Published online Jan 27, 2026. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v18.i1.113247

Revised: September 11, 2025

Accepted: November 25, 2025

Published online: January 27, 2026

Processing time: 160 Days and 23.8 Hours

Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) remains a global public health challenge, affecting over 296 million people, many of whom are asymptomatic. Incidentally diagnosed carriers provide a critical window for early intervention and prevention. Under

To evaluate hematological parameters and HBV viral load in incidentally detected asymptomatic hepatitis B surface antigen positive patients during routine health screenings.

A cross-sectional observational study was conducted from June 2024 to March 2025 at Dr. D. Y. Patil Medical College, Hospital and Research Centre a tertiary care hospital in Pune, Maharashtra, India, involving 100 hepatitis B surface anti

Marked variations were detected in hemoglobin levels (P < 0.0001), percentage of neutrophils (P = 0.0006), percentage of lymphocytes (P = 0.0031), serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase activity (P = 0.0013), and alanine aminotransferase levels (P = 0.0001) when comparing HBV-infected individuals with the control group. Con

Incidentally detected HBV infections present an opportunity for early disease detection. Hematological and viral markers can guide clinical decisions. Routine screening and contact tracing are essential strategies to control HBV transmission and progression.

Core Tip: A substantial proportion of hepatitis B virus infections remain undetected due to the asymptomatic nature of silent carriers. This study reveals that incidentally diagnosed hepatitis B surface antigen-positive individuals exhibit significant alterations in hematological and liver function parameters despite lacking clinical symptoms. Findings demonstrate a correlation between viral load and markers of hepatic injury, highlighting the need for vigilant laboratory monitoring. Early identification of subclinical liver involvement offers a critical window for intervention to prevent long-term complications such as cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. This work underscores the importance of integrating routine screening, hematological profiling, and virological assessment in public health strategies targeting hepatitis B virus control.

- Citation: Ratnaparkhi MM, Vyawahare CR, Ratnakar PJ, Gandham NR, Suryawanshi PV. Uncovering silent carriers: Hematological insights and viral burden in incidentally detected hepatitis B virus infection. World J Hepatol 2026; 18(1): 113247

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v18/i1/113247.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v18.i1.113247

Infection with the hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a major worldwide health risk. The World Health Organization recently estimated that 296 million individuals globally suffer from a persistent HBV infection[1,2]. Despite its high prevalence, a substantial proportion of infected individuals remain asymptomatic for prolonged periods, unknowingly carrying and potentially transmitting the virus to others. These individuals often referred to as silent or asymptomatic carriers are typically identified during routine health check-ups, preoperative evaluations, or investigations for unrelated medical conditions[3].

The clinical implications of asymptomatic HBV carriage are profound. Although these individuals may not exhibit overt signs of liver dysfunction, the virus may still be actively replicating within hepatocytes, causing subclinical inflammation and progressive liver damage[4]. If left undetected and untreated, this can eventually lead to serious complications, including chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Moreover, asymptomatic carriers contribute silently to the transmission chain, representing a hidden reservoir that undermines efforts to control and eliminate HBV at the community and global levels[5].

Timely detection of these individuals through routine screening programs offers a crucial opportunity to intervene early in the disease course[6]. By identifying carriers before clinical symptoms develop, healthcare providers can initiate appropriate monitoring strategies, consider antiviral therapy when indicated, and implement measures to reduce the risk of transmission such as educating patients, tracing and screening contacts, and promoting vaccination[7].

Despite the known importance of early identification, there exists a significant gap in the literature concerning the hematological and virological profiles of these incidentally diagnosed HBV carriers[8]. Specifically, the relationship bet

The current study was designed to address this gap. By systematically analyzing the hematological parameters and HBV DNA levels in patients incidentally found to be hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-positive, we aim to gain in

The current study was conducted at Dr. D. Y. Patil Medical College, a tertiary healthcare facility in Pune, Maharashtra, India, along with its affiliated hospital and research center, over a ten-month period, from June 2024 to March 2025. It was designed as a cross-sectional qualitative investigation. Assessing and contrasting the virological, biochemical, and haematological characteristics of people who were found to be asymptomatic carriers of the HBsAg with that of twenty healthy persons who were found to be HBV-free was the main goal. The study site offered a heterogeneous patient popu

Participants were grouped into two distinct categories: (1) HBV group (n = 100): This group consisted of individuals who were incidentally identified as HBsAg-positive during their clinical evaluations. These participants showed no signs or symptoms of hepatitis at the time of diagnosis and were recruited from outpatient/inpatients departments and routine check-ups; and (2) Healthy control group (n = 20): This group comprised age- and gender-matched healthy volunteers who were confirmed negative for HBV markers through serological testing. These individuals had no prior history of liver-related illness, chronic disease, or immunosuppressive conditions and served as a comparative baseline for labo

Participants were eligible to take a part in the investigation provided that they met the conditions that followed: (1) Age: 18 years or above, to ensure the inclusion of adults with comparable physiological characteristics; and (2) Health status: Clinically asymptomatic persons who were identified as HBsAg-positive through routine preoperative screening or general health examinations.

To ensure data integrity and avoid confounding effects, individuals were excluded from the study if they had any of the following conditions: (1) Presence of hepatitis C virus or human immunodeficiency virus co-infection, verified through standard diagnostic procedures; and (2) Immunocompromised states, whether due to congenital immunodeficiencies, chronic illnesses, or ongoing immunosuppressive therapy.

Patient case records were reviewed retrospectively to collect demographic and clinical information. The following para

Demographic information: Including age, sex, and duration of hospital admission (where applicable).

Laboratory parameters: (1) Haematological tests: Haemoglobin levels, total leukocyte count, differential leukocyte count, and platelet count; (2) Biochemical tests: Liver function tests such as serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST), serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (SGPT) or alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), total and direct bilirubin, and serum albumin; and (3) Molecular tests: Quantitative esti

All laboratory analysis were performed in compliance with established protocols approved by National Accreditation Board for Testing and Calibration Laboratories, ensuring accuracy, precision, and quality control in diagnostic testing. The investigations encompassed serological, biochemical, haematological, and molecular assessments as outlined below.

Serological testing for HBsAg: Serum specimens were analyzed for the presence of HBsAg using the Architect HBsAg assay kit on the Abbott ARCHITECT ci8200 platform (Abbott Ireland Diagnostics Division, Lisnamuck, Longford, Ireland). The assay employs a chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay technique. As per the manufacturer’s guidelines, samples with HBsAg concentrations ≥ 0.05 IU/mL were interpreted as reactive. The method is characterized by high analytical sensitivity and specificity, reducing the likelihood of false-positive results and enabling accurate detection of HBV carriers[13,14].

Biochemical analysis - liver function tests: Evaluation of hepatic function was conducted through the measurement of routine liver function test parameters using Architect C8000 system. Serum samples were used to assess enzyme activity and protein levels reflective of hepatic cellular integrity, biliary function, and synthetic capacity using the commercially available Abbott laboratories kits. The key enzymes analyzed were AST/SGOT, ALT/SGPT, total bilirubin and direct (conjugated) bilirubin levels were determined. The ranges over which results were reported were as per the manu

Both aminotransferases are intracellular enzymes predominantly found in hepatocytes, and their elevation in serum indicates hepatocellular injury, inflammation, or necrosis, which are common in viral hepatitis[15]. ALP was measured as a marker of biliary tract health. Elevated ALP levels often suggest cholestasis or intrahepatic bile duct obstruction. Additionally, total bilirubin and direct (conjugated) bilirubin levels were determined. Bilirubin is a byproduct of hae

Haematological analysis: Haematological profiling was performed to assess general systemic health and to identify any alterations in blood cell parameters that may be associated with liver dysfunction or viral infection. DXH900 Hematology analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Chaska, MN, United States) was used to determine complete blood count. One of the pri

Immune status of the subjects was evaluated by determining the total white blood cell count and the differential leukocyte count. Alterations in the white blood cell count or in specific leukocyte subsets (such as neutrophils, lymphocytes, or eosinophils) can reflect underlying inflammatory, infectious, or immunological processes. Furthermore, platelet counts were analyzed as thrombocytopenia is a common haematological manifestation in chronic liver disease, often due to hypersplenism or impaired thrombopoietin production[20]. The haematological data were interpreted alongside biochemical and molecular parameters to provide a comprehensive clinical assessment of both HBV-infected patients and healthy controls.

Quantitative estimation of HBV DNA viral load by real time PCR: Plasma samples were assessed for viral load quantification. QuantStudio 5 (Applied Biosystems, CA, United States) Real time PCR system was used. The chemistry used for this PCR was Taqman probe chemistry. TRUPCR total nucleic acid extraction and HBV viral load kits (M/s 3B BlackBio Dx Ltd., Bhopal, India) were used. To ensure the quality of the extracted DNA from clinical samples, an endogenous control gene was included in the kit. Real time PCR protocol, program set up, channel selection, preparation of standards and result analysis were done as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The assay runs for 40 cycles however no amp

GraphPad Prism (Version 8.0.1) and SPSS software (Version 26.0) were used for the analysis of the data. The data collection’s uniformity was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Regarding patients demographic data, statistical measures were computed, such as frequencies and percentages. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for analyses with data that is continuous. Continuous variables, including hematological and biochemical parameters as well as viral load values, were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U-test. Spearman’s rank correlation analysis was used to look at con

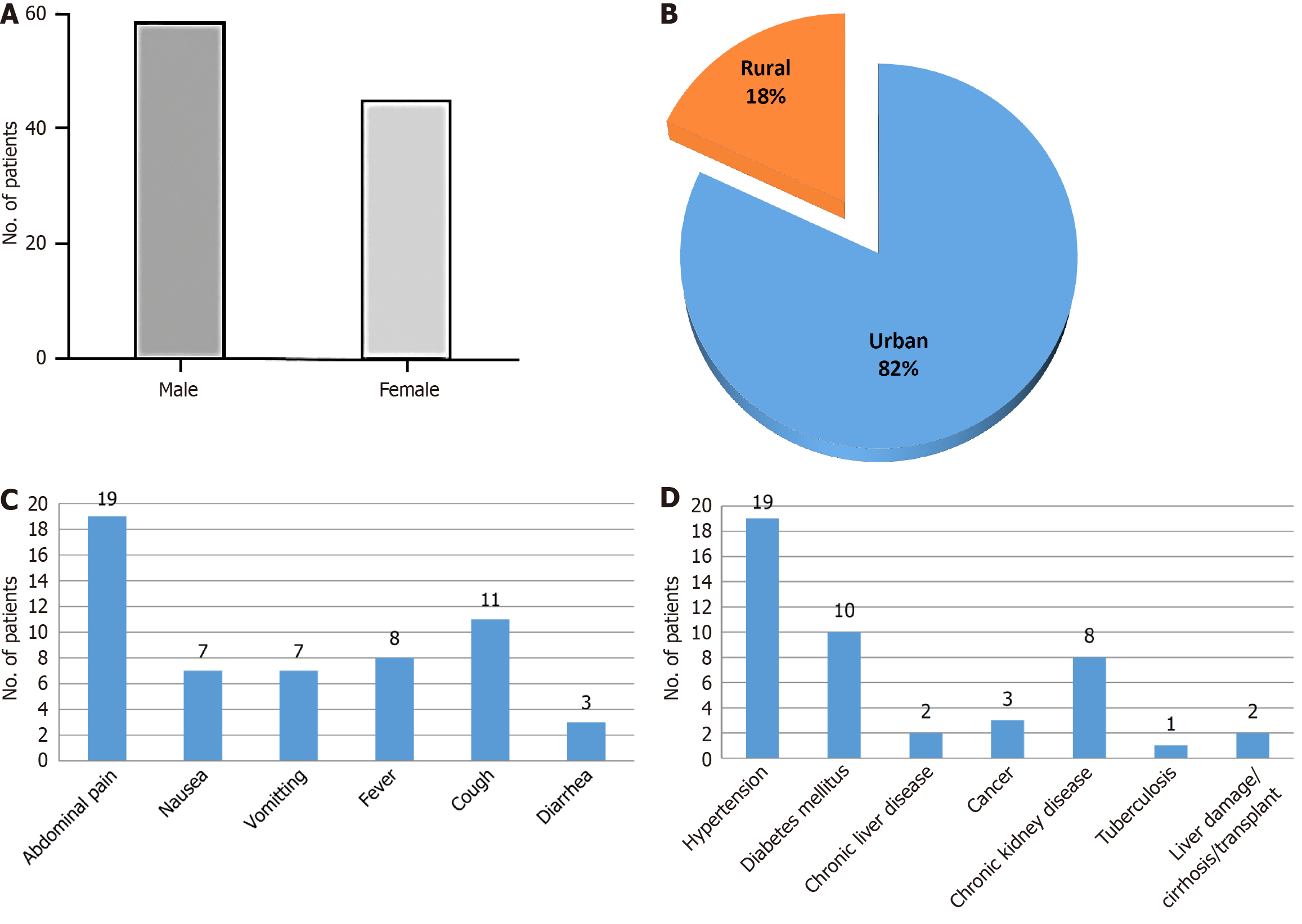

Analysis of the demographic data showed that individuals in the HBV-positive group had an average age of 39.6 ± 12.4 years, placing the majority within the middle-aged category. There was a clear predominance of males, with an approximate male-to-female ratio of 1.8:1. The length of hospital stay was comparable between the HBV-positive and control groups, indicating that asymptomatic HBV infection, in the absence of evident liver-related complications, did not significantly prolong hospitalization (Figure 1A). Enrolled patients were classified based on their residing areas into urban and rural (Figure 1B). Higher infection rates are made possible by urban crowding, frequent migrations and gaps in vaccination coverage among transient populations which may create conditions that favor viral spread, while lower HBV transmission in rural areas may be a result of lower population density and mobility.

The analysis of incidentally detected HBV patients on the basis of clinical presentation showed common complaints of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, fever, cough and diarrhoea (Figure 1C). The co-morbidities associated with these patients were hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic liver disease, cancer, chronic kidney diseases, tuberculosis, liver damage/cirrhosis/transplant (Figure 1D).

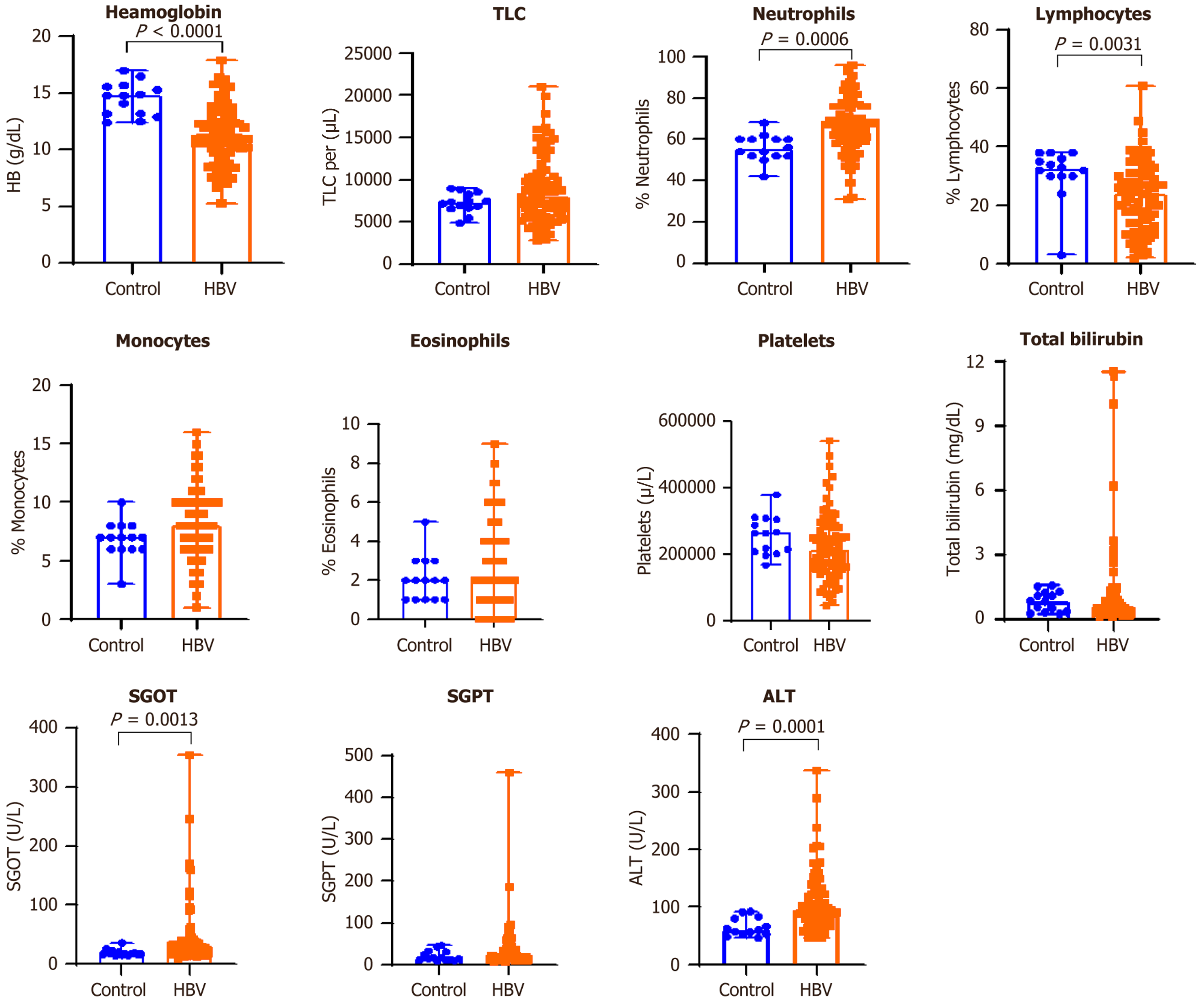

Comparative evaluation between the HBV-positive group and healthy controls revealed statistically significant di

| Parameters | HBV median (range) | Control median (range) |

| Hb (g/dL) | 11.1 (5.3-17.9) | 14.8 (12.4-17) |

| Total leucocytes (WBC) count/μL | 8100 (2800-21000) | 7300 (4900-9000) |

| Platelet count/μL | 217000 (45000-543000) | 264000 (167000-380000) |

| RBC count/μL | 4 (2.14-5.94) | Not done |

| Neutrophils (%) | 67 (32-96) | 55 (42-68) |

| Eosinophils (%) | 2 (0-9) | 2 (1-5) |

| Basophils (%) | 0 | Not done |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 23 (2-45) | 32.5 (3-38) |

| Monocytes (%) | 8 (1-16) | 7 (3-10) |

| Bilirubin-total (mg/dL) | 0.61 (0.16-11.55) | 0.855 (0.26-1.59) |

| Bilirubin-conjugated (mg/dL) | 0.285 (0.1-9.24) | Not done |

| Bilirubin-unconjugated (mg/dL) | 0.34 (0.06-3.14) | Not done |

| SGOT (U/L) | 28.5 (10-1237) | 18 (15-36) |

| SGPT (U/L) | 22 (9-1731) | 16.5 (10-47) |

| Alk.Pho (U/L) | 91 (46-337) | Not done |

| Protein (total, g/dL) | 7 (3.9-8.9) | Not done |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.8 (1.8-6.3) | Not done |

| Globulin (g/dL) | 3.1 (1.7-5.3) | Not done |

| Albumin-globulin ratio | 1.24 (0.46-2.05) | Not done |

Out of the 100 HBsAg-positive individuals enrolled, 68 samples subjected to HBV DNA quantification. Among these, 17 individuals exhibited a viral load > 2000 IU/mL, 24 had < 2000 IU/mL, 11 were negative, 15 were invalid, and 1 was undetermined. The viral load distribution highlighted considerable heterogeneity in replication activity among the asymptomatic carriers. The lowest detectable viral load was 0.024 IU/mL, while the highest was 2033777.25 IU/mL.

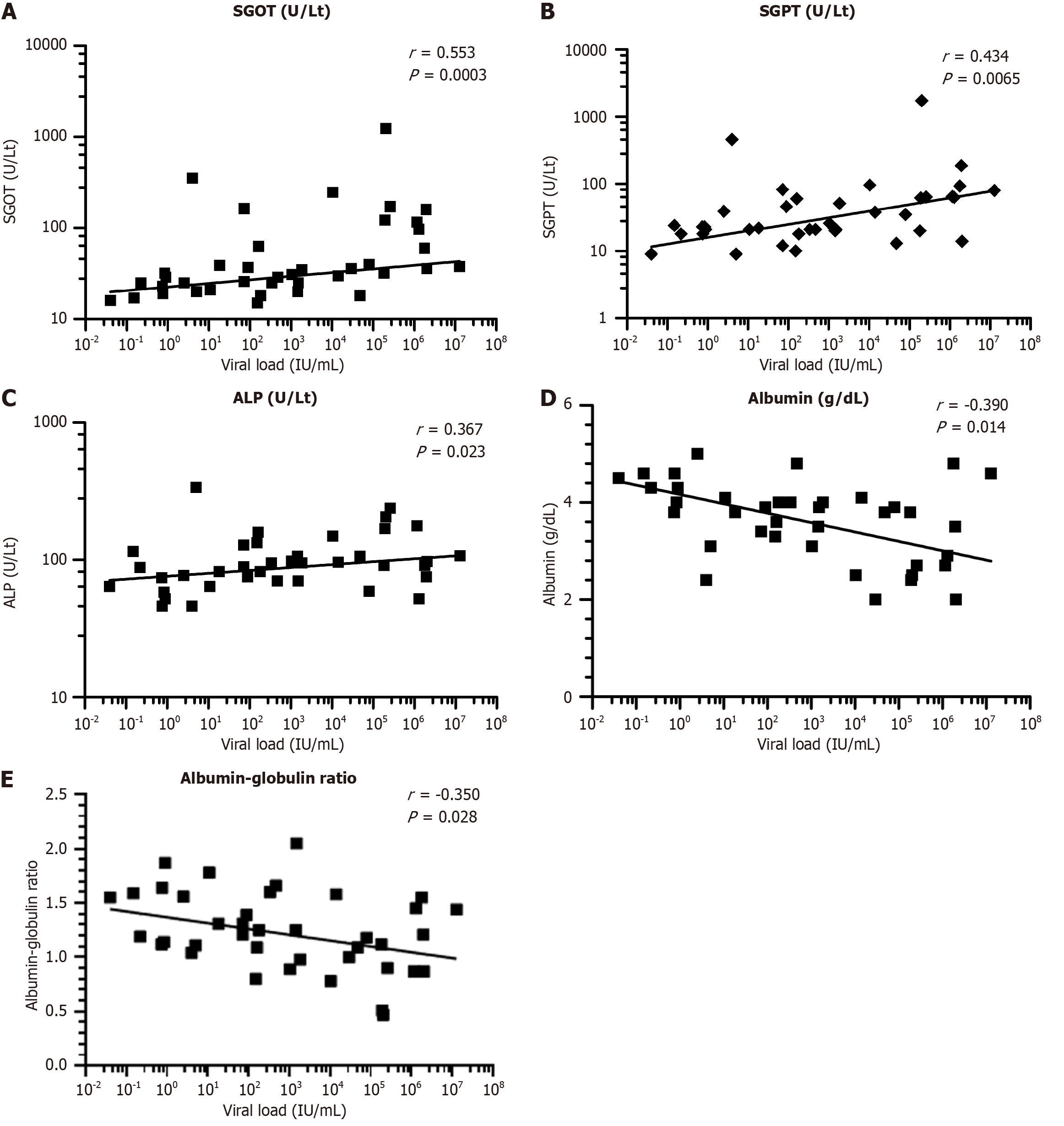

A statistical correlation assessment was performed to evaluate the relationship between HBV DNA concentration and key liver function indicators. The analysis revealed a moderately strong positive association between viral DNA levels and serum SGOT (r = 0.55, P < 0.0003), SGPT (r = 0.43, P < 0.0065), conjugated bilirubin (r = 0.58, P < 0.01), and ALP (r = 0.37, P < 0.0232). These results indicate that elevated viral replication is linked to increased hepatocellular and biliary tract injury. In contrast, viral load demonstrated a negative association with serum albumin (r = -0.39, P < 0.014) and the albumin-to-globulin ratio (r = -0.35, P < 0.029), suggesting that higher viral burden may correspond to diminished hepatic synthetic capacity (Figure 3).

The current study provides important insights into the haematological, biochemical, and virological characteristics of asymptomatic individuals diagnosed with HBsAg positivity, in comparison with healthy controls. Significant deviations were observed in their laboratory profiles, underscoring the subclinical impact of HBV infection.

The HBV cohort exhibited a mean age of around 40 years, reflecting earlier reports that middle-aged individuals in endemic areas are more frequently affected. A higher representation of males was noted, with a male-to-female ratio of approximately 1.8:1, which corresponds with epidemiological evidence indicating greater HBV occurrence and rep

Significant alterations in haematological parameters, especially reduced haemoglobin levels and a shift in leukocyte profiles were evident in the HBV group. Anaemia, as indicated by significantly lower haemoglobin concentrations (P < 0.0001), may be attributed to chronic inflammation or mild bone marrow suppression associated with HBV. The increase in neutrophil percentages and decrease in lymphocyte counts may reflect an ongoing inflammatory response and imm

Biochemical markers of liver injury were also significantly elevated in the HBV group. Increased serum transaminase levels (AST and ALT) suggest ongoing hepatocellular damage despite the asymptomatic presentation. This pattern is often observed in the immune-active phase of chronic HBV infection, which may progress silently over time. Inter

Quantitative assessment of HBV DNA revealed wide inter-individual variability in viral loads. Approximately 25% of the tested individuals had viral loads above 2000 IU/mL, a threshold often considered clinically significant for det

The correlation analysis further supports the relationship between viral replication and liver injury. There were notable positive correlations between HBV DNA levels and liver enzymes such as AST, ALT, and ALP, suggesting that higher viral loads are associated with greater hepatocellular and biliary injury. In contrast, negative correlations with serum albumin and albumin/globulin ratio indicate that increased viral activity may be associated with impaired protein syn

This study emphasizes the need for vigilant monitoring of asymptomatic HBV carriers. Despite the absence of clinical symptoms, a considerable proportion of these individuals exhibit laboratory evidence of hepatic inflammation and im

This study offers novel insight into HBV activity in asymptomatic individuals using hematological and biochemical parameters. The strength of the study lies in its well-characterized sample group and comprehensive laboratory-based evaluation, which allowed for detailed correlation between viral load and hepatic biomarkers. However, we also reco

This cross-sectional study highlights that asymptomatic individuals testing positive for HBsAg may still exhibit significant alterations in hematological and liver function parameters. Despite the absence of clinical symptoms, elevated levels of SGOT, ALT, and neutrophils, alongside decreased hemoglobin and lymphocyte counts, indicate an ongoing hepatic and immunological response. Moreover, wide variability in HBV DNA levels suggests differing degrees of viral replication, with a considerable subset of individuals exhibiting viral loads above the clinically significant threshold of 2000 IU/mL. Positive correlations between viral load and markers of hepatic injury, and negative correlations with albumin and albumin/globulin ratio, reinforce the impact of viral activity on liver function. These findings emphasize the need for routine laboratory monitoring in asymptomatic HBV carriers to enable early identification of disease pro

We thank the patients participated in the study. The authors are grateful to Dr. D. Y. Patil Medical College, Hospital and Research Centre and Dr. D. Y. Patil Vidyapeeth, Pune, for providing necessary facility and support.

| 1. | Hsu YC, Huang DQ, Nguyen MH. Global burden of hepatitis B virus: current status, missed opportunities and a call for action. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;20:524-537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 369] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Ratnaparkhi MM, Vyawahare CR, Gandham NR. Hepatitis B virus genotype distribution and mutation patterns: Insights and clinical implications for hepatitis B virus positive patients. World J Exp Med. 2025;15:102395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 3. | Alberts CJ, Clifford GM, Georges D, Negro F, Lesi OA, Hutin YJ, de Martel C. Worldwide prevalence of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus among patients with cirrhosis at country, region, and global levels: a systematic review. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:724-735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 37.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Al-Busafi SA, Alwassief A. Global Perspectives on the Hepatitis B Vaccination: Challenges, Achievements, and the Road to Elimination by 2030. Vaccines (Basel). 2024;12:288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Li P, Liu J, Li Y, Su J, Ma Z, Bramer WM, Cao W, de Man RA, Peppelenbosch MP, Pan Q. The global epidemiology of hepatitis E virus infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Liver Int. 2020;40:1516-1528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 32.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lim JK, Nguyen MH, Kim WR, Gish R, Perumalswami P, Jacobson IM. Prevalence of Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:1429-1438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Usuda D, Kaneoka Y, Ono R, Kato M, Sugawara Y, Shimizu R, Inami T, Nakajima E, Tsuge S, Sakurai R, Kawai K, Matsubara S, Tanaka R, Suzuki M, Shimozawa S, Hotchi Y, Osugi I, Katou R, Ito S, Mishima K, Kondo A, Mizuno K, Takami H, Komatsu T, Nomura T, Sugita M. Current perspectives of viral hepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30:2402-2417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 8. | Cao X, Wang Y, Li P, Huang W, Lu X, Lu H. HBV Reactivation During the Treatment of Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma and Management Strategies. Front Oncol. 2021;11:685706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Caserta S, Gangemi S, Murdaca G, Allegra A. Gender Differences and miRNAs Expression in Cancer: Implications on Prognosis and Susceptibility. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:11544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kramvis A, Chang KM, Dandri M, Farci P, Glebe D, Hu J, Janssen HLA, Lau DTY, Penicaud C, Pollicino T, Testoni B, Van Bömmel F, Andrisani O, Beumont-Mauviel M, Block TM, Chan HLY, Cloherty GA, Delaney WE, Geretti AM, Gehring A, Jackson K, Lenz O, Maini MK, Miller V, Protzer U, Yang JC, Yuen MF, Zoulim F, Revill PA. A roadmap for serum biomarkers for hepatitis B virus: current status and future outlook. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;19:727-745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 32.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Al Beloushi M, Saleh H, Ahmed B, Konje JC. Congenital and Perinatal Viral Infections: Consequences for the Mother and Fetus. Viruses. 2024;16:1698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bedi HK, Trasolini R, Lowe CF, Hussaini T, Bigham M, Ritchie G, Yoshida EM. De novo hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-positive, core antibody (anti-HBc)-negative, hepatitis B virus infection post-liver transplant from an anti-HBc, HBsAg-negative donor. Hepatol Forum. 2021;2:117-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zamor PJ, Lane AM. Interpretation of HBV Serologies. Clin Liver Dis. 2021;25:689-709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | de Almeida Pondé RA. Detection of the serological markers hepatitis B virus surface antigen (HBsAg) and hepatitis B core IgM antibody (anti-HBcIgM) in the diagnosis of acute hepatitis B virus infection after recent exposure. Microbiol Immunol. 2022;66:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhang Y, Zhu Y, Zhou Y, Tan Z, Dan Y, Zou X, Deng G, Tan W. Anti-HBc IgM associates with acute flare and HBeAg/HBsAg loss in chronic hepatitis B patients with acute exacerbation. Virulence. 2025;16:2534078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kalas MA, Chavez L, Leon M, Taweesedt PT, Surani S. Abnormal liver enzymes: A review for clinicians. World J Hepatol. 2021;13:1688-1698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 30.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (27)] |

| 17. | Khalifa A, Lewin DN, Sasso R, Rockey DC. The Utility of Liver Biopsy in the Evaluation of Liver Disease and Abnormal Liver Function Tests. Am J Clin Pathol. 2021;156:259-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yoshida K, Desbiolles A, Feldman SF, Ahn SH, Alidjinou EK, Atsukawa M, Bocket L, Brunetto MR, Buti M, Carey I, Caviglia GP, Chen EQ, Cornberg M, Enomoto M, Honda M, Zu Siederdissen CH, Ishigami M, Janssen HLA, Maasoumy B, Matsui T, Matsumoto A, Nishiguchi S, Riveiro-Barciela M, Takaki A, Tangkijvanich P, Toyoda H, van Campenhout MJH, Wang B, Wei L, Yang HI, Yano Y, Yatsuhashi H, Yuen MF, Tanaka E, Lemoine M, Tanaka Y, Shimakawa Y. Hepatitis B Core-Related Antigen to Indicate High Viral Load: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 10,397 Individual Participants. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:46-60.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Nyarko ENY, Obirikorang C, Owiredu WKBA, Adu EA, Acheampong E. Assessment of the performance of haematological and non-invasive fibrotic indices for the monitoring of chronic HBV infection: a pilot study in a Ghanaian population. BMC Res Notes. 2023;16:312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Khalid A, Ali Jaffar M, Khan T, Abbas Lail R, Ali S, Aktas G, Waris A, Javaid A, Ijaz N, Muhammad N. Hematological and biochemical parameters as diagnostic and prognostic markers in SARS-COV-2 infected patients of Pakistan: a retrospective comparative analysis. Hematology. 2021;26:529-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Athalye S, Khargekar N, Shinde S, Parmar T, Chavan S, Swamidurai G, Pujari V, Panale P, Koli P, Shankarkumar A, Banerjee A. Exploring risk factors and transmission dynamics of Hepatitis B infection among Indian families: Implications and perspective. J Infect Public Health. 2023;16:1109-1114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Im YR, Jagdish R, Leith D, Kim JU, Yoshida K, Majid A, Ge Y, Ndow G, Shimakawa Y, Lemoine M. Prevalence of occult hepatitis B virus infection in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:932-942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hong X, Luckenbaugh L, Perlman D, Revill PA, Wieland SF, Menne S, Hu J. Characterization and Application of Precore/Core-Related Antigens in Animal Models of Hepatitis B Virus Infection. Hepatology. 2021;74:99-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Cai J, Wu W, Wu J, Chen Z, Wu Z, Tang Y, Hu M. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of hepatitis B surface antigen-negative/hepatitis B core antibody-positive patients with detectable serum hepatitis B virus DNA. Ann Transl Med. 2022;10:25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Nita ME, Gaburo N Jr, Cheinquer H, L'Italien G, Affonso de Araujo ES, Mantilla P, Cure-Bolt N, Lotufo PA. Patterns of viral load in chronic hepatitis B patients in Brazil and their association with ALT levels and HBeAg status. Ann Hepatol. 2009;8:339-345. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Shao J, Wei L, Wang H, Sun Y, Zhang LF, Li J, Dong JQ. Relationship between hepatitis B virus DNA levels and liver histology in patients with chronic hepatitis B. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2104-2107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Wu Y, Wang X, Lin X, Shen C, Chen X. Quantitative of serum hepatitis B core antibody is a potential predictor of recurrence after interferon-induced hepatitis B surface antigen clearance. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2021;54:238-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Wang SJ, Chen ZM, Wei M, Liu JQ, Li ZL, Shi TS, Nian S, Fu R, Wu YT, Zhang YL, Wang YB, Zhang TY, Zhang J, Xiong JH, Tong SP, Ge SX, Yuan Q, Xia NS. Specific determination of hepatitis B e antigen by antibodies targeting precore unique epitope facilitates clinical diagnosis and drug evaluation against hepatitis B virus infection. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2021;10:37-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/