Published online Sep 27, 2025. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v17.i9.110162

Revised: June 27, 2025

Accepted: August 1, 2025

Published online: September 27, 2025

Processing time: 118 Days and 14.8 Hours

The trial by Cano Contreras et al examined a proprietary formulation containing Silybum marianum and alpha-lipoic acid (SM-ALA), combined with a Mediterranean diet, in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. While some metabolic benefits were observed, limitations such as the absence of an SM-ALA-only group, the lack of histological data, and a small sam

Core Tip: This commentary reviews a clinical trial that investigated the combination of silymarin and alpha-lipoic acid, along with a Mediterranean diet, in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Although some health improvements were noted, issues like small sample size, lack of a supplement-only group, and poor tracking of adherence make the results less reliable. The letter suggests future studies should use stronger designs, clear outcomes, balanced sex representation, and transparent reporting to improve the usefulness and accuracy of research findings.

- Citation: Martínez-Sánchez FD, Martínez-Vázquez SE, Gutiérrez-Monterrubio R, Muñoz-Martínez S, Garcia-Juarez I. Silymarin-alpha lipoic acid and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: Insights and methodological considerations. World J Hepatol 2025; 17(9): 110162

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v17/i9/110162.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v17.i9.110162

We read the recent article by Cano Contreras et al[1], published in the World Journal of Hepatology, with great interest. The article examines the effects of a combined supplement containing Silybum marianum (S. marianum) and alpha-lipoic acid (SM-ALA) along with a Mediterranean diet on patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). While the authors present potentially encouraging results, a closer evaluation of the study's methodology reveals several critical weaknesses that limit the validity, reliability, and clinical applicability of its conclusions.

This first study (a mixture of phase 1 and 2 clinical research) employed a randomized, double-blind design comparing SM-ALA, a formulation never studied before, plus a Mediterranean diet (intervention group) with placebo plus Mediterranean diet (control group) over 24 weeks. According to the authors, patients receiving SM-ALA experienced significant reductions in visceral fat, umbilical circumference (not a MeSH-recognized term), and liver fat content as measured by controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) via transient elastography[1]. Mild adverse events were reported similarly in both groups, suggesting good tolerability; however, adherence to either the diet or supplement was not reported.

The trial’s design makes it impossible to isolate the effects of SM-ALA from those of calorie restriction or the Mediterranean diet, both of which are independently known to improve insulin sensitivity, reduce intrahepatic lipid content, and decrease liver stiffness and body weight[2-5]. Previous clinical trials using alpha-lipoic acid or S. marianum alone have shown modest improvements in alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, insulin sensitivity, and hepatic fat content[6,7]. Due to the overlapping effects of dietary changes and supplementation, a third arm receiving SM-ALA without dietary intervention would have been necessary to identify the supplement’s specific impact. This design flaw introduces a major confounding factor that undermines internal validity.

Additionally, the study lacks histological confirmation of hepatic changes[8]. The authors relied solely on transient elastography to assess steatosis and stiffness. Although widely used, this method cannot capture the full histopathological spectrum of MASLD, including ballooning, inflammation, and fibrosis regression[9]. The current trend in MASLD studies is to implement non-invasive tools to replace the need for liver biopsy; however, these are still not widely acc

Another significant limitation is the small sample size and its calculation, which was based on a study that evaluated improvement only by ultrasound-graded steatosis. Although the trial was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT0

Additionally, the study population was predominantly female (74%), which may limit generalizability. Given sex-specific variations in visceral adiposity, hormonal influences, and differential responses to dietary and nutraceutical interventions, future trials should ensure balanced recruitment and consider sex-stratified analyses.

Moreover, the reliance on surrogate endpoints, such as visceral fat percentage and waist circumference (referred to as umbilical circumference), is problematic. These markers reflect body composition but do not directly translate into improved clinical outcomes. While CAP is commonly used to estimate liver steatosis, it lacks prognostic value and is susceptible to the “burn-out phenomenon” in advanced disease stages. In contrast, liver stiffness measurement correlates more closely with long-term clinical outcomes and fibrosis progression. CAP value reductions, while informative, lack correlation with patient-centered outcomes such as liver-related morbidity, health-related quality of life, or cirrhosis progression[9]. Furthermore, given the chronic and progressive nature of MASLD, future studies should incorporate long-term follow-up to evaluate sustained effects on fibrosis progression, liver-related events, and overall clinical outcomes, rather than relying solely on short-term metabolic improvements.

Dietary adherence assessment was also limited. All participants were instructed to follow a Mediterranean diet, central to the intervention’s potential effects. However, adherence was evaluated only through a self-reported tool, without objective verification such as dietary records, nutritional biomarkers, or third-party monitoring. This weakens comparability across groups and leaves room for significant interindividual variation in compliance[11].

Furthermore, the supplement tested is a proprietary product not widely available outside the country of origin. The authors disclose that the manufacturer provided the product, and at least one author declared a conflict of interest. Although transparency is acknowledged, the compound's proprietary nature limits the findings' external generalizability, particularly in regions where similar products may vary in composition or dosage[12]. Additionally, financial ties with the manufacturer may have influenced key aspects of the study design (including endpoint selection, emphasis on surrogate markers, and interpretation of results), which should be considered when evaluating the objectivity and applicability of the findings.

Given the absence of prior pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data for SM-ALA, phase I trials are essential to establish safety, optimal dosing, and bioavailability. Without early-phase evidence, the interpretation of efficacy signals in phase II or III studies remains limited. Regulatory standards for drug development support this sequential approach, especially when nutraceuticals are proposed for disease modification.

Designing a clinical trial in nutrition requires specific considerations due to numerous lifestyle-related confounding factors. Unlike pharmacologic agents, diets cannot be blinded, and adherence is heavily influenced by culture, access, and personal preferences. Therefore, meticulous supervision and measurement of dietary adherence are essential to avoid false positives or misinterpretation of outcomes[13]. Although designing adequate placebos for nutraceuticals, such as ALA, can be challenging due to their organoleptic and physicochemical properties, it is possible to conduct transparent and reproducible interventions[14].

Moreover, promoting adherence to a diet that is not culturally or geographically typical for the population may result in lower compliance. When a supplement with only mild expected benefits is added to such a dietary pattern, the risk of overestimating its clinical impact increases. A rigorous trial design must account for these limitations to ensure reliable conclusions. It is also important to acknowledge that dietary intervention trials face unique challenges distinct from those of pharmacologic studies, including variable adherence, cultural acceptability, and difficulties in designing placebos. Future research should consider incorporating culturally adapted dietary patterns, employing validated patient-reported outcomes, and using composite clinical endpoints to capture subjective and objective benefits better.

Another important thing missing was an explanation of why the specific dosage of SM-ALA was chosen. Although the product is commercially available, there are no pharmacokinetic, dose-response, or phase I trial data to support the chosen dose. This raises questions about whether the intervention was effective or not. In addition, although the authors provide results for each group separately, they don't present a structured between-group comparison (SM-ALA + mediterranean diet vs placebo + mediterranean diet). There are some between-group P-values cited, but the paper doesn't provide enough information about whether the changes in critical parameters, such as visceral fat, CAP, or inflammatory markers, were significantly greater in the intervention group than in the control group. Because of this, it's difficult to determine how much more SM-ALA helps than just a diet. A full head-to-head comparison, including effect sizes and co

From a design standpoint, we recommend that future trials include three parallel arms: SM-ALA plus Mediterranean diet, SM-ALA alone, and Mediterranean diet alone. This design would enable more accurate attribution of effects to each component. Additionally, validated non-invasive tools such as magnetic resonance imaging-proton density fat fraction or the enhanced liver fibrosis score should be considered primary endpoints when liver biopsy is not feasible[15,16]. Recent evidence further emphasizes the need for rigorous trial design in nutraceutical research. A recent meta-analysis con

To strengthen adherence measurement in future trials, we suggest combining self-reported data with objective methods such as plasma carotenoid levels, digital food photography applications, or third-party assessments, as these strategies have demonstrated improved reliability in dietary studies. Furthermore, the use of wearable devices or mobile applications for real-time tracking may help reduce recall bias and enhance data accuracy. In parallel, supplement adherence was monitored only via phone follow-up; future studies should incorporate structured verification tools, such as pill counts, serum drug levels, or validated compliance biomarkers, to ensure accurate interpretation of intervention effects. To assist researchers in designing robust future trials, we summarize key methodological considerations for nutraceutical-based MASLD interventions in Table 1.

| Domain | Recommendation |

| Trial arms | Include three arms: SM-ALA + diet, SM-ALA only, and diet only |

| Primary outcomes | Use validated non-invasive endpoints (e.g., MRI-PDFF, ELF score) |

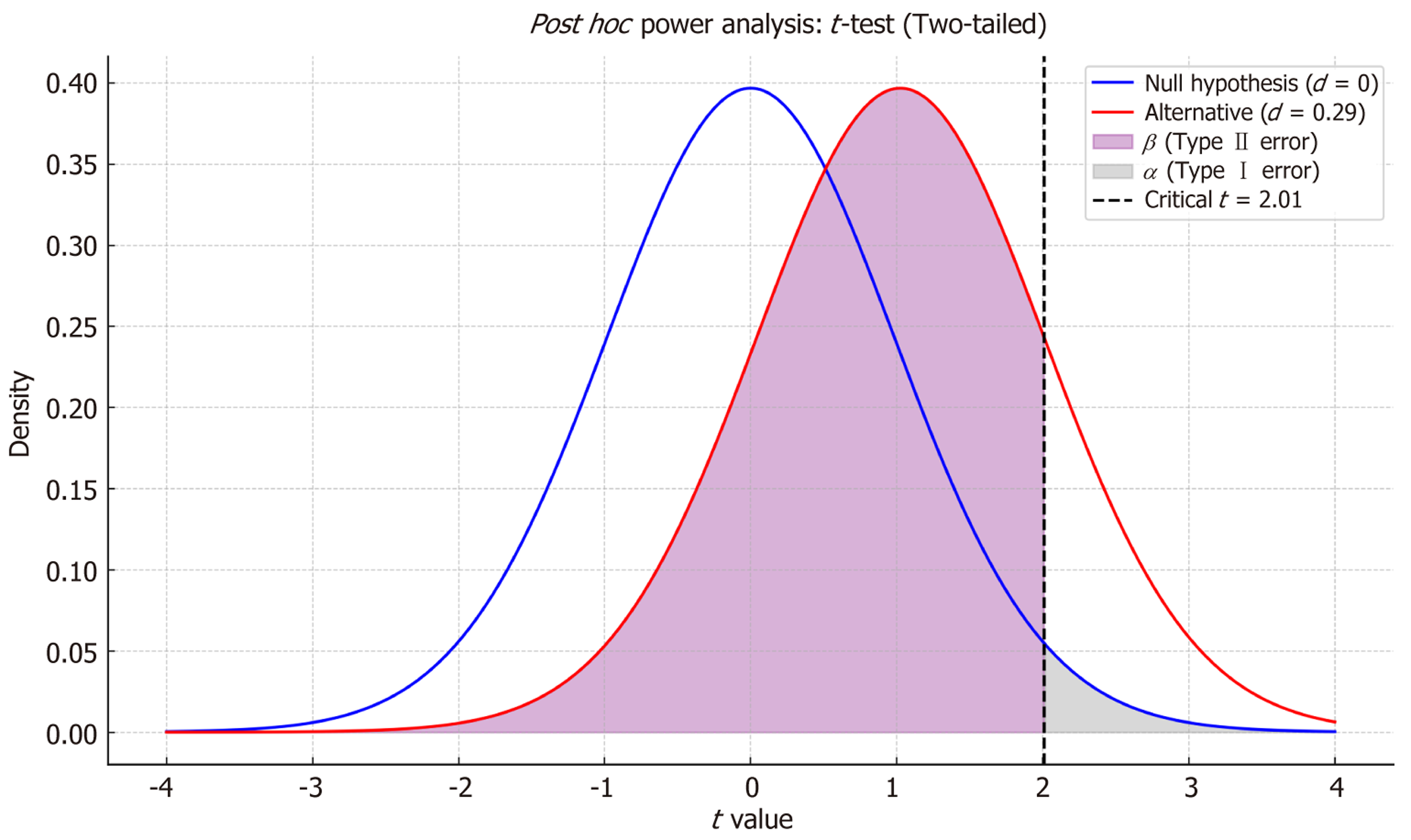

| Sample size | Perform power analysis; consider adaptive designs with interim analyses |

| Adherence monitoring | Combine self-report with biomarkers (e.g., plasma carotenoids), apps, third-party |

| Regulatory considerations | Include early-phase PK/PD and safety data (phase I) before efficacy claims |

| Mechanistic support | Provide preclinical or translational evidence on SM-ALA’s pathways |

| Reporting transparency | Follow CONSORT and report manufacturer involvement and conflicts of interest |

The authors made a commendable effort in presenting a clinical trial evaluating a nutraceutical-based intervention for MASLD[1], a condition of increasing global prevalence and a leading cause of cirrhosis worldwide[18]. As the burden of MASLD continues to rise, such research initiatives are valuable and much needed. Nevertheless, significant methodological constraints, including the lack of a supplement-only control group, the absence of histological validation, a limited sample size, and insufficient evaluation of dietary adherence, necessitate careful interpretation of the results. Future clinical trials must employ rigorous designs that differentiate the impacts of each intervention component, utilize proven clinical outcomes, and ensure cultural and nutritional relevance. Transparent reporting and accessible treatments are essential for enhancing repeatability, external validity, and informing therapeutic practice. Public registries of proprietary supplement compositions could also be encouraged to enhance transparency and reproducibility. Future clinical trials should incorporate three-arm designs, objective adherence metrics, validated non-invasive endpoints, and include pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic exploration to define optimal dosing strategies. In addition, positioning SM-ALA within current MASLD treatment paradigms requires evidence of safety and biochemical efficacy and long-term benefits on fibrosis progression, which remains to be demonstrated.

| 1. | Cano Contreras AD, Del Rocío Francisco M, Vargas Basurto JL, Gonzalez-Gomez KD, Amieva-Balmori M, Roesch Dietlen F, Remes-Troche JM. Effect of alpha-lipoic acid and Silybum marianum supplementation with a Mediterranean diet on metabolic dysfunction-associated steatosis. World J Hepatol. 2025;17:101704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Zelber-Sagi S, Salomone F, Mlynarsky L. The Mediterranean dietary pattern as the diet of choice for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Evidence and plausible mechanisms. Liver Int. 2017;37:936-949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Houttu V, Csader S, Nieuwdorp M, Holleboom AG, Schwab U. Dietary Interventions in Patients With Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Nutr. 2021;8:716783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Del Bo' C, Perna S, Allehdan S, Rafique A, Saad S, AlGhareeb F, Rondanelli M, Tayyem RF, Marino M, Martini D, Riso P. Does the Mediterranean Diet Have Any Effect on Lipid Profile, Central Obesity and Liver Enzymes in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) Subjects? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Control Trials. Nutrients. 2023;15:2250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dobbie LJ, Burgess J, Hamid A, Nevitt SJ, Hydes TJ, Alam U, Cuthbertson DJ. Effect of a Low-Calorie Dietary Intervention on Liver Health and Body Weight in Adults with Metabolic-Dysfunction Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD) and Overweight/Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2024;16:1030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Li BY, Xi Y, Liu YP, Wang D, Wang C, Chen CG, Fang XH, Li ZX, Chen YM. Effects of Silybum marianum, Pueraria lobate, combined with Salvia miltiorrhiza tablets on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in adults: A triple-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2024;63:2-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shaker MK, Hassany M, Eysa B, Adel A, Zidan A, Mohamed S. The activity of a herbal medicinal product of Phyllanthus niruri and Silybum marianum powdered extracts (Heptex®) in patients with apparent risk factors for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a phase II, multicentered, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2025;25:8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wong VW, Vergniol J, Wong GL, Foucher J, Chan HL, Le Bail B, Choi PC, Kowo M, Chan AW, Merrouche W, Sung JJ, de Lédinghen V. Diagnosis of fibrosis and cirrhosis using liver stiffness measurement in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;51:454-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 876] [Cited by in RCA: 984] [Article Influence: 61.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Caldwell SH. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: summary of an AASLD Single Topic Conference. Hepatology. 2003;37:1202-1219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1488] [Cited by in RCA: 1486] [Article Influence: 64.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kang H. Sample size determination and power analysis using the G*Power software. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2021;18:17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 1120] [Article Influence: 224.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hamel V, Mialon M, Moubarac JC. 'The company is using the credibility of our profession': exploring experiences and perspectives of registered dietitians from Canada about their interactions with commercial actors using semi-structured interviews. Public Health Nutr. 2024;27:e196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ioannidis JPA, Trepanowski JF. Disclosures in Nutrition Research: Why It Is Different. JAMA. 2018;319:547-548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mirmiran P, Bahadoran Z, Gaeini Z. Common Limitations and Challenges of Dietary Clinical Trials for Translation into Clinical Practices. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2021;19:e108170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Medina-Urrutia AX, Jorge-Galarza E, El Hafidi M, Reyes-Barrera J, Páez-Arenas A, Masso-Rojas FA, Martínez-Sánchez FD, López-Uribe ÁR, González-Salazar MDC, Torres-Tamayo M, Juárez-Rojas JG. Effect of dietary chia supplementation on glucose metabolism and adipose tissue function markers in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease subjects. Nutr Hosp. 2022;39:1280-1288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lichtinghagen R, Pietsch D, Bantel H, Manns MP, Brand K, Bahr MJ. The Enhanced Liver Fibrosis (ELF) score: normal values, influence factors and proposed cut-off values. J Hepatol. 2013;59:236-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 276] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (10)] |

| 16. | Jia S, Zhao Y, Liu J, Guo X, Chen M, Zhou S, Zhou J. Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Proton Density Fat Fraction vs. Transient Elastography-Controlled Attenuation Parameter in Diagnosing Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children and Adolescents: A Meta-Analysis of Diagnostic Accuracy. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:784221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Shahsavari K, Ardekani SS, Ardekani MRS, Esfahani MM, Kazemizadeh H, Jamialahmadi T, Iranshahi M, Khanavi M, Hasanpour M. Are alterations needed in Silybum marianum (Silymarin) administration practices? A novel outlook and meta-analysis on randomized trials targeting liver injury. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2025;25:134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Martínez-Sánchez FD, Corredor-Nassar MJ, Feria-Agudelo SM, Paz-Zarza VM, Martinez-Perez C, Diaz-Jarquin A, Manzo-Santana F, Sánchez-Gómez VA, Rosales-Padron A, Baca-García M, Mejía-Ramírez J, García-Juárez I, Higuera-de la Tijera F, Pérez-Hernandez JL, Barranco-Fragoso B, Méndez-Sánchez N, Córdova-Gallardo J. Factors Associated With Advanced Liver Fibrosis in a Population With Type 2 Diabetes: A Multicentric Study in Mexico City. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2025;15:102536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/