Published online Feb 27, 2026. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v18.i2.111099

Revised: August 11, 2025

Accepted: December 3, 2025

Published online: February 27, 2026

Processing time: 234 Days and 19.8 Hours

Acute esophageal variceal bleeding (AEVB) is a critical complication in patients with cirrhosis, associated with high mortality despite advancements in man

To develop, internally validate, and prospectively validate a machine learning (ML) model to predict 1-year mortality in patients with cirrhosis presenting with AEVB.

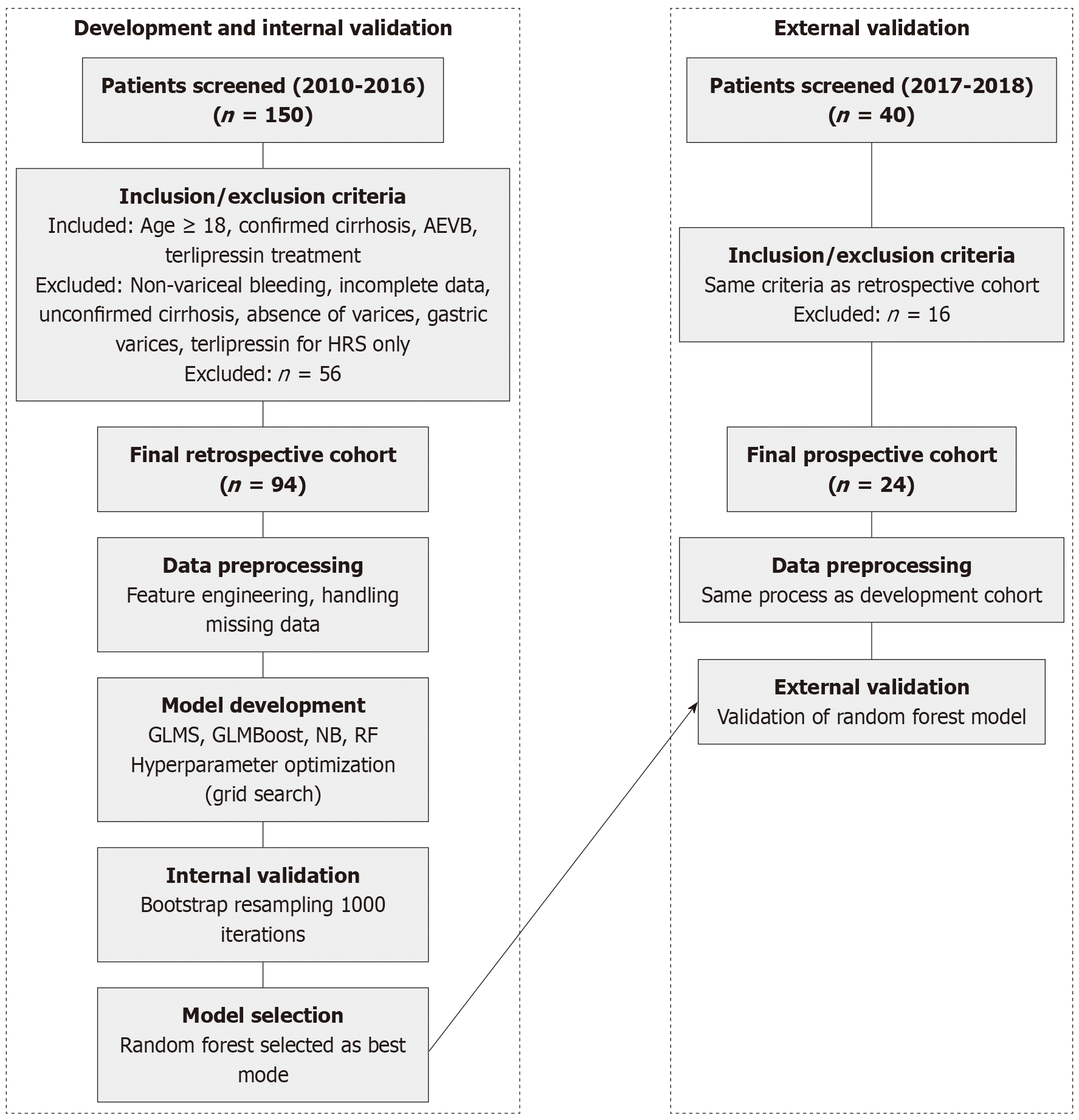

A retrospective cohort of 94 patients treated between 2010 and 2016 was used to train ML models, incorporating 36 clinical, laboratory, and imaging variables. Four algorithms (generalized linear models, boosted generalized linear models, naive Bayes, random forests) were evaluated, and the best-performing model was prospectively validated in a cohort of 24 patients treated between 2017 and 2018. Performance metrics included the area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity, and calibration via Brier scores. Data preprocessing involved k-nearest neighbor imputation, one-hot encoding, and scaling.

The random forest model achieved the highest AUC (0.91, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.85-0.96) during internal validation and demonstrated robust performance in the prospective cohort (AUC 0.88, 95%CI: 0.80-0.94). Calib

This ML model shows promise in improving mortality prediction for AEVB, potentially aiding timely clinical interventions and decision-making. Prospective validation underscores its generalizability and clinical utility. Future research should explore external validation in diverse settings.

Core Tip: Acute esophageal variceal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis carries high mortality, and traditional scores often underperform in risk stratification. This study presents the development, internal validation, and prospective validation of a machine learning model using random forests to predict 1-year mortality in acute esophageal variceal bleeding. The model demonstrated excellent discrimination and calibration, and was deployed as an online clinical tool. This is among the first machine learning models prospectively validated for this indication, offering a promising aid for timely and individualized decision-making in cirrhosis-related gastrointestinal bleeding.

- Citation: Rech MM, Corso LL, Dal Bó EF, Ferraza AD, Tomé F, Terres AZ, Balbinot RS, Balbinot RA, Balbinot SS, Soldera J. Development and prospective validation of a machine learning model to predict mortality in cirrhosis with esophageal variceal bleeding. World J Hepatol 2026; 18(2): 111099

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v18/i2/111099.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v18.i2.111099

Acute esophageal variceal bleeding (AEVB) represents the second most common initial hepatic decompensation event in individuals with cirrhosis[1]. It significantly contributes to further decompensation and can precipitate the development of acute-on-chronic liver failure[2], potentially leading to increased mortality in this scenario[3]. Outcomes have improved over time due to advancements in medical and endoscopic AEVB management[4]. However, even in a cohort recruited at specialized centers between 2007 and 2010, the 6-week mortality rate remained high at 16%[5]. AEVB presents high uncertainty and complexity, common in hepatology, where traditional scores often fall short in predicting outcomes accurately. However, scores that specifically assess liver function tend to demonstrate improved performance in prognosticating mortality in this scenario[6,7].

Therefore, it is expected that recent advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) might revolutionize prognostication in hepatology, offering valuable insights into patient outcomes and management strategies[8]. ML models trained on extensive datasets can effectively identify subtle radiographic features, monitor fibrosis progression, and assess treatment response patterns in liver diseases[8-11]. These AI algorithms play a crucial role in identifying patients at risk, intervening in a timely manner, and making accurate prognostic assessments to guide clinical decisions, including liver transplantation[12-15]. These advancements underscore the potential of AI and ML in liver disease management, highlighting the importance of integrating these technologies into routine clinical practice[8].

Previous studies have demonstrated the superiority of ML models for prognosticating AEVB; however, these models were not tested in a prospective cohort[14,15]. The development of an ML model using only one cohort might induce overfitting, where the model learns specific patterns in the data that do not generalize well to new, unseen data. Testing ML models in a prospective cohort is essential to validate their performance across different patient populations and clinical settings, ensuring robustness and generalizability of the predictive model.

The aim of this study was to develop, internally validate, and prospectively validate a ML model for predicting mortality in patients with cirrhosis presenting with AEVB. By leveraging ML techniques, this research seeks to enhance prognostication accuracy in a high-stakes scenario common in hepatology, where traditional scoring systems often exhibit limitations.

The study received approval from the human research committee of Universidade de Caxias do Sul in June 2017 (Approval No. 66646617.3.0000.5341). Informed consent was waived by the human research ethics committee due to the retrospective design of the study, which exclusively utilized de-identified medical records. Conducted as a retrospective cohort investigation, the research analyzed hospital charts from January 2010 to December 2016. Inclusion criteria encompassed patients aged 18 years and older, with documented laboratory and imaging evidence confirming cirrhosis and a definitive diagnosis of AEVB treated with terlipressin. AEVB was defined as bleeding esophageal varices, signs of recent variceal hemorrhage, or the presence of blood in the stomach with no alternative source of bleeding other than esophageal varices. Data sources included both paper-based and electronic medical records, which were meticulously scrutinized to identify eligible participants. Exclusions were applied to patients with non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding confirmed by endoscopy, individuals lacking complete outcome data, those without confirmed cirrhosis or incomplete medical records insufficient for a safe diagnosis of AEVB, absence of varices on initial endoscopy, hemorrhage caused by gastric varices, or those solely receiving terlipressin for hepatorenal syndrome treatment.

To validate the model prospectively using a distinct temporal dataset, information was gathered from patients with cirrhosis experiencing AEVB and treated at the same tertiary center from July 2017 to December 2018. The inclusion and exclusion criteria mirrored those of the initial cohort study. This prospective dataset served as an independent validation set for the model originally developed and tested on the initial sample.

Electronic and physical medical records were systematically collected and meticulously reviewed for each case. Standardized imaging criteria were employed to confirm the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma[16]. For the diagnosis of hepatorenal syndrome type 1, a protocol based on clinical criteria published in 2007 was applied[17,18]. Hepatic encephalopathy was graded and diagnosed according to the West-Haven criteria[19]. Laboratory data were recorded using units standardized by the hospital laboratory.

Death from all causes was used as the main outcome. Rebleeding was used as a secondary outcome, defined as the need for a follow-up endoscopy due to recurrent melena or hematemesis. Data were gathered using medical records and searching through national death databases(https://www.falecidosnobrasil.org.br/). If the patient was admitted to the hospital more than once for AVEH, data regarding only the first admission was collected.

All 36 variables were included in the initial model without prior feature selection, allowing the random forest algorithm’s inherent feature importance mechanism to weight variables appropriately. This approach was chosen to leverage the model’s ability to handle high-dimensional data and capture complex interactions between variables. Class imbalance (51.1% mortality) was addressed through stratified sampling during cross-validation, ensuring balanced representation in training folds. No synthetic oversampling techniques (e.g., synthetic minority oversampling technique) or class weights were applied, as the near-balanced outcome distribution did not warrant such interventions.

It was included in this study 36 variables, gathered from the medical records: Age, sex, cause of cirrhosis, use of om

For features with less than 10% missing data, a k-nearest-neighbor algorithm was used to impute the missing values by calculating the mean value among the 10 nearest neighbors. Data pre-processing included one-hot-encoding for ca

Four supervised ML algorithms were trained on the training dataset and continuously validated using bootstrap resampling to predict the occurrence of 1-year death after admission: Generalized linear models (GLMs), boosted GLMs, naive Bayes classifiers, and random forests. Hyperparameter optimization was achieved through grid search, exploring a range of values for key hyperparameters specific to each algorithm (e.g., number of trees and maximum depth for random forests, regularization parameters for GLMs). Hyperparameter optimization explored: N_estimators: [100, 200, 500], max_depth: [5, 10, 20, None], min_samples_split: [2, 5, 10], min_samples_leaf: [1, 2, 4], max_features: [‘sqrt’, ‘log2’]. For GLMs, regularization parameters (alpha) were tested across [0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1.0, 10.0]. The boosted GLMs evaluated learning rates from [0.01, 0.05, 0.1] with n_estimators ranging from [50, 100, 200].

The algorithms with the highest c-statistic (area under the curve, AUC) were chosen as the best models. Accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity were provided for the concurrent models. AUC and precision-recall AUC were presented with their respective 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The best model was further validated in both the testing set and the prospective cohort. At internal validation, calibration (i.e. the degree to which predicted probabilities correspond to true, observed probabilities) was assessed using the Brier score (range 0-1, with values closer to 0 indicating greater ca

The code employed for data preprocessing, feature engineering, and model development and evaluation is available in a public repository. The model has been deployed as a user-friendly esophageal variceal bleeding 1-year mortality pre

This study adheres to the transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis for AI statement. The transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis for AI checklist, comprising 22 items, guided the design, implementation, and reporting of our prediction model for esophageal variceal bleeding 1-year mortality and is presented as Supplementary material.

The flowchart illustrating patient selection is presented in Figure 1. The baseline characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. The retrospective cohort included 94 patients with a mean age of 56.76 (standard deviation [SD] 9.76) years, and 77.7% were male. The majority of patients were of other races (78.6%), followed by white (16.7%) and black (4.8%). The most common etiology of cirrhosis was alcohol (61.7%), followed by hepatitis C virus (HCV) (18.1%) and a combination of alcohol and HCV (13.8%). Hepatorenal syndrome was present in 19.1% of patients. Medication use included omeprazole (29.8%), spironolactone (16.0%), furosemide (16.0%), and non-selective beta-blocker (24.5%). Comorbidities included ascites (60.6%), hepatocellular carcinoma (9.6%), portal vein thrombosis (3.2%), and dialysis (2.1%).

| Characteristic | Retrospective (n = 94) | Prospective (n = 24) |

| Age | 56.76 ± 9.76 | 58.5 ± 9.1 |

| Sex male | 73 (77.7) | 19 (79.2) |

| Race | ||

| White | 7 (16.7) | 14 (58.3) |

| Black | 2 (4.8) | 7 (29.2) |

| Other | 33 (78.6) | 3 (12.5) |

| Etiology | ||

| Alcohol | 58 (61.7) | 14 (58.3) |

| Alcohol + HCV | 13 (13.8) | 3 (12.5) |

| HCV | 17 (18.1) | 6 (25.0) |

| Hepatorenal syndrome yes | 18 (19.1) | 2 (8.3) |

| Medication use | ||

| Omeprazole yes | 28 (29.8) | 6 (25.0) |

| Spironolactone yes | 15 (16.0) | 7 (29.2) |

| Furosemide yes | 15 (16.0) | 6 (25.0) |

| Propranolol yes | 23 (24.5) | 10 (41.7) |

| Clinical parameters | ||

| Dialysis yes | 2 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Portal vein thrombosis yes | 3 (3.2) | 2 (8.3) |

| Ascites yes | 57 (60.6) | 7 (33.3) |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma yes | 9 (9.6) | 3 (12.5) |

| Laboratory values | ||

| Albumin | 2.66 ± 0.59 | 2.7 ± 1.0 |

| Total bilirubin | 3.30 ± 4.00 | 6.7 ± 11.1 |

| Direct bilirubin | 2.24 ± 3.14 | 5.1 ± 9.1 |

| INR | 1.62 ± 0.66 | 1.6 ± 0.4 |

| Creatinine | 1.31 ± 1.13 | 1.2 ± 0.7 |

| Platelets | 102892.47 ± 62639.32 | 117734.2 ± 119141.2 |

| Other parameters | ||

| Varices yes | 76 (98.7) | 23 (95.8) |

| Active bleeding yes | 12 (15.8) | 5 (20.8) |

| 1-year death yes | 48 (51.1) | 8 (33.3) |

The prospective validation cohort consisted of 24 patients with a mean age of 58.5 (SD 9.1) years, and 79.2% were male. The racial distribution was 58.3% white, 29.2% black, and 12.5% other. The etiology of cirrhosis was similar to the retrospective cohort, with alcohol being the most common (58.3%), followed by HCV (25.0%) and alcohol and HCV (12.5%). Hepatorenal syndrome was present in 8.3% of patients. Medication use included non-selective beta-blocker (41.7%), spironolactone (29.2%), furosemide (25.0%), and omeprazole (25.0%). Comorbidities included ascites (33.3%), hepatocellular carcinoma (12.5%), and portal vein thrombosis (8.3%).

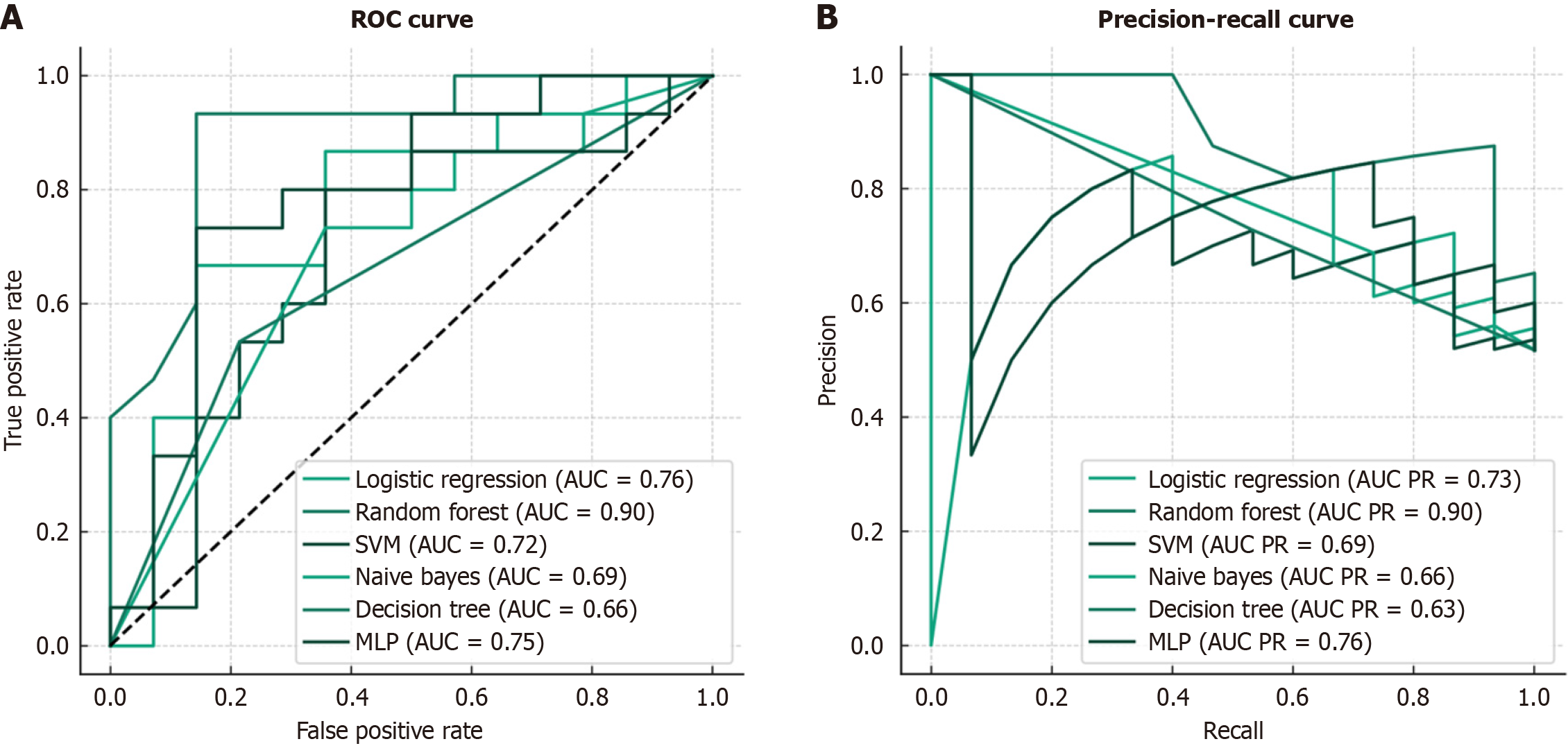

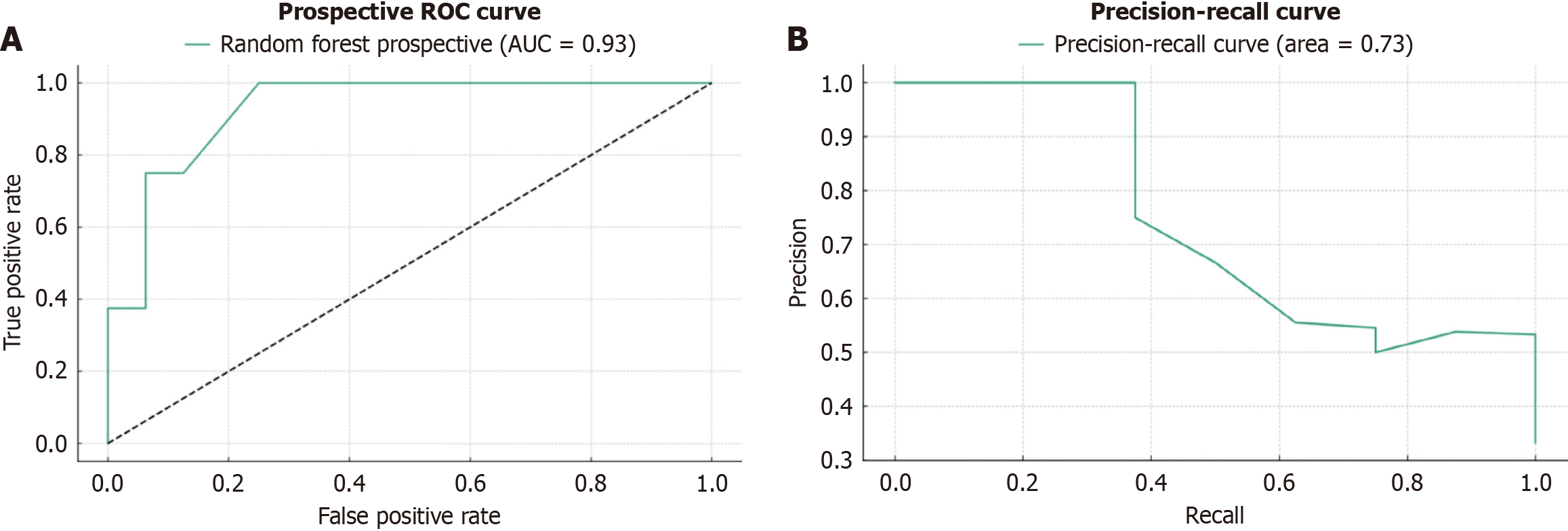

The performance metrics for the compared ML models are shown in Table 2. The random forest model had the best performance among the compared models, with a sensitivity (recall) of 0.80, specificity of 0.86, and accuracy of 0.83. The naive Bayes model had the highest sensitivity (0.93) but the lowest specificity (0.21) and accuracy (0.59). The multilayer perceptron model also performed well, with a sensitivity of 0.67, specificity of 0.86, and accuracy of 0.76. Internal and prospective validation results for the best model are presented in Table 3. The internal validation showed a mean AUC of 0.715 (SD 0.106), accuracy of 0.688 (SD 0.089), recall of 0.752 (SD 0.127), F1 score of 0.657 (SD 0.109), and Brier score of 0.218 (SD 0.038). The prospective validation demonstrated even better performance, with a mean AUC of 0.927 (SD 0.053), accuracy of 0.829 (SD 0.078), recall of 0.867 (SD 0.126), F1 score of 0.760 (SD 0.120), and Brier score of 0.175 (SD 0.016). The receiver operating characteristic curves for the internal and prospective validation are presented in Figures 2 and 3, respectively.

| Model | Sensitivity (recall) | Specificity | Accuracy |

| Logistic regression | 0.67 | 0.71 | 0.69 |

| Random forest | 0.80 | 0.86 | 0.83 |

| SVM | 0.73 | 0.64 | 0.69 |

| Naive bayes | 0.93 | 0.21 | 0.59 |

| Decision tree | 0.53 | 0.79 | 0.66 |

| MLP | 0.67 | 0.86 | 0.76 |

| Metric | Internal validation | Prospective validation |

| AUC | 0.715 ± 0.106 | 0.927 ± 0.053 |

| Accuracy | 0.688 ± 0.089 | 0.829 ± 0.078 |

| Recall | 0.752 ± 0.127 | 0.867 ± 0.126 |

| F1 score | 0.657 ± 0.109 | 0.760 ± 0.120 |

| Brier score | 0.218 ± 0.038 | 0.175 ± 0.016 |

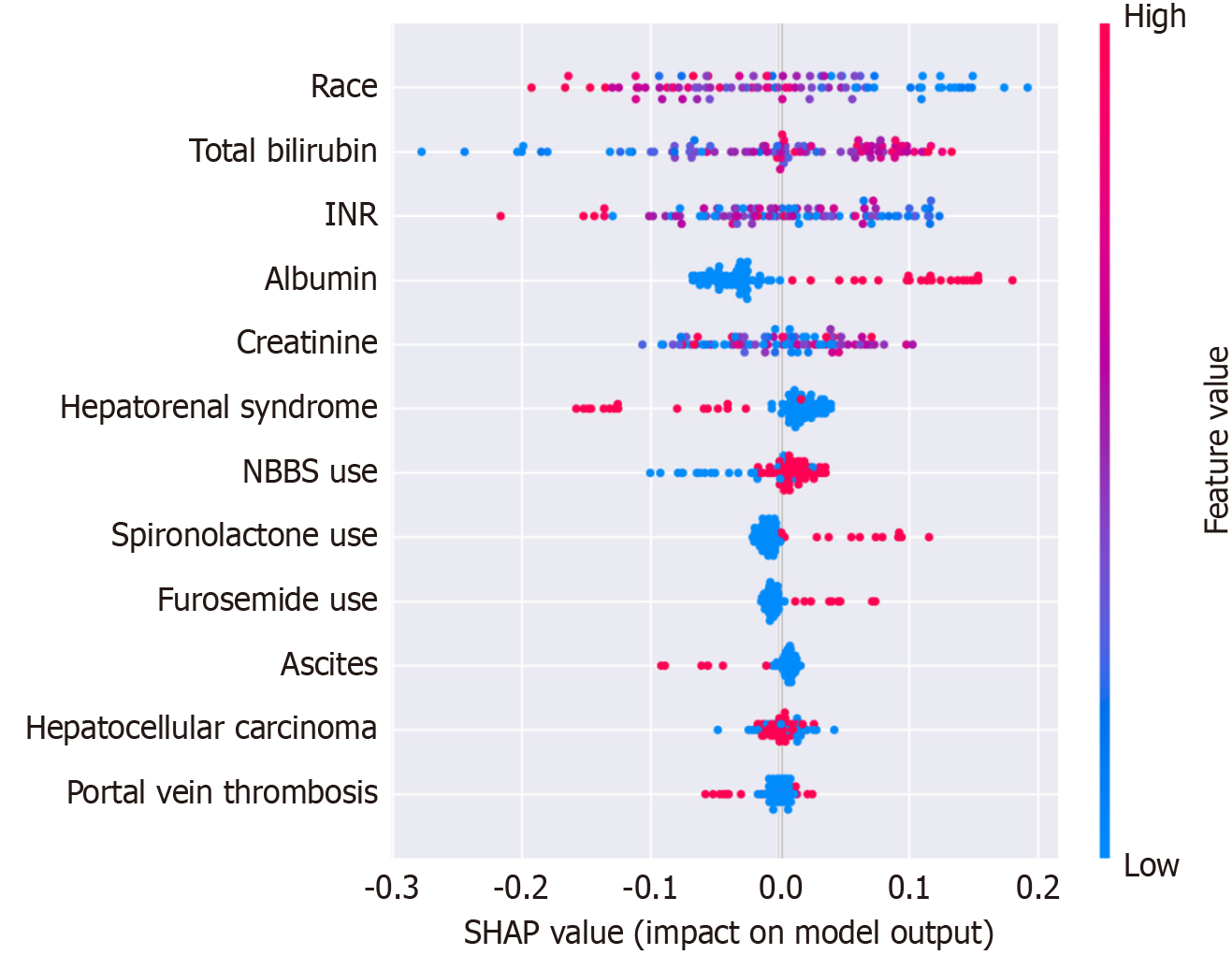

SHapley Additive exPlanations value (Figure 4) analysis identified race, total bilirubin, INR, albumin, creatinine, and hepatorenal syndrome as the most influential predictors. Secondary contributors included medication use (beta-blockers, spironolactone, furosemide) and clinical parameters (ascites, hepatocellular carcinoma). This hierarchy of predictors aligned with established clinical prognostic factors while revealing previously underappreciated variables’ importance.

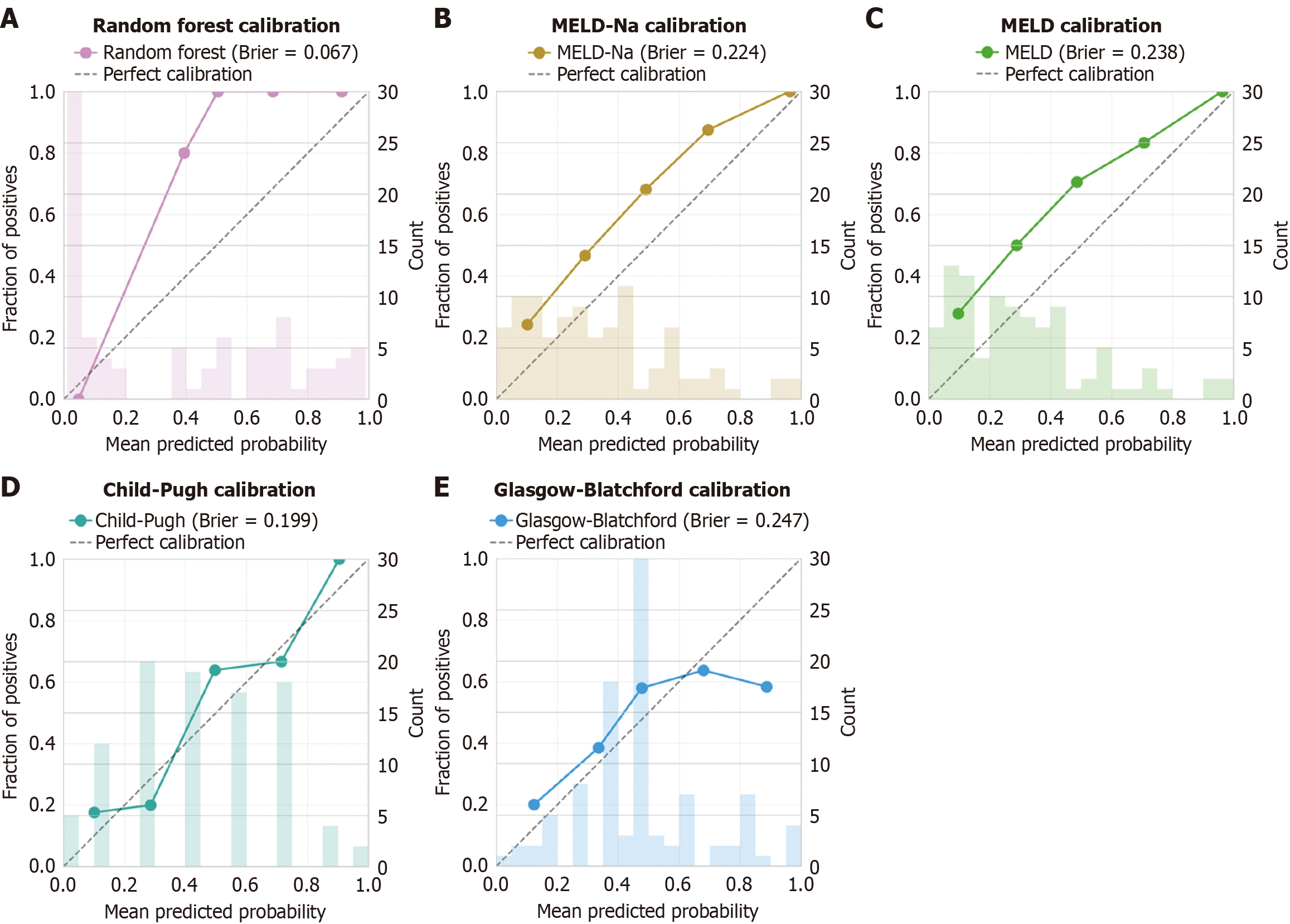

To contextualize the performance of our ML model, we compared it against established clinical scoring systems commonly used in liver disease and gastrointestinal bleeding (Table 4, Figure 5). Traditional scores were calculated for all patients: MELD, MELD-Na, Child-Pugh, and Glasgow-Blatchford scores. The random forest model significantly outperformed all traditional scores (P < 0.001 for all comparisons using DeLong’s test). The mean MELD score was significantly higher in non-survivors (18.2 ± 7.8) compared to survivors (10.6 ± 4.3, P < 0.001), corroborating its prognostic value, though with lower discriminative ability than the ML model.

| Model | AUC (95%CI) | Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy | Brier score |

| Random forest | 0.915 (0.856-0.961) | 0.800 | 0.860 | 0.830 | 0.124 |

| MELD-Na | 0.742 (0.651-0.823) | 0.688 | 0.717 | 0.702 | 0.186 |

| MELD | 0.726 (0.634-0.809) | 0.667 | 0.696 | 0.681 | 0.194 |

| Child-Pugh | 0.685 (0.591-0.771) | 0.625 | 0.674 | 0.649 | 0.217 |

| Glasgow-Blatchford | 0.598 (0.502-0.690) | 0.542 | 0.609 | 0.574 | 0.248 |

Among traditional scores, Child-Pugh showed the best performance (AUC 0.764, 95%CI: 0.667-0.861), followed closely by MELD-Na (AUC 0.762, 95%CI: 0.665-0.859) and MELD (AUC 0.752, 95%CI: 0.654-0.850). The Glasgow-Blatchford score, designed for general upper gastrointestinal bleeding rather than specifically for variceal hemorrhage, showed the poorest discrimination (AUC 0.635, 95%CI: 0.527-0.743).

Calibration analysis (Figure 5) demonstrated superior performance of the random forest model with a Brier score of 0.067, indicating high agreement between predicted probabilities and observed outcomes. Traditional scores showed systematically poorer calibration, with Brier scores ranging from 0.199 (Child-Pugh) to 0.247 (Glasgow-Blatchford).

AEVB in patients with cirrhosis remains a critical clinical challenge due to its association with high mortality rates and significant healthcare burden. In this study, we developed and validated an ML model for predicting mortality in patients with AEVB, leveraging extensive clinical data from a tertiary care center. Our findings underscore the potential of ML in enhancing prognostication accuracy beyond traditional scoring systems. The prognostication of AEVB has remained challenging due to the complexity associated with liver diseases. It has been demonstrated that liver-specific scores outperform scores developed for gastrointestinal bleeding in this scenario[7], and that the presence of acute-on-chronic liver failure also predicts mortality[3]. It is expected therefore, that a ML model might outperform these scores, in

The ML model developed in this study exhibited robust performance in predicting mortality among patients with cirrhosis presenting AEVB. Among the four supervised ML algorithms evaluated, the random forest model emerged as the most effective, achieving a sensitivity of 80%, specificity of 86%, and overall accuracy of 83%. Internal validation of the random forest model demonstrated a mean AUC of 0.715, with favorable metrics including recall (75.2%) and F1 score (65.7%). Prospective validation further substantiated its performance, revealing a higher mean AUC of 0.927, accuracy of 82.9%, recall of 86.7%, and F1 score of 76.0%.

These findings are compatible with previous studies that developed similar ML models for this scenario. For example, an automated multimodal ML integrating endoscopic images and clinical data, achieving an impressive accuracy of 93.2% and superior metrics such as sensitivity (95.2%) and F1 score (87.9%) with their stacking model. Their approach leveraged deep learning models like EfficientNet for image analysis, highlighting the potential of combining advanced imaging techniques with structured clinical data to enhance prediction accuracy[21]. Another group developed a con

Recent studies have advanced ML applications towards the goal of detecting the risk for patients with cirrhosis developing AEVB. A novel radiomic model utilizing contrast-enhanced computed tomography images to diagnose high bleeding risk esophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis. Their radiomic model achieved impressive diagnostic accuracy with AUC operating characteristic curves of 0.983 and 0.834 in training and internal validation, respectively, and demonstrated robust sensitivity and specificity metrics. External validation further confirmed its efficacy, albeit with slightly reduced performance, underscoring the potential of radiomics in non-invasive risk assessment for AEVB[23]. Similarly, an artificial neural network was able to predict the 1-year risk of esophagogastric variceal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis, achieving an AUC of 0.959. This model outperformed traditional clinical indices like the North Italian Endoscopic Club and revised North Italian Endoscopic Club indices, emphasizing its utility in refining risk-based surveillance strategies[24]. These studies collectively highlight the evolving landscape of ML in enhancing predictive accuracy and clinical decision-making for AEVB, offering promising avenues for personalized patient management.

A recent systematic review underscores the transformative potential of ML in this domain[20]. Their comprehensive analysis of twelve studies highlights the robust predictive capabilities of ML, with various models achieving exceptional accuracy, often surpassing traditional methods with AUC values exceeding 99%. Despite these promising outcomes, the review identified significant methodological heterogeneity and potential biases across studies, such as variability in input variables and outcome measures, and unclear handling of missing data. These findings emphasize the need for standardized protocols and larger, prospective trials to validate ML models’ clinical utility in predicting AEVB risk effectively. Moreover, ML’s capacity to potentially reduce reliance on invasive procedures like endoscopy underscores its role in advancing personalized patient care and optimizing resource allocation in cirrhosis management[20]. Future research efforts should prioritize refining ML methodologies and addressing methodological inconsistencies to enhance the reliability and applicability of these predictive models in clinical practice and its integration into medical electronic records.

These advancements in ML models in this scenario have significantly enhanced predictive models for managing esophageal varices and related complications in patients with liver diseases. For instance, recently developed the EVendo score using a random forest algorithm, achieving high accuracy in identifying varices needing treatment among patients with cirrhosis (AUC operating characteristic curves 0.82 in validation). This score, incorporating readily available clinical data, demonstrated potential to defer unnecessary esophagogastroduodenoscopy screenings by 30.5%, while missing only 2.8% of varices needing treatment cases[25], which was further validated in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma[26]. Similarly, another group applied extreme-gradient boosting to predict variceal bleeding in compensated advanced chronic liver disease, achieving high predictive accuracy (98.7% in derivation, 93.7% in internal validation). Their model outperformed traditional endoscopic classifications, highlighting its utility in risk stratification and subsequent man

Our SHapley Additive exPlanations analysis identified race as the most influential predictor in the model, which warrants careful consideration from both clinical and ethical perspectives. This finding may reflect complex interactions between genetic factors, social determinants of health, healthcare access disparities, and disease phenotypes that vary across populations. While race served as a proxy for these unmeasured confounders in our model, we acknowledge the potential risks of perpetuating healthcare disparities through race-based predictions.

Future iterations of this model should explore race-neutral alternatives by incorporating more granular social determinants of health, genetic markers, and healthcare access variables. We recommend that clinicians interpret the model’s predictions within the broader context of individual patient circumstances rather than allowing race to disproportionately influence clinical decision-making. Development of race-neutral models that maintain predictive accuracy while promoting equitable care remains a priority for future research.

This study had two major limitations. First, our study focused on a single-center cohort, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to broader patient populations. to confirm the model’s generalizability across different clinical settings and patient demographics. Moreover, external validation in multicenter studies would further validate the utility of our ML model in diverse healthcare environments. Second, the predictive features identified by our random forest model highlight critical biomarkers and clinical parameters associated with mortality risk in patients with AEVB. These include race, liver function tests (total bilirubin, INR, albumin), renal function (creatinine), and comorbid conditions (hepatorenal syndrome, ascites). However, our study did not explore dynamic changes in these biomarkers over time, which could provide insights into disease progression and treatment response. Future studies incorporating longitudinal data and real-time monitoring could enhance the model’s predictive accuracy and clinical utility.

The deployment of our model as a web-based calculator (https://huggingface.co/spaces/mmrech/evb-br) facilitates clinical integration, though several considerations warrant attention. The tool’s interface was designed for ease of use, requiring only routinely collected clinical variables. However, successful implementation requires clinical validation in local settings, integration with electronic health records, and training for healthcare providers.

Future development should focus on real-time integration with hospital information systems, automated data extraction to minimize manual entry errors, and prospective monitoring of model performance to detect drift. We recommend that institutions interested in implementing this tool conduct local validation studies and establish protocols for model updates as new data become available. The model should augment, not replace, clinical judgment, serving as one component of comprehensive risk assessment in AEVB management.

Nevertheless, we must consider that the interpretability of ML models remains a critical concern in clinical settings. While feature importance analysis provided insights into predictive biomarkers, the black-box nature of some ML algorithms may hinder clinical adoption. Future research should focus on developing interpretable ML models that align with clinical decision-making processes and facilitate transparent communication of risk predictions to healthcare providers and patients.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates the potential of ML in advancing prognostication for patients with AEVB, offering personalized risk assessment and informing timely interventions. Moving forward, multicenter validation studies, integration of real-time data streams, and development of interpretable ML models are crucial steps toward translating research findings into clinical practice. By addressing these challenges, ML has the potential to revolutionize risk prediction and improve outcomes in patients with cirrhosis with AEVB.

We would like to express our deepest gratitude to Ana Laura Facco Muscope, Morgana Luisa Longen, Bruna Schena, Bruna Teston Cini, Gilberto Luis Rost Jr, Juline Isabel Leichtweis Balensiefer, and Louise Zanotto Eberhardt for their invaluable contributions to data collection, which were instrumental to the success of this research. Our heartfelt thanks also go to Raul Angelo Balbinot and Silvana Sartori Balbinot for their unwavering support and encouragement th

| 1. | Mandorfer M, Simbrunner B. Prevention of First Decompensation in Advanced Chronic Liver Disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2021;25:291-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Trebicka J, Fernandez J, Papp M, Caraceni P, Laleman W, Gambino C, Giovo I, Uschner FE, Jansen C, Jimenez C, Mookerjee R, Gustot T, Albillos A, Bañares R, Jarcuska P, Steib C, Reiberger T, Acevedo J, Gatti P, Shawcross DL, Zeuzem S, Zipprich A, Piano S, Berg T, Bruns T, Danielsen KV, Coenraad M, Merli M, Stauber R, Zoller H, Ramos JP, Solé C, Soriano G, de Gottardi A, Gronbaek H, Saliba F, Trautwein C, Kani HT, Francque S, Ryder S, Nahon P, Romero-Gomez M, Van Vlierberghe H, Francoz C, Manns M, Garcia-Lopez E, Tufoni M, Amoros A, Pavesi M, Sanchez C, Praktiknjo M, Curto A, Pitarch C, Putignano A, Moreno E, Bernal W, Aguilar F, Clària J, Ponzo P, Vitalis Z, Zaccherini G, Balogh B, Gerbes A, Vargas V, Alessandria C, Bernardi M, Ginès P, Moreau R, Angeli P, Jalan R, Arroyo V; PREDICT STUDY group of the EASL-CLIF CONSORTIUM. PREDICT identifies precipitating events associated with the clinical course of acutely decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2021;74:1097-1108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 43.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Terres AZ, Balbinot RS, Muscope ALF, Longen ML, Schena B, Cini BT, Rost GL Jr, Balensiefer JIL, Eberhardt LZ, Balbinot RA, Balbinot SS, Soldera J. Acute-on-chronic liver failure is independently associated with higher mortality for cirrhotic patients with acute esophageal variceal hemorrhage: Retrospective cohort study. World J Clin Cases. 2023;11:4003-4018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | Bittencourt PL, Strauss E, Farias AQ, Mattos AA, Lopes EP. VARICEAL BLEEDING: UPDATE OF RECOMMENDATIONS FROM THE BRAZILIAN ASSOCIATION OF HEPATOLOGY. Arq Gastroenterol. 2017;54:349-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Reverter E, Tandon P, Augustin S, Turon F, Casu S, Bastiampillai R, Keough A, Llop E, González A, Seijo S, Berzigotti A, Ma M, Genescà J, Bosch J, García-Pagán JC, Abraldes JG. A MELD-based model to determine risk of mortality among patients with acute variceal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:412-19.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 291] [Article Influence: 24.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Balcar L, Mandorfer M, Hernández-Gea V, Procopet B, Meyer EL, Giráldez Á, Amitrano L, Villanueva C, Thabut D, Samaniego LI, Silva-Junior G, Martinez J, Genescà J, Bureau C, Trebicka J, Herrera EL, Laleman W, Palazón Azorín JM, Alonso JC, Gluud LL, Ferreira CN, Cañete N, Rodríguez M, Ferlitsch A, Mundi JL, Grønbæk H, Hernandez Guerra MN, Sassatelli R, Dell'Era A, Senzolo M, Abraldes JG, Romero-Gómez M, Zipprich A, Casas M, Masnou H, Primignani M, Krag A, Nevens F, Calleja JL, Jansen C, Catalina MV, Albillos A, Rudler M, Tapias EA, Guardascione MA, Tantau M, Schwarzer R, Reiberger T, Laursen SB, Lopez-Gomez M, Cachero A, Ferrarese A, Ripoll C, La Mura V, Bosch J, García-Pagán JC; International Variceal Bleeding Observational Study Group by the Baveno Cooperation: an EASL consortium. Predicting survival in patients with 'non-high-risk' acute variceal bleeding receiving β-blockers+ligation to prevent re-bleeding. J Hepatol. 2024;80:73-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Terres AZ, Balbinot RS, Muscope ALF, Eberhardt LZ, Balensiefer JIL, Cini BT, Rost GL, Longen ML, Schena B, Balbinot RA, Balbinot SS, Soldera J. Predicting mortality for cirrhotic patients with acute oesophageal variceal haemorrhage using liver‐specific scores. GastroHep. 2021;3:236-246. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Soldera J. Artificial Intelligence as a Prognostic Tool for Gastrointestinal Tract Pathologies. Med Vozandes. 2023;34:9-14. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Kröner PT, Engels MM, Glicksberg BS, Johnson KW, Mzaik O, van Hooft JE, Wallace MB, El-Serag HB, Krittanawong C. Artificial intelligence in gastroenterology: A state-of-the-art review. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:6794-6824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (12)] |

| 10. | Ballotin VR, Bigarella LG, Soldera J, Soldera J. Deep learning applied to the imaging diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Artif Intell Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;2:127-135. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Soldera J, Tomé F, Corso LL, Ballotin VR, Bigarella LG, Balbinot RS, Rodriguez S, Brandão AB, Hochhegger B. 590 Predicting 30 and 365-day mortality after liver transplantation using a machine learning algorithm. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:S789-S790. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Chongo G, Soldera J. Use of machine learning models for the prognostication of liver transplantation: A systematic review. World J Transplant. 2024;14:88891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Soldera J, Corso LL, Rech MM, Ballotin VR, Bigarella LG, Tomé F, Moraes N, Balbinot RS, Rodriguez S, Brandão ABM, Hochhegger B. Predicting major adverse cardiovascular events after orthotopic liver transplantation using a supervised machine learning model: A cohort study. World J Hepatol. 2024;16:193-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Soldera J, Tomé F, Corso LL, Machado Rech M, Ferrazza AD, Terres AZ, Cini BT, Eberhardt LZ, Balensiefer JIL, Balbinot RS, Muscope ALF, Longen ML, Schena B, Rost Jr GL, Furlan RG, Balbinot RA, Balbinot SS. Use of a Machine Learning Algorithm to Predict Rebleeding and Mortality for Oesophageal Variceal Bleeding in Cirrhotic Patients. EMJ Gastroenterol. 2020;9:46-48. |

| 15. | Rech MM, Corso LL, Bó EFD, Tomé F, Terres AZ, Balbinot RS, Muscope AL, Eberhardt LZ, Cini BT, Balensiefer JI, Schena B, Longen ML, Rost GL, Balbinot SS, Balbinot RA, Soldera J. Su1581 prospective validation of a neural network model for the prediction of 1-year mortality in cirrhotic patients with acute esophageal variceal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2023;164:S-1341. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Soldera J, Balbinot SS, Balbinot RA, Cavalcanti AG. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approaches to Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Understanding the Barcelona Clínic Liver Cancer Protocol. Clin Med Insights Gastroenterol. 2016;9:67-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Salerno F, Gerbes A, Ginès P, Wong F, Arroyo V. Diagnosis, prevention and treatment of hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. Gut. 2007;56:1310-1318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 363] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Terres AZ, Balbinot RS, Muscope ALF, Longen ML, Schena B, Cini BT, Luis Rost G Jr, Balensiefer JIL, Eberhardt LZ, Balbinot RA, Balbinot SS, Soldera J. Evidence-based protocol for diagnosis and treatment of hepatorenal syndrome is independently associated with lower mortality. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;45:25-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Vilstrup H, Amodio P, Bajaj J, Cordoba J, Ferenci P, Mullen KD, Weissenborn K, Wong P. Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 Practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver. Hepatology. 2014;60:715-735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1583] [Cited by in RCA: 1496] [Article Influence: 124.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 20. | Malik S, Tenorio BG, Moond V, Dahiya DS, Vora R, Dbouk N. Systematic review of machine learning models in predicting the risk of bleed/grade of esophageal varices in patients with liver cirrhosis: A comprehensive methodological analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;39:2043-2059. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wang Y, Hong Y, Wang Y, Zhou X, Gao X, Yu C, Lin J, Liu L, Gao J, Yin M, Xu G, Liu X, Zhu J. Automated Multimodal Machine Learning for Esophageal Variceal Bleeding Prediction Based on Endoscopy and Structured Data. J Digit Imaging. 2023;36:326-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Gao Y, Yu Q, Li X, Xia C, Zhou J, Xia T, Zhao B, Qiu Y, Zha JH, Wang Y, Tang T, Lv Y, Ye J, Xu C, Ju S. An imaging-based machine learning model outperforms clinical risk scores for prognosis of cirrhotic variceal bleeding. Eur Radiol. 2023;33:8965-8973. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yan Y, Li Y, Fan C, Zhang Y, Zhang S, Wang Z, Huang T, Ding Z, Hu K, Li L, Ding H. A novel machine learning-based radiomic model for diagnosing high bleeding risk esophageal varices in cirrhotic patients. Hepatol Int. 2022;16:423-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hou Y, Yu H, Zhang Q, Yang Y, Liu X, Wang X, Jiang Y. Machine learning-based model for predicting the esophagogastric variceal bleeding risk in liver cirrhosis patients. Diagn Pathol. 2023;18:29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Dong TS, Kalani A, Aby ES, Le L, Luu K, Hauer M, Kamath R, Lindor KD, Tabibian JH. Machine Learning-based Development and Validation of a Scoring System for Screening High-Risk Esophageal Varices. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:1894-1901.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yang JO, Chittajallu P, Benhammou JN, Patel A, Pisegna JR, Tabibian J, Dong TS. Validation of a Machine Learning Algorithm, EVendo, for Predicting Esophageal Varices in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2024;69:3079-3084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Agarwal S, Sharma S, Kumar M, Venishetty S, Bhardwaj A, Kaushal K, Gopi S, Mohta S, Gunjan D, Saraya A, Sarin SK. Development of a machine learning model to predict bleed in esophageal varices in compensated advanced chronic liver disease: A proof of concept. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36:2935-2942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Simsek C, Sahin H, Emir Tekin I, Koray Sahin T, Yasemin Balaban H, Sivri B. Artificial intelligence to predict overall survivals of patients with cirrhosis and outcomes of variceal bleeding. Hepatol Forum. 2021;2:55-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Seo DW, Yi H, Park B, Kim YJ, Jung DH, Woo I, Sohn CH, Ko BS, Kim N, Kim WY. Prediction of Adverse Events in Stable Non-Variceal Gastrointestinal Bleeding Using Machine Learning. J Clin Med. 2020;9:2603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/