomplete data, unwillingness/contradiction to undergo further procedures, directly opting/being advised for surgery). Finally, data for 458 patients were retrospectively analyzed of which 387 patients underwent ESWL while 71 were managed with LL followed by CBD clearance (Figure 1). The mean age of patients undergoing ESWL was 53.8 ± 15.7 years, and 58.7% of the patients were males. Thirty-five patients with Mirizzi syndrome were managed with ESWL. The mean age of patients undergoing LL was 55.0 ± 15.4 years, and 46 (64.8%) of the patients were males. Seven patients with Mirizzi syndrome underwent LL.

After propensity score matching 63 patients from each group were retained for analysis, and the distribution of baseline characteristics was well balanced across the two groups with all SMDs below 0.2, indicating adequate matching quality. Matching substantially improved covariate balance. Most variables [age (0.06), number of stones (0.09), number of ERCP sessions (0.09)] were well balanced (SMD < 0.1), but some variables [gender (0.3)] showed moderate imbalance. After matching most continuous variables [age (1.3) and number of ERCP sessions (0.78)] had ratios closer to 1 (good balance).

The two groups were compared for number of CBD stones and were found comparable (P = 0.3). Overall, 181 (46.8%) patients had a single CBD stone, 13 (3.4%) patients had two CBD stones, and 193 (49.8%) patients had more than two stones in the ESWL arm. Similarly in the LL arm, 36 (50.7%) patients had a single CBD stone, 4 (5.6%) had two CBD stones, and 31 (43.7%) patients had more than two CBD stones (Table 1).

| ESWL group (n = 387) | LL group (n = 71) | P value | |

| Mean age, years | 53.8 ± 15.7 | 55.0 ± 15.4 | 0.49 |

| Males/females, % | 58.7/41.3 | 64.8/35.2 | 0.20 |

| Number of CBD stones: 1/2/multiple, % | 46.8/3.4/49.8 | 50.7/5.6/43.6 | 0.30 |

| Mirrizzi syndrome | 35 (9.0) | 7 (9.9) | 0.40 |

In the ESWL arm complete CBD clearance was achieved in 368 (95.1%) patients with 68.7% of patients requiring 1-2 ESWL sessions. The mean number of ESWL sessions required for complete stone fragmentation was 2.1 ± 1.3. In the LL arm complete CBD clearance was achieved in 97.2% (n = 69) of patients. There was no significant difference in efficacy between ESWL and LL (95.1% vs 97.2%, respectively; P = 0.4; Table 2). Complete CBD clearance in a single session was achieved in 58 patients (81.7%); 18.3% of patients required 2-3 sessions for fragmented stone clearance. The mean number of LL sessions required for complete stone fragmentation was 1.4 ± 0.7.

| ESWL (n = 387) | LL (n = 71) | P value | |

| CBD clearance | 368 (95.0) | 69 (97.2) | 0.4 |

| Number of sessions of ESWL/LL | 2.1 ± 1.3 | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 0.2 |

| Number of ERCP sessions required | 2.1 ± 0.6 | 2.3 ± 0.7 | 0.9 |

There was no significant difference in the overall complication rate with ESWL and LL (P = 0.3). In the ESWL arm 3 patients had cholangitis while 4 patients had post-sphincterotomy bleed. Both were managed conservatively. Four patients (1%) had pancreatitis post-ERCP of whom 3 patients had mild (modified Atlanta classification) and 1 patient had moderately severe pancreatitis (modified Atlanta classification)[18]. In the LL arm 2 patients had cholangitis while 1 patient had mild pancreatitis, which was managed conservatively. Patients in whom complete CBD clearance was not achieved were referred for surgery (Table 3).

| Complications | ESWL (n = 387) | LL (n = 71) | P value |

| Overall | 11 (2.8) | 3(4.2) | 0.3 |

| Cholangitis | 3 (0.8) | 2 (2.8) | |

| Post-sphincterotomy bleed | 4 (1.0) | 0 | |

| Pancreatitis | 4 (1.0) | 1 (1.4) |

The clearance of difficult CBD stones cannot usually be obtained with standard techniques like sphincterotomy or large balloon dilatation. The management in such cases requires specialized procedures like ESWL, cholangioscopy-assisted lithotripsy, or mechanical lithotripsy. This is one of the first studies comparing the efficacy and safety of two different techniques of managing difficult CBD stones: ESWL using the latest lithotripter and LL. We found that ESWL using the latest lithotripter device was able to achieve a similar rate of CBD clearance compared with single operator cholangioscope and LL. The average number of ERCP sessions required for complete CBD clearance were similar among the ESWL and LL arms. There was no difference in overall complication rate between the two groups.

Mechanical lithotripsy has historically been the cornerstone in the treatment of difficult bile duct stones[19,20]. Mechanical lithotripsy has been reported to have a success rate ranging from 80%-90% although the success rate at the first attempt is only about 50%-70%[19,21,22]. Despite its high success rate mechanical lithotripsy often required multiple attempts or procedures with a high rate of failure in cases of very large stones, stones in difficult anatomical locations, or impacted stones. Furthermore, it was associated with complications such as basket impaction, bile duct injury, and incomplete stone fragmentation[23]. The advent of newer techniques like ESWL and LL offered less invasive, more effective alternatives with higher success rates and fewer complications. However, mechanical lithotripsy remains an important tool, particularly in settings in which these newer technologies are not available.

Our study findings align with and add to the growing body of literature on the efficacy and safety of ESWL and LL in managing difficult CBD stones. Several studies have shown that ESWL can achieve bile duct clearance rates of 80%-90% with older-generation lithotripters[6,7,14,24]. In comparison, our study achieved a clearance rate of 95.1% using the latest Dornier Delta III lithotripter, demonstrating the potential improvements offered by this newer technology. LL has also been reported to have clearance rates between 88% and 95%, consistent with the 97.2% rate observed in our study. Importantly, our findings suggest no significant difference in overall efficacy between ESWL and LL (95.1% vs 97.2%, P = 0.4), highlighting both as effective options for stone clearance.

Additionally, complication rates such as cholangitis and post-ERCP pancreatitis in our study were within the range reported in previous studies, further supporting the safety profile of these interventions. In a systematic review of 32 studies with 1969 patients, the complication rate of ESWL (8.4%) and LL (9.6%) was found to be comparable while it was significantly higher for patients treated with electrohydraulic lithotripsy (13.8%; P = 0.04)[17].

Despite the large cohort size and robust data collection, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, this was a single-center, retrospective study, potentially limiting the generalizability of the results to other populations or clinical settings. Additionally, the lack of randomization could introduce selection bias as patients were allocated to ESWL or LL based on clinical discretion rather than a standardized protocol. Moreover, follow-up data were limited, and long-term outcomes such as stone recurrence or the need for repeat procedures were not evaluated. Another limitation was that this study did not directly assess patient-reported outcomes such as pain or quality of life after the procedures. This data would have provided valuable insights into the overall patient experience. Lastly, the availability and cost of advanced technologies like the Dornier Delta III lithotripter or single operator cholangioscope-based LL may limit the widespread application of these findings in resource-limited settings.

This study demonstrated that both ESWL using the latest Dornier Delta III lithotripter and LL are highly effective and safe methods for managing difficult bile duct stones. With similar rates of stone clearance and complication profiles, both techniques represent valuable options in the endoscopic management of complex biliary stone disease. However, the choice of technique should be individualized, taking into account the availability of expertise and equipment at the center and individualized cost analysis. The results of this study suggest that the latest ESWL technology has narrowed the efficacy gap between traditional shock wave lithotripsy and LL. Future research would benefit from larger, multicenter randomized trials to further confirm these findings and assess long-term outcomes as well as to evaluate patient-centered outcomes such as quality of life and cost-effectiveness of these procedures.

| 1. | Figueiredo JC, Haiman C, Porcel J, Buxbaum J, Stram D, Tambe N, Cozen W, Wilkens L, Le Marchand L, Setiawan VW. Sex and ethnic/racial-specific risk factors for gallbladder disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17:153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Shaffer EA. Gallstone disease: Epidemiology of gallbladder stone disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:981-996. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 444] [Cited by in RCA: 507] [Article Influence: 25.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 3. | Stinton LM, Shaffer EA. Epidemiology of gallbladder disease: cholelithiasis and cancer. Gut Liver. 2012;6:172-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 556] [Cited by in RCA: 782] [Article Influence: 55.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lauri A, Horton RC, Davidson BR, Burroughs AK, Dooley JS. Endoscopic extraction of bile duct stones: management related to stone size. Gut. 1993;34:1718-1721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Trikudanathan G, Navaneethan U, Parsi MA. Endoscopic management of difficult common bile duct stones. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:165-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Troncone E, Mossa M, De Vico P, Monteleone G, Del Vecchio Blanco G. Difficult Biliary Stones: A Comprehensive Review of New and Old Lithotripsy Techniques. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022;58:120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Neuhaus H, Zillinger C, Born P, Ott R, Allescher H, Rösch T, Classen M. Randomized study of intracorporeal laser lithotripsy versus extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy for difficult bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:327-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lee JH. Is combination biliary sphincterotomy and balloon dilation a better option than either alone in endoscopic removal of large bile-duct stones? Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:727-729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Binmoeller KF, Brückner M, Thonke F, Soehendra N. Treatment of difficult bile duct stones using mechanical, electrohydraulic and extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. Endoscopy. 1993;25:201-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | McHenry L, Lehman G. Difficult bile duct stones. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2006;9:123-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Korrapati P, Ciolino J, Wani S, Shah J, Watson R, Muthusamy VR, Klapman J, Komanduri S. The efficacy of peroral cholangioscopy for difficult bile duct stones and indeterminate strictures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endosc Int Open. 2016;4:E263-E275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Maydeo A, Kwek BE, Bhandari S, Bapat M, Dhir V. Single-operator cholangioscopy-guided laser lithotripsy in patients with difficult biliary and pancreatic ductal stones (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1308-1314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cecinato P, Fuccio L, Azzaroli F, Lisotti A, Correale L, Hassan C, Buonfiglioli F, Cariani G, Mazzella G, Bazzoli F, Muratori R. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy for difficult common bile duct stones: a comparison between 2 different lithotripters in a large cohort of patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:402-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ellis RD, Jenkins AP, Thompson RP, Ede RJ. Clearance of refractory bile duct stones with extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy. Gut. 2000;47:728-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Muratori R, Azzaroli F, Buonfiglioli F, Alessandrelli F, Cecinato P, Mazzella G, Roda E. ESWL for difficult bile duct stones: a 15-year single centre experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4159-4163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Adamek HE, Maier M, Jakobs R, Wessbecher FR, Neuhauser T, Riemann JF. Management of retained bile duct stones: a prospective open trial comparing extracorporeal and intracorporeal lithotripsy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:40-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Veld JV, van Huijgevoort NCM, Boermeester MA, Besselink MG, van Delden OM, Fockens P, van Hooft JE. A systematic review of advanced endoscopy-assisted lithotripsy for retained biliary tract stones: laser, electrohydraulic or extracorporeal shock wave. Endoscopy. 2018;50:896-909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zhao K, Adam SZ, Keswani RN, Horowitz JM, Miller FH. Acute Pancreatitis: Revised Atlanta Classification and the Role of Cross-Sectional Imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;205:W32-W41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Garg PK, Tandon RK, Ahuja V, Makharia GK, Batra Y. Predictors of unsuccessful mechanical lithotripsy and endoscopic clearance of large bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:601-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Riemann JF, Seuberth K, Demling L. Mechanical lithotripsy of common bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 1985;31:207-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sorbi D, Van Os EC, Aberger FJ, Derfus GA, Erickson R, Meier P, Nelson D, Nelson P, Shaw M, Gostout CJ. Clinical application of a new disposable lithotripter: a prospective multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:210-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Leung JW, Tu R. Mechanical lithotripsy for large bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:688-690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Thomas M, Howell DA, Carr-Locke D, Mel Wilcox C, Chak A, Raijman I, Watkins JL, Schmalz MJ, Geenen JE, Catalano MF. Mechanical lithotripsy of pancreatic and biliary stones: complications and available treatment options collected from expert centers. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1896-1902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Angsuwatcharakon P, Rerknimitr R. Cracking Difficult Biliary Stones. Clin Endosc. 2021;54:660-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/