Published online Feb 27, 2026. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v18.i2.111962

Revised: August 1, 2025

Accepted: December 18, 2025

Published online: February 27, 2026

Processing time: 212 Days and 14.5 Hours

Non-invasive clinical scores are widely used to detect hepatic steatosis and steatohepatitis, but their accuracy in individuals with obesity is limited. Most of these tools were developed for non-obese populations and do not account for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) spectrum. Moreover, the potential modifying effect of metabolic syndrome (MetS) on the diagnostic performance of these scores remains unclear. Given the global burden of obesity and MASLD, there is a pressing need to refine diagnostic strategies for early detection. We hypothesized that diagnostic performance may vary by MetS status and can be improved with adjusted thresholds.

To evaluate and optimize three clinical scores for steatosis and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), including assessment by MetS status.

This cross-sectional study included 95 individuals undergoing bariatric surgery at a hospital in Brazil. Clinical scores [non-alcoholic fatty liver disease liver fat score (NLFS), hepatic steatosis index (HSI), and fatty liver index (FLI)] were calculated from preoperative data. Liver biopsy was used as the reference standard to assess steatosis and MASH. Diagnostic accuracy was evaluated using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, and optimal cut-offs were determined by Youden’s index. Logistic regression with interaction terms assessed whether MetS modified the diagnostic performance of each score across histological outcomes.

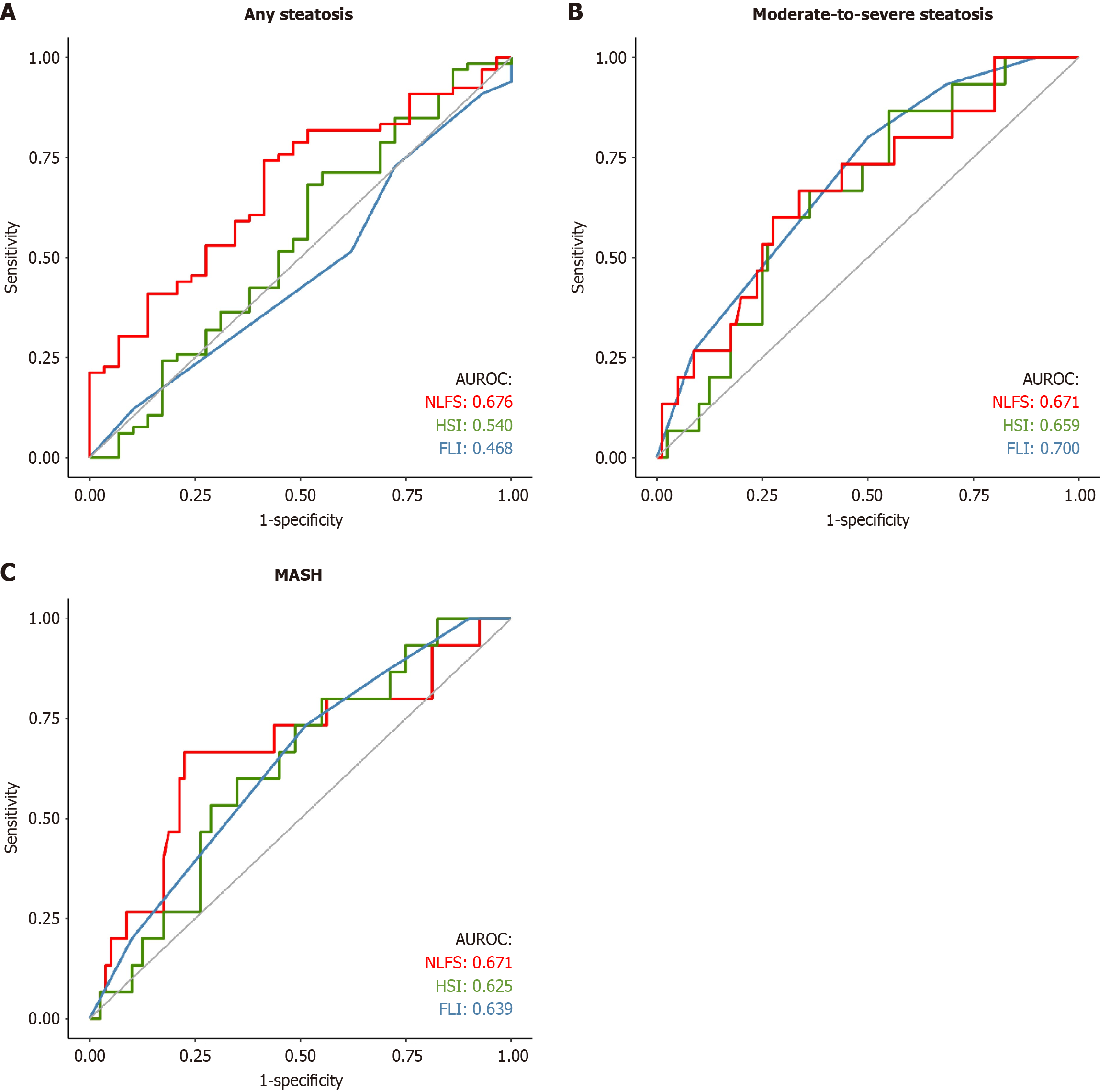

Sixty-six individuals (69.5%) had steatosis, and fifteen (15.8%) had moderate-to-severe steatosis and MASH. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curves for any steatosis was 0.676 (NLFS), 0.540 (HSI), and 0.468 (FLI); for moderate-to-severe steatosis, 0.671 (NLFS), 0.659 (HSI), and 0.700 (FLI); and for MASH, 0.671 (NLFS), 0.625 (HSI), and 0.639 (FLI). Standard cut-offs performed poorly; optimized thresholds improved both sensitivity and specificity. NLFS outperformed FLI for any steatosis (P = 0.021). No significant interactions were found between MetS and any score (all P > 0.05), indicating that diagnostic accuracy did not significantly differ by MetS status.

NLFS, HSI, and FLI show limited accuracy in obese individuals. Adjusting thresholds improves performance. Diagnostic utility remains consistent regardless of MetS, supporting their use across the MASLD spectrum.

Core Tip: This study evaluated and optimized the diagnostic performance of three clinical scores - non-alcoholic fatty liver disease liver fat score, Hepatic Steatosis Index, and Fatty Liver Index - for detecting steatosis and steatohepatitis in obese individuals with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Using liver biopsy as a reference, we showed that standard thresholds performed poorly, but accuracy improved with optimized cut-offs. Metabolic syndrome status did not affect score performance significantly, suggesting that these tools can be applied across the metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease metabolic spectrum. Our findings provide practical insights into improving non-invasive diagnosis in high-risk populations, where early detection is essential but challenging.

- Citation: Farina GS, Brambilla B, Pandolfo EM, Lazzaretti LKN, Kuiava SMS, Graciolli AM, Kriger VM, Fistarol CHDB, Sgarioni AC, Giovanardi HP, Tregnago AC, Riva F, Scholze CDS, Agostini DC, Dellamea B, Tamayo A, Cerqueira TL, Soldera J, Illigens BMW. Performance of three clinical scores for steatosis and steatohepatitis and their interaction with metabolic syndrome in obese individuals. World J Hepatol 2026; 18(2): 111962

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v18/i2/111962.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v18.i2.111962

Obesity affects 42.4% of the United States population. It is closely linked to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), formerly known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), with global prevalence estimates between 9% and 40%[1-5]. MASLD is often underdiagnosed, increasing morbidity, mortality, and healthcare burden. Therefore, early detection is essential for better outcomes. Both obesity and MASLD are major public health concerns[6-10], associated with metabolic syndrome (MetS), type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), hypertension, and dyslipidemia[11-15]; cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death in MASLD[16-19]. MASLD spans from benign steatosis to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), which may progress to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma[20]. Fibrosis is a key prognostic marker[20,21], and up to 25% of patients may develop advanced disease, often silently[21-23]. Fortunately, the early stages are reversible[1].

Liver biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosing hepatic steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis. However, its invasive nature, high cost, and sampling variability limit its routine use[17,24-27]. Consequently, non-invasive techniques have emerged as alternatives. These include clinical scoring systems and imaging-based methods[28,29]. Among the most commonly used clinical scores are the NAFLD liver fat score (NLFS), hepatic steatosis index (HSI), and fatty liver index (FLI)[5,30]. While a few non-invasive scores exist for diagnosing MASH, many are costly, patented, and not widely implemented in clinical practice[31,32]. By contrast, clinical scores are accessible, affordable, and readily available through online calculators[30,33,34]. Despite these advantages, clinical scores were primarily developed in non-obese populations, and no new tools have been designed to align with MASLD’s updated diagnostic criteria. Imaging-based non-invasive techniques - particularly ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging - have shown progress but remain limited by availability and cost, especially in resource-constrained settings[28,35-37].

In individuals with obesity, these scores often perform poorly using general-population cut-offs[24,38-40], and optimal thresholds for detecting steatosis or MASH remain undefined. Additionally, MASLD now includes patients with me

This study was a cross-sectional analysis of the baseline data from a larger, ongoing cohort study, namely the MetS and MASLD in bariatric patients study conducted at the University of Caxias do Sul (UCS) and the Caxias do Sul General Hospital, Brazil, from October 2019 to April 2023. Patients eligible for bariatric surgery were included if they were adults (≥ 18 years) with obesity class III (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2) or class II (BMI 35-39.99 kg/m2) with at least one obesity-related comorbidity (hypertension, hyperlipidemia, T2DM, or obstructive sleep apnea) and refractory to medical treatment. Exclusion criteria included non-MASLD liver diseases, excessive alcohol intake (> 30 g/day for men, > 20 g/day for women), and non-Roux-en-Y gastric bypass procedures. MASLD and MASH terminology followed updated guidelines. The UCS Ethics Committee approved the study protocol (Protocol No. CAAE 11412219.0.0000.5341), and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants were volunteers and provided written in

All participants included in the study were allocated to a single group. Clinical and biochemical data were collected from the medical records. Biomarker scores for detecting MASLD were calculated using clinical and biochemical data. At the time of surgery, a liver biopsy was performed.

Clinical data were collected on the day of the surgery and included age, sex, height, weight, BMI, waist circumference (WC), T2DM, hypertension, smoking, and dyslipidemia. Biochemical data encompassed aspartate transaminase, alanine transaminase, gamma-glutamyl transferase, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose, glycated hemoglobin, fasting insulin, and platelet count. MetS diagnosis followed the criteria by the American Heart Association[42] as having at least three of the five following conditions: (1) Central/abdominal obesity measured by WC (> 102 cm for men and > 88 cm for women); (2) Triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL or use of medication for treating high triglycerides; (3) HDL cholesterol < 40 mg/dL for men and < 50 mg/dL for women or use of medication for treating low HDL cholesterol; (4) Blood pressure ≥ 135/80 mmHg or use of medication for treating high blood pressure; and (5) Fasting glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL or use of medication for treating high blood glucose.

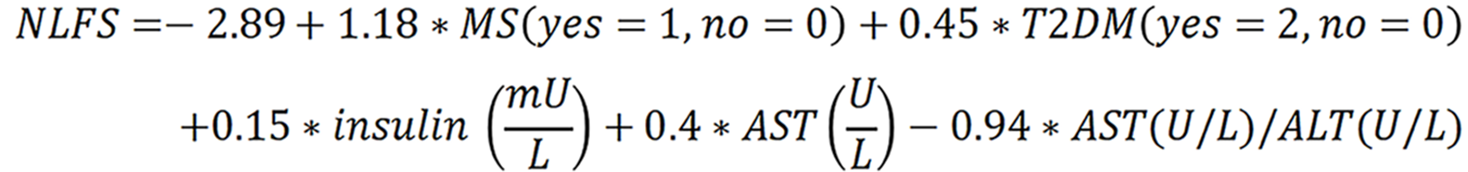

We selected three commonly used and widely validated clinical scores[30] as biomarkers to detect MASLD: NLFS, HSI, and FLI. The NLFS was calculated as:

NLFS > -0.64 indicates having any degree of steatosis. Values > 0.16 predict moderate-to-severe steatosis[43].

HSI was calculated as:

HSI ≥ 36 highly suggests the presence of MASLD[44].

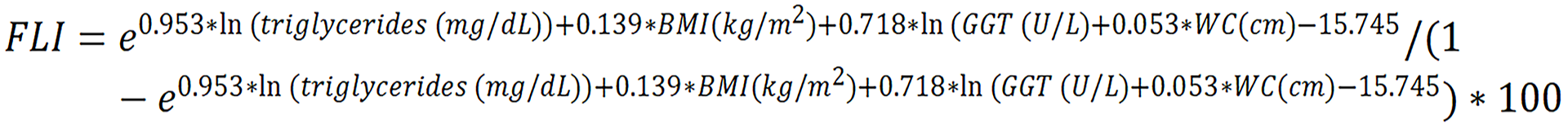

FLI was calculated as:

FLI ranges from 0 to 100, while values ≥ 60 indicate a high risk of fatty liver[45]. For convenience, we used freely available online calculators (MDApp and MDCalc) to compute these scores based on their original published formulas. These platforms serve only as user-friendly interfaces and do not modify the calculation algorithms; the formulas used are identical to those validated in the original scientific publications.

Liver biopsy was performed using a wedge technique during bariatric surgery. The tissue fragments were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for 18-24 hours, and then embedded in paraffin. Stains were carried out using 3-μm-thick sections obtained from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue. Hematoxylin and eosin, Masson’s trichrome, Picrosirius red, and Perls’ Prussian blue staining were performed. The NAFLD activity score (NAS) was calculated by assessing steatosis (0-3), lobular inflammation (0-3), and hepatocyte ballooning (0-2). Steatosis was classified as absent (S0, < 5% parenchymal involvement), mild (S1, 5%-33%), moderate (S2, 34%-66%), or severe (S3, > 66%). Liver fibrosis was staged on a scale from 0 to 4: Stage 0 (absent); stage 1 (perisinusoidal or periportal fibrosis); stage 2 (perisinusoidal and periportal/portal fibrosis); stage 3 (bridging fibrosis); and stage 4 (cirrhosis). MASLD was defined as histologically confirmed steatosis with at least one MetS criterion (according to the American Heart Association’s criteria). MASH was diagnosed based on NAS ≥ 5 regardless of fibrosis or NAS ≥ 4 with hepatic fibrosis, in the presence of at least one MetS criterion[46]. Histopathological evaluation was performed independently by two pathologists. A third experienced pathologist reviewed all findings and resolved any discrepancies. All pathologists were blinded to the participants’ clinical and laboratory data.

Statistical analyses compared the three clinical scores to liver biopsy for any steatosis, moderate-to-severe steatosis, and MASH. Categorical variables are reported as n (%), while continuous variables are summarized as median and interquartile range or mean ± SD. Missing data were imputed using the Expectation-Maximization algorithm, and analyses were conducted on the imputed dataset. Normality was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test and histogram visualization. Group comparisons used the Mann-Whitney U test or Welch’s t-test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical and ordinal variables.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated, and area under the ROC curve (AUROC) were calculated with 95% confidence intervals, categorized as excellent (≥ 0.900), good (0.800-0.899), fair (0.700-0.799), poor (0.600-0.699), random (0.500-0.599), or worse-than-random (< 0.500). Youden’s index determined optimal cut-offs. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), positive likelihood ratio (+LR), and negative LR (-LR) were calculated for standard and optimized cut-offs. Pairwise AUROC comparisons were performed using DeLong’s test with Hochberg adjustment. Venn diagrams were generated to illustrate the overlap in positive classifications across the three clinical scores, and are presented in the Supplementary material.

To evaluate whether the presence of MetS modified the diagnostic association between each score and histological assessment, logistic regression models were fitted, including an interaction term between each score and MetS status. The models were created for any steatosis, moderate-to-severe steatosis, and MASH as individual binary outcomes. Odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals, and P values were reported for the main effects and interaction terms. A two-tailed alpha of 0.05 was used. Analyses were conducted in R v4.3.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and used the pROC, epiR, ggplot2, misty, and mix packages for R.

A total of 105 individuals with class II or higher obesity undergoing preoperative bariatric surgery evaluation were included. Two withdrew from surgery (and the study), three withdrew from the study, three did not undergo liver biopsy, one had a surgical technique change due to clinical reasons, and one had missing biochemistry data. Thus, 95 individuals were analyzed. Missing data across all the variables varied between 0% and 12.6%. Clinical and laboratory information were present to calculate NLFS for 83 participants (12.6% of missing data), HSI for all 95 participants, and FLI for 94 (1% of missing data). Little’s Missing Completely At Random test resulted in P = 0.832, suggesting the data are missing completely at random. Statistical analysis was performed on an imputed dataset (all scores had 95 cases) after the imputation process.

Baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The median BMI was 42.9 kg/m2 (interquartile range: 40.7-45.4), and the mean age was 43 years (SD: 9.2). The majority were female (84.2%). Histopathological evaluation identified 66 individuals (69.5%) with steatosis, 15 (15.8%) with moderate-to-severe steatosis, and 15 (15.8%) with MASH. T2DM and glucose levels were associated with steatosis and MASH, while higher aspartate transaminase, alanine transaminase, gamma-glutamyl transferase, and glycated hemoglobin levels were linked to moderate-to-severe steatosis and MASH. The prevalence of MetS did not differ between groups.

| Characteristic | Total | Any steatosis1 | Moderate-to-severe steatosis1 | MASH1 | ||||||

| Presence | Absence | P value | Presence | Absence | P value | Presence | Absence | P value | ||

| Age (year), mean ± SD | 43 ± 9.2 | 44.6 ± 8.6 | 39.4 ± 9.6 | 0.016a | 45.9 ± 9.1 | 42.4 ± 9.2 | 0.197 | 45.8 ± 8.9 | 42.4 ± 9.2 | 0.196 |

| Female sex | 80 (84.2) | 58 (87.9) | 22 (75.9) | 0.220 | 12 (23.5) | 68 (85) | 0.700 | 12 (23.5) | 68 (85) | 0.700 |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 42.9 (40.7-45.4) | 42.6 (41-45) | 43.7 (40.5-45.5) | 0.465 | 43 (41.9-45.2) | 42.8 (40.3-45.4) | 0.524 | 43 (41.5-44.4) | 42.8 (40.3-45.4) | 0.858 |

| Obesity I | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.4) | 0.408 | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | 1.000 | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | 1.000 |

| Obesity II | 17 (17.9) | 12 (31.8) | 5 (17.2) | 2 (13.3) | 15 (18.75) | 2 (13.3) | 15 (18.75) | |||

| Obesity III | 77 (81) | 54 (81.8) | 23 (79.3) | 13 (86.7) | 64 (80) | 13 (86.7) | 64 (80) | |||

| WC (cm), median (IQR) | 126.6 (122.2-132.8) | 127 (123.5-132.4) | 124.7 (119.4-134.9) | 0.460 | 131.3 (122-138) | 126.2 (122.3-132.4) | 0.504 | 129.4 (125.3-136.8) | 125.9 (122.1-132.7) | 0.277 |

| Smoking | 13 (13.7) | 10 (15.2) | 3 (10.3) | 0.748 | 3 (20) | 10 (12.5) | 0.426 | 2 (13.3) | 11 (13.8) | 1.000 |

| T2DM | 27 (28.4) | 23 (34.8) | 4 (13.8) | 0.048a | 8 (53.3) | 19 (23.8) | 0.029a | 8 (53.3) | 19 (23.8) | 0.029a |

| Hypertension | 52 (54.7) | 39 (59.1) | 13 (44.8) | 0.264 | 10 (66.7) | 42 (52.5) | 0.401 | 7 (46.7) | 45 (56.2) | 0.577 |

| Dyslipidemia | 28 (29.5) | 21 (31.8) | 7 (24.1) | 0.626 | 9 (60) | 19 (23.8) | 0.011a | 9 (60) | 19 (23.8) | 0.011a |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 16 (16.8) | 11 (16.7) | 5 (17.2) | 1.000 | 3 (20) | 13 (16.3) | 0.713 | 3 (20) | 13 (16.3) | 0.713 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 65 (68.4) | 47 (71.2) | 18 (62.1) | 0.473 | 13 (86.7) | 52 (65) | 0.133 | 11 (73.3) | 54 (67.5) | 0.769 |

| AST (U/L), median (IQR) | 19 (15-24.5) | 18.5 (15-24) | 19 (8-17) | 0.267 | 23 (16-31.5) | 18 (15-23.2) | 0.066 | 22 (17-31.5) | 18 (15-24) | 0.028a |

| Elevated AST2 | 6 (6.3) | 4 (6.1) | 2 (6.9) | 1.000 | 3 (20) | 3 (3.8) | 0.048a | 3 (20) | 3 (3.8) | 0.048a |

| ALT (U/L), median (IQR) | 20 (16-30.5) | 20.5 (15-31) | 19 (18-27) | 0.633 | 29 (19.5-52) | 19 (15-27.25) | 0.013a | 29 (20-52) | 19 (15-27.25) | 0.010a |

| Elevated ALT3 | 20 (21) | 14 (21.2) | 6 (20.7) | 1.000 | 7 (46.7) | 13 (16.2) | 0.021a | 7 (46.7) | 13 (16.2) | 0.021a |

| GGT (U/L), median (IQR) | 33 (23.5-44.5) | 33 (25.2-44.8) | 32 (21-40) | 0.421 | 54 (31-90.5) | 32 (23-40) | 0.009a | 35 (31-90.5) | 32 (23-43) | 0.049a |

| Elevated GGT4 | 33 (34.7) | 23 (34.8) | 10 (34.5) | 1.000 | 9 (60) | 24 (30) | 0.038a | 7 (46.7) | 26 (32.5) | 0.377 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL), mean ± SD | 194.3 ± 36 | 192.3 ± 34 | 199.2 ± 40.6 | 0.445 | 182 ± 40.2 | 197.6 ± 34.9 | 0.206 | 188.3 ± 41.2 | 195.5 ± 35 | 0.534 |

| HDL (mg/dL), median (IQR) | 43 (39-50) | 43.5 (40–51.5) | 41 (38.5-49) | 0.431 | 42 (39.5-45.5) | 44 (39.2-52.5) | 0.480 | 42 (40-45.5) | 44 (39-51.8) | 0.442 |

| LDL (mg/dL), mean ± SD | 118.7 ± 33.2 | 116.5 ± 31.5 | 124 ± 37 | 0.357 | 102.5 ± 36 | 122.8 ± 31.9 | 0.068 | 110.2 ± 37 | 120.3 ± 32.4 | 0.334 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL), median (IQR) | 146.5 (110.2-182.2) | 148.5 (112.5-186) | 139.5 (108.5-170.5) | 0.565 | 176 (154-225) | 142 (107-175) | 0.043a | 164 (139-209) | 142 (104.5-177) | 0.066 |

| Platelet (count × 109/mm3), mean ± SD | 228 ± 60.6 | 278.8 ± 58.9 | 275.9 ± 65.9 | 0.847 | 256.2 ± 52.9 | 282.2 ± 61.5 | 0.117 | 248.2 ± 36.3 | 283.3 ± 62.7 | 0.009a |

| Glucose (mg/dL), median (IQR) | 99 (90-113) | 100 (91-120) | 97.6 (83.5-105.5) | 0.046a | 114 (100.5-153.5) | 98 (90-107) | 0.004a | 114 (99-163) | 98 (90-107) | 0.015a |

| HbA1c, median (IQR) | 5.7 (5.4-6.1) | 5.8 (5.4-6.2) | 5.5 (5.3-5.8) | 0.054 | 6 (5.8-7.6) | 5.6 (5.4-6) | 0.009a | 6.1 (5.7-7.1) | 5.6 (5.4-6.0) | 0.021a |

| Insulin (μUI/mL), median (IQR) | 19.3 (12-27.4) | 20.2 (13.8-27.4) | 14 (9.7-21.5) | 0.031a | 22.2 (15.7-28) | 17 (11.5-26.8) | 0.102 | 22.6 (15.1-28) | 19 (11.5-26.8) | 0.253 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL), median (IQR) | 0.8 (0.7-0.9) | 0.8 (0.7-0.8) | 0.8 (0.7-0.9) | 0.233 | 0.8 (0.7-0.8) | 0.8 (0.7-0.9) | 0.675 | 0.8 (0.7-0.8) | 0.8 (0.7-0.9) | 0.955 |

| HOMA-IR, median (IQR) | 4.5 (2.8-7.6) | 5.4 (3.5-8) | 2.8 (2.3-5.6) | 0.008a | 6.5 (5.3-8.5) | 4.2 (2.6-7.5) | 0.013a | 6.6 (4-9.7) | 4.4 (2.7-7.5) | 0.054 |

| Urea (mg/dL), median (IQR) | 29 (24-35) | 30 (25-36) | 27 (24-31) | 0.134 | 27 (22.5-32) | 29 (25-35) | 0.415 | 30 (23.5-35) | 29 (24-35) | 0.924 |

| Albumin (g/dL), mean ± SD | 4.2 ± 0.3 | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 4.3 ± 0.3 | 0.039a | 4.3 ± 0.3 | 4.2 ± 0.3 | 0.108 | 4.3 ± 0.2 | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 0.402 |

| NAS Score, median (IQR) | 1 (0-3) | 3 (1-4) | 0 (0-0) | < 0.001a | 6 (4.5-7) | 1 (0-2) | < 0.001a | 6 (5-7) | 1 (0-2) | < 0.001a |

| Steatosis on biopsy | 66 (69.5) | 66 (100) | 0 (0) | < 0.001a | 15 (100) | 51 (63.8) | 0.004a | 15 (100) | 51 (63.8) | 0.004a |

| Moderate/severe steatosis | 15 (15.8) | 15 (22.7) | 0 (0) | 0.004a | 15 (100) | 0 (0) | < 0.001a | 11 (73.3) | 4 (5) | < 0.001a |

| NASH on biopsy | 15 (15.8) | 15 (22.7) | 0 (0) | 0.004a | 11 (73.3) | 4 (5) | < 0.001a | 15 (100) | 0 (0) | < 0.001a |

| Fibrosis on biopsy | 10 (10.5) | 8 (12.1) | 2 (6.9) | 0.718 | 6 (40) | 4 (5) | 0.001a | 8 (53.3) | 2 (2.5) | < 0.001a |

| Significant fibrosis | 3 (3.7) | 3 (4.5) | 0 (0) | 0.551 | 2 (13.3) | 1 (1.2) | 0.064 | 3 (20) | 0 (0) | 0.003a |

| Advanced fibrosis | 2 (2.1) | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 1.000 | 1 (6.7) | 1 (1.2) | 0.292 | 2 (13.3) | 0 (0) | 0.024a |

| NLFS, median (IQR) | 1.07 (-0.53-2.72) | 1.47 (0.06-3.50) | -0.16 (-0.76-1.81) | 0.007a | 2.47 (0.88-4.31) | 0.89 (-0.55-2.44) | 0.036a | 2.70 (0.88-4.31) | 0.89 (-0.55-2.37) | 0.078 |

| Any steatosis | 75 (79) | 55 (83.3) | 20 (67) | 0.170 | 13 (86.7) | 62 (77.5) | 0.730 | 12 (80) | 63 (78.7) | 1.000 |

| Moderate/severe steatosis | 62 (65.3) | 49 (74.2) | 13 (44.8) | 0.009a | 12 (80) | 50 (62.5) | 0.246 | 12 (80) | 50 (62.5) | 0.359 |

| HSI, median (IQR) | 55.05 (51.43-57.99) | 55.10 (51.90-58.02) | 54.89 (50.08-57.91) | 0.542 | 57.2 (54.47-59.27) | 54.7 (50.92-57.37) | 0.052 | 57.1 (54.47-58.51) | 54.7 (51.21-57.95) | 0.127 |

| Presence of steatosis | 95 (100) | 66 (100) | 29 (100) | 1.000 | 15 (100) | 80 (100) | 1.000 | 15 (100) | 80 (100) | 1.000 |

| FLI, median (IQR) | 99 (97-99) | 99 (97-99) | 99 (97-99) | 0.607 | 99 (99-99.5) | 98.5 (97-99) | 0.010a | 99 (98.5-99) | 98 (97-99) | 0.074 |

| Presence of steatosis | 95 (100) | 66 (100) | 29 (100) | 1.000 | 15 (100) | 80 (100) | 1.000 | 15 (100) | 80 (100) | 1.000 |

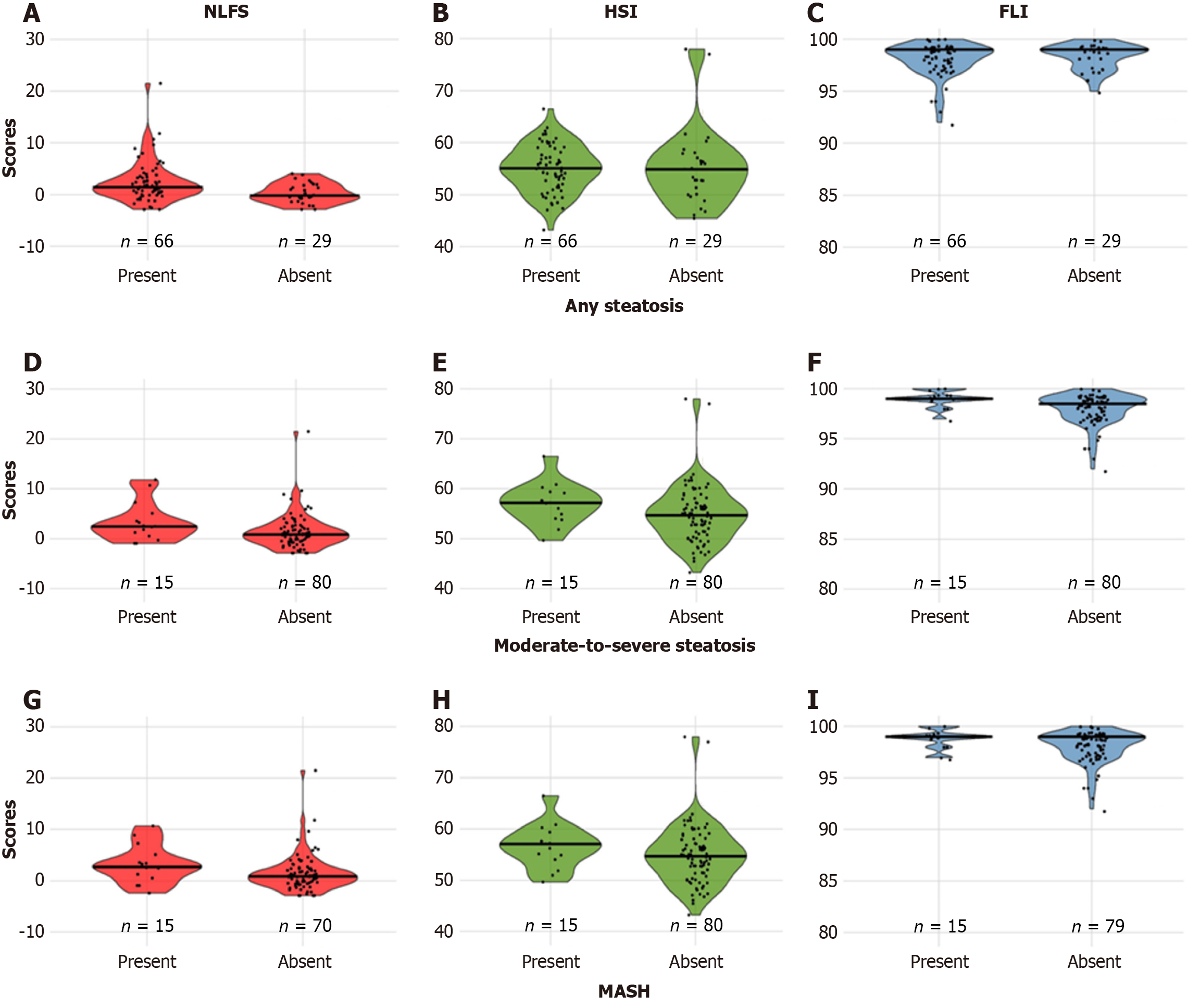

Using standard NLFS cut-offs, 79% of participants had any steatosis, and 65.3% had moderate-to-severe steatosis. HSI and FLI indicated a high risk for hepatic steatosis in all participants. NLFS values were significantly higher in those with any or moderate-to-severe steatosis. HSI values did not differ between groups, while FLI scores were significantly different only for moderate-to-severe steatosis. Score distributions for each condition are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1.

AUROCs for any steatosis were 0.676 for NLFS, 0.540 for HSI, and 0.468 for FLI (Figure 2). Using standard cut-offs, NLFS had 83% sensitivity, 31% specificity, 73% PPV, and 45% NPV. HSI and FLI both had 100% sensitivity but 0% specificity, with a PPV of 69% (NPV not calculable). Optimal cut-offs improved NLFS specificity to 59% while maintaining 74% sensitivity. HSI and FLI showed improved specificity (48% and 93%, respectively) at the cost of reduced sensitivity (Table 2).

| Score | AUROC (95%CI) | Cut-off | Se (95%CI)1 | Sp (95%CI)1 | PPV (95%CI)1 | NPV (95%CI)1 | +LR (95%CI) | -LR (95%CI) |

| Any steatosis | ||||||||

| NLFS | 0.676 (0.563-0.790) | -0.64 | 83% (72-91) | 31% (15-51) | 73% (62-83) | 45% (23-68) | 1.21 (0.93-1.58) | 0.54 (0.25-1.15) |

| 0.253 | 74% (62-84) | 59% (39-76) | 80% (68-89) | 50% (32-68) | 1.79 (1.14-2.83) | 0.44 (0.26-0.73) | ||

| HSI | 0.540 (0.406-0.674) | 36 | 100% (95-100) | 0% (0-12) | 69% (59-79) | NA (0-100) | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | NA (NA-NA) |

| 53.4 | 68% (56-79) | 48% (29-67) | 75% (62-85) | 40% (24-58) | 1.32 (0.89-1.94) | 0.66 (0.39-1.10) | ||

| FLI | 0.468 (0.348-0.588) | 60 | 100% (95-100) | 0% (0-12) | 69% (59-79) | NA (0-100) | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | NA (NA-NA) |

| 99.5 | 12% (5-22) | 93% (76-99) | 73% (39-94) | 31% (21-42) | 1.17 (0.33-4.10) | 0.98 (0.84-1.14) | ||

| Moderate-to-severe steatosis | ||||||||

| NLFS | 0.671 (0.542-0.822) | 0.16 | 80% (52-96) | 38% (27-49) | 19% (10-31) | 91% (76-98) | 1.28 (0.94-1.74) | 0.53 (0.19-1.53) |

| 1.83 | 67% (38-88) | 66% (55-76) | 27% (14-44) | 91% (81-97) | 1.98 (1.23-3.17) | 0.50 (0.24-1.05) | ||

| HSI | 0.659 (0.522-0.796) | 36 | 100% (78-100) | 0% (0-5) | 16% (9-25) | NA (0-0) | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | NA (NA-NA) |

| 57 | 60% (32-84) | 72% (61-82) | 29% (14-48) | 91% (81-96) | 2.18 (1.26-3.76) | 0.55 (0.29-1.04) | ||

| FLI | 0.700 (0.574-0.825) | 60 | 100% (78-100) | 0% (0-5) | 16% (9-25) | NA (0-100) | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | NA (NA-NA) |

| 98.5 | 80% (52-96) | 51% (39-62) | 23% (13-37) | 93% (81-99) | 1.60 (1.14-2.24) | 0.40 (0.14-1.13) | ||

| MASH | ||||||||

| NLFS | 0.671 (0.507-0.836) | -0.64 | 80% (52-96) | 21% (13-32) | 16% (9-26) | 85 (62-97) | 1.02 (0.77-1.34) | 0.94 (0.31-2.82) |

| 0.16 | 80% (52-96) | 38% (27-49) | 19% (10-31) | 91% (76-98) | 1.28 (0.94-1.74) | 0.53 (0.19-1.53) | ||

| 2.43 | 67% (38-88) | 78% (67-86) | 36% (19-56) | 93% (83-98) | 2.96 (1.72-5.09) | 0.43 (0.21-0.98) | ||

| HSI | 0.625 (0.482-0.768) | 36 | 100% (78-100) | 0% (0-5) | 16% (9-25) | NA (0-100) | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | NA (NA-NA) |

| 56.2 | 60% (32-84) | 65% (54-75) | 24% (12-41) | 90% (79-96) | 1.71 (1.03-2.85) | 0.62 (0.32-1.17) | ||

| FLI | 0.639 (0.502-0.776) | 60 | 100% (78-100) | 0% (0-5) | 16% (9-25) | NA (0-100) | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | NA (NA-NA) |

| 98.5 | 73% (45-92) | 49% (37-60) | 21% (11-35) | 91% (78-97) | 1.43 (0.99-2.08) | 0.55 (0.23-1.30) | ||

AUROCs were 0.671 for NLFS, 0.659 for HSI, and 0.700 for FLI (Figure 2). With standard cut-offs, NLFS had 80% sensitivity but low specificity (38%), while HSI and FLI had 100% sensitivity and 0% specificity. Optimal cut-offs improved the specificity for all scores, with NLFS reaching 66%, HSI 72%, and FLI 51%, while sensitivities remained above 60% (Table 2).

AUROCs were 0.671 for NLFS, 0.625 for HSI, and 0.639 for FLI (Figure 2). Standard cut-offs resulted in high sensitivity but low specificity, with NLFS achieving 80% sensitivity but only 21% specificity. Optimal cut-offs improved specificities to 78% for NLFS, 65% for HSI, and 49% for FLI, while maintaining reasonable sensitivities (Table 2).

NLFS and FLI differed significantly in assessing any steatosis (P = 0.021), while no significant differences were observed in other comparisons. Detailed comparisons for each histopathological condition are presented in Table 3.

No significant interactions were found between any score and MetS status for the prediction of steatosis or MASH (all P > 0.05), indicating that the diagnostic performance of the scores was not significantly different between patients with and without MetS. Table 4 shows the detailed results for each model.

| Score | Variable | OR | 95%CI | P value |

| Any steatosis | ||||

| NLFS | Score | 1.15 | 0.93-1.70 | 0.353 |

| MetS | 0.88 | 0.31-2.41 | 0.809 | |

| Score-MetS interaction | 1.24 | 0.78-1.85 | 0.295 | |

| HSI | Score | 0.99 | 0.09-1.20 | 0.896 |

| MetS | < 0.01 | < 0.01- > 100 | 0.904 | |

| Score-MetS interaction | 1.00 | 0.80-1.24 | 0.966 | |

| FLI | Score | 0.75 | 0.42 | 0.239 |

| MetS | < 0.01 | < 0.01- > 100 | 0.462 | |

| Score-MetS interaction | 1.29 | 0.67-2.66 | 0.452 | |

| Moderate-to-severe steatosis | ||||

| NLFS | Score | 0.93 | 0.40-1.22 | 0.780 |

| MetS | 1.85 | 0.38-13.63 | 0.479 | |

| Score-MetS interaction | 1.35 | 0.95-3.25 | 0.266 | |

| HSI | Score | 0.87 | 0.54-1.28 | 0.518 |

| MetS | < 0.01 | < 0.01- > 100 | 0.400 | |

| Score-MetS interaction | 1.22 | 0.82-2.00 | 0.354 | |

| FLI | Score | 1.63 | 0.66-10.99 | 0.471 |

| MetS | < 0.01 | < 0.01- > 100 | 0.718 | |

| Score-MetS interaction | 1.34 | 0.18-4.84 | 0.710 | |

| MASH | ||||

| NLFS | Score | 1.06 | 0.87-1.22 | 0.478 |

| MetS | 0.77 | 0.20-3.25 | 0.715 | |

| Score-MetS interaction | 1.14 | 0.90-1.48 | 0.279 | |

| HSI | Score | 0.93 | 0.069-1.20 | 0.584 |

| MetS | < 0.01 | < 0.01- > 100 | 0.329 | |

| Score-MetS interaction | 0.15 | 0.87-1.56 | 0.325 | |

| FLI | Score | 1.17 | 0.71-2.93 | 0.589 |

| MetS | < 0.01 | < 0.01- > 100 | 0.462 | |

| Score-MetS interaction | 1.45 | 0.48-3.84 | 0.463 | |

This study is the first, to our knowledge, to evaluate and recalibrate the NLFS, HSI, and FLI clinical scores within the MASLD framework in individuals with obesity - a high-risk yet underrepresented group. Unlike earlier studies centered on NAFLD, our analysis aligns with updated MASLD criteria and emphasizes the relevance of optimizing diagnostic tools for populations with prevalent metabolic dysfunction. Given the ongoing obesity epidemic and MASLD underdiagnosis, refining non-invasive tools in this context is vital[47,48].

The baseline characteristics of our cohort mirror those reported for bariatric surgery candidates[49-51]. We found biopsy-confirmed prevalences of 69.5% for any steatosis, 15.8% for moderate-to-severe steatosis, and 15.8% for MASH. While similar to overall MASLD prevalence, our study reported lower rates of moderate-to-severe steatosis and MASH than most studies[52,53]. Interestingly, only 13 individuals had both moderate-to-severe steatosis and MASH, suggesting heterogeneity in disease presentation. Discrepancies among NLFS, HSI, and FLI classification outcomes (Supplementary Figure 1) reinforce the lack of consensus when applying these tools to MASLD. In their original studies, NLFS, HSI, and FLI showed good diagnostic performance in general populations. However, they were not developed for obese individuals specifically, possibly limiting their accuracy. NLFS originally showed 86% sensitivity and 71% specificity (AUROC: 0.86), HSI showed 46% sensitivity and 92.4% specificity (AUROC: 0.812), and FLI showed 61% sensitivity and 86% specificity (AUROC: 0.84). In our study, initial evaluations using standard cut-offs showed that NLFS had high sensitivity but low specificity for any steatosis, moderate-to-severe steatosis, and MASH. Both HSI and FLI classified all cases as positive, yielding 100% sensitivity but 0% specificity, making NPV and -LR incalculable. Adjusting cut-offs using the Youden index improved the accuracy of all scores.

Diagnostic accuracy was better for moderate-to-severe steatosis and MASH than for any steatosis. NLFS showed consistently poor performance. HSI performed poorly for moderate-to-severe steatosis and MASH, and randomly for any steatosis. FLI’s results were variable and limited by a small number of unique values, flattening the ROC curves. Still, accuracy improved with optimized cut-offs: NLFS demonstrated the best sensitivity and specificity; FLI the worst. Similar AUROC values for MASLD detection in the general population were reported by Thomson et al[54].

For any steatosis, NLFS (cut-off of 0.253) had 74% sensitivity and 59% specificity, HSI (cut-off of 53.4) had 68% and 48%, and FLI (cut-off of 99.5) had 12% and 93%. PPV improved slightly with optimized cut-offs, while NPV remained low. Prior studies reported similar trends. Ooi et al[55] found high specificity (> 74%) but low sensitivity (< 25%), Byra et al[56] found HSI performed near chance (61.3% sensitivity, 58.9% specificity), and Garteiser et al[57] reported fair results for HSI and FLI (sensitivities: 78% and 77%; specificities: 59% and 62%). Across studies, PPV was consistently higher than NPV. Forouzesh et al[58] also found low sensitivity and specificity for HSI in MASLD detection in the general population.

For moderate-to-severe steatosis, NLFS (cut-off of 1.83) and HSI (cut-off of 57) had balanced sensitivity and specificity, while FLI (cut-off of 98.5) had high sensitivity but low specificity. PPV remained low (< 25%), whereas NPV was consistently high. Prior studies support these findings. Ooi et al[55] found poor NLFS performance and inconsistent results for HSI and FLI (sensitivities < 32%, specificities > 80%). Garteiser et al[57] found HSI and FLI performed worse in moderate-to-severe steatosis than in any steatosis (sensitivities: 86% and 77%; specificities: 49% and 50%). Coccia et al[59] reported fair performance in morbidly obese individuals (sensitivities: 69%-75%; specificity approximately 69% for NLFS and HSI, 60% for FLI). Parente et al[60] found initial thresholds for HSI and FLI had 100% sensitivity but 0% specificity, mirroring our findings. Optimized cut-offs improved HSI (≥ 53) to 71% sensitivity and 75% specificity, and FLI (≥ 96) to 85% sensitivity and 63% specificity, slightly higher than our results. Ooi et al[55] and Garteiser et al[57] reported balanced PPV and NPV, while Parente et al[60] found higher PPV for HSI and FLI in moderate-to-severe steatosis detection.

In MASH detection, NLFS outperformed the others in sensitivity and specificity. Even with optimized thresholds, PPVs were low and NPVs high. Francque et al[61] observed similar patterns, showing fair accuracy for NLFS (AUROC: 0.723) and poor accuracy for FLI (AUROC: 0.609). By contrast, clinical scores perform better in lean individuals. Otsubo et al[62] found FLI retained high sensitivity and specificity in normal BMI subgroups, suggesting obesity hampers score performance. Other studies have confirmed this finding[24,63-65]. Our MASLD findings align with prior NAFLD data. Despite all participants meeting MASLD criteria by obesity, one-third did not have MetS, allowing us to test interactions between MetS and score performance. None of the interactions were statistically significant, suggesting that score accuracy is not significantly modified by MetS status. This indicates potential applicability of these scores across MASLD’s metabolic spectrum.

Standard cut-offs performed poorly across the board, even after optimization[66,67]. This could be due to clinical and ethnic differences across validation cohorts[68]. These scores were developed in general populations and were influenced by obesity-related changes in serum biomarkers. BMI and WC - both integrated in HSI and FLI - may artificially inflate scores in obese individuals without corresponding hepatic damage[57,59]. Ethnicity also plays an important role, as NLFS was validated in Finns, HSI in Koreans, and FLI in Italians[43-45]. Ethnic differences in fat distribution and genetic predispositions affect MASLD risk and score accuracy[69-73]. Sociocultural and dietary patterns may further modulate these risks[71]. As such, clinical scores may underperform if not ethnically tailored to the ethnical characteristics of the population they were validated for. Variability also arises from differing reference standards. Original validations used imaging (magnetic resonance spectroscopy for NLFS; ultrasound for HSI and FLI), while more recent studies, including ours, used histology. This discrepancy may misclassify cases, skewing AUROC and diagnostic estimates.

No universal agreement exists on which score performs best. Some studies have favored FLI, especially in East Asians[33,74-77]; others have found HSI superior in Western populations[78]. Comparative studies in obese populations often favor NLFS[5,79,80]. Melania et al[81] found high concordance between NLFS and FLI. Lind et al[82] reported NLFS as optimal for high-risk groups and FLI for screening. Our findings support NLFS as the preferred tool for obese individuals. Since MASLD is usually asymptomatic until decompensated cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma takes place, early diagnosis is crucial[20,83-85]. Steatosis should not be overlooked, as early detection can prevent progression. While fibrosis is the main prognostic indicator, identifying steatosis early opens opportunities for intervention[5]. Clinical scores offer accessible, non-invasive diagnostic tools. However, fixed thresholds may not be suitable across all populations. Adjustments based on body composition and ethnicity are likely necessary[68,71]. Furthermore, their role in monitoring treatment or predicting outcomes remains unclear[86]. Future validation in multi-ethnic, longitudinal cohorts is essential.

Our study is among the first to test and optimize these scores in biopsy-confirmed patients with MASLD with obesity. Despite their NAFLD origins, our findings support their continued use in MASLD. Notably, their performance was unaffected by MetS status, suggesting utility across the MASLD spectrum. By recalibrating thresholds and confirming consistent performance in this population, we offer practical guidance for applying these tools, particularly in settings where liver biopsy or imaging is unavailable. Our findings may help reduce unnecessary invasive procedures while maintaining diagnostic rigor. Future work should focus on combining clinical scores with lab and imaging data, perhaps leveraging artificial intelligence-driven models to improve prediction. Multimodal, personalized tools incorporating metabolic, genetic, and demographic inputs may enhance accuracy, particularly in obese individuals. Collaborative, multi-ethnic, prospective studies are needed to refine these strategies.

Limitations include a small number of moderate-to-severe steatosis and MASH cases (n = 15), limiting statistical power for those subgroups. Although our total sample met power requirements, the distribution was imbalanced. Additionally, we lacked data on liver-specific medications, dietary patterns, and ethnicity, which may affect generalizability and performance. Being a single-center study may further limit broader application. Nonetheless, this study provides valuable insight into the recalibration and application of NLFS, HSI, and FLI in the MASLD landscape, offering clinicians evidence-based tools for improved non-invasive diagnosis in individuals with obesity.

In conclusion, standard thresholds of the clinical scores for detecting MASLD are inaccurate in individuals with obesity. Adjusting cut-offs improves classification accuracy and enhances diagnostic performance in this population. Among the scores assessed, NLFS appeared to be the most effective in predicting steatosis and MASH in obese individuals, with consistent performance across MetS subgroups. However, all scores require further validation in diverse MASLD populations to ensure broader applicability.

This work is part of Farina GS’s Master’s thesis in the Master’s Program in Clinical Research at Dresden International University, Dresden, Germany. The study itself - including its conceptualization, ethical approval, and data collection - was originally designed by the research team at the UCS and conducted entirely at the UCS and the Caxias do Sul General Hospital in Brazil. DIU later approved the use of this dataset for the completion of the author’s Master’s thesis, from which this manuscript is derived.

| 1. | Chaudhry A, Noor J, Batool S, Fatima G, Noor R. Advancements in Diagnostic and Therapeutic Interventions of Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Literature Review. Cureus. 2023;15:e44924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Boutari C, Mantzoros CS. A 2022 update on the epidemiology of obesity and a call to action: as its twin COVID-19 pandemic appears to be receding, the obesity and dysmetabolism pandemic continues to rage on. Metabolism. 2022;133:155217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 407] [Cited by in RCA: 678] [Article Influence: 169.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) Covariates 1980-2019 [Internet]. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) 2020. [cited 2024 Feb 19]. Available from: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/global-burden-disease-study-2019-gbd-2019-covariates-1980-2019. |

| 4. | Rinella ME, Lazarus JV, Ratziu V, Francque SM, Sanyal AJ, Kanwal F, Romero D, Abdelmalek MF, Anstee QM, Arab JP, Arrese M, Bataller R, Beuers U, Boursier J, Bugianesi E, Byrne CD, Castro Narro GE, Chowdhury A, Cortez-Pinto H, Cryer DR, Cusi K, El-Kassas M, Klein S, Eskridge W, Fan J, Gawrieh S, Guy CD, Harrison SA, Kim SU, Koot BG, Korenjak M, Kowdley KV, Lacaille F, Loomba R, Mitchell-Thain R, Morgan TR, Powell EE, Roden M, Romero-Gómez M, Silva M, Singh SP, Sookoian SC, Spearman CW, Tiniakos D, Valenti L, Vos MB, Wong VW, Xanthakos S, Yilmaz Y, Younossi Z, Hobbs A, Villota-Rivas M, Newsome PN; NAFLD Nomenclature consensus group. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Hepatology. 2023;78:1966-1986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1658] [Cited by in RCA: 1809] [Article Influence: 603.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ahn SB. Noninvasive serum biomarkers for liver steatosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Current and future developments. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2023;29:S150-S156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Prasad M, Sarin SK, Chauhan V. Expanding public health responses to non-communicable diseases: the NAFLD model of India. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8:969-970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wattacheril JJ, Abdelmalek MF, Lim JK, Sanyal AJ. AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Role of Noninvasive Biomarkers in the Evaluation and Management of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:1080-1088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 47.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chen J, Mao X, Deng M, Luo G. Validation of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) related steatosis indices in metabolic associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) and comparison of the diagnostic accuracy between NAFLD and MAFLD. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;35:394-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Portincasa P. NAFLD, MAFLD, and beyond: one or several acronyms for better comprehension and patient care. Intern Emerg Med. 2023;18:993-1006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Arias-Fernández M, Fresneda S, Abbate M, Torres-Carballo M, Huguet-Torres A, Sánchez-Rodríguez C, Bennasar-Veny M, Yañez AM, Busquets-Cortés C. Fatty Liver Disease in Patients with Prediabetes and Overweight or Obesity. Metabolites. 2023;13:531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jennison E, Byrne CD. Recent advances in NAFLD: current areas of contention. Fac Rev. 2023;12:10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Powell EE, Wong VW, Rinella M. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Lancet. 2021;397:2212-2224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 461] [Cited by in RCA: 1943] [Article Influence: 388.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (33)] |

| 13. | Lee H, Lee YH, Kim SU, Kim HC. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease and Incident Cardiovascular Disease Risk: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:2138-2147.e10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 309] [Cited by in RCA: 344] [Article Influence: 68.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 14. | Zhang S, Mak LY, Yuen MF, Seto WK. Screening strategy for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2023;29:S103-S122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Habibi J, DeMarco VG, Chen D, Whaley-Connell A, Hill MA, Jia G. Endothelial CD36 mediates diet-induced increases in aortic stiffness. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2025;205:52-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Duell PB, Welty FK, Miller M, Chait A, Hammond G, Ahmad Z, Cohen DE, Horton JD, Pressman GS, Toth PP; American Heart Association Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Hypertension; Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease; Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health; and Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Cardiovascular Risk: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2022;42:e168-e185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 453] [Article Influence: 113.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Zaman CF, Sultana J, Dey P, Dutta J, Mustarin S, Tamanna N, Roy A, Bhowmick N, Khanam M, Sultana S, Chowdhury S, Khanam F, Sakibuzzaman M, Dutta P. A Multidisciplinary Approach and Current Perspective of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2022;14:e29657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Heerkens L, van Kleef LA, de Knegt RJ, Voortman T, Geleijnse JM. Fatty Liver Index and mortality after myocardial infarction: A prospective analysis in the Alpha Omega Cohort. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0287467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lerchbaum E, Pilz S, Grammer TB, Boehm BO, Stojakovic T, Obermayer-Pietsch B, März W. The fatty liver index is associated with increased mortality in subjects referred to coronary angiography. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;23:1231-1238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Martinou E, Pericleous M, Stefanova I, Kaur V, Angelidi AM. Diagnostic Modalities of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: From Biochemical Biomarkers to Multi-Omics Non-Invasive Approaches. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12:407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Heyens LJM, Busschots D, Koek GH, Robaeys G, Francque S. Liver Fibrosis in Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: From Liver Biopsy to Non-invasive Biomarkers in Diagnosis and Treatment. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:615978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 28.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ismaiel A, Portincasa P, Dumitrascu DL. Natural History of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. In: Trifan A, Stanciu C, Muzica C, editors. Essentials of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Cham: Springer, 2023: 19-43. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Tsochatzis EA. Natural history of NAFLD: knowns and unknowns. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;19:151-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Reinshagen M, Kabisch S, Pfeiffer AFH, Spranger J. Liver Fat Scores for Noninvasive Diagnosis and Monitoring of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Epidemiological and Clinical Studies. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2023;11:1212-1227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Tun KM, Noureddin N, Noureddin M. Noninvasive tests in the evaluation of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A review. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2023;22:103-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yu JH, Lee HA, Kim SU. Noninvasive imaging biomarkers for liver fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: current and future. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2023;29:S136-S149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Younossi ZM, Loomba R, Anstee QM, Rinella ME, Bugianesi E, Marchesini G, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Serfaty L, Negro F, Caldwell SH, Ratziu V, Corey KE, Friedman SL, Abdelmalek MF, Harrison SA, Sanyal AJ, Lavine JE, Mathurin P, Charlton MR, Goodman ZD, Chalasani NP, Kowdley KV, George J, Lindor K. Diagnostic modalities for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, and associated fibrosis. Hepatology. 2018;68:349-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 335] [Article Influence: 41.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Nogami A, Yoneda M, Iwaki M, Kobayashi T, Honda Y, Ogawa Y, Imajo K, Saito S, Nakajima A. Non-invasive imaging biomarkers for liver steatosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: present and future. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2023;29:S123-S135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Neuman MG, Cohen LB, Nanau RM. Biomarkers in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28:607-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kechagias S, Ekstedt M, Simonsson C, Nasr P. Non-invasive diagnosis and staging of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Hormones (Athens). 2022;21:349-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Sanyal AJ, Shankar SS, Yates KP, Bolognese J, Daly E, Dehn CA, Neuschwander-Tetri B, Kowdley K, Vuppalanchi R, Behling C, Tonascia J, Samir A, Sirlin C, Sherlock SP, Fowler K, Heymann H, Kamphaus TN, Loomba R, Calle RA. Diagnostic performance of circulating biomarkers for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Nat Med. 2023;29:2656-2664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Harrison SA, Ratziu V, Boursier J, Francque S, Bedossa P, Majd Z, Cordonnier G, Sudrik FB, Darteil R, Liebe R, Magnanensi J, Hajji Y, Brozek J, Roudot A, Staels B, Hum DW, Megnien SJ, Hosmane S, Dam N, Chaumat P, Hanf R, Anstee QM, Sanyal AJ. A blood-based biomarker panel (NIS4) for non-invasive diagnosis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and liver fibrosis: a prospective derivation and global validation study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:970-985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 32.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Han S, Choi M, Lee B, Lee HW, Kang SH, Cho Y, Ahn SB, Song DS, Jun DW, Lee J, Yoo JJ. Accuracy of Noninvasive Scoring Systems in Assessing Liver Fibrosis in Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gut Liver. 2022;16:952-963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Ciardullo S, Vergani M, Perseghin G. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment. J Clin Med. 2023;12:5597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Frija G, Blažić I, Frush DP, Hierath M, Kawooya M, Donoso-Bach L, Brkljačić B. How to improve access to medical imaging in low- and middle-income countries ? EClinicalMedicine. 2021;38:101034. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 33.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Ozturk A, Olson MC, Samir AE, Venkatesh SK. Liver fibrosis assessment: MR and US elastography. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2022;47:3037-3050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Ozturk A, Grajo JR, Gee MS, Benjamin A, Zubajlo RE, Thomenius KE, Anthony BW, Samir AE, Dhyani M. Quantitative Hepatic Fat Quantification in Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Using Ultrasound-Based Techniques: A Review of Literature and Their Diagnostic Performance. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2018;44:2461-2475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Eren F, Kaya E, Yilmaz Y. Accuracy of Fibrosis-4 index and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease fibrosis scores in metabolic (dysfunction) associated fatty liver disease according to body mass index: failure in the prediction of advanced fibrosis in lean and morbidly obese individuals. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;34:98-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Drolz A, Wolter S, Wehmeyer MH, Piecha F, Horvatits T, Schulze Zur Wiesch J, Lohse AW, Mann O, Kluwe J. Performance of non-invasive fibrosis scores in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with and without morbid obesity. Int J Obes (Lond). 2021;45:2197-2204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Reinson T, Buchanan RM, Byrne CD. Noninvasive serum biomarkers for liver fibrosis in NAFLD: current and future. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2023;29:S157-S170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Segura-Azuara NLÁ, Varela-Chinchilla CD, Trinidad-Calderón PA. MAFLD/NAFLD Biopsy-Free Scoring Systems for Hepatic Steatosis, NASH, and Fibrosis Diagnosis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:774079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, Gordon DJ, Krauss RM, Savage PJ, Smith SC Jr, Spertus JA, Costa F; American Heart Association; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735-2752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7515] [Cited by in RCA: 8476] [Article Influence: 403.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Kotronen A, Peltonen M, Hakkarainen A, Sevastianova K, Bergholm R, Johansson LM, Lundbom N, Rissanen A, Ridderstråle M, Groop L, Orho-Melander M, Yki-Järvinen H. Prediction of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and liver fat using metabolic and genetic factors. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:865-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 490] [Cited by in RCA: 623] [Article Influence: 36.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Lee JH, Kim D, Kim HJ, Lee CH, Yang JI, Kim W, Kim YJ, Yoon JH, Cho SH, Sung MW, Lee HS. Hepatic steatosis index: a simple screening tool reflecting nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42:503-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1102] [Cited by in RCA: 1191] [Article Influence: 74.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Bedogni G, Bellentani S, Miglioli L, Masutti F, Passalacqua M, Castiglione A, Tiribelli C. The Fatty Liver Index: a simple and accurate predictor of hepatic steatosis in the general population. BMC Gastroenterol. 2006;6:33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1238] [Cited by in RCA: 2228] [Article Influence: 111.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Tavaglione F, Jamialahmadi O, De Vincentis A, Qadri S, Mowlaei ME, Mancina RM, Ciociola E, Carotti S, Perrone G, Bruni V, Gallo IF, Tuccinardi D, Bianco C, Prati D, Manfrini S, Pozzilli P, Picardi A, Caricato M, Yki-Järvinen H, Valenti L, Vespasiani-Gentilucci U, Romeo S. Development and Validation of a Score for Fibrotic Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21:1523-1532.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Cholongitas E, Chrysavgis L. Noninvasive diagnosis of hepatic steatosis in patients with severe obesity: a clinically challenging issue. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2023;133:16415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Ooi GJ, Mgaieth S, Eslick GD, Burton PR, Kemp WW, Roberts SK, Brown WA. Systematic review and meta-analysis: non-invasive detection of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease related fibrosis in the obese. Obes Rev. 2018;19:281-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Nunes BCM, de Moura DTH, Kum AST, de Oliveira GHP, Hirsch BS, Ribeiro IB, Gomes ILC, de Oliveira CPM, Mahmood S, Bernardo WM, de Moura EGH. Impact of Endoscopic Sleeve Gastroplasty in Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2023;33:2917-2926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Ayres ABS, Carneiro CRG, Gestic MA, Utrini MP, Chaim FDM, Callejas-Neto F, Chaim EA, Cazzo E. Identification of Predictors of Non-alcoholic Steatohepatitis and Its Severity in Individuals Undergoing Bariatric Surgery. Obes Surg. 2024;34:456-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Meneses D, Olveira A, Corripio R, Méndez MD, Romero M, Calvo-Viñuelas I, González-Pérez-de-Villar N, de-Cos-Blanco AI. The Benefit of Bariatric Surgery on Histological Features of Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease Assessed Through Noninvasive Methods. Obes Surg. 2022;32:2682-2695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Hagström H, Nasr P, Ekstedt M, Hammar U, Stål P, Hultcrantz R, Kechagias S. Risk for development of severe liver disease in lean patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A long-term follow-up study. Hepatol Commun. 2018;2:48-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 25.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Machado M, Marques-Vidal P, Cortez-Pinto H. Hepatic histology in obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery. J Hepatol. 2006;45:600-606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 384] [Cited by in RCA: 387] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Thomson ES, Oommen AT, S SV, Pillai G. Comparison of Non-invasive Liver Fat Scoring Systems as Markers of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Liver Disease. Cureus. 2024;16:e72222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Ooi GJ, Earnest A, Kemp WW, Burton PR, Laurie C, Majeed A, Johnson N, McLean C, Roberts SK, Brown WA. Evaluating feasibility and accuracy of non-invasive tests for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in severe and morbid obesity. Int J Obes (Lond). 2018;42:1900-1911. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Byra M, Szmigielski C, Kalinowski P, Paluszkiewicz R, Ziarkiewicz-Wróblewska B, Zieniewicz K, Styczyński G. Ultrasound- and biomarker-based assessment of hepatic steatosis in patients with severe obesity. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2023;133:16343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Garteiser P, Castera L, Coupaye M, Doblas S, Calabrese D, Dioguardi Burgio M, Ledoux S, Bedossa P, Esposito-Farèse M, Msika S, Van Beers BE, Jouët P. Prospective comparison of transient elastography, MRI and serum scores for grading steatosis and detecting non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in bariatric surgery candidates. JHEP Rep. 2021;3:100381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Forouzesh P, Kheirouri S, Alizadeh M. Predicting hepatic steatosis degree in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease using obesity and lipid-related indices. Sci Rep. 2025;15:8612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Coccia F, Testa M, Guarisco G, Bonci E, Di Cristofano C, Silecchia G, Leonetti F, Gastaldelli A, Capoccia D. Noninvasive assessment of hepatic steatosis and fibrosis in patients with severe obesity. Endocrine. 2020;67:569-578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Parente DB, Perazzo H, Paiva FF, Campos CFF, Saboya CJ, Pereira SE, Silva FDE, Rodrigues RS, Perez RM. Higher cut-off values of non-invasive methods might be needed to detect moderate-to-severe steatosis in morbid obese patients: a pilot study. Sci Rep. 2020;10:15007. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Francque SM, Verrijken A, Mertens I, Hubens G, Van Marck E, Pelckmans P, Michielsen P, Van Gaal L. Noninvasive assessment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in obese or overweight patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1162-8; quiz e87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Otsubo N, Fukuda T, Cho G, Ishibashi F, Yamada T, Monzen K. Utility of Indices Obtained during Medical Checkups for Predicting Fatty Liver Disease in Non-obese People. Intern Med. 2023;62:2307-2319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Chan WK. Comparison between obese and non-obese nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2023;29:S58-S67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Mózes FE, Lee JA, Selvaraj EA, Jayaswal ANA, Trauner M, Boursier J, Fournier C, Staufer K, Stauber RE, Bugianesi E, Younes R, Gaia S, Lupșor-Platon M, Petta S, Shima T, Okanoue T, Mahadeva S, Chan WK, Eddowes PJ, Hirschfield GM, Newsome PN, Wong VW, de Ledinghen V, Fan J, Shen F, Cobbold JF, Sumida Y, Okajima A, Schattenberg JM, Labenz C, Kim W, Lee MS, Wiegand J, Karlas T, Yılmaz Y, Aithal GP, Palaniyappan N, Cassinotto C, Aggarwal S, Garg H, Ooi GJ, Nakajima A, Yoneda M, Ziol M, Barget N, Geier A, Tuthill T, Brosnan MJ, Anstee QM, Neubauer S, Harrison SA, Bossuyt PM, Pavlides M; LITMUS Investigators. Diagnostic accuracy of non-invasive tests for advanced fibrosis in patients with NAFLD: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Gut. 2022;71:1006-1019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 346] [Cited by in RCA: 353] [Article Influence: 88.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 65. | Elsabaawy M, Naguib M, Abuamer A, Shaban A. Comparative application of MAFLD and MASLD diagnostic criteria on NAFLD patients: insights from a single-center cohort. Clin Exp Med. 2025;25:36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Wernberg CW, Ravnskjaer K, Lauridsen MM, Thiele M. The Role of Diagnostic Biomarkers, Omics Strategies, and Single-Cell Sequencing for Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Severely Obese Patients. J Clin Med. 2021;10:930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Soldera J, Dellamea B, Giovanardi H. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and bariatric surgery: Where are we now? Int J Sci Res. 2019;8:4-6. |

| 68. | Zhou YJ, Wong VW, Zheng MH. Consensus scoring systems for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: an unmet clinical need. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2021;10:388-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Kabisch S, Bäther S, Dambeck U, Kemper M, Gerbracht C, Honsek C, Sachno A, Pfeiffer AFH. Liver Fat Scores Moderately Reflect Interventional Changes in Liver Fat Content by a Low-Fat Diet but Not by a Low-Carb Diet. Nutrients. 2018;10:157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Xia MF, Yki-Järvinen H, Bian H, Lin HD, Yan HM, Chang XX, Zhou Y, Gao X. Influence of Ethnicity on the Accuracy of Non-Invasive Scores Predicting Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0160526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | van Dijk AM, Vali Y, Mak AL, Galenkamp H, Nieuwdorp M, van den Born BJ, Holleboom AG. Noninvasive tests for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a multi-ethnic population: The HELIUS study. Hepatol Commun. 2023;7:e2109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Sookoian S, Pirola CJ. Genetic predisposition in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2017;23:1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Park JM, Park DH, Song Y, Kim JO, Choi JE, Kwon YJ, Kim SJ, Lee JW, Hong KW. Understanding the genetic architecture of the metabolically unhealthy normal weight and metabolically healthy obese phenotypes in a Korean population. Sci Rep. 2021;11:2279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Murayama K, Okada M, Tanaka K, Inadomi C, Yoshioka W, Kubotsu Y, Yada T, Isoda H, Kuwashiro T, Oeda S, Akiyama T, Oza N, Hyogo H, Ono M, Kawaguchi T, Torimura T, Anzai K, Eguchi Y, Takahashi H. Prediction of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Using Noninvasive and Non-Imaging Procedures in Japanese Health Checkup Examinees. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11:132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Eremić-Kojić N, Đerić M, Govorčin ML, Balać D, Kresoja M, Kojić-Damjanov S. Assessment of hepatic steatosis algorithms in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Hippokratia. 2018;22:10-16. [PubMed] |

| 76. | Chen LD, Huang JF, Chen QS, Lin GF, Zeng HX, Lin XF, Lin XJ, Lin L, Lin QC. Validation of fatty liver index and hepatic steatosis index for screening of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in adults with obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome. Chin Med J (Engl). 2019;132:2670-2676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Hang Y, Lee C, Roman YM. Assessing the clinical utility of major indices for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in East Asian populations. Biomark Med. 2023;17:445-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Mikolasevic I, Domislovic V, Krznaric-Zrnic I, Krznaric Z, Virovic-Jukic L, Stojsavljevic S, Grgurevic I, Milic S, Vukoja I, Puz P, Aralica M, Hauser G. The Accuracy of Serum Biomarkers in the Diagnosis of Steatosis, Fibrosis, and Inflammation in Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Comparison to a Liver Biopsy. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022;58:252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Hernandez Roman J, Siddiqui MS. The role of noninvasive biomarkers in diagnosis and risk stratification in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab. 2020;3:e00127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Jung TY, Kim MS, Hong HP, Kang KA, Jun DW. Comparative Assessment and External Validation of Hepatic Steatosis Formulae in a Community-Based Setting. J Clin Med. 2020;9:2851. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Melania G, Luisella V, Salvina DP, Francesca G, Amedea Silvia T, Fabrizia B, Maristella M, Filomena N, Kyriazoula C, Vassalle C. Concordance between indirect fibrosis and steatosis indices and their predictors in subjects with overweight/obesity. Eat Weight Disord. 2022;27:2617-2627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Lind L, Johansson L, Ahlström H, Eriksson JW, Larsson A, Risérus U, Kullberg J, Oscarsson J. Comparison of four non-alcoholic fatty liver disease detection scores in a Caucasian population. World J Hepatol. 2020;12:149-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Dyson JK, Anstee QM, McPherson S. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a practical approach to diagnosis and staging. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2014;5:211-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 257] [Article Influence: 21.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Bassal T, Basheer M, Boulos M, Assy N. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease-A Concise Review of Noninvasive Tests and Biomarkers. Metabolites. 2022;12:1073. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Onzi G, Moretti F, Balbinot SS, Balbinot RA, Soldera J. Hepatocellular carcinoma in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with and without cirrhosis. Hepatoma Res. 2019;5:7. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Miele L, Zocco MA, Pizzolante F, De Matthaeis N, Ainora ME, Liguori A, Gasbarrini A, Grieco A, Rapaccini G. Use of imaging techniques for non-invasive assessment in the diagnosis and staging of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism. 2020;112:154355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/