Published online Dec 27, 2025. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v17.i12.113359

Revised: September 15, 2025

Accepted: November 10, 2025

Published online: December 27, 2025

Processing time: 125 Days and 22.7 Hours

Numerous studies have reported specific expression profiles of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) that are associated with infectious, autoimmune, and inflammatory disorders, including chronic liver diseases.

To identify potential differences in the transcriptome profiles of PBMCs between male patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and healthy male adolescents.

PBMCs were isolated from 16 male adolescents with NAFLD and 14 healthy age-matched male peers. The collected cells were cultured in vitro for 18 hours without and with autologous fecal extracts (FEs). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were investigated using RNA sequencing. Levels of interleukin (IL)-6, tumor necrosis factor-α, IL-10, and IL-1β secreted into the culture medium were determined using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. DEGs were functionally analyzed through annotation according to the Gene Ontology and Reactome databases.

In total, 151 (118 protein-coding) and 97 (65 protein-coding) DEGs were identified when the RNA profiles of PBMCs stimulated without and with FEs, respectively, were compared between NAFLD patients and controls. Functional enrichment analysis of DEGs identified several pathways, which were predominantly involved in metabolism and inflammatory responses in non-stimulated and FE-stimulated PBMCs, respectively. FEs increased secretion of IL-6 and IL-1β by PBMCs isolated from controls and of all four cytokines by PBMCs isolated from NAFLD patients. IL-1β secretion was significantly higher in FE-stimulated PBMCs isolated from NAFLD patients than in those isolated from controls.

Our data suggest that changes in PBMC gene expression may provide candidate biomarkers for NAFLD deve

Core Tip: We studied immune cells from teenage boys with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and found that their gene activity and immune responses differ from those of healthy peers. These immune-related changes may serve as early indicators of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and provide insight into its pathogenesis. Our findings highlight the importance of immune profiling in adolescents and may contribute to future strategies for early diagnosis and intervention.

- Citation: Zeber-Lubecka N, Michalkiewicz J, Dabrowska M, Goryca K, Wierzbicka-Rucińska A, Jańczyk W, Jankowska I, Świąder-Leśniak A, Kubiszewska I, Ziemska-Legięcka J, Socha P, Ostrowski J. Transcriptome profiles of peripheral blood mononuclear cells differentiate male adolescents with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease from healthy peers. World J Hepatol 2025; 17(12): 113359

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v17/i12/113359.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v17.i12.113359

Blood, which comes into contact with cells, tissues, and organs of the entire organism, is a primary aspect of the immune defense system. Consequently, changes in the gene expression profiles of white blood cells are associated with a wide range of pathological conditions, including chronic inflammation and dysregulated immune responses. Our previous transcriptomic analyses of white blood cells from patients with two cholestatic liver diseases, namely, primary biliary cholangitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis, and two inflammatory bowel diseases, namely, Crohn’s disease and ul

Excessive fat accumulation, particularly visceral adiposity, drives hepatic steatosis and metabolic dysfunction; there

The pathophysiology of NAFLD in children shares key mechanisms with NAFLD in adults but also has distinct characteristics influenced by developmental and metabolic factors. Insulin resistance remains a central driver, leading to increased lipolysis, elevated free fatty acid influx, and hepatic triglyceride accumulation[5]. Notably, pediatric NAFLD often presents with a different histological pattern, with more portal-based inflammation and fibrosis in contrast to the lobular distribution in adults[6]. Genetic predisposition, particularly variants of the patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 gene, also plays a significant role in disease development and progression[7].

A “healthy” gut microbiota, which harvests nutrients and energy from the diet and produces metabolites with local and systemic actions, trains the host’s immune system and protects against opportunistic pathogens[8]. By contrast, imbalances in the gut microbiota, known as dysbiosis, affect appetite and the hedonic aspects of food intake, energy absorption, fat storage, and circadian rhythm through a complex network of host-microbe interactions[9]. Consequently, the gut microbiota is considered an important environmental factor linked to adiposity, diabetes, and dyslipidemia[10,11], and may be involved in the progression to NAFLD through metabolic endotoxemia, which causes insulin resistance, hepatic fat accumulation, and vascular dysfunction[12,13]. Studies of children aged 10-15 years reported altered α-diversity in those with obesity, NAFLD, and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, while β-diversity distinguished cases from controls[14]. Another study of obese adolescents aged 14-18 years with NAFLD identified specific microbial shifts, including increased abundances of Bifidobacterium and Prevotella, along with a decreased abundance of Lactobacillus[15].

The aim of our study was to identify potential differences in the transcriptome profiles of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) between male patients with NAFLD and healthy male adolescents. Additionally, considering the immunomodulatory potential of gut metabolites, we examined changes in gene expression of PBMCs in response to stimulation with fecal extracts (FEs) in vitro and whether these differences were related to secretion of selected cytokines.

The study included obese male adolescents with NAFLD and healthy male adolescents with normal body weight aged 14-17 years who were recruited at the Children’s Memorial Health Institute in Warsaw, Poland. The inclusion criteria were: (1) Overweight/obesity according to International Obesity Task Force criteria; and (2) Liver steatosis assessed using the FibroScan technique (controlled attenuation parameter values > 250 dB/m), measurement of alanine aminotransferase activity, and/or histological examination of liver biopsy samples. The exclusion criteria were: (1) Presence of chronic diseases affecting metabolism, including type 1 and type 2 diabetes, autoimmune diseases, chronic inflammatory diseases, or genetic syndromes associated with obesity; (2) Use of antibiotics, probiotics, prebiotics, or synbiotics within 3 months prior to fecal sample collection; (3) Use of medications that affect lipid metabolism or liver function; and (4) Incomplete clinical data or lack of consent to participate in the study. Overweight and obesity were defined according to the age- and sex-specific BMI cutoffs proposed by the International Obesity Task Force, which correspond to adult BMI values of 25 kg/m2 (overweight) and 30 kg/m2 (obesity) at age 18. These thresholds were derived using the LMS method, which models the distribution of BMI across age and sex by accounting for skewness (L), median (M), and variability (S). For male adolescents aged 14-17 years, the BMI cutoffs for obesity were as follows: Age 14: ≥ 26.84 kg/m2; age 15: ≥ 27.62 kg/m2; age 16: ≥ 28.30 kg/m2; age 17: ≥ 28.88 kg/m2. These values ensure consistency with international standards and enhance the reproducibility of the study[16]. It is important to note that the terminology for fatty liver disease has recently been updated. The term metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease has been proposed to replace NAFLD, emphasizing the role of metabolic dysfunction as a central criterion for diagnosis[17]. This change, endorsed by major hepatology societies, aims to improve disease classification, reduce stigma, and enhance clinical and research app

Targeted quantification of selected metabolites, including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs): Formic, acetic, propanoic, isobutyric, butyric, pentanoic, isocaproic and hexanoic acids as well as nine amino acids (AAs): Alanine, glycine, valine, leucine, isoleucine, proline, methionine, phenylalanine and tyrosine in stool samples was performed using gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (GC/MS). Stool samples were mechanically homogenized and derivatized with isobutyl chloroformate at a ratio of 50 μL per 650 μL of the sample or standard mixture. Metabolites were analyzed using gas chromatography coupled with a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer, Agilent 7000D (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, United states). A 5 milliseconds column (30 m, 0.25 mm, 0.50 μm) was used for metabolite separation, with injector, ion source, quadrupole, and transfer line temperatures set at 260 °C, 250 °C, 150 °C, and 275 °C, respectively. Data analysis was conducted using MassHunter software (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, United states). Differences in the relative abundance of AA and SCFAs were evaluated using the Mann-Whitney U test to determine statistical significance.

PBMCs were obtained from buffy-coat preparations after density gradient centrifugation of diluted whole blood overlaid on Ficoll medium, two washes with normal saline solution (0.85% sodium chloride), and suspension in 250 μL of this solution. Next, the cells were cultured at a density of 1 × 106 cells/mL in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum for 18 hours at 37 °C without and with FEs at a final dilution of 1:100. Metabolite extracts were prepared from autologous stools by mechanical homogenization of 200 mg of a stool sample suspended in 1 mL of methanol in Ohaus homogenizer lysing tubes at 4 °C, followed by homogenization using a Bioruptor Plus (Diagenode, Denville, NJ, United states) with a 15-second on/off cycle for 2 minutes at high intensity. After centrifugation for 15 minutes at 18000 g, the supernatants were stored at -80 °C until use.

Following incubation, cells were collected by centrifugation and stored at -80 °C until further analysis. The levels of interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and IL-10 in the supernatants were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. Results were expressed in pg/mL after subtracting background levels from non-stimu

Total RNA was isolated from frozen PBMCs using a mirVana™ PARIS™ RNA and Native Protein Purification Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United states), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration of isolated RNA and its purity were assessed by using a NanoDrop™ 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United states) to determine the A260/280 and A260/230 ratios, respectively. The RNA integrity number was assessed using an Agilent RNA 6000 Nano Kit on a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, United states). Whole-transcriptome libraries were sequenced on the NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United states). Depths of 30 million (6 Gb) paired-end 100-bp reads were generated for each sample. Mapped reads were associated with transcripts from the GRCh38 database (Ensembl, version 109) using HTSeq-count (version 2.0.1) with default parameters except the stranded set was changed to “reverse”. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were selected using the DESeq2 package (version 1.42.1). P-values were adjusted (padj) for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg algorithm. Padj-values less than 0.05 were considered significant. Overrepresentation according to the Gene Ontology (GO) and Reactome databases was assessed with the Cytoscape platform (version 3.6.1) in combination with the ClueGO plugin (version 2.5.1). Default settings were applied with padj-values adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg correction, and a significance threshold was set at padj < 0.05.

In this study, we enrolled 16 male adolescents with NAFLD and 14 age-matched male peers as controls to assess the transcriptome profiles of PBMCs and their responses to stimulation with FEs in vitro. The clinical and biochemical parameters are presented in Table 1. Adolescents with NAFLD had significantly higher BMIs (P < 0.0001) and BMI z-scores (P < 0.0001), higher serum alanine aminotransferase (P < 0.0001) and aspartate aminotransferase (P = 0.0004) activities, lower serum high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol concentrations (P < 0.0001), higher triglyceride concentrations (P = 0.0005), and higher ammonia concentrations (P < 0.0001). Fasting glucose, insulin, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance, blood pressure, and urea levels did not significantly differ between the groups.

| Total (n = 30) | Control (n = 14) | NAFLD (n = 16) | P value |

| Age, years | 15.09 (13.27-17.85) | 15.97 (14.42-17.88) | 0.1661 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 20.91 (18.85-23.21) | 31.14 (28.52-33.59) | < 0.0001a |

| BMI z-score | 0.5950 (0.1350-1.080) | 2.555 (2.295-2.955) | < 0.0001a |

| ALT (U/L) | 13.00 (12.00-17.00) | 43.00 (27.25-94.00) | < 0.0001a |

| AST (U/L) | 15.00 (12.00-20.00) | 32.00 (22.00-41.00) | 0.0004a |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.6600 (0.5000-2.340) | 0.6100 (0.4200-0.9100) | 0.2866 |

| GGTP (U/L) | 21.50 (15.50-23.50) | 30.50 (19.00-50.25) | 0.1181 |

| TC (mg/dL) | 157.0 (133.0-171.0) | 149.0 (139.8-179.0) | 0.8366 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 96.00 (63.60-107.5) | 88.50 (71.25-97.00) | 0.5315 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 53.00 (49.00-54.00) | 35.00 (31.50-40.00) | < 0.0001a |

| TG (mg/dL) | 67.50 (58.50-86.50) | 161.5 (100.5-239.0) | 0.0005a |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 86.70 (84.05-88.15) | 88.90 (82.90-94.10) | 0.1846 |

| Insulin (mU/mL) | 12.80 (9.013-13.98) | 13.87 (9.600-23.33) | 0.2750 |

| HOMA-IR | 2.77 (1.870-2,975) | 3.010 (2.190-5.470) | 0.1995 |

| Systolic pressure (mmHg) | 121.0 (111.3-125.0) | 120.0 (112.5-127.5) | 0.9904 |

| Diastolic pressure | 67.00 (58.50-75.50) | 70.00 (63.00-75.50) | 0.5645 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 26.90 (21.70-35.41) | 22.50 (18.10-27.50) | 0.3301 |

| Ammonaemia (μmol/L) | 61.20 (52.65-72.25) | 495.4 (349.6-631.8) | < 0.0001a |

Targeted GC/MS analysis was performed to quantify a predefined set of metabolites in stool samples. Specifically, eight SCFAs: Formic, acetic, propanoic, isobutyric, butyric, pentanoic, isocaproic, hexanoic acids and nine AAs: Alanine, glycine, valine, leucine, isoleucine, proline, methionine, phenylalanine, and tyrosine were measured. The relative abundance of these SCFAs and AAs did not differ significantly between children in the control and NAFLD groups (Supplementary Figure 1).

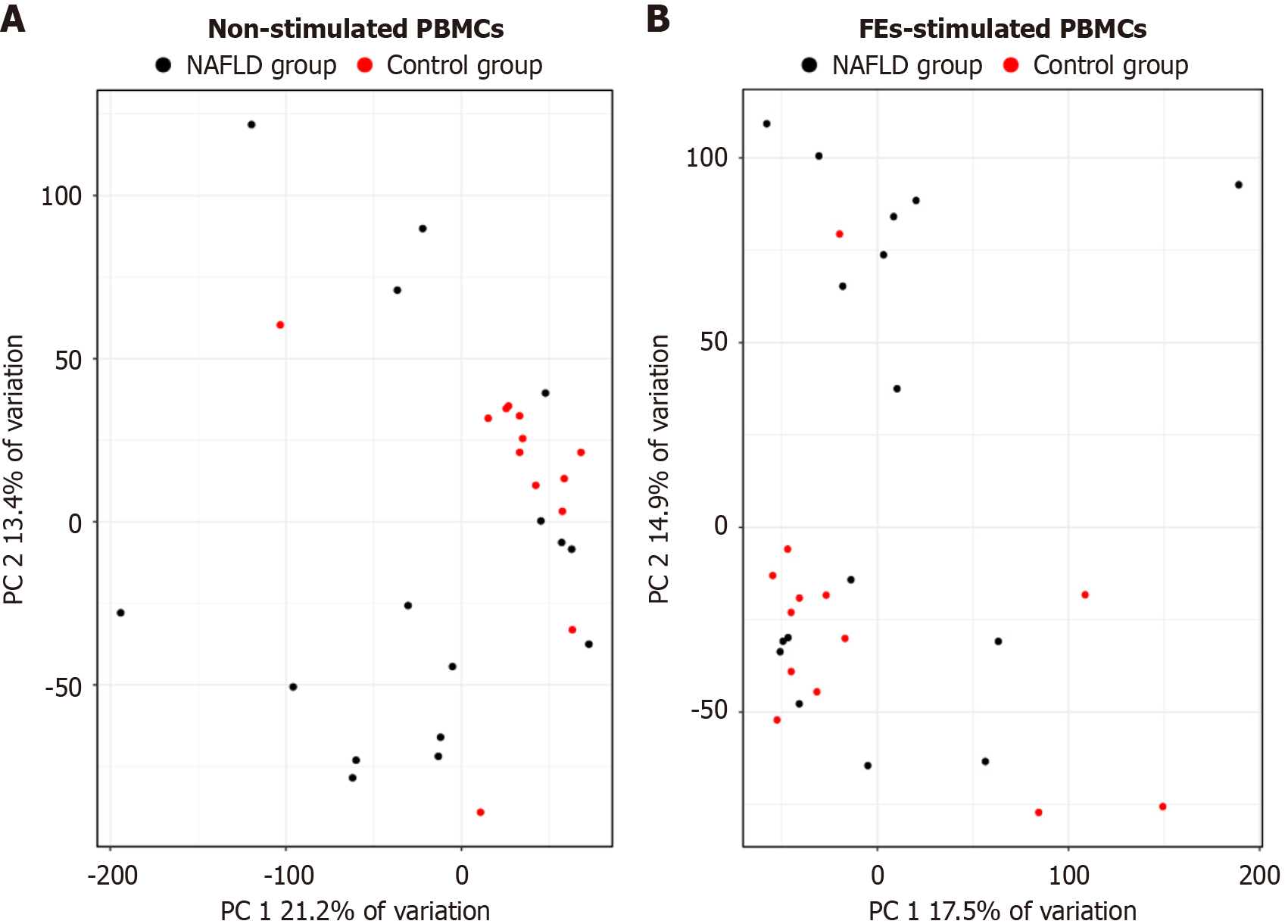

Whole-transcriptome sequencing was performed using RNA isolated from non-stimulated and FE-stimulated PBMCs. Principal component analysis based on gene expression profiles showed a tendency toward separation between non-stimulated (Figure 1A) and FE-stimulated (Figure 1B) PBMCs from NAFLD patients and controls, although the clustering was not complete and some overlap between groups was observed.

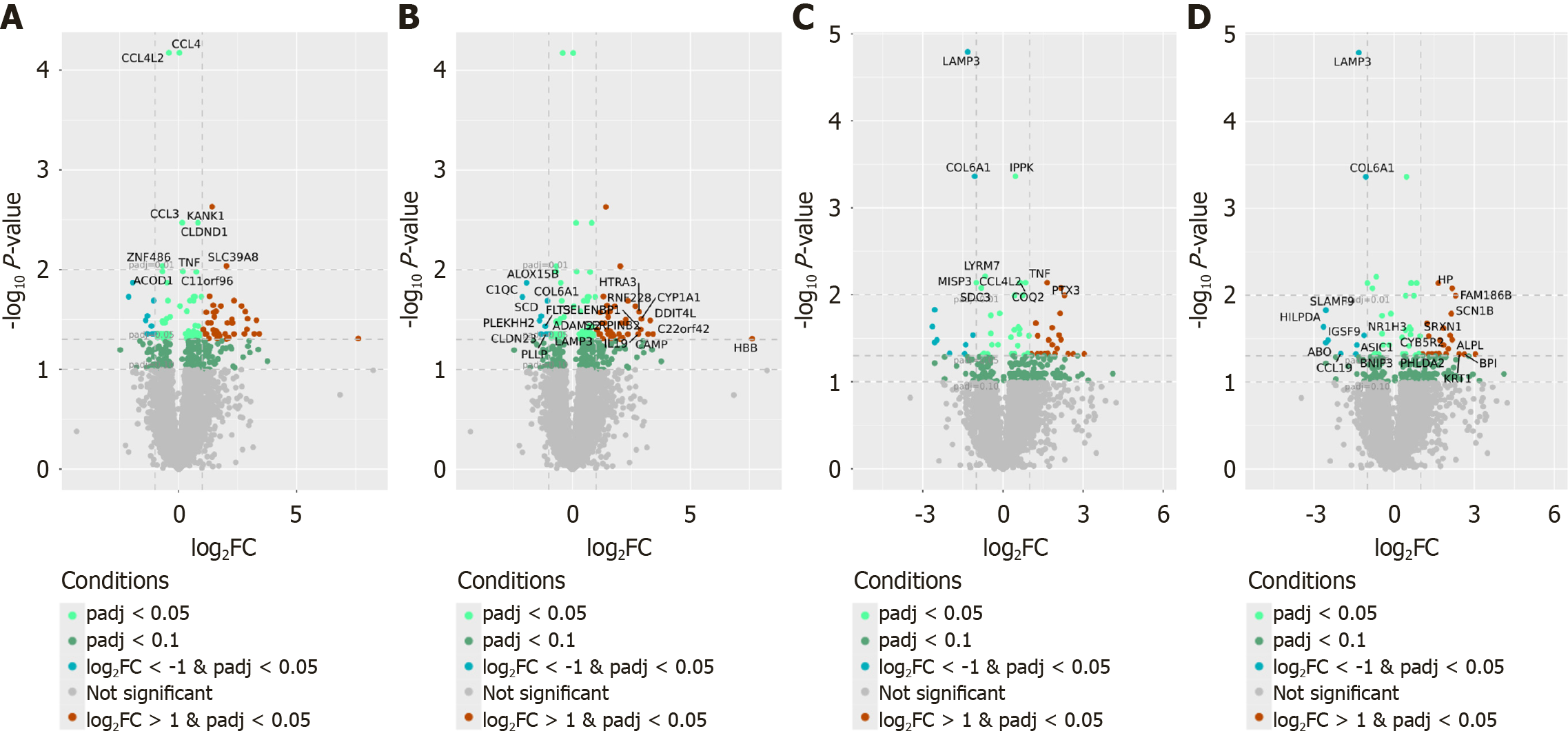

Among genes with at least 1024 reads in total, 151 (118 protein-coding) and 97 (65 protein-coding) DEGs were identified in the comparison of NAFLD patients and controls using non-stimulated and FE-stimulated PBMCs, respectively (padj < 0.05) (Supplementary Table 1). Of these, 76 (64%) and 43 (66%) protein-coding genes were more highly expressed in non-stimulated and FE-stimulated PBMCs isolated from NAFLD patients, respectively, than in those isolated from controls. The top DEGs whose expression most significantly differed between PBMCs isolated from NAFLD patients and those isolated from controls are presented in Figure 2.

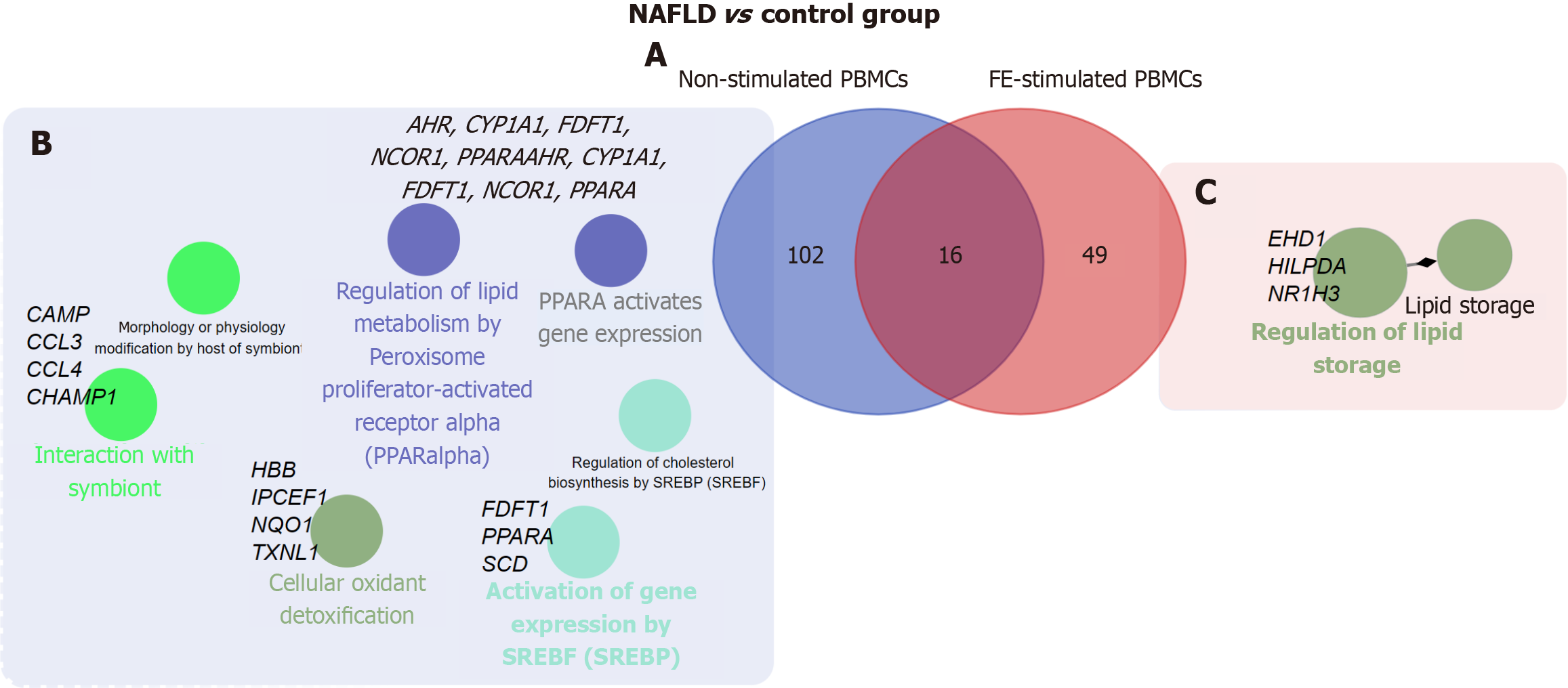

Among the protein-coding DEGs identified in the comparison of NAFLD patients and controls, 102 and 49 were unique to non-stimulated and FE-stimulated PBMCs, respectively. The 16 shared DEGs comprised a core set of genes that consistently differentiated NAFLD patients and controls regardless of whether PBMCs were stimulated with FEs (Figure 3, Supplementary Table 2). Functional enrichment analysis of protein-coding DEGs between NAFLD patients and controls in non-stimulated PBMCs identified seven pathways, including biological process (BP)-related (cellular oxidant detoxification and interaction with symbiont) and Reactome pathways, such as regulation of lipid metabolism by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha and activation of gene expression by sterol regulatory element binding transcription factors (Figure 3, Supplementary Table 2). A similar comparison using FE-stimulated PBMCs identified only two BP-related pathways associated with regulation of lipid storage (Figure 3, Supplementary Table 2).

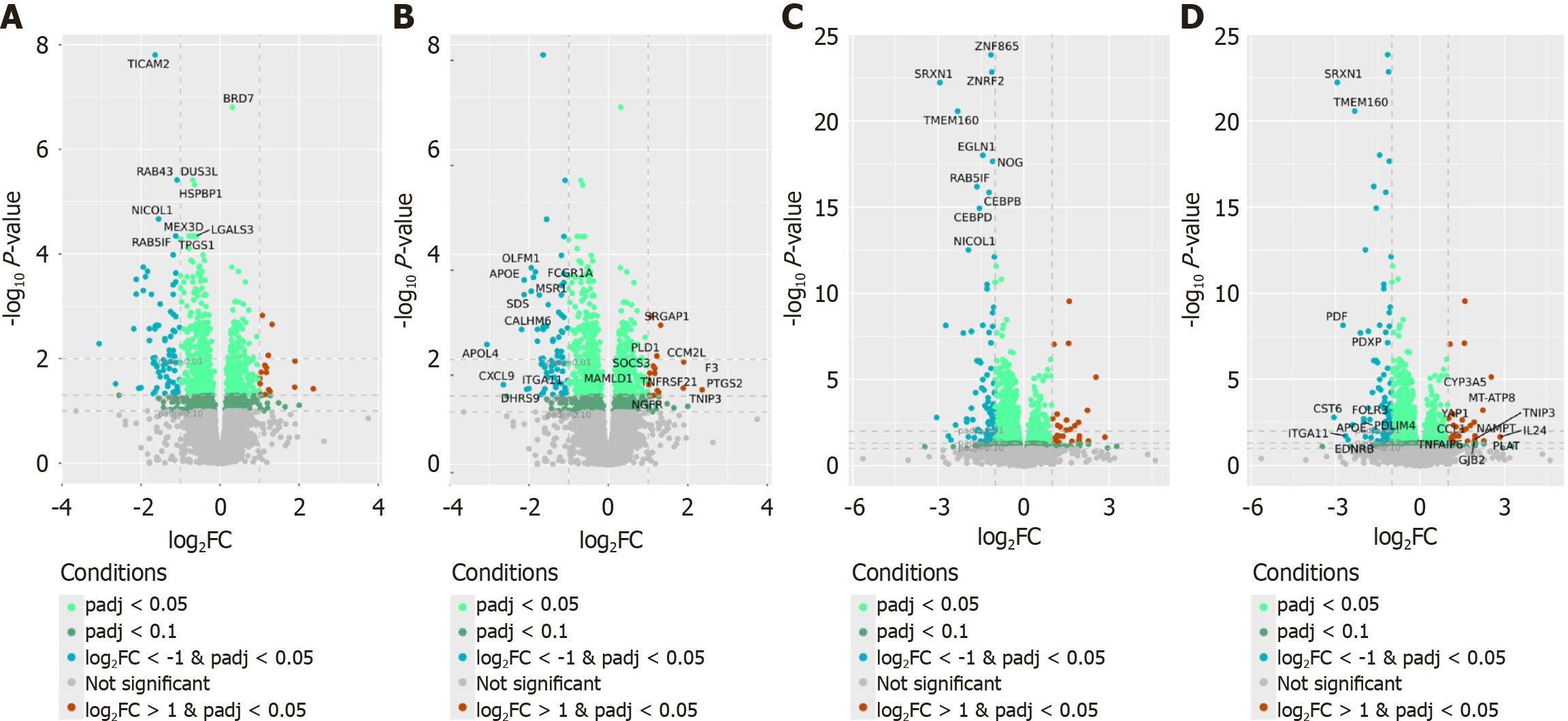

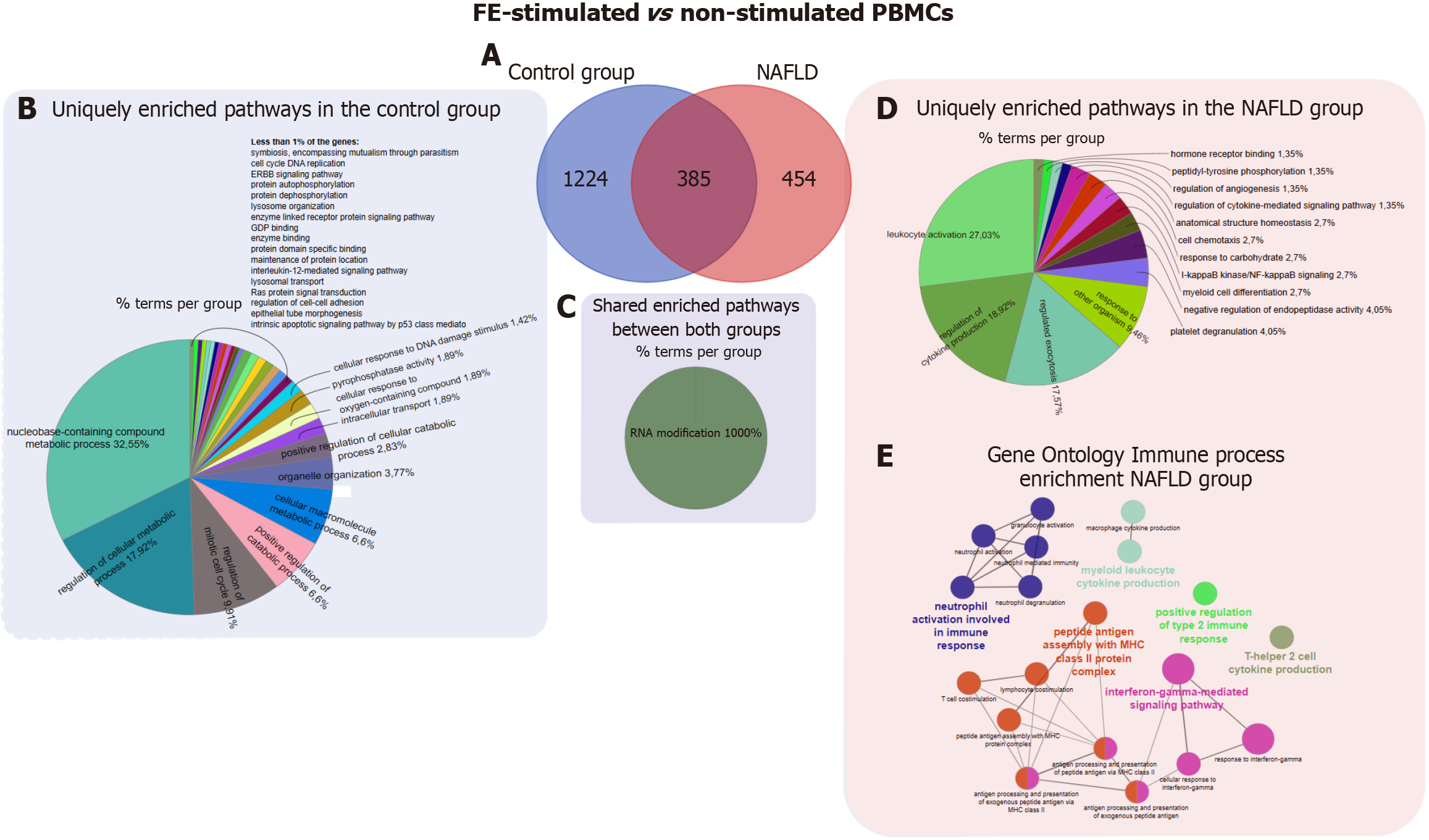

Next, we compared FE-stimulated and non-stimulated PBMCs isolated from NAFLD patients and controls. In total, 992 and 1943 DEGs were identified in NAFLD and control samples, respectively (padj < 0.05). Independently for NAFLD and control samples, pairwise comparisons were performed of FE-stimulated and non-stimulated PBMCs, which identified 839 and 1609 protein-coding DEGs, respectively (padj < 0.05) (Supplementary Table 3). Of these, 317 (37.78%) and 542 (33.67%) protein-coding genes were more highly expressed in FE-stimulated PBMCs than in non-stimulated PBMCs of NAFLD patients and controls, respectively. Figure 4 presents the top protein-coding DEGs whose expression most significantly differed between FE-stimulated and non-stimulated PBMCs isolated from NAFLD patients and controls.

As shown in the Venn diagram, among the protein-coding DEGs identified in the comparison of FE-stimulated and non-stimulated PBMCs, 454 were unique to NAFLD patients, 1224 were unique to controls, and 385 were shared (Figure 5). Functional enrichment analysis was performed of both unique and shared protein-coding DEGs. For DEGs unique to the control group in the comparison of FE-stimulated and non-stimulated PBMCs, we identified 213 pathways (padj < 0.05) (Supplementary Table 4). The most significant pathways according to BP and MF were nucleobase-containing compound metabolic process, regulation of metabolic process, and regulation of mitotic cell cycle (Figure 5). Only one BP (regulation of cell-cell adhesion) and one Reactome pathway (signaling by G protein-coupled receptor) (padj < 0.05) were shared in samples from NAFLD patients and controls. By contrast, for unique genes in the comparison of FE-stimulated and non-stimulated PBMCs isolated from NAFLD patients, functional enrichment analysis identified 75 pathways (padj < 0.05) (Supplementary Table 4) according to the BP and MF term categories of the GO database, including leukocyte activation, regulation of cytokine production, and regulated exocytosis (Figure 5). Four Reactome pathways were also identified, including cytokine signaling in immune system, neutrophil degranulation, and interferon-gamma signaling. Interestingly, the 385 genes whose expression changed in response to FE stimulation in PBMCs isolated from both NAFLD patients and controls appeared to be enriched for only one pathway related to the BP RNA modification (padj < 0.05) (Figure 5). We also identified unique DEGs enriched for Reactome pathways, including gap junction degradation and formation of annular gap junctions (padj < 0.05). Additionally, functional enrichment analysis at the GO - immune system process level identified nine significant pathways (padj < 0.05) only for unique genes in the comparison of FE-stimulated and non-stimulated PBMCs isolated from NAFLD patients. These pathways included response to interferon-gamma, neutrophil degranulation, and T-helper 2 cell cytokine production (Figure 5). By contrast, the DEGs unique to the control group and the shared DEGs were not enriched for any pathways related to immune processes.

To further identify genes whose altered expression in NAFLD was related to FE stimulation, a two-factor model (NAFLD × FE stimulation) was applied to the four transcriptional datasets. Expression of four miRNA-coding genes and one rRNA-coding gene in PBMCs isolated from NAFLD patients was significantly dependent on FE stimulation (padj < 0.05) (Table 2). Expression of miRNA and rRNA genes showed negative and positive interaction effects with FE stimulation, respectively.

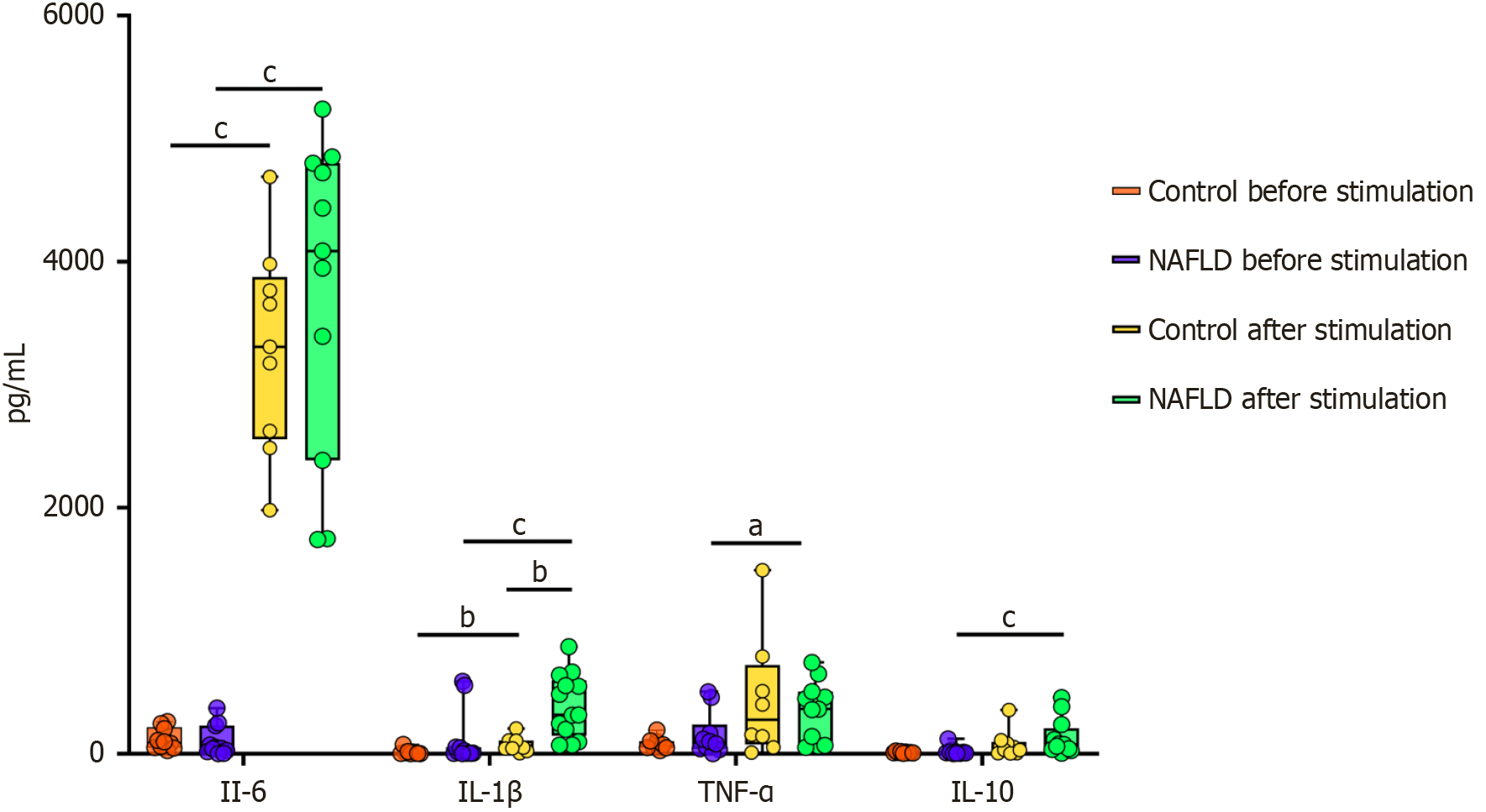

Figure 6 illustrates the levels of IL-6, TNF-α, IL-10, and IL-1β secreted by cultured PBMCs. Following FE stimulation, cytokine levels were significantly changed in all groups. IL-6 concentrations increased markedly after FE stimulation in both the control and NAFLD groups, with a significantly higher response in the latter group (P < 0.0001), indicative of an amplified pro-inflammatory reaction. IL-1β levels also rose substantially after FE stimulation, particularly in the NAFLD group, with significant differences in both the control and NAFLD groups (P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively). TNF-α levels significantly increased after FE stimulation in the NAFLD group (P < 0.05). Additionally, levels of IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine, significantly increased after FE stimulation in the NAFLD group (P < 0.001). These findings suggest that individuals with NAFLD exhibit enhanced inflammatory and regulatory cytokine responses, which reflect altered immune reactivity compared with healthy controls.

PBMCs are a crucial part of the human immune system and play a central role in coordinating immune responses[18]. Numerous studies have reported specific transcriptome profiles measured in whole blood samples that are associated with autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, infectious disorders, psychiatric, cardiovascular, neurological, and neoplastic diseases, as well as various environmental factors[1]. This study aimed to compare the transcriptome profiles of PBMCs between male adolescents with NAFLD and healthy, age-matched male peers. NAFLD patients displayed a higher body weight, higher serum aminotransferase activity, and more frequently concurrent dyslipidemia and hyperammonemia than controls. However, carbohydrate metabolism parameters did not significantly differ between NAFLD patients and controls.

Gene expression profiles of PBMCs cultured for 18 hours with or without FEs revealed distinct transcriptomic patterns between NAFLD patients and healthy controls. Although stimulation influenced the number and identity of DEGs, a core set of 16 protein-coding genes consistently differentiated NAFLD patients from controls across both conditions. This may suggest that certain immunometabolic alterations in NAFLD are stable and detectable regardless of external stimulation. Functional enrichment analysis of protein-coding DEGs in non-stimulated PBMCs revealed transcriptional changes associated with key BPs, including cellular stress responses, host-microbiota interactions, and metabolic regulation. These alterations suggest that even in the absence of stimulation, PBMCs from adolescents with NAFLD exhibit a transcriptional profile indicative of systemic immune activation and immunometabolic imbalance. The involvement of genes linked to detoxification, lipid signaling, and barrier-related communication may further support the notion of extra

Recent studies reported significant changes in PBMCs associated with pathological liver conditions. A large-scale flow cytometric analysis demonstrated differences in the percentage and number of peripheral blood lymphocytes between patients with primary liver cancer and those with benign liver disease[34]. Single-cell RNA sequencing identified 87 upregulated and 12 downregulated DEGs in monocytes and 101 upregulated and 15 downregulated DEGs in natural killer cells derived from PBMCs of individuals with autoimmune hepatitis, and the enriched GO terms were mainly related to antigen processing and presentation, interferon-gamma-mediated signaling, and neutrophil degranulation and activation[35]. Cellular and transcriptional profiling of peripheral blood collected during treatment of patients with chronic hepatitis C determined a pre-treatment and post-treatment gene expression signature associated with interferon signaling, T-cell dysfunction, and T-cell co-stimulation that had a high predictive capacity for distinguishing treatment outcomes[36]. Transcriptomic analysis of PBMCs identified 2381 DEGs and 776 differentially expressed transcripts between patients with hepatitis B-related acute-on-chronic liver failure, patients with chronic hepatitis B, and healthy controls, and GO analysis identified 114 GO terms clustered into 12 groups. Validation of the top six genes (cytochrome p450 family 19 subfamily a member 1, semaphorin 6b, inhibin beta a subunit, defensin, alpha, 1 pseudogene 1, azurocidin 1, and defensin, alpha 4) via quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction confirmed the RNA sequencing results, with areas under the receiver operating characteristic curves exceeding 0.8[37]. The integration of transcriptomics and proteomics into a multi-omics model analyzing alcohol-associated liver diseases improved the classification accuracy of PBMC data[38]. Transcriptomic analysis of PBMCs from patients with primary biliary cholangitis found that anti-inflammatory activity of monocytes, regulation of T-helper 1 cells, and activation of Tregs are interconnected and more prominent in responders to ursodeoxycholic acid treatment than in non-responders[39].

The liver and gut communicate via the biliary tract, portal vein, and systemic circulation. The liver releases bile acids and numerous bioactive mediators, while metabolites produced in the intestine translocate to the liver through the portal vein[1]. Consequently, crosstalk between the gut and liver may contribute to common mechanisms underlying liver and immune disorders. Next, we compared the transcriptome profiles of FE-stimulated PBMCs between the NAFLD and control groups. Some of the 65 differentially expressed transcripts that responded to FE stimulation in the NAFLD group are primarily linked to regulation of lipid storage, including hypoxia-inducible lipid droplet-associated protein, which plays a role in lipid droplet formation and hypoxia-driven lipid metabolism[40], and Bcl-2 19-kDa interacting protein 3, which is associated with mitophagy and lipid degradation[41]. The upregulated bactericidal permeability-increasing protein gene encodes a lipopolysaccharide-binding protein[42] that may enhance nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells activation and contribute to activation of toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signaling by microbial-derived pro-inflammatory mediators. Four cytokines, namely, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-10, and IL-1β, which are secreted by PBMCs, were analyzed in the culture medium. Secretion of all changed in response to FE stimulation in PBMCs isolated from NAFLD patients, while secretion of only two, namely, IL-6 and IL-1β, changed in response to FE stimulation in PBMCs isolated from controls. IL-1β production was significantly higher in FE-stimulated PBMCs isolated from NAFLD patients than in those isolated from controls. IL-1β is a key pro-inflammatory cytokine that drives immune cell recruitment and activation, and is thus linked to the C-C motif chemokine ligand family of chemokines, which mediate leukocyte trafficking and inflammatory responses[43].

Functional analysis of transcripts that distinguished non-stimulated and FE-stimulated PBMCs isolated from NAFLD patients revealed that DEGs were mainly involved in inflammatory responses, including leukocyte activation, cytokine regulation, and neutrophil degranulation. The enrichment of pathways related to interferon-gamma responses, T-helper 2 cell cytokine production, and chronic inflammation further highlights FE-related immune dysregulation in PBMCs isolated from NAFLD patients. Among key genes contributing to this response, suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 encodes a suppressor of cytokine signaling in the Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription pathway[44]. tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 21, which encodes a member of the TNF receptor superfamily, plays a role in apoptosis and immune cell regulation[45]. prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (cyclooxygenase-2) encodes an enzyme involved in prostaglandin synthesis and mediation of inflammatory responses and is directly linked to chronic inflammation, a hallmark of NAFLD pathology[46]. TIR domain-containing adaptor molecule 2 (TICAM2), which encodes an adaptor protein in TLR signaling, plays a crucial role in activation of innate immune responses, especially through pattern recognition receptor pathways[47]. These pathways help immune cells detect pathogen-associated and damage-associated molecular patterns, initiating inflammatory responses. TICAM2 participates in TLR4 signaling, a key pattern recognition receptor pathway that recognizes bacterial liposaccharide and other microbial components. Upon activation, TLR4 recruits adaptor proteins like TICAM2, leading to downstream signaling cascades such as the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells and Interferon regulatory factor 3 pathways, which produce pro-inflammatory cytokines, interferons, and chemokines that amplify immune responses[47]. LGALS3, which encodes galectin-3, significantly influences NAFLD progression by modulating inflammation, fibrosis, and immune cell activation[48]. In our study, the upregulation of LGALS3 in non-stimulated PBMCs isolated from NAFLD patients may suggests there is a baseline pro-inflammatory state, independent of external stimulation. Galectin-3, a β-galactoside-binding lectin, regulates macrophage activation, cytokine production, and tissue remodeling, which are all key processes in NAFLD pathology[48]. Additionally, it is involved in macrophage polarization and promotes the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype that sustains chronic inflammation[19].

DEGs that distinguished non-stimulated and FE-stimulated PBMCs isolated from controls were associated with nucleobase metabolism, cell cycle regulation, and broader metabolic processes, reflecting a baseline cellular maintenance function. Expression of IL24, which is involved in cytokine signaling and apoptosis[49], increased following FE stimulation, which suggests that immune activation of PBMCs isolated from controls was due to direct FE exposure rather than their inherent characteristics. Cytochrome P450 3A5 plays a central role in xenobiotic detoxification and steroid metabolism[50], aligning with the observed enrichment of metabolic pathways. Plasminogen activator, tissue-type, which encodes tissue plasminogen activator, is primarily involved in fibrinolysis and extracellular matrix remodeling[51], reinforcing the structural rather than immune-related nature of the response of PBMCs isolated from controls. PDZ and LIM domain protein 4, which encodes a cytoskeletal regulator, contributes to cellular organization and stability[52]. The expression of gap junction beta 2, which encodes a key component of gap junctions[53], suggests an emphasis on intercellular coordination and homeostasis, which contrasts with the immune-driven responses observed in PBMCs isolated from NAFLD patients.

Interestingly, despite the smaller number of DEGs observed in FE-stimulated PBMCs from NAFLD patients compared to controls, the NAFLD cells exhibited a more robust cytokine response. This apparent paradox may reflect a state of immune priming, where circulating immune cells are pre-activated due to chronic low-grade inflammation and metabolic stress[54,55]. Such priming could result in a more efficient functional response with fewer transcriptional changes. Similar phenomena have been described in other chronic inflammatory conditions, like obesity, type 2 diabetes, and autoimmune diseases, where immune cells exhibit heightened responsiveness despite limited transcriptional reprogramming[56,57]. In these contexts, monocytes and macrophages often show amplified cytokine secretion and effector functions, driven by epigenetic priming, altered signaling thresholds, or post-transcriptional regulation[58]. These mechanisms may also contribute to the disproportionate cytokine output observed in NAFLD PBMCs following FE stimulation.

FE stimulation induced substantial transcriptomic changes in PBMCs from both NAFLD patients and healthy controls, though the nature of these changes differed between groups. In NAFLD, the affected genes were predominantly associated with immune activation, cytokine signaling, and stress-related cellular responses, suggesting heightened sensitivity of circulating immune cells to microbial stimuli. These processes included leukocyte priming, interferon-related signaling, and regulated exocytosis, pointing to a pro-inflammatory and reactive immune phenotype. In contrast, the transcriptomic response in healthy controls was more closely linked to general metabolic regulation and cell cycle control, indicating a more homeostatic and proliferative cellular profile. These differences may reflect underlying immunometabolic reprogramming in NAFLD and support the relevance of PBMCs as a window into systemic disease processes.

It is important to acknowledge that the relatively small sample size represents a limitation of this study. Although recruiting pediatric participants for transcriptomic research poses logistical and ethical challenges, the limited number of biological replicates may reduce statistical power and increase the risk of false-positive findings or omission of genes with subtle expression changes. Therefore, the current results should be interpreted with caution, particularly in the context of differential gene expression and functional enrichment analyses. To reflect this, we have reframed our study as exploratory in nature. The identified DEGs and enriched pathways should be considered candidate findings, which require validation in larger, independent cohorts. While broad BPs such as immune activation and metabolic stress appear robust, more specific pathway-level interpretations may be influenced by sample variability and should be treated as preliminary. Despite these limitations, our approach provides valuable insights into systemic immune alterations in adolescent NAFLD and highlights the potential of PBMC-based transcriptomic profiling as a tool for identifying early biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

NAFLD is increasingly recognized as a metabolic disorder driven by complex immune dysregulation[59]. While hepatic lipid accumulation initiates inflammation, altered interplay between innate and adaptive immunity contributes to disease progression and systemic metabolic disturbances[60,61]. Crosstalk between the gut and liver, including microbial and metabolite-derived signals, may further amplify immune activation[62]. Our exploratory study demonstrates that transcriptomic profiling of PBMCs, particularly following stimulation with autologous FEs, may reveal candidate biomarkers and provide preliminary mechanistic insights into immune alterations in adolescent NAFLD. Although targeted GC/MS analysis of selected fecal metabolites (SCFAs and AAs) did not show significant differences between groups, the presence of these compounds supports the biological relevance of the extracts. Taken together, our findings provide a preliminary foundation for future research into PBMC-based candidate biomarkers and host-microbiota interactions in NAFLD. Validation in larger cohorts and integration with untargeted metabolomics and microbiome data will be essential to further explore and clarify the molecular mechanisms underlying disease development and progression.

| 1. | Ostrowski J, Goryca K, Lazowska I, Rogowska A, Paziewska A, Dabrowska M, Ambrozkiewicz F, Karczmarski J, Balabas A, Kluska A, Piatkowska M, Zeber-Lubecka N, Kulecka M, Habior A, Mikula M; Polish PBC study Group; Polish IBD study Group. Common functional alterations identified in blood transcriptome of autoimmune cholestatic liver and inflammatory bowel diseases. Sci Rep. 2019;9:7190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bonsembiante L, Targher G, Maffeis C. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in obese children and adolescents: a role for nutrition? Eur J Clin Nutr. 2022;76:28-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Anderson EL, Howe LD, Jones HE, Higgins JP, Lawlor DA, Fraser A. The Prevalence of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0140908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 459] [Cited by in RCA: 690] [Article Influence: 62.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Arshad T, Paik JM, Biswas R, Alqahtani SA, Henry L, Younossi ZM. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Prevalence Trends Among Adolescents and Young Adults in the United States, 2007-2016. Hepatol Commun. 2021;5:1676-1688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kasper P, Martin A, Lang S, Kütting F, Goeser T, Demir M, Steffen HM. NAFLD and cardiovascular diseases: a clinical review. Clin Res Cardiol. 2021;110:921-937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 435] [Article Influence: 72.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Kleiner DE, Makhlouf HR. Histology of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis in Adults and Children. Clin Liver Dis. 2016;20:293-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yuan L, Terrrault NA. PNPLA3 and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: towards personalized medicine for fatty liver. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2020;9:353-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kulecka M, Czarnowski P, Bałabas A, Turkot M, Kruczkowska-Tarantowicz K, Żeber-Lubecka N, Dąbrowska M, Paszkiewicz-Kozik E, Walewski J, Ługowska I, Koseła-Paterczyk H, Rutkowski P, Kluska A, Piątkowska M, Jagiełło-Gruszfeld A, Tenderenda M, Gawiński C, Wyrwicz L, Borucka M, Krzakowski M, Zając L, Kamiński M, Mikula M, Ostrowski J. Microbial and Metabolic Gut Profiling across Seven Malignancies Identifies Fecal Faecalibacillus intestinalis and Formic Acid as Commonly Altered in Cancer Patients. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:8026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | de Wouters d'Oplinter A, Rastelli M, Van Hul M, Delzenne NM, Cani PD, Everard A. Gut microbes participate in food preference alterations during obesity. Gut Microbes. 2021;13:1959242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Woting A, Blaut M. The Intestinal Microbiota in Metabolic Disease. Nutrients. 2016;8:202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang B, Kong Q, Li X, Zhao J, Zhang H, Chen W, Wang G. A High-Fat Diet Increases Gut Microbiota Biodiversity and Energy Expenditure Due to Nutrient Difference. Nutrients. 2020;12:3197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 40.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Di Vincenzo F, Del Gaudio A, Petito V, Lopetuso LR, Scaldaferri F. Gut microbiota, intestinal permeability, and systemic inflammation: a narrative review. Intern Emerg Med. 2024;19:275-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 633] [Article Influence: 316.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Corrao S, Calvo L, Granà W, Scibetta S, Mirarchi L, Amodeo S, Falcone F, Argano C. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: A pathophysiology and clinical framework to face the present and the future. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2025;35:103702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Del Chierico F, Nobili V, Vernocchi P, Russo A, De Stefanis C, Gnani D, Furlanello C, Zandonà A, Paci P, Capuani G, Dallapiccola B, Miccheli A, Alisi A, Putignani L. Gut microbiota profiling of pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and obese patients unveiled by an integrated meta-omics-based approach. Hepatology. 2017;65:451-464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 398] [Cited by in RCA: 554] [Article Influence: 61.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Amrousy DE, Ashry HE, Maher S, Elsayed Y, Hasan S. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and the gut microbiota in adolescents: is there a relationship? BMC Pediatr. 2024;24:779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ. 2000;320:1240-1243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10513] [Cited by in RCA: 10627] [Article Influence: 408.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zhang GY, Brandman D. A Clinical Update on MASLD. JAMA Intern Med. 2025;185:105-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sen P, Kemppainen E, Orešič M. Perspectives on Systems Modeling of Human Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells. Front Mol Biosci. 2017;4:96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Vonderlin J, Chavakis T, Sieweke M, Tacke F. The Multifaceted Roles of Macrophages in NAFLD Pathogenesis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;15:1311-1324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Simonson B, Subramanya V, Chan MC, Zhang A, Franchino H, Ottaviano F, Mishra MK, Knight AC, Hunt D, Ghiran I, Khurana TS, Kontaridis MI, Rosenzweig A, Das S. DDiT4L promotes autophagy and inhibits pathological cardiac hypertrophy in response to stress. Sci Signal. 2017;10:eaaf5967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Vogel CF, Chang WL, Kado S, McCulloh K, Vogel H, Wu D, Haarmann-Stemmann T, Yang G, Leung PS, Matsumura F, Gershwin ME. Transgenic Overexpression of Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Repressor (AhRR) and AhR-Mediated Induction of CYP1A1, Cytokines, and Acute Toxicity. Environ Health Perspect. 2016;124:1071-1083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Liu W, Baker SS, Baker RD, Nowak NJ, Zhu L. Upregulation of hemoglobin expression by oxidative stress in hepatocytes and its implication in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wu R, Kang R, Tang D. Mitochondrial ACOD1/IRG1 in infection and sterile inflammation. J Intensive Med. 2022;2:78-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Liu MJ, Bao S, Gálvez-Peralta M, Pyle CJ, Rudawsky AC, Pavlovicz RE, Killilea DW, Li C, Nebert DW, Wewers MD, Knoell DL. ZIP8 regulates host defense through zinc-mediated inhibition of NF-κB. Cell Rep. 2013;3:386-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 285] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Capaldo CT. Claudin Barriers on the Brink: How Conflicting Tissue and Cellular Priorities Drive IBD Pathogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:8562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Nguyen MT, Lee W. Kank1 Is Essential for Myogenic Differentiation by Regulating Actin Remodeling and Cell Proliferation in C2C12 Progenitor Cells. Cells. 2022;11:2030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Tian R, Zuo X, Jaoude J, Mao F, Colby J, Shureiqi I. ALOX15 as a suppressor of inflammation and cancer: Lost in the link. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2017;132:77-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Sun Q, Xing X, Wang H, Wan K, Fan R, Liu C, Wang Y, Wu W, Wang Y, Wang R. SCD1 is the critical signaling hub to mediate metabolic diseases: Mechanism and the development of its inhibitors. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;170:115586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Espericueta V, Manughian-Peter AO, Bally I, Thielens NM, Fraser DA. Recombinant C1q variants modulate macrophage responses but do not activate the classical complement pathway. Mol Immunol. 2020;117:65-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Medina KL. Flt3 Signaling in B Lymphocyte Development and Humoral Immunity. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:7289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Elizondo DM, Andargie TE, Marshall KM, Zariwala AM, Lipscomb MW. Dendritic cell expression of ADAM23 governs T cell proliferation and cytokine production through the α(v)β(3) integrin receptor. J Leukoc Biol. 2016;100:855-864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Günzel D, Yu AS. Claudins and the modulation of tight junction permeability. Physiol Rev. 2013;93:525-569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1046] [Cited by in RCA: 1096] [Article Influence: 84.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Limanaqi F, Biagioni F, Gaglione A, Busceti CL, Fornai F. A Sentinel in the Crosstalk Between the Nervous and Immune System: The (Immuno)-Proteasome. Front Immunol. 2019;10:628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Zhou C, Lu Z, Sun B, Yi Y, Zhang B, Wang Z, Qiu SJ. Peripheral Lymphocytes in Primary Liver Cancers: Elevated NK and CD8+ T Cells and Dysregulated Selenium Metabolism. Biomolecules. 2024;14:222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Abe K, Abe N, Sugaya T, Takahata Y, Fujita M, Hayashi M, Takahashi A, Ohira H. Characteristics of peripheral blood mononuclear cells and potential related molecular mechanisms in patients with autoimmune hepatitis: a single-cell RNA sequencing analysis. Med Mol Morphol. 2024;57:110-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Orr C, Xu W, Masur H, Kottilil S, Meissner EG. Peripheral blood correlates of virologic relapse after Sofosbuvir and Ribavirin treatment of Genotype-1 HCV infection. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20:929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Zhou Q, Ding W, Jiang L, Xin J, Wu T, Shi D, Jiang J, Cao H, Li L, Li J. Comparative transcriptome analysis of peripheral blood mononuclear cells in hepatitis B-related acute-on-chronic liver failure. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Listopad S, Magnan C, Day LZ, Asghar A, Stolz A, Tayek JA, Liu ZX, Jacobs JM, Morgan TR, Norden-Krichmar TM. Identification of integrated proteomics and transcriptomics signature of alcohol-associated liver disease using machine learning. PLOS Digit Health. 2024;3:e0000447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Mulcahy V, Liaskou E, Martin JE, Kotagiri P, Badrock J, Jones RL, Rushbrook SM, Ryder SD, Thorburn D, Taylor-Robinson SD, Clark G, Cordell HJ, Sandford RN, Jones DE, Hirschfield GM, Mells GF. Regulation of immune responses in primary biliary cholangitis: a transcriptomic analysis of peripheral immune cells. Hepatol Commun. 2023;7:e0110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Fernandez-Checa JC, Torres S, Garcia-Ruiz C. HILPDA, a new player in NASH-driven HCC, links hypoxia signaling with ceramide synthesis. J Hepatol. 2023;79:269-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Tian M, Hou J, Liu Z, Li Z, Huang D, Zhang Y, Ma Y. BNIP3 in hypoxia-induced mitophagy: Novel insights and promising target for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2024;168:106517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Barchetta I, Cimini FA, Sentinelli F, Chiappetta C, Di Cristofano C, Silecchia G, Leonetti F, Baroni MG, Cavallo MG. Reduced Lipopolysaccharide-Binding Protein (LBP) Levels Are Associated with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) and Adipose Inflammation in Human Obesity. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:17174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Dinarello CA. Overview of the IL-1 family in innate inflammation and acquired immunity. Immunol Rev. 2018;281:8-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1134] [Cited by in RCA: 1386] [Article Influence: 173.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Tamiya T, Kashiwagi I, Takahashi R, Yasukawa H, Yoshimura A. Suppressors of cytokine signaling (SOCS) proteins and JAK/STAT pathways: regulation of T-cell inflammation by SOCS1 and SOCS3. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:980-985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 279] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Sonar S, Lal G. Role of Tumor Necrosis Factor Superfamily in Neuroinflammation and Autoimmunity. Front Immunol. 2015;6:364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Alba MM, Ebright B, Hua B, Slarve I, Zhou Y, Jia Y, Louie SG, Stiles BL. Eicosanoids and other oxylipins in liver injury, inflammation and liver cancer development. Front Physiol. 2023;14:1098467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Bryant CE. Rethinking Toll-like receptor signalling. Curr Opin Immunol. 2024;91:102460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Kram M. Galectin-3 inhibition as a potential therapeutic target in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis liver fibrosis. World J Hepatol. 2023;15:201-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 49. | Zhong Y, Zhang X, Chong W. Interleukin-24 Immunobiology and Its Roles in Inflammatory Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Zhang Y, Wang Z, Wang Y, Jin W, Zhang Z, Jin L, Qian J, Zheng L. CYP3A4 and CYP3A5: the crucial roles in clinical drug metabolism and the significant implications of genetic polymorphisms. PeerJ. 2024;12:e18636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Seillier C, Hélie P, Petit G, Vivien D, Clemente D, Le Mauff B, Docagne F, Toutirais O. Roles of the tissue-type plasminogen activator in immune response. Cell Immunol. 2022;371:104451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Fu C, Li Q, Zou J, Xing C, Luo M, Yin B, Chu J, Yu J, Liu X, Wang HY, Wang RF. JMJD3 regulates CD4 T cell trafficking by targeting actin cytoskeleton regulatory gene Pdlim4. J Clin Invest. 2019;129:4745-4757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Ke Y, Liu X, Sun Y. Regulatory mechanisms of connexin26. Neuroscience. 2025;570:9-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Jee YM, Lee JY, Ryu T. Chronic Inflammation and Immune Dysregulation in Metabolic-Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease Progression: From Steatosis to Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Biomedicines. 2025;13:1260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Petagine L, Zariwala MG, Patel VB. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Immunological mechanisms and current treatments. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:4831-4850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 56. | Barberis M, Rojas López A. Metabolic imbalance driving immune cell phenotype switching in autoimmune disorders: Tipping the balance of T- and B-cell interactions. Clin Transl Med. 2024;14:e1626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Daryabor G, Atashzar MR, Kabelitz D, Meri S, Kalantar K. The Effects of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus on Organ Metabolism and the Immune System. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 336] [Article Influence: 56.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Daskalaki MG, Lapi I, Hurst AE, Al-Qahtani A, Vergadi E, Tsatsanis C. Epigenetic and metabolic regulation of macrophage responsiveness and memory. J Immunol. 2025;vkaf135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Zarghamravanbakhsh P, Frenkel M, Poretsky L. Metabolic causes and consequences of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Metabol Open. 2021;12:100149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Gong J, Tu W, Liu J, Tian D. Hepatocytes: A key role in liver inflammation. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1083780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Cebi M, Yilmaz Y. Immune system dysregulation in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: unveiling the critical role of T and B lymphocytes. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1445634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Zheng D, Liwinski T, Elinav E. Interaction between microbiota and immunity in health and disease. Cell Res. 2020;30:492-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 789] [Cited by in RCA: 2572] [Article Influence: 428.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/