Published online Nov 27, 2025. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v17.i11.111354

Revised: July 26, 2025

Accepted: October 27, 2025

Published online: November 27, 2025

Processing time: 152 Days and 18.2 Hours

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), formerly known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, represents a growing global health burden, contributing significantly to liver-related morbidity and mortality. Early detection and timely intervention are essential to prevent disease progression. Conventional diagnostic methods, which rely on specialized imaging and inva

Core Tip: Artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning and deep learning, holds transformative potential for the non-invasive diagnosis and risk stratification of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). These AI models utilize readily available clinical data, biomarkers, and imaging modalities (ultrasound, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging) to detect steatosis, predict disease risk, and stage fibrosis with greater accuracy than conventional scoring systems such as fibrosis-4. Despite their promising performance, several challenges hinder widespread clinical adoption, including the need for data standardization, rigorous prospective validation, model interpretability, and seamless integration into existing healthcare workflows. Overcoming these barriers is essential to fully harness AI potential in improving MASLD diagnosis and management.

- Citation: Hegazy MAE. Artificial intelligence in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: Machine learning for non-invasive diagnosis and risk stratification. World J Hepatol 2025; 17(11): 111354

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v17/i11/111354.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v17.i11.111354

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), formerly known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), is the most common chronic liver disorder worldwide, affecting approximately 30% of the general adult popu

Artificial intelligence (AI), particularly machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), has emerged as a promising solution, offering non-invasive, scalable, and accurate tools for the diagnosis, staging, and prognostication of MASLD. AI algorithms can integrate clinical data (e.g., electronic health records), biomarkers, and imaging modalities (e.g., ultrasound, MRI) to outperform traditional risk scores such as the fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index[3]. This mini-review provides a concise yet comprehensive overview of current AI applications in MASLD diagnosis. It also discusses key challenges and limitations in translating AI into clinical practice, including issues related to data privacy, model interpretability, and the need for robust prospective validation. The aim is to inform clinicians, researchers, and policymakers on the practical implications of integrating AI technologies into MASLD management.

Several studies have investigated predictive scoring systems and risk factors for MASLD; however, their findings remain inconsistent and controversial[4,5]. ML offers a promising alternative for identifying optimal predictive models[6], as it enables the algorithms construction that learn from data without being explicitly programmed. Applications of ML in gastroenterology field are steadily expanding[7].

ML algorithms analyze anthropometric, demographic, and biochemical data to predict MASLD risk, and numerous studies have demonstrated their effectiveness through various modeling approaches. Yu et al[3] developed an explainable random forest (RF) model incorporating 10 clinical features, including liver enzymes, body mass index (BMI), and metabolic markers. The model achieved excellent performance, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.928 in internal validation and 0.918 in external cohorts. Among six evaluated ML models, the RF algorithm demonstrated the highest discriminative ability, making it the preferred choice. The final model showed excellent calibration and discrimination, using only routinely collected clinical data.

Another ML approach using support vector machines (SVM) was employed to assess liver fibrosis without relying on elastography or platelet counts, achieving AUCs of 0.886 for ≥ F2 fibrosis, 0.882 for ≥ F3, and 0.916 for cirrhosis detection[8]. Comparative studies by Ahn et al[6] and Spann et al[7] have shown that ML models often outperform conventional risk scores (e.g., FIB-4, APRI) by integrating a broader range of clinical variables.

DL, a subset of AI, is particularly valuable for imaging analysis. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs), a prominent DL architecture, have enhanced the diagnostic accuracy of imaging based MASLD assessment. For instance, CNNs employing transfer learning applied to ultrasound images have achieved an AUC of 0.91 for detecting hepatic steatosis (defined as PDFF ≥ 5%)[9]. Additionally, computed tomography (CT) and MRI have been utilized for DL-based analysis. Yasaka et al[10] demonstrated moderate accuracy in fibrosis staging using a CT-based DL model, although further refinement is needed before widespread clinical application.

AI models in MASLD utilize a wide range of data inputs, including clinical parameters (e.g., body mass index, diabetes status), laboratory results (e.g., liver enzymes, lipid profiles), imaging features (ultrasound, CT, MRI), and histology-confirmed outcomes. The integration of these multimodal data sources enhances predictive accuracy; however, variability in data acquisition remains a significant challenge (Table 1).

| Ref. | AI model | Data used | Key finding | AUC/performance |

| Yu et al[3], 2025 | RF | 50 clinical and biochemical features (e.g., BMI, liver enzymes, metabolic markers); validated against histology or elastography in subsets of cohorts | Developed an explainable 10-feature RF model for MASLD prediction | AUC: 0.928 (internal), 0.918 (external) |

| Wakabayashi et al[8], 2025 | SVM | Clinical and laboratory markers (excluding platelet counts); validated against histology or elastography in subsets of cohorts | Predicted fibrosis stages without platelet count or elastography | AUC: 0.886 (≥ F2), 0.916 (cirrhosis) |

| Byra et al[9], 2022 | CNN (ultrasound) | Applied CNNs to ultrasound images for steatosis detection | Deep learning-based fat quantification using transfer learning | AUC: 0.91 (PDFF ≥ 5%) |

| Yasaka et al[10], 2018 | DL (CT) | Utilized CT-based DL for fibrosis staging; referenced biopsy-confirmed fibrosis stages for model validation | Staged liver fibrosis from CT scans (moderate correlation with histopathology) | Moderate performance (needs improvement) |

AI algorithms that incorporate elastography data have shown improved performance in fibrosis detection by analyzing liver stiffness measurements[11]. Multimodal data integration—combining demographic, clinical, anthropometric, and biochemical variables—enables more accurate population-level risk prediction[2]. AI plays a crucial role in fusing clinical, imaging, and laboratory data to enhance diagnostic precision and improve overall performance of non-invasive asse

While advanced healthcare centers often benefit from automated extraction of data from electronic health records (EHRs) and picture archiving and communication systems (PACS)—including digital imaging and communications in medicine (DICOM) files and laboratory application programming interfaces[2,11]—manual data entry is still required for non-digitized sources such as histopathology reports and calculated clinical scores (e.g., APRI, FIB-4)[8,10]. The adoption of standardized data pipelines, such as Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources for EHRs and AI-ready DICOM annotations, is essential for achieving scalability and real-world integration of AI applications[9].

ML models have demonstrated the ability to predict MASLD progression using longitudinal data. For example, fibrosis prediction using SVM and RF algorithms allows for patient stratification by fibrosis stage, facilitating personalized disease management[8].

Model training and validation are often enhanced through transfer learning techniques. Pretrained CNNs, such as ResNet and VGG, are fine-tuned on liver-specific imaging datasets to improve diagnostic accuracy and reduce computational costs[9].

Integration of AI models into clinical workflows has followed several strategies. In rule-based systems, ML outputs—such as fibrosis probability scores—are mapped to established clinical fibrosis categories (F0–F4). Hybrid AI–clinical models combine algorithmic predictions with clinician input, such as incorporating a radiologist’s elastography inter

Finally, AI systems increasingly incorporate metabolic risk factors—including insulin resistance, lipid profiles, and genetic markers—to provide a holistic assessment of MASLD risk and progression[12].

While AI tools for MASLD show diagnostic promise, real-world adoption depends on overcoming infrastructural and regulatory barriers. EHR-integrated models (e.g., automated FIB-4 calculators) are most feasible, whereas imaging AI requires PACS interoperability and radiologist oversight. Prioritizing use cases with clear region of interest (e.g., fibrosis triage) and investing in clinician-AI collaboration frameworks will accelerate implementation. Prospective trials validating cost-effectiveness (e.g., reduced biopsy rates) are critical for reimbursement and scaling.

Despite advancements and AI promise in MASLD diagnosis, key challenges persist, as technically, data heterogeneity and computational demands limit scalability, while ethical concerns such as algorithmic bias and patient privacy require rigorous governance. Regulatory pathways remain nascent, with few AI tools achieving United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) clearance. Addressing these challenges necessitates collaborative efforts among developers, clinicians, and policymakers to ensure equitable, effective AI implementation. Variability in datasets limits model generalizability[6]. Challenges include ensuring model interpretability (via SHAP) and compliance with regulatory standards for real-world deployment[3]. For validation, most studies are retrospective, so prospective multicenter real-world trials are necessary[7].

The path to AI adoption in MASLD hinges on rigorous validation, regulatory compliance, and seamless clinical integration. Prospective trials to compare AI-driven diagnosis (e.g., CNN-based United States analysis) against liver biopsy in a multicenter cohort must be adopted as a benchmark for AI against gold standards. While regulatory bodies should prioritize transparent, generalizable models.

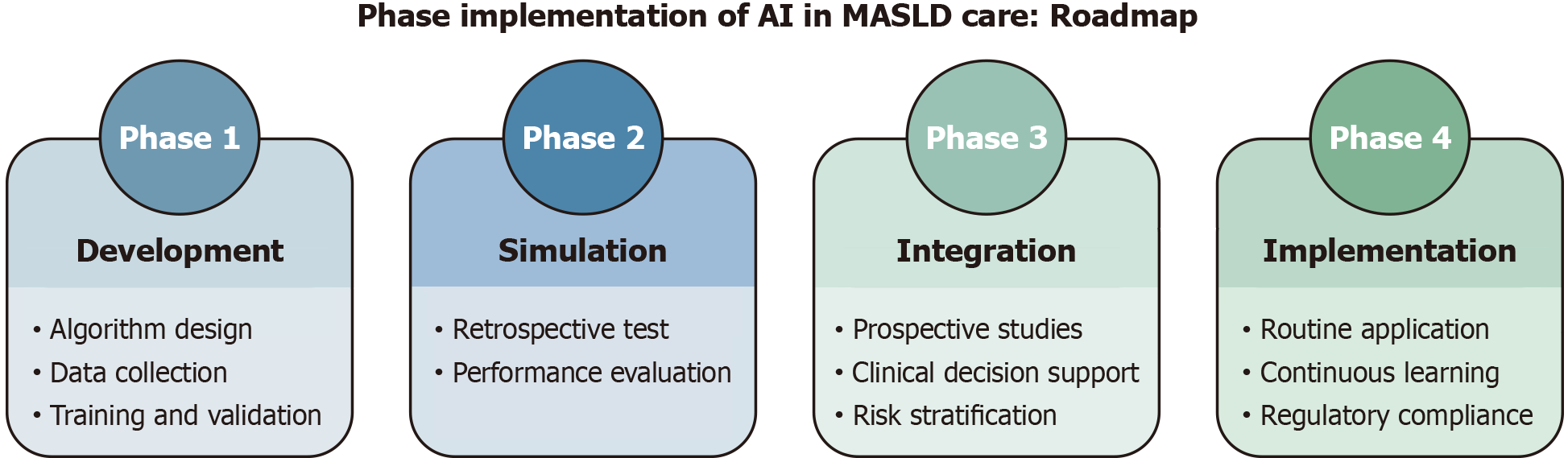

Global harmonization and collaborative efforts—align FDA (United States), European Medicines Agency (European Union), and Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (Japan) guidelines to streamline approvals as by IMDRF’s AI Working Group, and integration into clinical guidelines—through consensus statements to endorse AI tools for specific use cases, as example, first-line steatosis screening in T2DM patients, or flag high-risk patients (e.g., F2 fibrosis) for hepatology referral. Meanwhile, mobile AI solutions can bridge resource gaps, ensuring equitable access. A phased rollout (Figure 1) from pilot studies to global scaling will maximize impact while mitigating risks.

AI holds transformative potential in MASLD diagnosis, offering high accuracy, cost efficiency, and non-invasive alternatives to liver biopsy. ML and DL models excel in risk prediction, imaging analysis, and fibrosis staging, yet require further validation and standardization. Future research should prioritize explain-ability, multicenter collaboration, and integration into clinical workflows to optimize patient outcomes. Continued advancements in AI-driven hepatology will pave the way for more precise and personalized MASLD management. Most studies adopted a hybrid approach, integrating laboratory, imaging, and (when available) histological data to optimize model performance. However, heterogeneity in data sources underscores the need for standardized multimodal datasets in future research.

| 1. | Arab JP, Dirchwolf M, Álvares-da-Silva MR, Barrera F, Benítez C, Castellanos-Fernandez M, Castro-Narro G, Chavez-Tapia N, Chiodi D, Cotrim H, Cusi K, de Oliveira CPMS, Díaz J, Fassio E, Gerona S, Girala M, Hernandez N, Marciano S, Masson W, Méndez-Sánchez N, Leite N, Lozano A, Padilla M, Panduro A, Paraná R, Parise E, Perez M, Poniachik J, Restrepo JC, Ruf A, Silva M, Tagle M, Tapias M, Torres K, Vilar-Gomez E, Costa Gil JE, Gadano A, Arrese M. Latin American Association for the study of the liver (ALEH) practice guidance for the diagnosis and treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Ann Hepatol. 2020;19:674-690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Zhu G, Song Y, Lu Z, Yi Q, Xu R, Xie Y, Geng S, Yang N, Zheng L, Feng X, Zhu R, Wang X, Huang L, Xiang Y. Machine learning models for predicting metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease prevalence using basic demographic and clinical characteristics. J Transl Med. 2025;23:381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yu Y, Yang Y, Li Q, Yuan J, Zha Y. Predicting metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease using explainable machine learning methods. Sci Rep. 2025;15:12382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Canbay A, Kälsch J, Neumann U, Rau M, Hohenester S, Baba HA, Rust C, Geier A, Heider D, Sowa JP. Non-invasive assessment of NAFLD as systemic disease-A machine learning perspective. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0214436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yip TC, Ma AJ, Wong VW, Tse YK, Chan HL, Yuen PC, Wong GL. Laboratory parameter-based machine learning model for excluding non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in the general population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:447-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Ahn JC, Connell A, Simonetto DA, Hughes C, Shah VH. Application of Artificial Intelligence for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2021;73:2546-2563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Spann A, Yasodhara A, Kang J, Watt K, Wang B, Goldenberg A, Bhat M. Applying Machine Learning in Liver Disease and Transplantation: A Comprehensive Review. Hepatology. 2020;71:1093-1105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wakabayashi SI, Kimura T, Tamaki N, Iwadare T, Okumura T, Kobayashi H, Yamashita Y, Tanaka N, Kurosaki M, Umemura T. AI-Based Platelet-Independent Noninvasive Test for Liver Fibrosis in MASLD Patients. JGH Open. 2025;9:e70150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Byra M, Han A, Boehringer AS, Zhang YN, O'Brien WD Jr, Erdman JW Jr, Loomba R, Sirlin CB, Andre M. Liver Fat Assessment in Multiview Sonography Using Transfer Learning With Convolutional Neural Networks. J Ultrasound Med. 2022;41:175-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yasaka K, Akai H, Kunimatsu A, Abe O, Kiryu S. Deep learning for staging liver fibrosis on CT: a pilot study. Eur Radiol. 2018;28:4578-4585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Masaebi F, Azizmohammad Looha M, Mohammadzadeh M, Pahlevani V, Farjam M, Zayeri F, Homayounfar R. Machine-Learning Application for Predicting Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease Using Laboratory and Body Composition Indicators. Arch Iran Med. 2024;27:551-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Perveen S, Shahbaz M, Keshavjee K, Guergachi A. A Systematic Machine Learning Based Approach for the Diagnosis of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Risk and Progression. Sci Rep. 2018;8:2112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/