Published online Dec 27, 2025. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v17.i12.113157

Revised: September 3, 2025

Accepted: November 26, 2025

Published online: December 27, 2025

Processing time: 132 Days and 1.7 Hours

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pseudocysts are uncommon complications of ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunts, usually occurring within 3 weeks to 10 years of inser

A 42-year-old man with spina bifida and prior VP shunt insertion was admitted for urinary tract infection, later developing recurrent symptomatic perihepatic fluid collections. Extensive hepatic, cardiac, and surgical evaluations were unre

Persistent diagnostic uncertainty requires broad clinical suspicion and selective testing to identify rare causes of ascites.

Core Tip: Recurrent perihepatic “ascites” in a patient with spina bifida was resistant to exhaustive hepatic, cardiac, and surgical evaluation. The eventual diagnosis—a cerebrospinal fluid pseudocyst from a 27-year-old ventriculoperitoneal shunt—was made possible by renewed clinical suspicion and targeted beta-2 transferrin testing, despite the shunt being invisible on imaging. This case highlights the need to keep rare diagnoses in mind when standard workups fail, and the role of selective, specific tests in solving complex diagnostic puzzles.

- Citation: Quek SXZ, Ching KWJ, Mangat K, Low HC, Ko SQ. Cerebrospinal fluid pseudocyst presenting as ascites: A case report. World J Hepatol 2025; 17(12): 113157

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v17/i12/113157.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v17.i12.113157

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pseudocysts are rare complications of ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunts, typically presenting within 3 weeks to 10 years after insertion[1]. Standard management involves imaging-guided drainage and shunt re

Recurrent abdominal distention associated with vomiting, following an admission for urinary tract infection.

The patient first presented with fever with hematuria and diagnosed with a urinary tract infection with an early prostatic abscess. Two weeks into his intravenous antibiotic course, he developed symptomatic abdominal distention associated with non-bilious, non-bloody vomiting.

He had a history of spina bifida, which was complicated by bilateral congenital talipes equinovarus and neurogenic bladder with vesicoureteral reflux. He had multiple urological revision procedures over 20 years, the most recent being a total cystectomy and revision of ureteroileal conduit at age 32. He had a long-term suprapubic catheter that was com

He had no significant family history of note.

Examination revealed a distended abdomen with mild tenderness but no signs of peritonism. Bowel sounds were active, and there was no succussion splash. No clinical stigmata of chronic liver disease were observed.

No special notes.

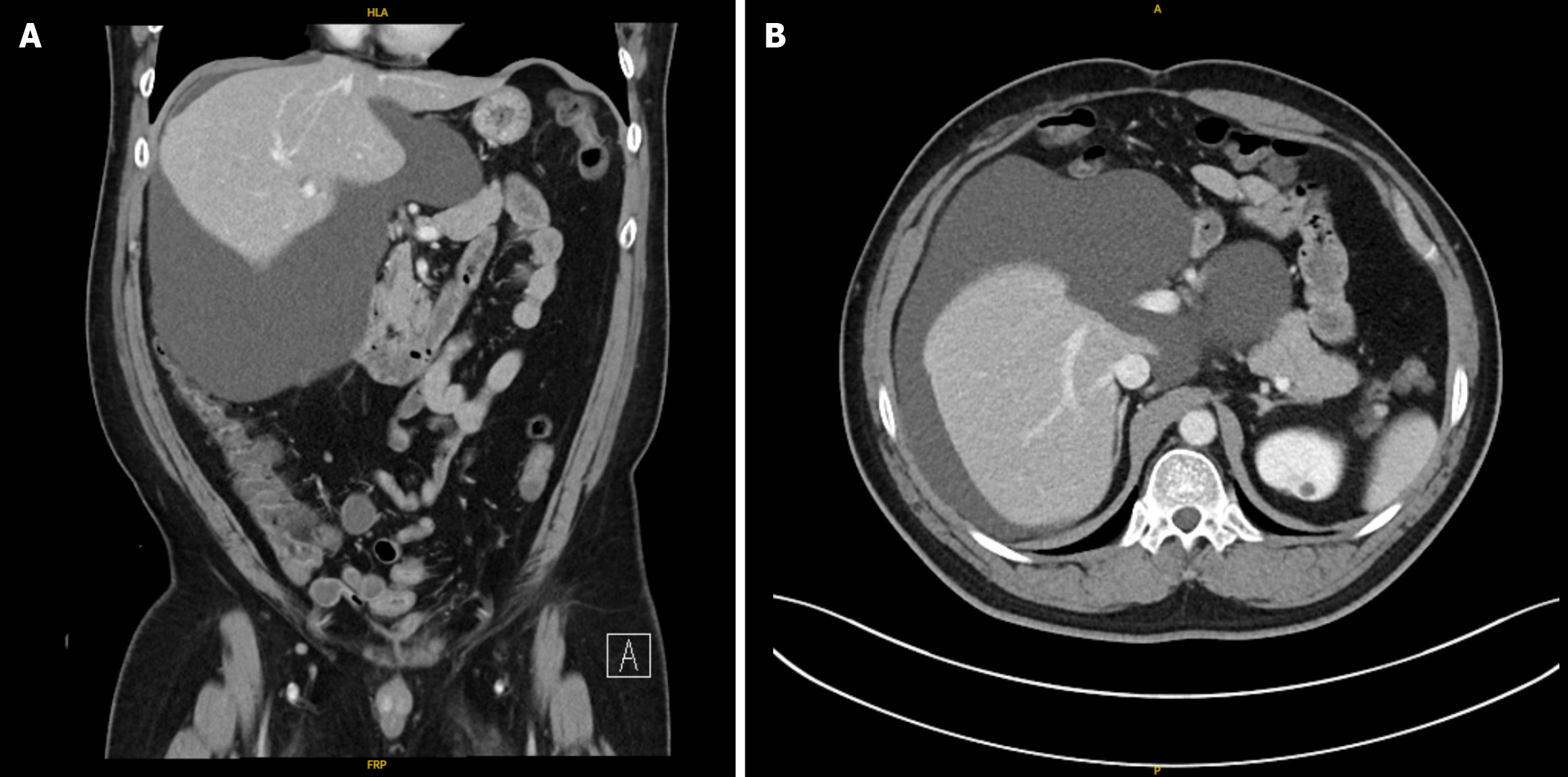

A computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis (CTAP) was performed and revealed a perihepatic fluid collection in the right upper quadrant measuring approximately 17.4 cm × 18.0 cm × 15.6 cm (Figure 1) with mass effect on adjacent structures. Imaging of the liver demonstrated reduced attenuation suggestive of fatty change. The imaged pancreas, spleen, biliary tree, and hepatic and portal veins revealed no focal abnormalities.

The patient underwent radiologically guided percutaneous drainage of the fluid collection, which drained clear colorless fluid (Figure 2). Diagnostic analysis of the fluid studies demonstrated low total protein (< 8 g/L); normal lactate dehydrogenase (61 U/L); and a nucleated cell count of 12/μL with a differential count of 47% lymphocytes, 46% mono

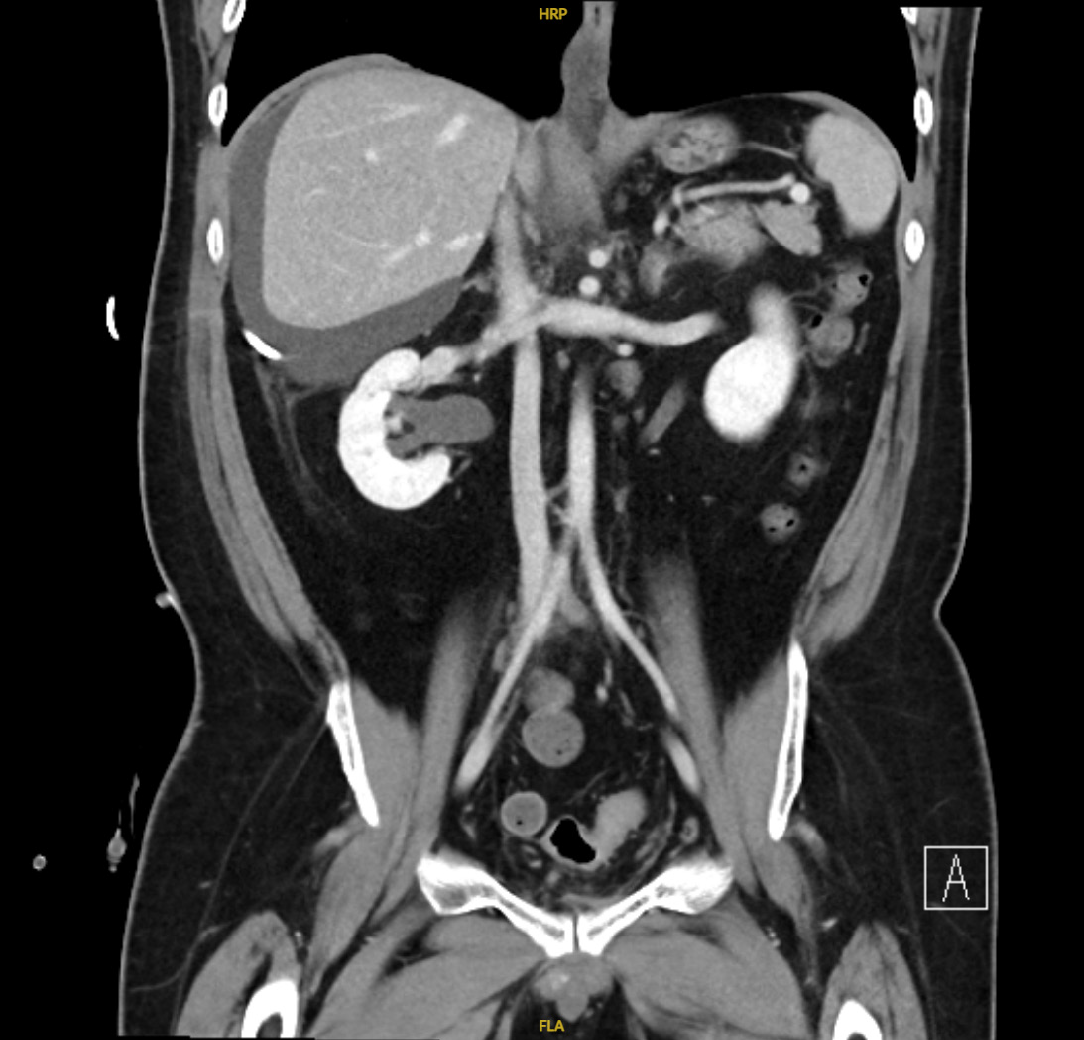

A total of 5.5 L of abdominal fluid was drained over 7 days, and the drain was removed as there was decreasing output. However, 5 days after removal of the abdominal drain, the patient reported increasing abdominal distention. Interval imaging revealed a slightly larger perihepatic collection measuring 18.0 cm × 18.2 cm × 19.0 cm with no other abdominopelvic collections identified (Figure 3). In view of persistent symptomatic abdominal distension, radiologically guided percutaneous drainage was arranged 3 weeks after removal of his first drain. Ten days following the second drain insertion, the patient again reported persistent abdominal distention with minimal drain output. He then underwent a drain exchange and insertion of a third drain. The interventional radiologist noted that the collection was septated, hence a single drain was insufficient to completely drain the collection. Over the 3 months where there were ongoing investigations to ascertain the cause of the peri-hepatic fluid collection, the patient had a total of six percutaneous drain insertions and two drain exchanges.

The patient underwent extensive Investigations for a high SAAG fluid collection, initial differentials being liver cirrhosis or non-cirrhotic portal hypertension (e.g., right heart failure or veno-occlusive disease).

A transient elastography demonstrated liver stiffness of 12.9 kpa (F4 if assuming etiology as fatty liver). Transjugular hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) measurements showed a hepatic vein wedge and free venous pressure of 21 mmHg and 16 mmHg respectively, giving a HVPG of 5 mmHg (normal range). Liver biopsy showed mild mixed macro and microvascular steatosis with steatohepatitis, portal-periportal inflammation, portal-periportal fibrosis with septal linkage, and ground-glass hepatocytes with graded severity of F3 fibrosis.

Transthoracic echocardiography revealed normal left and right ventricular systolic function and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction of 65%. Percutaneous direct portal venogram demonstrated no obstruction to vessel hemodynamics, and flow direction was not suggestive of portal hypertension.

Other surgical causes of a fluid collection were also investigated. Abdominal fluid creatinine and serum creatinine were identical at 55 μmol/L, ruling out an urinoma.

In view of the unyielding diagnostic evaluations, a multidisciplinary discussion was conducted. Significance was drawn to the clear colorless nature of the peri-hepatic fluid, raising the possibility of a CSF pseudocyst. Preceding this discussion, the patient was not known by the managing medical team to have a VP shunt, as it was not stated in the patient’s case notes, nor was it deemed a relevant component of the history at presentation. Furthermore, the VP shunt was not visualized on the initial imaging scans. Specific history elucidated from the patient revealed that the VP shunt was inserted prior to 1995 (over 27 years ago). In consultation with our neurosurgical colleagues, a beta-2 transferrin was sent from the drained fluid which returned positive.

Re-evaluation of the initial CTAP imaging that had been performed, and a specific X-ray VP shunt series did not demonstrate presence of the shunt within the pseudocyst.

Nonetheless, the patient consented for and underwent a VP shunt exploration and revision surgery. Intraoperative findings revealed a calcified catheter and burr hole mounted ventricular catheter with good clear CSF flow at the ventricular end. The distal straight catheter was cut off with a new connector applied and the shunt was eventually re-sited into the pleural space.

Drain output of the remaining abdominal drain was 250 mL on the day of operation, this decreased rapidly with only blood stained fluid in the drain tubing on postoperative day (POD) 1 and having no further output on POD2. Within a week, the patient’s abdominal distention was resolved. He did initially experience pleuritic chest discomfort after the re-siting of the shunt into the pleural space, but this gradually resolved. There were no other postoperative complications. An interval CTAP performed 5 days after the VPS revision surgery demonstrated a reduction in the peri-hepatic collection with only a thin sliver seen.

At three years of follow-up in 2025, there has been no re-accumulation of fluid, supporting the long-term success of the surgical management.

The diagnostic approach to this case covered an extensive investigation to an abdominal fluid collection. Conventional evaluation of ascites typically includes cross-sectional imaging to assess for perforation, malignancy, or infection, alongside fluid analysis (cell count, gram stain, culture, albumin for SAAG, and cytology). In tuberculosis (TB)-endemic regions, TB studies are often added. Visual inspection of the fluid may also provide clues, such as the clear, water-like appearance in this case. In our patient, standard investigations were unrevealing. Fluid studies have shown transudative ascites with no evidence of infection or malignancy. Evaluation for cirrhosis and portal hypertension, including transient elastography, transjugular liver biopsy with HVPG measurement, echocardiography, and portal venography, were all unremarkable. This prolonged diagnostic uncertainty highlights the importance of maintaining a broad differential and considering alternative sources such as urine, bile, or CSF when conventional causes are excluded. A more detailed medical history may also have raised suspicion sooner, given the patient’s remote history of ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement.

A VP shunt may be inserted in patients with hydrocephalus secondary to intracranial tumors, congenital malformations (e.g., spina bifida), meningoencephalitis, intracranial hemorrhage etc.[3]. CSF pseudocyst is a known but uncommon complication of VPS with a complication rate of < 1%-4.5%[1]. It presents more commonly within 3 weeks up to 10 years from insertion, with the longest reported onset being 21 years[4]. The paediatric population more commonly presents with symptoms of elevated intracranial pressure, whereas the adult population predominantly presents with abdominal symptoms such as pain and distension[5-8]. In the literature, the diagnosis is typically made by imaging (ultrasound or CT) showing distal tip of the VPS within a homogeneous intraperitoneal collection[6,7].

Our patient was unique in several ways. First, his VP shunt was inserted at least 27 years ago (it was present prior to the first records we have in 1995), making this the longest reported interval between shunt insertion and the development of a CSF pseudocyst, exceeding the 21-year interval described by Tamura et al[4]. This case therefore underscores the potential for very delayed onset of this complication.

Second, because of his complex surgical history and recurrent urinary tract infections, his pseudocyst was loculated requiring multiple drains for symptomatic relief. Therefore, though radiologically guided drainage has been proposed as a management option, it was not effective for our patient[2].

Third, although imaging usually plays a key role in the diagnosis of such a complication, our patient’s VP shunt could not be seen on the multiple CT scans he underwent, during the ultrasound-guided abdominal drain insertions, or in the dedicated XR VP shunt series[9,10], further obscuring the diagnosis. The suspicion of a CSF pseudocyst had to be confirmed with beta-2 transferrin. Fluid beta-2 transferrin is a protein found in CSF and inner ear perilymph. It has been used in the field of otolaryngology and neurosurgery for diagnosis of CSF leakage[11-15]. Its absence in other bodily fluids makes it a specific test for CSF. It is also sensitive for detecting CSF even at small volumes, with Warnecke et al[16] reporting a test sensitivity of 0.97 and specificity of 0.99 for CSF. In our patient, the assay played a crucial role in providing diagnostic certainty when imaging and routine investigations were inconclusive.

Finally, this case underscores the importance of multidisciplinary collaboration, with care coordinated by the internal medicine team in close partnership with hepatology and radiology, supplemented by input from urology and HPB surgery, and culminating in definitive management by neurosurgery.

Peri-hepatic CSF collection as a result of VPS migration is a rare but important consideration in patients presenting with abdominal distention and fluid accumulation in the peri-hepatic region. Fluid beta-2 transferrin is a useful assay for confirmation of CSF accumulation. Our patient highlights the importance of keeping a broad differential diagnosis in a diagnostic dilemma, especially in a patient with complex medical and surgical history.

| 1. | Aparici-Robles F, Molina-Fabrega R. Abdominal cerebrospinal fluid pseudocyst: a complication of ventriculoperitoneal shunts in adults. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2008;52:40-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kashyap S, Ghanchi H, Minasian T, Dong F, Miulli D. Abdominal pseudocyst as a complication of ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement: Review of the literature and a proposed algorithm for treatment using 4 illustrative cases. Surg Neurol Int. 2017;8:78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fowler JB, De Jesus O, Mesfin FB. Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt. 2023 Aug 23. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Tamura A, Shida D, Tsutsumi K. Abdominal cerebrospinal fluid pseudocyst occurring 21 years after ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement: a case report. BMC Surg. 2013;13:27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rainov N, Schobess A, Heidecke V, Burkert W. Abdominal CSF pseudocysts in patients with ventriculo-peritoneal shunts. Report of fourteen cases and review of the literature. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1994;127:73-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hamid R, Baba AA, Bhat NA, Mufti G, Mir YA, Sajad W. Post ventriculoperitoneal shunt abdominal pseudocyst: Challenges posed in management. Asian J Neurosurg. 2017;12:13-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chung JJ, Yu JS, Kim JH, Nam SJ, Kim MJ. Intraabdominal complications secondary to ventriculoperitoneal shunts: CT findings and review of the literature. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:1311-1317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Achufusi TGO, Chebaya P, Rawlins S. Abdominal Cerebrospinal Fluid Pseudocyst as a Complication of Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt Placement. Cureus. 2020;12:e9363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Goeser CD, McLeary MS, Young LW. Diagnostic imaging of ventriculoperitoneal shunt malfunctions and complications. Radiographics. 1998;18:635-651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wallace AN, McConathy J, Menias CO, Bhalla S, Wippold FJ 2nd. Imaging evaluation of CSF shunts. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202:38-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ryall RG, Peacock MK, Simpson DA. Usefulness of beta 2-transferrin assay in the detection of cerebrospinal fluid leaks following head injury. J Neurosurg. 1992;77:737-739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Skedros DG, Cass SP, Hirsch BE, Kelly RH. Beta-2 transferrin assay in clinical management of cerebral spinal fluid and perilymphatic fluid leaks. J Otolaryngol. 1993;22:341-344. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Meurman OH, Irjala K, Suonpää J, Laurent B. A new method for the identification of cerebrospinal fluid leakage. Acta Otolaryngol. 1979;87:366-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Nandapalan V, Watson ID, Swift AC. Beta-2-transferrin and cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhoea. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1996;21:259-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Haft GF, Mendoza SA, Weinstein SL, Nyunoya T, Smoker W. Use of beta-2-transferrin to diagnose CSF leakage following spinal surgery: a case report. Iowa Orthop J. 2004;24:115-118. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Warnecke A, Averbeck T, Wurster U, Harmening M, Lenarz T, Stöver T. Diagnostic relevance of beta2-transferrin for the detection of cerebrospinal fluid fistulas. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:1178-1184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/