Published online Dec 27, 2025. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v17.i12.112835

Revised: September 10, 2025

Accepted: November 13, 2025

Published online: December 27, 2025

Processing time: 141 Days and 3.2 Hours

Inhibition of liver fibrosis plays a crucial role in curbing the advancement of chronic disease to cirrhosis and even liver cancer. However, modern medicine currently lacks direct anti-fibrotic drugs. He-He-Shu-Yang formula (HHSY) is a renowned Chinese medicine for the treatment of liver fibrosis. However, its mechanism of action has not been fully unraveled.

To explore the efficacy and mechanism of action of HHSY through in vitro and in vivo experiments.

A liver fibrosis rat model (carbon tetrachloride-induced) was treated with low- or high-dose HHSY (10.42 g/kg or 20.84 g/kg) or with colchicine (1 mg/kg) for 9 weeks. In vitro, LX-2 human hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) were activated using transforming growth factor-β1 and subsequently treated with HHSY-containing serum or a nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase 4 (NOX4) inhibitor. Through high-performance liquid chromatography, histopathology (hematoxylin and eosin, Masson), immunohistochemistry, western blot, and quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction analyses, we demonstrated that HHSY inhibited HSC activation and suppressed the NOX4/reactive oxygen species (ROS)/nucleotide binding oligomerization domain-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) pathway.

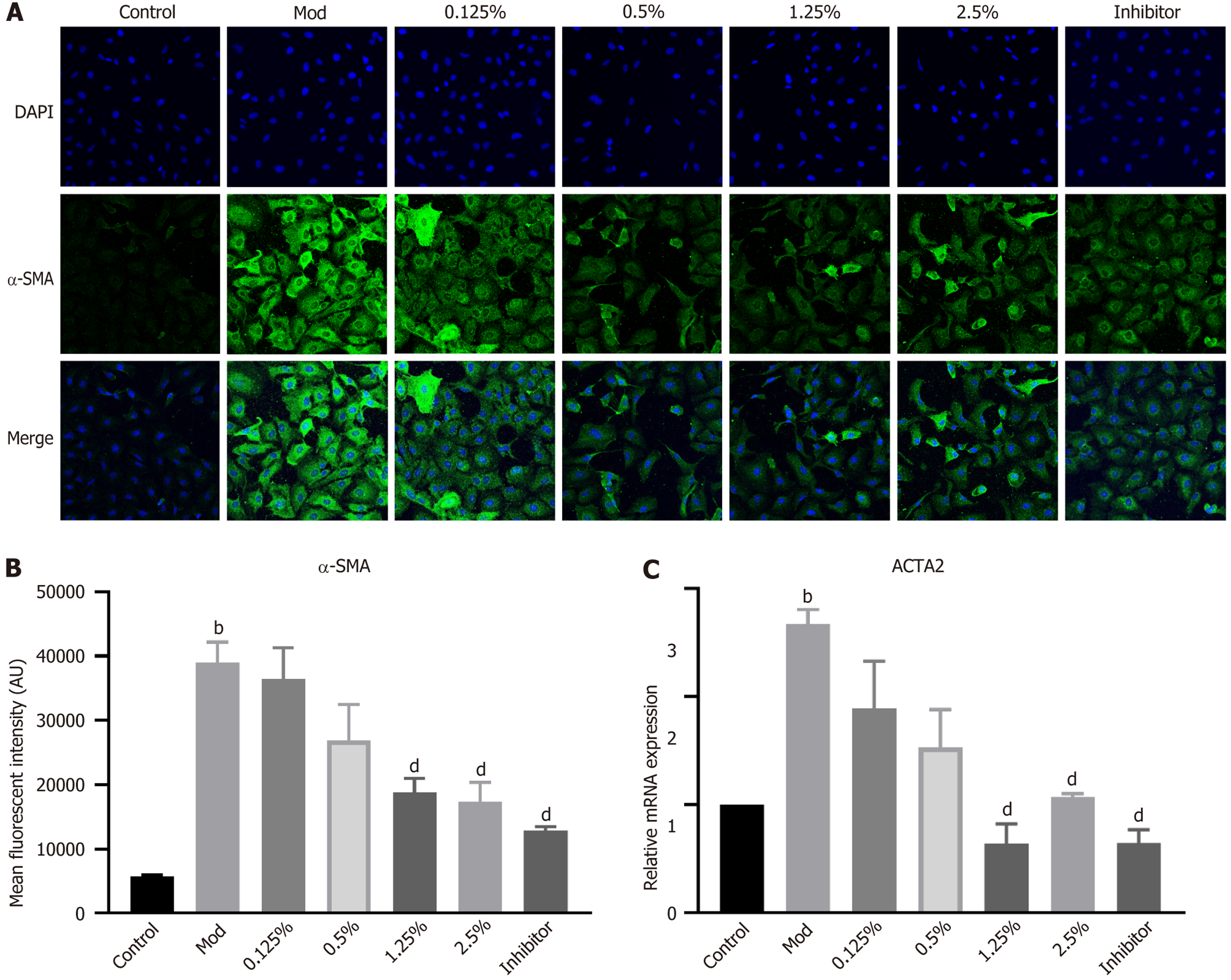

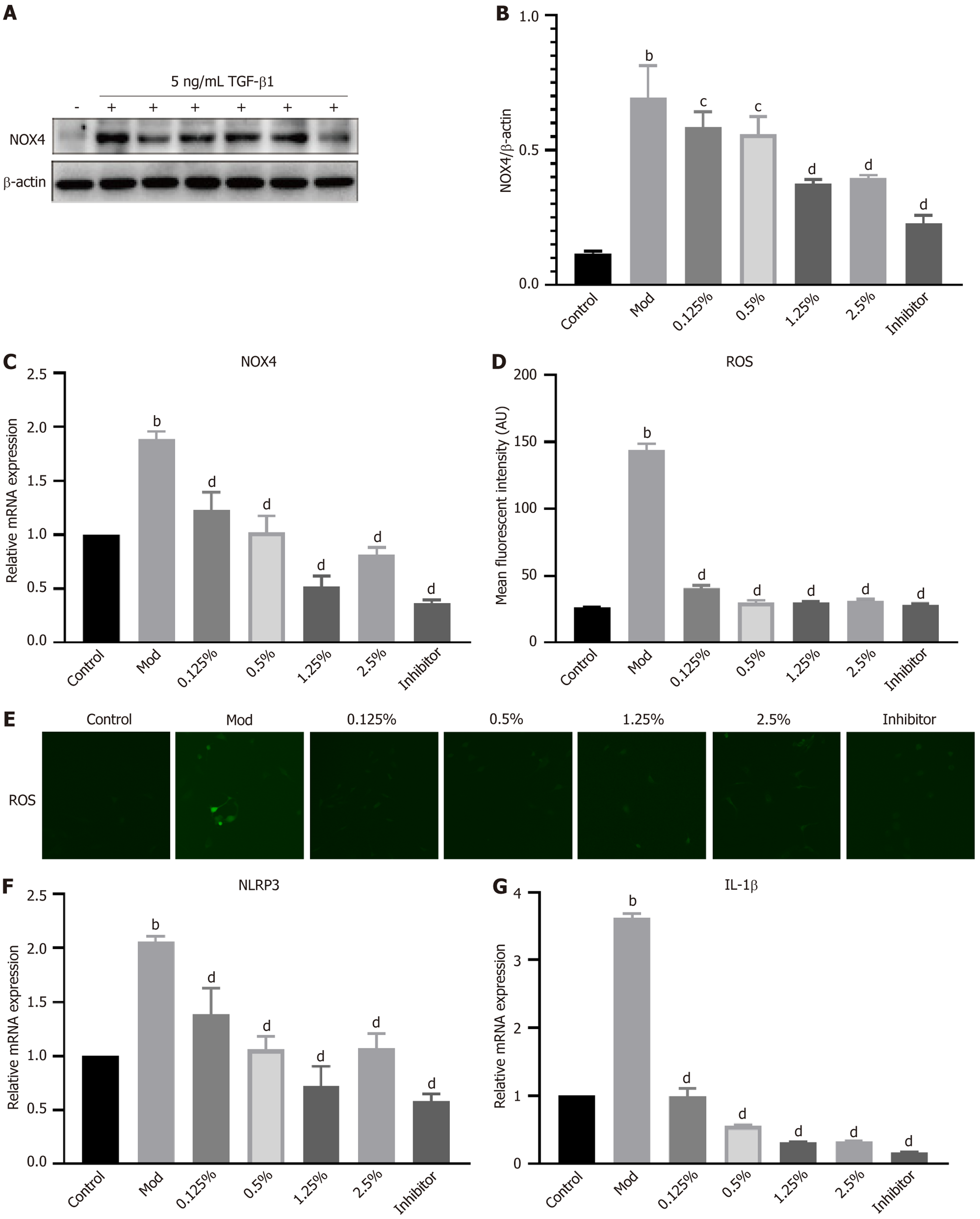

In vivo, HHSY improved liver function and alleviated liver pathology, including reducing inflammatory cell infiltration, and liver fibrosis in carbon tetrachloride rats. with more significant effects at higher doses. Immunohistochemistry revealed that HHSY could decrease alpha-smooth muscle actin, NOX4, and NLRP3 expression, as well as serum ROS levels (O2– and H2O2, P < 0.05). Western blot analysis confirmed HHSY also reduced NLRP3 protein levels (P < 0.05). In vitro, HHSY at 1.25% or 2.5% reduced the levels of ACTA2 mRNA, NOX4 protein and NOX4 mRNA, ROS production, and NLRP3 and IL-1β mRNA in activated LX-2 cells (P < 0.05).

HHSY effectively treats liver fibrosis, likely by inhibiting HSC activation through the NOX4/ROS/NLRP3 path

Core Tip: High-performance liquid chromatography identified six key components in He-He-Shu-Yang formula (HHSY) that are effective in reducing liver fibrosis. HHSY has a definite therapeutic effect on liver fibrosis in vivo and in vitro models. HHSY’s mechanism may be through the inhibition of hepatic stellate cell activation via the nicotinamide adenine dinu

- Citation: Zeng FL, Shi MJ, Mo YS, Xiao HM, Xie YB, Chi XL. He-He-Shu-Yang formula alleviates liver fibrosis by inhibiting hepatic stellate cell activation in vivo and in vitro. World J Hepatol 2025; 17(12): 112835

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v17/i12/112835.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v17.i12.112835

Chronic liver disease is a significant global health issue, as it can progress to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. In 2021, approximately 1.7 billion patients suffered from chronic liver disease worldwide, with deaths of 1.4 million[1]. Liver fibrosis constitutes an obligate pathological stage in chronic liver disease progression. Preventing liver fibrosis helps decrease the occurrence of cirrhosis and liver cancer, as well as the mortality rate of chronic liver disease. However, liver fibrosis is complex because it involves the accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) in the liver and the continuous cross-linking of many components in the ECM, and cross-linked ECM is difficult to degrade[2]. Therefore, current the

In recent years, numerous studies have validated the efficacy of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) in managing liver fibrosis[3-5]. Nevertheless, the mechanism of action of TCM in liver fibrosis has not been fully unraveled because of the complexity of TCM preparations. This greatly hinders the development of novel anti-fibrotic TCM drugs. Thus, there is an urgent need to clarify the molecular mechanisms underlying both hepatic fibrogenesis and TCM’s therapeutic mech

The He-He-Shu-Yang formula (HHSY) has been used clinically for more than 30 years and has demonstrated considerable anti-fibrotic effects in both clinical[6] and experimental studies[7]. It is most commonly prescribed for liver fibrosis or cirrhosis associated with chronic viral hepatitis, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, and alcoholic liver disease. According to TCM theory, HHSY soothes the liver, strengthens the spleen, promotes blood circulation, and removes blood stasis. Animal studies have also shown that HHSY alleviates liver fibrosis[7]; however, its mechanism remains unclear.

Hepatic stellate cell (HSC) activation plays a crucial role in the progression of liver fibrosis[8]. Chronic liver injury induces HSC activation, leading to excessive ECM production, which in turn promotes the development of liver fibrosis[9-11]. Reduced function of the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase (NOX) group and oxidative stress triggered by reactive oxygen species (ROS) play a crucial role in the progression of hepatic fibrosis. NOX4 facilitates the generation of ROS[12], which in turn can trigger downstream P38 mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylation[13], ultimately driving the activation of HSCs in the process of liver fibrosis. Additionally, ROS derived from NOX4 can serve as a second messenger to activate nucleotide binding oligomerization domain-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasomes[14], leading to the cleavage of caspase-1 and activation of the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin (IL)-1β. Moreover, the secretion of IL-18 exacerbates liver inflammation and damage, thereby activating HSCs to promote the onset and development of liver fibrosis[15].

Based on these findings, we hypothesized that HHSY alleviates liver fibrosis by inhibiting HSC activation through the NOX4/ROS/NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. To test this hypothesis, we established a liver fibrosis rat model using carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) and an HSC activation model by stimulating LX-2 cells with transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1). Both in vivo and in vitro experiments were conducted to evaluate the effects of HHSY on HSC activation and the associated signaling pathway. These results provide an experimental basis for the clinical application of HHSY.

Male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats, aged 6 weeks and weighing 110-130 g, were obtained from the Animal Centre of Southern Medical University (Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, China; Animal certificate No. 44002100026384). All rats were housed in a controlled environment (22-24 °C, 40%-45% humidity, 12-hour light/dark cycle) and were given ad libitum access to food and water. All experiments involving animals were conducted according to the United States guidelines for the use and welfare of laboratory animals (National Institutes of Health No. 85-23, as amended in 1985) and the ARRIVE 2.0 guidelines, with approval from the Animal Ethics Committee of Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine, approval No. 2020 064.

HHSY is comprised of elements, such as Bupleurum chinense DC. (Chai-hu), Aurantii Fructus (Zhi-qiao), Astragalus membranaceus (Huang-qi), Paeonia lactiflora Pall (Bai-shao), and Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge (Dan-Shen), that were purchased from Kangmei or Zisun Medical Company (Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, China). The HHSY extract was prepared as follows: All herbs were soaked in six times the volume of deionized ultrapure water for 30 minutes and then decocted for 1 hour two times. The extraction solutions were combined and filtered into a 2-L beaker. The filtrated extract was concentrated to 2.084 g/mL using an R2005KB rotary evaporator (Senco, Shanghai, China) at approximately 65 °C, aliquoted, and stored at -20 °C. For quality control of HHSY, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) fing

LX-2 human HSCs (BNCC341818; BeiNa Biological Company) were seeded at a density of 3.6 × 104 cells/cm2 in 6-well plates. They were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, C11995500BT; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. Before the experiment, LX-2 cells were starved in DMEM without fetal bovine serum for 12 hours. To induce HSC activation, LX-2 cells were stimulated with 5 ng/mL TGF-β1 for 24 hours. Cells were divided into seven groups: Control (fresh DMEM), model (5 ng/mL TGF-β1), HHSY serum (5 ng/mL TGF-β1 + serum containing 0.125%, 0.5%, 1.25%, 2.5%, or 5% HHSY), and NOX4 inhibitor (5 ng/mL TGFβ1 + 10 nM GKT137831), with each treatment administered for 24 hours. All experiments were performed with three biological replicates and three technical replicates per biological replicate, re

Based on preliminary experimental results, the hepatic fibrosis model was established by intraperitoneally injecting SD rats with 30% CCl4 in olive oil (3:7 v/v; 10 mL/kg body weight) every 3 days for 9 weeks. Fifty SD rats were randomly divided into the following five groups (n = 10 rats/group): Control, model, Low-dose HHSY (HHSY-L), High-dose HHSY (HHSY-H), and colchicine. Rats in the control group were intraperitoneally injected with olive oil (1 mL/kg) every 3 days for 9 weeks, whereas those in the other groups were injected with 30% CCl4 in olive oil as mentioned above. The day after injection, rats in the control and model groups were administered 0.1 mL/kg distilled water via orogastric gavage once daily for 9 weeks, whereas those in the HHSY-L and -H groups were given 10.42 g/kg and 20.84 g/kg HHSY, res

After the rats were euthanized by intraperitoneal injection of 10% chloral hydrate (freshly prepared) at a dose of 3.5 mL/kg, their livers were collected, and the liver index was calculated by dividing the wet weight of the liver by the body weight, multiplied by 100%. Serum was prepared from rat abdominal aorta blood via centrifugation at 3000 rpm (15 minutes, 4 °C). Serum levels of alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) were measured via an automatic biochemical analyzer (cobas 6000, Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). Liver tissues were cut into 15’ 15’ 5-mm blocks, which were fixed with 10% formalin, processed using routine histopathological techniques, and sliced into 4-mm sections. The sections were deparaffinized with xylene and rehydrated with 100% ethanol for 5 min, followed by 80% ethanol for another 5 minutes. Then, the sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin staining kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) and Masson trichrome stain (Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The sections were imaged using an optical microscope at a magnification of 200’ and assessed in a blinded manner by two independent third-party pathologists who were unaware of the treatment assignments.

Sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated using standard protocols, permeabilized in 0.4% Triton X-100 and 1% bovine serum albumin for 2 hours, and incubated with the following primary antibodies at 4 °C for 72 hours: Anti-α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) antibody (ab7817,Abcam, Cambridge, MA, United States; diluted 1:10000 in 1% bovine serum albumin dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline, NOX4 antibody (ab133303, Abcam; diluted 1:2000), NLRP3 antibody (ab263899, Abcam; diluted 1:500). Following the wash step, the slices were exposed to secondary antibodies at a temperature of approximately 25 ± 2 °C for a duration of 2 hours. The secondary antibody used was a highly sensitive horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse/rabbit IgG polymer (Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology, dilution 1:500). Subsequently, the segments underwent a washing process, were dried, and were positioned onto slides. The sections were observed at × 200 magnification using a Leica confocal microscope and stained cells in a random microscopic field were counted. α-SMA expression was semi-quantitatively analyzed by measuring the average optical density (AOD) using the ImageJ software (version 1.53, NIH, Bethesda, MD, United States). Antibody against Col1A1 (1:200; sc2597; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, United States) was used for immunohistochemistry (IHC) via the Envision two-step procedure in SD rats with CCl4-induced liver fibrosis. Cytoplasmic deposition of granules with a brownish-yellow hue indicated Col1A1 expression.

LX-2 cells grown on coverslips were induced with TGF-β1 (5 ng/mL) for 24 hours, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and incubated with anti-α-SMA antibody (diluted 1:200, 14395-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Wuhan, Hubei Province, China) at

Liver tissues were homogenized in a 1% phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Sigma-Aldrich, Solarbio)-containing radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (Beyotime, Thermo Fisher Scientific) with phosphatase inhibitors (Roche; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, United States). Proteins (20 μg per lane) were resolved using 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Merck, IPVH00010). The membranes were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin, incubated with primary antibodies (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology) at 4 °C overnight including anti-NOX4 (ab133303,Abcam; diluted 1:2000), anti-NLRP3 (ab263899, Abcam; diluted 1:500) and anti-Caspase1 (sc-56036, Santa Cruz Biotechnology; diluted 1:1000). After washing with Tris- buffered saline, the membranes were incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies at room temperature for 2 hours. Blots were developed with Clarity ECL (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, United States) and imaged using ChemiDoc Touch Imaging System. Band intensities were analyzed using ImageLab software (v6.1, Bio-Rad Laboratories), with β-actin as an internal control.

Total RNA was isolated from various types of cells and tissues using TRIzol Reagent and quantified using a Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer. cDNA was synthesized using a reverse transcription kit (lot No. RR360A; Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan). Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed using a SYBR Green kit (RR820A; Takara Bio) in an ABI PRISM 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific). The thermal cycling program was as follows: Initial denaturation at 95 °C for 15 minutes, followed by 40 cycles at 95 °C for 15 seconds, 60 °C for 60 seconds, and 72 °C for 10 minutes. Relative target gene expression was quantified using the 2-ΔΔt method, using the housekeeping gene GAPDH as a reference gene. Primers were designed using ABI Primer Express 3.0 and synthesized at Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China (Table 1).

| Target gene | Primer | Sequence (5’-3’) |

| NLRP3 | Forward primer | 5’-GCTTGCCGACGATGCCTTCC-3’ |

| Reverse primer | 5’-GCTGTCATTGTCCTGGTGTCTTCC-3’ | |

| ACTA2 | Forward primer | 5’-TCGTGCTGGACTCTGGAGATGG-3’ |

| Reverse primer | 5’-CCACGCTCAGTCAGGATCTTCATG-3’ | |

| NOX4 | Forward primer | 5’-TCACAGCCTCTACATATGCAAT-3’ |

| Reverse primer | 5’-CAGCAGCATGTAGAAGACAAAG-3’ | |

| CASP1 | Forward primer | 5’-GAAGAAACACTCTGAGCAAGTC-3’ |

| Reverse primer | 5’-GATGATGATCACCTTCGGTTTG-3’ | |

| IL-1β | Forward primer | 5’-GCCAGTGAAATGATGGCTTATT-3’ |

| Reverse primer | 5’-AGGAGCACTTCATCTGTTTAGG-3’ | |

| GAPDH | Forward primer | 5’-GAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTC-3’ |

| Reverse primer | 5’-GAAGATGGTGATGGGATTTC-3’ |

To determine the non-cytotoxic HHSY serum concentration, cell viability was assessed using a Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, C0038, Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). In brief, LX-2 cells were inoculated in a 96-well plate at 5000 cells/well and cultured for 24 hours. After treatment with HHSY at concentrations of 0.125%, 0.5%, 1.25%, 2.5%, and 5% for 24 hours, 10 μL CCK-8 solution was added to each well and the plate was incubated in a constant temperature incubator at 37 °C for 2 hours. The absorbance value at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader. All samples were analyzed at least three times. The optical density (OD) values were measured and cell viability was calculated as follows: Cell viability = (detection well OD value - blank well OD value)/(control well OD value - blank well OD value).

GraphPad Prism 8 software GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, United States) was used for data graphing and statistical analysis. Normal distribution was assessed utilizing the Shapiro-Wilk test and normally distributed data are reported as mean ± SD. Means of two groups with a normal distribution and homogeneous variance were analyzed using a two-independent-sample t-test. Analysis of variance was used for multiple groups, accompanied by Tukey’s test for honestly significant differences to evaluate pairwise comparisons. For datasets that do not follow a normal distribution pattern, the results were presented with the median and interquartile range. To assess statistical differences among various groups, the Kruskal-Wallis test was employed, succeeded by Dunn’s post-hoc analysis for examining pairwise contrasts. Statistical significance was set to P < 0.05.

To characterize the HHSY extract, six compounds were identified using HPLC analysis. The main components of the HHSY extract according to the main peaks in the HPLC-ultraviolet chromatogram were identified as paeoniflorin, isoflavone glucoside, glycyrrhizin, naringin, hesperidin, and neohesperidin (Figure 1).

After a 9-week intervention period, the mortality rate among rats was relatively low. Only one death was recorded in each of the model, HHSY-H, and colchicine groups, whereas no deaths were observed in the other groups. Rats in the control group exhibited liveliness, activeness, and prompt reactions. Conversely, rats in the model group displayed decreased activity levels and a preference for remaining motionless and congregating in groups. However, rats in the HHSY-L, HHSY-H, and colchicine groups demonstrated improved activity and responsiveness.

As shown in Figure 2A and B, rats in the model group exhibited a substantial decline in body weight and a marked increase in the liver index. Treatments with HHSY-H and colchicine resulted in greater improvements in body weight compared to the model group, although the differences were not statistically significant. However, compared with the model group, both treatment groups showed a significant reduction in the liver index (Figure 2B). CCl4 model rats exhibited significantly greater increases in serum ALT and AST levels compared to those in the control group (Figure 2C and D). The HHSY-L, HHSY-H, and colchicine treatments significantly decreased the serum ALT and AST levels, with no statistically significant distinction between the HHSY-H and colchicine groups. Histological changes are shown in Figure 2E. Compared to those in the control group, liver tissues from the model group exhibited substantial inflammatory cell infiltration and extensive fibrous tissue proliferation in the portal area and around the central vein. Furthermore, the liver lobule structure was compromised, resulting in the disappearance of liver cords and the formation of pseudolobules. Conversely, fibrotic damage was markedly improved in the treatment groups, with thinner fibrous septa and reduced inflammatory infiltration. Rats in the HHSY-H and colchicine groups exhibited minimal inflammatory cell infiltration and a greater degree of improvement than those in the HHSY-L group. Therefore, only the HHSY-H treatment was selected for subsequent mechanistic experiments.

HHSY treatment effectively suppressed the expression of α-SMA, a marker of HSC activation in the rat liver. IHC staining revealed a limited presence of α-SMA in the liver of rats in the control group (Figure 3A). Conversely, rats in the model group exhibited heightened α-SMA expression in the hepatic sinusoid, portal vein, and portal area. Remarkably, animals in the HHSY and colchicine groups displayed a substantial reduction in α-SMA expression in these areas. The AOD of α-SMA showed a significantly greater increase in the model group compared to the control group (P < 0.001). Compared to that in the model group, both the HHSY and colchicine groups exhibited a significantly greater reduction in α-SMA AOD (P < 0.001; Figure 3B); however, the difference between the two groups was insignificant (P = 0.977).

IHC staining results showed that NOX4 expression (brown area in Figure 4A) was significantly increased by CCl4 treatment, and this increase was significantly suppressed by HHSY and colchicine (Figure 4A). ROS encompass various compounds, including superoxide anions (O2–), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radicals (OH). As shown in Figure 4B-D, serum levels of O2– and H2O2 were strongly increased in the CCl4 model group, whereas the OH clearance rate was decreased. HHSY strongly reduced the serum levels of O2- and H2O2 and enhanced the OH clearance rate. No significant differences were found between the HHSY and colchicine groups. IHC revealed that NLRP3 expression was strongly enhanced in rats in the model group but significantly suppressed in animals in the HHSY and colchicine groups (Figure 4E). Western blot results showed that the protein levels of NLRP3 and caspase-1, which are related to the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway, were significantly increased in the model group. Conversely, the decrease in the expression of these two proteins was significantly more in both the HHSY and colchicine groups than in the model group (Figure 4F).

CCK-8 results showed that, compared with that in the control group, the viability of LX-2 cells exposed to serum containing 0.125%, 0.5%, 1.25%, or 2.5% HHSY was above 90%, with no significant differences among the treatment groups. However, the cell viability of cells treated with serum containing 5% HHSY was significantly reduced. Therefore, in subsequent experiments, HHSY was used at 0.125%, 0.5%, 1.25%, and 2.5%. The alterations were notably more in the cells of the model than in those of the control group, accompanied by a substantial increase in cell proliferation as indicated by the increase in the average fluorescence intensity of α-SMA in immunofluorescence analysis (Figure 5A and B). Treatment with HHSY at 1.25% or 2.5% and NOX4 inhibition resulted in a significantly lower average fluorescence intensity of α-SMA compared to the level in the model group (P < 0.05). ACTA2 mRNA levels assessed using quantitative reverse transcription PCR showed similar alterations as those observed in the immunofluorescence experiments (Figure 5C).

Considering the potential influence of excess NOX4 on HSC activation, we measured NOX4 Levels in TGF-β1-induced LX-2 cells. As anticipated, NOX4 protein and NOX4 mRNA levels increased significantly in response to TGF-β1 stimulation (Figure 6A-C). Importantly, NOX4 accumulation in TGF-β1-induced LX-2 cells was markedly diminished by treatment with HHSY at 1.25% or 2.5% and by NOX4 inhibition. Notably, there was no discernible difference between the 2.5% HHSY group and the NOX4 inhibitor group. The mean fluorescence intensity of ROS in TGF-β1-induced LX-2 cells was notably higher than that in the control group (P < 0.01; Figure 6D and E) but was significantly decreased by 1.25% and 2.5% HHSY and NOX4 inhibition (P < 0.01). Additionally, HHSY and NOX4 inhibition suppressed NLRP3 and IL-1β mRNA levels in LX2 cells induced by TGF-β1 (Figure 6F and G).

In this study, we evaluated the efficacy of HHSY in alleviating liver fibrosis in vivo and in vitro. Our results revealed that HHSY acts by inhibiting HSC activation via the NOX4/ROS/NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. In what follows, we discuss our main findings. First, HPLC for quality control identified six key components in HHSY: Isoflavone glucoside, paeoniflorin, glycyrrhizin, naringin, hesperidin, and neohesperidin. Studies have shown that these six components[16-20] can ameliorate liver injury and fibrosis. Among its components, paeoniflorin[21] has been reported to inhibit HSC activation and reduce ECM deposition both in vivo and in vitro, providing a theoretical basis for HHSY’s anti-fibrotic effects. Consistent with these component-specific findings, our data confirmed that HHSY alleviated liver fibrosis by inhibiting HSC activation. Activated HSCs can transform into myofibroblasts that secrete matrix proteins, thereby driving liver fibrogenesis[11]. Increasing evidence indicates that oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokines can activate HSCs[22], which then produce ECM and promote liver fibrosis. In our CCl4 rat model - where CCl₄ is metabolized to the CCl3 free radical that damages hepatocytes, stimulates inflammatory processes, and activates HSCs - HHSY significantly decreased the liver index, serum ALT and AST levels, inflammatory cell infiltration, and fibrotic tissue proliferation in the liver. These results suggest that HHSY alleviates liver injury and fibrosis. More importantly, HHSY was found to effectively suppress the expression of α-SMA, a marker of HSC activation. In CCl4-induced fibrotic rats, HHSY substantially reduced the α-SMA-positive area in the liver. In vitro, HHSY inhibited TGF-β1-induced LX2 cell activation. Treat

Second, we found that HHSY effectively reduces liver fibrosis by significantly mediating the NOX4/ROS/NLRP3 pathway, revealing a key molecular mechanism of action of HHSY. Liver inflammation and oxidative stress both con

Notably, the promising anti-fibrotic effects of HHSY demonstrated in this study are supported by an ongoing nationwide, multi-center randomized controlled trial in patients with chronic hepatitis B-related liver fibrosis. The translational potential of HHSY is underscored by the clinically achievable doses used in this preclinical model and its multi-target mechanism. Overall, with forthcoming clinical evidence, these findings position HHSY as a strong complementary therapy candidate for chronic hepatitis B-related liver fibrosis.

The research encountered several constraints. In the in vitro experiments, only one cell line, LX-2, was used, and primary HSCs were not used for validation. In future, we plan to carry out experiments with other relevant cells for further verification. In addition, because of time and funding constraints, we did not use NOX4 overexpression or kno

Overall, our findings demonstrate that HHSY improves liver fibrosis in vitro and in vivo by inhibiting HSC activation th

| 1. | Zhao Y, Bo Y, Zu J, Xing Z, Yang Z, Zhang Y, Deng Y, Liu Y, Zhang L, Yuan X, Wang Y, Henry L, Ji F, Nguyen MH. Global Burden of Chronic Liver Disease and Temporal Trends: A Population-Based Analysis From 1990 to 2021 With Projections to 2050. Liver Int. 2025;45:e70155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lyu C, Kong W, Liu Z, Wang S, Zhao P, Liang K, Niu Y, Yang W, Xiang C, Hu X, Li X, Du Y. Advanced glycation end-products as mediators of the aberrant crosslinking of extracellular matrix in scarred liver tissue. Nat Biomed Eng. 2023;7:1437-1454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rong G, Chen Y, Yu Z, Li Q, Bi J, Tan L, Xiang D, Shang Q, Lei C, Chen L, Hu X, Wang J, Liu H, Lu W, Chen Y, Dong Z, Bai W, Yoshida EM, Mendez-Sanchez N, Hu KQ, Qi X, Yang Y. Synergistic Effect of Biejia-Ruangan on Fibrosis Regression in Patients With Chronic Hepatitis B Treated With Entecavir: A Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J Infect Dis. 2022;225:1091-1099. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Xiao HM, Shi MJ, Jiang JM, Cai GS, Xie YB, Tian GJ, Xue JD, Mao DW, Li Q, Yang HZ, Guo H, Lei CL, Lu W, Chen L, Liu HB, Wang J, Gao YQ, Chen JZ, Wu SD, Chen HJ, Zhao PT, Zhang CZ, Ou-Yang WW, Wen ZH, Chi XL. Efficacy and safety of AnluoHuaxian pills on chronic hepatitis B with normal or minimally elevated alanine transaminase and early liver fibrosis: A randomized controlled trial. J Ethnopharmacol. 2022;293:115210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wang T, Jin W, Huang Q, Li H, Zhu Y, Liu H, Cai H, Wang J, Wang R, Xiao X, Zhao Y, Zou W. Clinical Efficacy and Safety of Eight Traditional Chinese Medicine Combined with Entecavir in the Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis B Liver Fibrosis in Adults: A Network Meta-Analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2020;2020:7603410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wang HJ, Wu SD, Chi XL, Xiao HM, Wang YB, Lin ZH. [The regulatory effect of He-He-Shu-Yang formula on immune function in chronic hepatitis B patients with liver depression and spleen deficiency syndrome]. Xin Zhongyi. 2016;48:99-102. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Xiao HM, Wang HJ, Xie YB, Chi XL. [Evaluation of the therapeutic effect of He-He-Shu-Yang Formula on experimental liver fibrosis in rats]. Zhongguo Shiyan Fangjixue Zazhi. 2016;22:132-135. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Schwabe RF, Brenner DA. Hepatic stellate cells: balancing homeostasis, hepatoprotection and fibrogenesis in health and disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;22:481-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bourebaba N, Marycz K. Hepatic stellate cells role in the course of metabolic disorders development - A molecular overview. Pharmacol Res. 2021;170:105739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Caligiuri A, Gentilini A, Pastore M, Gitto S, Marra F. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Liver Fibrosis Regression. Cells. 2021;10:2759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 40.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yan Y, Zeng J, Xing L, Li C. Extra- and Intra-Cellular Mechanisms of Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation. Biomedicines. 2021;9:1014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wan S, Luo F, Huang C, Liu C, Luo Q, Zhu X. Ursolic acid reverses liver fibrosis by inhibiting interactive NOX4/ROS and RhoA/ROCK1 signalling pathways. Aging (Albany NY). 2020;12:10614-10632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Li C, Li L, Yang CF, Zhong YJ, Wu D, Shi L, Chen L, Li YW. Hepatoprotective effects of Methyl ferulic acid on alcohol-induced liver oxidative injury in mice by inhibiting the NOX4/ROS-MAPK pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;493:277-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zhang K, Lin L, Zhu Y, Zhang N, Zhou M, Li Y. Saikosaponin d Alleviates Liver Fibrosis by Negatively Regulating the ROS/NLRP3 Inflammasome Through Activating the ERβ Pathway. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:894981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kim DH, Choi G, Song EB, Lee H, Kim J, Jang YS, Park J, Chi S, Han J, Kim SM, Kim D, Bae SH, Lee HW, Park JY, Kang SG, Cha SH, Han YH. Treatment of IL-18-binding protein biologics suppresses fibrotic progression in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis. Cell Rep Med. 2025;6:102047. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Aobulikasimu N, Zheng D, Guan P, Xu L, Liu B, Li M, Huang X, Han L. The Anti-inflammatory Effects of Isoflavonoids from Radix Astragali in Hepatoprotective Potential against LPS/D-gal-induced Acute Liver Injury. Planta Med. 2023;89:385-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Qu Y, Zong L, Xu M, Dong Y, Lu L. Effects of 18α-glycyrrhizin on TGF-β1/Smad signaling pathway in rats with carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:1292-1301. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Qin MC, Li JJ, Zheng YT, Li YJ, Zhang YX, Ou RX, He WY, Zhao JM, Liu ST, Liu MH, Lin HY, Gao L. Naringin ameliorates liver fibrosis in zebrafish by modulating IDO1-mediated lipid metabolism and inflammatory infiltration. Food Funct. 2023;14:10347-10361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Nasehi Z, Kheiripour N, Taheri MA, Ardjmand A, Jozi F, Shahaboddin ME. Efficiency of Hesperidin against Liver Fibrosis Induced by Bile Duct Ligation in Rats. Biomed Res Int. 2023;2023:5444301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Xu W, Wang L, Niu Y, Mao L, Du X, Zhang P, Li Z, Li H, Li N. A review of edible plant-derived natural compounds for the therapy of liver fibrosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;35:133-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Liu Y, He CY, Yang XM, Chen WC, Zhang MJ, Zhong XD, Chen WG, Zhong BL, He SQ, Sun HT. Paeoniflorin Coordinates Macrophage Polarization and Mitigates Liver Inflammation and Fibrogenesis by Targeting the NF-[Formula: see text]B/HIF-1α Pathway in CCl(4)-Induced Liver Fibrosis. Am J Chin Med. 2023;51:1249-1267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zhou Y, Long D, Zhao Y, Li S, Liang Y, Wan L, Zhang J, Xue F, Feng L. Oxidative stress-mediated mitochondrial fission promotes hepatic stellate cell activation via stimulating oxidative phosphorylation. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13:689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Sergazy S, Shulgau Z, Kamyshanskiy Y, Zhumadilov Z, Krivyh E, Gulyayev A, Aljofan M. Blueberry and cranberry extracts mitigate CCL4-induced liver damage, suppressing liver fibrosis, inflammation and oxidative stress. Heliyon. 2023;9:e15370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Chen L, Zhou T, White T, O'Brien A, Chakraborty S, Liangpunsakul S, Yang Z, Kennedy L, Saxena R, Wu C, Meng F, Huang Q, Francis H, Alpini G, Glaser S. The Apelin-Apelin Receptor Axis Triggers Cholangiocyte Proliferation and Liver Fibrosis During Mouse Models of Cholestasis. Hepatology. 2021;73:2411-2428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Li Y, Zhang Y, Chen T, Huang Y, Zhang Y, Geng S, Li X. Role of aldosterone in the activation of primary mice hepatic stellate cell and liver fibrosis via NLRP3 inflammasome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35:1069-1077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Tseng HF, Chao HN, Lin CH, Kuo CY. Danshensu Attenuates Palmitic Acid-Induced Activation of Hepatic Stellate Cells by Regulating Pyroptosis. Int J Med Sci. 2025;22:1865-1874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/