Published online Mar 27, 2025. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v17.i3.104520

Revised: February 24, 2025

Accepted: March 6, 2025

Published online: March 27, 2025

Processing time: 92 Days and 16.2 Hours

High levels of acetaminophen (APAP) consumption can result in significant liver toxicity. Mogroside V (MV) is a bioactive, plant-derived triterpenoid known for its various pharmacological activities. However, the impact of MV on acute liver injury (ALI) is unknown.

To investigate the hepatoprotective potential of MV against liver damage caused by APAP and to examine the underlying mechanisms.

Mice were divided into three groups: Saline, APAP and APAP + MV. MV (10 mg/kg) was given intraperitoneally one hour before APAP (300 mg/kg) administration. Twenty-four hours after APAP exposure, serum transaminase levels, liver necrotic area, inflammatory responses, nitrotyrosine accumulation, and c-jun-N-terminal kinase (JNK) activation were assessed. Additionally, we analyzed reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, JNK activation, and cell death in alpha mouse liver 12 (AML12) cells.

MV pre-treatment in vivo led to a reduction in the rise of aspartate transaminase and alanine transaminase levels, mitigated liver damage, decreased nitrotyrosine accumulation, and blocked JNK phosphorylation resulting from APAP exposure, without affecting glutathione production. Similarly, MV diminished the APAP-induced increase in ROS, JNK phosphorylation, and cell death in vitro.

Our study suggests that MV treatment alleviates APAP-induced ALI by reducing ROS and JNK activation.

Core Tip: This study examines whether mogroside V (MV), a plant-derived triterpenoid, can mitigate acetaminophen (APAP)-induced acute liver injury (ALI). Both animal and cell experiments demonstrate that MV alleviates APAP-induced ALI by suppressing reactive oxygen species/c-jun-N-terminal kinase signaling independent of glutathione modulation. Our findings suggest that MV could serve as a potential prophylactic agent to prevent APAP-induced ALI.

- Citation: Shi JL, Sun T, Li Q, Li CM, Jin JF, Zhang C. Mogroside V protects against acetaminophen-induced liver injury by reducing reactive oxygen species and c-jun-N-terminal kinase activation in mice. World J Hepatol 2025; 17(3): 104520

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v17/i3/104520.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v17.i3.104520

Acetaminophen (APAP) is a commonly used medication known for its analgesic and antipyretic properties. However, excessive intake-whether due to drug abuse or accidental overdose-can lead to serious adverse effects, such as acute liver injury (ALI) and liver failure[1]. The liver, which serves as the main organ for detoxification processes, is especially susceptible to drug exposure. When hepatocytes are exposed to acute excess APAP, the drug undergoes metabolism through cytochrome P450 (CYP450), resulting in the production of significant amounts of the harmful metabolite N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI). This toxic compound rapidly reduces glutathione (GSH) within hepatocytes. Accumulation of NAPQI, when GSH is insufficient for detoxification, leads to its reaction with cysteine residues in proteins, ultimately resulting in hepatocyte necrosis[2]. While numerous studies have elucidated the pathogenesis of liver injury associated with APAP overdose[3,4], the development of effective therapeutic interventions remains limited[5]. Although the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine, a precursor of GSH, is currently recognized as an effective therapeutic agent, its efficacy is greatest when administered within 8 to 10 hours following APAP overdose, with therapeutic effects diminishing significantly if administration is delayed[6,7]. Consequently, there is a pressing need for further research into preventive measures and effective antidotes for APAP toxicity.

In recent years, the evaluation of bioactivity in antioxidants derived from natural sources has been extensively explored, revealing unexpected therapeutic effects[8]. Siraitia grosvenorii, commonly known as Monk fruit, is a tra

This study examines the hepatoprotective properties of MV in the context of ALI induced by APAP. The findings suggest that MV could serve as a promising therapeutic candidate for preventing ALI due to APAP exposure.

The MV powder, with a purity of at least 98%, was sourced from Chengdu Must Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Chengdu, China). The APAP powder (purity > 99.98%) was obtained from MCE Co., Ltd (HY-66005, China).

The alpha mouse liver 12 (AML12) cells were cultivated in DMEM/F-12 medium enriched with 5% FBS, dexa

Male C57BL/6J mice aged six to eight weeks were acquired from Jiangsu Huachuang Xinnuo Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd. (Jiangsu, China). The mice were housed in a SPF environment and had unlimited access to food, water, and rest. According to the previously reported method[18], an overdose of APAP was used to establish an ALI model by injecting of APAP (300 mg/kg) or vehicle (warm sterile saline) intraperitoneally to the mice that had undergone a 15-hour water-only fasting period.

Prior to the experiment, the mice were randomly assigned to three groups: Saline, APAP and APAP + MV. To examine the protective efficacy of multiple vs single administrations of MV against APAP-induced liver injury, we conducted two separate experiments: (1) In the experiment involving seven consecutive days of MV administrations, mice in the APAP + MV group received MV solution (10 mg/kg) via oral gavage once daily for seven consecutive days[19], after which APAP was administered one hour after the last dose of MV; and (2) In the single dose MV administration experiment, mice in the APAP + MV group received a single dose of MV solution (10 mg/kg) via oral gavage, followed by APAP administration one hour later. Finally, both serum and liver tissues from all mice were collected at specified time points after the injection of APAP.

The serum levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were measured using the mouse ALT ELISA kit and the mouse AST ELISA kit, respectively. The kits were obtained from Wuhan Sailuofei Biotechnology Co., Ltd., (Wuhan, China) and the procedure was performed according to the kit instructions.

Fresh liver tissues were fixed in 4% formaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, sliced into 4 μm thick sections, and dewaxed with turpentine for subsequent use. For Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, the sections were treated sequentially with eosin and hematoxylin. For immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining, the sections were soaked in 3% H2O2 to eliminate endogenous peroxide, followed by microwave heating. The sections were then incubated overnight at 4 ℃ with anti-Nitrotyrosine (Invitrogen, A-21285), anti-CD68 (Abcam, ab283654) or anti-S100A9 (Abcam, ab242945), and subsequently incubated with secondary antibodies for one hour at 37 ℃. Finally, the sections were stained with the DAB substrate kit (CST, 8059S) and hematoxylin in turn. For TUNEL staining, the Fluorescein (FITC) Tunel Cell Apoptosis Detection Kit (Servicebio, China) was utilized as per the manufacturer's protocol. The stained sections were examined and pho

GSH was measured using the Reduced GSH Assay kit (Solarbio, BC1175). In brief, liver tissue was homogenized in GSH assay lysis buffer. The lysate supernatant was used to detect GSH activity, according to the kit instructions.

The levels of target proteins in the samples were assessed by western blotting. Total protein lysate was collected after lysing liver tissues or cells and were subsequently subjected to denaturation. Equal amounts of protein lysate were placed onto 4%-20% SDS-PAGE gels (Beijing Tsingke Biotech Co., Ltd.) for separation, followed by transfer to 0.22 μm PVDF membranes. The membranes were then blocked using a blocking buffer, followed by incubation overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies: Anti- c-jun-N-terminal kinase (JNK) (CST), anti-p-JNK (CST), or anti-β-actin (Be

The intensity of the image signal was measured using ImageJ software. The results are presented as mean ± SEM. To assess statistical significance between the groups, a two-tailed unpaired student’s t test was employed, and comparisons across multiple groups were performed using Ordinary one-way ANOVA. All analyses were carried out with GraphPad Prism software, and a P value of less than 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

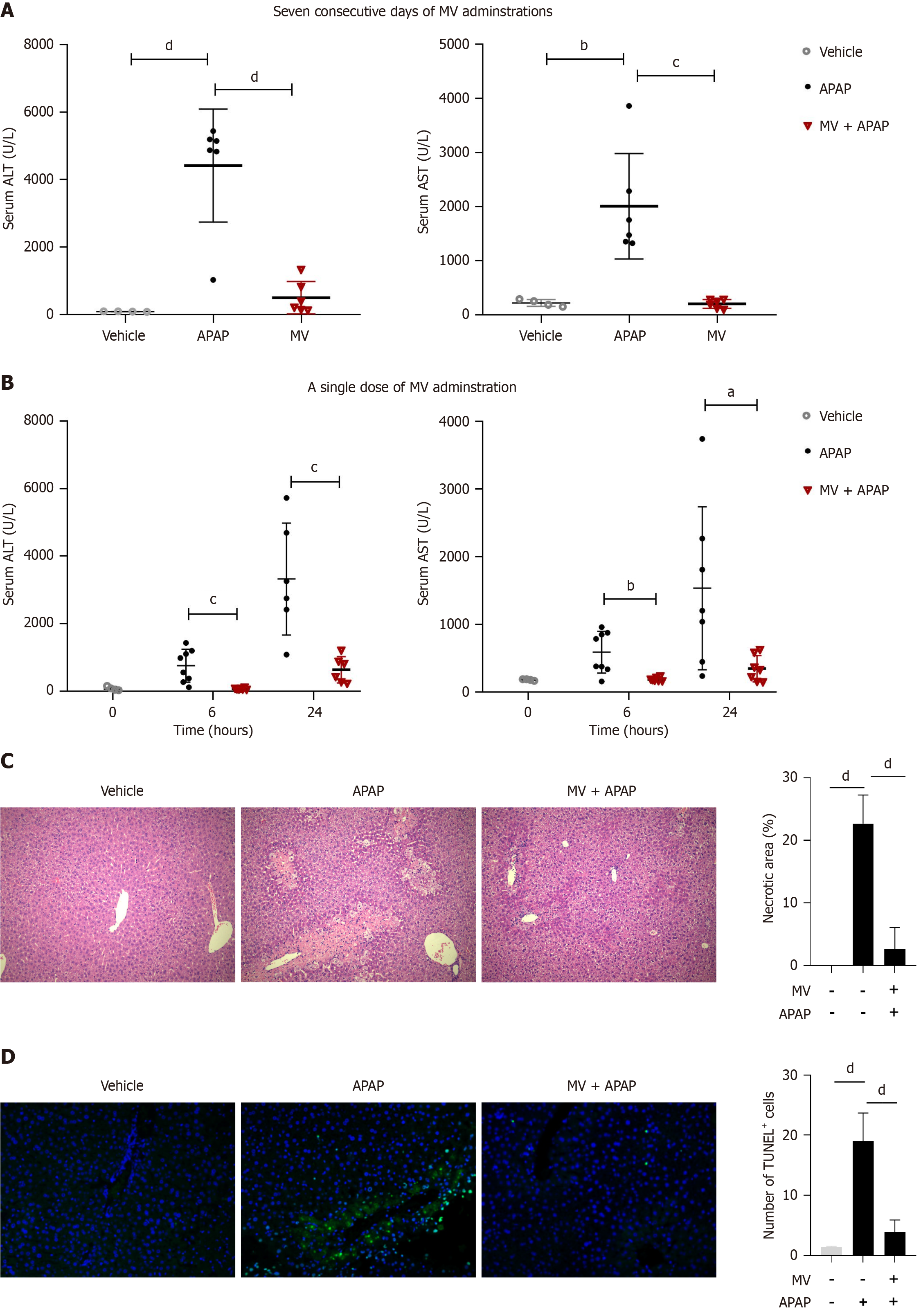

We initially evaluated the impact of oral MV administration over seven consecutive days on APAP-induced liver injury. As anticipated, the serum ALT and AST levels in APAP-treated mice exhibited a marked increase 24 hours post-APAP injection (Figure 1A). However, the elevation in serum ALT and AST levels induced by APAP was significantly mitigated following seven consecutive days of MV administration (Figure 1A). Notably, a single oral administration of MV one hour prior to APAP administration also significantly lowered the serum ALT and AST levels caused by APAP (Figure 1B). Consequently, the single-dose MV administration method was utilized in subsequent experiments. Additionally, we conducted H&E and TUNEL staining to assess the extent of liver damage. As illustrated in Figure 1C and D, the livers of mice in the APAP group exhibited extensive centrilobular necrosis and a substantial number of TUNEL+ cells. In contrast, the livers of mice in the MV + APAP group displayed only mild hepatocyte injury and a reduced number of TUNEL+ cells (Figure 1C and D). These results indicate that pre-treatment with MV can significantly improve APAP-induced ALI.

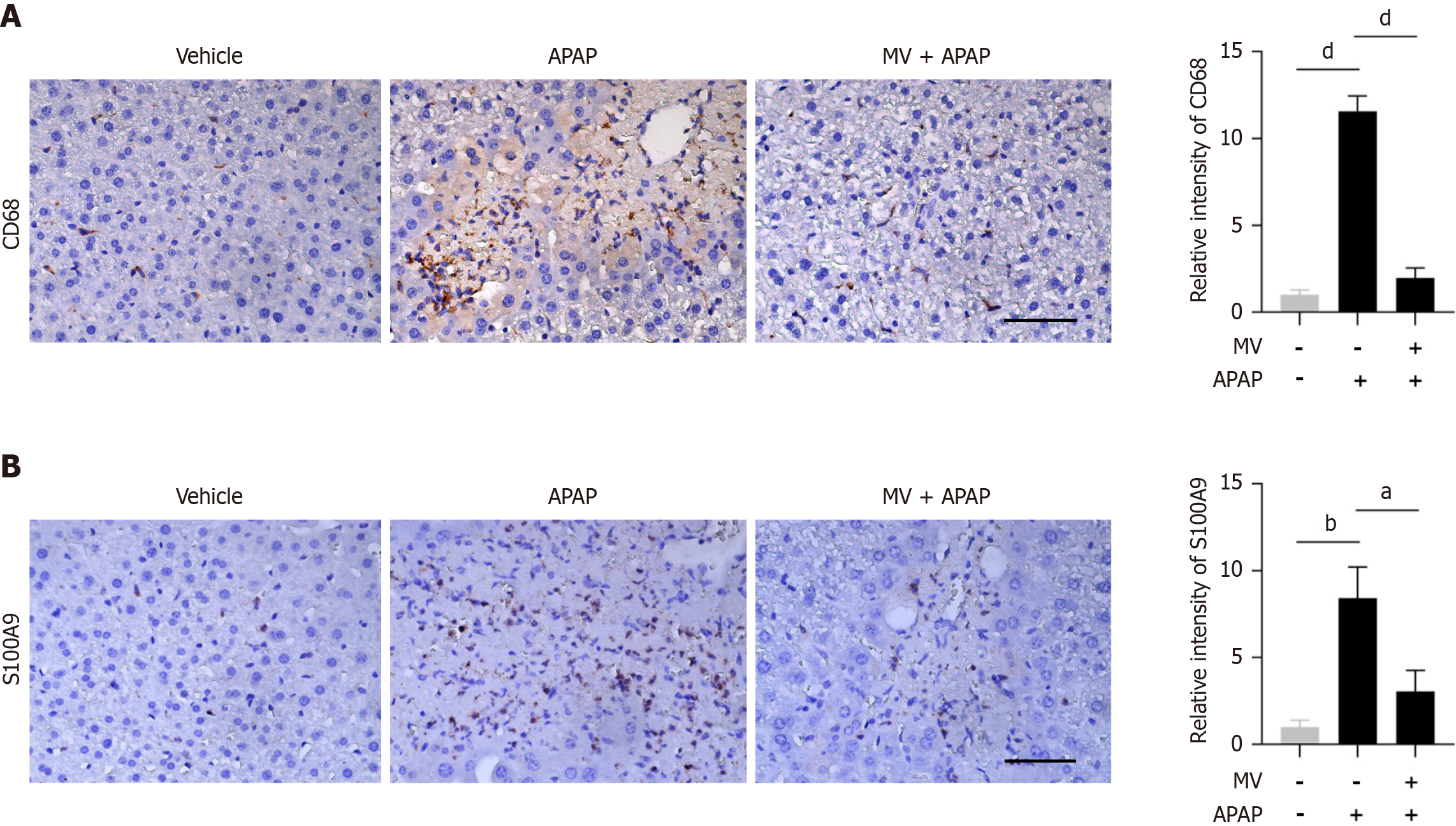

As a central immunological organ, the liver can rapidly initiate the immune system’s response to pathogens, infections, harmful stimuli or inflammation[20]. The calcium-binding protein S100A9 is intensely upregulated during inflammatory processes, and has been recognized as a biomarker for diagnosing inflammation-related diseases[21]. In order to explore the effect of MV on APAP-induced inflammatory responses, we assessed the presence of S100A9+ cells and macrophages (CD68+ cells) in the liver using IHC staining. As illustrated in Figure 2A, CD68+ macrophages were enriched in the injured area of the APAP-treated mice. Conversely, MV pre-treatment decreased the number of CD68+ macrophages in the liver of APAP-treated mice (Figure 2A). Similarly, the MV + APAP group exhibited a notable decrease in the amount of S100A9+ cells when compared to the APAP group (Figure 2B). Collectively, these findings indicate that MV pre-treatment significantly reduces both the recruitment of S100A9+ cells and CD68+ macrophages to the injured area, suggesting that MV alleviates the inflammatory response in the liver of APAP-induced ALI.

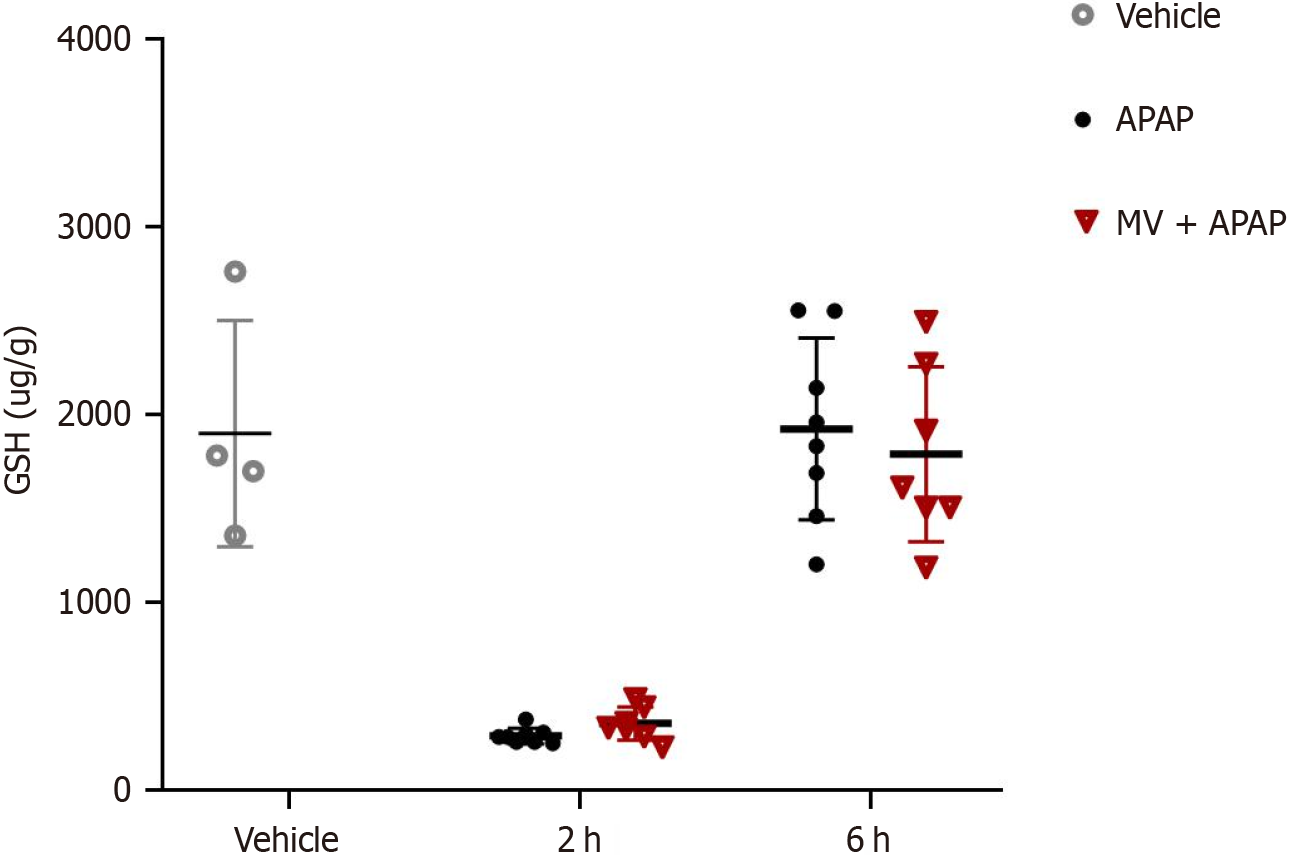

Given that GSH is a vital molecule involved in APAP poisoning, we examined the impact of MV on GSH levels. Two hours post-APAP poisoning, the GSH levels in the liver were significantly lower in mice treated with APAP; however, six hours later, these returned to baseline levels (Figure 3). Notably, the changes in GSH levels over time did not reveal any significant differences between the MV+APAP group and the APAP-only group. These results suggest that MV does not influence GSH depletion during APAP exposure.

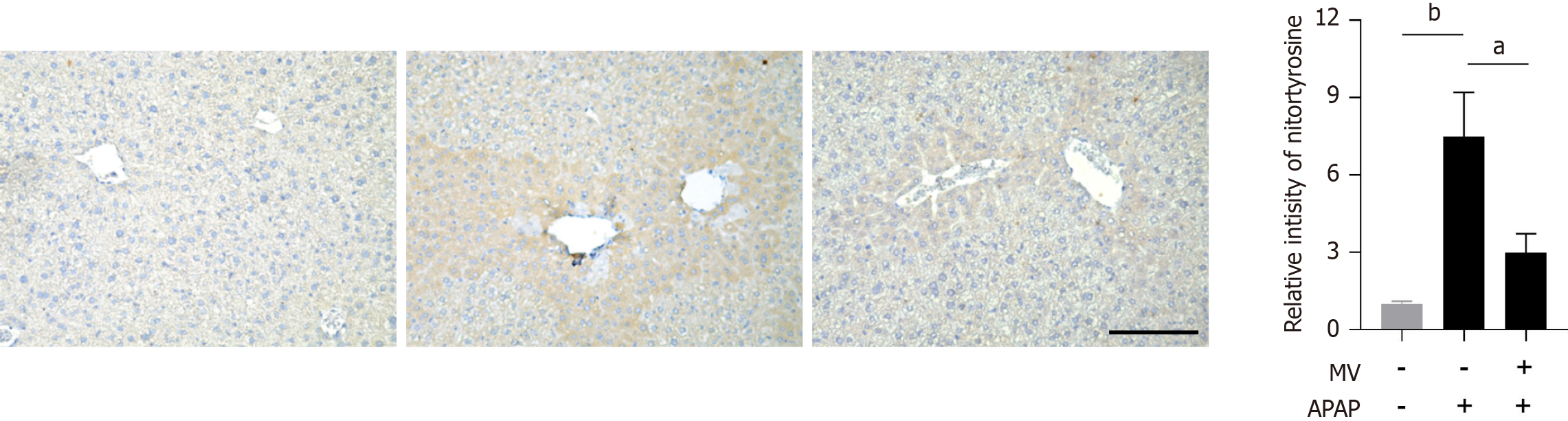

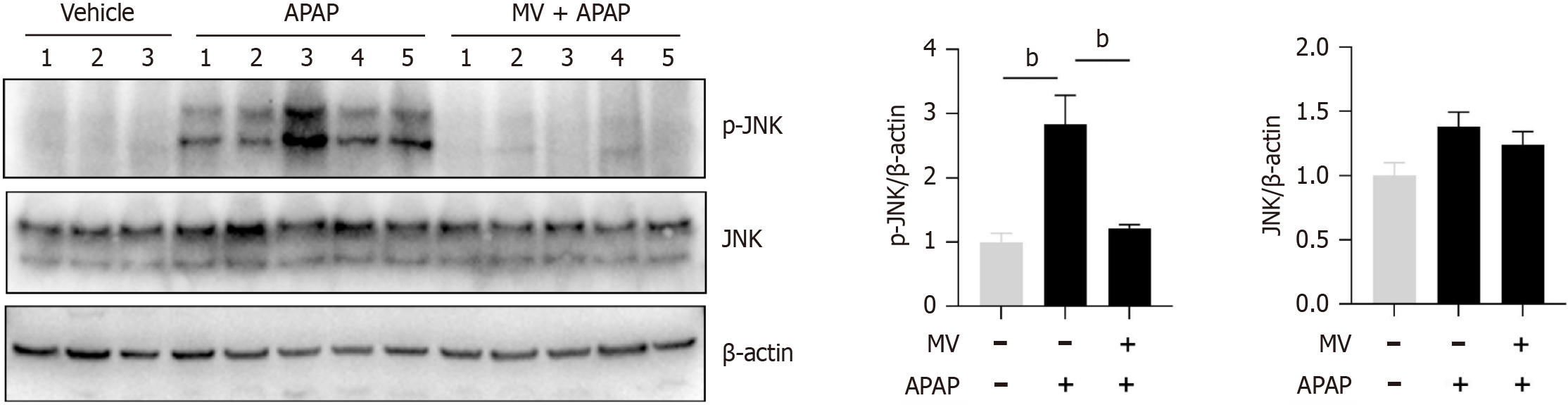

The activation of JNK is crucial for hepatocyte necrosis induced by APAP. We subsequently investigated whether MV affected JNK activation in the liver post-APAP treatment. The levels of p-JNK were found to be considerably increased in the liver of mice treated with APAP (Figure 4). However, MV pre-treatment markedly inhibited JNK activation (Figure 4). Given that MV contains several hydroxyl groups with antioxidant properties, we investigated the effect of MV on reactive oxygen species (ROS) production by APAP by assessing nitrotyrosine (the product of a type of ROS) levels using IHC staining. Nitrotyrosine was predominantly and abundantly expressed in the necrotic areas adjacent to the central vein in the livers of the APAP group (Figure 5). Notably, the nitrotyrosine levels in the MV+APAP group were significantly lower compared to those in the APAP group. These results suggest that MV pre-treatment can inhibit JNK activation by reducing ROS accumulation in the necrotic areas of mice treated with APAP.

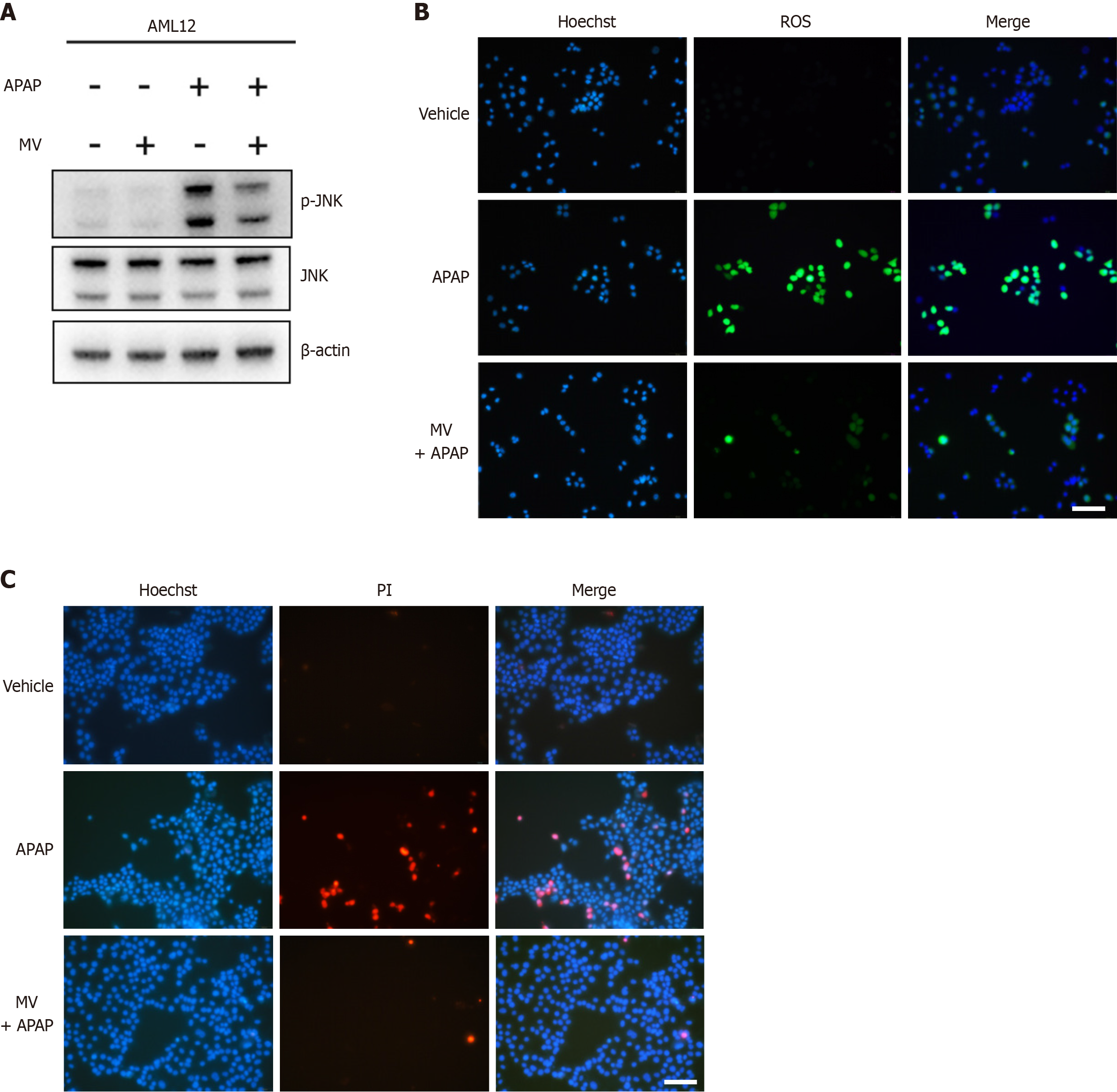

We further utilized the mouse hepatocytes AML12 Line to evaluate the impact of MV on APAP-induced hepatocyte damage. As expected, MV mitigated APAP-induced phosphorylation of JNK (Figure 6A). ROS are known to activate JNK in APAP-induced ALI; therefore, we used the H2DCFDH fluorescence probe to measure the effect of MV on ROS production in AML12 cells. Intracellular ROS accumulation significantly increased following APAP stimulation (Figure 6B). Notably, MV alleviated this accumulation (Figure 6B). Furthermore, PI staining revealed that MV inhibited APAP-induced cell death in AML12 hepatocytes (Figure 6C). These findings further support the idea that MV may protect against APAP-induced hepatocyte damage through diminishing ROS production and subsequent JNK activation.

In the current research, we performed a preventive intervention by administering MV solution via oral gavage to assess, for the first time, MV's protective role against APAP-induced ALI. The findings revealed that mice pretreated with MV showed significant resistance to APAP-induced ALI, which was linked to a reduction in ROS production and JNK activation.

APAP-induced ALI is characterized by the production of NAPQI, depletion of GSH, formation of mitochondrial protein adducts, generation of ROS, JNK activation, and mitochondrial dysfunction, ultimately culminating in hepatocyte necrosis and sterile inflammation. In our investigation, both the seven-day consecutive treatment and the single dose of MV substantially mitigated APAP-induced ALI, as indicated by lower serum levels of ALT and AST, fewer dead cells, reduced necrotic areas, and less inflammatory cell infiltration in the liver. It is well established that the toxic metabolite NAPQI can react with intracellular GSH during the initial phase of APAP exposure, resulting in a rapid depletion of GSH levels within two hours, subsequently intracellular GSH gradually returns to the initial levels[22,23]. Notably, MV pre-treatment did not alter GSH levels at either two or six hours after APAP exposure, suggesting that MV's protective effect is not linked to the metabolic process involving intracellular GSH consumption triggered by NAPQI.

Activation of JNK is essential in the response to cellular stress; however, persistent activation may result in cellular damage and necrosis. It is widely accepted that JNK activation is critical in the context of APAP-induced ALI, and the inhibition of JNK activation has been demonstrated to prevent APAP-induced ALI[24,25]. Additionally, diacerein offers protection against APAP-related injury by blocking JNK-driven oxidative stress and apoptosis[26]. Importantly, our findings suggest that MV treatment can considerably reduce the sustained JNK activation triggered by APAP exposure.

ROS is an important biomarker of oxidative stress with high biological activity. In hepatocytes after APAP exposure, NAPQI protein adducts form on mitochondria, initiating the opening of mitochondrial membrane permeability transition pores. This process leads to mitochondria oxidative stress and dysfunction, subsequently generating substantial amounts of ROS[2]. ROS has been identified as activators of the intracellular JNK pathway[27]. Thus, JNK activation and ROS production mutually enhance each other and contribute to APAP-induced necrosis in hepatocytes. A previous investigation demonstrated that MV could lower intracellular ROS levels and enhanced the expression of genes associated with oxidative stress in an in vitro porcine oocyte culture model[28]. Given that MV contains several hydroxyl groups with antioxidant properties, it is highly plausible that the bioactivity of MV is intricately linked to ROS in the context of APAP poisoning. To verify this hypothesis, we investigated whether MV could reduce ROS levels following APAP exposure. Our findings confirm that MV significantly decreased intracellular ROS levels in AML12 cells subjected to APAP exposure. In addition to MV, polysaccharides from Dendrobium officinale[29] and a phytoextract of Indian mustard seeds[30], have also been found to alleviate APAP-induced liver toxicity, presumably by decreasing ROS levels.

Nitrotyrosine is produced when protein tyrosine residues undergo nitration by the peroxynitrite anion, and its levels are frequently used as an indicator of ROS levels[31]. Nitration of proteins at the subcellular level can impair their normal conformation and physiological function to some extent[32]. This tyrosine nitration caused by peroxynitrite affects various active molecules in the body, including lipids, proteins and DNA, thereby contributing to disease progression. Previous studies have documented the accumulation of nitrotyrosine in conditions such as inflammation[33], acute lung injury[34], neurodegenerative diseases[35] and other pathological processes. Through IHC staining, we observed a notable accumulation of toxic nitrotyrosine in the damaged areas of the liver in APAP-treated mice, which is consistent with previous reports[36]. Notably, the nitrotyrosine level in the liver of MV-pretreated mice was dramatically reduced, suggesting that MV may also protect hepatocytes from nitration caused by APAP.

As the awareness of APAP hepatotoxicity has increased, various alternative strategies and experimental models, including both animal models and cell lines, have been employed to screen for substances that can prevent or treat APAP-induced hepatotoxicity from multiple perspectives. Herein, we utilized the AML12 cell line to investigate the hepatoprotective activity of MV. Specifically, we analyzed ROS levels, phosphorylated JNK level and cell death in vitro. Our in vitro experimental results indicated that MV alleviated the accumulation of ROS in AML12 cells caused by APAP, further mitigated JNK activation, and reduced cell death, which were consistent with our in vivo experimental findings.

In summary, our results indicate that MV mitigates APAP-induced ALI by reducing ROS levels and inhibiting JNK activation. Our findings suggest that MV could serve as a potential prophylactic agent to prevent APAP-induced ALI.

| 1. | Chidiac AS, Buckley NA, Noghrehchi F, Cairns R. Paracetamol (acetaminophen) overdose and hepatotoxicity: mechanism, treatment, prevention measures, and estimates of burden of disease. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2023;19:297-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cai X, Cai H, Wang J, Yang Q, Guan J, Deng J, Chen Z. Molecular pathogenesis of acetaminophen-induced liver injury and its treatment options. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2022;23:265-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Saito C, Zwingmann C, Jaeschke H. Novel mechanisms of protection against acetaminophen hepatotoxicity in mice by glutathione and N-acetylcysteine. Hepatology. 2010;51:246-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 285] [Cited by in RCA: 351] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jaeschke H. Mechanisms of sterile inflammation in acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2018;15:74-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chiew AL, Gluud C, Brok J, Buckley NA. Interventions for paracetamol (acetaminophen) overdose. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2:CD003328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Schmidt LE, Dalhoff K, Poulsen HE. Acute versus chronic alcohol consumption in acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. Hepatology. 2002;35:876-882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hodgman MJ, Garrard AR. A review of acetaminophen poisoning. Crit Care Clin. 2012;28:499-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tiwari M, Kakkar P. Plant derived antioxidants - Geraniol and camphene protect rat alveolar macrophages against t-BHP induced oxidative stress. Toxicol In Vitro. 2009;23:295-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Guo Q, Shi M, Sarengaowa, Xiao Z, Xiao Y, Feng K. Recent Advances in the Distribution, Chemical Composition, Health Benefits, and Application of the Fruit of Siraitia grosvenorii. Foods. 2024;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Takasaki M, Konoshima T, Murata Y, Sugiura M, Nishino H, Tokuda H, Matsumoto K, Kasai R, Yamasaki K. Anticarcinogenic activity of natural sweeteners, cucurbitane glycosides, from Momordica grosvenori. Cancer Lett. 2003;198:37-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nie J, Sui L, Zhang H, Zhang H, Yan K, Yang X, Lu S, Lu K, Liang X. Mogroside V protects porcine oocytes from in vitro ageing by reducing oxidative stress through SIRT1 upregulation. Aging (Albany NY). 2019;11:8362-8373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Song JL, Qian B, Pan C, Lv F, Wang H, Gao Y, Zhou Y. Protective activity of mogroside V against ovalbumin-induced experimental allergic asthma in Kunming mice. J Food Biochem. 2019;43:e12973. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Li Y, Zou L, Li T, Lai D, Wu Y, Qin S. Mogroside V inhibits LPS-induced COX-2 expression/ROS production and overexpression of HO-1 by blocking phosphorylation of AKT1 in RAW264.7 cells. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 2019;51:365-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Suzuki YA, Murata Y, Inui H, Sugiura M, Nakano Y. Triterpene glycosides of Siraitia grosvenori inhibit rat intestinal maltase and suppress the rise in blood glucose level after a single oral administration of maltose in rats. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:2941-2946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liu X, Zhang J, Li Y, Sun L, Xiao Y, Gao W, Zhang Z. Mogroside derivatives exert hypoglycemics effects by decreasing blood glucose level in HepG2 cells and alleviates insulin resistance in T2DM rats. J Funct Foods. 2019;63:103566. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chen M, Li L, Qin Y, Teng H, Lu C, Mai R, Zhu Z, Mo J, Qi Z. Mogroside V ameliorates astrocyte inflammation induced by cerebral ischemia through suppressing TLR4/TRADD pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 2025;148:114085. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Liu C, Dai LH, Dou DQ, Ma LQ, Sun YX. A natural food sweetener with anti-pancreatic cancer properties. Oncogenesis. 2016;5:e217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Li Q, Xu Q, Shi J, Dong W, Jin J, Zhang C. FAK inhibition delays liver repair after acetaminophen-induced acute liver injury by suppressing hepatocyte proliferation and macrophage recruitment. Hepatol Commun. 2024;8:e0531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Luo H, Peng C, Xu X, Peng Y, Shi F, Li Q, Dong J, Chen M. The Protective Effects of Mogroside V Against Neuronal Damages by Attenuating Mitochondrial Dysfunction via Upregulating Sirtuin3. Mol Neurobiol. 2022;59:2068-2084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Heymann F, Tacke F. Immunology in the liver--from homeostasis to disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:88-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 575] [Cited by in RCA: 870] [Article Influence: 87.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wang S, Song R, Wang Z, Jing Z, Wang S, Ma J. S100A8/A9 in Inflammation. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 466] [Cited by in RCA: 1064] [Article Influence: 133.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hanawa N, Shinohara M, Saberi B, Gaarde WA, Han D, Kaplowitz N. Role of JNK translocation to mitochondria leading to inhibition of mitochondria bioenergetics in acetaminophen-induced liver injury. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:13565-13577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 374] [Cited by in RCA: 448] [Article Influence: 24.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ramachandran A, Jaeschke H. A mitochondrial journey through acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Food Chem Toxicol. 2020;140:111282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Seki E, Brenner DA, Karin M. A liver full of JNK: signaling in regulation of cell function and disease pathogenesis, and clinical approaches. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:307-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 338] [Cited by in RCA: 418] [Article Influence: 29.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gunawan BK, Liu ZX, Han D, Hanawa N, Gaarde WA, Kaplowitz N. c-Jun N-terminal kinase plays a major role in murine acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:165-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 342] [Cited by in RCA: 374] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wang M, Sun J, Yu T, Wang M, Jin L, Liang S, Luo W, Wang Y, Li G, Liang G. Diacerein protects liver against APAP-induced injury via targeting JNK and inhibiting JNK-mediated oxidative stress and apoptosis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;149:112917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Du K, Ramachandran A, Jaeschke H. Oxidative stress during acetaminophen hepatotoxicity: Sources, pathophysiological role and therapeutic potential. Redox Biol. 2016;10:148-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in RCA: 419] [Article Influence: 41.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Nie J, Yan K, Sui L, Zhang H, Zhang H, Yang X, Lu S, Lu K, Liang X. Mogroside V improves porcine oocyte in vitro maturation and subsequent embryonic development. Theriogenology. 2020;141:35-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lin G, Luo D, Liu J, Wu X, Chen J, Huang Q, Su L, Zeng L, Wang H, Su Z. Hepatoprotective Effect of Polysaccharides Isolated from Dendrobium officinale against Acetaminophen-Induced Liver Injury in Mice via Regulation of the Nrf2-Keap1 Signaling Pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2018;2018:6962439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Parikh H, Pandita N, Khanna A. Phytoextract of Indian mustard seeds acts by suppressing the generation of ROS against acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in HepG2 cells. Pharm Biol. 2015;53:975-984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Radi R. Nitric oxide, oxidants, and protein tyrosine nitration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4003-4008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1106] [Cited by in RCA: 1139] [Article Influence: 51.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | James LP, McCullough SS, Lamps LW, Hinson JA. Effect of N-acetylcysteine on acetaminophen toxicity in mice: relationship to reactive nitrogen and cytokine formation. Toxicol Sci. 2003;75:458-467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | García-Monzón C, Majano PL, Zubia I, Sanz P, Apolinario A, Moreno-Otero R. Intrahepatic accumulation of nitrotyrosine in chronic viral hepatitis is associated with histological severity of liver disease. J Hepatol. 2000;32:331-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Laffey JG, Honan D, Hopkins N, Hyvelin JM, Boylan JF, McLoughlin P. Hypercapnic acidosis attenuates endotoxin-induced acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:46-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Nakamura T, Lipton SA. Nitric Oxide-Dependent Protein Post-Translational Modifications Impair Mitochondrial Function and Metabolism to Contribute to Neurodegenerative Diseases. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2020;32:817-833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Du K, Farhood A, Jaeschke H. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidant Mito-Tempo protects against acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Arch Toxicol. 2017;91:761-773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/